Abstract

Purpose

This review aimed to explore and synthesize the perspectives and experiences of school-based psychological professionals providing support to gender diverse CYP across the world, to foreground the voices of those with relevant experience and support future practice.

Methods

A systematic review of five databases (PsychINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, SCOPUS and PROQUEST dissertations and theses) was performed between September and November 2022. Articles were included if they contained qualitative, primary research data representing the voice of at least one school-based psychological professional with experience working with gender diverse children and young people. Articles were excluded if they did not contain primary research data, were quantitative, related to non-school based psychologists or focussed on participant views in the absence of direct experience working with gender diverse pupils. Articles were thematically summarized and organized into a data extraction table.

Results

Eighteen studies were identified for review, including 11 studies based in the USA, five in the UK, one in Australia and one in Cyprus. The voices of school-based professionals, including school counselors, school psychologists, trainee and qualified educational psychologists, were represented. The themes created highlighted the importance of the environment in which psychologists were working, the reliance on their own views and values to guide their work in the absence of clear guidance, the role psychologists saw they had to advocate for gender diverse CYP, as well as barriers and systems they were fighting against.

Conclusion

The review highlighted the need for psychologists to advocate for gender diverse children and young people, in an often non-inclusive environment where there was a need to work systemically with schools. Future research is needed to explore young people’s experiences of the support that they are receiving and would like to receive.

Keywords: Heteronormativity, identity, LGBTQ+, psychologists, school-based

Introduction

Gender identity has been defined as a person’s internalized sense of their gender (American Psychological Association [APA], 2023) and where this aligns with their sex assigned at birth, individuals are commonly referred to as “cisgender” (Connolly et al., 2016). For this research, gender diversity will be used as an umbrella term to refer to those whose gender identity diverges from their sex assigned at birth. In line with Allen-Biddell and Bond (2022), this encapsulates a spectrum of identities, both within and outside of the traditional binary models of gender. Increasing numbers of children and young people (CYP) are identifying and expressing themselves in ways that do not correspond with their sex assigned at birth (Butler et al., 2018; Twist & de Graaf, 2019). Current estimates of gender diverse individuals are between 0.1 and 2% of the population, varying based on how and where studies were conducted (Goodman et al., 2019). Nonetheless, it is speculated that existing data may underestimate the prevalence of gender diversity (Spizzirri et al., 2021) and Sagzan (2019) acknowledges the difficulties of accurately estimating the prevalence of gender diverse CYP in schools. Although exact numbers are uncertain, research has shown that referrals for CYP to specialist gender identity services has significantly increased over the last decade (Butler et al., 2018; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2018; Steensma et al., 2013). It is worth noting however, that these statistics may not reflect an inherent increase in gender diversity, but rather an increased awareness or that CYP are open about their identities at a younger age (Leonard, 2019).

Despite debate regarding the prevalence of gender diverse CYP, research consistently reports poorer outcomes for these individuals compared to their cisgender peers. Gender diverse CYP are found to be at greater risk for mental health difficulties such as depression, self-harm, suicide, eating disorders and anxiety (Connolly et al., 2016; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2018; Nodin et al., 2015; Rivas-Koehl et al., 2022; Stonewall, 2017; Yunger et al., 2004). Additionally, compared to their cisgender peers, research highlights gender diverse CYP experience poorer academic functioning (Vantieghem & Van Houtte, 2020) and increased risks of engaging in harmful behaviors such as drinking alcohol, smoking, (Coulter et al., 2018) or taking illegal substances (Day et al., 2017).

Research highlighting disparities in mental health outcomes for gender diverse individuals risk situating the problem within gender diversity or the CYP themselves. On the contrary, negative outcomes are not inherent to gender diverse CYP and research has found that systemic factors need to be considered to further understand this relationship (Bryan & Mayock, 2017; Pyne, 2014). Indeed, gender diverse CYP face many risks within education systems and are frequently reported to be among the most oppressed and marginalized within school cultures (Kosciw & Pizmony-Levy, 2016) due to the prominence of cisnormativity throughout the school day (Bower-Brown et al., 2021). Additionally, research from across the world (e.g. United States, Australia, Canada, and United Kingdom), reports that gender diverse CYP experience higher rates of bullying, discrimination, and victimization within the school environment, compared to their cisgender peers (Day et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2016; Kosciw et al., 2015; Stonewall, 2017). Significant proportions of gender diverse CYP thus describe feeling unsafe in school (Stonewall, 2017; Kosciw & Pizmony-Levy, 2016) and often do not feel staff have adequate training, understanding or skills to counteract this (McGuire et al., 2010), at times being the perpetrators of discrimination themselves (Austin & Craig, 2015). These adverse experiences and interactions are posited to relate to the poorer outcomes reported for gender diverse CYP (Colvin et al., 2019; McBride & Schubotz, 2017; McDermott et al., 2018; Rivas-Koehl et al., 2022).

Although school environments are frequently portrayed as a risk factor for gender diverse pupils, several protective factors have also been identified. Research suggests that in schools where CYP feel valued, supported, and safe, all pupils, including those who are gender diverse, can flourish (Rivas-Koehl et al., 2022; Russell et al., 2014). In gender diverse populations, having positive relationships with key trusted adults in school has been associated with reduced rates of depression and suicide attempts (Rivas-Koehl et al., 2022), increased self-esteem (Dessel et al., 2017), improved academic functioning (Goodrich, 2012; Kosciw et al., 2018) and an increased sense of safety (McGuire et al., 2010). Further, peer support has been found to have beneficial influence for gender diverse CYP (Rivas-Koehl et al., 2022) alongside wider community visibility and support (Johns et al., 2018). The importance of supportive school policies has also been highlighted (Hong & Garbarino, 2012; Johns et al., 2018) and this is associated with reduced absence amongst gender diverse pupils (Greytak et al., 2013). Such policies, that promote the use of gender inclusive language and whole school approaches to advocacy, are deemed important protective factors by gender diverse CYP (Leonard, 2022). Beyond the school environment, parent and family support is also recognized as a key protective factor (Johns et al., 2018; Rivas-Koehl et al., 2022), and where this may not be in place, school support appears even more important (Kosciw et al., 2018).

Despite the potential protective role schools can offer, there is a lack of guidance to support them in this work. In the UK for example, there is currently no central policy for schools around supporting gender diverse pupils, and although local authorities have written their own guidance for schools, many have been withdrawn due to negative press or legal challenge. Similarly in the United States, individual cities and states have created guidelines or recommendations to support gender diverse pupils in schools, however state laws and guidelines vary widely and therefore subsequent support will also.

School-based psychological professionals are therefore ideally situated to support schools, staff, and families and promote positive outcomes for gender diverse CYP. In the UK for example, educational psychologists (EPs) utilize evidence-based practice to support educational settings at individual (child/family), group and organizational levels, in order to improve outcomes related to CYP’s wellbeing and learning (Fallon et al., 2010; Yavuz, 2016). Through their position, EPs can thus apply their understanding of school systems, psychology, and research to support schools work with gender diverse CYP (Leonard, 2019). Comparably, school psychologists (SPs) in the USA and Australia occupy a similar role in supporting CYP within academic, emotional, and behavioral areas, through work with individual CYP, families, school staff, and systems (Bartholomaeus & Riggs, 2017; Betts, 2013; Mackie et al., 2021). School counselors also provide individual support to gender diverse CYP and work within their school systems to enact change (Mackie et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, research highlights a mixed picture in terms of school-based psychologists’ attitudes, understanding and readiness to engage in this work. It is generally reported that school-based psychologists embrace positive attitudes toward gender diverse pupils and feel somewhat confident and prepared to work with these pupils (Arora et al., 2016; Bowers et al., 2015; Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2015), yet some studies have found feelings of very low competence to support gender diverse youth (Shi & Doud, 2017). Their confidence and readiness being influenced by the training they have received and previous experience (Arora et al., 2016; Bowers et al., 2015; Meier, 2019). Often it is the case that school-based psychologists have received little to no training specific to working with gender diverse CYP (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2015) and many report having not worked with any gender diverse pupils to date (Bowers et al., 2015). Given the increasing prevalence and visibility of gender diverse CYP (Butler et al., 2018; Twist & De Graaf, 2019), school-based psychologists are now more likely to be involved in such work (Ullman, 2017; Yavuz, 2016). The current review therefore aims to explore the experiences and perspectives of those who have engaged in this work, to better inform practice moving forwards.

