Abstract

Decades of significant crime declines and recent reductions in the number of people confined in prisons and jails in the United States have been accompanied by the emergence of new, and the resurgence of old, forms of punishment. One of these resurgent forms is the assessment of fines, fees, and costs to those who encounter the criminal legal system. Legal financial obligations (LFOs) have become widespread across the United States and are levied for offenses from alleged traffic violations in some states to felony convictions in others. Their emergence has been heralded by some as a less punitive alternative to spending time in prison or jail but recognized by others as uniquely consequential for people without the means to pay. Drawing on data from 254 counties in Texas, this article explores the emergence and enforcement of LFOs in Texas, where LFOs play a particularly prominent role in sanctions for alleged misdemeanor offenses and serve as an important source of revenue. Enforcement of LFOs varies geographically and is related to conservative politics and racial threat. We argue that LFOs are a defining feature of a contemporary punishment regime where racial injustice is fueled by economic inequality.

Keywords: monetary sanctions, punishment, misdemeanors, inequality, race

While crime rates in the United States peaked in the mid-1990s, and the prison and jail population has declined since 2009, other forms of punishment have proliferated. Historic growth in the penal system through the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, coupled with expansions in the use of community-based supervision such as probation, fueled increases in the number of people subject to on-going surveillance by the criminal legal system. Estimates suggest that 19 million people living in the United States have a felony conviction (Shannon et al. 2017:1806). Routine traffic stops, misdemeanor arrests, and other surveillance mechanisms net tens of millions more individuals into the criminal legal system and serve as an important source of revenue for local jurisdictions (Baumgartner, Epp, and Shoub 2018; Kohler-Hausmann 2018; Phelps 2017).

A great deal of scholarship has demonstrated the negative consequences of imprisonment, and other forms of justice involvement, on a host of outcomes from employment and earnings to health and well-being (see, for example, Kirk and Wakefield 2018 or Turney and Wakefield 2019 for reviews). Even in the absence of conviction, seemingly minor contacts with the police can have enduring consequences (Lerman and Weaver 2014), including demands for repeated court appearances (Herring, Yarbrough, and Marie Alatorre 2019; Kohler-Hausmann 2018), court-mandated program participation (Pretrial Justice Institute 2010), and the assessment of fines and fees (Harris 2016; Martin et al. 2018). The expansion of criminal punishments into civil and administrative legal bodies has been characterized as a “shadow carceral state” (Beckett and Murakawa 2012), a system that, while elusive, exacts both symbolic and material punishments.

One important dimension of the shadow carceral state is the routine assessment of legal fines and fees. Judicial systems around the world have long assessed fines as punishment for wrongdoing (Sutherland and Cressey 1934) and used financial incentives, like money bail, to assure compliance with court ordered appearances and obligations (Schnacke, Jones, and Brooker 2010). Day fines are a common criminal justice sanction in many parts of Europe (Hillsman 1990) and cataloging the full extent and implications of fines, fees, court costs, and other financial sanctions in the United States is of increasing interest and concern (U.S. Department of Justice 2015). Individuals who encounter the U.S. criminal legal system can be sentenced to pay fines or charged fees ostensibly for a wide range of encounters with police, courts, or corrections. In many jurisdictions, such as Ferguson, Missouri, and El Paso, Texas, fines and fees associated with relatively minor offenses are pervasive and may be assessed even in the absence of a criminal conviction (Taggart and Campbell 2015; U.S. Department of Justice 2015). Estimates suggest that nationwide, 66 percent of prison inmates have been sentenced to pay some amount of money to the courts or other criminal justice agencies, up from just 25 percent in 1991 (Harris, Evans, and Beckett 2010:1769).

Despite growing interest and concern in the prevalence and consequence of exposure to legal financial obligations (LFOs), relatively little research has described or explained their proliferation and how they might be understood in relation to other forms of punishment such as the death penalty, incarceration, or community-based supervision. There are important reasons to think that explanations for other forms of punishment may, or may not, be relevant to legal fines and fees. Fines and fees are often conceptualized as alternatives to harsher sanctions like incarceration. As one legal scholar puts it, “Nonprison sentences … allow – and even require – individuals to be employed, pay fines and make restitution, pay taxes, and assist their families. Such demands are crucial to allowing them to regain their place in society” (Demleitner 2005:346). Others have suggested that the use of fines can help eliminate the discrimination that leads to overrepresentation of minorities in the criminal justice system (Curry and Klumpp 2007). This line of reasoning suggests that the factors associated with the prevalence and implementation of legal fines and fees should contrast with those associated with harsher penalties.

Alternatively, the use of legal fines and fees may be conceptualized as an enhancement1 to other forms of punishment. Consistent with this line of reasoning, previous research has shown that fines are often levied on top of and in conjunction with harsher sentences (Harris 2016). In this case, we would expect explanations for the use of fines and fees to be consistent with those relevant for other forms of punishment. Trends in incarceration and the use of the death penalty point to the causal relevance of political, economic, and racial tensions for understanding punitive jurisprudence (Jacobs and Carmichael 2001; Jacobs and Helms 1996; Sutton 2004; Tonry 1995). However, there is relatively little research examining the relevance of these explanations for the reemergence and expansion of legal fines and fees.

Drawing on over-time data from 254 counties in Texas, this paper describes the rise and prevalence of legal fines and fees for relatively minor misdemeanor charges and examines whether and to what extent theories used to explain other, arguably more punitive forms of punishment, inform their proliferation. Texas is a large Southern state with a history of punitive penology and recent notoriety for its efforts at penal reform. Since the demise of convict leasing, and through an era of penal expansion, the assessment and collection of monetary sanctions has undergirded judicial operations and community supervision across the state. Today, legal fines and fees in Texas are levied routinely and far more often than they were in the past, rising from around $700 million in the mid-1990s to over $1.2 billion (Texas Office of Court Administration 2018). This includes minor infractions, such as alleged traffic offenses, and is in conjunction with more severe sanctions, such as mandated time in jail or prison; collection is essential to the funding and functioning of community-based supervision programs, including parole and probation (Martin et al. 2018; Slayton 2014).

By leveraging data within one large yet diverse state over time, we explore geographic variation in the collection of fines and fees and how factors that help explain patterns of punishment measured by incarceration, for example, are relevant for understanding the expansion and enforcement of legal fines and fees at the misdemeanor level. Results show significant variation across jurisdictions and establish that the routine assessment and collection of legal fines and fees widens the net of justice involvement and intensifies punishments in unequal and enduring ways. While the imposition of legal fines and fees is widespread and affects millions of Texans each year, their imposition and enforcement are concentrated in ways that align with historical patterns of inequality in, arguably, more serious forms of punishment. Outstanding legal fines and fees legitimate on-going surveillance and social control of people who are unable to pay. For example, legal scholars argue that police and courts have been given great latitude with regard to the Fourth Amendment to impose and collect fines and fees (Brett forthcoming; Woods 2015). Existing patterns of political, racial, and ethnic inequality concentrates exposure to and consequences of legal fines and fees. As such, the imposition and enforcement of legal fines and fees can be understood as an increasingly important element of contemporary American penology and yet another weapon in the arsenal of surveillance and control of historically marginalized populations.

LEGAL FINES AND FEES IN THE FIELD OF PUNISHMENT

The United States’ decentralized system of criminal surveillance and punishment has resulted in significant over-time and across-jurisdiction variability in punishment practices. Arguably, the most severe of these practices is the death penalty, which deprives people of liberty and life. The United States permits the death penalty, and it is legally authorized in 29 states. Although the number of executions has declined in the past two decades, people continue to be executed for convictions of criminal wrongdoing in a concentrated number of states. In the 10-year period from 2009–2018, Georgia, Florida, and Texas executed 22, 31, and 135 people, respectively (Death Penalty Information Center 2019). Incarceration, another serious and intensive form of punishment, also varies dramatically over time and across states. Recent data show that the incarceration rate ranges from .34 percent of the adult population in Vermont to 1.3 percent—over 1 in 100 adults—in Oklahoma in 2016 (Kaeble and Cowhig 2016). Exposure to incarceration is concentrated further still among men, people of color, and those with low levels of formal schooling.

These patterns of punishment have led scholars and others to characterize different jurisdictions as more, or less, punitive or variably “tough” or “soft” on crime. Prior research seeking to explain observed patterns of punishment commonly emphasizes the relevance of political, demographic, and economic conditions for understanding trends in, and contours of, the legality and exercise of punishments like the death penalty and confinement in prisons and jails (Jacobs and Carmichael 2001; Jacobs and Helms 1996; Sutton 2004; Tonry 1995). Scholarship has also emphasized how a wide range of factors, from racialized politics to a punitive public, help not only to explain historical patterns of punishment, including the growth of mass incarceration, but also its concentration among young, disproportionately Black, men living in historically disadvantaged communities (Campbell and Schoenfeld 2013; Enns 2016; Hinton 2016; Schoenfeld 2018).

