Abstract

Background

Armenia is considered particularly vulnerable to life-threatening vector-borne diseases (VBDs) including malaria, West Nile virus disease and leishmaniasis. However, information relevant for the control of the vectors of these diseases, such as their insecticide resistance profile, is scarce. The present study was conducted to provide the first evidence on insecticide resistance mechanisms circulating in major mosquito and sand fly populations in Armenia.

Methods

Sampling sites were targeted based mainly on previous historical records of VBD occurrences in humans and vertebrate hosts. Initially, molecular species identification on the collected vector samples was performed. Subsequently, molecular diagnostic assays [polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Sanger sequencing, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), quantitative PCR (qPCR)] were performed to profile for major insecticide resistance mechanisms, i.e. target site insensitivity in voltage-gated sodium channel (vgsc) associated with pyrethroid resistance, acetylcholinesterase (ace-1) target site mutations linked to organophosphate (OP) and carbamate (CRB) resistance, chitin synthase (chs-1) target site mutations associated with diflubenzuron (DFB) resistance and gene amplification of carboxylesterases (CCEs) associated with resistance to the OP temephos.

Results

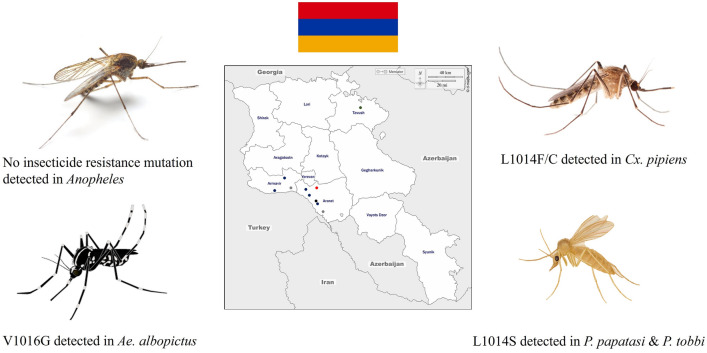

Anopheles mosquitoes were principally represented by Anopheles sacharovi, a well-known malaria vector in Armenia, which showed no signs of resistance mechanisms. Contrarily, the knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations V1016G and L1014F/C in the vgsc gene were detected in the arboviral mosquito vectors Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens, respectively. The kdr mutation L1014S was also detected in the sand fly, vectors of leishmaniasis, Phlebotomus papatasi and P. tobbi, whereas no mutations were found in the remaining collected sand fly species, P. sergenti, P. perfiliewi and P. caucasicus.

Conclusions

This is the first study to report on molecular mechanisms of insecticide resistance circulating in major mosquito and sand fly disease vectors in Armenia and highlights the need for the establishment of systematic resistance monitoring practices for the implementation of evidence-based control applications.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13071-024-06139-2.

Keywords: Malaria, Arboviruses, Leishmaniasis, Mosquitoes, Sand flies, Molecular insecticide resistance

Background

The geographical and climatic conditions of Armenia, a landlocked country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia, are favourable for arthropod vectors. Ninety-five percent (95.0%) of Armenia’s territory is considered susceptible to especially dangerous vector-borne diseases (VBDs) [1, 2].

Historically, a number of VBDs have been prevalent in Armenia, such as malaria [3], arboviral diseases [4–6] and leishmaniasis [7, 8]. Although a malaria elimination process was completed in 2005 in Armenia, the re-emergence of autochthonous malaria remains a constant threat [3]. This is also true for arboviral diseases; a previously conducted large entomological survey identified 125 distinct strains of 10 arboviruses, including major public health threats, such as West Nile virus (WNV) [2, 4, 5]. Leishmaniasis is another significant public health problem in Armenia, where both visceral (VL) and cutaneous (CL) forms have been recorded; from 1999 to 2021, 202 indigenous VL cases were registered, with 7 of those being fatal [1, 7, 8].

Mosquitoes of the genera Anopheles, Aedes and Culex are some of the most important vectors of infectious diseases in Armenia, relating to public health crises such as malaria, WNV and dengue. The vectors are spread over the territory of Armenia for most of the year (from April to November). Indeed, a comprehensive study performed in 2016 identified a total of 29 different species of mosquitoes. It identified 6 anophelines (including major malaria vectors Anopheles sacharovi and An. maculipennis s.s.), 10 Aedes (including Aedes albopictus, which can transmit dengue, chikungunya and other arboviruses) and 8 Culex species [including Culex pipiens, the major vector of WNV [2]. Regarding Phlebotomus sand flies, entomological surveys have shown an increase in their populations [1], referring also to key vectors such as Phlebotomus papatasi and P. sergenti [9]. Such a wide variety of vectors can complicate local transmission of endemic communicable diseases by causing the re-emergence of previously eliminated VBDs and is an important factor in the introduction of newly detectable diseases [10].

The use of chemical insecticides remains a fundamental and highly effective intervention tool for reducing all these vector populations, thus controlling the spread of VBDs during outbreaks [11]. In Armenia, in particular, the pyrethroids cypermethrin and cyfluthrin are used to control vectors in leishmaniasis and malaria foci, respectively [1]. However, the development of insecticide resistance in disease vectors threatens the effectiveness of vector control strategies [12–14]. In Armenia, resistance to pyrethroids has already been documented by Paronyan et al. in An. maculipennis s.l. and Cx. pipiens mosquitoes at the phenotypic level using WHO adult susceptibility bioassays [15].

Investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying insecticide resistance in wild vector populations through regular monitoring of resistance markers could lay the foundation for decision-making processes in vector control campaigns within the framework of evidence-based Insecticide Resistance Management (IRM) [15, 16].

