Abstract

We aimed to study how patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) suffer from awareness of their deficits. Self-awareness was assessed using the Anosognosia Questionnaire for Dementia in 12 pairs of MCI outpatients and caregivers, 23 with mild AD, and 18 with moderate AD. The discrepancy between patient’s and caregiver’s evaluation (anosognosia) became greater as AD progressed. The predictors of patients’ distress, shown by multiple linear regression analyses, were awareness of decline in intellectual or social functioning; self-awareness of deficits in remembering appointments in MCI; in remembering appointments, writing, mental calculation, and understanding the newspaper in mild AD; and in mental calculation and doing clerical work in moderate AD. Caregivers assumed the predictors of patients’ distress differently: awareness of deterioration of memory in MCI and mild AD, and basic activities of daily living in moderate AD. Understanding patients’ disability from patients’ perspective is required for successful care.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, anosognosia, self-monitoring, self-awareness, empathy

Introduction

Deficits in self-awareness of disease, anosognosia, has been recognized as one of the typical symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). 1 The unawareness of impairment is manifested in several domains, including memory and other cognitive functions, and psychological and behavioral functions. 2 –4 As for neural substrates of self-awareness, previous research has identified involvement of posterior dorsomedial regions of the parietal lobe including the precuneus and the temporoparietal junction, as well as the prefrontal cortex, in experiments with healthy volunteers. 5 –7 The experiments in patients with AD showed that those areas are related to deficits in self-awareness 8 –10 and decline of regional cerebral blood flow is observed from the early stages of disease. 11 –13 The finding is consistent with the symptomatic changes occurring as neurodegeneration progresses; self-awareness gradually deteriorates as the disease progresses. 4,14

These neuropsychological findings are beneficial if they are implemented to care for patients with AD. Previous studies reported that behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) could be caused by deficits of self-awareness. 15 –17 From the caregivers’ perspective, BPSD increases caregiver distress. 18 However, it is essential to understand the perspective of patients for treatment and care of BPSD. 19,20 To our knowledge, few studies have tried to elucidate the awareness of the deficits from the patients’ perspective. For a better understanding of patients’ perspective, we assessed the self-awareness of patients and analyzed their distress caused by self-awareness of their deficits. To understand the discrepancy, we also assessed caregivers’ perspectives of patients’ abilities and how the caregivers assessed patients’ distress. We hypothesized that patients retain self-awareness of deficits partially and/or insufficiently and feel distressed by self-awareness at least in the early stage of AD, which the caregivers’ might assess differently. The BPSD could result from such misunderstanding of how patients feel, rather than objective assessment of function. It would contribute to beneficial care of patients with AD to understand patients’ distress related to self-awareness of deficits.

Methods

The participants were 53 pairs of outpatients and their caregivers: 12 amnesic patients with Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) 0.5, 23 with mild AD (CDR 1), and 18 with moderate AD (CDR 2). Demographic data are shown in Table 1. The exclusion criteria were psychiatric diseases, delirium, and verbal incomprehension including aphasia. Participants were diagnosed based on the criteria for AD by National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA), 21 and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) by the report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. 22 The CDR 0.5 was regarded as MCI, although a different classification was proposed whereby CDR 0.5 encompasses both mild and earlier dementia 23 or it corresponds to very mild dementia. 24 Patients with CDR 0.5 were limited to those free from objective symptoms of other types of dementia such as dementia with Lewy bodies or frontotemporal dementia. Patients with scores over 7 on the Japanese version of the Short Form of the Geriatric Depression Scale, 25 which has a full score of 15, were also excluded because depressive tendency could affect self-evaluation. 26 ,27 The ethics board of the Gunma University School of Health Sciences approved all procedures (No. 21-27), and written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Table 1.

Demographic Data a

| CDR | n | Gender, n (M, F) | Mean ± SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | Education, years | MMSE | |||

| 0.5 | 12 | (2, 10) | 74.8 ± 5.0 | 10.5 ± 2.3 | 26.9 ± 1.5 |

| 1 | 23 | (9, 14) | 79.6 ± 7.8 | 9.4 ± 2.1 | 19.9 ± 4.1 |

| 2 | 18 | (3, 15) | 82.3 ± 17.8 | 9.4 ± 3.5 | 12.5 ± 5.7 |

Abbreviations: CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating scale; M, male; F, female; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SD, standard deviation.

a There were no significant differences among groups in age (P = .193), gender (P = .185, chi-square test), or education (P = .535). Scores on MMSE were significantly different among groups (P < .001).