Although mass incarceration has declined over the past decade, the use of different forms of punishment has expanded and widened the scope of criminal justice contact and shifted supervision from prisons and jails to courtrooms and communities (Brayne 2014; Kohler-Hausmann 2018; Stuart 2016). The number of people subject to legal fines and fees has grown dramatically in the past few decades. For example, one study found that in 2004, two-thirds of prison inmates had been assessed fines and fees, up from only one-fourth of prison inmates in 1991 (Harris et al. 2010:1769). Moreover, fines and fees associated with justice involvement contribute to legal entanglements that may uniquely disadvantage certain subgroups of the population (Harris 2016; U.S. Department of Justice 2015). Despite growing awareness of legal fines and fees and their implications, less attention has been paid to the socio-political foundations of the expansion and enforcement of fines and fees in an era of penal reform.

Compelling evidence shows that new forms of surveillance and punishment, including legal fines and fees, vary in important ways across and within states (Harris 2016; Harris, Evans, and Beckett 2010; Martin et al. 2018). However, differences in law and practice across jurisdictions make it difficult to fully account for, and thus explain, the prevalence and implications of non-custodial sanctions. In a review of statutes governing legal fines and fees in eight states, Martin and colleagues (2018) identify the ubiquity of statutes governing legal fines and fees across states but also draw attention to differences across states in the extent to which the statutes mandate their imposition for felony and misdemeanor cases, opportunities for waivers, and mechanisms of compliance. Work in Pennsylvania finds that offender and offense characteristics influence the likelihood of receiving fines and fees (Ruback and Clark 2011); work in Washington found that Latinos received harsher monetary sanctions than non-Latinos (Harris, Evans, and Beckett 2011), while work in California has found that the racial composition of both the population and law enforcement is associated with city reliance on fines and fees for revenue (Singla, Kirschner, and Stone 2019).

The assessment and enforcement of legal sanctions for misdemeanors presents an important and timely opportunity to re-examine the socio-political foundations of punishment. It is especially interesting to consider whether and how existing theoretical explanations for punishments such as the death penalty and incarceration are relevant because legal fines and fees, like mass misdemeanors and other forms of courtroom or community surveillance, are often viewed as alternatives to incarceration (Demleitner 2005; Thistlethwaite, Wooldredge, and Gibbs 1998). Nonetheless, as work by Kohler-Hausmann (2018), Lerman and Weaver (2014), Stewart and Uggen (2019), and others has shown, seemingly minor contacts with the criminal legal system can lead to protracted and extensive legal entanglements. Legal fines and fees particularly disadvantage people on the basis of ability to pay (Harris 2016). In fact, the Ferguson Commission Report concluded that legal financial obligations were exploitative and “disproportionately harmed defendants with low incomes” (Ferguson Commission 2015:93).

POLITICAL, RACIAL, AND ECONOMIC DETERMINANTS OF PUNISHMENT

Despite contemporary discourse heralding bi-partisan support for and colorblind approaches to criminal justice reforms, punishment in the United States has historically been understood as a product of political ideology, racial threat, and economic competition. Research has also drawn attention to how both legal and extralegal forms of punishment are fueled and sustained by organizational, institutional, and political forces (Campbell and Schoenfeld 2013; Hinton 2016; Tolnay, Deane, and Beck 1996). The specific contours of punishment differ across states and localities and in relation to racialized political and economic opportunity and conflict (Hinton 2016). Nonetheless, for much of its history the United States has waged a sustained campaign against both real and imagined acts of crime and violence with disproportionate impacts aligned with race and class cleavages that undergird economic, social, and political inequality (Travis, Western, and Redburn 2014; Western 2006).

Previous research has shown that the use of the death penalty and the size of the prison population are associated with political factors such as the strength of the Republican Party or public opinion about crime and punishment. Prior research has measured these constructs through the identification of party membership for key political positions such as the governorship, percent vote share in elections, or attitudes about punishment (Jacobs and Helms 1996; Western 2006). Historically, Republican politicians were more likely to support increased spending on crime control and penal expansion (cf. Hinton 2016). Jacobs and Helms (1996) demonstrate that party affiliation and party-specific policy initiatives have independent and significant effects on the number of prison admissions.

Other research shows that crime and punishment are important political wedge issues routinely invoked to characterize political aspirants as weak on crime (Beckett 1997; Caplow and Simon 1999; Chambliss 1994). Although initially a uniquely Republican political tactic, Democrats, nervous that they would lose white and independent support, have used similar rhetoric. As noted in the National Academy of Sciences review on the Causes and Consequences of Mass Incarceration across the United States, “The two parties embarked on periodic ‘bidding wars’ to ratchet up penalties for drugs and other offenses” (Travis et al. 2014:120). Texas was no exception. Crime and punishment has been a central theme of bipartisan Texas politics for at least the past 50 years (Campbell 2011).

Politics at the state level is a key determinant of criminal legal policies and practices because state statutes govern most criminal legal institutions within a state. As Jacobs and Carmichael put it, “state agencies have the most influence on correctional outcomes” (2001:64). Research has shown that states with governors who focus on crime control see greater increases in incarceration than neighboring states (Davey 1998). Smith (2004) found that “incarceration rates decreased by an average of seven prisoners per 100,000 population for every 1 percentage point increase in the number of Democratic legislators” (2004:934). Both Jacobs and Carmichael (2001) and Beckett and Western (2001) find evidence of a significant association between Republican legislative strength and increases in states’ imprisonment rates.

Thus theory and previous empirical research suggest that politically conservative jurisdictions should exhibit higher levels of punitiveness. However, it is not entirely clear whether or to what extent the relationship between conservative politics and punitiveness holds for seemingly less severe forms of punishment such as the assessment or enforcement of legal fines and fees for misdemeanor infractions. Given legal ambiguity surrounding fines and fees, it may be the case that political conservatism could lead to a greater number of, or more severe, fines and fees. Alternatively, and to the extent that legal fines and fees are viewed as a more compassionate – or less punitive – form of punishment, fines and fees could be associated with higher levels of political liberalism. This tension leads to the hypothesis that counties with more Republican voters will both assess and collect more fines and fees. Alternatively, counties with more Democratic voters may embrace LFOs as an alternative to imprisonment, generating the hypothesis that counties with more Republican voters will both assess and collect fewer fines and fees.

Another key explanation for the rise in incarceration and other forms of punishment has been linked to racial threat. For decades political strategies and rhetoric have appealed to racial anxieties to rally support for law and order policies and to increase incarceration (Beckett 1997; Travis, Western, and Redburn 2014). Recent research has emphasized how racial politics nurtured the development of the U.S. carceral state and undergirds its continued operation (Hinton 2016; Schoenfeld 2018). Schoenfeld advances a detailed account of how racial projects, or “purposeful actions in response to ongoing racial dynamics” led to “policy preferences to expand carceral capacity” (2018:14) in Florida through the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century.

On an aggregate level, research shows a consistent relationship between measures of racial threat and severe criminal justice outcomes (Keen and Jacobs 2009; Liska, Chamlin, and Reed 1985; Olzak and Shanahan 2014; Stolzenberg, D’Alessio, and Eitle 2013). Cities with higher Black populations have more police per capita (Jacobs 1998) and higher levels of fear of crime (Quillian and Pager 2001). Jurisdictions with higher proportions of Black and Latinx residents are subject to greater surveillance, policing, and arrest than other jurisdictions (Kohler-Hausmann 2018; Stuart 2016). Racialized surveillance and policing have contributed to significant racial gaps in exposure to the criminal legal system at every level (Weaver, Papachristos, and Zanger-Tishler 2019). By 2002, around 12 percent of Black men in their twenties were in prison or jail (Harrison and Karberg 2003) and among young Black men without a high school diploma, incarceration had become a dominant experience in the life course (Pettit and Sykes 2015; Pettit and Western 2004). Latinx populations are incarcerated disproportionally as well; Latinx residents make up 22 percent of the prison population, while making up only 17 percent of the overall population (Kaeble and Cowhig 2016).

