Abstract

A crucial point for the understanding of the link between attachment and emotion regulation concerns the individual tendency in turning to others to alleviate distress. Most previous studies in this field have considered almost exclusively intra-personal forms of emotion regulation, neglecting the role of social interaction in emotion regulation processes. In the present study, instead, we focused on interpersonal emotion regulation. 630 adults were assessed for their attachment orientations, general difficulties in emotion regulation, and habitual intra-personal and interpersonal emotion regulation strategies. Results showed that the imbalance between the hyper-activation and deactivation of the attachment system, which characterize unsecure attachment, reflects a correspondent imbalance in the use of emotion regulation strategies, with an exaggerated dependence on other associated with attachment anxiety and pseudo-autonomy associated to attachment avoidance.

Key words: attachment, emotion regulation, interpersonal, avoidance, anxiety

Introduction

According to attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Bowlby, 1980), when facing physical or psychological threats, individuals may activate their attachment system turning to internalized representations of attachment figures or to actual supportive others to alleviate their distress. This emotion-regulatory function of attachment has led to the conceptualization of attachment theory as an emotion-regulation theory (Mikulincer et al., 2003; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2007; Schore & Schore, 2008). According to this view, secure attachment facilitates the flexibility and effectiveness of emotion regulation processes, whereas different forms of attachment insecurity may interfere with the effectiveness of emotion regulation. Namely, individuals with avoidant attachment inhibit or block the activation of the attachment system, to keep attachment needs and tendencies deactivated, leading to the inhibition or suppression of the emotional experience (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). Individuals with anxious attachment, instead, tend to hyperactivate the attachment system resulting in the chronic intensification of emotions that demand attention and care (e.g., jealousy and anger) or that emphasize a person’s vulnerability and neediness (e.g., sadness, anxiety, fear, and shame) (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), as an ineffective way to attract the attention of the attachment figure (real or internalized). Thus, the hyperactivation of the attachment system, associated with attachment anxiety, and the deactivation of the attachment system, connected with attachment avoidance, are crucial to understanding individual differences in emotion regulation (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2008).

Several studies have consistently reported that adult individuals with secure attachment are more likely to have adaptive and effective patterns of emotion regulation, in terms of beliefs, expectations, and perceptions about threatening events (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Moreover, secure people are more inclined to rely on their ability to manage and cope effectively with stress (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Concerning the appraisal patterns of stressful events, secure people perceive life adversities with more hope and optimism (Blake & Norton, 2014) and show higher negative mood regulation expectancies, i.e., positive beliefs regarding their ability to alleviate or terminate a negative mood state (Thorberg & Lyvers, 2010). They also tend to use more beneficial and effective emotion-regulation strategies, such as problem-focused coping, reappraisal, and actual support-seeking behavior, and are more self-confident in their capacity to deal with challenges and threats (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019; Tanzilli et al., 2021). Such aptitude to positively reappraise and manage stressful events seems to encourage securely attached individuals to remain open to their emotions and to express and communicate their feelings to others, accurately, freely, and without distortions (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). Avoidance of attachment, instead, is related with distancing coping, in which individuals engage in thoughts or behaviors that distract or disengage them from the stressor (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), such as stress denial and disengagement (e.g., Holmberg et al., 2011), with suppression of unwanted thoughts (Fraley & Shaver, 1997; Gillath et al., 2005), repression (e.g., Mikulincer & Orbach, 1995), and withdrawal from situations that make one feel vulnerable (Fraley et al., 1998; Fraley & Shaver, 2016). On the other hand, individuals with an anxious attachment tend to exaggerate the negative appraisal of threatening and stressful events and sense them in more catastrophic ways (Mikulincer & Florian, 1998) and experience emotional overload facing normative life stressors (Taubman Ben-Ari et al., 2009). There is evidence that people with anxious attachment perceive themselves as less able to cope effectively with life stressors and threats (for a review: Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). All these findings are consistent with the evidence of a wide range of mental health impairments associated with attachment- related emotion regulation difficulties (Calvo et al., 2022; Malik et al., 2015; Mortazavizadeh et al., 2018; Cortés-García et al., 2019; Messina et al., 2023b).