Methodology

Aim

A systematic literature review was carried out to explore the question: what are the perspectives and experiences of school-based psychological professionals providing support to gender diverse CYP? The specific objective were to summarize the voices of school-based psychological professionals who have engaged in work with gender diverse CYP and to use any new insights to inform future practice in the current absence of any clear guidance.

Selection and search strategy

Using the Population Concept Context (PCC) framework, three key search terms were identified to answer the review question; “gender diverse,” “psychological professional” and “school” (see Table 1 for further information). The search terms were used in five electronic databases (PsychINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, SCOPUS and PROQUEST dissertations and theses), chosen due to their focus on education and Psychology, as well as to ensure grey literature was included. All database searches were carried out between September and November of 2022. Search terms were limited to title and abstracts and were modified for each database. Initial searches excluded books and were limited to those written in the English language and from 2010 onwards. Further research was identified through an online conference.

Table 1.

Search terms identified using PCC framework.

| PCC framework | Key terms | Search terms |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Gender diverse | "gender divers*" OR "gender varian*" OR transgender OR "gender identity disorder*" OR "gender identit*" OR "gender dysphori*" OR "two spirit" OR two-spirit OR "gender nonconform*" OR "gender non-conform*" OR "gender queer" OR genderqueer OR "gender non-binar*" OR "gender non binar*" OR "gender fluid*" OR agender OR non-gender OR bi-gender |

| Concept | Psychological professional | psychologist OR counsel* OR therap* |

| Context | School | school* OR educat* OR classroom |

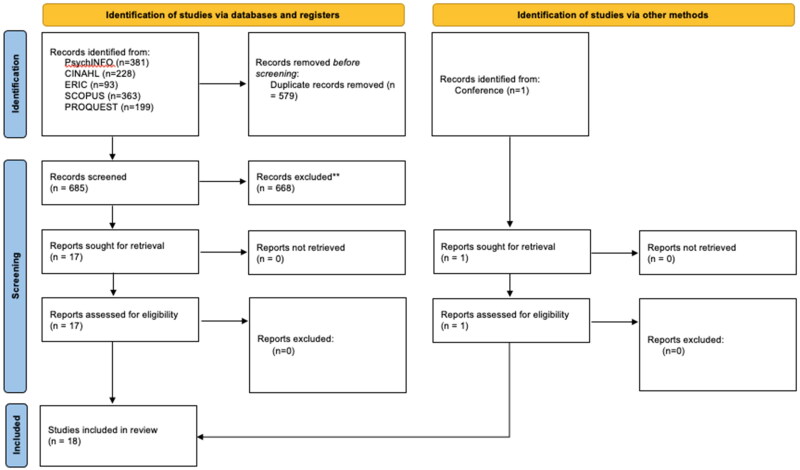

The systematic search strategy produced 1264 results. Following the PRISMA flowchart (Page et al., 2021; Figure 1), titles and abstracts of 685 papers were screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). To answer the research question, this review focussed on qualitative literature as we wanted to explore the nuances, experiences, and meanings in a way that quantitative studies would not. Eighteen articles were retrieved for full text screening, all of which were included in the final review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart (Page et al., 2021).

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

Quality assurance

All 18 articles were quality appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2018) qualitative studies checklist. The checklist requires a yes, no or can’t tell response to most questions and as such a scoring system is not applied. The focus of the quality appraisal was to explore the methodological rigor of studies and avoid drawing conclusions from papers with little rigor (Thomas & Harden, 2008).

Overall, the studies included had clear aims and utilized appropriate methodology and design in relation to their aims. Due to several theses being included in the review, there was a great deal of information available regarding methodology and findings which helped ascertain rigor. For some published papers where less information was available, it was harder to make judgements on rigor in areas. For example, in several papers it was unclear whether there was adequate consideration of the relationship between the researcher and participants or whether data analysis was sufficiently rigorous. See Table 3 for further information regarding how papers were quality assured.

Table 3.

Quality appraisal of studies using CASP (2018).

| Clear aims | Appropriate methodology | Appropriate design | Recruitment appropriate | Data collection | Participant-researcher relationship | Ethics considered | Data analysis | Findings clear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen-Biddell & Bond (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y |

| Apostolidou (2020) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | CT | CT | CT | CT |

| Beck (2018) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Beck (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Betts (2013) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y |

| Bowskill (2017) | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y |

| Court 2019) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Earnshaw et al. (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | CT | CT |

| Gavin (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Gonzalez (2016) | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Gonzalez (2017) | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Mackie et al. (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Reisner et al. (2020) | N | Y | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | CT | Y |

| Simons & Cuadrado (2019) | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | CT | CT | CT | Y |

| Sagzan (2019) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Swindle (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y |

| Vela (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y |

| Yannalfo (2019) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y |

*Y: Yes; N: No; CT: Can’t Tell.

Data extraction and synthesis

Thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008) was chosen as the process by which to analyze the 18 studies included in the review (see Table 4). The inductive approach suited the exploratory nature of the review question and allowed for interpretative analysis of existing literature (Boland et al., 2017; Thomas & Harden, 2008). This was pertinent to enable in-depth analysis of studies with differing aims to be brought together to answer the review question, whilst providing a novel perspective relevant to future practice (Drisko, 2020). The use of thematic synthesis aligns with a social constructivist epistemology, in which knowledge is seen to be formed through our interactions with people and the world around us, and how we make sense of these (Alanen, 2015). Thus, throughout this review, I had an active role in constructing new meaning through my interactions with the data and interpretations influenced by my own beliefs and experiences, acknowledging and welcoming my previous experiences as a trainee educational psychologist, as well as my own identity as part of the LGBTQ + community, throughout the review process.

Table 4.

Data extraction table.

| Author (year) | Country | Research question/s or aims | Participant characteristics and context | Data collection methods | Data analysis approach | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen-Biddell & Bond (2022) | UK | What are educational psychologists’ experiences and practices of working with autistic, gender-diverse children and young people? | Educational Psychologists with experience working with autistic, gender diverse CYP (n = 5) Participants focussed on direct casework involving gender diverse CYP. |

Semi-structured interviews (via Zoom) | Reflexive thematic analysis | Themes:

|

| Apostolidou (2020) | Cyprus | (a) explore professionals’ experiences regarding homophobic and transphobic bullying in schools, (b) investigate their views in relation to how these issues are being addressed by the school community and, (c) examine professionals’ views concerning the aspects they consider important for combating homophobic and transphobic bullying in school. | Group 1 (n = 4): teachers (3 secondary, 1 primary) Group 2 (n = 4): 2 school psychologists, 1 school counselor, 1 primary school teacher/clinical psychologist trainee Group 3 (n = 8): 4 parents and 4 school children. |

Focus groups, discussions led by interview protocol. Discussions focussed on professional’s views and experiences related specifically to homophobic and transphobic bullying. |

Thematic analysis | Themes:

|

| Beck (2018) | USA—Midwest and East Coast | What are the lived experiences of school counselor–principal teams who make concerted advocacy efforts for LGBT students? | School counselors (n = 5) Principals (n = 4) School counselor in training (n = 1) Participants must have been recognized at the national or state level for ensuring a safe and inclusive environment for LGBT students in their work. |

Three rounds of semi-structured interviews. | Moustaka’s (1994) approach to phenomenological reduction. | Themes:

|

| Beck (2020) | USA—Midwest and East Coast | How do exemplary school counselors and principals make meaning of their advocacy work with LGBT students? | Four ‘exemplary’ participants; principal (n = 2) School counselor (n = 2) Participants must have been recognized at the national or state level for their commitment to ensuring a safe and inclusive environment for LGBT students. |

