Highlights

-

•

The study demonstrated the existence of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) using transcriptomic data and clinical samples.

-

•

Results showed that B cells and TLS signature scores were associated with better outcome and early pathological staging in NPC patients.

-

•

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis uncovered five distinct B cell subsets in NPC, with the BC-4 cluster associated with poor outcomes and BC-0 cluster associated with better outcomes.

-

•

B cells and TLS may serve as prognostic biomarkers for NPC patients, and our findings demonstrate the functional importance of distinct B cell subsets in the prognosis of NPC.

Keywords: Single cell sequencing, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, B cells, Tertiary lymphoid structure

Abstract

Objective

Transcriptomic characteristics and prognosis of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) and infiltrating B cells in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) remain unclear. Here, NPC transcriptomic data and clinical samples were used to investigate the role of infiltrating B cells and TLS in NPC.

Methods

We investigated the gene expression and infiltrating immune cells of NPC patients and further investigated the clinical relevance of B cell and TLS signatures. Transcriptional features of infiltrating B cell subsets were revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis. Immunohistochemical (IHC) and HE staining were performed to validate the clinical relevance of infiltrating B cells and TLS in NPC samples.

Results

27 differentially expressed immune-related genes (IRGs) associated with prognosis were identified, including B cell marker genes CD19 and CD79B. The higher B cells and TLS signature scores were associated with better outcomes and early pathological staging in 88 NPC patients. ScRNA-seq identified five distinct B cell subsets in NPC, including the BC-4 cluster associated with poor outcomes and the BC-0 cluster associated with better outcomes. EBV infection was positively associated with the formation of TLS. Furthermore, experimental results showed that the infiltration of B cells in NPC tissues was higher than that of normal tissues, and the density of TLS in an early stage of NPC was higher than that in advanced-stage TLS.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate the functional importance of distinct B cell subsets in the prognosis of NPC. Additionally, we confirmed that B cells and TLS may serve as prognostic biomarkers of survival for NPC patients.

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a common head and neck cancer with high invasive and metastatic potential, primarily in Southeast Asia and North Africa, of which 75% of the differentiated types are associated with EBV infection [1,2]. In addition, due to factors such as deep anatomical location, complex structure, low pathological differentiation, and easy metastasis, approximately 70% of patients with NPC have reached the local advanced stage at the time of initial diagnosis [3]. NPC is sensitive to radiotherapy, and radiotherapy as the leading treatment combined with synchronous chemotherapy is the main treatment for locally advanced NPC at present. However, patients with intermediate and advanced stages often have recurrence and metastasis, and the mortality rate is still relatively high [4]. Therefore, it is of great urgency to investigate the mechanisms of NPC pathogenesis, discover effective diagnostic biomarkers associated with NPC prognosis, and find more effective therapeutic targets.

In recent years, tumor immunotherapy has achieved great success in clinical treatment, but there are still some patients who cannot benefit [5]. Previous studies have demonstrated the great potential of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in the occurrence, development, and treatment of tumors [6]. The present studies mainly focus on the anti-tumor function of tumor-infiltrating T cells, which found that T cells were associated with the prognosis for NPC [7]. Notably, B cells play a crucial role in anti-tumor immunity [8]. Recent studies found that tumor-infiltrating B cells improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma [9], [10], [11]. On the contrary, Shabnam Shalapour et al. determined that immunosuppressive plasma cells impede T cell-dependent immunogenic chemotherapy, indicating infiltrating B cells can play a pro-tumor function through immunosuppressive B cell subsets [12], [13], [14]. Those findings reveal the antior pro-tumor functions of distinct B cell subpopulations. Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) are ectopic lymphoid organs consisting of B cell-rich areas, which are associated with the abundance and functional state of B cells in TME, and infiltrating B cells and/or TLS are considered useful prognostic or predictive biomarkers [15]. However, the features of infiltrating B cells and TLS in NPC remain unclear.

In this study, bioinformatics data mining was performed on multiple public datasets of NPC, including microarray, RNA-seq and scRNA-seq data. Here, we evaluated the predictive values of prognosis for immune-related genes (IRGs), infiltrating immune cells, and TLS in NPC. scRNA-seq analysis was further used to reveal the transcription characteristics and prognosis of two distinct infiltrating B cell subpopulations in NPC. Furthermore, we determined that EBV infection was positively associated with the formation of TLS. In addition, our experimental results showed that the infiltration of B cells in NPC tissues was higher than that of normal tissues, and the density of TLS in an early stage of NPC was higher than that in advanced stage.

Method and materials

Data source

Five RNA microarray datasets (GSE12452, GSE13597, GSE53819, GSE61218, and GSE64634), including a total of 96 NPC tumors and 41 normal samples, and one high-throughput RNA sequencing dataset (GSE102349), including 113 NPC tumor samples, and one single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset (GSE150430), including 15 NPC tumor samples, were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (Table 1) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Immune-related genes (IRGs) were downloaded from the ImmPort database (https://www.immport.org/shared/home) [16]. Clinical samples were provided by the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University. All patients provided informed consent for the collection of samples, and this project was approved by the Institutional Review Board (approval number 2023-KT-44).

Table 1.

The enrolled datasets in the current study.

The characteristics of 113 NPC patients from GSE102349 cohort were shown in Table 2. The median age of patients is 45.5 years old. Eighty-six (76.1%) patients were male, 26 (23.0%) patients were female and 1 (0.9%) patient was unknow gender. According to the WHO classification criteria, 7 (6.2%) patients had stage I-II disease, and 66 (58.4%) patients had stage III-IV disease and 40 (35.4%) patients had unknow stage. Eighty-five (75.2%) patients’ histologic type were non-keratinizing differentiated carcinoma, 22 (19.5%) patients were non-keratinizing undifferentiated carcinoma and 6 (5.3%) patients’ histologic type were unknow.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of total 113 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

| Characteristics | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Total case | 113 |

| Age | |

| Median, range (25th percentile-75th percentile) | 45.5 (39–54) |

| HBV infection status | |

| Negative | 90 (79.6%) |

| Positive | 16 (14.2%) |

| Unavailable | 7 (6.2%) |

| Smoking history | |

| Smokers | 32 (28.3%) |

| Non-smokers | 46 (40.7%) |

| Unknown | 35 (31.0%) |

| Histologic type | |

| Non-keratinizing carcinoma, differentiated | 85 (75.2%) |

| Non-keratinizing carcinoma, undifferentiated | 22 (19.5%) |

| Unknown | 6 (5.3%) |

| HCV infection status | |

| Positive | 1 (0.9%) |

| Negative | 98 (86.7%) |

| Unknown | 14 (12.4%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 86 (76.1%) |

| Female | 26 (23.0%) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9%) |

| Clinical stage | |

| Stage I | 5 (4.4%) |

| Stage II | 2 (1.8%) |

| Stage III | 41 (36.3%) |

| Stage IV | 25 (22.1%) |

| Unknown | 40 (35.4%) |

RNA microarray data analysis

SVAR package [17] was conducted to combine the gene expression data from the five data sets to adjust for batch effects. The Limma R package [18] was used to identify the differential expression genes (DEGs) between the NPC tumor and normal samples. Genes were considered DEGs when adjusted p-value 〈 0.05 and |logFC| 〉 1.