A growing body of research has drawn attention to the complexity of the role of race and ethnicity in the U.S. criminal legal system, and there are important reasons to think that in some jurisdictions ethnic conflict may be an important determinant of punitiveness. The concept of ethnic threat may be especially salient in Texas, given its large Latinx population and history as an immigrant destination. Increased attention to immigration may lead to new racial anxieties around the Latinx population. Recent scholarship, for example, has demonstrated that Latinx population growth is correlated with more regressive state and local tax policies (O’Brien 2017).

Research in New York shows that people living in disproportionately Latinx neighborhoods are subject to high arrest rates (Kohler-Hausmann 2018), and evidence from Washington indicates Latinx criminal defendants receive disproportionately high monetary sanctions (Harris, Evans, and Beckett 2010). Latinx defendants also receive longer prison sentences than either whites or Blacks (Demuth 2003; Schlesinger 2005).

Previous theory and research highlighting the relevance of racial and ethnic conflict for punitive policies and racial and ethnic disproportionality in justice involvement leads us to expect that these constructs may also be relevant for the assessment and enforcement of legal fines and fees. Insights from literature showing greater exposure to policing (Rios 2011; Wacquant 2009), higher arrest rates (Blumstein 1993), and unequal sentencing (Tonry 1995) lead to the expectation that communities with large, or growing, fractions of Black or Latinx residents should also be subject to disproportionately high assessment and collection of LFOs. Alternatively, counties with larger and more rapidly growing Black and Latinx populations may view LFOs as a less punitive alternative punishment, generating the hypothesis that counties with more – or more rapidly growing numbers of – Black and Latinx residents will both assess and collect fewer fines and fees and favor more incarceration or other types of punishment.

Decades of research have now documented the centrality of the criminal legal system for accounts of inequality (Kirk and Wakefield 2018; Turney and Wakefield 2019; Wakefield and Uggen 2010; Western 2006). The criminal legal system disproportionately infiltrates the lives of people who are poor, live in poor neighborhoods, and have limited financial capacity to elude the “long arm” of the law. Theoretical work emphasizes how the criminal legal system is one of control: managing marginality, controlling surplus labor, maintaining order and “decorum” (Wacquant 2009; Western 2006). Related empirical work highlights how the criminal legal system has replaced welfarist programs for the most disadvantaged segments of the population and how its growth aligns with declines in other welfare state provisions (Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011). These ideas suggest that poverty should be a cause or correlate of punitiveness as well. Legal financial obligations, or monetary sanctions, may uniquely impact people who are poor. Katzenstein and Waller describe monetary sanctions as an inverted welfare system that “taxes poor families to help fund the state’s project of poverty governance” (2015:639).

Existing literature on other forms of punishment offers mixed support for the relationship between economic factors and punishment. Studies have found a relationship between unemployment and prison growth (Chiricos and Delone 1992; Meyers and Inverarity 1992), but other studies have found no relationship between unemployment and prison growth when accounting for political and racial factors (Helms and Jacobs 2002; Sutton 2004). Results on the relationship between economic inequality and punishment have been equally mixed: some evidence shows states and cities with higher levels of inequality imprison higher percentages of their populations (Jacobs 1978; Liska, Chamlin, and Reed 1985), while other evidence does not support such claims (Jacobs and Carmichael 2001).

How legal fines and fees, or monetary sanctions, are conceptualized suggests a couple of alternative expectations for their relationship with poverty or as a mechanism of poverty governance. On the one hand, jurisdictions with higher levels of poverty may assess and collect fewer fines and fees, choosing instead to prioritize sanctions like incarceration or other types of punishments over monetary sanctions. On the other hand, jurisdictions with higher levels of poverty or economic inequality may actively assess and collect LFOs in ways that widen the net of criminal legal involvement or enhance legal entanglements for those unable to pay.

Poverty and economic inequality may also be correlated with the assessment and collection of LFOs for other reasons. Decades of criminal legal expansions have generated significant budget short-falls and the state is continually exploring ways to fund the system (Weber 2016). Texas has no state income tax and fines and fees have been consistently identified as a mechanism to generate revenue to fund legal operations; the collection of probation and parole fees fund approximately 35 percent of local probation costs (Texas Department of Criminal Justice 2018) and collection of misdemeanor fines and fees remains the number one source of revenue for local jurisdictions (Whitson 2015).

The United States Department of Justice identified the extractive nature of fines and fees in its 2015 report on Ferguson noting that “the municipal court does not act as a neutral arbiter of the law or a check on unlawful police conduct. Instead, the court primarily uses its judicial authority as the means to compel the payment of fines and fees that advance the City’s financial interests” (2015:3). Taggart and Campbell (2015) found that in one city in Texas “fines for traffic and other low-level offenses brought in more than $11 million in each of the past three years — nearly 4 percent of the city’s general fund revenue” (Taggart and Campbell 2015). Research on monetary sanctions in Nevada and Iowa demonstrates that reliance on fines and fees for revenue creates continuous criminal justice contact (Martin 2018). Related research finds that law enforcement increase their drug seizure activities when they are tied to revenue generation (Baicker and Jacobson 2007; Holcomb, Kovandzic, and Williams 2011), and more tickets are issued in the year following a decline in revenue (Garrett and Wagner 2009). These observations lead to the expectation that alongside the implications of aggregate levels of poverty and economic inequality, counties facing higher budget deficits will assess and collect more fines and fees.

DATA, MEASURES, AND METHODS

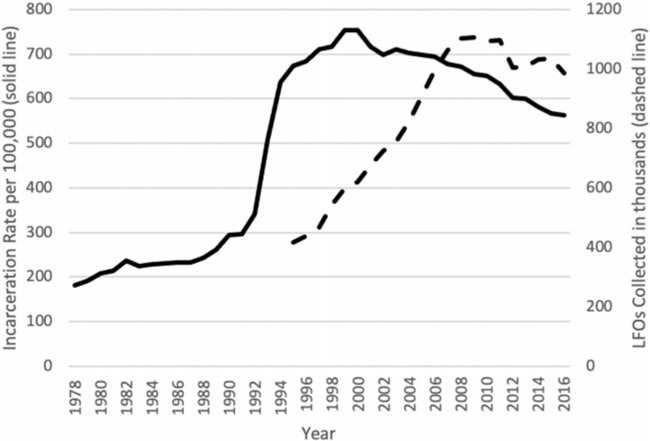

In order to investigate the factors associated with the expansion and enforcement of legal financial obligations (LFOs), we use county level data from Texas, a large and historically punitive state that is “leading the way in much needed criminal justice reform” (Washington Post 2014). Texas is a particularly interesting case for several reasons. The collection of fines, fees, and court costs in Texas Class C misdemeanor courts represents the amount of money that courts receive from defendants. The amount of money collected has increased dramatically over the past 20 years from around $700 million to over $1.2 billion by 2014, hovering over one billion dollars in the years since (Texas Office of Court Administration 2018). Furthermore, LFOs are assessed at every level of the court system and, as Figure 1 shows, collection for low-level misdemeanors grew in conjunction with the number of people in prison or jail until about 2000. Statewide, we observe increases in the collection of fines and fees coinciding with decreases in incarceration rates. This context encourages us to investigate whether there is a trade-off. However, county level analysis suggests that the same determinants of higher levels of incarceration are also associated with proportionately higher fines and fees. We interpret this to mean that fines and fees are an additional tool for punishment disproportionately deployed by politically conservative counties and those with comparatively large minority populations.

Figure 1. Texas Incarceration Rate and LFOs Collected 1978–2016.

Sources: Texas Office of Court Administration (2018), Texas Department of Criminal Justice (2016)

Monetary sanctions are assessed at every level of the judiciary in Texas (Martin et al. 2018). However, legal debt – and thus collections as the primary source of punishment – is concentrated at the misdemeanor level in Texas and other states where work on monetary sanctions has occurred (Martin 2018). Felony level courts in Texas disposed of nearly 300,000 cases in 2016, but only 256 of those cases involved only a fine (Texas Office of Court Administration 2018). Class C Misdemeanor courts also feature by far the largest caseloads, disposing of nearly 7 million cases in 2016. Thus, we focus our empirical attention on the collection of LFOs for Class C misdemeanor, or non-jailable, offense types. Focusing on offenses where a harsher form of punishment such as incarceration is not an option allows us to examine the collection of fines and fees as an independent event rather than as an addition to jail or prison sentences. Notably, custodial sanctions also include fines and fees, though they are typically satisfied by time served.

Data on legal fines and fees assessed and collected for Class C, or non-jailable, misdemeanor offense types at the local level are reported to, and maintained by, the Texas Office of Court Administration (2018). Data on assessments are not systematically reported across jurisdictions, though data on collections are reported, at least annually, by over 1,000 Municipal and Justice of the Peace courts across the state. We aggregate these data to the county level to construct a measure of the dollar amount of legal fines and fees collected for Class C misdemeanors at the county level, by year. Our resulting data thus include measures of collections from 254 counties across the state through 2016, the last year for which data are available.