Mechanisms of insecticide resistance include target-site resistance due to mutations in the target where the insecticide attacks and metabolic resistance due to overexpression of detoxification genes such as cytochrome P450s (CYPs), glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and carboxylesterases (CCEs) [13]. Regarding target site insensitivity, knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel (vgsc) gene have been previously associated with pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles (mutations: L1014F/C/S) [17], Culex (mutations: L1014F/C/S) [18] and Aedes (mutations: F1534C/L/S; V1016G/I; I1532T) [19] mosquito vectors as well as in Phlebotomus sand fly vectors (mutations L1014F/S) [14]. Resistance to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors organophosphates (OPs) and carbamate (CRB) is mediated by Ace-1 target-site mutations (G119S) and is found in Anopheles spp. and Cx. pipiens mosquitoes [20]. Chitin synthase (chs-1) mutations (I1043L/M/F), recorded so far in Cx. pipiens populations, have been strongly linked with resistance to the larvicide diflubenzuron (DFB) [21]. Concerning metabolic resistance, the overexpression of CCEs CCEae3a and CCEae6a is associated with temephos resistance in Ae. albopictus [22]. These mechanisms have already been reported mostly in mosquito (kdr, ace-1, chs-1 mutations, CCE upregulation) [15, 23–26] and sand fly [14] populations (kdr mutations) in Europe and neighbouring countries; however, relevant data are lacking for Armenia.

We performed the present study to provide a first snapshot of the molecular insecticide resistance mechanisms operating in major disease vectors in Armenia (Anopheles, Aedes, Culex mosquitoes and Phlebotomus sand flies) and possibly detect emerging resistance traits for better monitoring and management of resistance as early as possible.

Methods

Collection of mosquitoes and sand flies and sample handling

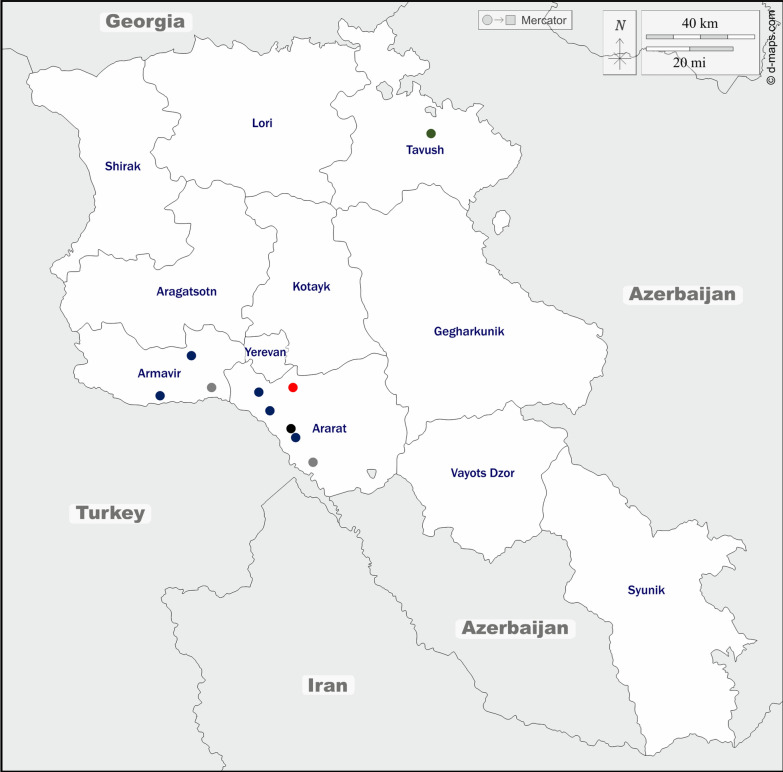

Samples were collected between September and October 2021 in the Ararat (including Yerevan), Armavir, Tavush and Yerevan provinces at the sites depicted in Fig. 1 and described in detail in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Fig. 1.

Mosquito (Anopheles: blue dots; Culex: black dot; both Anopheles and Culex: grey dots; Aedes: green dot) and sand fly (red dot) collection sites of the study. The base layers of the left panel’s maps were obtained from d-maps.com [59]

Ararat Province of Armenia is an area of 2090 km2, located at the southeast of the Ararat Valley. The annual amplitude of the average monthly air temperature in the Ararat Plain is the highest in the entire South Caucasus and reaches > 31 ℃. On average, about 220 mm of precipitation falls per year. The Ararat region comprises mostly marshy areas. The total area of the city of Yerevan is 223 km2. Yerevan is in the northeastern part of the Ararat valley, at an altitude of 900–1200 m above sea level. Yerevan, historically and currently, is one of the visceral leishmaniasis hotspots in Armenia. Naturally, about 70 animal species may act as reservoirs for Leishmania parasites, including humans [1].

The Armavir region of Armenia is in the southwest of the country, in the Ararat valley. Armavir has an area of 1242 km2. The province is entirely located at the heart of the Ararat plain, mainly consisting of agricultural lands, with an average height of 850 m above sea level. The climate of the Armavir region is strictly continental. Throughout the year, temperatures usually range from – 7 ℃ to 34 ℃. Annual precipitation is about 305 mm. The epidemic susceptibility in terms of VBDs in the region is like in Ararat. In 2021, one case of quartan malaria was recorded in the Echmiadzin region of Armavir in a patient with no travel history [1].

Tavush is a province of Armenia located in the northeast, bordered by Georgia from the north and Azerbaijan from the east. Tavush has an area of 2704 km2. More than 50.0% of Armenia's forest resources are in the Tavush region. The average annual temperature is about 10 ℃. Precipitation falls up to 563 mm per year. The main breeding sites for mosquitoes are swamps that form along river floodplains. Because of the frequent movement of riverbeds, backwaters are formed in the valley, as well as many small reservoirs, which are the main breeding grounds for mosquitoes. The close connection between mosquito breeding and river valleys is especially noticeable here [1].

