Abstract

Rivastigmine treatment is associated with significant improvements on the cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog) in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). Both AD and PDD are purported to have different profiles of cognitive impairment, which may respond differentially to rivastigmine treatment. This was a retrospective analysis of 3 randomized, double-blind, rivastigmine trial databases (Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer's disease [IDEAL; AD], EXelon in PaRkinson's disEaSe dementia Study [EXPRESS; PDD], and Alzheimer's Disease with ENA 713 [ADENA; AD]). Factor analyses of the 11 baseline ADAS-cog items derived the same factors in the 2 diseases, that is, “memory” and “language”. Rivastigmine-treated AD and PDD patients showed significant improvements (P < .0001 versus placebo) on both factors. For both AD and PDD, rivastigmine had a numerically greater effect on memory than language. Treatment effect sizes were numerically greater in PDD compared with AD. Rivastigmine treatment is associated with improvement in memory and language in AD and PDD. The numerically greater response in PDD is consistent with greater cholinergic deficits in this disease state.

Keywords: ADAS-cog, factor analysis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease dementia, rivastigmine

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the 2 most common neurodegenerative disorders. Both AD and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) are characterized by cognitive abnormalities, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and significant cholinergic deficits that are even more pronounced in PDD than in AD. 1

A number of controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs), such as rivastigmine, is associated with symptomatic improvements in cognition, behavior, and activities of daily living in patients with mild-to-moderate AD. 2–4 Only rivastigmine has demonstrated such effects in patients with PDD in a large, placebo-controlled clinical trial setting. 5 Based on the results of these trials, rivastigmine is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the symptomatic treatment of mild-to-moderate AD and PDD.

The cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog) was specifically designed to measure the change in cognitive deficits that characterize AD. 6 The ADAS-cog can reliably assess the severity of dementia in patients with AD 7 and is now widely considered the “gold standard” measure of cognitive function in clinical trials of patients with mild-to-moderate AD. Its use has also been validated in PDD. 8 The ADAS-cog assesses global cognitive abilities based on performance on 11 individual items. Patients obtain a total score ranging from 0 to 70, with higher scores indicating more severe cognitive impairment.

A factor analysis of the ADAS-cog using data from a 30-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the ChEI tacrine in people with AD allocated the 11 individual ADAS-cog items to 3 key domains: memory, language, and praxis. 9 However, a subsequent factor analysis in another population of patients with AD receiving rivastigmine allocated the 11 items to only 2 domains. 10 This suggests that the definition of the ADAS-cog “domains” may be influenced by the characteristics of the population under study. Additionally, it is possible that the domains identified on the basis of factor analysis of the ADAS-cog might be different for patients AD and PDD.

The aim of this study was to perform a factor analysis of pooled data from 3 large, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of rivastigmine in patients with AD or PDD. These included a pooled database of data from 4 clinical trials of patients with AD treated with rivastigmine capsules, 3,4,11,12 a large placebo-controlled clinical trial of patients with AD treated with rivastigmine capsules or patches 2 , and a large placebo-controlled trial of PDD patients treated with rivastigmine capsules. 5 Domains of the ADAS-cog were redefined using factor analysis. Efficacy analyses were performed for each domain to compare outcomes in persons with AD to outcomes in people with PDD.

Methods

This was a factor analysis of ADAS-cog items using data from 3 clinical databases (Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer’s disease [IDEAL] trial, CENA713D2320; EXelon in PaRkinson’s disEaSe dementia Study [EXPRESS] trial, CENA713B2311; and the Alzheimer's Disease with ENA 713 [ADENA] database). The full details of the trials included in these databases have been published previously. 2–5,11,12

Briefly, IDEAL was an international, randomized, 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 9.5 mg/24 h rivastigmine patch, 17.4 mg/24 h rivastigmine patch, or 12 mg/d rivastigmine capsules in persons with mild-to-moderately severe AD. 2 EXPRESS was an international, randomized, 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 3 to 12 mg/d rivastigmine capsules in people with probable PD and mild-to-moderately severe dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] 10–24). 5 The ADENA database comprised 4, 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of rivastigmine capsules in patients with probable mild-to-moderate AD (MMSE 10–26). 3,4,11,12 Two studies evaluated rivastigmine 1 to 4 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d; 1 study evaluated rivastigmine 2 to 12 mg/d twice-daily (bid) and thrice-daily (tid); and 1 study evaluated rivastigmine 3, 6, and 9 mg/d. All trials in the ADENA database, IDEAL, and EXPRESS used the total 11-item ADAS-cog score as a primary outcome measure.

