Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic highlighted the importance of vaccine innovation in public health. Hundreds of vaccines built on numerous technology platforms have been rapidly developed against SARS-CoV-2 since 2020. Like all vaccine platforms, an important bottleneck to viral-vectored vaccine development is manufacturing. Here, we describe a scalable manufacturing protocol for replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 Spike-pseudotyped vesicular stomatitis virus (S-VSV)–vectored vaccines using Vero cells grown on microcarriers in a stirred-tank bioreactor. Using Cytodex 1 microcarriers over 6 days of fed-batch culture, Vero cells grew to a density of 3.95 ± 0.42 ×106 cells/mL in 1-L stirred-tank bioreactors. Ancestral strain S-VSV reached a peak titer of 2.05 ± 0.58 ×108 plaque-forming units (PFUs)/mL at 3 days postinfection. When compared to growth in plate-based cultures, this was a 29-fold increase in virus production, meaning a 1-L bioreactor produces the same amount of virus as 1,284 plates of 15 cm. In addition, the omicron BA.1 S-VSV reached a peak titer of 5.58 ± 0.35 × 106 PFU/mL. Quality control testing showed plate- and bioreactor-produced S-VSV had similar particle-to-PFU ratios and elicited comparable levels of neutralizing antibodies in immunized hamsters. This method should enhance preclinical and clinical development of pseudotyped VSV-vectored vaccines in future pandemics.

Keywords: Vero, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, omicron, VSV, microcarrier, Cytodex 1, spinner flask, vaccine

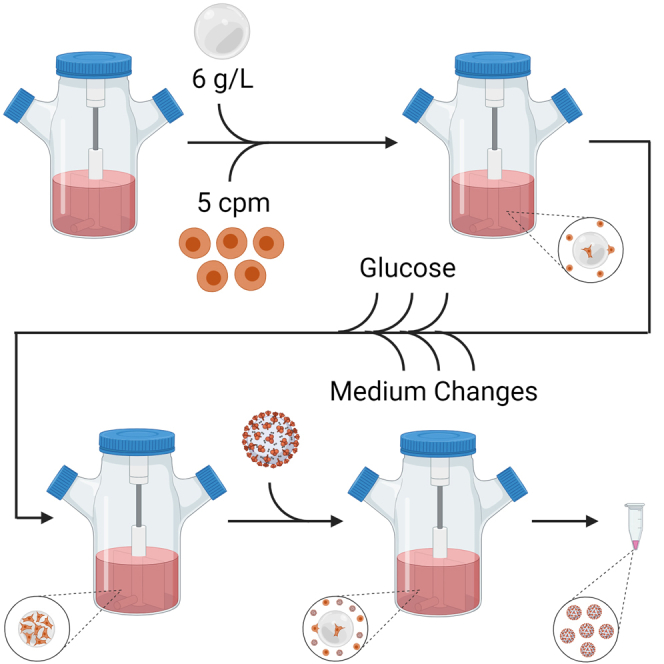

Graphical abstract

Todesco and colleagues describe a scalable manufacturing protocol for high-titer replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 Spike-pseudotyped vesicular stomatitis virus (S-VSV)–vectored vaccines using Vero cells grown on microcarriers in a stirred-tank bioreactor. This method should enhance preclinical and clinical development of pseudotyped VSV-vectored vaccines in future pandemics.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the novel β-coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), spurred global vaccine development at an unmatched pace. Hundreds of COVID-19 vaccines have been created since 2020, with nearly 200 having entered human clinical trials (as of March 2023).1 Over 13 billion COVID-19 vaccinations have now been administered around the world, delivered using numerous technology platforms, including mRNA (Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna), nonreplicating viral vectors (AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson), and inactivated viruses (Sinopharm and Sinovac).2 Although mRNA vaccines have emerged as the gold standard, they are not without limitations.3,4 mRNA vaccines are relatively slow to generate protective immunity, which begins to wane within months postvaccination and is not sterilizing. This results in a need for repeated booster vaccination to maintain protective immunity against SARS-CoV-2.5

Vaccines built on replicating viral vectors may not suffer from these limitations, especially when delivered intranasally, where they elicit both a systemic and local mucosal immune response that can reduce replication and shedding in the upper respiratory tract.6,7,8,9 Indeed, numerous replicating viral-vectored vaccines have been developed for COVID-19,9 including several on the recombinant vesicular stomatitis cirus (rVSV) platform.10 VSV is a nonsegmented single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus within the family Rhabdoviridae. The rVSV platform was successfully used as an Ebola virus disease vaccine, where it was engineered to express the Zaire Ebola virus glycoprotein (rVSV-ZEBOV).11,12,13 A similar approach has also been used against other filoviruses,14 as well as Zika virus15,16 and SARS-CoV-1.17,18 More recently, reports from several groups19,20,21 have described the development of rVSV-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, including Brilife (IIBR-100) which entered Phase II clinical trials and was shown to be safe and effective in humans.22,23

Similar to other vaccine platforms, however, manufacturing is a major bottleneck in the development of rVSV-vectored vaccines. rVSV-based vaccines are typically manufactured using Vero cells, the most widely used continuous adherent cell line for viral-vectored vaccines,24,25 including rVSV-ZEBOV,11,12,13 poliovirus,26,27,28 rabies,29,30,31 SARS-CoV-1,32,33 and VSV.34 Vero cells have been routinely grown on microcarriers since the 1960s in bioreactors and now reach volumes up to 6,000 L.25 This method frequently achieves volumetric viral titers 100-fold higher than growing cells as a monolayer in Nunc Cell Factory or roller bottle systems, while still allowing easy separation of cells from a supernatant containing released viruses.35 In contrast to fixed-bed systems such as the Esco CelCradle or Pall iCELLis, the equipment required for stirred-tank bioreactors are less complex, easier to scale, and lower cost.

Despite being used for decades, inconsistent culture vessel geometry, medium choice, and other culture conditions have resulted in highly variable Vero cell growth in microcarrier bioreactor cultures.36 This hampers robust, high-titer manufacturing of viral-vectored vaccines. To address this, we sought to establish optimized culture parameters for bench-scale Vero cell growth and subsequent production of Spike (S)-pseudotyped rVSV in a microcarrier-based spinner flask system. We focused on optimizing microcarrier type, inoculum density, microcarrier density, run length, medium supplementation, MOI, and scale-up, with rVSV pseudotyped with both the ancestral and BA.1 variant S sequences of SARS-CoV-2. In addition to helping establish a method that could be translated from the lab to the clinic, the optimized process we describe here could accelerate preclinical vaccine production using Vero cells for future pandemic crises.