Single cell RNA sequencing data analysis

Cells were filtered out when they had >20% mitochondrial genes. After quality control and filtering, a total of 46,001 cells were selected for analysis. Gene expression was normalized, clustering and dimension reduction analysis using the Seurat R package [19]. Major cell clusters were identified, including T cells, B cells, myeloid cells, and epithelial cells, or cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) clusters. The ‘FindAllmarkers’ and ‘Findmarkers’ functions were used to identify DEGs. Genes were considered DEGs when the adjusted p-value 〈 0.05 and |ave_logFC| 〉 0.5. The ‘AddModuleScore’ function was used to calculate the gene signature scores. CellChat R package was utilized to infer the intercellular communication pathways [20].

Pathways enrichment analysis

The ClusterProfiler [21] and the fgsea R package [22]were used for pathway enrichment analysis. The code and tutorial could be obtained from the website (http://yulab-smu.top/biomedical-knowledge-mining-book). Adjusted p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Analysis of the abundances of immune cells

The CIBERSORT R package [23] was used to calculate the proportions of 22 immune cells based on RNA microarray data from 96 tumor and 41 normal samples. Only cases with a p-value < 0.05 were selected for the following analysis. The TIMER method was used to calculate the proportions of immune cells based on RNA-seq data from 113 tumor samples using the IOBR R package [24].

Survival analysis

The survminer and survival R packages were used for the survival analysis based on the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method. 88 NPC cases with completed a survival time were selected for the survival analysis. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant via the log-rank test.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

According to the manufacturer's instructions, tissues were embedded and sectioned, and sections were stained with a CD19 antibody using the immunohistochemistry kit. In brief, tissue sections were deparaffinized by xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed in sodium citrate buffer at 100 °C for 15 min and then cool down to room temperature. 3% H2O2 was used to block the activity of endogenous peroxidase. 5% BSA was used to block nonspecific binding sites at room temperature for 30 min. Primary antibody CD19 (ab134114, 1:200, Abcam, UK) was incubated at 4 °C for 12 h, and rabbit mAb IgG control (1:200) was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. DAPI was used to stain the nuclei. The images were taken with a microscope and analyzed by image J software.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining

Tissues were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded, and sectioned (3 μm thick) in paraffin, and HE staining was carried out following the manufacturer's instructions. Then the sample sections were observed with a light microscope.

Statistical analysis

Single-factor analysis was calculated by the univariate Cox proportional risk regression model. The Wilcox test was used for comparisons between two groups. The statistical analysis was performed by R software. And the ggplot2 R package [25] was used for visualization. P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. In this study, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, and p < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Result

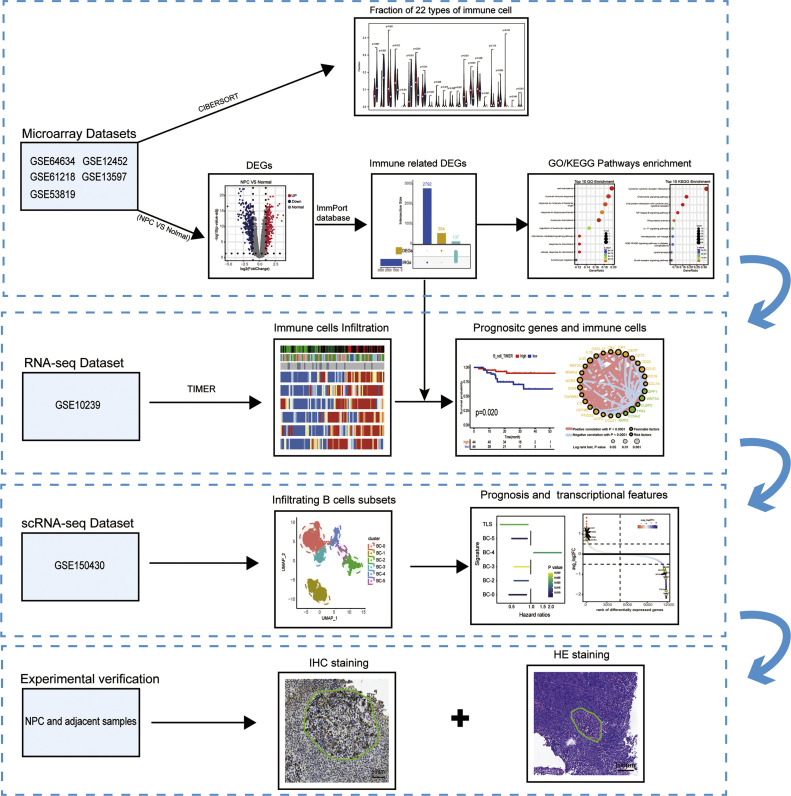

Workflow of this study

In this study, we collected bulk transcriptome and single-cell transcriptome from publicly available datasets (GSE12452, GSE13597, GSE53819, GSE61218, GSE64634, GSE102349, GSE150430), as well as clinical samples from a retrospective cohort. We utilized bioinformatics analysis to investigate the mechanisms of B cells and TLS in NPC and validated by immunohistochemical staining. The overall study design and workflow were illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram describing the data analysis process of this study.

