Abstract

Background

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation remains the recommended treatment for eligible patients with multiple myeloma (MM). Increasing the number of transplanted CD34+ cells shorten the time to hematopoietic reconstitution and increases the overall survival of patients. With the harvest of a sufficient CD34+ cell number being crucial, this study aimed to predict the factors that affect stem cell collection.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of 110 patients who were newly diagnosed with MM and underwent autologous HSC collection at Beijing Jishuitan Hospital between March 2016 and July 2022. Multiple factors were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U tests for between-group comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

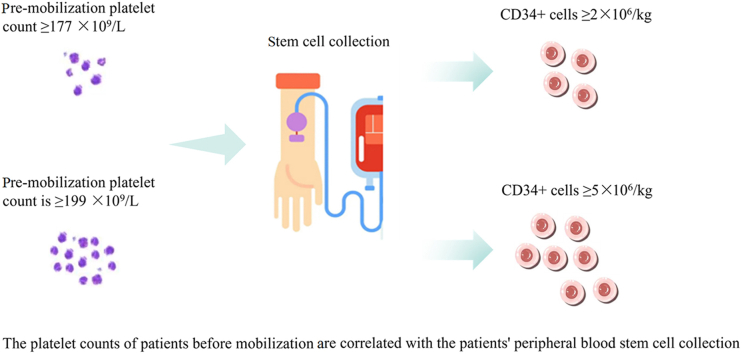

We found that patient age affected stem cell collection significantly; for patients younger than 55 years, the number of CD34+ cells harvested may be ≥ 2 × 106/L, is unlikely to reach 5 × 106/L. Platelet count at initial mobilization was a predictor of the number of CD34+ cells collected. Collection may fail when the platelet count at initial mobilization is below 177 × 109/L and may be excellent when it is higher than 199 × 109/L.

Conclusions

This finding could guide us to predict the approximate number of CD34+ cells collected in advance during autologous transplant mobilization for MM and to decide in advance whether to apply plerixafor to improve the number of HSCs collected.

Keywords: Platelet count, Hematopoietic stem cell collection, Multiple myeloma

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Age and pre-mobilization platelet count affect the number of stem cells collected.

-

•

Pre-mobilization platelet count may be predictive of CD34+ cell collection.

-

•

Plerixafor use in hematopoietic stem cell collection in patients with multiple myeloma can be better assessed.

Introduction

In the era of conventional chemotherapy, the clinical outcome of multiple myeloma (MM) was poor, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 30%.1 However, with the arrival of new drugs and treatment modalities, the nature of conventional treatment for MM has changed dramatically. The use of immunomodulatory agents and proteasome inhibitors, as well as monoclonal antibodies and autologous hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation, has greatly improved the remission rate of MM.2,3 Although there is a plethora of new drugs available for the treatment of MM, several studies have demonstrated that autologous HSC transplantation remains an integral part of the overall treatment and has an important place in patients with newly diagnosed MM who are eligible for transplantation.4, 5, 6 The number of CD34+ cells collected after autologous HSC mobilization is a key factor in the success of transplantation. The collection of an adequate number of CD34+ HSCs and their subsequent implantation patients help patients to better restore hematopoietic capacity, reduce the risk of infection, and improve overall survival rates.7, 8, 9

Currently, commonly used mobilization regimens comprise the use of cytokines (such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF]), chemotherapy followed by cytokines (such as cyclophosphamide [CTX] followed by G-CSF), or the C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) inhibitor, plerixafor. Of these, CTX plus G-CSF is a widely used HSC mobilization regimen for patients with MM. Although published literature on mobilization methods reports relatively good results, a sufficient number of HSCs is still not collected in 5–40% of patients awaiting transplantation due to a variety of reasons.10, 11, 12 Plerixafor has shown excellent stem cell mobilization and has few side effects, but its high cost of administration limits mobilization protocols that include this immunostimulant. It remains challenging to predict stem cell collection outcomes in advance for patients to determine whether plerixafor should be used. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the factors that influence the number of peripheral blood HSCs that can be collected.