Results

Microcarrier selection and optimization of Vero cell growth conditions

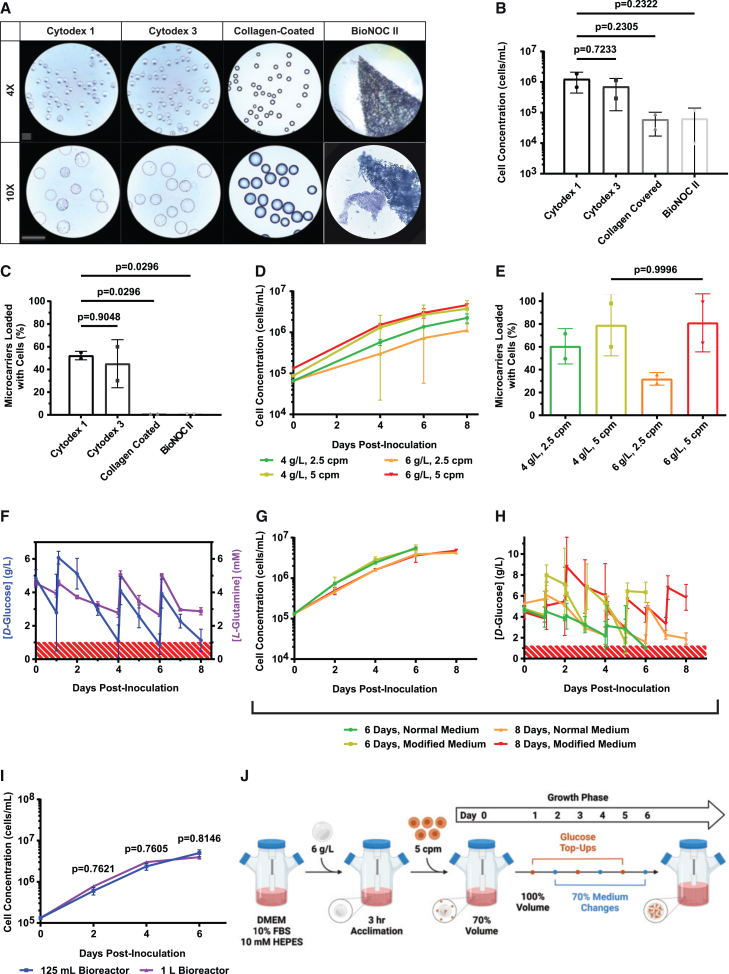

Our first objective was to compare several commercially available microcarriers for Vero cell attachment and growth in a stirred-tank bioreactor. Cytodex 1 (dextran), Cytodex 3 (collagen-covered dextran), collagen-coated (collagen-covered polystyrene), and BioNOC II (fibrous polyester) microcarriers were selected for comparison. Stirred tank 125-mL spinner flask bioreactors were established with 2,200 cm2 of microcarrier surface area (equivalent to 4 g/L of Cytodex 1), inoculated with 2,500 cells/cm2 (equivalent to 2.5 cells per Cytodex 1 microcarrier (cpm)) and incubated for 4 days at 60 rpm at 37°C with 5% CO2 in air. After 4 days, there was little or no visible cell attachment on collagen-coated or BioNOC II carriers (Figure 1A). In contrast, Cytodex 1 and Cytodex 3 carriers had observable Vero cell attachment on their surfaces. Crystal violet nuclei staining showed that cultures grown on Cytodex 1 and Cytodex 3 harbored a similar number of Vero cells (1.26 ± 0.83 ×106 and 7.13 ± 5.98 ×105 cells, respectively), whereas cultures containing collagen-coated and BioNOC II harbored approximately 16-fold fewer cells (5.98 ± 4.27 ×104 and 6.37 ± 7.65 ×104 cells, respectively) (Figure 1B). Furthermore, there were significantly more Vero cells growing directly on Cytodex 1 microcarriers versus Collagen-Coated (p = 0.0296) or BioNOC II (p = 0.0296), but no difference in the number of Vero cells growing on Cytodex 1 versus Cytodex 3 (p = 0.9048) (Figure 1C). Although Cytodex 1 and Cytodex 3 both supported Vero cell growth, we selected Cytodex 1 for further investigation because it is less expensive and does not contain animal-derived collagen.

Figure 1.

Microcarrier selection and optimization of Vero cell growth conditions

(A) Bright-field images of crystal violet–stained Vero cells on indicated microcarriers in 125-mL Celstir bioreactors. Microcarriers were inoculated with 2,500 cells/cm2 and incubated for 4 days before imaging. Scale bar, 360 μm. (B) Cell concentration for the bioreactor runs in (A) after 4 days of culture. (C) Microcarrier loading percentage for the bioreactor runs in (A) after 4 days of culture. (D) Cell concentration from Cytodex 1 microcarriers with densities of 4 or 6 g/L and inoculated with 2.5 or 5 Vero cpm. Cultures were monitored for 8 days with 70% medium replacements on days 4, 6, and 8. (E) Microcarrier loading percentage for bioreactor runs in (D) after 8 days of culture. (F) d-glucose and l-glutamine medium concentrations for Vero cell cultures containing 5 cpm grown for 8 days on 6 g/L Cytodex 1 with 70% medium replacements on days 4, 6, and 8. Red area denotes d-glucose concentrations below 1 g/L and l-glutamine concentrations below 1 mM. (G) Cell concentration from Vero cell cultures containing 5 cpm grown on 6 g/L Cytodex 1 with 70% medium replacements on days 2, 4, and 6 or days 4, 6, and 8 for 6- or 8-day runs, respectively. Bioreactor runs with modified medium had 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, and 2.25 g/L d-glucose added on days 1, 3, and 5 or days 2, 5, and 7 for 6- or 8-day runs, respectively. (H) d-Glucose medium concentrations for the bioreactor runs in (G). Red area denotes d-glucose concentrations below 1 g/L. (I) Density of cells in 125-mL or 1-L Celstir bioreactors containing 5 cpm grown for 6 days on 6 g/L Cytodex 1 with modified medium undergoing 70% manual medium replacements on days 2, 4, and 6 with 2.25 g/L d-glucose top-ups on days 1, 3, and 5. (J) Schematic of optimized 6-day Vero cell growth protocol in 125-mL and 1-L Celstir bioreactors. Mean ± SD is shown. Data points represent the mean of 2 replicates unless stated otherwise. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) was used in (B), (C), (E), and (G). One-way ANOVA with Sidak’s HSD was used in (I). For (F), n = 6 for d-glucose and n = 2 for l-glutamine measurements. For (I), n = 2 for 125-mL bioreactors and n = 4 for 1-L bioreactors.

Our next objective was to optimize Vero cell growth on Cytodex 1. To achieve this, we first tested a range of microcarrier densities (4 or 6 g/L) and Vero cell seeding densities (2.5 or 5 cpm) for 8 days of culture, with 70% of the medium replaced on days 4, 6, and 8. These experiments showed that altering cpm significantly affected Vero cell growth kinetics, whereas altering Cytodex 1 density had minimal effect (Figure 1D). Specifically, on day 8 both 4 g/L 5 cpm and 6 g/L 5 cpm conditions supported higher cell densities than the 2.5-cpm conditions (p = 0.0458 and 0.0069, respectively). Indeed, both 4 g/L 5 cpm and 6 g/L 5 cpm had over 80% microcarrier occupancy on day 8 (Figure 1E). With no significant difference between 4 and 6 g/L, we selected 6 g/L of Cytodex 1 and 5 cpm for further optimization given the greater available surface area for cell growth.