Legal financial obligations (LFOs) include court costs, fees, fines, restitution orders, and other financial obligations that may be imposed by the courts and other criminal justice agencies on persons accused of crimes. Fines are typically considered punishments and costs and fees are set by the legislature and are associated with use of the court system (Slayton 2014). In the OCA data, these have been bundled together into the amounts collected by each county. The combination of fines with court costs and fees has important implications. Because costs are set by the legislature, they are standard across the state. Therefore, the differences in the amounts collected per case are at least partially the result of discretionary decisions made on fine levels by the courts themselves. For example, for most traffic offenses, the scheduled court cost is $108 (Slayton 2014). Everything collected in addition to the $108 would be based on the discretionary fine amount. Courts that collect more per case are, therefore, either setting higher fine amounts or collecting a higher percentage of the LFOs that are assessed. Because OCA data do not include systematically collected information on assessment, it is not possible to distinguish differences in assessments from differences in enforcement. However, we maintain that observed variation in collections reveals important information about the socio-political environment that undergirds the rise and enforcement of LFOs. Collections reflect the amount of financial resources that are directly transferred from legal defendants to the court and, therefore, are an accurate reflection of monetary sanctions as a form of punishment, whether this punishment occurs through higher fine amounts or a more extensive collection apparatus.

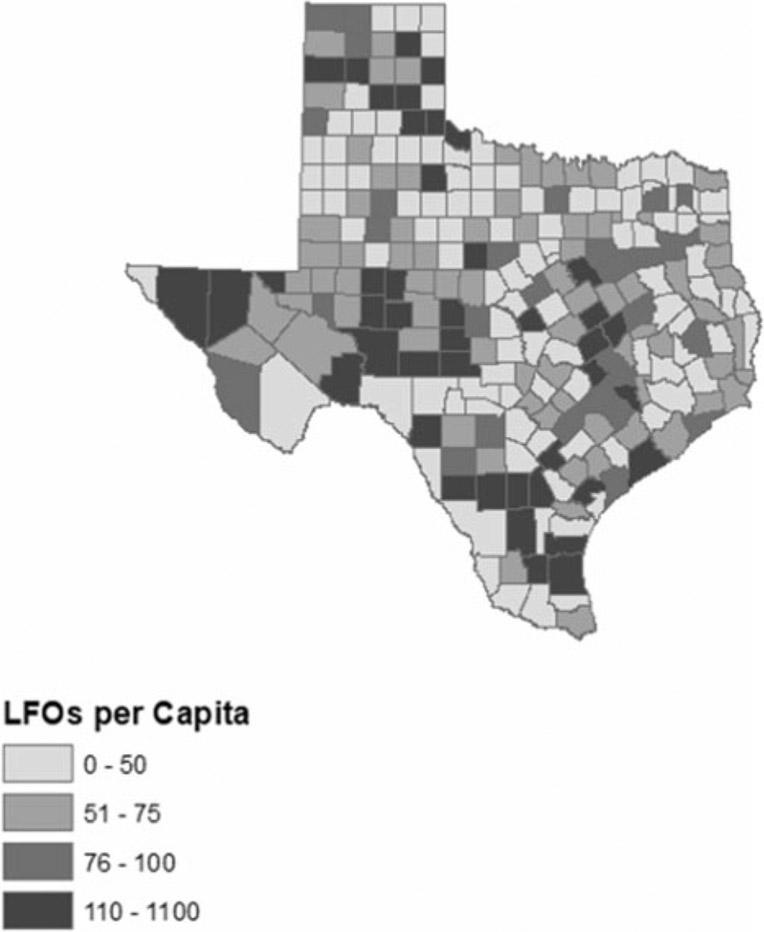

Our key dependent variable is a measure of misdemeanor LFO collections adjusted for total population size, or LFOs per capita. Texas counties vary greatly in population size and our estimates suggest that in 2016 the smallest county was 115 people (Loving), while the largest was over 4.6 million people (Harris).2 Figure 2 maps the variability in LFO collections per capita across Texas. The map illustrates that, in broad strokes, per capita collections for low-level misdemeanors (Class C) are lowest in northeast Texas, while collections are highest in sparsely populated and border areas of northern Texas, or the Panhandle, as well as western and southern counties in Texas.

Figure 2. Legal Fines and Fees Collected in Texas, By County, 2016.

Table 1 provides basic descriptive information about per capita LFOs, as well as other variables of interest, in 254 Texas counties in 2016. County-level per capita LFO collections averaged $86 in 2016. A closer look shows that county-level collections varied from just over $11 per capita in Hansford, a county in the Panhandle bordering Oklahoma, to $1,147 in Kenedy, a sparsely populated county in southern Texas on the Gulf of Mexico. Loving, the least populated county in Texas and one that borders New Mexico, had the second highest per capita collections in 2016, bringing in $1,040 per resident. Total LFO collections in highly populated counties of Harris, Dallas, Tarrant, Bexar, and Travis dwarfed collections in all other parts of the state. However, adjusted for population size, collections in those counties ranged from $40–$70 per resident, well below the average for all counties in the state. We also constructed measures of LFO collections per case and misdemeanor cases per capita, which averaged $225 and .44, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics Texas Counties, 2016

| Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFO per Case | 225.65 | 55.76 | 77.49 | 502.34 |

| LFO per Capita | 86.79 | 126.11 | 11.06 | 1147.17 |

| LFO Cases per Capita | 0.44 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 13.12 |

| Percent Republican Vote | 71.78 | 16.33 | 18.94 | 94.58 |

| Percent Black | 6.28 | 6.60 | 0.00 | 34.23 |

| Percent Latinx | 34.98 | 23.09 | 2.19 | 97.52 |

| Black Percent Change (1yr) | −0.27 | 3.78 | −27.58 | 6.67 |

| Latinx Percent Change (1yr) | 1.79 | 1.22 | −4.37 | 4.63 |

| Debt per Capita ($) | 2,035 | 17,177 | 2 | 222,090 |

| Mean Income ($) | 26,151 | 6,192 | 13,050 | 53,367 |

| Poverty Rate | 16.7 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 42.7 |

| Unemployment Rate | 7.5 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 24.9 |

| Police per 10,000* | 14.5 | 28.6 | 0.0 | 347.8 |

| Crime per 1,000 | 14.7 | 15.3 | 0.0 | 191.3 |

| Incarceration per 100,000* | 651.6 | 360.8 | 0.0 | 3738.3 |

| Population Size | 109862.0 | 397087.0 | 115.0 | 4617041.0 |

| N= 254 Counties | ||||

Data were interpolated for missing years.

To capture the influence of politics, we rely on voting data provided by the Texas Secretary of State (2019). Texas has the reputation of being a largely Republican state, and statewide elections have routinely produced Republican majorities for the last few decades.3 There is important variation in Republican vote share, however, across counties. Although the mean percentage Republican presidential vote at the county level was 71 percent in 2012, and one county had 96 percent of voters cast a ballot for the Republican presidential candidate, 27 counties had Republican vote shares of less than 50 percent. The Democratic-leaning counties in Texas include four of the largest five most populous counties in the state. Data from 2016 show higher levels of Democratic support in many counties in Texas but especially in highly populous and racially and ethnically diverse counties (Esdall 2018).

To measure the concepts of racial and ethnic threat, we rely on indicators of racial composition and change at the county level reported by or constructed from Census data. We use Census data collected in 2000 and 2010, along with data on population growth as estimated by the Population Division of the U.S. Census Bureau (2019), to estimate the percent of the resident population that self-reports as Black and Latinx as well as a measure of annual percent change in Black and Latinx populations.4 We assume a constant rate of change in the racial and ethnic composition within counties after 2010. We test the sensitivity of our results to alternative estimation strategies for these and other constructed measures. Since Texas is formerly part of Mexico, it is perhaps no surprise that many Texas counties have a higher fraction of Latinx residents than Black residents. We estimate that by 2016 Texas counties had, on average, 6.3 percent of residents who self-identified as Black and 35 percent of residents who self-identified as Latinx. Our estimates suggest that, on average, counties were experiencing small Black population declines (.3 percent per year), while experiencing somewhat larger Latinx population increases (1.8 percent per year).