For the current study, a new factor analysis using baseline data was performed to establish a “best fit” for the 11 individual ADAS-cog items to possible cognitive domains, and to test whether the domains derived from the ADAS-cog items differed between AD (IDEAL and ADENA) and PDD (EXPRESS) populations. For this new factor analysis, the PROC FACTOR procedure in SAS was used. Initial common factor extraction was performed using the principal component method. Estimates of loadings were obtained using varimax rotation.

Baseline demographics and characteristics were compared between the AD and PDD patient populations. For the randomized population (all treatment groups) P values were derived from a 2 sample t test comparing AD and PDD populations (with the exception of age, where the P values were derived from a chi-square test). Baseline ADAS-cog and MMSE scores between patients with AD and PDD randomized to receive 6 to 12 mg/d rivastigmine capsules were compared using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with study as a factor.

Efficacy analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) and retrieved dropout (RDO) populations using a last observation carried forward (LOCF) imputation (ITT + RDO [LOCF]). The change from baseline at week 24/26 (primary end points in the IDEAL, EXPRESS, and ADENA trials) on the newly defined ADAS-cog domains was calculated. Treatment differences for each domain were assessed by employing 2 ANCOVA models. The first model included treatment as a fixed factor, study as a random factor, and baseline domain score as a covariate applied to data from all treatment groups. The second model included treatment, AD/PDD, treatment by AD/PDD interaction as fixed factors, and baseline domain score as a covariate, applied to only capsule (6 to 12 mg/d) and placebo groups. To compare scores between the 2 newly defined domains, scores were adjusted by the range ([change from baseline in the capsule 6 to 12 mg/d group] × 100/range) or by the range and placebo effect ([change from baseline in the 6 to 12 mg/d capsule group − change from baseline in the placebo group] × 100/range) and the P values were calculated using a paired t test.

Results

Study Population

The baseline demographics and background characteristics of the IDEAL, EXPRESS, and ADENA populations have been reported previously. 2–5,11,12 In total, 4540 patients were randomized (880 patients to 1 to 4 mg/d rivastigmine capsule, 1714 to 6 to 12 mg/d rivastigmine capsule, 293 to 9.5 mg/24 h rivastigmine patch, 303 to 17.4 mg/24 h rivastigmine patch, and 1350 to placebo). The baseline demographics and background characteristics are summarized in Table 1 . In the randomized population, significant differences were observed between patients with AD and PDD in terms of gender and the mean MMSE score at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Background Characteristics of the Randomized Population a (IDEAL, EXPRESS, and ADENA) by Treatment

| Capsule | Patch | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo N = 1350 | 6–12 mg/d | 9.5 mg/24 h | 17.4 mg/24 h | ||

| N = 1714 | N = 293 | N = 303 | |||

| Age, years | |||||

| AD and PDD | |||||

| n | 1350 | 1714 | 293 | 303 | |

| Mean (SD) | 73.3 (7.69) | 72.8 (7.86) | 73.6 (7.85) | 74.2 (7.69) | .1432 |

| AD | |||||

| n | 1171 | 1352 | 293 | 303 | |

| Mean (SD) | 73.4 (7.86) | 72.8 (8.15) | 73.6 (7.85) | 74.2 (7.69) | |

| PDD | |||||

| n | 179 | 362 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 72.4 (6.43) | 72.8 (6.69) | |||