We then sought to optimize nutrient content within the cell culture medium. A total of 6 g/L of Cytodex 1 and 5 cpm were cultured with 70% medium changes on days 4, 6, and 8. Medium samples were collected before and after each change, which showed d-glucose concentrations frequently falling below 1 g/L (Figure 1F, blue line), a limit past which both cell growth and viability are known to decline.29,37,38 l-Glutamine was also quantified to estimate amino acid depletion in the culture medium (Figure 1F, purple line), but levels stayed above 2 mM.13,26 In an attempt to improve the medium, we tested whether 10 mM HEPES buffer and d-glucose top-ups (to maintain levels above 1 g/L) enable better Vero cell growth. In these experiments, 125 mL bioreactor cultures were established using 6 g/L of Cytodex 1 and 5 cpm, with 70% medium changes on days 2, 4, and 6, or days 4, 6, and 8, for 6- and 8-day runs, respectively. Within each run-length group, bioreactor cultures were fed normal medium or medium supplemented with 10 mM HEPES and d-glucose. Interestingly, the final cell counts for 6-day normal medium runs were similar to those of 8-day normal medium runs (p = 0.1172), which suggests that more-frequent medium changes allow the run length to be shortened by 2 days without sacrificing cell yield (Figure 1G). Although normal and modified medium 6-day runs showed no significant difference in cell growth, we nevertheless selected modified medium for further studies to avoid d-glucose depletion (Figure 1H).

Finally, we sought to scale up the optimized 6-day Vero cell growth protocol with modified medium to 1-L bioreactors. Here, bioreactor runs had 6 g/L of Cytodex 1 with 5 cpm, 70% medium changes on days 2, 4, and 6, and d-glucose top-ups on days 1, 3, and 5. A total of 10 mM HEPES was also added to all of the cell culture medium. In these experiments, Vero cell growth was nearly identical in either 125-mL or 1 L-bioreactors (p = 0.7586) (Figure 1I). This scalable protocol for establishing a high-yield Vero cell culture in stirred-tank bioreactors is summarized in Figure 1J.

Production of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 and VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP in stirred-tank bioreactors

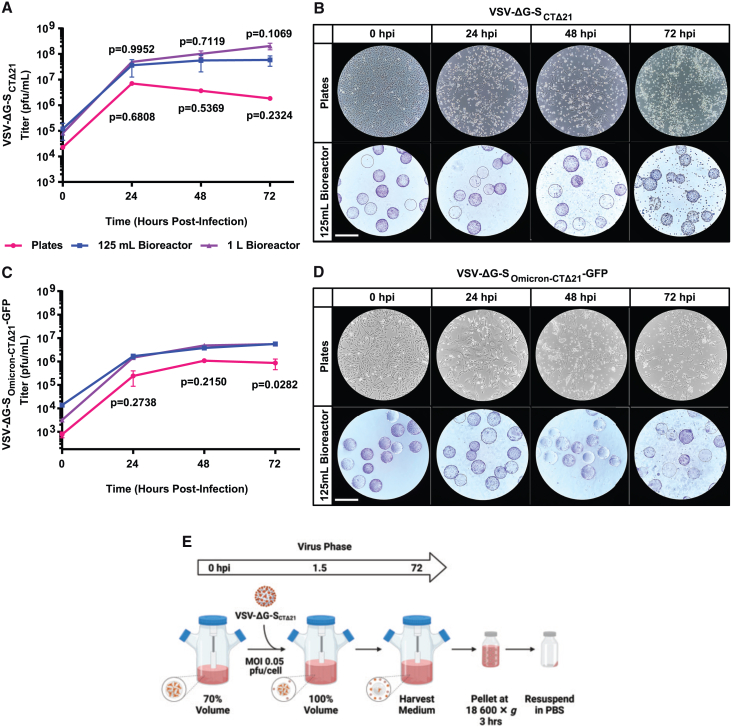

Using the optimized Vero cell culture protocol described above, we evaluated the production of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21, a replicating viral-vectored rVSV vaccine pseudotyped with the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain S protein, against a standard plate-based method for virus production. First, we sought to optimize MOI for both plates (Figure S1) and 125-mL bioreactors (Figure S2). Virus titers generated by plates or bioreactors infected at various MOIs showed no significant difference after 72 h of infection. Second, we infected either plates or 125-mL bioreactors with an MOI of 0.05 plaque-forming unit (PFU)/cell and medium was harvested and titered at the indicated time points. Plate-based production resulted in a peak mean titer of 7.02 ± 0.05 × 106 PFU/mL at 24 h postinfection (hpi) that decreased to 1.84 ± 0.30 × 106 PFU/mL at 72 hpi, whereas 125-mL bioreactor-based production resulted in a mean titer of 3.63 ± 2.38 × 107 PFU/mL at 24 hpi that further increased to 5.88 ± 2.59 × 107 PFU/mL by 72 hpi (Figure 2A). Cytopathic effect (CPE) was also seen in all growth conditions (Figure 2B). We also sought to examine virus production when scaled up to 1 L. VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 growth was similar in 125-mL and 1-L bioreactors; however, the 1-L bioreactors had a higher mean cell-specific virus yield of 45.7 ± 12.2 PFU/cell compared to 8.57 ± 2.60 PFU/cell in 125-mL bioreactors (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Optimization of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 and VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP production in 125-mL and 1-L bioreactors

(A) Growth curves with VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 in plate- and bioreactor-based virus production runs. We infected 145-cm2 tissue culture plates and 125-mL and 1-L Celstir bioreactors at an MOI of 0.05 PFU/cell. Cultures were harvested at the indicated times and titered on Vero cells. (B) Bright-field images of Vero cells in a 145-cm2 plate or crystal violet–stained Vero cells grown on Cytodex 1 microcarriers in 125-mL Celstir bioreactors. Cultures were infected with an MOI of 0.05 PFU/cell with VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21. Scale bar, 360 μm. (C) Growth curves with VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP in plate- and bioreactor-based virus production runs. We infected 145-cm2 tissue culture plates and 125-mL and 1-L bioreactors with an MOI of 0.002 PFU/cell and harvested at the indicated times and titered on Vero cells. (D) Bright-field images of Vero cells in a 145-cm2 plate or crystal violet–stained Vero cells grown on Cytodex 1 microcarriers in 125-mL bioreactors. Cultures were infected with an MOI of 0.002 PFU/cell with VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP. Scale bar, 360 μm. (E) Schematic of optimized 72-h VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 virus production protocol in 125-mL and 1-L Celstir bioreactors. Mean ± SD is shown. Two-way ANOVA using Sidak’s HSD was used in (A) and (B). For (A), n = 2 for plates, n = 4 for 125-mL and 1-L bioreactors. p values from pairwise comparisons between plates and 125-mL bioreactors are shown below the line graph; comparisons between 125-mL and 1-L bioreactors are shown above the line graph. For (B), n = 2 for plates, n = 2 for 125-mL bioreactor, and n = 1 for 1-L bioreactor. p values are generated only from comparisons between plates and 125-mL bioreactors.

Next, we compared the production of an rVSV pseudotyped with the BA.1 omicron S protein, VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP, again in plates and bioreactors. Using the same optimized culturing conditions (Figure 1J), VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP reached a mean titer of 3.75 ± 0.35 × 106 PFU/mL at 48 h that further increased to 5.58 ± 0.35 × 106 PFU/mL at 72 h in the 125-mL bioreactors (Figure 2C). Meanwhile, plates had a peak titer of 1.09 ± 0.02 × 106 PFU/mL at 48 h that decreased to 8.59 ± 4.12 × 105 PFU/mL at 72 h The 125-mL bioreactors had a significantly higher titer than plates at 72 h (p = 0.0282). Scaling up to the 1-L bioreactor produced similar titers to the 125-mL bioreactor runs at each time point (Figure 2C). Despite this, the PFU/cell yield for this omicron variant was highest in plates at 3.70 ± 0.07 PFU/cell compared to 1.12 ± 0.06 and 1.82 PFU/cell in 125-mL and 1-L bioreactors, respectively (Table S1). In addition, VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP caused more syncytia-like morphology both on plates and microcarriers with less CPE (Figure 2D). The virus infection protocol and the downstream processing steps for bioreactors are summarized in Figure 2E.