3 rounds of semi-structured interviews. | Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach (Larkin & Thompson, 2012) | Themes:

|

| Betts (2013) | USA | 1. What do school psychologists know about LGBTQ issues and how do they deal with it in their practice? 2. How does a school psychologist evolve from tacitly knowledgeable to LGBTQ competent to LGBTQ advocacy? 3. What skills, traits, or life experiences are instrumental in shaping school psychologists in becoming a social change agent for LGBTQ youth? |

School psychologists (n = 8) Graduate professor of school psychology (n = 2) Participants were selected from previous survey data that highlighted those who were considered active advocates for LGBTQ social justice concerns. |

Semi-structured interviews | Constant comparison method (Merriam, 2009) | Themes:

|

| Bowskill (2017) | UK | To explore how educational professionals can ensure better outcomes for transgender children and young people. | Transgender adults (n = 15) professionals who have worked with transgender young people (3 = Educational Psychologist, 1 = clinical psychologist, 3 = teachers, 1 = TA, 2 = youth workers). |

Intensive interviewing Theoretical sampling—allowing each interview to feed into the next |

Grounded Theory was used. | Five interlinked categories:

|

| Court (2019) | Wales | 1. What constructs do EPs and TEPs within Wales hold in relation to GV? i. What level of experience do EPs and TEPs within Wales currently have in supporting CYP who express GV? ii. What role do EPs/TEPs within Wales perceive themselves holding in relation to GV? |

Trainee Educational Psychologists/Educational Psychologists (n = 7) | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis | Themes linked to RQ 1

Theme linked to secondary RQ i:

Themes linked to secondary RQ ii:

|

| Earnshaw et al. (2020) | USA—Massachusetts | To characterize and compare the perspectives of LGBTQ students and SHPs on: (1) experiences of LGBTQ bullying, and (2) SHP responses to LGBTQ bullying. | LGBTQ youth (n = 28) School health professionals (school nurse (n = 11), school psychologist (n = 3), guidance counselor (n = 1), social worker (n = 3), health education teacher (n = 1)) |

Online, asynchronous focus groups | Rapid Qualitative Inquiry (Beebe, 2014) | Summarized experiences of LGBTQ bullying and responses to LGBTQ bullying from perspectives of young people and SHPs. |

| Gavin (2021) | UK (South-East England) | What are their perceptions of: a. how they currently best support trans* young people? b. how they currently do not best support trans* young people? c. how to improve the support of trans* young people? |

Secondary school staff (n = 22) Educational Psychologists (n = 8) Key personnel working at national level (n = 2) |

Semi-structured interviews—individual interviews and focus group interviews conducted | Thematic analysis | Themes:

|

| Gonzalez (2016) | USA (South Eastern) | To investigate the experiences of school counselors who have served as advocates with and on behalf of LGBT students. Examine factors that facilitate and impede school counselors’ advocacy efforts with LGBT students. |

High school counselors (n = 12) Participants were required to have acted as advocates for and with LGBT students, including 10 having had involvement in the schools Gay Straight Alliance (GSA), 10 had engaged in advocacy work with community organizations and all had advocated for LGBT students on an individual basis. |

Semi structured interviews and document review | Constant comparative analysis | Two overarching thematic categories:

|

| Gonzalez (2017) | USA (South Eastern) | What are the lived experiences of high school counselors in the south- eastern U.S. who advocate for and with LGBT students? | High school counselors (n = 12) Participants must have served as advocates for and with LGBT students e.g. being involved in schools GSA. |

Semi structured interviews and document review | Constant comparative analysis. | Themes:

|

| Mackie et al. (2021) | Australia | To explore the experiences of school psychologists working with transgender young people in a school counseling context. | School psychologists (n = 7) | Semi-structured interviews (via Zoom) | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) − 6 steps outlined by Smith et al. (2009) | Themes:

|

| Reisner et al. (2020) | USA—Massachusetts | Sought to identify multilevel factors that inform interventions to increase SHPs’ capacity to report and respond to LGBTQ bullying. | LGBTQ youth (n = 28) School health professionals (n = 19, included 3 school psychologists) |

Online focus groups (3 with 28 youth, 2 with 19 SHPs)—online forum where participants could read and reply to questions and comments anytime during the day. | Rapid Qualitative Inquiry (Beebe, 2014) | Three overarching thematic categories describing barriers and facilitators to addressing LGBTQ student bullying—coalesced around the social ecological model:

|

| Sagzan (2019) | UK (outer London) | How do Educational Psychologists perceive their role in supporting schools to improve outcomes for trans* pupils? | Educational Psychologists (n = 8) | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Themes:

All grounded by a 6th theme:

|

| Simons & Cuadrado (2019) | USA—Midwest | What has LGBTQ school counselor advocacy looked like in schools and why has it occurred or not? | Counselors, who self-identified as “advocates,” employed by high schools (n = 9) | Semi-structured interviews. Drew upon theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 2015) to inform interview protocol. |

Coded data were restricted to the 4 TPB categories to allow calculation of the frequency and average occurrence of the narrative data. | Themes:

|

| Swindle (2022) | USA—Oregon | What are the experiences of Oregon secondary educators regarding supporting LGBTQ + students? | School counselors (n = 3) Teachers (n = 3) Administrator (n = 1) Participants must have interacted with LGBTQ + students in a school setting. |

Two rounds of semi-structured interviews and member checking. | Inductive analysis | Three general factors that influenced educators’ work with LGBTQ + students:

|

| Vela (2015) | USA—Southwestern (Texas) | What are the school counseling experiences of an LGBTQ high school student? What are the experiences of the school counselor while working with students of diverse sexual orientations? What are the experiences of parents of LGBTQ students with the school counselor? |

LGBTQ students (n = 4) Parents (n = 3) School counselors (n = 8) |

Individual semi-structured interviews (with 10 participants) Focus group with five school counselors |

In vivo coding methods | Themes:

|

| Yannalfo (2019) | USA—Midwestern | What are school support personnel’s perceptions of their work with transgender and gender diverse students in a Midwestern urban public school district? | Social worker (n = 1) Counselor (n = 3) School psychologist (n = 3) |

Semi-structured interviews | Thematic Analysis | Themes:

|

All text within the results or findings sections of each article was explored in the analysis, drawing from both direct participant quotations and authors’ interpretations of these. Only data that could answer the review question was coded. This meant data from study participants that were not school-based psychological professionals was not coded, nor data that exclusively referred to sexual identity as opposed to gender identity. Instances where this was not made explicitly clear were coded to ensure relevant data was not lost, for example participant characteristics were not identifiable in results or LGBTQ + identities were referred to more broadly.