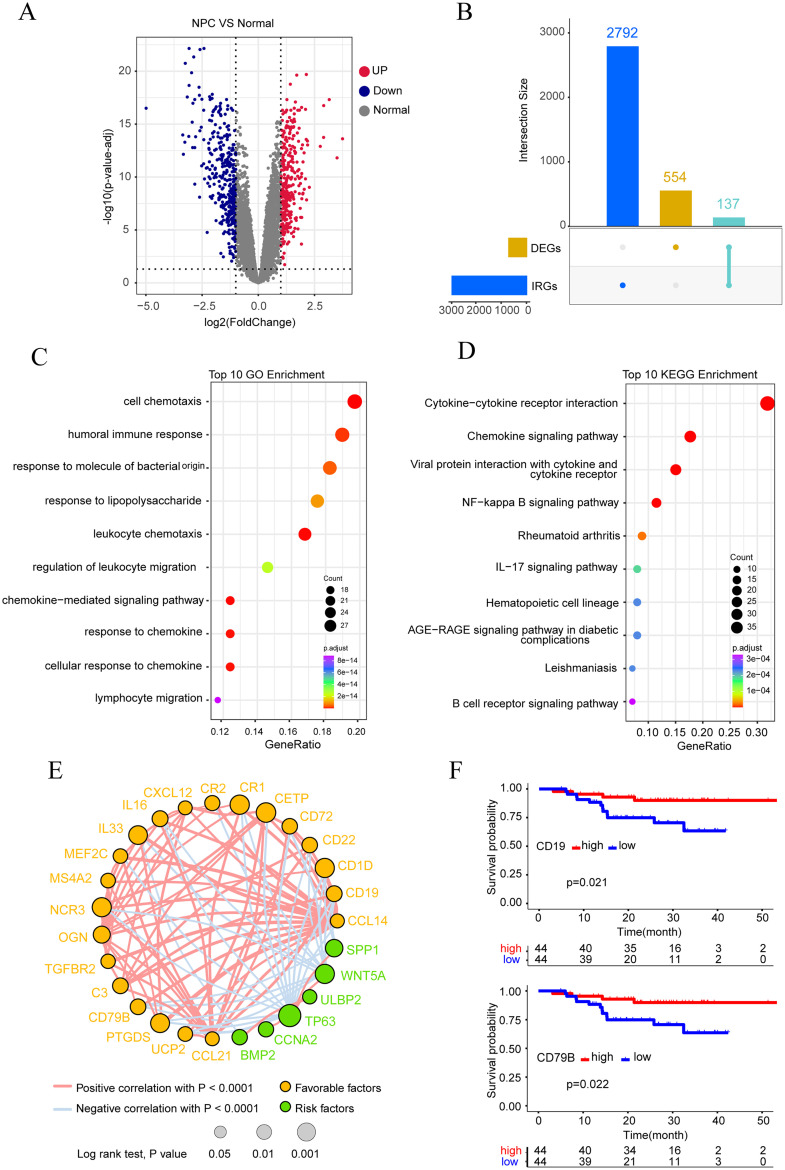

Comparison of transcriptional characteristics between NPC and normal tissues

To explore attractive potential targets for NPC prevention and treatment, we investigated differentially expressed genes between normal nasopharyngeal tissues and NPC tissues using microarray-based transcriptome data. Differential expression analysis showed a total of 691 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including 317 up-regulated and 374 down-regulated genes (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B, 137 differentially expressed IRGs were obtained (Fig. 2B). On 137 differentially expressed IRGs, GO (Gene Ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) analyses were carried out, and the top 10 pathway enrichments were displayed, respectively.The analysis results showed the enrichment of B cell-related signaling pathways such as humoral immune response and B cells receptor-related pathways (Fig. 2C and D), which suggests that tumor-infiltrating B cell may have a close relationship with NPC. To further screen for differentially expressed IRGs related to prognosis, we downloaded 113 NPC transcriptome sequencing data sets from GEO, of which 88 patients had complete survival information. According to the expression of each differentially expressed IRG, the patients were divided into two groups: high and low, and then Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and correlation analysis were performed, and a total of 27 differentially expressed IRGs related to the prognosis of NPC were obtained. CD19, CD79B, CR2, IL33, CXCL12, CCL14, CR1, MEF2C, CD22, CCL21, CD1D, TGFBR2, IL16, UCP2, PTGDS, OGN, NCR3, CD72, CETP, C3, and MS4A2 are associated with good a prognosis in NPC patients, while SPP1, WNT5A, ULBP2, TP63, CCNA2 and BMP2 are associated with poor prognosis in NPC patients (Fig. 2E). It is worth noting that two B cell marker genes, CD79B and CD19, are included (Fig. 2F). This further indicates that tumor-infiltrating B cells play a key role in NPC and suggests that tumor-infiltrating B cells may be associated with the prognosis of NPC.

Fig. 2.

Analysis results showed differential genes, pathway enrichment and screening of key immune-related genes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and nasopharyngeal tissue. (A)The volcano map showed 691 differentially expressed genes, including 317 up-regulated genes and 374 down-regulated genes. (B) The intersection diagram showed 137 differentially expressed IRGs. (C) GO enrichment analysis for 137 IRGs revealed the top ten terms. (D) Top ten in KEGG enrichment analysis for 137 IRGs were shown. (E) The Circle map depicted 27 genes associated with prognosis and their correlation. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed infiltration of B cells can prolong the survival of NPC patients.

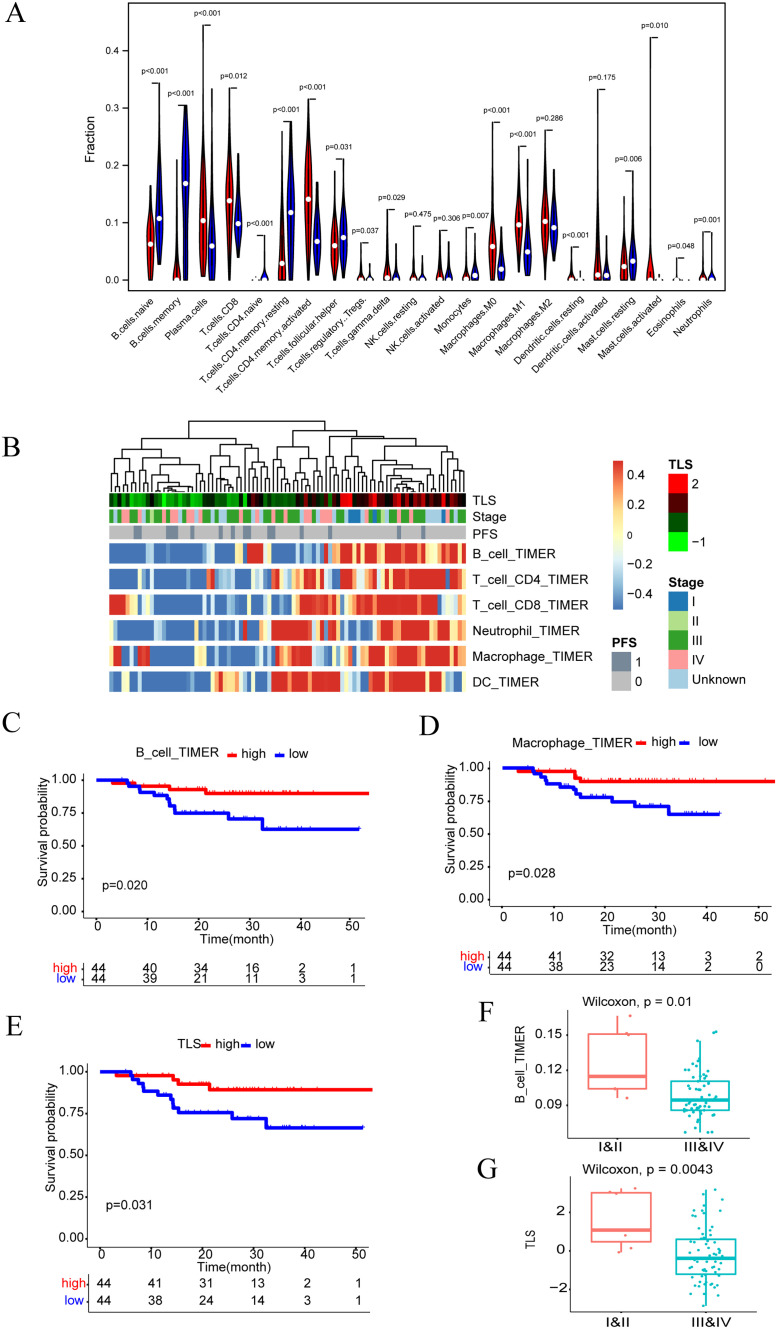

The analysis of immune cell infiltration in NPC

Notably, we estimated the composition of infiltrating immune cells by applying the CIBERSORT algorithm and found that the proportion of naïve B cells, menory B cells, naïve CD4+ T cells, resting memory CD4 T cells, Tfh cells, monocytes, and mast cells resting in normal tissues was higher than that of NPC samples (p < 0.05). By contrast, in NPC tissues, plasma cells, CD8+ T cells, activated CD4+ memory T cells, regulatory T cells, γδ T cells, M0 macrophages, M1 macrophages, resting dendritic cells, activated mast cells, and eosinophil neutrophils were generally higher than normal tissues (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). To further investigate the relationship between tumor-infiltrating B cells and NPC, we used the TIMER algorithm to perform immune cell infiltration analysis on the transcriptional sequencing data of 113 NPC cases (Fig. 3B). It was found that high levels of infiltration of B cells can significantly improve the prognosis of patients compared with low infiltration of B cells (Fig. 3C), and macrophages were also associated with a good prognosis of patients, while other cells such as CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, DC, and neutrophils were not associated with the prognosis of patients. (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. 1A–D). Previous research has shown that tumor-infiltrating B cells are closely associated with TLS, and our analysis also found that TLS was associated with good prognosis in NPC patients (Fig. 3E). In addition, B cells and TLS decreased with the progression of clinicopathological stage, while other cell subpopulations were not statistically significant (Fig. 3F and G and Supplementary Fig. 2A–E). Overall, our results demonstrate tumor-infiltrating B cells and TLS are associated with NPC patient survival and the clinicopathological stage, which suggests that B cells may play a crucial role in the NPC tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 3.