To measure economic conditions likely associated with the assessment and collection of LFOs, we include data on mean income, poverty rates, and unemployment rates. Again, we begin with data provided by the Census for census years 2000 and 2010 and estimate quantities for years after 2010 assuming constant rates of change within counties (Gann et al. 2017). Table 1 shows that in 2016, counties had an average mean income of $26,151; county poverty rates averaged 16.7; and county unemployment rates averaged 7.5 percent. We test the sensitivity of our results to different methods of estimating data for intercensal years and we replicate results for 2016 (shown here) with data from 2010 where we have relied on measures directly produced by the Census.

We also include measures of the number of law enforcement personnel, the crime rate, the incarceration rate, county debt, and total population size. Data on law enforcement personnel come from the Texas Department of Public Safety (2019). By 2016, on average, counties employed 14.5 police officers per ten thousand residents. The number of officers ranged from 0 in Henderson and Cottle counties to 357 in Loving County, per ten thousand residents. The most highly populous counties had relatively few officers per ten thousand residents while sparsely populated counties, like Loving and Kenedy, had comparatively many officers per capita. As may be increasingly clear, much of the variability in this and other county-level measures is attributable to overall population size and thus we pay careful attention to the sensitivity of results to outlying and potentially influential cases (counties). Data on crime rates come from the Texas Department of Public Safety UCR program (2016). The mean crime rate, including all index crimes, was 14.6 offenses per 1,000 residents. Data on incarceration rates come from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (2016). County-level incarceration rates averaged 651 per 100,000. Debt data from the Texas Bond Review Board (2018) show that county debt averaged $1,337 per capita. Seventy-nine counties had no reported debt in 2016 and four counties, including Harris County, had debt in excess of $1 billion.

We analyze these data using regression methods, including those designed to address the impact of outlying and potentially influential cases. We begin by showing the results from OLS regression on LFO collections per capita in 2016. After conducting a range of diagnostics that suggest alternative modeling specifications, we re-estimate models using the log transformation of LFO collections per capita in 2016. We further explore the sensitivity of results using robust standard errors and high breakdown estimators including M-estimators (Huber 1973) and MM-estimators (Yohai 1987). Finally, we analyze pooled cross-sectional data from 2010–2016, again using OLS with robust standard errors and high breakdown estimators to examine whether and how results vary by year.

RESULTS

By 2016, justice and municipal courts across the state of Texas collected over $1 billion annually in legal fines and fees for Class C, non-jailable, misdemeanor charges. Initial results show that “law and order” politics associated with Republican Party dominance and large police presence are routinely correlated with higher LFO collections across counties. Collections are inversely correlated with overall crime rates, which contradicts the notion that high rates of crime are generating higher exposure to, or collections from, LFOs. Further analyses show that LFO collections are also disproportionately concentrated in counties with larger fractions of Black and Latinx residents. Thus, and although LFOs may represent an alternative to custodial sanctions such as prison and jail time, their concentration and socio-political foundations are remarkably similar to those predictive of other forms of punishment.

Table 2 shows results from an OLS regression of LFOs collected per capita on political, racial and ethnic, economic, and other factors we expected to be important determinants. Politically conservative counties collect more fines and fees per capita than counties with greater percentages of Democratic voters. The far right column in Table 2 shows that the percent of Republican voters in a county is positively and significantly associated with collections. Results also indicate that the size of the police force is positively correlated with collections. In contrast, the crime rate is negatively associated with collections. Although results indicate that county level debt has a positive and significant relationship with collections, further analysis does not withstand further scrutiny.5

Table 2.

OLS Regression on LFOs Per Capita in Texas Counties, 2016

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Republican | 0.223 (0.486) | 1.241 (0.505)* | |||

| Percent Black | −1.940 (1.298) | 1.755 (0.934) | |||

| Percent Latinx | 0.391 (0.419) | 0.764 (0.381)* | |||

| Black Pop Growth | 4.178 (2.095)* | 1.670 (1.209) | |||

| Latinx Pop Growth | −3.649 (7.727) | −6.548 (4.500) | |||

| Debt per Capita | 0.005 (0.000)** | −0.001 (0.001)** | |||

| Mean Income | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | |||

| Poverty Rate | 1.517 (1.211) | 0.190 (0.825) | |||

| Unemployment Rate | −6.550 (1.773)** | −0.674 (1.247) | |||

| Police | 4.091 (0.245)** | 4.375 (0.300)** | |||

| Crime Rate | −1.387 (0.457)** | −0.735 (0.492) | |||

| Incarceration Rate | 0.032 (0.013)* | 0.015 (0.014) | |||

| Population | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |||

| Constant | 70.768 (35.787)* | 92.916 (27.445)** | 139.776 (52.541)** | 27.279 (10.992)* | −71.964 (71.356) |

| R2 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.69 | 0.72 |

| N | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 |

p<0.05

p<0.01; Two-tailed tests.

Taken together, these results suggest that conventional predictors of punitiveness including conservative politics and investments in policing are similarly associated with the collection of legal fines and fees for low-level misdemeanors in Texas. In contrast to theoretical ideas that suggest misdemeanors, or associated LFOs, may be a substitute for more intensive forms of punishment, these results suggest that they are complementary. Punitive counties exact higher levels of monetary sanctions just as they imprison a higher fraction of their population. Importantly, there is no evidence that these counties exhibit higher crime rates than those who exhibit lower overall levels of punishment.

Texas is a large and diverse state with one of the most populous counties in the United States (Harris) and one of the least populous counties (Loving). County lines represent important political boundaries for studies of jurisprudence and the criminal legal system in Texas and provide a convenient unit of analysis from a measurement standpoint. However, careful review of measures of model fit and potentially outlying and influential cases, including but not limited to Harris and Loving counties, led us to conduct a series of additional analyses to further interrogate the robustness of our results. For example, our results along with careful interrogation of specific counties suggest that some small counties appear to use legal fines and fees as a key source of revenue. In counties with an interstate highway, we see well above average collections. In counties with high transient labor populations, we also observe well above average collections. In addition, we conducted further supplemental analyses to examine the effects of county size for our results and their implications. We performed analyses excluding the 10 smallest counties and results remained consistent.

As a result of these investigations and potential violations of assumptions of OLS regression methods, we analyze the impact of political, racial and ethnic, economic, and other relevant characteristics on the log transformation of LFOs in Table 3. Results in Table 3, though generally consistent with those presented in Table 2, offer a few additional insights. Most notably, the log of LFO collections is positively associated with the percentage of residents who are Black and the percentage of residents who are Latinx. Republican vote share and the size of the police force continue to be positively associated with the log of LFO collections and the crime rate is negatively associated with the log of LFO collections. These results provide further evidence that political indicators are salient for LFOs in much the same way that they help explain variation in arguably more punitive forms of punishment like incarceration rates. However, these results also show that racial and ethnic demographics of a county are also important determinants of the assessment and enforcement of legal fines and fees at the misdemeanor level. Although we are unable to identify the specific individuals subject to legal fines and fees, these results are consistent with recent work showing the concentration of misdemeanor arrests in disproportionately Black and Latinx neighborhoods in places like New York City (Fagan et al. 2016; Kohler-Hausmann 2018).

Table 3.

OLS Regression on Log of LFOs Per Capita in Texas Counties, 2016

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Republican | 0.001 (0.003) | 0.012 (0.005)** | |||

| Percent Black | −0.004 (0.008) | 0.022 (0.009)* | |||

| Percent Latinx | 0.004 (0.002) | 0.012 (0.003)** | |||

| Black Pop Growth | 0.028 (0.012)* | 0.017 (0.011) | |||

| Latinx Pop Growth | −0.002 (0.045) | −0.023 (0.041) | |||

| Debt per Capita | 0.000 (0.000)** | −0.000 (0.000) | |||

| Mean Income | −0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |||

| Poverty Rate | 0.003 (0.008) | −0.001 (0.008) | |||

| Unemployment Rate | −0.028 (0.012)* | 0.003 (0.011) | |||

| Police | 0.017 (0.002)** | 0.017 (0.003)** | |||

| Crime Rate | −0.013 (0.004)** | −0.011 (0.004)* | |||

| Incarceration Rate | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |||

| Population | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | |||

| Constant | 4.025 (0.209)** | 4.001 (0.161)** | 4.276 (0.348)** | 3.977 (0.099)** | 2.195 (0.652)** |

| R2 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.31 |

| N | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 |

p<0.05

p<0.01; Two-tailed tests.