Characterization of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 produced in stirred-tank bioreactors

Finally, we wanted to compare the physical and functional properties of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 produced by either the plate- or bioreactor-based method. Defective interfering (DI) particles are noninfectious viral genome–containing particles generated during viral replication. Many viruses, including VSV,39 make DIs that have been shown to trigger the innate immune response.40 To determine the ratio of DI particles to infectious particles, we used a tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) instrument, which allows for single particle–based quantification and size profiling. This revealed no significant difference in the ratio of infectious to noninfectious viral particles generated in plates versus bioreactors (4.75 ± 1.12 ×102 and 3.89 ± 0.66 ×102 particles:PFU, respectively, p = 0.5085) (Figure S3).

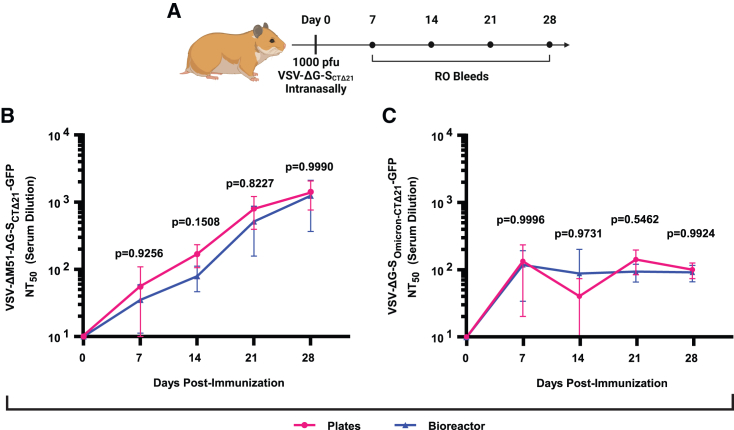

Next, we sought to determine the immunogenicity of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 produced by either the plate- or bioreactor-based method. We used Golden Syrian hamsters for these studies, which are an established model system for recapitulating respiratory disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 and generating neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) in response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.41,42 Golden Syrian hamsters were immunized with 1 × 103 PFU VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 delivered intranasally, using plate- or bioreactor-produced vaccine (Figure 3A). Blood was collected over 28 days for measuring serum neutralizing titer 50 (NT50), determined by a pseudovirus plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) using both ancestral and omicron SARS-CoV-2 S-pseudotyped rVSVs. Vaccination with either plate- or bioreactor-produced VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 generated a sharp initial increase in serum nAb titers against both the ancestral and omicron variant S-pseudotyped rVSVs (Figures 3B and 3C). nAb titers against the ancestral S-pseudotyped rVSV steadily increased up to 28 days postvaccination, with no significant difference between plate- or bioreactor-produced virus (Figure S4). In contrast, nAb titers against the omicron SARS-CoV-2 S-pseudotyped rVSV plateaued after the initial increase. However, there was still no significant difference between plate or bioreactor produced virus.

Figure 3.

Characterization of virus produced using bioreactors

(A) Animal experiment schematic of retro-orbital (RO) bleed schedule. (B) Mean NT50 values using VSV-ΔM51-ΔG-SCTΔ21-GFP in vitro from animals vaccinated intranasally with 1 × 103 PFU of plate- or 1-L bioreactor-produced pellet stocks of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21. (C) Mean NT50 values using VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP in vitro from animals vaccinated intranasally with 1 × 103 PFU of plate- or 1-L bioreactor-produced pellet stocks of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21. Mean ± SD is shown. Two-way ANOVA using Sidak’s HSD was used in (B) and (C). For (B) and (C), n = 4.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 produced using stirred-tank bioreactors were physically and functionally like those produced using conventional plate-based manufacturing. Stirred-tank bioreactors grew cells to a higher density, had greater cell-specific virus yield, and produced higher-titer ancestral strain S-pseudotyped rVSV for a reduced cost compared to plate-based manufacturing (Tables S1 and S2).

Discussion

Scalable virus manufacturing is essential to the production of both live and inactivated viral-vectored vaccines. Replicating viral vectors not only provide promise as vaccines but also play a critical role in basic research (e.g., understanding pathogenic virus entry mechanisms19) and diagnostic assays (e.g., PRNTs9). The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in an unprecedented development of vaccines, but a major bottleneck for viral-vectored vaccine production is scalability. Here, we show a multifactor optimization of Vero cell growth in stirred-tank bioreactors and the scalable production of a replication-competent pseudotyped rVSV expressing the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral (VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21) and omicron S (VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP) that could also be adapted for other viral-vectored vaccines.

Although several cell lines have been used as virus manufacturing platforms, Vero cells are the most widely accepted continuous adherent cell line for manufacturing human viral vaccines.24,43 Originating from the African vervet monkey, these cells have been used for decades to produce polio and rabies vaccines, with an absence of interferon production and oncogenic properties, making them a safe and attractive platform for human use.25 In this study, we were interested in exploring microcarriers in stirred-tank bioreactors as a cost-effective solution for lab-based scalable vaccine production. In general, monolayer cultures using roller bottles or multilayer cultures such as the Corning HYPERStack cell culture vessels have been used for virus manufacturing. However, at larger scales, these systems can become labor intensive and difficult to monitor. More recently, fixed- or packed-bed bioreactors systems such as the CelCradle and iCELLis have been developed. These systems have been shown to reach Vero cell densities of 4.0–6.7 ×106 cells/mL.44,45,46 However, they are not well suited for lab-scale virus production, having high upfront costs and difficult cell visualization.

Stirred-tank bioreactors are widely used in cell culture–based viral vaccine production and provide an efficient and cost-effective platform. We therefore compared several common microcarriers, Cytodex 1, Cytodex 3, collagen-coated, and BioNOC II, and found that Cytodex 1 and 3 supported cell growth similarly in initial 4-day cultures. Our batch-mode 125-mL bioreactors had a mean cell density of 4.62 ± 0.42 ×106 cells/mL after first optimizing microcarrier and inoculum concentrations. Similarly, Trabelsi et al. achieved cell densities of 3.6 ± 0.2 ×106 cells/mL on 6 g/L of Cytodex 1 after optimizing microcarrier concentration,47 with several additional studies reporting efficient Vero cell growth on Cytodex 1 microcarriers.47,48,49 Meanwhile, our BioNOC II carriers only achieved cell densities of 6.37 ± 7.65 ×104 cells/mL, which is lower than other reports using fixed-bed systems.44 This may be due to our use of a stirred-tank bioreactor instead of a tide-motion bioreactor. Supplementation with HEPES buffer and d-glucose top-ups achieved mean final cell densities of 5.28 ± 1.36 ×106 cells/mL in 125-mL stirred-tank bioreactors in 6 days as compared to 4.78 ± 0.08 ×106 cells/mL in the original 6-day fed-batch protocol. The manufacturing process was successfully scaled up to 1-L bioreactors while maintaining cell densities at 3.95 ± 0.42 ×106 cells/mL. Overall, our optimization of the fed-batch process was able to achieve similar or higher cell densities as those reported in the literature for serum-containing cultures.