Methods

Patients

We conducted a retrospective study of 110 patients with primary MM who underwent autologous HSC collection at the Department of Hematology, Beijing Jishuitan Hospital, from March 2016 to July 2022. All patients met the diagnostic criteria of the International Myeloma Working Group and were staged using the Durie–Salmon criteria and the International staging system (ISS). The main HSC mobilization regimen employed was CTX chemotherapy combined with G-CSF. Stem cells were mobilized with high-dose CTX at 3 g/m2 divided into two-days infusions. This was followed by 600 mg G-CSF injection on day 7 after CTX administration and continued for 4 days. After 10 days of CTX chemotherapy, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained using the monocyte isolation procedure.13 The percentage of cells expressing CD34 in connection to CD45+ cell and WBC counts was used to calculate the absolute number of CD34+ cells. A CD34+ count <2 × 106/kg was considered a poor collection, ≥2 × 106/kg was considered a adequate collection, and ≥5 × 106/kg was considered an excellent collection.14 Patient data collected comprised gender, age, disease type, Durie–Salmon stage, ISS stage, the presence or absence of lenalidomide use, disease status at mobilization, the presence or absence of diabetes, the number of treatment courses before mobilization, and counts for leukocytes, hemoglobin, and platelets prior to CTX mobilization.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS 25 software. A general description of the data was compiled first, and data that did not conform to a normal distribution were described by the median. Next, univariate ANOVA was performed, and the data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test for comparisons between groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 110 patients were included in this study, of which 59 (53.6%) were males and 51 (46.4%) were females. The median age was 54.41 (46.47–64.34) years. There were 49 patients (44.5%) aged ≤55 years and 61 patients (55.5%) aged >55 years. The numbers of immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgA, IgD, light chain type, and non-secretory type patients were 44, 25, 5, 31, and 5, respectively. The combined number of ISS stage I and II patients was 78, and 32 patients were classified as stage III. Thirty-nine patients had received previous treatment with lenalidomide, while 71 patients did not. Among the patients, 87 (79.1%) achieved complete response or very good partial response, while 23 (20.9%) achieved only partial response or below partial response. Twenty patients (18.2%) had diabetes mellitus. There were 78 patients (70.9%) who had previously received ≤4 cycles, while 32 (29.1%) had received >4 cycles. The poor, adequate rate of collection in these patients were 15.5% (17/110), 84.5% (93/110), and the non-excellent and excellent collection were 65.5% (72/110) and 34.5% (38/110), respectively. The median number of CD34+ cells obtained was 4.17 × 106/kg. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with multiple myeloma that underwent mobilization.

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 59 (53.6) |

| Female | 51 (46.4) |

| Age (years), | 54.4 ± 7.9 |

| ≤55, n (%) | 49 (44.5) |

| >55, n (%) | 61 (55.5) |

| Disease type, n (%) | |

| IgG type | 44 (40.0) |

| IgA type | 25 (22.7) |

| IgD type | 5 (4.5) |

| Light chain | 31 (28.2) |

| Non-secretory | 5 (4.5) |

| International staging system (ISS) stage, n (%) | |

| Stage 1 + 2 | 78 (70.9) |

| Stage 3 | 32 (29.1) |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| Non-lenalidomide regimens | 71 (64.5) |

| Lenalidomide-containing regimens | 39 (35.5) |

| Disease stage, n (%) | |

| ≤ Partial response | 23 (20.9) |

| Complete response + very good partial response | 87 (79.1) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | |

| Yes | 20 (18.2) |

| No | 90 (81.8) |

| Cycles before mobilization, n (%) | |

| ≤4 | 78 (70.9) |

| >4 | 32 (29.1) |

| CD34+ count, n (%) | |

| <2 × 106/kg (poor mobilization) | 17 (15.5) |

| ≥2 × 106/kg | 93 (84.5) |

| <5 × 106/kg | 72 (65.5) |

| ≥5 × 106/kg (excellent mobilization) | 38 (34.5) |

Ig: Immunoglobulin

Univariate analysis to predict the factors influencing peripheral blood HSC collection