Table 4 further tests the sensitivity of these results to alternative modeling specifications including models that estimate robust standard errors and those that employ high breakdown estimators. We also examined how results changed with the exclusion of particularly influential cases and found them substantively consistent with those presented here. Results generally confirm those in Table 3: higher fractions of Republican voters, higher percentages of Black and Latinx residents, and proportionately larger police forces are consistently and positively associated with the collection of legal fines and fees. Counties with higher crime rates, measured by all index crimes, observe lower collections of LFOs. These relationships are robust to a wide variety of modeling specifications and in the context of a large and diverse state with counties that range dramatically in size and composition.

Table 4.

Regression on Log of LFOs Per Capita in Texas Counties, 2016, Robust Estimators

| OLS | Robust | M-estimator | MM-estimator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Republican | 0.012 (0.005)** | 0.012 (0.005)* | 0.013 (0.006)* | 0.011 (0.007) |

| Percent Black | 0.022 (0.009)* | 0.022 (0.008)** | 0.020 (0.008)* | 0.015 (0.009) |

| Percent Latinx | 0.012 (0.003)** | 0.012 (0.004)** | 0.013 (0.004)** | 0.010 (0.004)* |

| Black Pop Growth | 0.017 (0.011) | 0.017 (0.014) | 0.015 (0.017) | 0.019 (0.032) |

| Latinx Pop Growth | −0.023 (0.041) | −0.023 (0.059) | 0.021 (0.073) | 0.029 (0.096) |

| Debt per Capita | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Mean Income | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Poverty Rate | −0.001 (0.008) | −0.001 (0.008) | −0.002 (0.008) | −0.000 (0.009) |

| Unemployment Rate | 0.003 (0.011) | 0.003 (0.015) | 0.007 (0.020) | 0.010 (0.026) |

| Police | 0.017 (0.003)** | 0.017 (0.004)** | 0.017 (0.004)** | 0.027 (0.006)** |

| Crime Rate | −0.011 (0.004)* | −0.011 (0.005) | −0.013 (0.007) | −0.013 (0.008) |

| Incarceration Rate | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Population | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Constant | 2.195 (0.652)** | 2.195 (0.658)** | 2.000 (0.729)** | 2.208 (0.812)** |

| R2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | ||

| N | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 |

p<0.05

p<0.01; Two-tailed tests.

Table 5 shows results from analyses of pooled data from 2010-2016 which are again consistent with those presented in earlier tables. Republican Party strength, racial and ethnic composition, size of the police force, and crime rates are statistically significantly related to the log of per capita collections of LFOs for low level misdemeanors. Mean income has a small, but statistically significant, positive effect on collections. Overall population size is inversely associated with the per capita collection of LFOs. At the same time, Latinx population change seems to have mixed effects on collections, positive in some estimations but negative in others. There is little evidence that either collections, or the factors associated with them, at the county level vary dramatically over this seven-year period. The high water mark for collections adjusted for other factors was 2013 although aggregated data suggest 2014 brought in the highest total of LFOs to the state.

Table 5.

Regression on Log of LFOs Per Capita in Texas Counties, 2010-2016

| OLS | Robust | M-estimator | MM-estimator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Republican | 0.013 (0.002)** | 0.011 (0.002)** | 0.010 (0.002)** | −0.006 (0.007) |

| Percent Black | 0.017 (0.003)** | 0.017 (0.003)** | 0.016 (0.003)** | 0.022 (0.041) |

| Percent Latinx | 0.008 (0.001)** | 0.009 (0.001)** | 0.009 (0.001)** | −0.011 (0.018) |

| Black Pop Growth | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.003) | −0.005 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.001) |

| Latinx Pop Growth | −0.069 (0.018)** | 0.004 (0.016) | 0.034 (0.013)** | −0.143 (0.088) |

| Debt per Capita | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000)* | −0.000 (0.000)** | 0.000 (0.000)* |

| Mean Income | 0.000 (0.000)** | 0.000 (0.000)** | 0.000 (0.000)** | −0.000 (0.000) |

| Poverty Rate | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | −0.007 (0.016) |

| Unemployment Rate | −0.007 (0.007) | 0.002 (0.007) | 0.002 (0.007) | −0.044 (0.020)* |

| Police | 0.013 (0.002)** | 0.015 (0.001)** | 0.015 (0.001)** | 0.003 (0.002) |

| Crime Rate | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.008 (0.002)** | −0.009 (0.002)** | 0.001 (0.002) |

| Incarceration Rate | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Population | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000)* | −0.000 (0.000)* | 0.000 (0.000) |

| 2010 | 0.002 (0.060) | 0.000 (0.055) | −0.020 (0.053) | −0.270 (0.099)** |

| 2011 | 0.024 (0.057) | 0.015 (0.054) | 0.008 (0.052) | −0.219 (0.084)** |

| 2012 | −0.033 (0.058) | −0.060 (0.052) | −0.079 (0.050) | −0.240 (0.069)** |

| 2013 | 0.151 (0.058)** | 0.150 (0.053)** | 0.143 (0.050)** | −0.013 (0.052) |

| 2014 | 0.100 (0.056) | 0.091 (0.051) | 0.093 (0.049) | −0.003 (0.035) |

| 2015 | 0.042 (0.057) | 0.016 (0.051) | 0.015 (0.050) | −0.012 (0.022) |

| Constant | 2.343 (0.255)** | 2.173 (0.250)** | 2.171 (0.253)** | 5.950 (1.263)** |

| R2 | 0.28 | 0.18 | ||

| N | 1,778 | 1,778 | 1,778 | 1,778 |

p<0.05

p<0.01; Two-tailed tests.

To illustrate these results we considered a counterfactual scenario in which we generated predicted LFO collections per capita assuming collections across the state were equivalent to those found in the least punitive county. This thought experiment allows us to answer the question: what would LFO collections be if all counties in the state pursued collections to the same extent as those in the least punitive county (Hansford) where collections averaged just over $11 per capita in 2016? The result, of course, would be significantly lower collections statewide. Collections in Hansford were 87 percent less, per capita, than average. But because the largest and most populous counties have low levels of collections per capita relative to the mean across counties, total collections in this scenario would be approximately one fifth as large as those collected in 2016, or just over 300 million dollars.

Quite a different scenario would result if counties pursued collections consistent with those that prevail in the most punitive county measured by per capita LFO collections. Kenedy County, a sparsely populated county on the Gulf of Mexico, collected $1,147 per capita in LFOs in 2016. Collections in Kenedy were 13 times more than the average of per capita collections by county. Yet, if every county collected LFOs at the same rate as Kenedy, statewide collections would increase more than 20-fold because some of the most populous counties collect significantly less than the state average.

These relatively simple scenarios help to illustrate the variability in LFO collections across counties and help to show that LFO collections are disproportionately concentrated in relatively sparsely populated counties. Our regression results are consistent with these insights and also draw attention to political conservatism, policing, and other measures of punitiveness. To be clear, these are hypothetical scenarios in which we simply consider how uniform levels of punitiveness, measured by per capita collections, would affect overall collections. These scenarios adjust only for population size and do not consider how variability aligns with political representation, racial and ethnic composition, policing, or other measures. These results, however, indicate that LFOs are used disproportionately by small or sparsely populated jurisdictions, to discipline and punish alleged lawbreakers. Thus, and while much attention has been drawn to the use and consequence of LFOs in large urban or suburban jurisdictions, like Ferguson, Missouri, or El Paso, Texas, they may be an equally if not more important feature of the punishment landscape in rural jurisdictions.

Finally, jurisdictions also report annually the number of cases satisfied in full by community service, satisfied in part by community service, satisfied by jail credit, receiving an indigency waiver, and the amount of collections waived. The data have been collected consistently from 2012–2016. We imputed data for 2010 and 2011 based on percentages from 2012. There is widespread variation in the use of alternative sanctions across counties. Data from 2016 show that, on average, 0.3 percent of cases are satisfied in part by community service; 1.3 percent of cases are satisfied in full by community service; 8.8 percent of cases are satisfied by jail credit; 0.5 percent of cases receive an indigency waiver; and 0.5 percent of total collections are waived (See Appendix Table 2). However, the use of alternative sanctions varies dramatically across counties. Very few counties report that many cases are satisfied in part by community service. Nine counties report 5–10 percent of cases satisfied in full by community service. More than a quarter of cases are satisfied by jail credit in 17 counties. Similarly, counties consistently waive a very small percentage of the total amount collected. All but one county waives less than five percent of total collected.

Many of the same factors that predict total collections also predict the use of alternative sanctions (See Appendix Tables 3-4). However, there is at least one key difference. A higher fraction of Republican voters is negatively associated with the use of community service. Proportionately larger Black and Latinx populations, Latinx population growth, debt, and incarceration rates are positively and significantly associated with the use of jail credit. None of the observed measures is significantly related with granting indigency waivers, with the exception of the poverty rate in one specification. Similarly, only the poverty rate is significantly, and positively, associated with the amount waived.