Results of immune infiltration analysis, survival analysis and correlation analysis. (A) The violin map showed the ratio of the differentiation rate of 22 kinds of immune cells from 95 NPC tumours and 40 normal tissues, and the significance was tested by Wilcoxon rank sum. (B) Heatmap showed the expression of 6 immune cell types in 88 NPC tumours with differential prognostic significance. (C) Kaplan–Meier curve of PFS (progression free survival) was adjusted according to the expression of B cells in the 88 NPC cohorts. (D) Kaplan–Meier curve of PFS according to the expression of Macrophage cells in the 88 NPC cohorts. (E) Kaplan–Meier curve of PFS according to the expression of TLS in the 88 NPC cohorts. (F) Correlation between B cells infiltration and clinical stage. (G) Correlation between TLS expression and clinical stage.

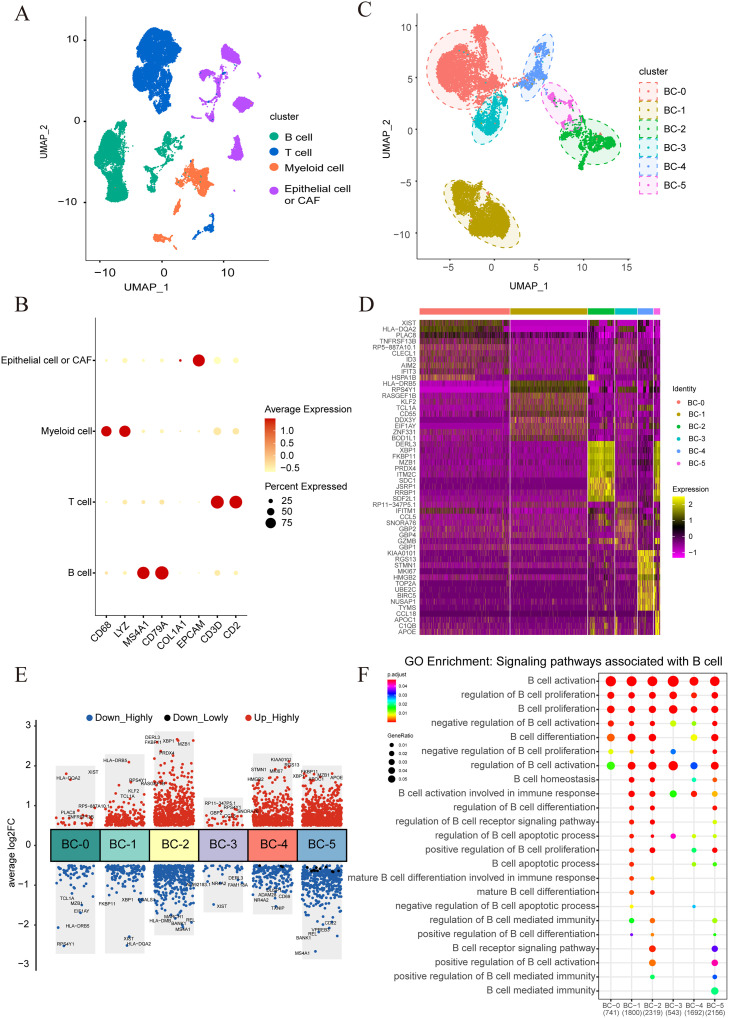

Single-cell sequencing analysis of NPC

We downloaded the single-cell transcriptome sequencing data of 15 NPC patients from GEO database to further explore the characteristics of the immune microenvironment of NPC and analyze the heterogeneity and the landscape of tumor-infiltrating B cells.The R package Seurat was used for quality control, dimensionality reduction, and cluster analysis. 46,001 cells could be classified into four major cell types based on typical cell marker genes, including the T cell population (marker genes: CD3D and CD2), B cell populations (marker genes: CD79A, CD79B, and MS4A1), myeloid cell populations (marker genes: CD14 and CD68), and tumor cells or fibroepithelial cell populations (marker genes: EPCAM and COL1A1) (Fig. 4A and B). Subsequently, we conducted further dimensionality reduction and cluster analysis on the B cell clusters, resulting in their classification into five distinct subtypes, including BC-0, BC-1, BC-2, BC-3, BC-4, and BC-5 (Fig. 4C). The BC-0 cell population has high expression of HLA-DQA2 and XIST genes; the BC-1 cell population has highly expressed HLA-DRB5 and KLF2 genes; the BC-2 cell population highly has expresses DERL3 and XBP1 genes; the BC-3 cell population has highly expressed CCL5 and IFITM1 genes; MKI67 and TOP2A genes were found to be highly expressed in the BC-4 cell population, while CCL18 and APOC1 genes were found to be highly has expressed in the BC-5 cell population (Fig. 4D and E). GO functional enrichment analysis found that each B cell subset was enriched in B cell activation and proliferation signaling pathways (Fig. 4F). In general, different B cell subsets have different expression characteristics and functions, which indicates that each B cell subset may play different roles in the tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 4.

Single cell sequencing analysis results of 15 cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. (A) The UMAP plot showed 46,001 single cells grouped into 4 major cell types, including T cells, B cells, Myeloid cells and malignant cells or fiber cells. (B) The Dot plot showed marker gene expression in 4 major cell types. (C) The UMAP plot showed B cells grouped into 6 B cell subtypes, including BC-0 cluster, BC-1 cluster, BC-2 cluster, BC-3 cluster, BC-4 cluster and BC-5 cluster. (D) A Heatmap showed expression of the top-10 most differentially expressed genes in 6 B cell subtypes. (E) A Dot plot showed differentially expressed genes in 6 B cell subtypes. The top-5 up-regulated or down-regulated genes were shown. (F) The GO enrichment analysis plot for B cell clusters in tumours depicts the signaling pathways associated with B cells.