Information on peripheral blood HSC collection in these 110 patients is summarized in Table 2. Univariate ANOVA revealed that an age >55 years was a risk factor that contributed significantly to mobilization failure (P = 0.025), although age did not affect the rate of excellent collections of peripheral blood stem cells (P = 0.100). In addition, sex, disease type, ISS stage, previous exposure to lenalidomide, disease status at the time of mobilization, diabetes mellitus, and previous treatment >4 courses had no effect on the success of peripheral blood stem cell collection or the ability to achieve excellent collection.

Table 2.

Information on the collection of peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells from patients.

| Characteristics | n | Collected CD34+ cells ( × 106/kg), Mean (P25, P75) | ≥2 × 106/kg, n (%) | ≥5 × 106/kg, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 59 | 3.88 (2.13, 7.22) | 49 (83.1) | 19 (32.2) |

| Female | 51 | 3.68 (2.65, 7.33) | 45 (88.2) | 19 (37.3) |

| P value | 0.688 | 0.442 | 0.578 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤55 | 49 | 4.25 (2.96, 7.96) | 46 (93.9) | 21 (42.9) |

| >55 | 61 | 3.24 (2.28, 5.77) | 47 (78.7) | 17 (27.9) |

| P value | 0.026 | 0.025 | 0.100 | |

| Disease type | ||||

| IgG type | 44 | 4.06 (2.59, 7.53) | 37 (84.1) | 17 (38.6) |

| IgA type | 25 | 4.25 (2.55, 7.68) | 24 (96) | 10 (40) |

| IgD type | 5 | 3.24 (2.17, 3.93) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Light chain | 31 | 3.12 (2.00, 6.84) | 23 (74.2) | 9 (29) |

| Non-secretory | 4 | 4.11 (3.25, 8.37) | 4 (100) | 2 (50) |

| P value | 0.550 | 0.173 | 0.457 | |

| International Staging System stage | ||||

| Stage 1 + 2 | 78 | 3.77 (2.67, 6.65) | 69 (88.5) | 24 (30.8) |

| Stage 3 | 32 | 3.94 (2.04, 8.15) | 25 (78.1) | 14 (43.8) |

| P value | 0.800 | 0.272 | 0.193 | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Non-lenalidomide regimens | 39 | 3.4 (2.09, 6.48) | 31 (79.5) | 13 (33.3) |

| Lenalidomide regimens | 71 | 4.17 (2.67, 7.33) | 63 (88.7) | 25 (35.2) |

| P value | 0.142 | 0.188 | 0.843 | |

| Disease stage | ||||

| ≤ Partial response | 23 | 3.5 (2.08, 7.36) | 18 (78.3) | 8 (34.8) |

| Complete response + very good partial response | 87 | 4.11 (2.65, 7.22) | 76 (87.4) | 30 (34.5) |

| P value | 0.330 | 0.443 | 0.979 | |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 20 | 3.53 (2.09, 7.54) | 16 (80) | 8 (40) |

| No | 90 | 3.89 (2.59, 7.02) | 77 (85.6) | 30 (33.3) |

| P value | 0.842 | 0.780 | 0.571 | |

| Cycles before mobilization | ||||

| ≤4 | 78 | 3.77 (2.48,6.51) | 67 (85.9) | 25 (32.1) |

| >4 | 32 | 4.40 (2.60, 7.72) | 26 (81.3) | 13 (40.6) |

| P value | 0.135 | 0.747 | 0.390 | |

Ig: Immunoglobulin.