A recent report from Ton et al. showed successful scaling of Vero cells on Cytodex 1 or similar Cytodex 1-Gamma microcarriers from 2 to 2,000 L using commercial serum-free medium in a comparable fed-batch system.50 The full description of their Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-scale bioreactor protocols provides a potential pathway for larger-scale production beyond our 1-L system using the parameters optimized here. However, the microcarrier and inoculum densities they used were shown to be less effective in our system, limiting their cell densities and virus titers of an rVSV-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to a maximum of 2.7 ×106 cells/mL and 2.9 × 107 PFU/mL, respectively.

Although we attempted to optimize the MOI used for our plate- and bioreactor-based virus production, we found no effect of increasing MOI from 0.01 to 0.10 PFU/cell on VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 growth or peak titer. Although this was unexpected, Rosen et al. also found no significant difference in peak medium titer when inoculating with MOIs of 0.001–1.0 PFU/cell of VSV-ΔG-S in a serum-free Ambr15 system.51 In addition, our 1-L bioreactor peak mean titer of 2.05 ± 0.58 × 108 PFU/mL for rVSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 is similar to their titer for a comparable vaccine (rVSV-ΔG-S) of 1.5–3.5 × 108 PFU/mL in a 14-mL microbioreactor at 37°C. With VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP, our mean medium titer of 5.58 ± 0.35 × 106 PFU/mL in 125-mL bioreactors is, to our knowledge, the first described for an omicron S-pseudotyped rVSV in a bioreactor system. The lower virus titers for omicron S-pseudotyped rVSV suggest that further optimization is needed to improve the yield of this virus.

These successful small-scale culture protocols can allow larger batches of vaccine doses to be prepared for preclinical work during future pandemic responses. A 1-L bioreactor was able to produce higher total cell numbers, greater PFU/cell, and reduced cost/PFU, while occupying a smaller area inside an incubator and using a similar run length compared to plate-based production of the ancestral strain S-pseudotyped rVSV. In addition, plastic waste is reduced significantly compared to single-use tissue culture dishes. Using peak titers of ancestral strain S-pseudotyped rVSV, it would take 272 plates to culture the same number of cells as a single 1-L bioreactor, and 1,284 plates to produce the same amount of PFUs (Table S1). Being more efficient and scalable than plate-based production, this well-optimized process could also be used to produce virus that is suitable for vaccine challenge studies, diagnostic assays, and fundamental vaccine and virology research.

The limitations of our study include the small size of each experimental group. This substantially affected our statistical power, especially when the effect size was small or the biological variability was high. As such, our interpretations are sometimes based on nonsignificant data trends. We also only tested virus production using wild-type Vero (CCL-81) cells. Further titer increases may be achievable with Vero cells ectopically expressing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and/or TMPRSS2.52 We also did not test every commercially available microcarrier or optimize every manufacturing parameter. Improvements could be made by converting our system to microporous microcarriers such as CultiSpher-G to obtain higher cell yields. The porous features of the CultiSpher-G microcarriers have been shown to yield 3-fold higher cell densities than on Cytodex 1.53 Others have shown improvements in virus production, including reducing the temperature to 32.5°C –34°C.13,50,54,55 We may also produce higher cell densities and virus yields using perfusion as demonstrated for other vectors.56 Finally, transitioning to serum-free medium as others have done with rVSV-ZEBOV and rVSV-SARS-CoV-2 would help align with GMP when expanding beyond a 1-L scale.13,50,55

In summary, our study provides a method for producing high titer and functional SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain and omicron variant BA.1 S-pseudotyped rVSV using a laboratory-scale stirred-tank bioreactor. Assuming the middle human vaccine dose used in the IIBR-100 vaccine clinical trial of 1 × 106 PFU,23 approximately 200,000 doses could be manufactured from a 1-L culture, and there is likely still room for additional optimization and improvement. The method is scalable, amenable to GMP, and likely transferrable to the production of other viruses and vaccines in Vero cells.

Materials and methods

Animals and study design

Animal experiments and procedures were approved by the University of Calgary Health Sciences Animal Care Committee (AC20-0053). Animal health and wellness was monitored using the Health Sciences Animal Care Committee Rodent Wellness Assessment form and standard operating procedure. Male Golden Syrian hamsters 6–8 weeks old (Charles River, strain code no. 049) were vaccinated by intranasal inoculation. Anesthetized animals were inoculated with 1 ×103 PFU of VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 in 25 μL delivered dropwise into the nostrils of the hamster under anesthesia. Animals were randomly allocated to groups, and group sizes are indicated within each figure legend. Blood was collected by retro-orbital bleeding in accordance with University of Calgary animal care protocols, and serum was harvested and stored using a standard procedure. At the end of the study, hamsters were humanely euthanized via cardiac puncture while under isoflurane anesthesia.

Cell lines

Vero (CCL-81) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The Lenti-X 293T (catalog no. 632180) cell line was obtained from Takara Bio. Vero and Lenti-X 293T cell lines were maintained in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. 11965118) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. 12484028) and were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 at high humidity. All of the lines were routinely tested for, and found free of, mycoplasma, either by Hoechst 33342 staining (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and fluorescence imaging or using the LookOut Mycoplasma PCR detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Spike pseudotyped VSV

pVSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 and VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21 plasmids were constructed by replacing the native VSV (Indiana strain) glycoprotein sequence with the Wuhan-Hu-1 (GenBank: MN908947.3) or BA.1 isolates (GenBank: OL672836.1) of SARS-CoV-2 S sequence that was codon optimized by GenScript USA for human expression from VSV and contained a 21-amino acid deletion in the cytoplasmic tail. GFP-expressing viruses were also constructed by introducing the sequence downstream of S. To rescue infectious virions, Lenti-X 293T cells constitutively expressing human ACE2 were infected with vaccinia virus encoding the T7 RNA polymerase. Cells were then transfected with plasmids encoding VSV N, P, L, and G, and pVSV plasmid described above. Rescued virus was collected 72 h posttransfection, clarified (15 min at 3,000 × g), and filtered twice through a 0.22-μm filter. Virus was triple plaque purified on Vero cells and clones were verified by next-generation sequencing to contain no erroneous mutations with greater than 10% read frequency. Viral stocks were prepared by infecting Vero cells at an MOI of 0.02 PFU/cell. At 72 hpi, medium was collected and clarified (15 min at 3,000 × g). Virus was then pelleted with the J-Lite JLA-10.500 Fixed-Angle Rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 18,600 × g and 4°C and then resuspended in PBS, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Plate-based virus preparation

Viral stocks were prepared by infecting Vero cells at an MOI of 0.05 or 0.002 PFU/cell for VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 and VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP, respectively. At 72 hpi, medium was collected and clarified (15 min at 3,000 × g). Virus was then pelleted with the J-Lite JLA-10.500 Fixed-Angle Rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 18,600 × g and 4°C, then resuspended in PBS, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Bioreactor setup

Initial setup

The 125-mL or 1-L Celstir spinner flasks (catalog nos. 356876 and 356884) were assembled and siliconized using Sigmacote (Millipore Sigma, catalog no. SL2-100ML) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Cytodex 1, 2,200 cm2/L (Cytiva, catalog no. 17044801), Cytodex 3 (Cytiva, catalog no. 17048502), collagen-coated (Corning, catalog no. 3786), and BioNOC II (Chemglass Life Sciences, catalog no. CLS-1344-01) were rehydrated and sterilized in siliconized Erlenmeyer flasks according to their respective manufacturer’s instructions. After this microcarrier comparison, 6 g/L of Cytodex 1 was consistently used. Microcarriers were rinsed with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. 15140122) before being transferred to a sterilized bioreactor using a siliconized 5-mL glass pipette. The working volume was increased to 70% using the medium above and allowed to equilibrate at 37°C in 5% CO2 and a 60 rpm stirring rate for a minimum of 3 h. Unless stated otherwise, bioreactors were inoculated with 5 cells per microcarrier. After 24 h, the working volume was increased to 100%.

