Abstract

Mentalization is the ability to interpret actions as caused by intentional mental states. Moreover, mentalization facilitates the development of epistemic trust (ET), namely, the ability to evaluate social information as accurate, reliable, and relevant. Recent theoretical literature identifies mentalization as a protective factor, contrasting psychopathology and emotional dysregulation. However, few investigations have explored the concurrent associations between mentalization, ET and emotion dysregulation in the context of internalizing problems in adolescence. In the present study, 482 adolescents from the general population aged between 12 and 19 were assessed with the epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire, the reflective functioning questionnaire- youth, the difficulties in emotion regulation scale, and the youth self-report. We tested the relationship between the variables through serial mediation models. Results showed that mentalization reduces internalizing problems via emotional dysregulation; ET is positively associated with mentalization but not symptomatology. Finally, both epistemic mistrust and epistemic credulity are significantly associated with internalizing symptomatology; those effects are mediated differently by difficulties in emotional regulation. In conclusion, the present study confirms mentalization’s role as a protective factor in developmental psychopathology. Nevertheless, exploring the role of the different epistemic stances guarantees a better understanding of psychopathological pathways in adolescence.

Key words: epistemic trust, mentalization, emotional dysregulation, internalizing disorders

Introduction

Internalizing problems refer to a broad range of emotional and psychological difficulties affecting an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in ways often not readily observable by others. These difficulties are characterized by emotional dysregulation, depressed mood, fear, worry, and an attitude of overcontrol (Di Pietro & Bassi, 2013; Patterson et al., 2018; Wergeland et al., 2021; Zahn-Waxler et al., 2000). This label includes some of the most common mental disorders in adolescents, such as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, social withdrawal, somatic symptoms, and related disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Costello et al., 1996). Despite each disorder’s specific trend, internalizing problems generally increase during the transition from childhood to adolescence, suggesting a possible role of puberty in activating unexpressed genetic risk (Merikangas et al., 2010; Patterson et al., 2018). In this direction, typical adolescent stage factors may contribute to its specific vulnerability: new social demands, environmental stressors, increased autonomy, specific cognitive factors, and new emotion regulation strategies (Garnefski et al., 2005; Rief & Joormann, 2019).

As aforementioned, the ability to regulate emotions plays a crucial role in the onset and progression of internalizing manifestations (Navarro et al., 2018). Emotional dysregulation is characterized by problematic patterns of emotionality in terms of intensity, duration, and frequency, negatively affecting subjective experience, behavioral responses, and physiological changes (Barnicot & Crawford, 2019; Shapero et al., 2016). Empirical literature extensively shows the relationship between emotional regulation during adolescence and the higher risk of developing internalizing disorders (Chevalier et al., 2021; Chevalier et al., 2023; Lougheed & Hollenstein, 2012; Weinberg & Klonsky, 2009).

From a psychotherapy research perspective, mentalization has gained substantial recognition for therapeutic change in various psychopathological conditions, including internalizing problems (Fischer-Kern & Tmej, 2019; Riedl et al., 2023). Indeed, mentalization is the ability to understand and interpret inner mental states related to the self and others by considering one’s thoughts, needs, emotions, and desires (Allen & Fonagy, 2008; Bateman & Fonagy, 2019). Mentalization develops in infancy through caregivers mirroring and validating a child’s emotional experiences. This intersubjective emotional attunement fosters children’s emerging ability to understand their and others’ mental states (Bateman & Fonagy, 2019; Debbanè, 2019; Midgley et al., 2019). Secure attachments promote mentalizing abilities; in contrast, difficulties in attachment experiences may promote deficits in its development, such as a lack of emotional awareness and self-reflection and difficulty distinguishing between inner mental states and external reality (Hayden et al., 2019; Parada-Fernández et al., 2021). In this direction, literature conceived mentalization as a protective function in contrast to psychopathology: it is essential for experiencing oneself as an intentional agent; it promotes the development of a stable and coherent sense of self; it enables empathy and self-awareness; it facilitates social interactions, thereby making the interpersonal relationship more predictable, secure, and meaningful; it is crucial to emotional well-being and in general for psychological health (Bateman & Fonagy, 2019; Debbanè, 2019; Fischer-Kern & Tmej, 2019; Liotti et al., 2021; Locati et al., 2022; Midgley et al., 2019; Parada-Fernández et al., 2021; Riedl et al., 2023).

One key concept associated with mentalizing is epistemic trust (ET), which is the ability to assess the trustworthiness, relevance, and general applicability of information coming from external sources (Duschinsky & Foster, 2021). The secure attachment context promotes ET’s development, encouraging individuals to be open to social learning (Milesi et al., 2023; Parolin et al., 2023). In contrast, individuals who face childhood adversities may generate higher levels of epistemic disruption, i.e., epistemic mistrust and credulity (Campbell et al., 2021). Epistemic mistrust is the tendency to suspect the reliability of incoming information, leading to resistance to the possibility of learning from others (Li et al., 2022; Rief & Joormann, 2019). Epistemic credulity is the inability to discriminate between trustworthy and untrustworthy information, making individuals more vulnerable to misinformation and exploitation (Midgley et al., 2019). Both epistemic mistrust and credulity are significant predictors of psychopathological symptoms and are associated with lower psychological well-being (Duschinsky & Foster, 2021). More specifically, epistemic mistrust is associated with general psychological vulnerability, emotional dysregulation, and distress, contributing to psychopathology (Campbell et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Liotti et al., 2023).

In the context of internalizing problems, imbalances in the direction of epistemic mistrust or credulity are sensible to distress and may hinder the development of mentalization and emotional dysregulation (Caspi et al., 2014; Fonagy & Allison, 2014; Midgley et al., 2019). More specifically, low mentalization, high epistemic mistrust, and credulity are associated with depression, anxiety, and somatization problems. Notably, epistemic mistrust was mainly associated with anxiety, whereas credulity was strongly associated with depression. Conversely, higher ET was associated with reduced depression, anxiety, and somatization (Chevalier et al., 2021; Riedl et al., 2023). Nevertheless, improvements in mentalizing are correlated with improvements in emotional regulation, depression, anxiety, somatization, cognition, mobility, self-care, social functioning, household activities, school or work activities, and social participation (Riedl et al., 2023).