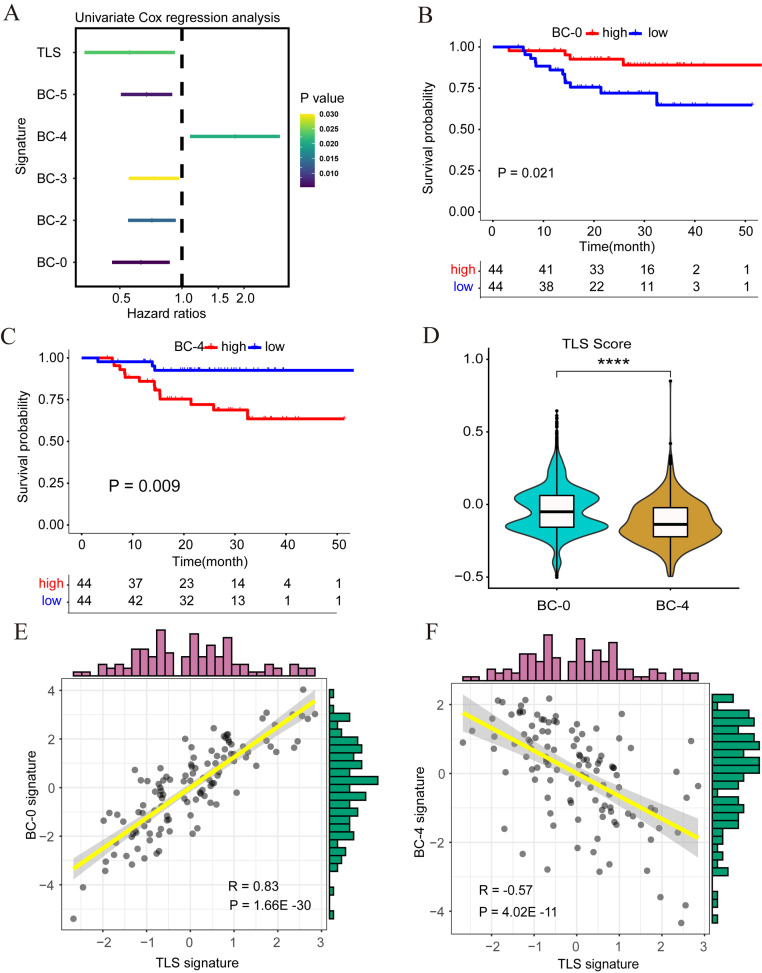

Association between B cell subsets and TLS

Our study found that both B cells and TLS were associated with good prognosis in NPC patients, but the relationship between B cells and TLS is currently unclear. Through univariate COX regression analysis, we found that BC-0, BC-2, BC-3, and BC-5 cell populations and TLS were independent predictors of a good prognosis in NPC patients, while the BC-4 cell population was a risk factor for a poor prognosis (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the BC-0 cell population was associated with a good prognosis of NPC (Fig. 5B), the BC-4 cell subpopulation was correlated with a poor prognosis of NPC (Fig. 5C), and the remaining B cell subpopulations were not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 3A–D). It was worth noting that the TLS gene set scores of the BC-0 cell population were higher than those of the BC-4 cell population (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5D). Further, correlation analysis indicated that the BC-0 cell population was positively correlated with TLS (Fig. 5E), while the BC-4 cell population was negatively correlated with TLS (Fig. 5F). These results showed that the BC-0 cell population may promote the formation of TLS and exert a potential anti-tumor effect, while BC-4 may promote tumor progression in NPC.

Fig. 5.

The relationship between B cell subsets and clinical prognosis and tertiary lymphoid structure. (A) Analysis of B cell subtypes and TLS using univariate COX regression. The significant critical factors were listed. (B) The Kaplan–Meier curve of PFS according to the expression of the BC-0 signature in the 88 NPC cohorts. (C) The Kaplan–Meier curve of PFS according to the expression of the BC-4 signature in the 88 NPC cohorts. (D) The violin plot showed a correlation between the TLS signature and the B cell cluster. (E) The scatter plot showed a correlation between the TLS signature and the BC-0 signature. (F) The scatter plot showed a correlation between the TLS signature and the BC-4 signature. **** p < 0.0001.

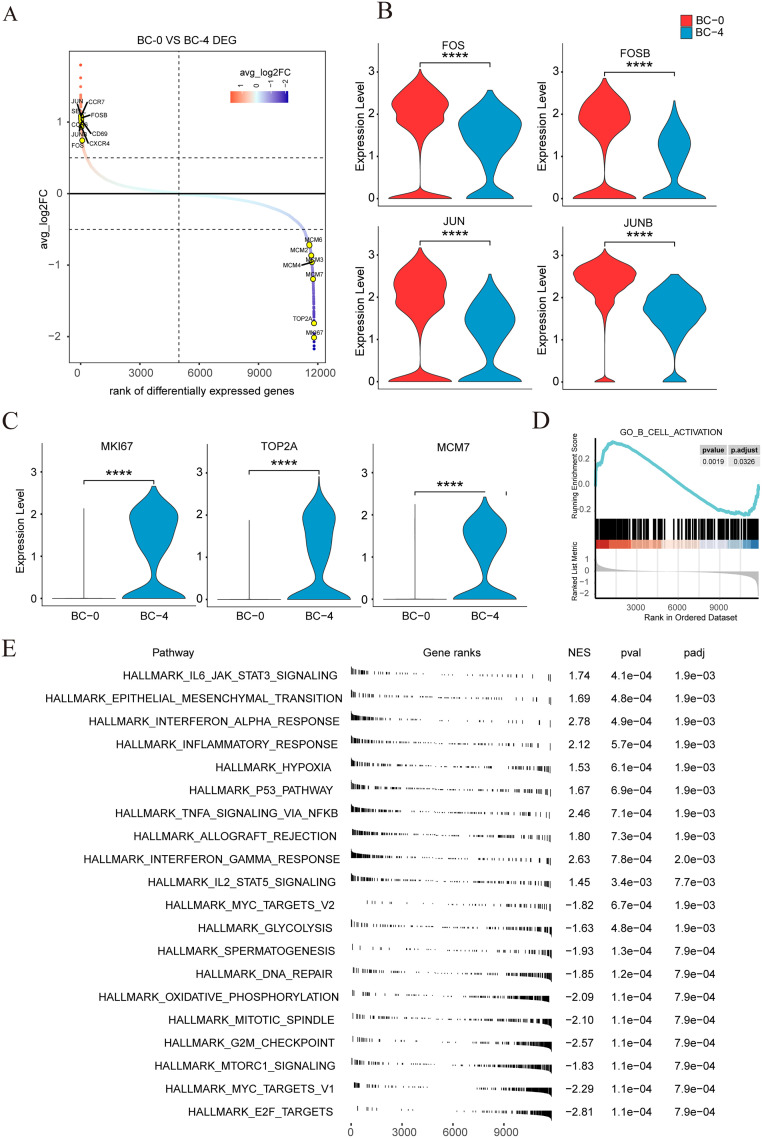

Diversity and characteristic of B cell subtypes in NPC

To further analyze the gene expression characteristics and pathway enrichment of the BC-0 cell population and the BC-4 cell population, we performed differential gene analysis on the two cell populations. The BC-0 cell population showed higher levels of key transcription factors, including JUN, JUNB, FOS, and FOSB (Fig. 6A), while the BC-4 cell cluster expressed high levels of proliferation-related genes, such as MKI67, TOP2A, and MCM7 (Fig. 6B and C). It is particularly interesting, that compared to the BC-4 cluster, genes in the pathway related to the B cell activation of the BC-0 cell population are up-regulated by using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Fig. 6D). The BC-0 cell population is mainly enriched in the IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway, hypoxia-related signaling pathway, IL2-STAT5 signaling pathway, etc., while the BC-4 cell population is mainly enriched in DNA repair, glycolysis, and other proliferation-related signaling pathways (Fig. 6E). Our results showed that the BC-0 cell population was in a significantly activated state. This cluster also expressed high levels of key genes such as JUN, JUNB, FOS, and FOSB, which played a key role in the immune microenvironment of NPC and may be a potential clinical target for immunotherapy.

Fig. 6.

Difference analysis and GSEA enrichment analysis results of BC-0 and BC-4 cell clusters. (A) Ranking of differentially expressed genes in the BC-0 cluster compared with the BC-4 cluster. Significantly differentially expressed genes of interest are labeled. (B) The violin plot showed the expression of 4 hub transcription factors (FOS, FOSB, JUN and JUNB) in the BC-0 and BC-4 cluster. (C) The violin plot showed the expression of 3 genes related to proliferation (TOP2A, MKI67 and MCM7) in BC-0 and BC-4 cluster. (D) The GSEA analysis plot showed the pathway of B cell activation was enriched in the BC-0 cluster. (E) The GSEA hallmark pathways are enriched in the BC-0 and BC-4 cluster, ordered by NES. **** p < 0.0001.