In the field of emotion regulation, research in the past decade has been focused on two emotion regulation strategies with different adaptive values: reappraisal (i.e., reframing an emotional situation as less emotional) and suppression (i.e., inhibiting outward expression when emotionally aroused) (Gross, 1998). Empirical comparisons have revealed that reappraisal is associated with a more positive expression of emotions, better interpersonal functioning, and well-being when compared to suppression (Gross, 2002; Gross & John, 2003). Moreover, reappraisal has been shown to be positively linked with mental health, and negatively with emotional disorders (Aldao et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2014; Joormann & Gotlib, 2010), whereas suppression is negatively related to mental health indicators (Hu et al., 2014), and its habitual use has been observed in patients with depression and anxiety diagnoses (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010).

Despite the link between attachment orientations and difficulties in emotion regulation has been widely described, the evidence coming from empirical studies that have specifically investigated the relationship between anxious and avoidant attachment and the use of adaptive/maladaptive emotion regulation strategies is surprisingly scant. In line with these findings, individuals with insecure attachment orientations would be expected to use less cognitive reappraisal and more suppression. Some studies have indeed reported that both attachment avoidance and anxiety show less use of reappraisal and more of suppression (Brenning et al., 2012; Read et al., 2018). However, the most consistent results view different insecure attachment dimensions as inclined to different habitual use of emotion regulation strategies, with higher utilization of suppression and lower of reappraisal in avoidant individuals, and with less use of reappraisal without preference for suppression in anxious individuals (Vrtička et al., 2012; Garrison et al., 2014; Troyer & Greitemeyer, 2018). Finally, in other cases, avoidant attachment demonstrated not only more use of suppression, but also of reappraisal (Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012), whilst the preference for anxious attachment seems to vary in the use of suppression depending on relational context (Winterheld, 2016). Thus, the association between attachment orientations and emotion regulation appears to be not completely understood.

A crucial missing point for the understanding of the link between attachment and emotion regulation concerns the interpersonal component of emotion regulation. Most of the results coming from the studies described above, indeed, have taken into consideration only intra-personal features of emotion regulation, neglecting all the interpersonal strategies by which individuals may rely on others to regulate their emotions (e.g., seeking reassurance). This is in line with the majority of research in the field of emotion regulation, where prominent models recognize the importance of interpersonal processes in emotion regulation (Gross et al. 2006; Campos et al. 2011), but, in fact, have been mainly focused on intra-personal processes. In this regard, attachment research may take advantage of a recent line of investigation that has taken into consideration interpersonal emotion regulation (IER) (Niven et al., 2017; Zaki & Williams, 2013; Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2018; Grecucci et al., 2015; Grecucci et al., 2021; Messina et al., 2021). IER is defined as a set of regulatory processes that are located in the interpersonal extremity of the intra-personal versus interpersonal continuum of emotion regulation (Campo et al., 2017), and occur during live social interactions (Zaki & Williams, 2013; Niven et al., 2017). Early empirical investigations have been addressed to the identification of relevant IER strategies. Starting from responses by hundreds of participants to open-ended questions about the way they use others to regulate emotions, Hofmann et al. (2016), have identified the following most usual ways to regulate emotions interpersonally: enhancing positive affect, which describes a tendency to seek out others to increase feelings of happiness and joy; perspective taking, which involves the use of others to be reminded not to worry and that others might have worse situations; soothing, which consists of seeking out others for comfort and sympathy; and social modeling, which concerns looking to others to see how they might cope with a given situation. In another study, Dixon-Gordon et al. (2018) have focused on a theory-based identification of clinically relevant IER strategies leading to the identification of Reassurance- seeking and Venting as IER strategies and proved their relevance in predicting psychiatric symptoms and clinically relevant behaviors in daily life. The investigation of individual differences in the use of such strategies in association with attachment orientations may shed light on a crucial missing point for the understanding of the link between attachment and emotion regulation.

The goals of the present study are to examine to what extent attachment orientations are predicted by: i) general emotion regulation difficulties (o dysregulation); ii) habitual use of traditionally- investigated intra-personal emotion regulation strategies (reappraisal and suppression); and more importantly; iii) to investigate, for the first time, to what extent attachment orientations are predicted by the habitual use of interpersonal emotion regulation strategies identified in the IER literature. Based on the previous considerations, we hypothesized that individuals with higher levels of avoidant attachment may be inhibited in the use of IER strategies (corresponding to attachment system deactivation) whereas individuals with higher levels of anxious attachment may excessively depend on IER strategies to regulate their emotional states (corresponding to attachment system hyper-activation).