Anosognosia was evaluated by the questionnaire discrepancy method, which compares patient’s self-report with that of a caregiver. 28 The patients and caregivers were required to answer the same questions about the function of the patients independently. The caregivers’ assessment was considered as the objective standard and discrepancy was analyzed between the patients’ and the caregivers’ assessment.

We chose the Japanese version of the Anosognosia Questionnaire for Dementia (AQ-D), 3 ,29,30 which contains questions asking awareness of deficits on intellectual functioning (22 items), and mood and behavior domains (8 items). Each item of the AQ-D was evaluated on 0 to 3 scales: never (0 point), sometimes (1 point), usually (2 points), or always (3 points). Lower scores of the patients meant deficits of awareness in comparison with those of the caregivers. Self-awareness for each item was analyzed by one-sample t test. Summed scores of the 2 domains were compared among CDR groups using 1 × 3 analysis of variance ([ANOVA]; 3 groups according to CDR). The caregivers’ scores were analyzed in the same fashion. Discrepancy of each item was evaluated by paired t test. Scores of the 2 domains were summed up, and those summed scores were compared among CDR groups using 2 × 3 repeated measured ANOVA (the patients and their caregivers in pairs and 3 groups according to CDR).

To understand patients’ perspective, how patients feel distressed by self-awareness of deficits was analyzed as below. The patients’ scores of mood and behavior domain were regarded as their distress from the patients’ perspective. 31 The predictors of scores of mood and behavior domain were analyzed using multiple linear regression analyses. The dependent variables were summed scores of mood and behavior domains (8 items), and the candidates of predictors were chosen among items in intellectual functioning domain. All the 22 items in intellectual functioning domain were assessed by one sample t test, and those items with statistical significance (P < .05) were entered in a stepwise fashion into multiple linear regression analyses. The caregivers’ assessment was analyzed in the same fashion to show how the caregivers assessed the patients’ distress.

The patients were also tested using the Mini-Mental State Examination. All analyses were conducted using the Japanese version of SPSS for Windows version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, New York). Significance was set as P < .05.

Results

Self-awareness of the Patients

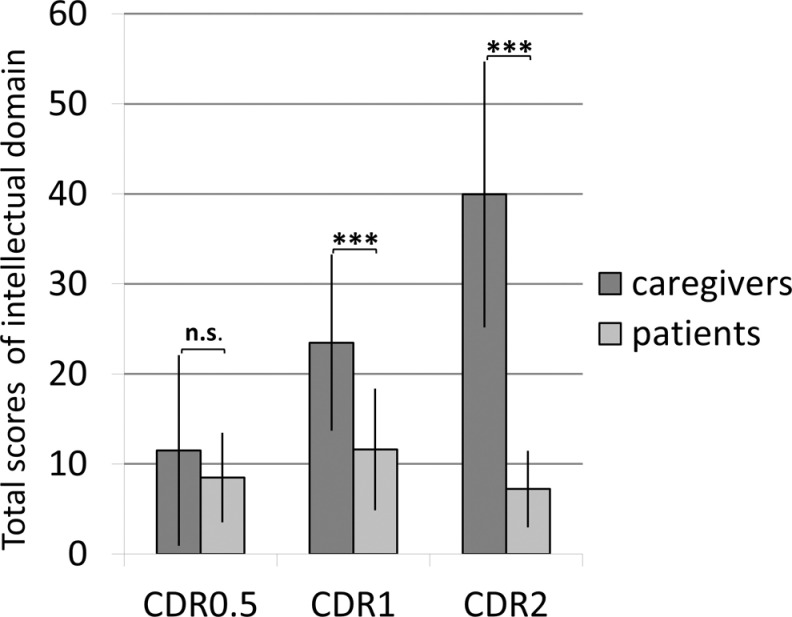

In intellectual functioning domain, patients’ assessments were 8.5 ± 4.9 in CDR 0.5, 11.6 ± 6.7 in CDR 1, and 7.2 ± 4.1 in CDR 2 (Table 2). There was a significant difference among the groups (P = .042); however, self-evaluation of patients in CDR 2 was not significantly different from that of patients in CDR 0.5 (Figure 1).