Mosquitoes and sand flies were collected using Center for Disease Control (CDC)-type light traps supplied with 1.5 kg CO2. All insect collections were immediately stored in 70.0% ethanol and transferred to the laboratory where they were stored at − 20 ℃. Mosquitoes were morphologically identified to the genus level [27] and molecularly to the species level, and sand flies were molecularly identified at the species level. The sampling sites were selected based on a combination of factors prioritized per: (i) historical records of VBD occurrences in humans (e.g. Ararat, Armavir: high risk, former malaria hyperendemic zone, Yerevan: hotspot of visceral leishmaniasis) and vertebrate hosts, (ii) previous knowledge on sites with increased mosquito and sand fly populations and (iii) insecticide applications in leishmaniasis foci and intense use of pesticides for agricultural purposes (including the pyrethroids lambda-cyhalothrin and deltamethrin).

DNA extraction from mosquitoes and sand flies

Genomic DNA was extracted from a total of N = 104 individual insects (74 mosquitoes and 30 sand flies, Additional file 1: Table S1), using the DNAzol protocol according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), with the following modifications: 200 μl DNAzol reagent for homogenization, 100 μl absolute ethanol for DNA precipitation, air drying for 15 min on a heat-block set at 50 ℃ and solubilization of DNA in 15 μl DNase/RNase-free water. Samples were stored at − 20 ℃ until PCR analyses.

Molecular identification of mosquito and sand fly species

Mosquito species were molecularly identified as previously described [28, 29]. Briefly, members of Cx. pipiens were distinguished based on polymorphisms in the intron region of the acetylcholinesterase-2 gene (ace-2) and use of species-specific primers; samples that were identified as Cx. pipiens were further analysed to biotype (relying on polymorphisms in the 5ʹ flanking region of the microsatellite locus CQ11 [30]. Aedes albopictus identification was confirmed using the internal transcribed spacer two gene (ITS2) as described in [31]. Anopheles mosquitoes were molecularly differentiated by partial amplification of the ITS2 and mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I gene (COI) [32, 33]. Sand fly species discrimination was performed based on the COI genomic fragment, as previously described [29, 34].

Monitoring of molecular mechanisms of insecticide resistance

Using the outer primers and PCR conditions provided in [18], each Culex mosquito was genotyped for the presence of the kdr mutations L1014F/C/S in the vgsc gene. Anopheles specimens were also genotyped for the kdr mutations L1014F/C/S following the protocol described in [35]. Anopheles and Culex mosquitoes were tested for insensitive acetylcholinesterase (ace-1) mutations using the PCR-RFLP method as described in [20]. Monitoring of the kdr mutations V1016G (vgsc domain II) and I1532T and F1534C/L/S (vgsc domain III) in Ae. albopictus was performed using PCR amplification and sequencing of the relevant domain areas enclosing the mutation sites, as detailed in [36]. The presence of carboxylesterases 3 (CCEae3a) and 6 (CCEae6a) gene amplification events in Ae. albopictus were assayed as detailed in [24]. Aedes albopictus and Cx. pipiens specimens were also screened for the presence of the mutations I1043L/M/F in the chs-1 gene, as described in [24] and [21], respectively.

The presence of kdr mutations L1014F/S in individual sand fly samples was monitored by genotyping the vgsc domain IIS6, using the following de novo designed primers for PCR amplification: forward: 5ʹ-TTCCCAGACGGTGAAATGCC-3ʹ; reverse: 5ʹ-TCATTGTCTGCAGTTGGTGCT-3ʹ. The PCR reaction was performed using the KAPA Taq PCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, US) using 1.0 ul genomic DNA as a template with the following thermal protocol: 95 ℃ for 5 min, 35 cycles (95 ℃ for 30 s, 58 ℃ for 40 s, 72 ℃ for 30 s) and 72 ℃ for 5 min. The generated PCR fragments of approximately 250 bp were purified after visualization in agarose gel (1.5% w/v) using the Nucleospin PCR & Gel Clean-Up Kit (Macherey Nagel, Dueren, Germany) and then subjected to Sanger sequencing (GENEWIZ, Azenta Life Sciences, Germany) using the forward primer. Sequences were analysed using the BioEdit sequence alignment editor 7.2 (https://bioedit.software.informer.com/7.2/). We additionally developed an assay to determine the possible presence of the N1575Y super kdr (skdr) mutation, associated with enhanced pyrethroid resistance in mosquito vector species, based on the published sequences of Anopheles gambiae (XM_318122, NCBI) and Phlebotomus papatasi (PPAI003017-RA, VectorBase). Direct sequencing (Sanger) of the vgsc gene was applied to all samples carrying the conventional kdr mutations L1014F/S to detect any presence of the skdr mutation. PCR reactions (25 ul) were performed, containing 1 × PCR Buffer A (Kapa Biosystems), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.30 mM each dNTP, 0.3 μM of each primer (Fskdr: 5-CACGCTCAACCTGTTCATTGG-3ʹ and Rskdr: 5ʹ-AGGAAGTCCAGCGTCTTGC-3ʹ), 1.25U Kapa Taq DNA Polymerase (Kapa Biosystems) and 1.0 ul genomic DNA. PCR was performed using the following temperature cycling conditions: 5 min at 95 ℃, followed by 30 s at 95 ℃, 40 s at 56 ℃, 30 s at 72 ℃ for 35 cycles and 5 min at 72 ℃ for the final extension. PCR products (312 bp) were then separated by agarose gel (1.5% w/v) electrophoresis, cleaned up using the Nucleospin PCR & Gel Clean-Up Kit (Macherey Nagel, Dueren, Germany) and sequenced from both directions by GENEWIZ (Azenta Life Sciences, Germany).