Methods

Participants and recruitment

The sample consisted of 630 volunteer participants (496 females), with an age range between 18 and 80 years (M=41.01, SD=13.86). Inclusion criteria included; i) age 18 and older; ii) Italian speakers; and iii) valid responses (no missing data in the questionnaires). The questionnaires were prepared using Google Forms and disseminated through different social media (Facebook and WhatsApp), without a specific target. We used a snowball sampling strategy: the links were initially shared on social media and participants were encouraged to pass them on to others, with a focus on recruiting the general public. This study received approval from the Ethical Committee for Psychological Research at the University of Padua [Protocol number: 3995]. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The demographic characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1.

Instruments

Experiences in Close Relationships - Revised questionnaire

The ECR-R (Fraley et al., 2000; Italian version: Busonera et al., 2014; Calvo, 2008) consists of 36 items, scored on a Likert scale from 1 to 7, assessing two insecure orientations of adult attachment: i) Attachment Anxiety, which describes the individual’s sensitivity to issues relating to rejection, loss, fear of being abandoned, and tendency to use hyperactivating strategies in attachment- related experiences (example item: “I’m afraid that I will lose my partner’s love”); and ii) Attachment Avoidance, which encompasses discomfort with intimacy, dependence, and closeness, and a propensity of the person to use attachment deactivating strategies (e.g., “I prefer not to show a partner how I feel deep down”). Higher scores indicate greater degrees of anxiety and/or avoidance, and consequently lower levels of attachment security. Good internal consistencies have been reported for both the Attachment Anxiety (α=0.90) and Attachment Avoidance (α=0.89) subscales (Busonera et al., 2014).

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale

The DERS (Gratz & Roemer 2004; Italian version: Giromini et al., 2012) is a 36-item self-report measure that assesses the following dimensions of emotion regulation difficulties: lack of emotional awareness (awareness; e.g. “When I’m upset I take time to figure out what I’m really feeling”), lack of emotional clarity (Clarity; e.g. “I am confused about how I feel”), difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed (impulsivity; e.g. “When I’m upset, I lose control over my behaviors”), difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when distressed (goals; e.g. “When I’m upset, I have difficulty getting work done”), non-acceptance of negative emotional responses (non-acceptance; e.g. “When I’m upset, I become irritated with myself for feeling that way”), and limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies (strategies; e.g. “When I’m upset, I believe that there is nothing I can do to make myself feel better”). For each item participants are instructed to rate the frequency of the emotion regulation features described in each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“almost never”) to 5 (“almost always”), with high scores representing increased difficulties with emotion regulation. The DERS demonstrates high internal consistency for all subscales (α ranging from 0.76 to 0.94) (Giromini et al., 2012).

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

The ERQ (Gross & John, 2003; Italian version: Balzarotti et al., 2010) consists of 10 items describing strategies to regulate positive and negative emotions and participants are instructed to rate their agreement with the use of such strategies ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly agree”). The ERQ allows the evaluation of two sub-scales: Reappraisal (e.g., “When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation”) and Suppression (e.g. “When I am feeling negative emotions, I make sure not to express them”). High internal consistency has been showed for both the Reappraisal (α=0.84 reappraisal) and Suppression (α=0.72) subscales (Balzarotti et al., 2010).

Interpersonal Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

The IERQ (Hofmann et al., 2016; Italian version: Messina et al., 2022b) consists of 20 items that describe examples of interpersonal emotion regulation strategies, and participants are asked to rate how much the item is true for them on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not true for me at all”) to 5 (“extremely true for me”). It allows the assessment of 4 subscales: Enhancing Positive Affect, which describes a tendency to share emotions with others to increase feelings of happiness and joy (e.g. “I like being around others when I’m excited to share my joy”); Perspective Taking, which regards the use of others to be reminded not to worry and that others may have it worse (e.g. “Having people remind me that others are worse off helps me when I’m upset”); Soothing, which consists of seeking out comfort and sympathy from other (e.g. “I look for other people to offer me compassion when I’m upset”); and Social Modelling, which involves looking to others to see how they might cope with a given situation (e.g. “It makes me feel better to learn how others dealt with their emotions’’). Each item of the questionnaire describes examples of the listed IER strategies, and participants are asked to rate how much the item is true for them on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not true for me at all”) to 5 (“extremely true for me”). The Italian version of the questionnaire showed good psychometric properties, with high Cronbach alpha coefficients for all subscales (α’s between .78 and .85) (Messina et al., 2022b).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants (N=630).