Depressive disorders are associated with epistemic uncertainty and vigilance. The failure of ET’s stance, a deficit in mentalization, egocentrism, and social isolation inhibit even more mentalization abilities. Mentalization, when active, is often distorted, supporting negative cognitive bias. Difficulties in emotional regulation, limited access to regulation strategies, intolerance for negative emotional responses, and lack of impulse control may further exacerbate the situation (Belvederi Murri et al., 2017; Brumariu & Kerns, 2010; Fischer-Kern & Tmej, 2019; Midgley et al., 2019; Rief & Joormann, 2019). Moreover, anxiety disorders are characterized by epistemic vigilance or epistemic freezing, which promotes mistakes in interpreting and handling complex social situations. Anxious adolescents are more vulnerable to failures in mentalization due to difficulties in their social skills, often emphasized by their specific sensitivity to stressors and high psychological arousal (Banerjee, 2008; Chevalier et al., 2023; Midgley et al., 2019).

In this perspective, internalizing problems can be conceived as temporary or permanent disruptions of ET or the presence of pervasive forms of mistrust and credulity, vulnerabilities in mentalization and emotional regulation (Fonagy et al., 2014; Locati et al., 2023; Talia et al., 2021).

Considering this, the global aim of the present study is to explore how three epistemic stances impact internalizing problems during preadolescence and adolescence, considering the roles of mentalization and emotional dysregulation. In this direction, 4 hypotheses have been formulated: i) all variables in this study are associated (hypotheses 1); ii) ET is expected to reduce the levels of internalizing problems in adolescence and preadolescence, both directly, producing a decrease in the symptomatology, and indirectly, by promoting the development of adequate mentalization abilities and reducing emotional dysregulation (hypotheses 2); iii) epistemic mistrust is expected to lead to higher levels of internalizing problems in adolescence and preadolescence, both directly, producing an increase in symptomatology and indirectly, by reducing mentalization abilities and increasing emotional dysregulation (hypotheses 3); iv) epistemic credulity is expected to lead to higher levels of internalizing problems in adolescence and preadolescence, both directly, producing an increase in symptomatology, and indirectly, by reducing mentalization abilities and increasing emotional dysregulation (hypotheses 4).

Methods

Participants

Participants are 482 non-clinical adolescents (278 females, 58%) aged 12 to 19 years (meanage=15.6, standard deviation= 2.050). For this study, participants were recruited from secondary schools (both lower and upper secondary levels) in different regions of Italy and from sports clubs and youth centers.

Procedure

Preliminary authorization was obtained from the school authorities and the parents/legal guardians of the participants. Participation in the research was voluntary, and anonymity was ensured by assigning unique codes to each participant. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the study was conducted entirely online. Participants were contacted through an official email communication, which introduced the logic and objectives of the study and provided a link to access the actual research. Upon opening the hyperlink, participants encountered an initial interface that reiterated the critical aspects of the research. Subsequently, informed consent and consent for data processing were requested from parents and legal guardians in the case of participants who had yet to reach the legal age of consent. Afterward, preadolescents and adolescents began the data collection phase, accessing the various instruments through grouped questionnaire links. Each link required approximately 15-20 minutes to complete, with an estimated completion time of about 1 hour and 30 minutes. Questionnaires belonging to the same link had to be completed consecutively in one session, while those from different links could be completed at different times. An email address was also created and provided, allowing our research team to respond to any further questions and clarifications. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology at the University of Milano-Bicocca. The patients/participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Measures

The psychological variables in the present study, namely ET, mentalization abilities, emotional dysregulation, and cognitiveemotional- behavioral characteristics of adolescents, were investigated through self-report questionnaires. A detailed description of the instruments used is provided below.

Epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire

The epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire (ETMCQ) (Campbell et al., 2021; Liotti et al., 2023) is a self-report measure of ET composed of 15 items. Each questionnaire item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree.” The factor analysis identified 3 distinct factors: trust (epistemic trust), mistrust (epistemic distrust), and credulity (epistemic naivety or gullibility) (Campbell et al., 2021). Although this study is focused on an Italian sample, the original 3-factor English factorial solution proposed by Campbell et al. (2021) was used. This decision was made because the ongoing Italian validation of this instrument on an adolescent sample empirically supports the original English factorial structure (Campbell et al., 2021). However, the Italian validation for adults shows different results (Liotti et al., 2023).

Reflective functioning questionnaire-youth

The reflective functioning questionnaire-youth (RFQ-Y) (Duval et al., 2018; Sharp et al., 2009) is a self-report questionnaire designed for preadolescents, adolescents, and young adults aged 12 to 21. This instrument aims at the assessment of the reflective function of individuals, which is the operationalization of their mentalization abilities. The questionnaire consists of 46 items, each evaluated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. In the literature, it is recommended and supported to calculate an overall score by summing the scores from two subscales, providing a comprehensive indication of the individual’s reflective function. Higher scores in the total subscale indicate enhanced mentalization abilities. (Duval et al., 2018).

Difficulties in emotion regulation scale

The difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS) (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is one of the primary self-report tests used to assess difficulties in emotion regulation. The questionnaire consists of 36 items, each rated on a 5-point scale from 1 to 5, where 1 corresponds to “almost never” and 5 to “almost always.” In addition to an overall scale for evaluation, the items can be subdivided into 6 subscales: i) non-acceptance, difficulty in accepting emotional responses; ii) goals, experiencing difficulties in adopting goal-directed behaviors; iii) impulse, difficulties in impulse control; iv) awareness, lack of emotional awareness; v) strategies, limited access to emotion regulation strategies; vi) clarity, lack of emotional clarity. Higher scores on this instrument indicate more significant difficulties in affective regulation (Sighinolfi et al., 2010).

Youth self-report

Youth self-report (YSR/11-18) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) is a self-report instrument for adolescents aged 11-18. It aims to assess emotional competencies and behavioral aspects across various domains to comprehensively account for adolescents’ self-perception, adaptive functioning, and emotional-behavioral characteristics. The questionnaire consists of 113 items presented as statements, and respondents rate each item on a 3- point scale from 0 to 2, where 0 corresponds to “not true” and 2 corresponds to “very true or often true.” Eight subscales indicate different difficulties or problematic aspects: anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, aggressive behavior, and rule-breaking behavior. At a higher level of analysis, some of the previously mentioned subscales can be considered together, forming 2 additional clusters: internalizing manifestations (anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, and somatic complaints) and externalizing difficulties (aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors). The overall scale is the sum of the values obtained from the 8 subscales. In this instrument, higher scores indicate more significant difficulties reported (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1978).