| Female (%) | |||||

| AD and PDD | 57.3 | 56.3 | 67.9 | 66.0 | <.0001 b |

| AD | 60.8 | 61.9 | 67.9 | 66.0 | |

| PDD | 34.6 | 35.4 | – | – | |

| MMSE score | |||||

| AD and PDD | |||||

| n | 1347 | 1711 | 290 | 303 | |

| Mean (SD) | 18.9 (4.36) | 19.0 (4.34) | 16.6 (3.11) | 16.6 (2.94) | .0007 |

| AD | |||||

| n | 1168 | 1349 | 290 | 303 | |

| Mean (SD) | 18.8 (4.40) | 18.9 (4.46) | 16.6 (3.11) | 16.6 (2.94) | |

| PDD | |||||

| n | 179 | 362 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 19.2 (4.08) | 19.4 (3.84) | |||

| Total ADAS-cog score | |||||

| AD and PDD | |||||

| n | 1335 | 1695 | 286 | 301 | |

| Mean (SD) | 24.9 (11.39) | 24.3 (11.40) | 27.0 (10.17) | 27.5 (9.74) | .0562 |

| AD | |||||

| n | 1163 | 1344 | 286 | 301 | |

| Mean (SD) | 25.0 (11.50) | 24.4 (11.69) | 27.0 (10.17) | 27.5 (9.74) | |

| PDD | |||||

| n | 172 | 351 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 23.9 (10.65) | 23.9 (10.25) | |||

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment scale–cognitive subscale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SD, standard deviation; IDEAL, Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer's disease. a Randomized population comprised 4540 patients. However, data for patients randomized to receive rivastigmine 1 to 4 mg/d capsules (n = 880) are not presented. Baseline data were not available for all patients for every category. Patch data are derived from the IDEAL study; therefore, pooled AD/PDD data are the same as for AD data. P values derived from 2-sample t test comparing AD and PDD populations.

b P values derived from chi-square test between AD and PDD populations.

Factor Analysis

To identify factors, the following criteria were used: retained factors had eigenvalues >0.5, domains included items with loading scores >0.4, and items that loaded on multiple factors were included on the factor with the highest loading (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Factor Structure of the New ADAS-cog 2-Factor Analysis for the AD, PDD, and Pooled Patient Populations (Randomized Population a )

| Item | IDEAL and ADENA (AD) | EXPRESS (PDD) | IDEAL, ADENA, and EXPRESS (AD and PDD) a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 3959 | N = 513 | N = 4472 | ||||

| Factor 1 (4.71) b | Factor 2 (0.80) b | Factor 1 (3.90) b | Factor 2 (0.72) b | Factor 1 (4.56) b | Factor 2 (0.79) b | |

| Word recall | 0.67 | 0.23 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.68 | 0.22 |

| Following commands | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.43 |

| Constructional praxis | 0.47 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.18 | 0.45 | 0.21 |

| Naming objects/fingers | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.33 |

| Ideational praxis | 0.57 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.34 |

| Orientation | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.62 | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.16 |

| Word recognition | 0.65 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 0.12 | 0.64 | 0.16 |

| Remembering test instructions | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.42 |

| Spoken language ability | 0.22 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0.79 |

| Word-finding difficulty | 0.27 | 0.77 | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.27 | 0.76 |

| Comprehension of spoken language | 0.32 | 0.73 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.32 | 0.73 |

Abbreviations: IDEAL, Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer’s disease; EXPRESS, EXelon in PaRkinson’s disEaSe dementia Study; ADENA, Alzheimer's Disease with ENA 713; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia.

aOf the randomized population (n = 4540), baseline ADAS-cog data were provided by 4472 patients.

bEigenvalues. Two domains were derived from a factor analysis on the covariance matrix of 11 baseline ADAS-cog items using a varimax rotation. Factors retained had eigenvalues >0.5. Domains took the sum of each item that loaded >0.4; items that loaded on multiple factors were included in the factor with the highest loading.

Items that loaded most highly on the factor are shown in bold.

ADAS-cog data for all 11 baseline items were available for 4472 patients in the randomized population (3959 patients with AD [IDEAL and ADENA] and 513 patients with PDD [EXPRESS]). Factor analyses of 11 baseline ADAS-cog items led to the same 2 domains in both AD and PDD (Table 2). The first factor included 8 items: word recall, following commands, constructional praxis, naming objects/fingers, ideational praxis, orientation, word recognition, and remembering test instructions. The second domain consisted of 3 items: spoken language ability, word-finding difficulty, and comprehension of spoken language. Based on the individual items that comprised each factor, we termed the first domain “memory” and the second one “language.”