Results

Mosquito and sand fly species identification

Most Anopheles mosquitoes of Ararat Province (93.8%) belonged to the An. sacharovi species, with a few individuals identified as An. claviger and An. hyrcanus. In Armavir Province, all Anopheles mosquitoes were identified as An. maculipennis s.s. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mosquito and sand fly species composition in the study areas

| Vector | Population | Species ID/biotype | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anopheles mosquitoes | Ararat (Jrarat, Hovtashen, Masis, Taperakan, Ararat) | An. sacharovi | 30 (93.8%) |

| An. claviger | 1 (3.1%) | ||

| An. hyrcanus | 1 (3.1%) | ||

| Armavir (Metsamor, Janfida) | An. maculipennis s.s | 3 (100.0%) | |

| Aedes mosquitoes | Tavush (Ijevan) | Ae. albopictus | 26 (100.0%) |

| Culex mosquitoes | Armavir (Jrarat) | Cx. pipiens biotype pipiens | 4 (100.0%) |

| Ararat (Shahumyan, Ararat) | Cx. pipiens biotype pipiens | 8 (88.9%) | |

| Cx. pipiens biotype molestus | 1 (11.1%) | ||

| Phlebotomus sand flies | Yerevan (Jrashen) | P. papatasi | 19 (65.5%) |

| P. tobbi | 5 (17.2%) | ||

| P. sergenti | 3 (10.3%) | ||

| P. perfiliewi | 1 (3.5%) | ||

| P. caucasicus | 1 (3.5%) |

Regarding Culex mosquitoes, the Armavir region sampling site consisted only of the Cx. pipiens biotype pipiens, whereas both Cx. pipiens biotype pipiens (88.9%) and Cx. pipiens biotype molestus (11.1%) were detected in Ararat.

All Aedes mosquitoes sampled in Tavush Province were Ae. albopictus species. Aedes albopictus was the only species of the Aedes genus mosquitoes sampled in the Tavush region (Table 1).

Concerning the sand fly species composition in Yerevan Province, P. papatasi was the dominant species (65.5%), followed by P. tobbi (17.2%) and P. sergenti (10.3%), whereas P. perfiliewi and P. caucasicus were detected at 3.5% each (Table 1). Representative electropherograms of the COI gene region for each of the sand fly species detected are presented in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Monitoring of insecticide resistance mechanisms in mosquito and sand fly vectors

Anopheles mosquitoes from all study sites were analysed for the presence of kdr mutations L1014F, L1014C, and L1014S, associated with pyrethroid resistance and of the G119S mutation associated with OPs and CRB resistance, but none of these mutations were detected.

Aedes albopictus mosquitoes were tested for a total of six kdr mutations (i.e. V1010G, V1010GI, I1532T, F1534C, F1534L and F1534S). The V1016G mutation was detected, albeit at a very low frequency (mutant allelic frequency = 1.9%; 1 heterozygote mosquito). The presence of CCEae3a and CCEae6a amplification, associated with OP (temephos) resistance, as well as the presence of chs-1 mutations (I1043L, I1043M, and I1043F), linked with diflubenzuron (DFB) resistance, were also investigated in the study’s Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, but neither of these two mechanisms was detected.

Culex pipiens mosquitoes were analysed for the presence of kdr mutations L1014F, L1014C and L1014S. Of those mutations, L1014F was detected with a mutant allelic frequency of 25.0% in the Armavir population and of 14.3% in the Ararat population, which additionally harboured the L1014C mutation at a frequency of 28.6%. None of the OP/CRB and DFB resistance mechanisms tested (G119S and I1043L/M/F mutations, respectively) were detected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Investigation of insecticide resistance mechanisms in the study’s Culex pipiens populations

| Population | Associated insecticides | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrethroids | OP/CRB | DFB | |||

| Resistant mutation allelic frequencies (hetero/homo), V of alleles | |||||

| L1014F | L1014C | L1014S | G119S | I1043L/M/F | |

| Armavir (Jrarat) | 25.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| (2/0) | (0/0) | (0/0) | (0/0) | (0/0) | |

| N = 8 | N = 8 | N = 8 | N = 8 | N = 8 | |

| Ararat (Ararat, Shahumyan) | 14.3% | 28.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| (0/2) | (1/2) | (0/0) | (0/0) | (0/0) | |

| N = 18 | N = 18 | N = 18 | N = 8 | N = 8 | |

OP/CRB: organophosphates/carbamates; DFB: diflubenzuron

The collected sand fly population from Yerevan (Jrashen) was analysed for the presence of kdr mutations L1014F and L1014S, and the latter was found in P. papatasi at a mutant allelic frequency of 42.1% and in P. tobbi at a frequency of 10.0% (Table 3 and electropherograms of wild-type and mutant samples in Additional file 1: Figure S2). Kdr-positive samples were additionally screened for the presence of the N1575Y skdr mutation, which, however, was not detected (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Figure S3). No kdr mutations were detected in the remaining sand fly species (P. sergenti, P. perfiliewi and P. caucasicus).

Table 3.