Initial mobilized platelet count affects the success rate of hematopoietic stem cell collection and good collection rate

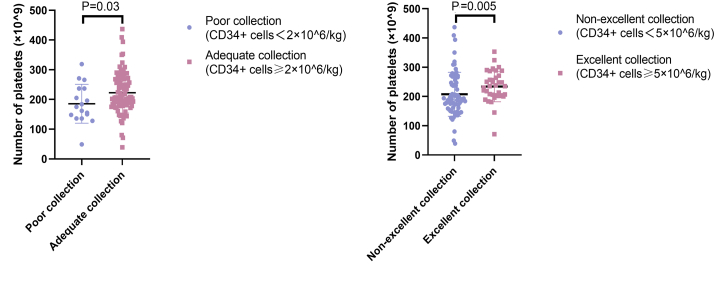

During our statistical analyses, we discovered an interesting phenomenon: the number of platelets initially mobilized (i.e., the number of platelets present before the use of CTX) correlated with the number of peripheral blood HSCs collected from the patients. As shown in Figure 1, when the number of peripheral blood HSCs collected was <2 × 106/kg, the corresponding count for initially mobilized platelets was also significantly lower (P = 0.030) than that of patients with ≥2 × 106/kg cells collected. Conversely, the initially mobilized platelet count was also significantly higher (P = 0.005) in patients with a harvest of ≥5 × 106/kg HSCs than in patients with a <5 × 106/kg harvest. We compared whether there was also an association between the number of leukocytes and hemoglobin present in patients before the use of CTX and the number of peripheral blood HSCs ultimately harvested, but the results indicated no significant associations (for either adequate or excellent collections). These values are shown in Table 3.

Figure 1.

The pre-mobilization platelet counts of patients were correlated with their peripheral blood stem cell collection. (A) The platelet counts at mobilization were higher in patients with adequate collection than in those with poor collection; (B) The platelet counts at mobilization were significantly higher in patients with excellent collection than in those with non-excellent collection.

Table 3.

Effects of pre-mobilization leukocyte, hemoglobin, and platelet counts on the success and excellent collection rate of hematopoietic stem cells.

| Characteristics | CD34+ cells <2 × 106/kg | CD34+ cells ≥2 × 106/kg | CD34+ cells ≥5 × 106/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte count at initial mobilization | 4.948 × 109/L | 5.136 × 109/L | 5.768 × 109/L |

| P value | – | 0.136 | 0.057 |

| Hemoglobin count at initial mobilization | 120.5 g/L | 125.9 g/L | 128.5 g/L |

| P value | – | 0.137 | 0.189 |

| Platelet count at initial mobilization | 185.5 × 109/L | 222.6 × 109/L | 234 × 109/L |