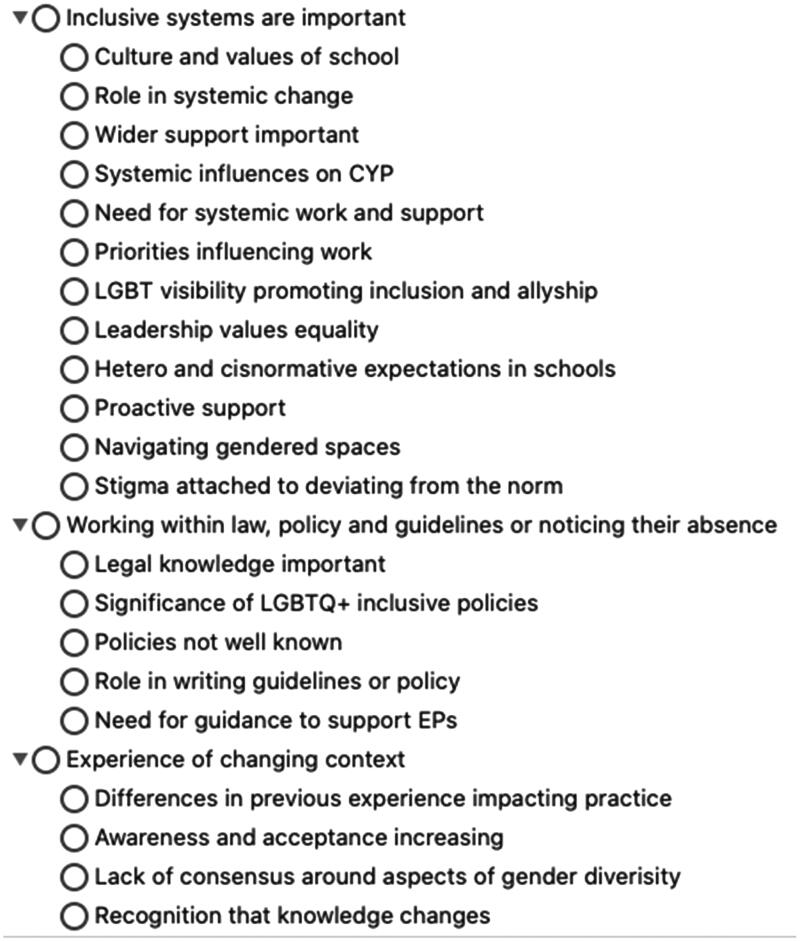

A thematic synthesis was conducted, with NVivo (release 1.7.1) software used to store and code the data. Analysis followed an iterative, three-step process, in line with Thomas and Harden’s (2008) approach. The first stage involved line-by-line coding whereby each sentence, line or comment was coded based on the content, with one or more “free” codes. Throughout this stage, codes were renamed and refined to begin the process of synthesizing concepts from one study to another. This process created 101 initial codes. The second stage involved the researcher grouping free codes based on similarities and differences, creating new codes to reflect these groups. This stage resulted in 16 descriptive themes. Figure 2 provides an example of codes that were used to create three of the descriptive themes. Table 5 illustrates the prevalence of descriptive themes within each article. The third stage involved moving beyond the primary studies’ data and generating additional understanding from their findings, a crucial aspect of thematic synthesis (Britten et al., 2002; Dixon-Woods et al., 2006). This involved drawing on the descriptive themes to generate new meaning that directly answered the research question.

Figure 2.

Thematic synthesis stage one to two. Example of descriptive themes developed from initial codes.

Table 5.

Descriptive themes identified in each of the reviewed studies.

| Descriptive themes: | Allen-Biddell & Bond (2022) | Apostolidou (2020) | Beck (2018) | Beck (2020) | Betts (2013) | Bowskill (2017) | Court (2019) | Earnshaw et al. (2020) | Gavin (2021) | Gonzalez (2016) | Gonzalez (2017) | Mackie et al. (2021) | Reisner et al. (2020) | Sagzan (2019) | Simons & Cuadrado (2019) | Swindle (2022) | Vela (2015) | Yannalfo (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive systems are important | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Working within law, policy, and guidelines or noticing their absence | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Experience of changing context | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Importance of own knowledge and awareness | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Importance of own personal attribute, views, and values | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Experience of their role as a psychologist | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Advocacy for and being a role model to | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Educating and challenging others | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Working collaboratively with stakeholders | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Empowering CYP | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Importance of individualized approach | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Promoting acceptance and belonging | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Barriers to effective support | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Experiences of conflict | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Experience of the impact of stigma and prejudice on their work | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Religious and political views | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N |

Synthesis

Synthesis overview

Eighteen studies were included in the review, published between 2013 and 2022. Of these 18 studies, 11 were based in the USA, five in the UK, one in Australia and one in Cyprus. The voices of 141 school-based psychological professionals were represented, including school counselors, school psychologists, trainee educational psychologists and educational psychologists. Table 4 provides an overview of participants role in schools and some activities in which they were involved where this was stated.

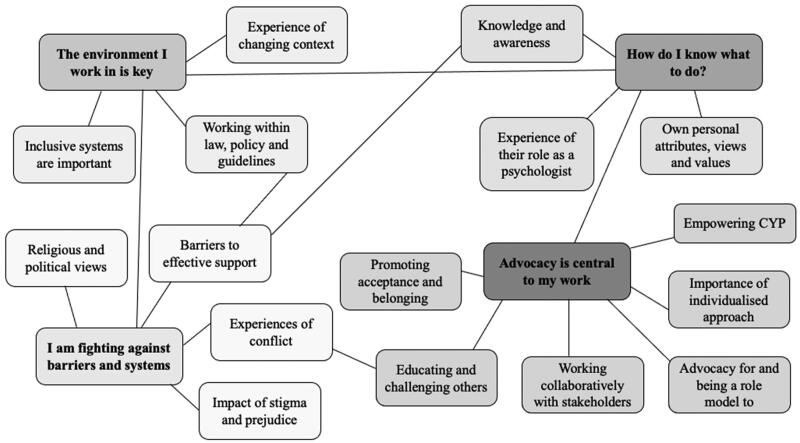

Four analytical themes were developed in answer to the research question “what are the perspectives and experiences of school-based psychological professionals providing support to gender diverse CYP?”: “The environment I work in is key,” “How do I know what to do?,” “Advocacy is central to my work,” and “I am fighting against systems and barriers.” These analytical themes, and related subthemes, are depicted in a thematic map (see Figure 3). Examples of where themes are represented are referenced throughout, with further details provided in Table 5.

Figure 3.

Thematic map depicting analytical and descriptive themes, as well as links between themes.

Analytical themes

The environment I work in is key

Psychologists in the reviewed research acknowledged that the environment in which they are working is key, yet often found themselves working within an ever-changing culture and context. From the perspective of psychologists, there is little consensus around the clinical, linguistic, and legal frameworks that might otherwise inform their practice (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Bowskill, 2017; Court, 2019; Sagzan, 2019); even where these are established, they fluctuate with rapidly changing knowledge and understanding (Sagzan, 2019; Vela, 2015). Acceptance of gender diversity was seen by psychologists to be expanding through student populations (Sagzan, 2019; Swindle, 2022; Vela, 2015), wider society (Sagzan, 2019; Vela, 2015), and even through their own profession (Sagzan, 2019), reflected in the surging need for intervention, with referrals for supporting transgender young people also increasing (Gavin, 2021). In this new world however, psychologists felt lost. Their diverse experiences have contributed to a broad spectrum of approaches to gender-diverse practice (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022). These approaches, in turn, have been met with varying levels of acceptance and openness to gender diversity (Vela, 2015). Consequently, psychologists considered this an “emerging area of practice” (Court, 2019).

In unfamiliar territory, psychologists nonetheless endorsed the importance of inclusive systems. These were described as systems that promoted positive and inclusive staff attitudes (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; González, 2016), where LGBTQ + visibility was seen throughout the environment and curriculum (Beck, 2018; Bowskill, 2017; Gonzalez, 2017), and wider support from administrative teams was embedded (Gonzalez, 2016). Psychologists perceived that inclusive school environments such as these allowed students and staff to feel safe, supported, and comfortable to be themselves (Reisner et al., 2020; Swindle, 2022) and gifted psychologists greater autonomy in their work and support of gender diverse CYP (Reisner et al., 2020; Swindle, 2022). Nevertheless, this was often not the reality psychologists experienced in their work (Reisner et al., 2020; Swindle, 2022), which instead reflected the prevalence of cisnormative expectations in schools (Apostolidou, 2020; Bowskill, 2017; Sagzan, 2019), with stigma attached to those who deviate from them (Apostolidou, 2020; Sagzan, 2019). The impact these systemic issues such as transphobia and prejudice of staff and peers, can have on CYP was recognized by psychologists (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022). Together, this created a desire to advocate for systemic work, with change needed “on many levels” (Beck, 2018; Betts, 2013; Bowskill, 2017; González, 2016).

Psychologists therefore perceived they had a role to play in supporting a shift toward more inclusive school cultures (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Gonzalez, 2016). “Learning about the school’s values” (Beck, 2020) and the values held by key leadership figures (Gonzalez, 2016; Sagzan, 2019; Swindle, 2022) were helpful starting points for psychologists. Going beyond awareness and actively promoting an inclusive ethos and environment through transparency around their commitment to diversity, and their acceptance and support of gender diversity (Beck, 2018, 2020; Gonzalez, 2017; Yannalfo, 2019), was also deemed important.