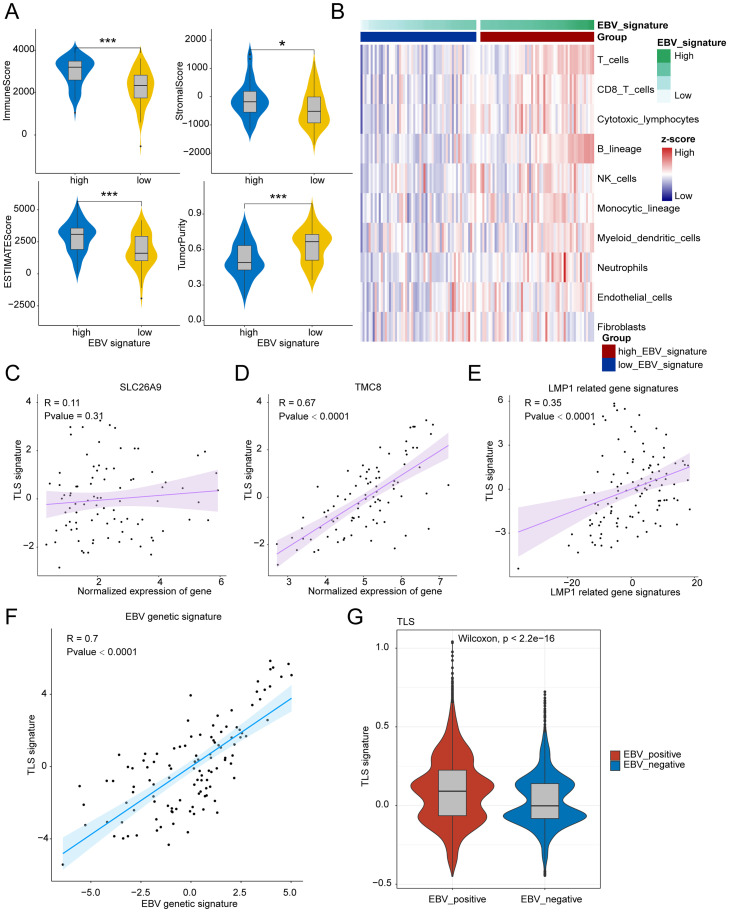

EBV infection associated with the formation of TLS

As shown in Fig. 7A, EBV genetic signature (Supplementary Table 1) high group show that high levels of immune score, stromal score and Estimate score and low levels of tumor purity. The stromal score, immune score, and ESTIMATE score represented the infiltration of stromal/immune cells, indicating that EBV infection was associated with the infiltration of immune cells and inflammatory tumor environment. Moreover, Immune infiltration analysis showed that EBV genetic signature high subtypes had high immune microenvironment infiltration, and EBV genetic signature low subtypes had the lowest immune microenvironment infiltration (Fig. 7B). This result is consistent with the literature that reports EBV positive NPC contains significantly more CD3, CD4, CD8 TILs than EBV negative NPC [26]. As we known, tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) contain B cells and T cells, associated with immune “hot” tumors. Above data suggested us that EBV infection was related with TLS expression. To further explore the role of EBV infection in shaping the tumor immune microenvironment, we firstly analysis the correlation between the expression of genes specific for EBV infected cells and TLS signature, the results showed that the expression of genes specific for EBV infected cells (SLC26A9 and TMC8) was positively associated with TLS signature (Fig. 7C and D). Additionally, latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) is the major transforming protein of EBV and correlation analysis showed that LMP1 related gene signature also significantly positive associated with TLS signature (Fig. 7E). Importantly, our analysis found that EBV genetic signature was significantly positive associated with TLS signature (R = 0.7, p<0.001, Fig. 7F), indicating that EBV infection was helpful for the formation of TLS and shaping the inflammatory tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, we compared the TLS expression between EBV-positive and EBV-negative NPC patients and found that there was higher level of TLS in EBV-positive patients (Fig. 7G). Some studies have found that EBV-positive npc have better prognosis as compared with EBV-negative cases [27,28] and that maybe in part because of better response to therapy for high TLS expression. In conclusion, our data suggested that EBV infection was important for the formation of TLS and heavy infiltration of immune cells around and within tumor lesions.

Fig. 7.

EBV infection was associated with the formation of TLS. (A) The violin plots show the ImmuneScore, StromaScore, ESTIMATEScore and Tumorpurity between High EBV genetic signature and Low EBV genetic signature. (B)The heatmap shows the relationship between EBV signature and the infiltration of immune cells in NPC. (C-F) The dot plot shows the correlation between the expression of SLC26A9 (C), TMC8 (D), LMP1 related genes (E) as well as EBV genetic signature (F) and TLS signature score. (G) The violin plot shows the TLS signature score between EBV positive and EBV negative patients with NPC. * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

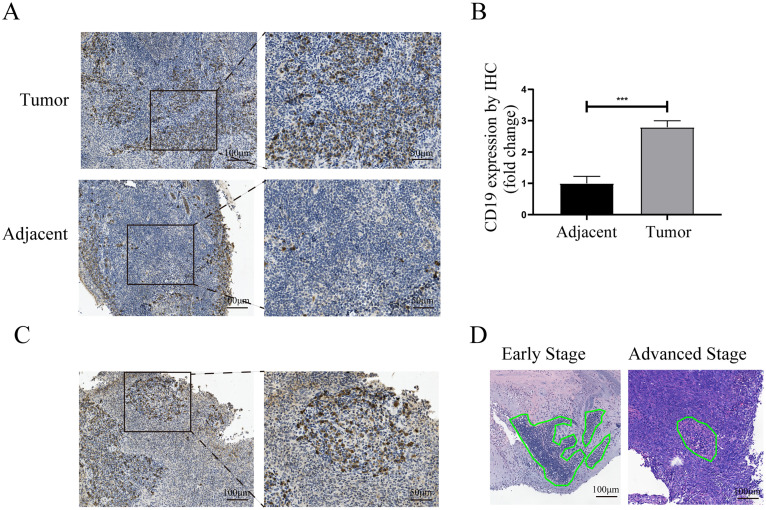

The infiltration of B cells and TLS in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and adjacent normal nasopharyngeal tissue

To further investigate the infiltration of B cell in NPC, IHC experiments were performed to examine the expression of B cells marker CD19 in NPC and adjacent tissues. Notably, the infiltration of B cells in NPC tissues was significantly higher than that in adjacent tissues (Fig. 8A and B). Consistent with the observation in the previous study [10], we also confirmed the presence of TLS in TME (Fig. 8C). As we found in RNA-seq analysis, HE staining showed that the density of TLS in the early stage of NPC was higher than that in advanced stage (Fig. 8D). Overall, our data suggested a potential relationship between the percentage of TLS and the anti-tumor function of infiltrating B cells.

Fig. 8.

The infiltration of B cells in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and adjacent normal nasopharyngeal tissue. (A) IHC staining of CD19 antibodies shows the infiltration of B cells in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues and adjacent normal tissues, bars, 100 μm. (B) The bar plot shows the difference in B cell infiltration between nasopharyngeal carcinoma and adjacent normal nasopharyngeal tissue. (C) TLS immunohistochemistry staining in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, scale bars, 100 μm. (D) The representative HE staining of TLS in early-stage and advanced-stage NPC, scale bars, 100 μm. *** represent p < 0.001.

Discussion

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated malignant tumor and is endemic in Southeast China and Asia [29]. Advanced NPC has a high risk of mortality due to disease recurrence or distant metastasis [30]. To date, previous studies have found several biomarkers that have been proven to be associated with prognosis in NPC, including genes, tumor immune subtypes, and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), such as CD3+ TILs and CD8+ T cells [31,32]. In this study, we identify differentially expressed immune-related genes associated with prognosis in RNA-seq and microarray data. GO and KEGG analyses showed the enrichment of B cell-related signaling pathways such as humoral immune response and B cell receptor-related pathways, which suggests that tumor-infiltrating B cells may have a close relationship with NPC.