Efficacy Outcomes Using the New ADAS-cog 2-Factor Analysis

The change from baseline at week 24/26 in the ITT + RDO (LOCF) AD, PDD, and pooled populations on the 2 new ADAS-cog domains (memory and language) are shown in Tables 3 and 4 .

Table 3.

Mean Change From Baseline at Week 24/26 on the New ADAS-cog Language and Memory Domains for AD and PDD Patients (Pooled Population) Receiving Rivastigmine Capsules, Rivastigmine Patch, or Placebo (IDEAL, EXPRESS, and ADENA; ITT + RDO [LOCF]) Population) a

| Memory Domain | Language Domain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Capsule | Patch | Placebo | Capsule | Patch | |||

| N = 1300 | 6–12 mg/d; N = 1640 | 9.5 mg/24 h; N = 260 | 17.4 mg/24 h; N = 272 | N = 1316 | 6–12 mg/d; N = 1662 | 9.5 mg/24 h; N = 266 | 17.4 mg/24 h; N = 279 | |

| Pooled population | ||||||||

| Baseline mean (SD) | 22.3 (9.56) | 21.7 (9.49) | 24.4 (8.63) | 24.7 (7.88) | 2.5 (2.96) | 2.5 (2.88) | 2.7 (2.94) | 2.6 (2.85) |

| LS Mean change at week 24/26 (SE) | 1.52 (0.41) | −0.34 (0.41) | −0.03 (0.54) | −0.81 (0.53) | 0.49 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.06) | −0.11 (0.14) | −0.28 (0.13) |

| Effect size | – | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.53 | – | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| P value versus placebo | – | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | – | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; LS, least squares; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; ITT + RDO [LOCF], intention-to-treat (ITT) and retrieved dropout (RDO) populations using a last observation carried forward (LOCF) imputation; IDEAL, Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer’s disease; EXPRESS, EXelon in PaRkinson’s disEaSe dementia Study; ADENA, Alzheimer's Disease with ENA 713.

a ITT + RDO [LOCF] population was comprised of 4405 patients. However, data for patients randomized to receive rivastigmine 1 to 4 mg/d capsules are not presented and data were not available for all patients because of missing values. Data are from analysis of covariance model with treatment as a fixed factor, study as a random factor, and baseline ADAS-cog domain score as a covariate. Effect size was calculated from mean values. Memory domain includes items: word recall, following commands, constructional praxis, naming objects/fingers, ideational praxis, orientation, word recognition, and remembering test instructions. Language domain includes items: spoken language ability, word-finding difficulty, and comprehension of spoken language.

Table 4.

Mean Change From Baseline at Week 24/26 on the New ADAS-Cog Language and Memory Domains for Patients Receiving Rivastigmine Capsules or Placebo in the AD, PDD, or Pooled Populations (IDEAL, EXPRESS, and ADENA; ITT + RDO [LOCF] Population) a

| Memory Domain | Language Domain | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Capsule,6–12 mg/d | Placebo | Capsule, 6–12 mg/d | |

| Pooled population | ||||

| N | 1300 | 1640 | 1316 | 1662 |

| Baseline mean (SD) | 22.3 (9.56) | 21.7 (9.49) | 2.5 (2.96) | 2.5 (2.88) |

| LS mean change at week 24/26 (SE) | 0.96 (0.22) | −1.06 (0.16) | 0.47 (0.09) | −0.03 (0.06) |

| Effect size | – | 0.36 | – | 0.21 |

| P value versus placebo | – | <.0001 | – | <.0001 |

| AD | ||||

| N | 1146 | 1323 | 1152 | 1328 |

| Baseline mean (SD) | 22.5 (9.65) | 22.0 (9.79) | 2.4 (2.94) | 2.4 (2.82) |

| LS mean change at week 24/26 (SE) | 1.77 (0.15) | 0.07 (0.14) | 0.50 (0.06) | 0.09 (0.06) |