Table 2.

The Results of Each Item

| Caregivers a | Patients b | Disc c | Pred. C d | Pred. P e | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | P value | ||||

| Intellectual functioning domain | |||||||

| 1 | Problems with remembering dates | 0.5 | 1.17 ± 0.83 g | 0.92 ± 0.67 g | .429 | ||

| 1 | 1.91 ± 0.79 h | 1.30 ± 0.76 h | .016 f | ||||

| 2 | 2.61 ± 0.50 h | 1.11 ± 0.76 h | <.001 h | ||||

| 2 | Problems with orientation in new places | 0.5 | 0.42 ± 0.51 f | 0.25 ± 0.45 | .166 | ||

| 1 | 1.17 ± 1.03 h | 0.74 ± 0.92 g | .047 f | ||||

| 2 | 1.78 ± 1.00 h | 0.78 ± 0.73 h | .004 g | ||||

| 3 | Problems with remembering telephone call | 0.5 | 0.50 ± 0.67 f | 0.33 ± 0.49 f | .551 | ||

| 1 | 1.43 ± 0.79 h | 0.65 ± 0.71 h | <.001 h | ||||

| 2 | 2.06 ± 1.11 h | 0.17 ± 0.38 | <.001 h | ||||

| 4 | Problems with understanding conversations | 0.5 | 0.58 ± 0.67 f | 0.33 ± 0.49 f | .389 | ||

| 1 | 1.13 ± .63 h | 0.52 ± 0.59 h | .002 g | ||||

| 2 | 1.78 ± 0.88 h | 0.11 ± 0.47 | <.001 h | ||||

| 5 | Problems with signing your name | 0.5 | 0.08 ± 0.29 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | .339 | ||

| 1 | 0.22 ± 0.42 f | 0.17 ± 0.49 | .747 | ||||

| 2 | 1.33 ± 1.14 h | 0.00 ± 0.00 | <.001 h | ||||

| 6 | Problems with understanding the newspaper | 0.5 | 0.25 ± 0.45 | 0.58 ± 0.67 f | .166 | ||

| 1 | 1.00 ± 0.95 h | 0.43 ± 0.51 h | .020 f | .221 f | |||

| 2 | 1.94 ± 0.94 h | 0.11 ± 0.32 | <.001 h | ||||

| 7 | Problems with keeping belongings in order | 0.5 | 0.75 ± 0.97 f | 0.58 ± 0.79 f | .551 | ||

| 1 | 1.61 ± 0.99 h | 0.43 ± 0.66 g | <.001 h | ||||

| 2 | 2.44 ± 0.70 h | 0.22 ± 0.43 f | <.001 h | ||||

| 8 | Problems with remembering where things were left | 0.5 | 1.50 ± 0.80 h | 0.83 ± 0.39 h | .005 g | .555 f | |

| 1 | 1.78 ± 0.80 h | 1.04 ± 0.64 h | .001 g | .352 g | |||

| 2 | 2.33 ± 0.77 h | 0.83 ± 0.51 h | <.001 h | ||||

| 9 | Problems with writing | 0.5 | 0.67 ± 0.89 f | 0.33 ± 0.49 f | .166 | ||

| 1 | 0.96 ± 0.71 h | 0.52 ± 0.79 g | .022 f | .934 h | .533 h | ||

| 2 | 2.17 ± 0.86 h | 0.28 ± 0.75 | <.001 h | ||||

| 10 | Problems with handling money | 0.5 | 0.50 ± 1.00 | 0.25 ± 0.62 | .082 | ||

| 1 | 1.04 ± 1.07 h | 0.35 ± 0.71 f | .015 f | ||||

| 2 | 2.06 ± 1.00 h | 0.11 ± 0.47 | <.001 h | ||||

| 11 | Problems with orientation in your neighborhood | 0.5 | 0.33 ± 0.89 | 0.08 ± 0.29 | .389 | ||

| 1 | 0.65 ± 0.83 g | 0.30 ± 0.56 f | .103 | ||||

| 2 | 1.39 ± 1.14 h | 0.11 ± 0.32 | <.001 h | ||||

| 12 | Problems with remembering appointments | 0.5 | 0.67 ± 0.89 f | 0.50 ± 0.52 g | .504 | .766 g | |