Beyond the immediate environment within which they were working, psychologists reflected upon their experiences of working within wider laws, policies, and guidelines. The significance of having policies focussed on inclusive LGBTQ + practices was highlighted by psychologists and fostered greater confidence and scope to advocate for and support gender diverse pupils (Gonzalez, 2016). This confidence, however, relied on such policies existing and psychologists having up to date knowledge around the legalities of practice (Gonzalez, 2017; González, 2016; Simons & Cuadrado, 2019; Yannalfo, 2019), often not a reality experienced (Sagzan, 2019; Swindle, 2022; Yannalfo, 2019), yet psychologists often found themselves developing policies within schools and local areas (Mackie et al., 2021; Sagzan, 2019; Swindle, 2022). Moreover, psychologists perceived there to be a lack of guidance to inform their practice and work with gender diverse CYP (Betts, 2013; Bowskill, 2017), with a desire for more interest and support in the area from national governing bodies such as the National Association of School Psychologists (Betts, 2013).

How do I know what to do?

Working in such turbulent and varying contexts, with limited legal guidelines, psychologists often looked to their own views and values to guide their work. Values of inclusion, acceptance, and social justice (Betts, 2013; Gonzalez, 2016; Sagzan, 2019), alongside individualized and open-minded approaches (Beck, 2018; Betts, 2013) were central to psychologists’ work. Views around gender diversity more specifically interacted with these underpinning values to further shape their work. Psychologists varied in their view of what they thought gender was, for example, viewing it either as a fixed entity, a societal construct, or a spectrum of identities (Sagzan, 2019) and acknowledged that individuals’ “personal attitudes and beliefs about LGBTQ individuals impact their willingness to intervene” and their approach to support (Reisner et al., 2020). Therefore, psychologists developing an awareness of and challenging their own assumptions and biases around gender was important to support their work in this area (Court, 2019; Gonzalez, 2017; Mackie et al., 2021; Sagzan, 2019).

Psychologists’ views and values interacted with their knowledge of gender diversity. Knowledge was seen as central to developing and guiding practice as well as “aiding effective support” (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Apostolidou, 2020; Betts, 2013). Learning through their own or others lived experiences as a member of the LGBTQ community was highly valued (Beck, 2018, 2020; Betts, 2013; Swindle, 2022). Often this personal connection motivated psychologists to seek further information to aid their understanding (Gavin, 2021; Simons & Cuadrado, 2019), empowered psychologists in their work, and instilled a level of confidence in their approaches (Betts, 2013; Court, 2019). Increased awareness of the context around gender diversity and the potential detrimental impact for CYP also motivated psychologists, highlighting the difference that their work could make (Betts, 2013; Gonzalez, 2016, 2017; Mackie et al., 2021; Swindle, 2022). Nonetheless, psychologists recognized a need for “much more than just knowledge” (Betts, 2013). To go against the dominant hetero and cisnormative discourse often embedded in the context in which they are working, a level of courage, confidence, and strength was needed (Apostolidou, 2020; Betts, 2013).

In addition, psychologists’ perception of their role and the skills that they had to offer influenced their work. Psychologists drew on many areas of practice to support their work with gender diverse CYP, such as consultation and interpersonal skills, re-framing, Person Centered Practices and working with parents (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Betts, 2013; Bowskill, 2017; Court, 2019; Gavin, 2021). How psychologists viewed and contracted their role with stakeholders, therefore impacted the work they carried out (Sagzan, 2019), drawing on their existing toolkits to support them, though time constraints, school priorities, and competing demands limited their involvement (Gavin, 2021; Gonzalez, 2016). The diversity in the role is something that both attracted psychologists to the profession and provided a source of frustration in relation to the amount of time they had available to learn more and to provide support to gender diverse pupils (Betts, 2013; Gavin 2021).

Advocacy is central to my work

Driven by their values and knowledge, psychologists experienced their role in being an advocate for, and role model to, gender diverse CYP as central to their practice (Beck, 2018; Gavin, 2021; Gonzalez, 2017; Swindle, 2022; Yannalfo, 2019). Being open about their own LGBTQ identity allowed some psychologists to act as a positive role model for students (Beck, 2018, 2020; Gonzalez, 2017) and promote visibility and representation. However, safety in identifying as cisgender and heterosexual in advocacy work was also recognized (Betts, 2013). Nonetheless, personal experience or connection with the LGBTQ community was again highlighted as a key motivator in psychologists advocacy work (Beck, 2020; Betts, 2013; Gavin, 2021; Simons & Cuadrado, 2019), with an aim to develop shared values toward the LGBTQ community (Beck, 2020).

Psychologists further advocated through educating others, from individuals to whole school staff and beyond (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Gavin, 2021; Gonzalez, 2017; Reisner et al., 2020). This helped raise awareness, increase understanding, and ensure others working with gender diverse CYP were up to date with key information, language, and practice. There was a need for psychologists to not only educate others but to challenge individuals and systems. Psychologists worked to challenge implicit assumptions, discrimination and bullying at an individual level (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Betts, 2013; Yannalfo, 2019) as well as the dominant binary model of gender ingrained in education and society (Bowskill, 2017; Reisner et al., 2020). Through educating and challenging others, psychologists hoped to encourage systems to be more inclusive of LGBTQ students (Beck, 2018; Bowskill, 2017) and inspire others to become advocates to improve outcomes and support for gender diverse CYP (Beck, 2020; Reisner et al., 2020).

Psychologists recognized that they could not do this alone; linking with other professionals, participating in professional organizations, and collaborating with key stakeholders supported their advocacy work (Betts, 2013; Court, 2019; Gonzalez, 2017; Sagzan, 2019). Psychologists saw a role in listening to the views of key adults, and where appropriate assisting collaboration between CYP and key adults in their life (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Bowskill, 2017; Gavin, 2021; Vela, 2015). Consistent with this was a belief expressed that an individualized approach to support was vital, recognizing that “not all students fit into the same peg” (Beck, 2018). Whilst knowledge around gender diversity more generally was deemed important (as mentioned in the previous theme), psychologists were aware that a careful balance needed to be struck to ensure they also saw each young person as an individual with their own strengths, needs and ways to be supported (Gavin, 2021). Intersectionality added a further layer of complexity (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Betts, 2013; Bowskill, 2017; Gavin, 2021) and was an additional driver for an individualized approach, but psychologists recognized that there was an even sparser understanding of, and guidelines for, intersecting identities such as race, neurodiversity, and gender (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022).

When advocating for a personalized approach, psychologists placed a significant emphasis on giving priority and value to the perspectives of CYP (Beck, 2018; Bowskill, 2017; Gavin, 2021; Mackie et al., 2021; Swindle, 2022). They drew on the expertise of the CYP with whom they were working and empowered them to feel like the expert in their own experiences (Beck, 2020; Mackie et al., 2021). This supported psychologists’ confidence and practice, allowing them to learn from the lived experiences of gender diverse CYP helping them feel valued, listened to, and supported. In addition, psychologists worked to empower CYP to advocate for themselves and others (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Beck, 2018, 2020; Gonzalez, 2017; Swindle, 2022). This empowerment was achieved through individual work with the CYP as well as educating them and others about gender diversity and identity to further raise awareness and understanding (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Bowskill, 2017; Gavin, 2021).

Supporting CYP’s sense of belonging and acceptance was central to psychologists’ advocacy (Gavin, 2021; Sagzan, 2019). The creation of safe, nonjudgmental spaces where LGBTQ students could authentically be themselves (Beck, 2018; Mackie et al., 2021; Vela, 2015) was seen as an important part of their role. Psychologists felt a need to de-stigmatise and normalize CYPs experiences given the current context and stigma often associated with gender diversity (Bowskill, 2017; Gonzalez, 2017; Mackie et al., 2021). De-stigmatisation offered CYP validation and acceptance, something psychologists recognized they might not have experienced previously (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022).