| Effect size | – | 0.33 | – | 0.20 |

| P value versus placebo | – | <.0001 | – | <.0001 |

| PDD | ||||

| N | 154 | 317 | 164 | 334 |

| Baseline mean (SD) | 21.2 (8.77) | 20.7 (8.04) | 3.1 (3.01) | 2.9 (3.04) |

| LS mean change at week 24/26 (SE) | 0.14 (0.42) | −2.20 (0.29) | 0.44 (0.17) | −0.15 (0.12) |

| Effect size | – | 0.37 | – | 0.22 |

| P value versus placebo | – | <.0001 | – | <.0033 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale; LS, least squares; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; ITT + RDO [LOCF], intention-to-treat (ITT) and retrieved dropout (RDO) populations using a last observation carried forward (LOCF) imputation; IDEAL, Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer’s disease; EXPRESS, EXelon in PaRkinson’s disEaSe dementia Study; ADENA, Alzheimer's Disease with ENA 713.

a ITT + RDO [LOCF] population was comprised of 4405 patients. However, data for patients randomized to receive rivastigmine 1 to 4 mg/d capsules are not presented and data were not available for all patients because of missing values. Data are from an analysis of covariance model with treatment, AD/PDD, and treatment by AD/PDD as factors, and baseline ADAS-cog domain score as a covariate applied to data from capsule 6 to 12 mg/d and placebo groups. Effect size calculated from mean values. Memory domain includes items: word recall, following commands, constructional praxis, naming objects/fingers, ideational praxis, orientation, word recognition, and remembering test instructions. Language domain includes items: spoken language ability, word-finding difficulty, and comprehension of spoken language.

In the pooled population (Table 3), rivastigmine-treated patients showed significant improvements in both the ADAS-cog memory and language domains, as assessed by the least squares (LS) mean change from baseline at week 24/26 (all Ps <.0001 versus placebo). In all treatment groups, the effect size tended to be greater on the memory domain than the language domain and was greatest for the 17.4 mg/24 h patch (memory 0.53; language 0.37), followed by the 9.5 mg/24 h patch (memory 0.38; language 0.30), and rivastigmine 6 to 12 mg/d capsule (memory 0.36; language 0.21). Comparing adjusted scores on the memory and language domains for the rivastigmine 6 to 12 mg/d capsule group showed significant differences between the domain scores in the total population (P = .0070) and the PDD population (P = .0038) but not the AD population (P = .1345). However, no significant differences (P > .05) were seen between the adjusted scores on the memory and language domains in any patient population when taking into account the placebo effects.