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 496 | 78.73 |

| Male | 133 | 21.11 |

| Other | 1 | 0.16 |

| Age | ||

| <20 | 35 | 5.56 |

| 21-30 | 142 | 22.54 |

| 31-40 | 142 | 22.54 |

| 41-50 | 134 | 21.27 |

| 51-60 | 127 | 20.16 |

| 61-70 | 41 | 6.51 |

| >70 | 9 | 1.43 |

| Education | ||

| Graduate degree | 96 | 15.24 |

| University graduate | 219 | 34.76 |

| High school graduate | 281 | 44.60 |

| Secondary school graduate | 34 | 5.40 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 159 | 25.24 |

| Relationship without cohabitation | 117 | 18.57 |

| Relationship and cohabitation | 354 | 56.19 |

Difficulties in Interpersonal Emotion Regulation

The DIRE (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2018; Italian version: Messina et al., 2022a) evaluates clinically relevant difficulties in interpersonal emotion regulation. The DIRE is a scenariobased measure, in which participants are invited to score the likelihood that in each scenario they would respond in ways described in each of the 21 items. First, three scenarios are presented: i) feeling upset about a time-sensitive project that needs to be completed for school or work; ii) fighting with a significant other, and iii) thinking that friends have been avoiding you; for each scenario individuals are asked to rate how distressed they would feel in that scenario on a scale of 0 (“not at all distressed”) to 100 (“extremely distressed”). Then, participants are asked to indicate, ranging from 1 (“very unlikely”) to 5 (“very likely”), the likelihood that they would respond in each of the ways described in each item. The DIRE allows the assessment of 2 intra-personal emotion regulation factors: Avoid (e.g., “Distract yourself from how you are feeling” and Accept (“Simply notice your feelings’’); and two interpersonal factors: Vent (e.g., “Raise your voice or criticize your friends to express how you feel”) and Reassurance-seek (e.g., “Keep asking for reassurance”). Good internal consistencies have been reported for all subscales of the Italian version of the questionnaire (Venting: α=.76, Reassurance-seeking: α=.87, Avoidance: α=.72, Acceptance: α=.71) (Messina et al., 2022b).

Data analyses

First, to verify the association between attachment orientations (assessed with the ECR-R) and general difficulties in emotion regulation (assessed with the DERS), we carried out two simple regressions with total DERS scores as predictors of ECR-R scores of Attachment Anxiety (ANS) and Attachment Avoidance (AV). To further investigate the association between attachment orientations and specific difficulties in emotion regulation, we also tested all DERS subscales (Nonacceptance; Goals; Impulse; Awareness; Strategies; Clarity) as predictors in multiple regression analyses with ANS and AV as dependent variables. Due to the significant association between ANS and AV, in all multiple regressions of this study when we tested the effects on each attachment orientation we controlled for the other.

Second, to verify the association between attachment orientations and habitual use of intra-personal emotion regulation strategies, we tested ERQ subscales of Reappraisal and Suppression as predictors in multiple regression analyses with ANS and AV as dependent variables.

Third, to verify the association between attachment orientations and habitual use of interpersonal emotion regulation strategies, we tested IERQ subscales Enhancing Positive Affect (EPA), Perspective Taking (PT), Soothing (S), and Social Modelling (SM) as predictors in multiple regression analyses with ANS and AV as dependent variables.

Finally, to verify the association between attachment orientations and difficulties in interpersonal emotion regulation, we considered all DIRE subscales: two intra-personal (Accept and Avoid) and two interpersonal (Reassurance-seek and Vent) as predictors, with ANS and AV as dependent variables. In this latter analysis, we added the covariate DIRE Distress obtained by the subjective rating of the scenarios used in the questionnaire.

Results

Attachment predicted by general difficulties in emotion regulation

As expected, attachment anxiety (ANS) (r=.505, p<.001) and attachment avoidance (AV) (r=.205, p<.001) were predicted by total scores of difficulties in regulating emotions. Moreover, AV was predicted by lower scores of DERS Goals (fewer difficulties in regulating emotions in line with personal goals), but by higher scores of DERS Clarity (more difficulties related to the clarity of emotional experiences). Instead, ANS was predicted by higher scores in DERS Impulse (more difficulties related to impulse regulation) and DERS strategies (more difficulties in using strategies to regulate emotions) (Table 2).