The tumor immune microenvironment is closely related to the occurrence and development of tumor, which is the potential therapeutic target in cancer [33]. Previous studies have proved that infiltration of B cells is correlated with the prognosis of solid tumors such as high-grade serous ovarian cancer, skin cutaneous melanoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma [34], [35], [36]. Furthermore, infiltrating B cells were a favorable prognostic factor for patients with right-sided colon tumors but not for those with left‐sided or rectal tumors, indicating the broad complexity of the prognostic significance of infiltrating B cells [12]. However, the prognosis of infiltrating B cells in NPC is still not very clear. In this study, we found that high expression of B cell marker genes CD19 or CD79B was associated with improved prognosis in 88 NPC patients. We further calculated the signature score of infiltrating B cells using the TIMER algorithm and revealed its predicted values of prognosis in NPC. It was worth noting that infiltrating B cells were reported to be associated with a poor prognosis in melanoma [37], indicating the pro-tumor function of B cells. Assuredly, because of producing multiple pro-angiogenic factors [38] or the percentage of regulatory B (Breg) [39], infiltrating B cells can undoubtedly play a pro-tumor role. Here, we identified a B cell subpopulation BC-4 cluster that highly expressed proliferation genes MKI67, TOP2A, and MCM7, which were associated with poor outcomes in NPC patients, and a B cell subpopulation BC-0 cluster that highly expressed activated genes FOS, FOSB, JUN, and JUNB, which were associated with a better prognosis in NPC patients. Furthermore, our analysis revealed that B cell activation pathways were enriched in the BC-0 cluster, suggesting that activated B cells exert anti-tumor function.

Recent studies have shown that TLS is not only a predictive biomarker of immunotherapy response but also largely predicts a favorable prognosis in solid tumors [9], [10], [11]. Consistent with the previous studies, we further revealed that the signature of the TLS was associated with a better outcome in 88 NPC patients. In particular, the signature of the TLS declined along with the progression of clinical stage. Importantly, we demonstrated the presence of TLS in NPC by IHC staining of our collected samples, and the density of B cells in NPC was significantly higher than that of adjacent tissue. Indeed, emerging studies demonstrate that TLS are critical for anti-tumor responses, as it sustain B cell maturation, antibody production, as well as the recruitment and activation of lymphocytes [40,41]. Similarly, we found that the signature of the activated B cell subpopulation BC-0 cluster was positively associated with the TLS signature in NPC. Notably, the signature of the BC-4 cluster was negatively related to the TLS signature, indicating that not all B cell subpopulations contributed to the formation of TLS. Under the TME, crosstalk between infiltrating immune cells and stroma cells is extensive and dynamic and that together they regulate tumor immunity. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) play a significant role in the tumor microenvironment by engaging in cellular communication with other tumor cells and contributing to the secretion of extracellular matrix components [42,43]. Shimrit Mayer et al. found that the network of cell interactions in TME was hierarchical with CAFs at the top [44]. CAFs could enhance the recruitment of B cells through the secretion of CXCL13 [45]. One study found that endothelial cells can regulate immune responses and recruitment immune cells [46]. There are few studies reported CAFs-B cells and endothelial cells-B cells interactions and the mechanism is not yet clear. To further explore the crosstalk between B cells and CAFs and endothelial cells, we perform predict the ligand-receptor interactions between B cells and CAFs and endothelial cells in NPC and ESCC using CellChat software. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4A, there was obvious cell-cell communication between B cells and CAFs in NPC. B cells mainly crosstalk with CAFs through MIF-ACKR3 and LGALS9-CD44 ligand-receptor signaling and CAFs mainly crosstalk with B cells through MIF-(CD74+CXCR4) and MIF-(CD74+CD44), suggesting the MIF signaling play an important role in the crosstalk between B cells and CAFs (Supplementary Fig. 4B and C). Furthermore, we saw similar results when analysis another single cell RNA sequencing data (GSE196756, ESCC). CAFs and endothelial cells mainly crosstalk with B cells through MIF-(CD74+CXCR4) and MIF-(CD74+CD44) (Supplementary Fig. 5). Above data have determined that there was cell communication between B cells and CAFs and endothelial cells in tumor microenvironment and MIF signaling was the main signaling pathways for cell communications. Like our findings, some studies have reported that MIF promote B cells chemotaxis and proliferation [47], [48], [49]. In conclusion, our data indicated that CAFs or endothelial cells may communicate with B cells through MIF signaling to orchestrate B-cell clustering and helpful for the formation of TLS.

Recent investigations have elucidated the critical role of tumor-infiltrating B cells in orchestrating tumor-specific immunity, as evidenced by findings reported in the literature [40,50]. The work of Jiawei Lv and colleagues has shed light on the significance of B cell-mediated antitumor responses, pinpointing a particular B cell subset, termed ILB, as a promising biomarker for predicting the efficacy of gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy in NPC [51]. An intriguing study recently published in Nature has revealed that therapeutic targeting of the B cell-specific checkpoint TIM-1 can bolster anti-tumor immunity and curtail tumor proliferation [52]. Furthermore, outcomes from a phase III clinical trial have substantiated the notion that T cell immune checkpoint blockade markedly enhances the survival of patients with advanced NPC [53]. The synergistic application of B cell and T cell immune checkpoint inhibitors may herald a new frontier in NPC treatment modalities. Additionally, within the B cell milieu, Breg cells, which typically foster tumor progression, have emerged as potential targets. Attenuating Breg cell activity presents a novel and promising strategy in the NPC therapeutic arsenal. Continued investigation into B cell-related targets is poised to unlock novel avenues for NPC treatment.