In summary, these analyses suggest that alternative sanctions are not equivalencies with collections. Community service arrangements – both full and in part – are less likely to be used in counties with higher fractions of Republican voters. In contrast, the use of jail as a sanction – either as a credit for time served or (until recently) an offered alternative for payment – is more common in disproportionately minority counties. We cannot discern the motives of the prevalence of these different sanctions, but the results suggest that like collections, alternative sanctions are an important form of punishment.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Coinciding with literature on the political determinants of punitiveness in the criminal legal system, results in this paper show a consistent and positive relationship between Republican Party strength, measured by vote share, and legal fines and fees collected for non-jailable misdemeanors in Texas. At the same time, and in line with arguments that emphasize how the rise of incarceration and other dimensions of punitive jurisprudence result from racialized projects, results show the collection of legal fines and fees is consistently and positively correlated with the percentage of the population that is Black and Latinx. Results presented in this paper, however, suggest that LFOs are not simply a response to heightened crime rates or criminal activity but may be better understood as the consequence of large and presumably active police forces hewing to the enforcement of law and order even as crime rates decline (Texas Department of Public Safety 2016) and political demands for greater punitiveness have waned (Enns 2016).

These results have important theoretical and methodological implications. Contrary to conceptions of legal fines and fees as an alternative to harsher criminal justice sanctions, this paper demonstrates that the collection of monetary sanctions for low-level misdemeanors is an additional tool of punishment at the disposal of criminal justice actors. The assessment and enforcement of legal fines and fees for misdemeanors in Texas are largely explained by the same socio-political factors – conservative politics and racial threat – that have been influential for understanding the growth of mass incarceration and the exercise of the death penalty as well as the distribution of those types of punishment across jurisdictions. The same communities that have historically been subjected to a greater likelihood of and more time behind bars also face heightened surveillance and exposure to criminal legal sanctions including legal financial obligations. In sum, this research expands the literature on monetary sanctions to focus attention on the scope and determinants of LFOs for minor misdemeanors. In addition, we contribute to this emerging literature by putting it in dialogue with literature on the determinants of other forms of punishment and examining the social and political underpinnings of this large and growing system.

This study has important methodological strengths and weaknesses that offer valuable directions for future research. Texas is a large and diverse state that allows for a careful examination of how unified state laws governing misdemeanor fines and fees play out differently across jurisdictions. Variability in the collection of LFOs across jurisdictions is inconsistent with rational accounts of jurisprudence or those that rely on accounts of individual responsibility. There is little evidence that the overall level of LFOs is linked to crime rates or criminal activity, for example. Instead, our results are consistent with recent research that suggests that political and racial factors affect surveillance and thus the chances of receiving a citation, the severity of the sanction, and the enforcement of a sanction (Baumgartner, Epp, and Shoub 2018).

One limitation of this study is the fact that the data include results only from low-level Class C misdemeanors. Data from Class A and B misdemeanors may tell a different story. However, in almost all cases, those sanctions are effectively symbolic and wholly satisfied by time served in prison or jail. Thus, there is virtually no variability across the state in any measurable collections for serious misdemeanor or felony legal financial obligations. Therefore, we believe that Class C misdemeanors are best suited to test the hypothesis. Secondly, although we do not find evidence of a relationship between debt and collection of LFOs, it is an important area for future research. Texas does not collect state income tax and fines and fees may be a way of avoiding the direct imposition of new taxes. This may be particularly acute in counties with a low tax base dominated by conservative political elites. Future research could more carefully examine these and related questions. Finally, another limitation is the lack of data on restitution. Although restitution is an important element of the system of fines and fees, restitution is not directly identified in our data, and, therefore, we cannot examine it independently in our analysis. However, consistent with Harris, Evans, and Beckett (2011), we would anticipate that restitution operates under a different logic from other monetary sanctions because there is an identifiable victim who has suffered a financial loss.

Furthermore, it is hard to know whether and how results from this study generalize to other states or other jurisdictions. Texas is an outlier in many ways and we rely on data and measures at the county level which conceal significant variability in exposure to the criminal legal system and its consequences. However, Texas has attracted widespread attention for its efforts at criminal legal reform (Chettiar et al. 2015; Dunklee and Larsen 2015). Politicians and policymakers within and outside the state are making strong claims that the state has moved toward a less punitive, more fiscally responsible, and – in some quarters – more humane justice system (Chettiar et al 2015). These results raise important questions about Texas’ place in the reform movement and highlight the need for scholars and others to problematize both old and new forms of justice involvement and related sanctions which may not be adequately considered in the contemporary discourse.

With over 7 million misdemeanor cases and over $1 billion in legal financial obligations collected at the misdemeanor level in just one year, it is hard to conceptualize Texas as a model reform state. Yet, in the past few years Texas has exhibited decreases in the state prison population and has been hailed as a model for decreasing incarceration nationwide (Chettiar et al. 2015; Dunklee and Larsen 2015). We argue that both the policy and scholarly discourse has conveniently overlooked the much larger and often invisible population that interacts with the criminal legal system through misdemeanors. Moreover, traffic citations are criminalized in the state of Texas and thus carry with them criminal sanctions. In the event of non-payment, even a traffic ticket can thus trigger the risk of on-going and heightened surveillance by criminal legal authorities in Texas and other states.

Low-level misdemeanor offenses such as traffic violations are ubiquitous. Estimates suggest that in any given year one in ten U.S. drivers will receive a citation for a traffic violation (Davis, Whyde, and Langton 2018). As Howard Becker observed decades ago, “we think of the person who commits a traffic violation or gets a little too drunk at a party as being, after all, not very different from the rest of us and treat his infractions tolerantly” (1963). Consistent with a growing body of research on disproportionate policing (Baumgartner et al. 2018; Edelman 2019; Fagan et al. 2016; O’Neil and Prescott 2019), our research shows that people living in marginalized communities are also more likely to be burdened by legal debt for even these types of low-level infractions. These observations along with evidence that the collection of legal fines and fees operate under similar logics as other forms of punishment heightens the importance of recognizing their place in the contemporary field of punishment and, relatedly, their implications for inequality.

Legal fines and fees for misdemeanors are a profligate form of American punishment. They widen the net of criminal justice contact and their effects are borne most heavily by those who are already poor and disadvantaged (Beckett and Harris 2011; Friedman and Pattillo 2019; Harris et al. 2010). Low-level misdemeanors can be both ubiquitous and still unequal. Legal fines and fees contribute to a two-tiered system of justice where those who can pay can elude further sanctions or scrutiny. Those who cannot pay may be subject to a wide range of additional sanctions, surveillance, and consequences. Even minor citations can have long-term consequences leading to repeated court appearances (Kohler-Hausmann 2018), continued surveillance (Brayne 2014) and more extensive entanglements with the criminal legal system (Rios 2011). Legal fines and fees, even for misdemeanor citations, have become a defining feature of a contemporary punishment regime where racial injustice is fueled by economic inequality.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Matthew Snidal and Carmen Gutierrez for excellent research assistance and members of the Crime, Law, and Deviance workshop at the University of Texas at Austin for helpful comments and suggestions. This research was supported by grant P2CHD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

APPENDIX

Table A1.

Data Sources and Variable Construction

| Variable | Years | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Financial Obligations (LFO) | 1995-2016 | Texas Office of Court Administration (2018) |

| LFO per Capita ($) | ||

| LFO Cases per Capita | ||

| Percent Republican Vote | 1996-2016 | Texas Secretary of the State (2019) |

| Total Population Estimates | 1995-2016 | U.S. Census Bureau (2019) |

| Population Demographics | 1990, 2000, 2010 | U.S. Census Bureau (2019) |

| Percent Black | U.S. Census Bureau (2019) | |

| Percent Latinx | U.S. Census Bureau (2019) | |

| Black Percent Change (1yr) | U.S. Census Bureau (2019) | |

| Latinx Percent Change (1yr) | U.S. Census Bureau (2019) | |

| Mean Income ($) | Gann et al. (2017) | |

| Poverty Rate | Gann et al. (2017) | |

| Unemployment Rate | Gann et al. (2017) | |

| Police per 10,000 | 2004-2016 | Texas Department of Public Safety (2016) |

| Crime per 1,000 | 2004-2016 | Texas Department of Public Safety (2016) |

| Incarceration per 100,000 | 2010-2016 | Texas Department of Criminal Justice (2016) |

| Debt per Capita ($) | 2003-2016 | Texas Bond Review Board (2016) |

Table A2.