I am fighting against barriers and systems

Whilst psychologists in the reviewed studies were guided by their values and knowledge to advocate for gender diverse CYP, they recognized several barriers to providing effective support. They identified that a widespread lack of knowledge and training is maintaining an environment in which individuals’ fear of getting it wrong leads to relative hesitancy and inaction related to gender diversity (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Court, 2019; Gavin, 2021; Sagzan, 2019) and an under identification of transgender pupils needing support in schools (Sagzan, 2019; Vela, 2015). Psychologists reported that gender diversity was often overlooked in graduate training programmes (Beck, 2020; Court, 2019; Sagzan, 2019; Swindle, 2022), leaving large disparities in the knowledge and awareness of practising psychologists. Further, psychologists perceived a significant barrier to their knowledge and effective support was a lack of evidence-base in the area, with a need for greater research to support their work (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Betts, 2013; Vela, 2015). Psychologists similarly recognized the need for school staff they are working with to receive greater training around gender diversity (Apostolidou, 2020; Bowskill, 2017; Sagzan, 2019; Vela, 2015).

Psychologists’ experience of their work in the area was inextricably linked to the political landscape in which they were situated. Politically gender diversity was recognized to have become a “hot topic” due to increased visibility and discussion in the area (Court, 2019), with barriers often related to patriarchal and conservative climates (Apostolidou, 2020; Beck, 2020; Betts, 2013; Simons & Cuadrado, 2019). In these situations, psychologists felt their hands were tied due to fear of negative outcomes, such as being fired, if they were to support gender diverse CYP (Simons & Cuadrado, 2019). Tolerance and acceptance of others toward gender diversity was also linked to certain religious contexts and posed a barrier to psychologists supporting students and systems (Betts, 2013; Gonzalez, 2016; Simons & Cuadrado, 2019; Swindle, 2022).

These disparate political and religious contexts caused psychologists a great deal of conflict in their work. The varying levels of knowledge, awareness, understanding, and acceptance around gender diversity meant psychologists were met with mixed views from those with whom they worked (Beck, 2018; Betts, 2013; Gonzalez, 2016). Often views in the area were “polarized in their origin” (Court, 2019) and represented the stark contrast psychologists experienced in managing the conflicting views of parents, families, school staff and CYP (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Apostolidou, 2020; Court, 2019; Gavin, 2021; Mackie et al., 2021), leading to a range of approaches to support. Psychologists reflected on their role in shifting the perspectives of those with whom they were working (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022; Beck, 2018, 2020), though the readiness of others to engage in the process of change related to gender diversity influenced how successfully psychologists were able to shift perspectives (Court, 2019; Gavin, 2021; Sagzan, 2019).

In the context of the political landscape and the associated conflict, psychologists were aware of the impact of stigma and prejudice on their work and the wider context. Firstly, psychologists highlighted the prevalence of transphobic bullying in schools which is often “not addressed adequately” (Apostolidou, 2020) and impacted on CYP’s wellbeing (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022). This gender-based bullying emphasized the prevailing prejudice and binarized assumptions against which psychologists were battling (Apostolidou, 2020; Gonzalez, 2016; Sagzan, 2019). An additional barrier was that gender was seen by many as a “taboo area” (Gavin, 2021), that should not be talked about (Apostolidou, 2020; Court, 2019; Sagzan, 2019), and when the subject was broached, dependent on the context in which they worked, psychologists risked backlash from their work in terms of complaints, being marginalized themselves or losing their jobs (Apostolidou, 2020; Betts, 2013; Gonzalez, 2016; Simons & Cuadrado, 2019).

Discussion

The current qualitative review aimed to explore the perspectives and experiences of school-based psychological professionals providing support to gender diverse CYP. Psychologists in the reviewed studies found themselves working in ever-changing environments and contexts related to gender diversity and often searched for a map to guide their way, in the form of professional guidance. When no map was found, psychologists were guided by their own principles and values, and drew on their existing knowledge and tools to advocate for gender diverse CYP through their work. These findings support previous quantitative literature emphasizing the influence of prior experience and training, as well as individuals’ attitudes and values, to the confidence and engagement of school-based psychologists’ work supporting gender diverse CYP (Goodrich, 2017; Meier, 2019; Stathatos, 2020).

The synthesis highlighted several barriers that impacted psychologists’ work with gender diverse CYP, aligning closely with previous research in the area, including the prevalent cisnormative discourse in schools (McBride, 2021), widespread lack of training for both school staff and psychologists (Payne & Smith, 2014; Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2015), and conflicting views of those they work with (Kuff et al., 2019). Psychologists further alluded to varying roles they can adopt in the area to promote positive outcomes for gender diverse CYP, alongside examples of good practice. The second objective of this review was to examine the themes capturing the perspectives of school-based psychologists who have experience supporting gender-diverse children and young people, to consider how these insights might guide future professional practices. Firstly, the environment within which psychologists work plays an important role in the support they can offer. The importance of inclusive environments for gender diverse CYP is reinforced by psychologists throughout the synthesis as well as previous research (Greytak et al., 2013; Rivas-Koehl et al., 2022; Russell et al., 2014), yet too often school support is implemented reactively when a specific need arises (Davy & Cordoba, 2020). School-based psychologists are well positioned to consider systemic and proactive support in schools as a priority for gender diverse CYP and utilize their influence across the range of levels within which they work. Getting to know the values and ethos of the schools and leadership teams psychologists work with was identified as a helpful starting point for inciting change where needed, as well as promoting key aspects related to inclusivity. Some ideas shared from psychologists in the current review include increased LGBTQ + visibility throughout the environment and curriculum (Beck, 2018; Bowskill, 2017; Gonzalez, 2017) and wider support from administrative teams (Gonzalez, 2016). This is not without challenges though, as the political, religious, and legal contexts pose barriers for psychologists. It is also acknowledged that where an individual or school is in relation to their readiness to change, will impact how effectively psychologists can support shifts in attitudes and approaches. It is therefore important for psychologists to draw on other aspects of their knowledge base, such as Wang et al.’s (2020) framework of system readiness to change and cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), to support them in this work.

A further, though related, implication links to knowledge and understanding. Psychologists identified a key role they have around increasing knowledge, awareness and understanding of gender diversity, through avenues such as educating and challenging others and delivering training. Previous research supports this as an important and necessary role for psychologists due to school staff regularly reporting they do not feel confident or equipped to support gender diverse CYP (Collier et al., 2015; Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2015). Whilst this is therefore an important aspect of psychologists’ work, research suggests that psychologists themselves often do not have the necessary knowledge to fulfill this (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2015). In the current synthesis, psychologists discussed knowledge as both a facilitator and barrier to effective support and highlighted that gender diversity is currently not included as standard in graduate psychology training programmes, leading to large disparities in the knowledge bases of practising psychologists. To address these disparities, it will be important for all school-based psychological professionals to receive training in the area and for this to be incorporated into graduate training programmes. Research indicates that psychologists with more training in the area engage in more work to support gender diverse CYP and did so with increased confidence (Meir, 2019), thus reinforcing the importance of this.

Additionally, the current review highlighted that psychologists rely on their individual views and values to steer them in their work with gender diverse CYP. Support for gender diverse CYP is thus likely to be highly varied, leading to large discrepancies in associated outcomes. This variability highlights a need for specific guidance to be developed to guide school-based psychological professionals in this work to ensure effective and consistent support is in place for pupils. Gender inclusive policies in schools have been associated with improved outcomes for gender diverse CYP, such as increased attendance (Greytak et al., 2013) and more positive school experiences (Day et al., 2019), reinforcing the power of such policies and guidelines.

The current review further highlighted the clear role school-based psychologists have as advocates for gender diverse CYP to promote inclusive, supportive environments where all CYP can flourish. It is important to note however, that just because CYP are gender diverse does not mean they need direct support from a psychologist, as this risks pathologising the identity of these individuals. Advocacy work therefore needs to take this into account, with examples of good practice being shared in which psychologists challenged individuals, as well as wider systems, were transparent about their views and inclusive ethos, prioritized the voices of CYP and promoted acceptance and belonging for gender diverse CYP.