In this study, we found that TLS is present in NPC and positively associated with the activated B cell subpopulation. Moreover, we investigated the transcription characteristics of an activated B cell subpopulation by bioinformatics analysis to determine infiltrating B cells and TLS as the prognostic biomarkers in NPC. Further investigation should be conducted to clarify the anti-tumor mechanism of infiltrating B cells and TLS.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Project (Clinical Pharmacy) and High Level Clinical Key Specialty (Clinical Pharmacy) in Guangdong Province. In addition, the study was also supported by funding of Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, grant number: (2021A1515011003).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chujun Chen: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Yan Zhang: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Xiaoting Wu: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Juan Shen: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of data repositories and funding agencies that provided the datasets and resources used in this study. We also thank the individuals who provided the human samples used in this research. This work was supported by various funding sources, for which we gratefully acknowledge.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2024.101885.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Cohen J.I., Fauci A.S., Varmus H., et al. Epstein-Barr virus: an important vaccine target for cancer prevention. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3(107):107fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gourzones C., Barjon C., Busson P. Host-tumor interactions in nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2012;22(2):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao Y.P., Xie F.Y., Liu L.Z., et al. Re-evaluation of 6th edition of AJCC staging system for nasopharyngeal carcinoma and proposed improvement based on magnetic resonance imaging. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009;73(5):1326–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L., Hu C.S., Chen X.Z., et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Economopoulou P., Kotsantis I., Psyrri A. The promise of immunotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: combinatorial immunotherapy approaches. ESMo Open. 2016;1(6) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitt J.M., Marabelle A., Eggermont A., et al. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2016;27(8):1482–1492. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y.Q., Chen L., Mao Y.P., et al. Prognostic value of immune score in nasopharyngeal carcinoma using digital pathology. J. ImmunOther Cancer. 2020;8(2) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinker G.S., Vitiello G.A.F., Ferreira W.A.S., et al. B cell orchestration of anti-tumor immune responses: a matter of cell localization and communication. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.678127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrita R., Lauss M., Sanna A., et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature. 2020;577(7791):561–565. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1914-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmink B.A., Reddy S.M., Gao J., et al. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature. 2020;577(7791):549–555. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1922-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petitprez F., de Reyniès A., Keung E.Z., et al. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature. 2020;577(7791):556–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1906-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berntsson J., Svensson M.C., Leandersson K., et al. The clinical impact of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancer differs by anatomical subsite: a cohort study. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;141(8):1654–1666. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shalapour S., Font-Burgada J., Di Caro G., et al. Immunosuppressive plasma cells impede T-cell-dependent immunogenic chemotherapy. Nature. 2015;521(7550):94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature14395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roghanian A., Fraser C., Kleyman M., et al. B cells promote pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(3):230–232. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-16-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fridman W.H., Meylan M., Petitprez F., et al. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures as determinants of tumour immune contexture and clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00619-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharya S., Dunn P., Thomas C.G., et al. ImmPort, toward repurposing of open access immunological assay data for translational and clinical research. Sci. Data. 2018;5 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leek J.T., Johnson W.E., Parker H.S., et al. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(6):882–883. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucl. Acid. Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuart T., Butler A., Hoffman P., et al. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell. 2019;177(7):1888. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. -902.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin S., Guerrero-Juarez C.F., Zhang L., et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1088. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu T., Hu E., Xu S., et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. (N. Y.) 2021;2(3) doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korotkevich G., Sukhov V., Budin N., et al. Fast gene set enrichment analysis. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/060012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman A.M., Liu C.L., Green M.R., et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Method. 2015;12(5):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng D., Ye Z., Shen R., et al. IOBR: multi-omics immuno-oncology biological research to decode tumor microenvironment and signatures. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.687975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wickham H. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics For Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ooft M.L., van Ipenburg J.A., Braunius W.W., et al. Prognostic role of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in EBV positive and EBV negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2017;71:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kijima T., Kinukawa N., Gooding W.E., et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with tumor cell proliferation: clinical implication in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2001;18(3):479–485. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yip K.W., Shi W., Pintilie M., et al. Prognostic significance of the Epstein-Barr virus, p53, Bcl-2, and survivin in nasopharyngeal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12(19):5726–5732. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-06-0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong K.C.W., Hui E.P., Lo K.W., et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an evolving paradigm. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021;18(11):679–695. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00524-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y.P., Chan A.T.C., Le Q.T., et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Rajhi N., Soudy H., Ahmed S.A., et al. CD3+T-lymphocyte infiltration is an independent prognostic factor for advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. BMC. Cancer. 2020;20(1):240. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06757-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y.P., Lv J.W., Mao Y.P., et al. Unraveling tumour microenvironment heterogeneity in nasopharyngeal carcinoma identifies biologically distinct immune subtypes predicting prognosis and immunotherapy responses. Mol. Cancer. 2021;20(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01292-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao Y., Yu D. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;221 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montfort A., Pearce O., Maniati E., et al. A strong B-cell response is part of the immune landscape in human high-grade serous ovarian metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23(1):250–262. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selitsky S.R., Mose L.E., Smith C.C., et al. Prognostic value of B cells in cutaneous melanoma. Genome Med. 2019;11(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0647-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi J.Y., Gao Q., Wang Z.C., et al. Margin-infiltrating CD20(+) B cells display an atypical memory phenotype and correlate with favorable prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19(21):5994–6005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Rodriguez M., Thompson A.K., Monteagudo C. A significant percentage of CD20-positive TILs correlates with poor prognosis in patients with primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 2014;65(5):726–728. doi: 10.1111/his.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang C., Lee H., Pal S., et al. B cells promote tumor progression via STAT3 regulated-angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosser E.C., Mauri C. Regulatory B cells: origin, phenotype, and function. Immunity. 2015;42(4):607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meylan M., Petitprez F., Becht E., et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures generate and propagate anti-tumor antibody-producing plasma cells in renal cell cancer. Immunity. 2022;55(3):527. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.02.001. -41.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo F.F., Cui J.W. The Role of Tumor-Infiltrating B Cells in Tumor Immunity. J. Oncol. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/2592419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilmi M., Nicolle R., Bousquet C., et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: accomplices in the tumor immune evasion. Cancer. (Basel) 2020;12(10) doi: 10.3390/cancers12102969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mao X., Xu J., Wang W., et al. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer. 2021;20(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayer S., Milo T., Isaacson A., et al. The tumor microenvironment shows a hierarchy of cell-cell interactions dominated by fibroblasts. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1):5810. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41518-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harper J., Sainson R.C. Regulation of the anti-tumour immune response by cancer-associated fibroblasts. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2014;25:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knolle P.A. Cognate interaction between endothelial cells and T cells. Result. Probl. Cell Differ. 2006;43:151–173. doi: 10.1007/400_018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klasen C., Ohl K., Sternkopf M., et al. MIF promotes B cell chemotaxis through the receptors CXCR4 and CD74 and ZAP-70 signaling. J. Immunol. 2014;192(11):5273–5284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klasen C., Ziehm T., Huber M., et al. LPS-mediated cell surface expression of CD74 promotes the proliferation of B cells in response to MIF. Cell Signal. 2018;46:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen S., Shoshana O.Y., Zelman-Toister E., et al. The cytokine midkine and its receptor RPTPζ regulate B cell survival in a pathway induced by CD74. J. Immunol. 2012;188(1):259–269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laumont C.M., Banville A.C., Gilardi M., et al. Tumour-infiltrating B cells: immunological mechanisms, clinical impact and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2022;22(7):414–430. doi: 10.1038/s41568-022-00466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lv J., Wei Y., Yin J.H., et al. The tumor immune microenvironment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma after gemcitabine plus cisplatin treatment. Nat. Med. 2023;29(6):1424–1436. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bod L., Kye Y.C., Shi J., et al. B-cell-specific checkpoint molecules that regulate anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2023;619(7969):348–356. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06231-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mai H.Q., Chen Q.Y., Chen D., et al. Toripalimab plus chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: the JUPITER-02 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(20):1961–1970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.20181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dodd L.E., Sengupta S., Chen I.H., et al. Genes involved in DNA repair and nitrosamine metabolism and those located on chromosome 14q32 are dysregulated in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(11):2216–2225. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-06-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bose S., Yap L.F., Fung M., et al. The ATM tumour suppressor gene is down-regulated in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Pathol. 2009;217(3):345–352. doi: 10.1002/path.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bao Y.N., Cao X., Luo D.H., et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor signaling is critical in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell growth and metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(12):1958–1969. doi: 10.4161/cc.28921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fan C., Wang J., Tang Y., et al. Upregulation of long non-coding RNA LOC284454 may serve as a new serum diagnostic biomarker for head and neck cancers. BMC. Cancer. 2020;20(1):917. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07408-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bo H., Gong Z., Zhang W., et al. Upregulated long non-coding RNA AFAP1-AS1 expression is associated with progression and poor prognosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(24):20404–20418. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang L., MacIsaac K.D., Zhou T., et al. Genomic Analysis of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Reveals TME-Based Subtypes. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017;15(12):1722–1732. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.Mcr-17-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deng Q., Han G., Puebla-Osorio N., et al. Characteristics of anti-CD19 CAR T cell infusion products associated with efficacy and toxicity in patients with large B cell lymphomas. Nat. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1061-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.