| P value | – | 0.030 | 0.005 |

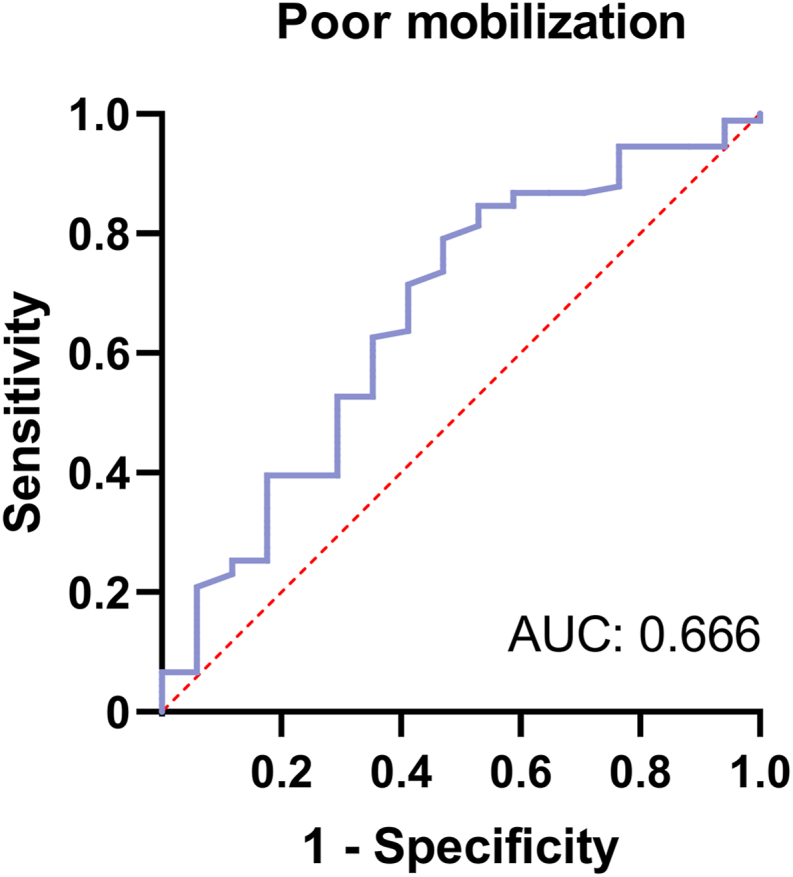

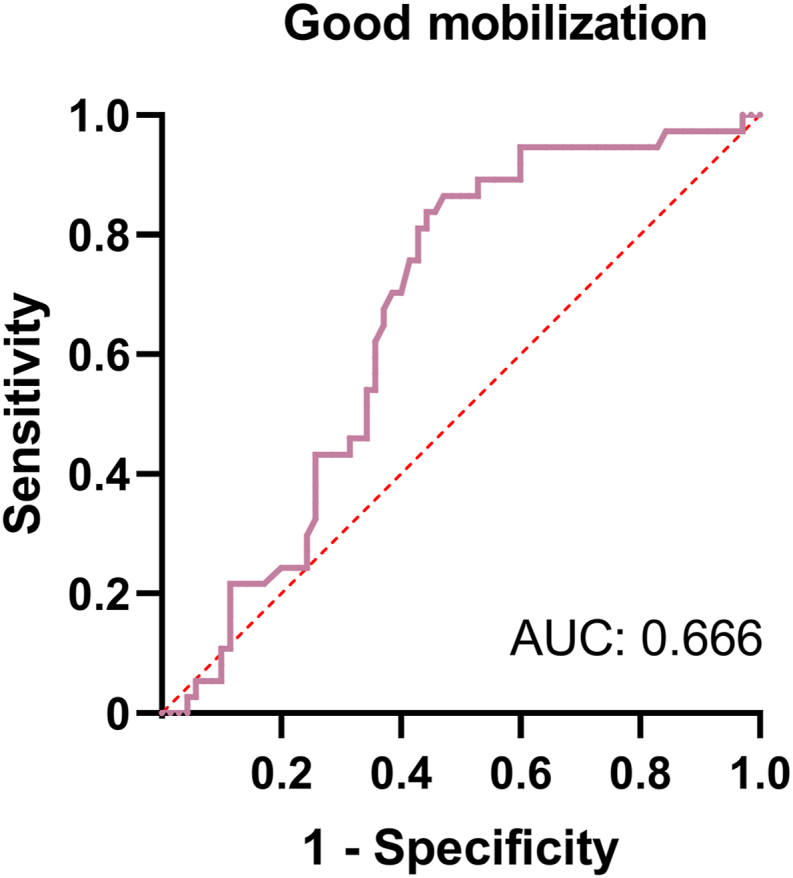

To understand how platelet count can influence the collection of peripheral blood HSCs, we evaluated the pre-mobilization platelet level of patients and used it as an indicator to estimate the probability of exceeding 2 × 106/kg and exceeding 5 × 106/kg CD34+ cells at the time of HSC collection. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to define the cutoff value for this indicator and consisted of a set of plots representing the combination of sensitivity and 1-specificity as a function of the value of a specific cutoff point. Usually, the cutoff value is defined as the value closest to the upper left corner of the plot, where sensitivity plus specificity is maximized for all indicators. In addition, the accuracy of indicators in the ROC curve can be assessed using the area under the curve (AUC), which ranges from 0.5 to 1, with accuracy being greatest in the larger area. Figure 2 shows that the cutoff value for predicting the platelet count required to mobilize over 2 × 106/kg CD34+ for HSC harvesting was 177 × 109/L (AUC = 0.666, 51.9% sensitivity, 81.3% specificity). For the mobilization of over 5 × 106/kg CD34+ at the time of HSC collection, the platelet count cutoff value was calculated as 199 × 109/L (AUC = 0.666, 56.3% sensitivity, 76.9% specificity), as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of platelet count for predicting adequate mobilization. The optimal cutoff value of platelets is 177 × 109/L. Area under the curve (AUC) is 0.666.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of platelet count for predicting excellent mobilization. The optimal cutoff value of platelets is 199 × 109/L. Area under the curve (AUC) is 0.666.

Subsequently, we performed a multifactorial analysis of factors that influence the number of HSCs harvested, including the platelet count prior to mobilization as one of these factors. The results are shown in Table 4, Table 5. We discovered that age of ≤55 years and a pre-mobilization platelet count ≥177 × 109/L had significant effects on the success of HSC collection. Other patient parameters, such as sex, whether or not diabetes was present, and whether lenalidomide had been used, did not affect the number of HSCs harvested during adequate collections. In the case of excellent collections, patient age and pre-mobilization platelet count similarly had a significant influence: ≥5 × 106/kg peripheral blood HSCs can predictably be collected when the age of the patient is ≤ 55 years or the pre-mobilization platelet count is ≥ 199 × 109/L. Again, other parameters did not affect harvest figures of excellent collections.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of the success of peripheral CD34+ cell collections.

| Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≤55 years | 4.225 | 1.053–16.951 | 0.042 |

| Sex | 0.627 | 0.186–2.110 | 0.451 |

| Platelet count (177 × 109/L) | 0.228 | 0.069–0.753 | 0.015 |

| Diabetes | 3.598 | 0.092–13.459 | 0.057 |

| Use lenalidomide | 1.699 | 0.367–7.282 | 0.475 |

| Four Cycles before mobilization | 2.984 | 0.746–11.945 | 0.122 |

CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratio.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of the excellent collection of peripheral CD34+ cells.

| Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≤55 years | 1.770 | 0.736–4.253 | 0.202 |

| Sex | 0.659 | 0.273–1.590 | 0.353 |

| Platelet count (199 × 109/L) | 0.175 | 0.067–0.459 | 0 |

| Diabetes | 0.686 | 0.225–2.090 | 0.508 |

| Use lenalidomide | 1.001 | 0.382–2.623 | 0.998 |

| Four Cycles before mobilization | 0.753 | 0.284–2.000 | 0.570 |

CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratio.

Discussion

In patients with primary MM, autologous HSC transplantation (ASCT) after induction therapy is effective at improving disease-free and overall survival.14,15 It is important to perform HCS transplantation after induction, and the number of transfused CD34+ HSCs play an important role in the clinical outcome of ASCT. Therefore, it is crucial to improve the HSC harvest yield to increase the success rate of transplantation. Our results found that gender, disease subtype, ISS stage, treatment regimen, disease status, number of sessions, and presence of diabetes did not significantly affect CD34+ cell harvest yield, success rate, or quality, which aligns with the findings of some previous reports.16,17 In contrast, when patients were ≤55 years old, the number of CD34+ cells collected, and the collection success rate were better than for those aged >55 years old. This demonstrated that younger patients might have a better reserve capacity for HSCs, so more HSCs could be released when mobilized for collection. The results further indicate that, although the number of CD34+ cells collected would be slightly lower in patients that made previous use of lenalidomide induction chemotherapy than in patients that did not, the use of lenalidomide did not affect the overall success and excellent rates of HSC collection, corresponding with previous reports.18,19