Strengths, limitations, and future research

The use of thematic synthesis in the current review allowed the voices of school-based psychological professionals working in diverse contexts to be brought together, to learn from their experiences and consider how practice in the area can be supported. It extended previous reviews by including grey literature and focussing on those with experience of working with gender diverse CYP.

Nonetheless, the nature of a qualitative synthesis means the review is steered by the voices of those in the included studies. Although steps were taken to incorporate global research, studies identified were based in USA, Australia, and Europe meaning views across broader contexts may not be represented. This is particularly pertinent given the different conceptualisations of gender across cultures (Howell & Allen, 2021; Schmidt, 2016). Furthermore, due to the focus on those with experience in the area, it is likely a biased sample representing those with similar viewpoints, particularly in a field where views are reportedly polarized (Court, 2019). Indeed, many participants included were either LGBTQ + themselves or had close connections to the LGBTQ + community, likely shaping their views and actions. It will therefore be important for future research to draw on a wider range of viewpoints, including those who may be less likely to engage in such work, to consider further how practice in the area can best support the needs of gender diverse CYP.

Over half of the studies included focussed on LGBTQ + populations more broadly (e.g. Simons & Cuadrado, 2019; Swindle, 2022; Vela, 2015). Where possible, only data focussing on psychologists work with gender diverse CYP was included in the current review, however this was not always distinguishable. Research indicates that gender and sexuality diverse pupils have different experiences, with higher rates of victimization and abuse directed toward gender diverse CYP compared to cisgender lesbian, gay and bisexual peers for example (Day et al., 2018; Ullman, 2017). Further research is therefore needed to explore school-based psychologist’s work solely with gender diverse CYP.

It was beyond the scope of this review to explore the quantitative literature in the area, despite the search strategy identifying several related papers. Future work could synthesize this research to further consider factors that influence school-based psychologists work with gender diverse CYP. The focus of this review was also not on the voices of CYP themselves. This is undoubtedly a limitation, and the sparsity of research suggests that considering gender diverse CYP’s experiences of working with school-based psychological professionals would be important to inform future practice and policy.

Finally, intersectionality was mentioned by psychologists as adding further complexity to their work with gender diverse CYP, yet is often ignored by research and policy. One study included in the review focussed on the intersection of gender and neurodiversity (Allen-Biddell & Bond, 2022), however further research is required to explore intersecting identities and consider the impact on psychologist’s work.

Conclusion

Research indicates that school-based professionals have mixed levels of preparedness and confidence when it comes to working with gender diverse CYP, despite being very likely to encounter gender diversity in their practice. The current review first aimed to synthesize the perspectives of school-based psychologists who have engaged in such work. Four themes encapsulate their experiences and, in line with the second aim of the review, these provided the basis for consideration of the implications for future practice. The review underscores the advocacy role of psychologists in support of gender diverse CYP, while also highlighting the barriers they encounter. The importance of the environment was clear, emphasizing the need for school-based psychologists to work systemically with schools in supporting gender diverse CYP to promote inclusive environments and policies.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ajzen, I. (2015). The theory of planned behaviour is alive and well, and not ready to retire: A commentary of Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 131–137. 10.1080/17437199.2014.883474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanen, L. (2015). Are we all constructionists now? Childhood, 22(2), 149–153. 10.1177/0907568215580624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen-Biddell, D., & Bond, C. (2022). What are the experiences and practices of educational psychologists when working with and supporting autistic, gender-diverse children and young people? Educational and Child Psychology, 39(1), 76–87. 10.53841/bpsecp.2022.39.1.76 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (APA) (2023). Understanding transgender people, gender identity and gender expression. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/lgbtq/transgender-people-gender-identity-gender-expression [Google Scholar]

- Apostolidou, Z. (2020). Homophobic and transphobic bullying within the school community in Cyprus: A thematic analysis of school professionals’, parents’ and children’s experiences. Sex Education, 20(1), 46–58. 10.1080/14681811.2019.1612347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arora, P. G., Kelly, J., & Goldstein, T. R. (2016). Current and future school psychologists’ preparedness to work with LGBT students: Role of education and gay-straight alliances. Psychology in the Schools, 53(7), 722–735. 10.1002/pits.21942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin, A., & Craig, S. L. (2015). Empirically supported interventions for sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 12(6), 567–578. 10.1080/15433714.2014.884958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomaeus, C., & Riggs, D. W. (2017). Whole-of-school approaches to supporting transgender students, staff, and parents. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(4), 361–366. 10.1080/15532739.2017.1355648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, M. J. (2018). “Lead by example”: A phenomenological study of school counselor–principal team experiences with LGBT students. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1–13. 10.1177/2156759X18793838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, M. J. (2020). “It began with me”: An exploration of exemplary school counselor and principal experiences with LGBT students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 17(4), 432–452. 10.1080/19361653.2019.1680591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, J. (2014). Rapid qualitative inquiry: A field guide to team-based assessment (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, E. C. (2013). Fostering LGBTQ advocacy in school psychology as adult education: Shaping attitudes, beliefs, and perceived control [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Pennsylvania State University. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, A., Cherry, G., & Dickson, R. (2017). Doing a systematic review: A student’s guide. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Bower-Brown, S., Zadeh, S., & Jadva, V. (2021). Binary-trans, non-binary and gender-questioning adolescents’ experiences in UK schools. Journal of LGBT Youth, 20(1), 74–92. 10.1080/19361653.2021.1873215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, S., Lewandowski, J., Savage, T. A., & Woitaszewski, S. A. (2015). School psychologists’ attitudes toward transgender students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 12(1), 1–18. 10.1080/19361653.2014.930370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowskill, T. (2017). How educational professionals can improve the outcomes for transgender children and young people. Educational and Child Psychology, 34(3), 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Britten, N., Campbell, R., Pope, C., Donovan, J., Morgan, M., & Pill, R. (2002). Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7(4), 209–215. 10.1258/135581902320432732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, A., & Mayock, P. (2017). Supporting LGBT lives? Complicating the suicide consensus in LGBT mental health research. Sexualities, 20(1–2), 65–85. 10.1177/1363460716648099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, G., De Graaf, N., Wren, B., & Carmichael, P. (2018). Assessment and support of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 103(7), 631–636. 10.1136/archdischild-2018-314992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier, K. L., Bos, H. M. W., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2015). Understanding teachers’ responses to enactments of sexual and gender stigma at school. Teaching and Teacher Education, 48, 34–43. 10.1016/j.tate.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin, S., Egan, J. E., & Coulter, R. W. S. (2019). School climate & sexual and gender minority adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(10), 1938–1951. 10.1007/s10964-019-01108-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M. D., Zervos, M. J., Barone, C. J., Johnson, C. C., & Joseph, C. L. M. (2016). The mental health of transgender youth: Advances in understanding. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 59(5), 489–495. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, R. W. S., Bersamin, M., Russell, S. T., & Mair, C. (2018). The effects of gender- and sexuality-based harassment on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender substance use disparities. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 62(6), 688–700. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court, E. (2019). Gender variance and the role of the Educational Psychologist (EP) : An exploration of the perspectives of EPs and Trainee Educational Psychologists (TEPs) in Wales [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Cardiff University. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . (2018). CASP qualitatitve checklist [online]. Retrieved November 2022, from https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf.