Investigation of pyrethroid resistance mechanisms in the study’s sand fly population

| Species | Resistant mutation allelic frequencies (hetero/homo), N of alleles |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kdr L1014F | Kdr L1014S | Super kdr N1575Y* | |

| Phlebotomus papatasi | 0.0% | 42.1% | 0.0% |

| (0/0) | (4/6) | (0/0) | |

| N = 38 | N = 38 | N = 16 | |

| Phlebotomus tobbi | 0.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% |

| (0/0) | (1/0) | (0/0) | |

| N = 10 | N = 10 | N = 2 | |

| Phlebotomus sergenti | 0.0% | 0.0% | N/A |

| (0/0) | (0/0) | ||

| N = 6 | N = 6 | ||

| Phlebotomus perfiliewi | 0.0% | 0.0% | N/A |

| (0/0) | (0/0) | ||

| N = 2 | N = 2 | ||

| Phlebotomus caucasicus | 0.0% | 0.0% | N/A |

| (0/0) | (0/0) | ||

| N = 2 | N = 2 | ||

N/A: not analysed; *tested only in samples with a positive kdr result

Discussion

Armenia faces a considerable risk of VBDs [1] like malaria [3], WNV disease [4, 6] and leishmaniasis [7, 8]. Unfortunately, essential information supportive of the control of corresponding disease vectors, including their resistance to insecticides, is rather limited. To address this gap, our study aimed to present initial findings on the prevalence of insecticide resistance mechanisms among the primary mosquito and sand fly vectors in Armenia.

The presence of An. sacharovi, the historically known vector of malaria in Armenia [37], was confirmed, in line with previously reported data. We investigated all known resistance mechanisms for this vector, i.e. kdr mutations associated with pyrethroid and DTT resistance and the G119S mutation associated with OP and CRB resistance, but none were detected. No data are available from previous studies in Armenia on the resistance status of An. sacharovi. Such information is limited in An. maculipennis s.l., belonging to the same species group as An. sacharovi (maculipennis group), and show evidence of phenotypic pyrethroid (alphacypermethrin and cyfluthrin) resistance [15]. Data from neighbouring countries show that resistance is established in Anopheles populations from Turkey [38, 39] and Azerbaijan [40] (including An. sacharovi and An. maculipennis s.l.) as well as in Iran [40, 41].

Both major European arboviral vectors (Cx. pipiens and Ae. albopictus) were detected. The presence of Ae. albopictus was confirmed after the first report of its introduction in Armenia [2]. Aedes albopictus is of epidemiological concern since it is a competent vector of more than 22 arboviruses, including CHIKV and DENV, and has been implicated in major arboviral outbreaks in Europe [42, 43]. Aedes albopictus mosquitoes were tested for a total of six kdr mutations linked to pyrethroid resistance (V1010G, V1010GI, I1532T, F1534C, F1534L, F1534S), and the V1016G mutation was detected, albeit at a very low frequency (1.9%; 1 heterozygote mosquito). Although no previous data are available in Armenia, the presence of V1016G mutation has been previously recorded in neighbouring countries, at a frequency of 1.0% in Georgia and 1.9% in Turkey, and this is concerning for neighbouring countries like Iran [44], where this vector is present, but also for Europe in general [45]. The occurrence of V1016G, despite its low frequency, is alarming regarding future further resistance spread. Indeed, V1016G has been shown to confer the highest levels of resistance among Ae. albopictus kdr mutations to different pyrethroids [46]. Neither chs-1 mutations (I1043L, I1043M, I1043F), linked with DFB resistance, nor CCEae3a and CCEae6a amplification events, associated with OP (tempephos) resistance, were detected in any of the specimens analysed.

Regarding Cx. pipiens, both Cx. pipiens s.s. and the anthropophilic Cx. pipiens biotype molestus were detected, in line with previous findings [2]. Culex pipiens represents the major vector for WNV, a disease with high potential to cause major outbreaks throughout Europe [47], including Armenia. The profiling of kdr mutations in Cx. pipiens mosquitoes revealed the presence of L1014F (frequency = 25.0%) in Armavir and the presence of both L1014F and L1014C (frequencies of 14.3% and 28.6%, respectively) in Ararat. This is in line with previous data showcasing the phenotypic resistance of Cx. pipiens populations from Armenia to the pyrethroid alpha-cypermethrin [15]. None of the known OP/CRB and DFB target site resistance mutations tested (G119S and I1043L/M/F, respectively) were detected in the Cx. pipiens mosquitoes that were analysed. Previously reported pyrethroid resistance records in Cx. pipiens populations in the broader region include those from Turkey [48, 49] (including the presence of the L1014C mutation [50]), Azerbaijan [40] and Iran [40]. Interestingly, diflubenzuron resistance has also been detected in Cx. pipiens from Turkey (chs-1 mutations I1043M and I1043L) [51].

Concerning Phlebotomus sand flies, the primary presence of P. papatasi, followed by P. tobbi, P. sergenti, P. perfiliewi and P. caucasicus, is shown, a finding consistent with previous studies [9]. Most of these species are confirmed vectors of Leishmania parasites [52]. Yerevan, which was the sand fly sampling area of our study, is considered a hotspot of visceral leishmaniasis, accounting for > 80.0% of cases [1]. Importantly, the kdr mutation L1014S, associated with reduced sensitivity against pyrethroids, was detected in P. papatasi and P. tobbi at frequencies of 42.1% and 10.0%, respectively. This is the first detection of resistance at the molecular level in sand flies from Armenia to our knowledge. Data from neighbouring Turkey have previously shown the occurrence of kdr mutations in P. papatasi at a close to 50.0% allelic frequency [53]. Additional studies that would also include phenotypic analyses of resistance, which seems to be established in adjacent countries like Iran [54–56] and Turkey [57], are needed to systematically monitor this phenomenon and inform vector control strategies in Armenia accordingly.

The occurrence of resistance traits that were revealed here could be due to the use of pyrethroid insecticides (cypermethrin), which are implemented in vector control programmes in Armenia [1], but it could also be related to the intense use of pesticides for agricultural purposes (including the pyrethroids lambda-cyhalothrin and deltamethrin), which has been documented in rural areas of the country [58].