Medium changes

The 6-day bioreactor run schedule had medium changes on days 2, 4, and 6; the 8-day schedule had medium changes on days 4, 6, and 8. Medium changes began with the removal of a 3.5-mL sample while the impeller was spinning at 60 rpm to obtain an evenly distributed microcarrier sample. An additional 0.5-mL sample was collected from the clear overlying medium once the impeller stopped and microcarriers had settled to the bottom. A total of 70% of the bioreactor medium was then removed via tilting and carefully pipetting the culture medium out without aspirating any microcarriers. Fresh medium was then added to restore the working volume to 100% and the bioreactor was returned to incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2, high humidity, and a 60-rpm stirring rate.

Infection

The 6-day bioreactor run schedule had infection on day 6; the 8-day schedule had infection on day 8. After 70% of the culture medium was removed during the final medium change, fresh culture medium was added to restore the working volume to 70%, and the bioreactor was returned to the incubator while cell counts were performed. Using the bioreactor’s total cell count, the cells were infected at an MOI of 0.01, 0.03, 0.05, or 0.10 PFU/cell using VSV-ΔG-SCTΔ21 from a plate viral stock added directly to the bioreactor medium. The infection was allowed to progress at 70% working volume for 90 min incubating at 37°C, 5% CO2, high humidity, and a 60-rpm stirring rate before culture medium was added to increase the working volume to 100%.

Harvesting

Bioreactors incubated for 72 h after infection before the impeller was stopped, microcarriers settled, and all of the infected culture medium was collected via careful pipetting at an angle. The infected medium was clarified, concentrated, and stored as described above.

Medium modifications

A concentrated d-glucose stock was prepared by dissolving 13.81 g of d-glucose in 50 mL DMEM (which already contains 4.5 g/L d-glucose) and filter sterilizing the solution through a 0.22-μm filter to produce a 307.5-g/L stock. The top-up volume was 1 mL for the 125-mL bioreactor runs and 8 mL for the 1-L bioreactor runs, which was accounted for during subsequent medium changes to ensure a constant working volume of 125 mL or 1 L. Bioreactor runs with modified medium had 10 mM HEPES (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. 15630106) always added and d-glucose top-ups added periodically on days 1, 3, and 5 for 6-day bioreactor run schedules and days 2, 5, and 7 for 8-day schedules.

Crystal violet cell counts, imaging, and microcarrier loading estimates

Cells were counted in triplicate as described by Rourou et al.29 Briefly, 3 mL of the 3.5-mL Vero cell culture sample was divided into three 1-mL aliquots, washed 3 times with 700 μL PBS, and then treated in 700 μL of 0.1 M citric acid (Millipore Sigma, catalog no. 251275) containing 0.1% crystal violet (Millipore Sigma, catalog no. C6158) and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Millipore Sigma, catalog no. X100), and incubated at least for 1 h at 37°C. The released nuclei were counted using a hemacytometer. For imaging, the remaining 500 μL of the 3.5-mL sample was added to a 6-well polystyrene plate containing 750 μL PBS and 20 μL 0.5% crystal violet in >99.9% methanol (Millipore Sigma, catalog no. MX0486) for 10 min. A total of 750 μL of a 30% Percoll (Cytiva, catalog no. 17089102) in PBS mounting solution was added to the stained sample, gently mixed, and then microcarriers were immediately imaged using an Echo Revolve inverted microscope and counted.

d-Glucose quantification

Medium samples were collected and stored at −80°C until use. Samples were diluted 2- or 5-fold in ultrapure distilled water (Thermo Fisher, catalog no. 10977015) and analyzed in triplicate using a d-glucose assay kit in a 96-well plate format (Megazyme, catalog no. K-GLUC) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, d-glucose was converted to the pink compound quinoneimine by reacting with glucose oxidase followed by peroxidase. d-Glucose concentrations were quantified based on each processed sample’s absorbance at 510 nm using a SpectraMax i3 plate reader (Molecular Devices), with each absorbance value averaged from duplicate readings and the path length corrected to 1 cm.

l-Glutamine quantification

Medium samples were collected and stored at −80°C until use. Samples were diluted 25-fold in ultrapure distilled water and analyzed in duplicate using an l-glutamine assay kit in a 96-well plate format (Abcam, catalog no. ab197011) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, l-glutamine was converted to l-glutamate and ammonium by reacting with glutaminase, followed by the ammonium by-products reacting with a proprietary developer enzyme to produce an l-glutamine-equivalent amount of an unknown yellow compound. l-Glutamine concentrations were quantified based on each processed sample’s absorbance at 450 nm using a SpectraMax i3 plate reader (Molecular Devices), with each absorbance value averaged from duplicate readings and the path length corrected to 1 cm.

Titering

Medium from infected cells was collected at the indicated times. This medium was diluted in serum free DMEM and plated in duplicate on Vero cells in 6-well plates. Infected Vero cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS containing 1% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) (Millipore Sigma, catalog no. C5013) for 3 days, and then fixed and stained with crystal violet. Where possible, plaque counts were determined from wells containing 30–150 plaques.

Particle counting

Virus particles were quantified using TRPS with the Izon qNano Particle Counter (IZON Science) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, calibration beads and virus samples were diluted in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 detergent (Millipore Sigma, catalog no. P1379). Samples were run on a 150-nm pore (IZON Science, catalog no. NP150) until 1,000 events were captured. IZON Control Suite 3.2 software was used to process the data and determine the particle concentration and size.

PRNT

For the pseudovirus PRNT assays, Vero cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 2 ×104 cells/well. Hamster serum was heat inactivated for 30 min at 56°C, then 2-fold serially diluted in PBS. Diluted serum was mixed 1:1 with 100 PFU of replication-competent VSV pseudotyped with the S gene of ancestral SARS-CoV-2 containing a 21-amino acid C-terminal truncation and expressing GFP (VSV-ΔM51-ΔG-SCTΔ21-GFP) or VSV-ΔG-SOmicron-CTΔ21-GFP (as described above) to a final serum dilution of 1:32 to 1:1,024. Serum-virus mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then added to Vero cells and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS containing 1% CMC was then added and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. GFP+ plaques were imaged at 4× magnification using an InCell 6000 (Cytiva) and counted automatically using the MIPAR image analysis suite. The dilution achieving 50% neutralization (NT50) was estimated by nonlinear regression curve fit using GraphPad Prism 9.1.1 (GraphPad Software). All of the samples were run in duplicate by a blinded technician.

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.1.1. Statistical significance was given when p values were <0.05. Statistical tests, number of animals or samples, average values, and statistical comparison groups are indicated in the figure legends. All of the values are reported as mean ± SD.