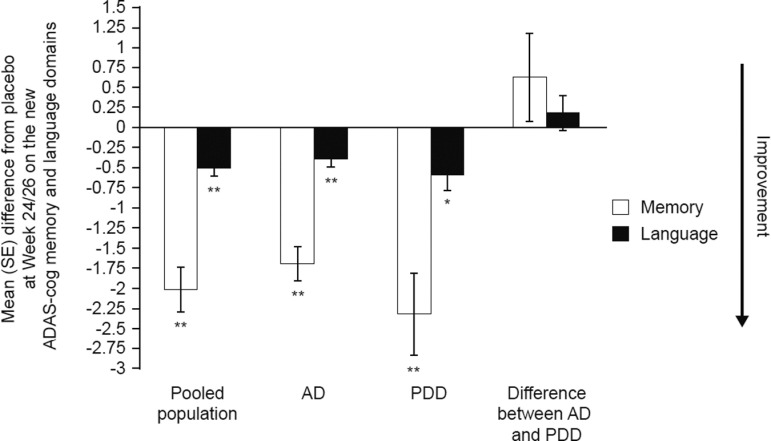

To investigate treatment differences in patients with AD compared with PDD using the new ADAS-cog domains, rivastigmine 6 to 12 mg/d capsules were used because they were included as a treatment arm in IDEAL, ADENA, and EXPESS. This is in contrast to the rivastigmine patch, which was not investigated in ADENA or EXPRESS. Baseline total ADAS-cog (P = .3291) and MMSE (P = .0636) scores were not significantly different between patients with AD or PDD randomized to receive 6 to 12 mg/d rivastigmine capsules, suggesting that the severity of dementia was similar in the 2 patient populations. Significant changes from baseline at week 24/26 were seen on the memory and language domains for patients randomized to receive 6 to 12 mg/d rivastigmine capsules for the pooled (memory P < .0001 and language P < .0001), AD (memory P < .0001 and language P < .0001), and PDD (memory P < .0001 and language P = .0033) populations (Table 4). On both the memory and language domains, the treatment effect was numerically greater, but not statistically different, in patients with PDD compared with AD patients, as assessed by the LS mean difference from placebo (Figure 1 ; P = .4010, language domain and P = .2543, memory domain) and by effect sizes (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Mean difference from placebo at week 24/26 on ADAS-cog memory and language domains for rivastigmine capsules (6-12 mg/d) versus placebo in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and/or PDD patients ([IDEAL], [EXPRESS] and [ADENA] intention-to-treat [ITT] + retrieved dropout [RDO]; last observation carried forward [LOCF] population). Analysis of covariance model with treatment, AD/PDD, and treatment by AD/PDD as fixed factors and baseline ADAS-cog domain score as a covariate. P values for pairwise comparison versus placebo or for AD versus PDD adjusted by placebo: *P ≤ .01; **P ≤ .0001. Error bars represent the standard error (SE) of the mean. Memory domain includes the following items: word recall, following commands, constructional praxis, naming objects/fingers, ideational praxis, orientation, word recognition, and remembering test instructions. Language domain includes the following items: spoken language ability, word-finding difficulty, and comprehension of spoken language. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; IDEAL, Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer’s disease; EXPRESS, EXelon in PaRkinson's disEaSe dementia Study; ADENA, Alzheimer’s Disease with ENA 713 database.

Discussion

In the current study, a new 2-factor analysis of the ADAS-cog was generated using pooled data from 3 large, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial databases that enrolled over 4000 patients with AD or PDD. Patients with AD and PDD were found to have similar item scores in the factor analysis; hence, the new ADAS-cog factor analysis was developed using pooled data from AD and PDD patients. Improvements on both the newly defined ADAS-cog memory and language domains were demonstrated in patients with AD or PDD that were treated with rivastigmine. Treatment effect sizes were numerically greater for memory than for language and also for PDD patients compared with AD patients, particularly on the memory domain.

Although both AD and PDD are characterized by cognitive abnormalities, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and cholinergic deficits, there are distinctions between the 2 disorders in terms of cognitive profiles, including differential effects on memory, executive function, language, and attention. Review of data from large, placebo-controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that patients with AD showed more rapid cognitive decline than those with PDD. 1 In patients with AD, the cognitive abilities were stabilized by rivastigmine compared with decline in placebo groups, whereas symptomatic improvements above baseline may be associated with treatment effects in patients with PDD. Additionally, cholinergically mediated adverse events such as nausea and vomiting may be less frequent in PDD than AD. 1 It remains to be established whether these clinical distinctions are related to the apparently increased efficacy of rivastigmine in patients with PDD compared with those with AD, as detected using the new 2-factor ADAS-cog in the current study, or whether the newly selected ADAS-cog factors are more aligned to assessment of treatment response in PDD.

The new 2-factor analysis appears robust as it is consistent with the previous studies that have demonstrated improvements with rivastigmine capsules and patch on the ADAS-cog individual items and its traditional subscales. 2–5,11,12 Using the 3 domains derived from the tacrine study, 9 Farlow et al 13 demonstrated statistically significant benefits with 6 to 12 mg/d rivastigmine capsules versus placebo on all 3 ADAS-cog domains and several individual items in patients with AD. 13 In addition, Schmitt et al 14 demonstrated statistically significant benefits with 3 to 12 mg/d rivastigmine capsules versus placebo on all 3 ADAS-cog domains and several individual items in patients with PDD. 14 Largest treatment effects in patients with PDD were seen on the word recall, ideational praxis, and comprehension items. 14