| 1 | 1.78 ± 0.95 h | 0.78 ± 0.67 h | <.001 h | .388 g | |||

| 2 | 1.94 ± 0.80 h | 0.56 ± 0.62 g | <.001 h | ||||

| 13 | Problems with practicing favorite hobbies | 0.5 | 0.17 ± 0.39 | 0.25 ± 0.45 | .674 | ||

| 1 | 0.83 ± 0.94 h | 0.39 ± 0.72 f | .038 f | −.309 f | |||

| 2 | 1.67 ± 0.97 h | 0.28 ± 0.75 | <.001 h | ||||

| 14 | Problems with communicating with people | 0.5 | 0.08 ± 0.29 | 0.25 ± 0.45 | .339 | ||

| 1 | 0.74 ± 0.69 h | 0.35 ± 0.49 g | .025 f | ||||

| 2 | 1.39 ± 0.92 h | 0.00 ± 0.00 | <.001 h | −.471 h | |||

| 15 | Problems with mental calculations | 0.5 | 0.42 ± 0.67 | 0.83 ± 0.39 h | .054 | ||

| 1 | 1.17 ± 0.89 h | 1.22 ± 0.80 h | .852 | .322 g | |||

| 2 | 1.83 ± 1.10 h | 0.83 ± 1.15 g | .022 f | .523 g | |||

| 16 | Problems with remembering shopping lists | 0.5 | 0.75 ± 0.87 f | 0.58 ± 0.51 g | .638 | ||

| 1 | 1.65 ± 0.93 h | 0.74 ± 0.81 h | <.001 h | ||||

| 2 | 2.22 ± 0.81 h | 0.50 ± 0.71 g | <.001 h | ||||

| 17 | Problems with bladder control | 0.5 | 0.17 ± 0.58 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | .339 | ||

| 1 | 0.39 ± 0.84 f | 0.13 ± 0.34 | .186 | ||||

| 2 | 1.00 ± 1.03 g | 0.00 ± 0.00 | .001 g | .382 g | |||

| 18 | Problems with understanding the plot of a movie | 0.5 | 0.25 ± 0.45 | 0.42 ± 0.51 f | .438 | ||

| 1 | 1.09 ± 0.67 h | 0.52 ± 0.51 h | .006 g | ||||

| 2 | 1.67 ± 1.03 h | 0.11 ± 0.32 | <.001 h | ||||

| 19 | Problems with orientation in the house | 0.5 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | – | ||

| 1 | 0.13 ± 0.34 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | .083 | ||||

| 2 | 0.94 ± 1.11 g | 0.00 ± 0.00 | .002 g | ||||

| 20 | Problems with doing home activities | 0.5 | 0.92 ± 1.16 f | 0.42 ± 0.67 | .166 | ||

| 1 | 1.09 ± 1.04 h | 0.22 ± 0.42 f | .001 g | ||||

| 2 | 2.06 ± 0.94 h | 0.11 ± 0.32 | <.001 h | ||||

| 21 | Problems with feeding oneself | 0.5 | 0.42 ± 1.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | .175 | ||

| 1 | 0.17 ± 0.49 | 0.04 ± 0.21 | .266 | ||||

| 2 | 1.00 ± 1.14 g | 0.06 ± 0.24 | .004 g | .490 h | |||

| 22 | Problems with doing clerical work | 0.5 | 0.92 ± 1.16 f | 0.75 ± 0.97 f | .504 | .439 f | |

| 1 | 1.52 ± 1.08 h | 0.74 ± 1.10 g | .002 g | ||||

| 2 | 2.33 ± 0.84 h | 0.94 ± 1.35 g | .002 g | .574 h | .439 f | ||

| Sum | 0.5 | 11.50 ± 10.48 h | 8.50 ± 4.87 h | 0.389 | |||

| 1 | 23.48 ± 9.68 h | 11.61 ± 6.66 h | <.001 h | ||||

| 2 | 39.94 ± 14.65 h | 7.22 ± 4.14 h | <.001 h | ||||

| Mood and behavior domains | |||||||

| 23 | More rigid and inflexible about decisions | 0.5 | 0.75 ± 0.87 f | 0.58 ± 0.90 f | .339 | ||