Data analysis

To test the first hypotheses, data analyses were tested with the Statistical Manual for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 28.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) with the assistance of the PROCESS v4.1 extension for SPSS (Hayes, 2022). In hypothesis 1, Pearson correlation was employed to investigate the relationships among all variables of interest.

Subsequently, 3 serial mediation models, corresponding to the PROCESS model template number 6, were conducted to investigate hypotheses 2, 3, and 4.

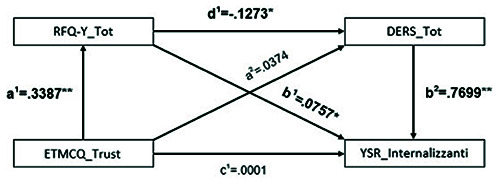

To test the second hypothesis (first serial mediation model) (Figure 1) the variables being studied are:

Independent variable: epistemic trust (ETMCQ_Trust)

Dependent variable: internalizing problems in adolescence (YSR_Internalizzanti)

Mediator 1: reflective function (RFQ-Y_Tot)

Mediator 2: Emotion dysregulation (DERS_Tot)

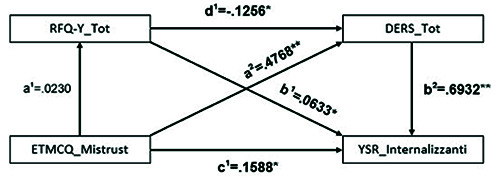

To test the third hypothesis (second serial mediation model) (Figure 2) the variables being studied are:

Independent variable: epistemic mistrust (ETMCQ_Mistrust)

Dependent variable: internalizing problems in adolescence (YSR_Internalizzanti)

Mediator 1: reflective function (RFQ-Y_Tot)

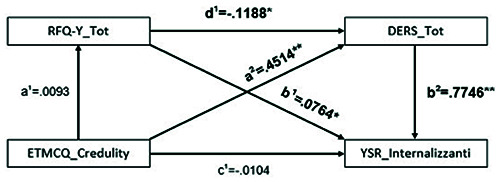

Mediator 2: emotion dysregulation (DERS_Tot) To test the fourth hypothesis (third serial mediation model) (Figure 3) the variables being studied are:

Independent variable: epistemic credulity (ETMCQ_ Credulity)

Dependent variable: internalizing problems in adolescence (YSR_Internalizzanti)

Mediator 1: reflective function (RFQ-Y_Tot)

Mediator 2: emotion dysregulation (DERS_Tot)

Unlike PROCESS, the advantage of R is that it provides secondary indirect effects. To test the secondary indirect effects in the serial mediation models investigated in hypotheses 2, 3, and 4, analyses were conducted using the ‘lavaan’ package (Rosseel, 2012) on the RStudio software (version 4.1.2) (R Core Team, 2021).

All variables investigated in this study were standardized into z-scores before conducting the analyses. Therefore, the coefficients reported for direct, indirect, and total effects are standardized.

In both R and SPSS, 95% confidence intervals were created using 1000 bootstrap samples to test the significance of direct and indirect effects. The significance level is established at the 95% confidence interval. If the confidence intervals did not include zero, it would imply a significant result.

Results

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations are presented in Table 1. The ET had a moderate, positive, and statistically significant correlation with the reflective function (r=.34, p<.001). Epistemic mistrust had a moderate, positive, and significant correlation with difficulties in emotion regulation (r=.47, p<.001) and internalizing problems (r=.49, p<.001). Epistemic credulity had a moderate, positive, and significant correlation with difficulties in emotion regulation (r=.45, p<.001) and internalizing problems (r=.34, p<.001). Both credulity and mistrust did not relate significantly to the reflective function. The reflective function had a weak, negative, and significant correlation with difficulties in emotion regulation (r=-.12, p<.005). While reflective functioning’s relationship with internalizing problems was statistically non-significant, difficulties in emotion regulation had a strong, positive, and significant correlation with internalizing problems (r=.76, p<.001).

Three serial mediation models were tested to assess the impact of ET on internalizing problems in adolescence through reflective functioning and emotion dysregulation.

Figure 1.

The first serial mediation model. The serial mediation analysis for the relationship between epistemic trust and internalizing problems in adolescence through reflective function and emotion dysregulation. *p<.05; **p<.001; ETMCQ_Trust, epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire, trust score; RFQY_ Tot, reflective functioning questionnaire-youth, overall score; DERS_Tot, difficulties in emotion regulation scale, overall scale; YSR_Internalizzanti, youth self-report, internalizing manifestations scale.

Figure 2.

The second serial mediation model. The serial mediation analysis for the relationship between epistemic mistrust and internalizing problems in adolescence through reflective function and emotion dysregulation. *p<.05; **p<.001; ETMCQ_Mistrust, epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire, mistrust score; RFQ-Y_Tot, reflective functioning questionnaire- youth, overall score; DERS_Tot, difficulties in emotion regulation scale, overall scale; YSR_Internalizzanti, youth self-report, internalizing manifestations scale.

Figure 3.

The third serial mediation model. The serial mediation analysis for the relationship between epistemic credulity and internalizing problems in adolescence through reflective function and emotion dysregulation. *p<.05; **p<.001; ETMCQ_Credulity, epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire, credulity score; RFQ-Y_Tot, reflective functioning questionnaire- youth, overall score; DERS_Tot, difficulties in emotion regulation scale, overall scale; YSR_Internalizzanti, youth self-report, internalizing manifestations scale.

Epistemic trust and internalizing problems: a serial mediation model

The model accounts for 58.5% of the variance in internalizing problems [R²=.5851, F(3,478)=224.71, p<.001]. The results showed that trust positively and significantly predicted reflective functioning [path a¹; β=.3387, t(480)=7.8874, p<.001]. The effect of trust on emotional dysregulation controlling for the reflective function is not statistically significant [path a²; β=.0374, t(479)=.7764, p=.4379]. Reflective functioning had a significative negative impact on emotion dysregulation controlling for trust [path d¹; β=-.1273, t(479)=-2.6401, p=.0086]. Reflective functioning was found to positively and significantly influence internalizing problems controlling for trust and emotion dysregulation [path b¹; β=.0757, t(478)=2.4018, p=.0167]. Emotion dysregulation positively and significantly predicted internalizing problems controlling for reflective functioning and trust [path b²; β=.7699, t(478)=25.9439, p<.001]. The direct effect, the effect of trust on internalizing problems controlling for reflective functioning and emotion dysregulation, is not statistically significant [path c¹; β=.0001, t(478)=.0018, p=.9986]. The total effect, the effect of ET on internalizing problems, is non-significant [path c; β=.0213, t(480)=.4677 p=.6402]. The outcomes of this serial mediation analysis are provided in Figure 1.