Conclusion

In conclusion, molecular profiling of known vector resistance mechanisms in Armenia led to the first detection of kdr mutations associated with pyrethroid resistance in major arboviral (Ae. albopictus and Cx. pipiens mosquitoes) and leishmaniasis vectors (P. papatasi and P. tobbi sand flies) to our knowledge. The limitations of this study include the limited number of specimens per species analysed and the lack of phenotypic resistance information from the tested samples. Continuous vector resistance monitoring, a principal factor in the implementation of appropriate evidence-based control programmes, should be prioritized.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Detailed characteristics of the study’s sampling. Figure S1. Electropherograms of the COI gene region of Phlebotomus papatasi (A), P. tobbi (B), P. sergenti (C) and P. perfiliewi (D) samples. Figure S2. Electropherogram of a wild-type (part A) and a mutant (part B) Phlebotomus papatasi sand fly for the kdr L1014S mutation. Figure S3. Electropherogram of a wild-type Phlebotomus papatasi sample for the super kdr N1575Y mutation sequenced with the forward (part A) and reverse (part B) primer. Figure S4. Electropherogram of a wild-type (part A) and heterozygous (part B) Aedes albopictus sample for the kdr V1016G mutation sequenced with the reverse primer. Figure S5. Electropherogram of a wild-type Aedes albopictus sample for the kdr I1532T and F1534L/C/S mutations sequenced with the reverse primer. Figure S6. Electropherogram of a wild-type Aedes albopictus sample for the chs-1 I1043L/M/F mutations sequenced with the forward primer. Figure S7. Electropherogram of a wild-type Anopheles sacharovi sample for the kdr L1014C/F/S mutations sequenced with the forward primer. Figure S8. Electropherogram of a wild-type (part A: L1014) and four different mutants (part B: 1014F), (part C: 1014C) and heterozygous (part D: 1014L/F) and (part E: 1014L/C) Culex pipiens samples for the kdr L1014F/C/S mutations sequenced with the forward primer. Figure S9. Electropherogram of a wild-type Culex pipiens sample for the chs-1 I1043L/M/F mutations sequenced with the forward primer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: LP, KM, JV; Sample collection: LB, HV, AM; methodologies: KM, SB, HV, AM, KMP; data analysis and interpretation: KM, SB, HV, AM, KMP; writing—original draft preparation: KM, JV, SB; writing—review and editing: LP, LB, HV, AM, KMP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fondation Santé through a research grant awarded to K.M. This work received financial support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement no. 731060 (INFRAVEC2) and from the private company ECODEVELOPMENT S.A. in frame of the research programme entitled “Specialized scientific support and intelligent insect surveillance base for the Mosquito Control Programme in the Region of Central Greece”.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its additional information.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lusine Paronyan, Email: lusineparonyan@yahoo.com.

Konstantinos Mavridis, Email: konstantinos_mavridis@imbb.forth.gr.