Alternative Sanctions, 2016

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied by Community Service in Part | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 2.7% |

| Satisfied by Community Service in Full | 1.3% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 18.7% |

| Jail Credit | 8.8% | 8.6% | 0.0% | 47.2% |

| Indigency Waiver | 0.5% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 20.5% |

| Percent of Collections Waived | 0.5% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 19.9% |

Source: Office of Court Administration (2016)

Table A3.

Regression on Log of Percent of Cases Satisfied by Fulltime Community Service, 2016

| OLS | Robust | M-estimator | MM-estimator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Republican | −0.019 (0.008)* | −0.019 (0.009)* | −0.018 (.010) | −0.018 (.010) |

| Percent Black | 0.007 (0.016) | 0.007 (0.015) | 0.008 (0.015) | 0.008 (0.018) |

| Percent Latinx | −0.001 (.006) | −0.001 (0.007) | 0.000 (0.008) | 0.005 (0.009) |

| Black Pop Growth | −0.008 (0.020) | −0.008 (0.028) | −0.003 (0.039) | 0.004 (0.084) |

| Latinx Pop Growth | 0.235 (0.075)** | 0.235 (0.088)** | 0.243 (0.107)* | 0.264 (0.196) |

| Debt per Capita | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Mean Income | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Poverty Rate | 0.035 (0.014)* | 0.035 (0.018) | 0.045 (0.023)* | 0.059 (0.028)* |

| Unemployment Rate | −0.003 (0.021) | −0.003 (0.023) | 0.001 (0.026) | 0.006 (0.031) |

| Police | −0.025 (0.005)** | −0.025 (0.005)** | −0.025 (0.005)** | −0.023 (0.005)** |

| Crime Rate | 0.029 (0.008)** | 0.029 (0.009)** | 0.026 (0.010)** | 0.019 (0.011) |

| Incarceration Rate | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Population | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Constant | −4.674 (1.196)** | −4.674 (1.211)** | −4.96 (1.334)** | −5.366 (1.478)** |

| R2 | 0.27 | 0.27 | ||

| N | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 |

p<0.05

p<0.01; Two-tailed tests.

Table A4.

Regression on Log of Percent of Cases Satisfied by Jail Credit

| OLS | Robust | M-estimator | MM-estimator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Republican | −0.004 (0.010) | −0.004 (0.012) | 0.000 (0.012) | 0.009 (0.008) |

| Percent Black | 0.059 (0.018)** | 0.059 (0.015)** | 0.054 (0.014)** | 0.053 (0.010)** |

| Percent Latinx | 0.005 (0.007) | 0.005 (0.008) | 0.008 (0.007) | 0.015 (0.006)* |

| Black Pop Growth | −0.010 (0.023) | −0.010 (0.022) | 0.002 (0.019) | 0.002 (0.016) |

| Latinx Pop Growth | 0.253 (0.086)** | 0.253 (0.098)** | 0.186 (0.094)* | 0.097 (0.064) |

| Debt per Capita | 0.000 (0.000)** | 0.000 (0.000)** | 0.000 (0.000)** | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Mean Income | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Poverty Rate | 0.000 (0.016) | 0.000 (0.020) | 0.016 (0.021) | 0.008 (0.016) |

| Unemployment Rate | 0.024 (0.024) | 0.024 (0.027) | 0.013 (0.027) | 0.026 (0.019) |

| Police | −0.037 (0.006)** | −0.037 (0.006)** | −0.037 (0.007)** | −0.084 (0.016)** |

| Crime Rate | 0.014 (0.009) | 0.014 (0.009) | 0.006 (0.010) | 0.002 (0.008) |

| Incarceration Rate | 0.001 (0.000)** | 0.001 (0.000)** | 0.001 (0.000)* | 0.001 (0.000) |

| Population | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Constant | −4.498 (1.363)** | −4.498 (1.641)** | −4.559 (1.655)** | −4.732 (1.208)** |

| R2 | 0.38 | 0.38 | ||

| N | 254 | 254 | 254 | 254 |

p<0.05

p<0.01; Two-tailed tests.

Footnotes

During the height of America’s penal expansion, sentence enhancements were routinely added to criminal codes allowing judges to levy penalties in excess of normal guidelines. See, for example, Kessler and Levitt 1999.

We estimate intercensal county population estimates. Supplemental results, available on request, use Texas state demographer projections.

Lloyd Bentsen was the last Democrat elected to the U.S. Senate from Texas. He was last elected in 1988, two years before the 1990 election of Ann Richards, the last Democrat elected governor of Texas. Texas has favored Republican presidential candidates consistently since 1980.

See Footnote 3.

The effects of debt are mixed and are sensitive to modeling specification. In reduced form models (Table 2), debt has a positive and significant relationship with collections. When the model is fully specified, however, the effect of debt is negative and significant, suggesting it is correlated with other county level measures. When we transform the dependent variable to address the effects of outlying and potentially influential cases (Table 3) the effect of debt is positive and significant in reduced form models. However, in the full model, there is no significant relationship between debt and the log of collections. When we examine the log of collections over time and with alternate estimators, effects are again mixed and make it difficult for us to draw strong conclusions about the relationship between debt and collections at the county level. Taken together, there is evidence to suggest that on the face of it, counties with proportionately large debt are also more likely to collect more in legal fines and fees, per capita. However, these results do not withstand further scrutiny and suggest that collections may be coincidentally higher in those counties but that, net other county level measures, there is not a consistent relationship.

REFERENCES

- Baicker Katherine, and Jacobson Mireille. 2007. “Finders Keepers: Forfeiture Laws, Policing Incentives, and Local Budgets.” Journal of Public Economics 91(11):2113–2136. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner Frank R., Epp Derek A., and Shoub Kelsey. 2018. Suspect Citizens: What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us About Policing and Race. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Howard S. 1963. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett Katherine. 1997. Making Crime Pay: Law and Order in Contemporary American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett Katherine, and Harris Alexes. 2011. “On Cash and Conviction: Monetary Sanctions as Misguided Policy.” Criminology & Public Policy 10(3):509–37. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett Katherine, and Murakawa Naomi. 2012. “Mapping the Shadow Carceral State: Toward an Institutionally Capacious Approach to Punishment.” Theoretical Criminology 16(2):221–44. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett Katherine, and Western Bruce. 2001. “Governing Social Marginality: Welfare, Incarceration, and the Transformation of State Policy.” Punishment & Society 3(1):43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein Alfred. 1993. “Racial Disproportionality of U.S. Prison Populations Revisited.” University of Colorado Law Review 64:743–60. [Google Scholar]

- Brayne Sarah. 2014. “Surveillance and System Avoidance: Criminal Justice Contact and Institutional Attachment.” American Sociological Review 79(3):367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Brett Sharon. Forthcoming. “Reforming Monetary Sanctions, Reducing Police Violence.” UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Michael C. 2011. “Politics, Prisons, and Law Enforcement: An Examination of the Emergence of ‘Law and Order’ Politics in Texas.” Law & Society Review 45(3):631–65. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Michael C., and Schoenfeld Heather. 2013. “The Transformation of America’s Penal Order: A Historicized Political Sociology of Punishment.” American Journal of Sociology 118(5):1375–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Caplow Theodore, and Simon Jonathan. 1999. “Understanding Prison Policy and Population Trends.” Crime and Justice 26:63–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chambliss William J. 1994. “Policing the Ghetto Underclass: The Politics of Law and Law Enforcement.” Social Problems 41(2):177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Chettiar Inimai, Waldman Michael, Fortier Nicole, and Finkelman Abigail. 2015. “Solutions: American Leaders Speak Out on Criminal Justice.” New York: Brennan Center for Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Chiricos Theodore G., and Delone Miriam A.. 1992. “Labor Surplus and Punishment: A Review and Assessment of Theory and Evidence.” Social Problems 39(4):421–446. [Google Scholar]

- Curry Philip A., and Klumpp Tilman. 2007. “Statistical Discrimination in the Criminal Justice System: The Case for Fines Instead of Jail.” Available at SSRN. https://Ssrn.Com/Abstract=983598. [Google Scholar]

- Davey Joseph Dillon. 1998. The Politics of Prison Expansion: Winning Elections by Waging War on Crime. Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Elizabeth, Whyde Anthony, and Langton Lynn. 2018. “Contacts Between Police and the Public, 2015.” Bureau of Justice Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Death Penalty Information Center. 2019. Execution Database. Washington, DC: Death Penalty Information Center. [Google Scholar]