Then, we focused on the primary indirect effects. The results further showed that ET positively predicted internalizing problems via reflective functioning [path ind¹:ETMCQ_Trust→RFQY_ Tot→ YSR_Internalizzanti; β=.0257, 95% confidence interval (CI)=(.0037; .0490)]. The effect of trust on internalizing problems via emotion dysregulation was non-significant [path ind²: ETMCQ_Trust→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; β=.0288, 95% CI=(-.0485; .1043)]. Reflective functioning and emotion dysregulation serially mediated the effect of trust on internalizing problems [path ind³:ETMCQ_Trust→RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_ Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; β=-.0332; 95% CI=(-.0646; -.0048)]. The total indirect effect was statistically non-significant [β=.0213, 95% CI=(-.0564; .0950)]. The secondary indirect effects are as follows. Reflective functioning was statistically inversely related to internalizing problems via emotion dysregulation [path ind4:RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; β=-.098; 95% CI=(-.171; -.025)]. ET negatively predicts emotion dysregulation via reflective functioning [path ind5:ETMCQ_ Trust→RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot; β=-.043; 95% CI=(-.077; - .009)]. Considering these results, hypothesis 2 can be rejected.

The direct and indirect effects of ET on internalizing problems in adolescence have been shown in Table 2.

Epistemic mistrust and internalizing problems: a serial mediation model

The model explains 60.4% of the variance in internalizing problems [R²=.6045, F(3,478)=243.55, p<.001]. The results showed that the effect of mistrust on reflective functioning is not statistically significant [path a¹; β=.0230, t(480)=.5035, p=.6148]. Mistrust positively and significantly predicted emotional dysregulation, controlling for reflective function [path a²; β=.4768, t(479)=11.9704 p<.001]. Reflective functioning had a significative negative impact on emotion dysregulation controlling for mistrust [path d¹; β=-.1256, t(479)=-3.1521, p=.0017]. Reflective functioning was found to positively and significantly influence internalizing problems, controlling for mistrust and emotion dysregulation [path b¹; β=.0633, t(478)=2.1787, p=.0298]. Emotion dysregulation positively and significantly predicted internalizing problems controlling for reflective functioning and mistrust [path b²; β=.6932, t(478)=21.0044, p<.001]. The direct effect, the effect of mistrust on internalizing problems controlling for reflective functioning and emotion dysregulation, is positive and statistically significant [path c¹; β=.1588, t(478)=4.8426, p<.001]. The total effect is positive and significant; mistrust positively predicted internalizing problems in adolescence and preadolescence [path c; β=.4888, t(480)=12.2754 p<.001]. The outcomes of this serial mediation analysis are provided in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviation, and correlations among study variables (n=482).

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ETMCQ_Trust | 4.78 | 1.03 | 1 | |||||

| 2. ETMCQ_Mistrust | 4.59 | 1.04 | / | 1 | ||||

| 3. ETMCQ_Credulity | 3.50 | 1.31 | / | / | 1 | |||

| 4. RFQ-Y_Tot | 6.28 | .63 | .34** | .02 | .01 | 1 | ||

| 5. DERS_Tot | 83.30 | 24.74 | -.01 | .47** | .45** | -.12* | 1 | |

| 6. YSR_Internalizzanti | 17.97 | 10.66 | .02 | .49** | .34** | -.01 | .76** | 1 |

M, mean; SD, standard deviation; ETMCQ, epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire; RFQ-Y_Tot, reflective functioning questionnaire-youth, overall score; DERS_Tot, difficulties in emotion regulation scale, overall scale; YSR_Internalizzanti, youth self-report, internalizing manifestations scale. **p<.001; *p<.05.

Table 2.

Direct and indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals for the first serial mediation model.

| Pathway | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | .0213 | .0456 | -.0683 | .1110 |

| Direct effect | .0001 | .0313 | -.0615 | .0616 |

| Total indirect effect | .0213 | .0388 | -.0564 | .0950 |

| Primary indirect effect of M1: Ind1 | .0257 | .0116 | .0037 | .0490 |

| Primary indirect effect of M2: Ind2 | .0288 | .0390 | -.0485 | .1043 |

| Primary indirect effect of M1 and M2: Ind3 | -.0332 | .0153 | -.0646 | -.0048 |

| Secondary indirect effect of M2: Ind4 | -.098 | .037 | -.171 | -.025 |

| Secondary indirect effect of M1: Ind5 | -.043 | .017 | -.077 | -.009 |

Boot, bootstrap; SE, standard error; LLCI, lower limit of the confidence interval; ULCI, upper limit of the confidence interval; ETMCQ_Trust, epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire, trust score; RFQ-Y_Tot, reflective functioning questionnaire-youth, overall score; DERS_Tot, difficulties in emotion regulation scale, overall scale; YSR_Internalizzanti, youth self-report, internalizing manifestations scale. 1000 bootstrap samples with 95% confidence interval. Pathways are as follows: total effect of trust on internalizing problems; direct effect of trust on internalizing problems; total indirect effect of trust on internalizing problems; path ind¹: ETMCQ_Trust→RFQ-Y_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind²: ETMCQ_Trust→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind³: ETMCQ_Trust→RFQY_ Tot→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind4: RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind5: ETMCQ_Trust→RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot.