References

- 1.Paronyan L, Avetisyan L, Gevorgyan K, Tunyan A, Manukyan A, Grigoryan A, et al. National vector control needs assessment (VCNA) in Armenia. Yerevan: Ministry of Health of Armenia Report; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paronyan L, Babayan L, Manucharyan A, Manukyan D, Vardanyan H, Melik-Andrasyan G, et al. The mosquitoes of Armenia: review of knowledge and results of a field survey with first report of Aedes albopictus. Parasite. 2020;27:42. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2020039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidyants VA, Kondrashin AV, Vanyan AV, Morozova LF, Turbabina NA, Stepanova EV, et al. Role of malaria partners in malaria elimination in Armenia. Malar J. 2019;18:178. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2814-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manukian DV, Oganesian AS, Shakhnazarian SA, Aleksanian IuT. Role of mosquitoes in the transmisson of arboviruses in Armenia. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 2006;2:38–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manukian DV, Oganesian AS, Shakhnazarian SA, Aleksanian IuT. The species composition of mosquitoes and ticks in Armenia. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 2006;1:31–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paronyan L, Zardaryan E, Bakunts V, Gevorgyan Z, Asoyan V, Apresyan H, et al. A retrospective chart review study to describe selected zoonotic and arboviral etiologies in hospitalized febrile patients in the Republic of Armenia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:445. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1764-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strelkova MV, Ponirovsky EN, Morozov EN, Zhirenkina EN, Razakov SA, Kovalenko DA, et al. A narrative review of visceral leishmaniasis in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, the Crimean Peninsula and Southern Russia. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:330. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0925-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sukiasyan A, Keshishyan A, Manukyan D, Melik-Andreasyan G, Atshemyan L, Apresyan H, et al. Re-Emerging foci of visceral leishmaniasis in Armenia—first molecular diagnosis of clinical samples. Parasitology. 2019;146:857–864. doi: 10.1017/S0031182019000064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jezek J, Manko P, Obona J. Checklist of known moth flies and sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) from Armenia and Azerbaijan. Zookeys. 2018;798:109–133. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.798.26543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chala B, Hamde F. Emerging and Re-emerging vector-borne infectious diseases and the challenges for control: a review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:715759. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.715759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson AL, Courtenay O, Kelly-Hope LA, Scott TW, Takken W, Torr SJ, et al. The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0007831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porretta D, Mastrantonio V, Lucchesi V, Bellini R, Vontas J, Urbanelli S. Historical samples reveal a combined role of agriculture and public-health applications in vector resistance to insecticides. Pest Manag Sci. 2022;78:1567–1572. doi: 10.1002/ps.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu N. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60:537–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balaska S, Fotakis EA, Chaskopoulou A, Vontas J. Chemical control and insecticide resistance status of sand fly vectors worldwide. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Control ECfDPa . Literature review on the state of biocide resistance in wild vector populations in the EU and neighbouring countries. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vontas J, Mavridis K. Vector population monitoring tools for insecticide resistance management: Myth or fact? Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2019;161:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva AP, Santos JM, Martins AJ. Mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of anophelines and their association with resistance to pyrethroids—a review. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:450. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Torres D, Chevillon C, Brun-Barale A, Berge JB, Pasteur N, Pauron D. Voltage-dependent Na+ channels in pyrethroid-resistant Culex pipiens mosquitoes. Pestic Sci. 1999;55:1012–1020. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780551010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du Y, Nomura Y, Satar G, Hu Z, Nauen R, He SY, et al. Molecular evidence for dual pyrethroid-receptor sites on a mosquito sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:11785–11790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305118110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weill M, Malcolm C, Chandre F, Mogensen K, Berthomieu A, Marquine M, et al. The unique mutation in ace-1 giving high insecticide resistance is easily detectable in mosquito vectors. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2004.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grigoraki L, Puggioli A, Mavridis K, Douris V, Montanari M, Bellini R, et al. Striking diflubenzuron resistance in Culex pipiens, the prime vector of West Nile Virus. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12103-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grigoraki L, Pipini D, Labbe P, Chaskopoulou A, Weill M, Vontas J. Carboxylesterase gene amplifications associated with insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus: geographical distribution and evolutionary origin. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fotakis EA, Chaskopoulou A, Grigoraki L, Tsiamantas A, Kounadi S, Georgiou L, et al. Analysis of population structure and insecticide resistance in mosquitoes of the genus Culex, Anopheles and Aedes from different environments of Greece with a history of mosquito borne disease transmission. Acta Trop. 2017;174:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balaska S, Fotakis EA, Kioulos I, Grigoraki L, Mpellou S, Chaskopoulou A, et al. Bioassay and molecular monitoring of insecticide resistance status in Aedes albopictus populations from Greece, to support evidence-based vector control. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:328. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kioulos I, Kampouraki A, Morou E, Skavdis G, Vontas J. Insecticide resistance status in the major West Nile virus vector Culex pipiens from Greece: resistance status of Culex pipiens from Greece. Pest Manag Sci. 2014;70:623–627. doi: 10.1002/ps.3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porretta D, Fotakis EA, Mastrantonio V, Chaskopoulou A, Michaelakis A, Kioulos I, et al. Focal distribution of diflubenzuron resistance mutations in Culex pipiens mosquitoes from Northern Italy. Acta Trop. 2019;193:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker N. Mosquitoes and their control. 2. Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fotakis EA, Mavridis K, Kampouraki A, Balaska S, Tanti F, Vlachos G, et al. Mosquito population structure, pathogen surveillance and insecticide resistance monitoring in urban regions of Crete Greece. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:e0010186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balaska S, Calzolari M, Grisendi A, Scremin M, Dottori M, Mavridis K, et al. Monitoring of insecticide resistance mutations and pathogen circulation in sand flies from Emilia-Romagna, a Leishmaniasis endemic region of Northern Italy. Viruses. 2023 doi: 10.3390/v15010148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahnck CM, Fonseca DM. Rapid assay to identify the two genetic forms of Culex pipiens L. (Diptera: Culicidae) and hybrid populations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:251–255. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.2.0750251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patsoula E, Samanidou-Voyadjoglou A, Spanakos G, Kremastinou J, Nasioulas G, Vakalis NC. Molecular and morphological characterization of Aedes albopictus in northwestern Greece and differentiation from Aedes cretinus and Aedes aegypti. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:40–54. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/43.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patsoula E, Samanidou-Voyadjoglou A, Spanakos G, Kremastinou J, Nasioulas G, Vakalis NC. Molecular characterization of the Anopheles maculipennis complex during surveillance for the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. Med Vet Entomol. 