- Davy, Z., & Cordoba, S. (2020). School cultures and trans and gender-diverse children: Parents’ perspectives. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 16(4), 349–367. 10.1080/1550428X.2019.1647810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Day, J. K., Fish, J. N., Perez-Brumer, A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Russell, S. T. (2017). Transgender youth substance use disparities: Results from a population-based sample. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 61(6), 729–735. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day, J. K., Ioverno, S., & Russell, S. T. (2019). Safe and supportive schools for LGBT youth: Addressing educational inequities through inclusive policies and practices. Journal of School Psychology, 74(January), 29–43. 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day, J. K., Perez-Brumer, A., & Russell, S. T. (2018). Safe Scho44ols? Transgender youth’s school experiences and perceptions of school climate. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1731–1742. 10.1007/s10964-018-0866-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessel, A. B., Kulick, A., Wernick, L. J., & Sullivan, D. (2017). The importance of teacher support: Differential impacts by gender and sexuality. Journal of Adolescence, 56(1), 136–144. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., Hsu, R., Katbamna, S., Olsen, R., Smith, L., Riley, R., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 35. 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisko, J. W. (2020). Qualitative research synthesis: An appreciative and critical introduction. Qualitative Social Work, 19(4), 736–753. 10.1177/1473325019848808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw, V. A., Menino, D. D., Sava, L. M., Perrotti, J., Barnes, T. N., Humphrey, D. L., & Reisner, S. L. (2020). LGBTQ bullying: A qualitative investigation of student and school health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fallon, K., Woods, K., & Rooney, S. (2010). A discussion of the developing role of educational psychologists within Children’s Services. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26(1), 1–23. 10.1080/02667360903522744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin, J. (2021). [Building a better understanding of how educational professionals engage with systems to support trans* young people] [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. UCL Institute of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M. (2016). Factors that facilitate and impede school counselor advocacy for and with LGBT students. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 3(2), 158–172. 10.1080/2326716X.2016.1147397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M. (2017). Advocacy for and with LGBT students: An examination of high school counselor experiences. Professional School Counseling, 20(1a), 38–46. 10.5330/1096-2409-20.1a.38 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, M., Adams, N., Corneil, T., Kreukels, B., Motmans, J., & Coleman, E. (2019). Size and distribution of transgender and gender nonconforming populations: A narrative review. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 48(2), 303–321. 10.1016/j.ecl.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, K. M. (2012). Lived experiences of college-age transsexual individuals. Journal of College Counseling, 15(3), 215–232. 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00017.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, K. M. (2017). Exploring school counselors’ motivations to work with LGBTQQI students in schools: A Q methodology study. Professional School Counseling, 20(1a), 1096-2409-20.1a. 10.5330/1096-2409-20.1a.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greytak, E. A., Kosciw, J. G., & Boesen, M. J. (2013). Putting the “T” in “Resource”: The benefits of LGBT-related school resources for transgender youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 10(1-2), 45–63. 10.1080/19361653.2012.718522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J. S., & Garbarino, J. (2012). Risk and protective factors for homophobic bullying in schools: An application of the social-ecological framework. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 271–285. 10.1007/s10648-012-9194-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, T., & Allen, L. (2021). ‘Good morning boys’: Fa’afāfine and Fakaleiti experiences of Cisgenderism at an all-boys secondary school. Sex Education, 21(4), 417–431. 10.1080/14681811.2020.1813701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johns, M. M., Beltran, O., Armstrong, H. L., Jayne, P. E., & Barrios, L. C. (2018). Protective factors among transgender and gender variant youth: A systematic review by socioecological level. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 39(3), 263–301. 10.1007/s10935-018-0508-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T., Smith, E., Ward, R., Dixon, J., Hillier, L., & Mitchell, A. (2016). School experiences of transgender and gender diverse students in Australia. Sex Education, 16(2), 156–171. 10.1080/14681811.2015.1080678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino, R., Bergman, H., Työläjärvi, M., & Frisén, L. (2018). Gender dysphoria in adolescence: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 9, 31–41. 10.2147/ahmt.s135432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Giga, N. M., Villenas, C., & Danischewksi, D. J. (2015). The 2015 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED574780.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Zongrone, A. D., Clark, C. M., & Truong, N. L. (2018). The 2017 national school climate survey. GLSEN. www.glsen.org/research. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw, J. G., & Pizmony-Levy, O. (2016). International perspectives on homophobic and transphobic bullying in schools. Journal of LGBT Youth, 13(1–2), 1–5. 10.1080/19361653.2015.1101730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuff, R. M., Greytak, E. A., & Kosciw, J. G. (2019). Supporting safe and healthy schools for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer students: A national survey of school counselors, social workers, and psychologists. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). https://www.proquest.com/reports/supporting-safe-healthy-schools-lesbian-gay/docview/2228677216/se-2?accountid=13963 [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, M., & Thompson, A. R. (2012). Interpretative phenomenological analysis in mental health and psychotherapy research. In Harper D. & Thompson A. R. (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, M. (2019). Growing up trans: Exploring the positive school experiences of transgender children and young people [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of East London. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, M. (2022). ‘It was probably one of the best moments of being trans, honestly!’: Exploring the positive school experiences of transgender children and young people. Educational and Child Psychology, 39(1), 44–59. 10.53841/bpsecp.2022.39.1.44 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie, G., Lambert, K., & Patlamazoglou, L. (2021). The experiences of psychologists working with transgender young people in school counselling: An Australian sample. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 36(1), 1–24. 10.1080/09515070.2021.2001313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBride, R. S. (2021). A literature review of the secondary school experiences of trans youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 18(2), 103–134. 10.1080/19361653.2020.1727815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBride, R. S., & Schubotz, D. (2017). Living a fairy tale: The educational experiences of transgender and gender non-conforming youth in Northern Ireland. Child Care in Practice, 23(3), 292–304. 10.1080/13575279.2017.1299112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, E., Hughes, E., & Rawlings, V. (2018). The social determinants of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth suicidality in England: A mixed methods study. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 40(3), e244–e251. 10.1093/pubmed/fdx135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, J. K., Anderson, C. R., Toomey, R. B., & Russell, S. T. (2010). School climate for transgender touth: A mixed method investigation of student experiences and school responses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1175–1188. 10.1007/s10964-010-9540-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, N. M. (2019). [An examination of school psychologists exposure to and preparedness to support transgender students in schools] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Loyola University Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Nodin, N., Peel, E., Tyler, A., & River, I. (2015). The RaRE research report: LGB&T mental health - risk and resilience explored. PACE. https://openresearch.lsbu.ac.uk/download/b9904f6f84a51fe2db1a91b4b1e0604d0ccc1bc950d5cb42f62e4126d14cad67/2851990/RAREResearchReport_PACE20150422corrected.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne, E., & Smith, M. (2014). The big freak out: Educator fear in response to the presence of transgender elementary school students. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(3), 399–418. 10.1080/00918369.2013.842430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne, J. (2014). Gender independent kids: A paradigm shift in approaches to gender non-conforming children. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 23(1), 1–8. 10.3138/cjhs.23.1.CO1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner, S. L., Sava, L. M., Menino, D. D., Perrotti, J., Barnes, T. N., Humphrey, D. L., Nikitin, R. V., & Earnshaw, V. A. (2020). Addressing LGBTQ student bullying in Massachusetts schools: Perspectives of LGBTQ students and school health professionals. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 21(3), 408–421. 10.1007/s11121-019-01084-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, D. W., & Bartholomaeus, C. (2015). The role of school counsellors and psychologists in supporting transgender people. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 32(2), 158–170. 10.1017/edp.2015.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Koehl, M., Valido, A., Espelage, D. L., Robinson, L. E., Hong, J. S., Kuehl, T., Mintz, S., & Wyman, P. A. (2022). Understanding protective factors for suicidality and depression among US Sexual and gender minority adolescents: Implications for school psychologists. School Psychology Review, 51(3), 290–303. 10.1080/2372966X.2021.1881411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S. T., Toomey, R. B., Ryan, C., & Diaz, R. M. (2014). Being out at school: The implications for school victimization and young adult adjustment. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 635–643. 10.1037/ort0000037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagzan, E. R. (2019). [There’s a long way to go” : Educational psychologists’ perceptions of their role in supporting schools to improve outcomes for trans* students] [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust and University of Essex. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J. (2016). Being ‘like a woman’: Fa’afāfine and Samoan masculinity. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 17(3–4), 287–304. 10.1080/14442213.2016.1182208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q., & Doud, S. (2017). An examination of school counselors’ competency working with lesbian, gay and bisexual and transgender (LGBT) students. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 11(1), 2–17. 10.1080/15538605.2017.1273165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons, J., & Cuadrado, M. (2019). Narratives of school counselors regarding advocacy for LGBTQ students. Professional School Counseling, 22(1), 2156759X1986152. 10.1177/2156759X19861529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory method and research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]