Subsequently, we shifted our focus to the primary indirect effects. The results further showed that the effect of epistemic mistrust on internalizing problems via reflective functioning was non-significant [path ind¹:ETMCQ_Mistrust→RFQ-Y_Tot→ YSR_Internalizzanti; β=.0015, 95% CI=(-.0063; .0110)]. The effect of mistrust on internalizing problems via emotion dysregulation was positive and significant [path ind²: ETMCQ_ Mistrust→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; β=.3305, 95% CI=(.2733; .3903)]. The effect of mistrust on internalizing problems via reflective functioning and emotion dysregulation was non-significant [path ind³:ETMCQ_Mistrust→RFQ-Y_Tot→ DERS_Tot→ YSR_Internalizzanti; β=-.0020; 95% CI=(-.0141; .0090)]. The total indirect effect was statistically significant [β=.3300, 95% CI=(.2730; .3898)]. Secondary indirect effects emerged as follows. Reflective functioning was statistically inversely related to internalizing problems via emotion dysregulation [path ind4:RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; β=-.087; 95% CI=(-.142; -.032)]. The effect of epistemic mistrust on emotion dysregulation via reflective functioning was statistically non-significant [path ind5:ETMCQ_Mistrust→RFQY_ Tot→DERS_Tot; β=-.003; 95% CI=(-.014; .008)]. These findings provide evidence in support of hypothesis 3.

The direct and indirect effects of epistemic mistrust on internalizing problems in adolescence have been shown in Table 3.

Epistemic credulity and internalizing problems: a serial mediation model

The model captures 58.5% of the variability in internalizing problems [R²=.5852, F(3,478)=224.7840, p<.001]. The results showed that the effect of credulity on reflective functioning is not statistically significant [path a¹; β=.0093, t(480)=.2047, p=.8379]. Credulity positively and significantly predicted emotional dysregulation controlling for reflective function [path a²; β=.4514, t(479)=11.1633 p<.001]. Reflective functioning had a significative negative impact on emotion dysregulation, controlling for credulity [path d¹; β=-.1188, t(479)=-2.9385, p=.0035]. Reflective functioning was found to positively and significantly influence internalizing problems, controlling for credulity and emotion dysregulation [path b¹; β=.0764, t(478)=2.5706, p=.0105]. Emotion dysregulation positively and significantly predicted internalizing problems controlling for reflective functioning and credulity [path b²; β=.7746, t(478)=23.2705, p<.001]. The direct effect, the effect of credulity on internalizing problems controlling for reflective functioning and emotion dysregulation, is non-significant [path c¹; β=-.0104, t(478)=-.3133, p=.7542]. The total effect is positive and significant; credulity positively predicted internalizing problems in adolescence and preadolescence [path c; β=.3392, t(480)=7.8988 p<.001]. The outcomes of this serial mediation analysis are provided in Figure 3.

Afterward, our attention turned to the primary indirect effects. The results further showed that the effect of epistemic credulity on internalizing problems via reflective functioning was non-significant [path ind¹:ETMCQ_Credulity→RFQ-Y_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; β=.0007, 95% CI=(-.0074; .0088)]. The effect of credulity on internalizing problems via emotion dysregulation was positive and significant [path ind²:ETMCQ_Credulity →DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; β=.3497, 95% CI=(.2813; .4213)]. The effect of credulity on internalizing problems via reflective functioning and emotion dysregulation was non-significant [path ind³:ETMCQ_ Credulity→RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot→ YSR_Internalizzanti; β=-.0009; 95% CI=(-.0120; .0079)]. The total indirect effect was statistically significant [β=.3495, 95% CI=(.2807; .4212)]. The following secondary indirect effects have been observed. Reflective functioning negatively predicted internalizing problems via emotion dysregulation [path ind4:RFQY_ Tot→DERS_ Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; β=-.092; 95% CI=(-.154; -.030)]. The effect of epistemic credulity on emotion dysregulation via reflective functioning was statistically non-significant [path ind5:ETMCQ_Credulity→RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_ Tot; β=-.001; 95% CI=(-.012; .010)]. The results of this study confirm the validity of hypothesis 4.

The direct and indirect effects of epistemic credulity on internalizing problems in adolescence have been shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Direct and indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals for the second serial mediation model.

| Pathway | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | .4888 | .0398 | .4106 | .5770 |

| Direct effect | .1588 | .0328 | .0944 | .2232 |

| Total indirect effect | .3300 | .0298 | .2730 | .3898 |

| Primary indirect effect of M1: Ind1 | .0015 | .0042 | -.0063 | .0110 |

| Primary indirect effect of M2: Ind2 | .3305 | .0299 | .2733 | .3903 |

| Primary indirect effect of M1 and M2: Ind3 | -.0020 | .0056 | -.0141 | .0090 |

| Secondary indirect effect of M2: Ind4 | -.087 | .028 | -.142 | -.032 |

| Secondary indirect effect of M1: Ind5 | -.003 | .006 | -.014 | .008 |

Boot, bootstrap; SE, standard error; LLCI, lower limit of the confidence interval; ULCI, upper limit of the confidence interval; ETMCQ_Mistrust, epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire, mistrust score; RFQ-Y_Tot, reflective functioning questionnaire-youth, overall score; DERS_Tot, difficulties in emotion regulation scale, overall scale; YSR_Internalizzanti, youth self-report, internalizing manifestations scale.1000 bootstrap samples with 95% confidence interval. Pathways are as follows: total effect of mistrust on internalizing problems; direct effect of mistrust on internalizing problems; total indirect effect of mistrust on internalizing problems; path ind¹: ETMCQ_Mistrust→RFQ-Y_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind²: ETMCQ_ Mistrust→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind³: ETMCQ_ Mistrust→RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot→ YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind4: RFQ-Y_Tot→ DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind5: ETMCQ_ Mistrust→RFQY_ Tot→DERS_Tot.

Discussion

The present study explores the relationship between epistemic stances (trust, mistrust, and credulity), mentalization, dysregulation, and internalizing problems in adolescence.

First, the relationship between ET and internalizing problems (Figure 1) showed a significant effect of trust in reducing emotional regulation difficulties through mentalizing abilities. Mentalization reduces internalizing symptoms by acting through emotional dysregulation. Trust has a negative serial indirect effect on internalizing problems through mentalization and emotional dysregulation. However, no direct or indirect effects of trust on internalizing problems in adolescence were shown.

Although ET plays an essential role in adolescents’ psychological well-being by promoting the development of mentalization abilities, it is not the only determinant. Emotional dysregulation and mentalization significantly influence the manifestation of internalizing symptoms. In line with the literature, these findings suggest that ET may work as a baseline, not constituting a direct protective factor for internalizing problems in adolescence (Campbell et al., 2021; Fonagy et al., 2017; Locati et al., 2022). However, results have highlighted the meaningful role of ET in fostering mentalization: ET lays the foundation for open-mindedness towards others (Locati et al., 2023; Riedl et al., 2023).