A classical roadmap of the hematopoietic hierarchy has been established for many years and has become the dogma of stem cell research for most adult stem cell types, including HSCs. However, with the recent development of new technologies, our understanding of hematopoiesis has broadened, and our description of the developmental route of HSCs has evolved. Megakaryocytes are now known to differentiate from HSCs directly, suggesting that megakaryocyte differentiation can bypass the stages of multipotent, common myeloid, and megakaryocyte–erythrocyte progenitors,20,21 which differs from traditional views. It is worth noting that there is a class of HSCs that only produces megakaryocytes/platelets.22 The number of platelets in vivo may, therefore, indirectly reflect the number of HSCs in vivo, i.e., the number of platelets can act as a simple criterion for evaluating the number of HSCs present. We found that when the pre-mobilization platelet count of a patient was below the calculated threshold (although the counts did not meet the diagnostic criteria for thrombocytopenia), the patient's CD34+ cell reserve was also not as high as expected; this poses a risk of collection failure or not collecting a sufficient number of CD34+ cells, which impacts subsequent transplantation.

Plerixafor is a selective and reversible CXCR4 inhibitor. It binds to CXCR4 and blocks its interaction with stromal cell-derived factor 1 chemokines, which stimulates the release of stem cells from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood.23,24 Plerixafor can greatly increase the number of HSCs collected, so pre-emptive administration of plerixafor in patients who are at high risk of mobilization failure has been considered.25 An increase in the number of CD34+ cells collected contributes to the success of the procedure and shortens the duration thereof, which reduces both patient suffering and the total cost of the mobilization phase of treatment.26,27 With the gradual application of plerixafor, it has become particularly important to predict HSC collection outcomes. Previously, the need for preemptive intervention with plerixafor has been established by obtaining the pre-collection CD34+ count after mobilization protocols with G-CSF and chemotherapy. However, in view of our data analysis, we propose that a pre-mobilization platelet count of patients may offer a novel method for predicting whether the CD34+ yield will meet expectations or not. The procedure is convenient, requiring only a routine blood test, and it provides a prediction earlier than a pre-collection CD34+ cell count would, which may help clinicians to gain a clearer indication of whether plerixafor is required to increase the mobilization count. In addition, this method reduces the mobilization pain and eases the financial burden on patients.

In summary, our retrospective study conducted univariate and multifactorial analyses to investigate factors that may affect the number of HSCs collected during mobilization. Both a patient age of fewer than 55 years and a sufficient pre-mobilization platelet count were strongly associated with favorable HSC yield. In particular, a pre-mobilization platelet count may be a novel predictor of CD34+ collection, which has not been reported previously. The predictive efficacy of this index is not that high at present, as the small number of cases available for analysis in our single-center study proved to be a limitation. The study population could be expanded in the future to improve data acquisition and statistical analysis.

Funding

None.