Data and code availability

All of the data discussed in the manuscript are available in the main text or the supplemental information.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant 448323 (to D.J.M.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, K.G.P. and D.J.M. Methodology, H.M.T., C.G., E.L.R., B.S.B., A.P., M.S.K., K.G.P., and D.J.M. Investigation, H.M.T., C.G., C.M.J., and K.G.P. Writing – original draft, H.M.T. and K.G.P. Writing – review & editing, H.M.T., E.L.R., M.S.K., K.G.P., and D.J.M. Supervision, K.G.P. and D.J.M. Funding acquisition, D.J.M.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2024.101189.

Contributor Information

Kyle G. Potts, Email: kyle.potts@ucalgary.ca.

Douglas J. Mahoney, Email: djmahone@ucalgary.ca.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.WHO . 2022. World Health Organization. DRAFT Landscape of COVID-19 Candidate Vaccines, November, 2022.https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tregoning J.S., Flight K.E., Higham S.L., Wang Z., Pierce B.F. Progress of the COVID-19 vaccine effort: viruses, vaccines and variants versus efficacy, effectiveness and escape. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021;21:626–636. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00592-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collier A.R.Y., Yu J., McMahan K., Liu J., Chandrashekar A., Maron J.S., Atyeo C., Martinez D.R., Ansel J.L., Aguayo R., et al. Differential Kinetics of Immune Responses Elicited by Covid-19 Vaccines. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:2010–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2115596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menni C., May A., Polidori L., Louca P., Wolf J., Capdevila J., Hu C., Ourselin S., Steves C.J., Valdes A.M., et al. COVID-19 vaccine waning and effectiveness and side-effects of boosters: a prospective community study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022;22:1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chenchula S., Karunakaran P., Sharma S., Chavan M. Current evidence on efficacy of COVID-19 booster dose vaccination against the Omicron variant: A systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:2969–2976. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King R.G., Silva-Sanchez A., Peel J.N., Botta D., Dickson A.M., Pinto A.K., Meza-Perez S., Allie S.R., Schultz M.D., Liu M., et al. Single-Dose Intranasal Administration of AdCOVID Elicits Systemic and Mucosal Immunity against SARS-CoV-2 and Fully Protects Mice from Lethal Challenge. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:881. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhama K., Dhawan M., Tiwari R., Emran T.B., Mitra S., Rabaan A.A., Alhumaid S., Alawi Z.A., Al Mutair A. COVID-19 intranasal vaccines: current progress, advantages, prospects, and challenges. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18 doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2045853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bricker T.L., Darling T.L., Hassan A.O., Harastani H.H., Soung A., Jiang X., Dai Y.-N., Zhao H., Adams L.J., Holtzman M.J., et al. A single intranasal or intramuscular immunization with chimpanzee adenovirus-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine protects against pneumonia in hamsters. Cell Rep. 2021;36:109400. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavda V.P., Bezbaruah R., Athalye M., Parikh P.K., Chhipa A.S., Patel S., Apostolopoulos V. Replicating Viral Vector-Based Vaccines for COVID-19: Potential Avenue in Vaccination Arena. Viruses. 2022;14:759. doi: 10.3390/v14040759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawson N.D., Stillman E.A., Whitt M.A., Rose J.K. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses from DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:4477–4481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldmann H., Feldmann F., Marzi A. Ebola: Lessons on Vaccine Development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;72:423–446. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suder E., Furuyama W., Feldmann H., Marzi A., de Wit E. The vesicular stomatitis virus-based Ebola virus vaccine: From concept to clinical trials. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14:2107–2113. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1473698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiesslich S., Vila-Chã Losa J.P., Gélinas J.F., Kamen A.A. Serum-free production of rVSV-ZEBOV in Vero cells: Microcarrier bioreactor versus scale-X™ hydro fixed-bed. J. Biotechnol. 2020;310:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geisbert T.W., Daddario-DiCaprio K.M., Williams K.J.N., Geisbert J.B., Leung A., Feldmann F., Hensley L.E., Feldmann H., Jones S.M. Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Vector Mediates Postexposure Protection against Sudan Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever in Nonhuman Primates. J. Virol. 2008;82:5664–5668. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00456-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emanuel J., Callison J., Dowd K.A., Pierson T.C., Feldmann H., Marzi A. A VSV-based Zika virus vaccine protects mice from lethal challenge. Sci. Rep. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29401-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li A., Xue M., Attia Z., Yu J., Lu M., Shan C., Liang X., Gao T.Z., Shi P.-Y., Peeples M.E., et al. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus and DNA Vaccines Expressing Zika Virus Nonstructural Protein 1 Induce Substantial but Not Sterilizing Protection against Zika Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00048-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapadia S.U., Rose J.K., Lamirande E., Vogel L., Subbarao K., Roberts A. Long-term protection from SARS coronavirus infection conferred by a single immunization with an attenuated VSV-based vaccine. Virology. 2005;340:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapadia S.U., Simon I.D., Rose J.K. SARS vaccine based on a replication-defective recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus is more potent than one based on a replication-competent vector. Virology. 2008;376:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieterle M.E., Haslwanter D., Bortz R.H., Wirchnianski A.S., Lasso G., Vergnolle O., Abbasi S.A., Fels J.M., Laudermilch E., Florez C., et al. A Replication-Competent Vesicular Stomatitis Virus for Studies of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Mediated Cell Entry and Its Inhibition. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:486–496.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yahalom-Ronen Y., Tamir H., Melamed S., Politi B., Shifman O., Achdout H., Vitner E.B., Israeli O., Milrot E., Stein D., et al. A single dose of recombinant VSV-ΔG-spike vaccine provides protection against SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:6402–6413. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malherbe D.C., Kurup D., Wirblich C., Ronk A.J., Mire C., Kuzmina N., Shaik N., Periasamy S., Hyde M.A., Williams J.M., et al. A single dose of replication-competent VSV-vectored vaccine expressing SARS-CoV-2 S1 protects against virus replication in a hamster model of severe COVID-19. Npj Vaccines. 2021;6:91. doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00352-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yahalom-Ronen Y., Erez N., Fisher M., Tamir H., Politi B., Achdout H., Melamed S., Glinert I., Weiss S., Cohen-Gihon I., et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Variants by rVSV-ΔG-Spike-Elicited Human Sera. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:291. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levin Y., Balakirski N.M., Caraco Y., Ben-Ami E., Atsmon J., Marcus H. Ethics and execution of developing a 2nd wave COVID vaccine – Our interim phase I/II VSV-SARS-CoV2 vaccine experience. Vaccine. 2021;39:2821–2823. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knezevic I., Stacey G., Petricciani J., Sheets R. Evaluation of cell substrates for the production of biologicals: Revision of WHO recommendations. Report of the WHO Study Group on Cell Substrates for the Production of Biologicals, 162-169 April 2009, Bethesda, USA. Biologicals. 2010;38:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett P.N., Mundt W., Kistner O., Howard M.K. Vero cell platform in vaccine production: Moving towards cell culture-based viral vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2009;8:607–618. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomassen Y.E., van der Welle J.E., van Eikenhorst G., van der Pol L.A., Bakker W.A. Transfer of an adherent Vero cell culture method between two different rocking motion type bioreactors with respect to cell growth and metabolic rates. Process Biochem. 2012;47:288–296. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomassen Y.E., Rubingh O., Wijffels R.H., van der Pol L.A., Bakker W.A.M. Improved poliovirus D-antigen yields by application of different Vero cell cultivation methods. Vaccine. 2014;32:2782–2788. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merten O.W., Wu R., Couvé E., Crainic R. Evaluation of the serum-free medium MDSS2 for the production of poliovirus on Vero cells in bioreactors. Cytotechnology. 1997;25:35–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1007999313566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rourou S., van der Ark A., van der Velden T., Kallel H. A microcarrier cell culture process for propagating rabies virus in Vero cells grown in a stirred bioreactor under fully animal component free conditions. Vaccine. 2007;25:3879–3889. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frazatti-Gallina N.M., Mourão-Fuches R.M., Paoli R.L., Silva M.L.N., Miyaki C., Valentini E.J.G., Raw I., Higashi H.G. Vero-cell rabies vaccine produced using serum-free medium. Vaccine. 2004;23:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu P., Huang Y., Zhang Y., Tang Q., Liang G. Production and evaluation of a chromatographically purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV) in China using microcarrier technology. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2012;8:1230–1235. doi: 10.4161/hv.20985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qu D., Zheng B., Yao X., Guan Y., Yuan Z.H., Zhong N.S., Lu L.W., Xie J.P., Wen Y.M. Intranasal immunization with inactivated SARS-CoV (SARS-associated coronavirus) induced local and serum antibodies in mice. Vaccine. 2005;23:924–931. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin E., Shi H., Tang L., Wang C., Chang G., Ding Z., Zhao K., Wang J., Chen Z., Yu M., et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy in monkeys of purified inactivated Vero-cell SARS vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24:1028–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiesslich S., Kim G.N., Shen C.F., Kang C.Y., Kamen A.A. Bioreactor production of rVSV-based vectors in Vero cell suspension cultures. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021;118:2649–2659. doi: 10.1002/bit.27785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Healthcare G. 2005. Microcarrier Cell Culture: Principles and Methods; pp. 1–172. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallo-Ramírez L.E., Nikolay A., Genzel Y., Reichl U. Bioreactor concepts for cell culture-based viral vaccine production. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2015;14:1181–1195. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.1067144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kluge S., Rourou S., Vester D., Majoul S., Benndorf D., Genzel Y., Rapp E., Kallel H., Reichl U. Proteome analysis of virus-host cell interaction: rabies virus replication in Vero cells in two different media. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97:5493–5506. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4939-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J., Guertin P., Jia G., Lv Z., Yang H., Ju D. Large-scale microcarrier culture of HEK293T cells and Vero cells in single-use bioreactors. Amb. Express. 2019;9:70. doi: 10.1186/s13568-019-0794-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pattnaik A.K., Ball L.A., LeGrone A.W., Wertz G.W. Infectious defective interfering particles of VSV from transcripts of a cDNA clone. Cell. 1992;69:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90619-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linder A., Bothe V., Linder N., Schwarzlmueller P., Dahlström F., Bartenhagen C., Dugas M., Pandey D., Thorn-Seshold J., Boehmer D.F.R., et al. Defective Interfering Genomes and the Full-Length Viral Genome Trigger RIG-I After Infection With Vesicular Stomatitis Virus in a Replication Dependent Manner. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.595390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sia S.F., Yan L.M., Chin A.W.H., Fung K., Choy K.T., Wong A.Y.L., Kaewpreedee P., Perera R.A.P.M., Poon L.L.M., Nicholls J.M., et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in golden hamsters. Nature. 2020;583:834–838. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2342-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imai M., Iwatsuki-Horimoto K., Hatta M., Loeber S., Halfmann P.J., Nakajima N., Watanabe T., Ujie M., Takahashi K., Ito M., et al. Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS-CoV-2 infection and countermeasure development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:16587–16595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009799117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Genzel Y. Designing cell lines for viral vaccine production: Where do we stand? Biotechnol. J. 2015;10:728–740. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Offersgaard A., Duarte Hernandez C.R., Pihl A.F., Costa R., Venkatesan N.P., Lin X., Van Pham L., Feng S., Fahnøe U., Scheel T.K.H., et al. SARS-CoV-2 production in a scalable high cell density bioreactor. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:706. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen K., Li C., Wang Y., Shen Z., Guo Y., Li X., Zhang Y. Optimization of vero cells grown on a polymer fiber carrier in a disposable bioreactor for inactivated coxsackievirus a16 vaccine development. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:613. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajendran R., Lingala R., Vuppu S.K., Bandi B.O., Manickam E., Macherla S.R., Dubois S., Havelange N., Maithal K. Assessment of packed bed bioreactor systems in the production of viral vaccines. Amb. Express. 2014;4:25–27. doi: 10.1186/s13568-014-0025-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trabelsi K., Rourou S., Loukil H., Majoul S., Kallel H. Optimization of virus yield as a strategy to improve rabies vaccine production by Vero cells in a bioreactor. J. Biotechnol. 2006;121:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu S.C., Liu C.C., Lian W.C. Optimization of microcarrier cell culture process for the inactivated enterovirus type 71 vaccine development. Vaccine. 2004;22:3858–3864. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nor Y.A., Sulong N.H., Mel M., Salleh H.M., Sopyan I. The growth study of Vero cells in different type of microcarrier. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2010;01:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ton C., Stabile V., Carey E., Maraikar A., Whitmer T., Marrone S., Afanador N.L., Zabrodin I., Manomohan G., Whiteman M., Hofmann C. Development and scale-up of rVSV-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine process using single use bioreactor. Biotechnol. Rep. 2023;37 doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2023.e00782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosen O., Jayson A., Goldvaser M., Dor E., Monash A., Levin L., Cherry L., Lupu E., Natan N., Girshengorn M., Epstein E. Optimization of VSV-$∖Delta$G-spike production process with the Ambr15 system for a SARS-COV-2 vaccine. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022;119:1839–1848. doi: 10.1002/bit.28088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Case J.B., Rothlauf P.W., Chen R.E., Liu Z., Zhao H., Kim A.S., Bloyet L.-M., Zeng Q., Tahan S., Droit L., et al. Neutralizing Antibody and Soluble ACE2 Inhibition of a Replication-Competent VSV-SARS-CoV-2 and a Clinical Isolate of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:475–485.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ng Y.C., Berry J.M., Butler M. Optimization of physical parameters for cell attachment and growth on macroporous microcarriers. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996;50:627–635. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960620)50:6<627::AID-BIT3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuk I.H., Lin G.B., Ju H., Sifi I., Lam Y., Cortez A., Liebertz D., Berry J.M., Schwartz R.M. A serum-free Vero production platform for a chimeric virus vaccine candidate. Cytotechnology. 2006;51:183–192. doi: 10.1007/s10616-006-9030-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gélinas J.F., Azizi H., Kiesslich S., Lanthier S., Perdersen J., Chahal P.S., Ansorge S., Kobinger G., Gilbert R., Kamen A.A. Production of rVSV-ZEBOV in serum-free suspension culture of HEK 293SF cells. Vaccine. 2019;37:6624–6632. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ansorge S., Lanthier S., Transfiguracion J., Durocher Y., Henry O., Kamen A. Development of a scalable process for high-yield lentiviral vector production by transient transfection of HEK293 suspension cultures. J. Gene Med. 2009;11:868–876. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All of the data discussed in the manuscript are available in the main text or the supplemental information.