Regarding the role of mistrust in internalizing problems in adolescence (Figure 2), mistrust increases internalizing symptoms both directly and indirectly, being mediated by emotional dysregulation. Moreover, mentalization indirectly alleviates internalizing symptomatology through its influence on emotional dysregulation. An epistemic stance characterized by hypervigilance, hyperactivation, and persecution may partially generate inadequacy of interactions, anxiety states, and depressive experiences. Furthermore, the attentional diversion towards the external dimension to prevent potential environmental threats may neglect some central aspects of the intrapsychic world. This neglect may be responsible for deficits in emotional regulation skills, a diminished sense of agency, implementation of avoidance or inadequate strategies. Mistrust supports a sense of inadequacy and negative cognitive biases and promotes maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (Banerjee, 2008; Brumariu & Kerns, 2010; Chevalier et al., 2023; Locati et al., 2023; Midgley et al., 2019; Rief & Joormann, 2019).

Finally, concerning the relationship between credulity and internalizing problems (Figure 3), credulity indirectly affects internalizing problems mediated by emotional dysregulation. Moreover, mentalization indirectly mitigates internalizing symptomatology by impacting emotional dysregulation. These findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of credulity may be more prone to experiencing difficulties regulating their emotions, increasing the risk of internalizing manifestations. A possible interpretation, consistent with existing literature (Campbell et al., 2021), outlines how an incongruous and excessive level of trust in others promotes vulnerability to misinformation and dysfunctional interactions. In this direction, interpersonal interactions are characterized by a sense of betrayal and ambivalence towards an interlocutor who is considered reliable but is, in fact, inadequate and untrustworthy. The associated emotional confusion experienced and the difficulty in explaining the incongruencies of relational representations may reduce the sense of self-efficacy and agency and increase difficulties in emotion regulation (Locati et al., 2023).

Globally, mentalization has played a crucial protective role in all 3 models by significantly reducing emotional regulation difficulties and indirectly decreasing internalizing symptomatology (Locati et al., 2023). The interest in one’s and others’ mental states and the awareness of their impact on behavior facilitate a better understanding of social contexts and greater clarity regarding one’s emotions. Individuals developing mentalizing abilities become more competent in interpersonal relationships (Bateman & Fonagy, 2019; Locati et al., 2022; Locati et al., 2023). Similarly, their capacity to regulate emotions is strengthened through explicit and controlled mentalization. These abilities reduce emotional regulation difficulties and the adverse effects of stressors, increase tolerance for negative emotions, promote effective social interactions, and foster a sense of personal self-efficacy (Bradley, 2000; Lengua, 2002; Neumann et al., 2010; Parada-Fernández et al., 2021). A decrease in emotional regulation difficulties may reduce the vulnerability to internalizing problems in adolescence (Fonagy, 2015; Fonagy & Allison, 2014).

Nonetheless, in the 3 models, mentalization has a positive direct effect on symptomatology. These results, which might sound contradictory, align with literature that points out that adolescents who are good at mentalizing may be paradoxically more vulnerable to overthinking. In the case of internalizing manifestations, the ability to mentalize in some situations might enhance shame, cause problems in integrating the experience of the physical changes, and facilitate internalizing dysfunctional mechanisms (Benzi & Cipresso, 2020; Benzi et al., 2023; Chevalier et al., 2021; Locati et al., 2023).

Table 4.

Direct and indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals for the third serial mediation model.

| Pathway | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | .3392 | .0429 | .2548 | .4235 |

| Direct effect | -.0104 | .0331 | -.0753 | .0546 |

| Total indirect effect | .3495 | .0357 | .2807 | .4212 |

| Primary indirect effect of M1: Ind1 | .0007 | .0039 | -.0074 | .0088 |

| Primary indirect effect of M2: Ind2 | .3497 | .0356 | .2813 | .4213 |

| Primary indirect effect of M1 and M2: Ind3 | -.0009 | .0049 | -.0120 | .0079 |

| Secondary indirect effect of M2: Ind4 | -.092 | .031 | -.154 | -.030 |

| Secondary indirect effect of M1: Ind5 | -.001 | .005 | -.012 | .010 |

Boot, bootstrap; SE, standard error; LLCI, lower limit of the confidence interval; ULCI, upper limit of the confidence interval; ETMCQ_Credulity, epistemic trust mistrust credulity questionnaire, credulity score; RFQ-Y_Tot, reflective functioning questionnaire-youth, overall score; DERS_Tot, difficulties in emotion regulation scale, overall scale; YSR_Internalizzanti, youth self-report, internalizing manifestations scale. 1000 bootstrap samples with 95% confidence interval. Pathways are as follows: total effect of credulity on internalizing problems; direct effect of credulity on internalizing problems; total indirect effect of credulity on internalizing problems; path ind¹: ETMCQ_Credulity→RFQ-Y_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind²: ETMCQ_ Credulity→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind³: ETMCQ_ Credulity→RFQY_ Tot→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind4: RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot→YSR_Internalizzanti; path ind5: ETMCQ_ Credulity→RFQ-Y_Tot→DERS_Tot.

Finally, difficulties in emotional regulation have proven in all models to have unquestionable relevance concerning internalizing manifestation in adolescence. Restricted access to emotional regulation strategies, intolerance for negative affectivity, ineffectiveness in organizing goal-directed behaviors, low perception of self-efficacy, and difficulties in restoring emotional homeostasis are central and distinctive elements responsible for the origin and maintenance of internalizing problems (Barnicot & Crawford, 2019; Navarro et al., 2018; Weinberg & Klonsky, 2009).

In conclusion, this research has contributed to a deeper comprehension of the relationship between the 3 epistemic stances, mentalization, emotional regulation processes, and mental health outcomes. These findings confirm the validity of the tripartite model of ET and provide evidence that the constructs of trust, mistrust, and epistemic credulity are a theoretical framework able to explain and predict various trajectories of ontogenetic development. From a diagnostic and therapeutic standpoint, they suggest that some treatment approaches, such as therapeutic assessment and mentalization-based treatment, may be relevant in reactivating ET, mentalization, and the underlying mechanisms of social learning. These approaches have demonstrated effectiveness in treating a wide range of psychopathologies, including the internalizing manifestations (Bateman & Fonagy, 2019; Kamphuis & Finn, 2019; Li et al., 2022; Locati et al., 2023).