Author contributions

Li Bao, Kai Sun, and Yuan Chen contributed to the study design. Li Bao, Kai Sun, and Yuan Chen wrote the report. Shan Gao, Yutong Wang, Minqiu Lu, Lei Shi, Qiuqing Xiang, Lijuan Fang, Yuehua Ding, Mengzhen Wang, Xi Liu, Xin Zhao, Bin Chu, and Li Bao provided the patients. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The ethical approval for the study was provided by Beijing Jishuitan Hospital Ethics Committee (The ID is 20210902, Preparation No. 02).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- 1.Kumar S.K., Rajkumar S.V., Dispenzieri A., et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar S.K., Rajkumar V., Kyle R.A., et al. Multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson K.C. The role of immunomodulatory drugs in multiple myeloma. Semin Hematol. 2003;40:23–32. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voorhees P.M., Kaufman J.L., Laubach J., et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the GRIFFIN trial. Blood. 2020;136:936–945. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020005288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreau P., Attal M., Hulin C., et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:29–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa L.J., Chhabra S., Medvedova E., et al. Daratumumab, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone with minimal residual disease response-adapted therapy in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:2901–2912. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeh J.C., Shank B.R., Milton D.R., et al. Adverse prognostic factors for morbidity and mortality during peripheral blood stem cell mobilization in patients with light chain amyloidosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:815–819. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.11.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brioli A., Perrone G., Patriarca F., et al. Successful mobilization of PBSCs predicts favorable outcomes in multiple myeloma patients treated with novel agents and autologous transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:673–678. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreb J.S., Byrne M., Shugarman I., et al. Poor peripheral blood stem cell mobilization affects long-term outcomes in multiple myeloma patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation. J Clin Apher. 2018;33:29–37. doi: 10.1002/jca.21556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giralt S., Stadtmauer E.A., Harousseau J.L., et al. International myeloma working group (IMWG) consensus statement and guidelines regarding the current status of stem cell collection and high-dose therapy for multiple myeloma and the role of plerixafor (AMD 3100) Leukemia. 2009;23:1904–1912. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ataca A.P., Bakanay O.S., Demirer T. How to manage poor mobilizers for high dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation? Transfus Apher Sci. 2017;56:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahin U., Demirer T. Current strategies for the management of autologous peripheral blood stem cell mobilization failures in patients with multiple myeloma. J Clin Apher. 2018;33:357–370. doi: 10.1002/jca.21591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croop J.M., Cooper R., Seshadri R., et al. Large-scale mobilization and isolation of CD34+ cells from normal donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:1271–1279. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Child J.A., Morgan G.J., Davies F.E., et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1875–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fermand J.P., Katsahian S., Divine M., et al. High-dose therapy and autologous blood stem-cell transplantation compared with conventional treatment in myeloma patients aged 55 to 65 years: long-term results of a randomized control trial from the Group Myelome-Autogreffe. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9227–9233. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhary L., Awan F., Cumpston A., et al. Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization in multiple myeloma patients treat in the novel therapy-era with plerixafor and G-CSF has superior efficacy but significantly higher costs compared to mobilization with low-dose cyclophosphamide and G-CSF. J Clin Apher. 2013;28:359–367. doi: 10.1002/jca.21280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goker H., Ciftciler R., Demiroglu H., et al. Predictive factors for stem cell mobilization failure in multiple myeloma patients: a single center experience. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;59 doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2019.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowan A.J., Stevenson P.A., Green D.J., et al. Prolonged lenalidomide therapy does not impact autologous peripheral blood stem cell mobilization and collection in multiple myeloma patients: a single-center retrospective analysis. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27(661):e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson P.G., Blood E., Mitsiades C.S., et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., Gao S., Xia J., et al. Hematopoietic hierarchy - an updated roadmap. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:976–986. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Notta F., Zandi S., Takayama N., et al. Distinct routes of lineage development reshape the human blood hierarchy across ontogeny. Science. 2016;351:aab2116. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrelha J., Meng Y., Kettyle L.M., et al. Hierarchically related lineage-restricted fates of multipotent haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2018;554:106–111. doi: 10.1038/nature25455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin C., Bridger G.J., Rankin S.M. Structural analogues of AMD3100 mobilise haematopoietic progenitor cells from bone marrow in vivo according to their ability to inhibit CXCL12 binding to CXCR4 in vitro. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:326–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fricker S.P. Physiology and pharmacology of plerixafor. Transfus Med Hemotherapy. 2013;40:237–245. doi: 10.1159/000354132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arora S., Majhail N.S., Liu H. Hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization for autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma in contemporary era. Clin Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. 2019;19:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varmavuo V., Silvennoinen R., Anttila P., et al. Cost analysis of a randomized stem cell mobilization study in multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:1653–1659. doi: 10.1007/s00277-016-2772-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veltri L., Cumpston A., Shillingburg A., et al. Hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization with “just-in-time” plerixafor approach is a cost-effective alternative to routine plerixafor use. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1785–1792. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.