| 1 | 1.57 ± 0.90 h | 0.61 ± 0.72 g | <.001 h | ||||

| 2 | 2.06 ± 0.80 h | 0.94 ± 1.21 g | .003 g | ||||

| 24 | More egotistical and self-centered | 0.5 | 0.92 ± 0.90 g | 0.58 ± 0.67 f | .266 | ||

| 1 | 1.39 ± 0.94 h | 0.26 ± 0.45 f | <.001 h | ||||

| 2 | 1.56 ± 0.86 h | 0.67 ± 0.97 f | <.001 h | ||||

| 25 | More irritable | 0.5 | 0.50 ± 0.67 f | 0.58 ± 0.51 g | .723 | ||

| 1 | 0.96 ± 0.93 h | 0.39 ± 0.58 g | .020 f | ||||

| 2 | 1.22 ± 0.88 h | 0.83 ± 1.04 g | .149 | ||||

| 26 | More frequent crying episodes | 0.5 | 0.08 ± 0.29 | 0.42 ± 0.51 f | .104 | ||

| 1 | 0.48 ± 0.79 g | 0.43 ± 0.66 g | .770 | ||||

| 2 | 0.67 ± 0.84 g | 0.83 ± 0.99 g | .636 | ||||

| 27 | Laughing inappropriately | 0.5 | 0.08 ± 0.29 | 0.17 ± 0.39 | .586 | ||

| 1 | 0.17 ± 0.39 f | 0.22 ± 0.52 | .770 | ||||

| 2 | 0.39 ± 0.61 f | 0.06 ± 0.24 | .029 f | ||||

| 28 | Increased sexual interest | 0.5 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.17 ± 0.39 | .166 | ||

| 1 | 0.13 ± 0.34 | 0.09 ± 0.29 | .665 | ||||

| 2 | 0.11 ± 0.32 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | .579 | ||||

| 29 | Less interest in favorite activities | 0.5 | 0.50 ± 0.67 f | .42 ± 0.51 f | .723 | ||

| 1 | 1.00 ± 0.85 h | .65 ± 0.93 g | .088 | ||||

| 2 | 1.61 ± .92 h | .61 ± 1.04 f | .001 g | ||||

| 30 | More depressed | 0.5 | .83 ± 0.83 g | .42 ± 0.67 | .096 | ||

| 1 | 1.13 ± 0.87 h | 0.70 ± 0.76 h | .038 f | ||||

| 2 | 1.33 ± 0.69 h | .56 ± 0.92 f | .012 f | ||||

| Sum | 0.5 | 3.67 ± 2.77 h | 3.33 ± 2.99 h | 0.768 | |||

| 1 | 6.83 ± 3.41 h | 3.35 ± 2.92 h | <.001 h | ||||

| 2 | 8.94 ± 2.60 h | 4.56 ± 4.00 h | <.001 h | ||||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating scale.

a Scores of caregivers were analyzed by one-sample t test, and statistically significance was denoted.

b Scores of caregivers patients were analyzed by one-sample t test, and statistically significance was denoted.

c Discrepancy between caregivers’ and patients’ assessment, showing severity of anosognosia; discrepancy was evaluated by paired t test.

d Predictors of distress in caregivers were analyzed by multivariate regression model, and statistically significant standardized beta value was shown in the column.

e Predictors of distress in patients were analyzed by multivariate regression model, and statistically significant standardized beta value was shown in the column.

f P < .05.

g P < .01.

h P < .001.

Figure 1.

Discrepancy between patients’ and caregivers assessment in intellectual functioning domain. Discrepancy was evident in CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) 1 and 2 groups (P < .001 in both), but not in CDR 0.5 group (P = .389). Caregivers assessment was aggravated as the disease progressed (P < .001). Patients’ self-assessment in CDR 1 was worse than that in CDR 2 group (P = .045), and there were no significant differences between patients’ self-assessment in CDR 2 and that in CDR 0.5. Significant level: ***P < .001, ns: not significant.

The results of each item are shown in Table 2. In CDR 1, patients were aware of their problems in all the 16 items where discrepancy was observed. Concerning 2 items of problems with orientation in the neighborhood (#11) and mental calculation (#15), patients’ awareness was not significantly different from that of caregivers.