Further research is needed to delve deeper into the complex interplay between these variables and better understand the underlying mechanisms involved.

The present study has some limitations. Although the sample size for analysis was adequate, expanding the numerosity of the sample is needed. Moreover, the exclusive use of technological means for data collection, mainly determined by the need to overcome the difficulties and limitations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, brought both negative and positive aspects. On the one hand, the research may have been disadvantaged as the online mode automatically precluded the use of certain types of tools and interviewer-participant direct interaction. On the other hand, it allowed our research team to reach many adolescents from different regions of Italy, enabling us to analyze a large and representative sample while optimizing administration. Another limitation, as mentioned earlier, can be identified in the sole use of self-report measures for data collection. These questionnaires are particularly susceptible to biases such as social desirability bias. In the end, though an Italian validation of the ETCMQ for adults (Liotti et al., 2023) has been recently published, in this study we used the English factorial solution for the abovementioned reasons; this could represent a further limitation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study explores the complex relationship between epistemic stances, mentalization, emotional dysregulation, and internalizing problems in adolescence.

This study highlights the distinct impacts of mistrust and credulity in fostering internalizing problems. Mistrust exacerbates the symptomatology through both direct and indirect pathways. On the contrary, credulity primarily operates through mediating mechanisms, mainly via emotional dysregulation, which has been proven to be one of the main factors responsible for the onset and maintenance of internalizing manifestations.

Furthermore, the findings underline ET’s importance in promoting adequate mentalization skills. Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge that ET cannot guarantee adolescents’ psychological well-being and prevent the onset of emotional and psychological difficulties. Mentalization confirmed its protective role, decreasing vulnerability to internalizing issues by significantly reducing emotion dysregulation. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the interactive pathways through which different epistemic stances influence adolescent mental health outcomes. Further research is warranted to deepen our understanding of these complex dynamics and inform more effective prevention and treatment strategies.

Funding Statement

Funding: the present work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Achenbach T. M., Edelbrock C. S. (1978). The classification of child psychopathology: a review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychological Bulletin, 85(6), 1275-1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. M., Rescorla L. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: an integrated system of multiinformant assessment. Aseba. [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. G., Fonagy P. (2008). La mentalizzazione: psicopatologia e trattamento. Il mulino. [Book in Italian]. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R. (2008). Social cognition and anxiety in children. In Sharp C., Fonagy P., Goodyer I. (Eds.), Social Cognition and Developmental Psychopathology (pp. 239-269). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnicot K., Crawford M. (2019). Dialectical behaviour therapy v. mentalization-based therapy for borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine, 49, 2060-2068. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718002878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Fonagy P. (2019). Mentalizzazione e disturbi di personalit→. Una guida pratica al trattamento. Raffaello Cortina Editore. [Book in Italian]. [Google Scholar]

- Belvederi Murri M., Ferrigno G., Penati S., Muzio C., Piccinini G., Innamorati M., Ricci F., Pompili M., Amore M. (2017). Mentalization and depressive symptoms in a clinical sample of adolescents and young adults. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 22(2), 69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzi I. M. A., Cipresso P. (2020). Let’s dive into it! Exploring mentalizing abilities in adolescence in an immersive 360° environment. Annual Review of CyberTherapy and Telemedicine, 18, 271-274. [Google Scholar]

- Benzi I. M. A., Fontana A., Barone L., Preti E., Parolin L., Ensink K. (2023). Emerging personality in adolescence: developmental trajectories, internalizing and externalizing problems, and the role of mentalizing abilities. Journal of Adolescence, 95(3), 537-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley S. J. (2000). Affect regulation and the development of psychopathology. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu L. E., Kerns K. A. (2010). Parent-child attachment and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a review of empirical findings and future directions. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 177-204. doi: 10.1017/ S0954579409990344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C., Tanzer M., Saunders R., Booker T., Allison E., Li E., O’Dowda C., Luyten P., Fonagy P. (2021). Development and validation of a self-report measure of epistemic trust. PLoS One, 16(4), 0250264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone. 0250264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A., Houts R. M., Harrington H., Israel S., Meier M. H., Shalev I., Moffitt T. E., Belsky D. W., Goldman-Mellor S. J., Ramrakha S., Poulton R. (2014). The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science, 2(2), 119-137. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier V., Simard V., Achim J. (2023). Meta-analyses of the associations of mentalization and proxy variables with anxiety and internalizing problems. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 95, 102694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier V., Simard V., Achim J., Burmester P., Beaulieu- Tremblay T. (2021). Reflective Functioning in Children and Adolescents With and Without an Anxiety Disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 698654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E. J., Angold A., Burns B. J., Stangl D. K., Tweed D. L., Erkanli A., Worthman C. M. (1996). The great smoky mountains study of youth: goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53(12), 1129-1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996. 01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro M., Bassi E. (2013). L’intervento cognitivo comportamentale per l’et→̀ evolutiva: strumenti di valutazione e tecniche per il trattamento. Erickson. [Book in Italian]. Debbanè, M. (2019). Mentalizzazione: dalla teoria alla pratica clinica. Edra. [Book in Italian]. [Google Scholar]