The recent study by Grossberg et al 10 was the first to report ADAS-cog individual item scores with the rivastigmine patch in patients with mild-to-moderate AD (IDEAL study). 2 In that study, a new factor analysis in patients with AD allocated the 11 ADAS-cog items to 2 domains. The new “direct cognitive assessments” domain comprised all items previously allocated to the memory and praxis domains, except recall of test instructions, which was replaced by following commands. The new “subjective rater assessments” domain comprised all items previously allocated to the language domain, except following commands, which was replaced by recall of test instructions. All rivastigmine-treated groups demonstrated significant improvement in direct cognitive assessments. 10 In the current study, the large population, mixed study population, and range of treatment modalities and doses have provided a more comprehensive database on which to perform a factor analysis of the ADAS-cog that appears to be robust across different common neurodegenerative diseases.

The current analysis is limited by its retrospective nature. Individual studies were not powered to detect significant differences on individual ADAS-cog item scores or domains, and data were not corrected for multiple comparisons due to the exploratory nature of the analyses. Nonetheless, the analyses in the current study have value in hypothesis generation.

In conclusion, a new 2-factor analysis of the ADAS-cog has been developed using data from over 4000 patients with AD or PDD. Using this updated factor analysis, improvements in the newly defined ADAS-cog memory and language domains were demonstrated in patients with AD and PDD that were treated with rivastigmine. The new 2-factor ADAS-cog is sensitive to disease-specific improvements in memory and language across common neurological disorders.

Acknowledgments

Novartis develop and manufacture rivastigmine, and sponsored the large, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trials that led to the approval of rivastigmine in the United States for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). The current data analyses were supported by Novartis. Alpha-Plus Medical Communications Ltd (UK) provided medical writing and editorial support in the production of this manuscript; this service was sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, New Jersey, USA.

Footnotes

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: DW has received grants/research funding from the National Institute of Health and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research; honoraria for consulting and advisory board membership from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Labopharm Pharmaceuticals and Denysias Bioscience; and licensing fees for Intellectual Property Rights from the University of Pennsylvania; and honoraria from the Movement Disorder Society, Elsevier, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. MS and XM are full-time employees and stockholders of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, New Jersey.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Emre M, Cummings JL, Lane RM. Rivastigmine in dementia associated with Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease: similarities and differences. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11(4):509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Winblad B, Cummings J, Andreasen N, et al. A six-month double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of a transdermal patch in Alzheimer's disease–rivastigmine patch versus capsule. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(5):456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rösler M, Anand R, Cicin-Sain A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer's disease: international randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999;318(7184):633–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corey-Bloom J, Anand R, Veach J. A randomized trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of ENA 713 (rivastigmine tartrate), a new acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, in patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychopharmacol. 1998;1(2):55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Emre M, Aarsland D, Albanese A, et al. Rivastigmine for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(24):2509–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(11):1356–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weyer G, Erzigkeit H, Kanowski S, Ihl R, Hadler D. Alzheimer's disease assessment scale: reliability and validity in a multicenter clinical trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(2):123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harvey PD, Ferris SH, Cummings JL, et al. Evaluation of dementia rating scales in Parkinson’s disease dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(2):142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olin J, Schneider L. Assessing response to tacrine using the factor analytic structure of the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS)-cognitive subscale. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10(9):753–756. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grossberg GT, Schmitt FA, Meng X, Tekin S, Olin JT. Effects of transdermal rivastigmine on ADAS-cog items in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(8):627–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schneider LS, Anand R, Farlow MR. Systematic review of the efficacy of rivastigmine for patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychopharmacol. 1998;1(suppl 1):S26–S34. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feldman HH, Lane R. Rivastigmine: A placebo-controlled trial of BID and TID regimens in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(10):1056–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Farlow MR, Cummings JL, Olin JT, Meng X. Effects of oral rivastigmine on cognitive domains in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(4):347–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schmitt FA, Aarsland D, Bronnick KS, Meng X, Tekin S, Olin JT. Evaluating rivastigmine in mild-to-moderate Parkinson's disease dementia using ADAS-cog items. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(5):407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]