In CDR2, patients were not aware of their problems in remembering telephone call (#3), understanding conversations (#4), signing one’s name (#5), understanding the newspaper (#6), writing (#9), handling money (#10), orientation in the neighborhood (#11), practicing favorite hobbies (#13), communicating with people (#14), bladder control (#17), understanding the plot of a movie (#18), orientation in the house (#19), doing home activities (#20), and feeding oneself (#21), although caregivers noticed the patients’ deficits.

In mood and behavior domains, patients’ assessments were 3.3 ± 3.0 in CDR 0.5, 3.4 ± 2.9 in CDR 1 and 4.6 ± 4.0 in CDR 2 (Table 2). The results of each item are shown in Table 2.

Caregivers’ Evaluation

Caregivers’ assessments were 11.5 ± 10.5 (mean ± standard deviation) in CDR 0.5, 23.5 ± 9.7 in CDR 1 and 39.9 ± 14.7 in CDR 2 in intellectual functioning domain (Table 2 and Figure 1), and they were 3.7 ± 2.8 in CDR 0.5, 6.8 ± 3.4 in CDR 1, and 8.9 ± 2.6 in CDR 2 in mood and behavior domains (Table 2).

Anosognosia: Discrepancy Between Caregivers’ and Patients’ Assessment

In intellectual functioning domain,discrepancy between caregivers’ and patients’ assessment was significantly different among groups (P < .001), and post hoc analysis showed that caregiver’s assessment was significantly higher than patients’ assessment in the CDR 1 and CDR 2 groups (P < .001 in both groups) but not in the CDR 0.5 group (P = .389). The findings for each item are shown in Table 2. In CDR 0.5, discrepancy was significant only in mislaying (#8). In CDR 1, discrepancy was observed in 16 items except 6items: problems with signing one's name (#5), orientation inthe neighborhood (#11), mental calculation (#15), and bladder control (#17), orientation in the house (#19), and feeding oneself(#21). Concerning the last 2 items (#19 and #21), the caregivers answered that the patients were capable of these activities. In CDR 2, discrepancy was observed in all 22 items (Table 2 and Figure 1).

In mood and behavior domains, discrepancy between caregivers’ and patients’ assessment was significantly different among groups (P = .022), and post hoc analysis showed that caregivers’ assessments were significantly higher than patients’ assessment in the CDR 1 and CDR 2 groups (P < .001), but not in the CDR 0.5 group (P = .768). The findings for each item are shown in Table 2.

Patients’ Perspective and Caregivers’ Perspectives of Patients’ Distress

In CDR 0.5, according to patients’ perspectives, problems with remembering appointments (#12) were predictors of distress defined as patients’ scores of mood and behavior domain, whereas according to caregivers’ perspective, problems with remembering where things were left (#8) and doing clerical work (#22) were predictors.

In CDR 1, according to patients’ perspectives, problems with remembering appointments (#12), writing (#9), mental calculation (#15), and understanding the newspaper (#6) were predictors. Problems with writing (#9) were common predictors in assessment of patients and caregivers. According to caregivers’ perspectives, problems with remembering where things were left (#8) were a positive predictor, whereas problems with practicing favorite hobbies (#13) were a negative predictor.

In CDR 2, according to patients’ perspectives, problems with mental calculation (#15) and doing clerical work (#22) were predictors. Problems with doing clerical work (#22) were common predictors in the assessment of patients and caregivers. According to caregivers’ perspectives, problems with feeding oneself (#21) and bladder control (#17) were positive predictors, and problems with communicating with people (#14) was a negative predictor (Table 2).

Discussion

From patients’ perspectives, awareness of deficits remained until CDR 2, although awareness diminished as disease progressed. In CDR 0.5, patients’ assessments of function and those of caregivers were similar. In CDR 1, the patients were generally aware of their deficits even if their assessment was insufficient. In CDR 2, insufficient awareness of deficits remained and was related to the elemental cognition such as memory (#8, #12, and #16), and time and spatial orientation (#1 and #2). At the same time, it was also shown that the patients no longer retained self-awareness in many aspects. They lost awareness of deficits in activities requiring executive function such as handling money (#10), practicing favorite hobbies (#13), and doing home activities (#20). Metacognition is considered to be closely related to executive functions, 32 ,33 and it should be noted that self-awareness concerning executive function could deteriorate before self-awareness related to memory or orientation.