- Duschinsky R., Foster S. (2021). Mentalizing and epistemic trust: the work of Peter Fonagy and colleagues at the Anna Freud Centre. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duval J., Ensink K., Normandin L., Sharp C., Fonagy P. (2018). Measuring reflective functioning in adolescents: relations to personality disorders and psychological difficulties. Adolescent Psychiatry, 8(1), 5-20. doi: 10.2174/22106766 08666180208161619. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Kern M., Tmej A. (2019). Mentalization and depression: theoretical concepts, treatment approaches and empirical studies - an overview. Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie, 65(2), 162-177. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2019.65.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P. (2015). Mutual regulation, mentalization, and therapeutic action: a reflection on the contributions of Ed Tronick to developmental and psychotherapeutic thinking. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 35(4), 355-369. doi: 10.1080/07351690.2015.1022481. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Allison E. (2014). The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 372-380. doi: 10.1037/a0036505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Campbell C., Bateman A. (2017). Mentalizing, attachment, and epistemic trust in group therapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 67(2), 176-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Luyten P., Campbell C., Allison L. (2014). Epistemic trust, psychopathology and the great psychotherapy debate. Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy. Available from: http://www.societyforpsychotherapy.org/epistemic-trust-psychopathology-and-the-great-psychotherapydebate. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N., Kraaij V., van Etten M. (2005). Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Adolescence, 28(5), 619-631. doi: 10.1016/j. adolescence.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K. L., Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41-54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.000000 7455.08539.94. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M. C., Mullauer P. K., Gaugeler R., Senft B., Andreas S. (2019). Mentalization as mediator between adult attachment and interpersonal distress. Psychopathology, 52(1), 10-17. doi: 10.1159/000496499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis third edition: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis J. H., Finn S. E. (2019). Therapeutic assessment in personality disorders: toward the restoration of epistemic trust. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101(6), 662-674. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2018.1476360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua L. J. (2002). The contribution of emotionality and selfregulation to the understanding of children’s responses to multiple risks. Child Development, 73(1), 144-161. doi: 10.1111/ 1467-8624.00397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E. T., Midgley N., Luyten P., Sprecher E. A., Campbell C. (2022). Mapping the journey from epistemic mistrust in depressed adolescents receiving psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 69(5), 678-690. doi: 10.1037/cou 0000625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotti M., Milesi A., Spitoni G. F., Tanzilli A., Speranza A. M., Parolin L., Campbell C., Fonagy P., Lingiardi V., Giovanardi G. (2023). Unpacking trust: the Italian validation of the epistemic trust, mistrust, and credulity questionnaire (ETMCQ). PLoS One, 18(1), e0280328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotti M., Spitoni G. F., Lingiardi V., Marchetti A., Speranza A. M., Valle A., Jurist E., Giovanardi G. (2021). Mentalized affectivity in a nutshell: validation of the Italian version of the brief-mentalized affectivity scale (B-MAS). PLoS One, 16(12), e0260678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locati F., Benzi I. M. A., Milesi A., Campbell C., Midgley N., Fonagy P., Parolin L. (2023). Associations of mentalization and epistemic trust with internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence: a gender_sensitive structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Adolescence, 95(8), 1564-1577. doi: 10.1002/jad.12226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locati F., Milesi A., Conte F., Campbell C., Fonagy P., Ensink K., Parolin L. (2022). Adolescence in lockdown: the protective role of mentalizing and epistemic trust. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 969-984. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lougheed J. P., Hollenstein T. (2012). A limited repertoire of emotion regulation strategies is associated with internalizing problems in adolescence. Social Development, 21(4), 704-721. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00663.x. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., He J., Burstein M., Swanson S. A., Avenevoli S., Cui L., Swendsen J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the national comorbidity study adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980-989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley N., Ensink K., Lindqvist K., Malberg N., Muller N. (2019). Il trattamento basato sulla mentalizzazione per bambini: un approccio time-limited. Raffaello Cortina Editore. [Book in Italian]. [Google Scholar]

- Milesi A., De Carli P., Locati F., Benzi I., Campbell C., Fonagy P., Parolin L. (2023). How can I trust you? The role of facial trustworthiness in the development of epistemic and interpersonal trust. Human Development, 67(2), 57-68. doi.org/10.1159/000530248 [Google Scholar]

- Navarro J. Vara MD.,Cebolla, A., Baños R. (2018). Validación psicométrica del cuestionario de regulación emocional (ERQ-CA) en población adolescente española. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 5(1), 9-15. doi: 10.21134/rpcna.2018.05.1.1. [Article in Spanish]. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann A., van Lier P. A. C., Gratz K. L., Koot H. M. (2010). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents using the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Assessment, 17(1), 138-149. doi: 10.1177/ 1073191109349579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parada-Fernández P., Herrero-Fernández D., Oliva-Macías M., Rohwer H. (2021). Analysis of the mediating effect of mentalization on the relationship between attachment styles and emotion dysregulation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(3), 312-320. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolin L., Zucchelli C., Locati F. (2023). Lo sviluppo della mentalizzazione in et→ evolutiva. La relazione tra attaccamento e fiducia epistemica. Psicologia Clinica dello Sviluppo, 1, 31-50. doi: 10.1449/106173. [Article in Italian]. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson M. W., Mann F. D., Grotzinger A. D., Tackett J. L., Tucker-Drob E. M., Harden K. P. (2018). Genetic and environmental influences on internalizing psychopathology across age and pubertal development. Developmental Psychology, 54(10), 1928-1939. doi: 10.1037/dev0000578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core Team. (2021). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Riedl D., Rothmund M. S., Grote V., Fischer M. J., Kampling H., Kruse J., Nolte T., Labek K., Lampe A. (2023). Mentalizing and epistemic trust as critical success factors in psychosomatic rehabilitation: results of a single center longitudinal observational study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 1150422. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1150422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rief W., Joormann J. (2019). Revisiting the cognitive model of depression: the role of expectations. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 1(1), 1-19. doi: 10.32872/cpe.v1i1.32605. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. (2012). Lavaan: an r package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1-36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero B. G., Abramson L. Y., Alloy L. B. (2016). Emotional reactivity and internalizing symptoms: moderating role of emotion regulation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(3), 328-340. doi: 10.1007/s10608-015-9722-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C., Williams L. L., Ha C., Baumgardner J., Michonski J., Seals R., Patel A. B., Bleiberg E., Fonagy P. (2009). The development of a mentalization-based outcomes and research protocol for an adolescent inpatient unit. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 73(4), 311-338. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2009.73.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sighinolfi C., Pala A. N., Chiri L. R., Marchetti I., Sica C. (2010). Difficulties in emotion regulation scale (ders): traduzione e adattamento italiano. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale, 16(2), 141-170. [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Duschinsky R., Mazzarella D., Hauschild S., Taubner S. (2021). Epistemic trust and the emergence of conduct problems: aggression in the service of communication. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 710011. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021. 710011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A., Klonsky E. D. (2009). Measurement of emotion dysregulation in adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 616-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wergeland G. J. H., Riise E. N., Öst L. G. (2021). Cognitive behavior therapy for internalizing disorders in children and adolescents in routine clinical care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101918. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C., Klimes-Dougan B., Slattery M. J. (2000). Internalizing problems of childhood and adolescence: prospects, pitfalls, and progress in understanding the development of anxiety and depression. Development and Psychopathology, 12(3), 443-466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]