2007;21:36–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins FH, Paskewitz SM. A review of the use of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) to differentiate among cryptic Anopheles species. Insect Mol Biol. 1996;5:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1996.tb00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Djadid ND, Jazayeri H, Gholizadeh S, Rad ShP, Zakeri S. First record of a new member of Anopheles hyrcanus Group from Iran: molecular identification, diagnosis, phylogeny, status of kdr resistance and Plasmodium infection. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:1084–1093. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasai S, Ng LC, Lam-Phua SG, Tang CS, Itokawa K, Komagata O, et al. First detection of a putative knockdown resistance gene in major mosquito vector. Aedes albopictus Jpn J Infect Dis. 2011;64:217–221. doi: 10.7883/yoken.64.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romi R, Boccolini D, Hovanesyan I, Grigoryan G, Di Luca M, Sabatinell G. Anopheles sacharovi (Diptera: Culicidae): a reemerging malaria vector in the Ararat Valley of Armenia. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:446–450. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.3.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akiner MM, Caglar SS, Simsek FM. Yearly changes of insecticide susceptibility and possible insecticide resistance mechanisms of Anopheles maculipennis Meigen (Diptera: Culicidae) in Turkey. Acta Trop. 2013;126:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yavasoglu SI, Yaylagul EO, Akiner MM, Ulger C, Caglar SS, Simsek FM. Current insecticide resistance status in Anopheles sacharovi and Anopheles superpictus populations in former malaria endemic areas of Turkey. Acta Trop. 2019;193:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abadi YS, Sanei-Dehkordi A, Paksa A, Gorouhi MA, Vatandoost H. Monitoring and mapping of insecticide resistance in medically important mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Iran (2000–2020): a review. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2021;15:21–40. doi: 10.18502/jad.v15i1.6484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbasi E, Vahedi M, Bagheri M, Gholizadeh S, Alipour H, Moemenbellah-Fard MD. Monitoring of synthetic insecticides resistance and mechanisms among malaria vector mosquitoes in Iran: a systematic review. Heliyon. 2022;8:e08830. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cochet A, Calba C, Jourdain F, Grard G, Durand GA, Guinard A, et al. Autochthonous dengue in mainland France, 2022: geographical extension and incidence increase. Euro Surveill. 2022 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.44.2200818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rezza G. Chikungunya is back in Italy: 2007–2017. J Travel Med. 2018 doi: 10.1093/jtm/tay004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doosti S, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Schaffner F, Moosa-Kazemi SH, Akbarzadeh K, Gooya MM, et al. Mosquito surveillance and the first record of the invasive mosquito species Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) in Southern Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45:1064–1073. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pichler V, Caputo B, Valadas V, Micocci M, Horvath C, Virgillito C, et al. Geographic distribution of the V1016G knockdown resistance mutation in Aedes albopictus: a warning bell for Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2022;15:280. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05407-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasai S, Caputo B, Tsunoda T, Cuong TC, Maekawa Y, Lam-Phua SG, et al. First detection of a Vssc allele V1016G conferring a high level of insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus collected from Europe (Italy) and Asia (Vietnam), 2016: a new emerging threat to controlling arboviral diseases. Euro Surveill. 2019 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.5.1700847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brugman VA, Hernandez-Triana LM, Medlock JM, Fooks AR, Carpenter S, Johnson N. The role of Culex pipiens L . (Diptera: Culicidae) in Virus Transmission in Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guntay O, Yikilmaz MS, Ozaydin H, Izzetoglu S, Suner A. Evaluation of Pyrethroid susceptibility in Culex pipiens of Northern Izmir Province. Turkey J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2018;12:370–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ser O, Cetin H. Investigation of susceptibility levels of Culex pipiens L. (Diptera: Culicidae) populations to synthetic Pyrethroids in Antalya Province of Turkey. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2019;13:243–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taskin BG, Dogaroglu T, Kilic S, Dogac E, Taskin V. Seasonal dynamics of insecticide resistance, multiple resistance, and morphometric variation in field populations of Culex pipiens. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2016;129:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guz N, Cagatay NS, Fotakis EA, Durmusoglu E, Vontas J. Detection of diflubenzuron and pyrethroid resistance mutations in Culex pipiens from Mugla. Turkey Acta Trop. 2020;203:105294. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charrel RN, Gradoni L. Phlebotomine sandflies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27:123–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fotakis EA, Giantsis IA, Demir S, Vontas JG, Chaskopoulou A. Detection of pyrethroid resistance mutations in the major leishmaniasis vector Phlebotomus papatasi. J Med Entomol. 2018;55(5):1225–1230. 10.1093/jme/tjy066. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Afshar AA, Rassi Y, Sharifi I, Abai M, Oshaghi M, Yaghoobi-Ershadi M, et al. Susceptibility status of Phlebotomus papatasi and P. sergenti (Diptera: Psychodidae) to DDT and Deltamethrin in a Focus of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis after Earthquake Strike in Bam Iran. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2011;5:32–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shirani-Bidabadi L, Zahraei-Ramazani A, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Rassi Y, Akhavan AA, Oshaghi MA, et al. Assessing the insecticide susceptibility status of field population of Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in a hyperendemic area of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Esfahan Province. Central Iran Acta Trop. 2017;176:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arzamani K, Vatandoost H, Rassi Y, Abai MR, Akhavan AA, Alavinia M, et al. Susceptibility status of wild population of Phlebotomus sergenti (Diptera: psychodidae) to different imagicides in a endemic focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in northeast of Iran. J Vector Borne Dis. 2017;54:282–286. doi: 10.4103/0972-9062.217621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karakus M, Gocmen B, Ozbel Y. Insecticide susceptibility status of wild-caught sand fly populations collected from two Leishmaniasis endemic areas in Western Turkey. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2017;11:86–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tadevosyan A, Tadevosyan N, Kelly K, Gibbs SG, Rautiainen RH. Pesticide use practices in rural Armenia. J Agromedicine. 2013;18:326–333. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2013.826118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maps d-mcF. 2023. https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=4348&lang=en. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Detailed characteristics of the study’s sampling. Figure S1. Electropherograms of the COI gene region of Phlebotomus papatasi (A), P. tobbi (B), P. sergenti (C) and P. perfiliewi (D) samples. Figure S2. Electropherogram of a wild-type (part A) and a mutant (part B) Phlebotomus papatasi sand fly for the kdr L1014S mutation. Figure S3. Electropherogram of a wild-type Phlebotomus papatasi sample for the super kdr N1575Y mutation sequenced with the forward (part A) and reverse (part B) primer. Figure S4. Electropherogram of a wild-type (part A) and heterozygous (part B) Aedes albopictus sample for the kdr V1016G mutation sequenced with the reverse primer. Figure S5. Electropherogram of a wild-type Aedes albopictus sample for the kdr I1532T and F1534L/C/S mutations sequenced with the reverse primer. Figure S6. Electropherogram of a wild-type Aedes albopictus sample for the chs-1 I1043L/M/F mutations sequenced with the forward primer. Figure S7. Electropherogram of a wild-type Anopheles sacharovi sample for the kdr L1014C/F/S mutations sequenced with the forward primer. Figure S8. Electropherogram of a wild-type (part A: L1014) and four different mutants (part B: 1014F), (part C: 1014C) and heterozygous (part D: 1014L/F) and (part E: 1014L/C) Culex pipiens samples for the kdr L1014F/C/S mutations sequenced with the forward primer. Figure S9. Electropherogram of a wild-type Culex pipiens sample for the chs-1 I1043L/M/F mutations sequenced with the forward primer.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its additional information.