In CDR 2, deficits in self-awareness were also apparent in the activities regarding communication and social interaction: understanding conversations (#4), communicating with people (#14), understanding the newspaper for accessing information on society (#6) and understanding the plot of a movie that involves communication of characters (#18). Unawareness of communication deficits could be partly explained by a defense mechanism 34 in the desire to cling to social interaction.

Discrepancy was observed between patients’ and caregivers’ perspective in what patients felt distressed, adding to the difference between patients’ and caregivers’ assessment of patients’ deficits. From the patients’ perspective, patients in CDR 0.5 and 1 might feel distressed due to attenuated social interaction; difficulty with remembering appointments (#12) was chosen as a predictor of distress in CDR 0.5 and in CDR 1. Social interaction and network tend to become limited due to the disease, 35 and the patients may be aware of the difficulties in maintaining social interaction. Problems with writing (#9) and understanding the newspaper (#6) were also chosen in CDR 1. Those 2 are intellectual tasks related to communication. Writing is an important measure of communication, especially for patients who may have difficulty with face-to-face communication because of the deterioration of comprehension and language abilities. Newspapers are one of the useful tools to catch up with the world. Home delivery service of newspapers is common in Japan, and many elderly individuals habitually read newspapers.

Patients with AD might also be annoyed with awareness of deficits in intellectual tasks. 31 Patients in CDR 1 and 2 felt distressed as a result of awareness of problems with mental calculation (#15). Patients in CDR 2 also felt distressed as a result of awareness of deficits in clerical work (#22); in the Japanese version, the clerical work was limited to household budget management. The caregivers understood the patients’ distress concerning deficits in writing (#9, CDR 1) and deficits in doing clerical work (#22, CDR 2); however, they imagined that the patients in CDR 0.5 and 1 only felt distressed by awareness of deterioration of memory (#8 difficulties in remembering where things were left) and those in CDR 2 felt distressed by awareness of deterioration of basic activities of daily living in bladder control (#17) and feeding oneself (#21). Caregivers also thought that patients did not care about problems in practicing favorite hobbies (#13, CDR 1) or communicating with people (#14, CDR 2).

The results indicated that patients felt distressed by awareness of deficits, especially deficits in social interaction and intellectual work. The results also suggested that the patients would prefer to satisfy social needs rather than basic physiological need, which caregivers assumed to be patients’ concerns in CDR 2. Misunderstanding of these needs could lead to BPSD. The BPSD is not triggered solely by physiological factors, but rather reflects social environments in which the behavior occurs. 36 –38 Thus, modifying environmental factors could be beneficial approach to managing BPSD. As the relationship with caregivers is one of the most influential social environmental factors for the patients, modifying caregivers’ behaviors should be beneficial treatment of BPSD. 39 To the contrary, modifying patients’ awareness, for example, awareness-raising approaches would be inappropriate. Decline of abilities is inevitable for patients with AD, and the approach forces the patients to confront their deficits and could lead to adverse effects such as anxiety and lowering of self-esteem and motivation. 31,40 The essence of care as nonpharmacological intervention is interpersonal empathetic relationship. Empathy involves cognitive processes to understand others and situations analytically, 41 and cognitive empathy focuses on understanding what the patient needs based on the patients’ perspective. It could be an effective tool for cognitive empathy to analyze why patients feel distressed due to self-awareness of disease.

This study had some limitations. The questionnaire discrepancy method recognizes caregivers’ assessment as an objective standard, which could be biased by patient–caregiver relationship and caregivers’ factors such as depression and health status. This research was conducted in a small number of participants. For the next step, we are planning an interventional study to enhance the coping resources of caregivers with a larger number of participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Masamitsu Takatama, Geriatrics Research Institute and Hospital, Maebashi, and Rumi Shinohara and Yuko Tsunoda, at the Gunma University, Maebashi, for their support.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Yamaguchi is supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology, Japan (23300197 and 22650123), and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (H22-Ninchisho-Ippan-004) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

References

- 1. McGlynn SM, Kaszniak AW. When metacognition fails: impaired awareness of deficit in Alzheimer's disease. J Cogn Neurosci. 1991;3(2):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kotler-Cope S, Camp CJ. Anosognosia in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995;9(1):52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Starkstein SE, Sabe L, Chemerinski E, Jason L, Leiguarda R. Two domains of anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61(5):485–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vasterling JJ, Seltzer B, Watrous WE. Longitudinal assessment of deficit unawareness in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1997;10(3):197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vogeley K, Bussfeld P, Newen A, et al. Mind reading: neural mechanisms of theory of mind and self-perspective. Neuroimage. 2001;14(1 pt 1):170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kjaer TW, Nowak M, Lou HC. Reflective self-awareness and conscious states: PET evidence for a common midline parietofrontal core. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Decety J, Grezes J. The power of simulation: imagining one's own and other's behavior. Brain Res. 2006;1079(1):4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mimura M, Yano M. Memory impairment and awareness of memory deficits in early-stage Alzheimer's disease. Rev Neurosci. 2006;17(1-2):253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salmon E, Perani D, Herholz K, et al. Neural correlates of anosognosia for cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27(7):588–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amanzio M, Torta DM, Sacco K, et al. Unawareness of deficits in Alzheimer's disease: role of the cingulate cortex. Brain. 2011;134(pt 4):1061–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsuda H. Role of neuroimaging in Alzheimer's disease, with emphasis on brain perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(8):1289–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cavanna AE. The precuneus and consciousness. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(7):545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dickerson BC, Sperling RA. Large-scale functional brain network abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease: insights from functional neuroimaging. Behav Neurol. 2009;21(1):63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Starkstein SE, Chemerinski E, Sabe L, et al. Prospective longitudinal study of depression and anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harwood DG, Sultzer DL, Wheatley MV. Impaired insight in Alzheimer disease: association with cognitive deficits, psychiatric symptoms, and behavioral disturbances. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2000;13(2):83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kashiwa Y, Kitabayashi Y, Narumoto J, Nakamura K, Ueda H, Fukui K. Anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease: association with patient characteristics, psychiatric symptoms and cognitive deficits. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(6):697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spalletta G, Girardi P, Caltagirone C, Orfei MD. Anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms and disorders in mild Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29(4):761–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Black W, Almeida OP. A systematic review of the association between the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia and burden of care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16(3):295–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, et al. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(7):561–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cohen-Mansfield J, Libin A, Marx MS. Nonpharmacological treatment of agitation: a controlled trial of systematic individualized intervention. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(8):908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(8):734–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reisberg B, Ferris SH, Kluger A, Franssen E, Wegiel J, de Leon MJ. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): a historical perspective. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(1):18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, et al. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(1):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment—beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a Geriatric Depression Screening Scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17(1):37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith CA, Henderson VW, McCleary CA, Murdock GA, Buckwalter JG. Anosognosia and Alzheimer's disease: the role of depressive symptoms in mediating impaired insight. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000;22(4):437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakaaki S, Murata Y, Sato J, et al. Impact of depression on insight into memory capacity in patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(4):369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mimura M. Memory impairment and awareness of memory deficits in early-stage Alzheimer's disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;215(2):133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Migliorelli R, Teson A, Sabe L, et al. Anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease: a study of associated factors. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7(3):338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sato J, Nakaaki S, Murata Y, et al. Two dimensions of anosognosia in patients with Alzheimer's disease: reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Anosognosia Questionnaire for Dementia (AQ-D). Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(6):672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lai JM, Hawkins KA, Gross CP, Karlawish JH. Self-reported distress after cognitive testing in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(8):855–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shimamura AP. Toward a cognitive neuroscience of metacognition. Conscious Cogn. 2000;9(2 pt 1):313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clare L. Awareness in early-stage Alzheimer's disease: a review of methods and evidence. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43(pt 2):177–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mograbi DC, Brown RG, Morris RG. Anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease--the petrified self. Conscious Cogn. 2009;18(4):989–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fratiglioni L, Wang HX, Ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B. Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: a community-based longitudinal study. Lancet. 2000;355(9212):1315–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, Arean PA. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(20):2182–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O'Connor DW, Ames D, Gardner B, King M. Psychosocial treatments of behavior symptoms in dementia: a systematic review of reports meeting quality standards. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(2):225–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hauck WW. A non-pharmacological intervention to manage behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and reduce caregiver distress: design and methods of project ACT3. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(4):695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dietch JT, Hewett LJ, Jones S. Adverse effects of reality orientation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(10):974–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Decety J. The neuroevolution of empathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1231:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]