Attachment predicted by habitual use of reappraisal and suppression

Both ANS and AV were associated with less use of Reappraisal as a strategy to regulate emotion. Moreover, AV was also significantly related to more use of Suppression as a strategy to regulate emotions (Table 3).

Attachment predicted by habitual use of interpersonal emotion regulation strategies

AV was predicted by higher scores in PT, whereas it was negatively associated with all the other forms of interpersonal regulation, with significant negative effects in the case of EPA and SM subscales. ANS, instead, was associated with more frequent use of most IER strategies (including EPA, S, and SM), except for PT which showed a negative association with ANS (Table 4).

Attachment predicted by difficulties in interpersonal emotion regulation

Individual differences in attachment orientations (ANS and AV) resulted significantly predicted by difficulties in emotion regulation limited to the interpersonal component of regulation, whereas difficulties related to intra-personal strategies did not affect attachment orientations. The subscale Reassurance-Seek emerged as very significant in distinguishing individual differences in attachment, with a negative association with AV and a positive association with ANS. Moreover, attachment anxiety was also predicted by the use of Vent to regulate emotions (Table 5).

Discussion

Individual differences in attachment orientations can be crucial for the understanding of emotion regulation. The hyperactivation of the attachment system, associated with attachment anxiety, and the deactivation of the attachment system, typical of attachment avoidance, may influence the ways individuals regulate their emotions, especially if we consider interpersonal forms of emotion regulation in which individuals turn to others to achieve the regulation purposes. In the present study, we investigated attachment orientations in association with emotion regulation, considering not only intra-personal forms of regulation but also interpersonal emotion regulation (IER), a missing point for a broader understanding of the link between these constructs.

As expected, we confirmed that insecure attachment orientations can significantly be predicted by general difficulties in emotion regulation and individual differences in intra-personal emotion regulation, and, for the first time, we have also shed light on IER attachment-related differences.

Table 2.

Results of the multiple regressions examining the association between attachment orientations (ECR-R) and general difficulties in emotion regulation (DERS).

| R2 | B | SE B | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECR-R avoidance | 0.17 | <.001 | |||

| DERS non-acceptance | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.40 | .684 | |

| DERS goals | -0.64 | 0.24 | -2.60 | .010** | |

| DERS impulse | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.78 | .437 | |

| DERS awareness | 0.34 | 0.31 | 1.10 | .270 | |

| DERS strategies | .0.28 | 0.19 | -1.48 | .140 | |

| DERS clarity | 1.14 | 0.22 | 5.21 | <.001*** | |

| ECR-R anxiety | 0.30 | 0.04 | 7.70 | <.001*** | |

| ECR-R anxiety | 0.32 | <.001 | |||

| DERS non-acceptance | 0.25 | 0.16 | 1.59 | .112 | |

| DERS goals | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.86 | .393 | |

| DERS impulse | 0.50 | 0.21 | 2.44 | .015* | |

| DERS awareness | -0.04 | 0.30 | -0.12 | .905 | |

| DERS strategies | 0.78 | 0.18 | 4.27 | <.001*** | |

| DERS clarity | 0.33 | 0.22 | 1.51 | .130 | |

| ECR-R avoidance | 0.29 | 0.04 | 7.70 | <.001*** |

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001; SE, standard error.

Table 3.

Results of the multiple regressions examining the association between attachment orientations (ECR-R) and emotion regulation strategies (ERQ).

| R2 | B | SE B | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECR-R avoidance | 0.16 | <.001*** | |||

| IERQ enhancing positive affect | -0.59 | 0.20 | -2.94 | .003** | |

| IERQ perspective taking | 0.64 | 0.22 | 2.87 | .004** | |

| IERQ soothing | -0.17 | 0.22 | -0.78 | .435 | |

| IERQ social modeling | -0.81 | 0.25 | -3.18 | .002** | |

| ECR-R anxiety | 0.36 | 0.03 | 10.49 | <.001*** | |

| ECR-R anxiety | 0.20 | <.001*** | |||

| IERQ enhancing positive affect | 0.46 | 0.21 | 2.25 | 0.032* | |

| IERQ perspective taking | -0.62 | 0.24 | -2.65 | .008** | |

| IERQ soothing | 0.94 | 0.23 | 4.12 | <.001*** | |

| IERQ social modeling | 0.61 | 0.27 | 2.25 | .024* | |

| ECR-R avoidance | 0.41 | 0.04 | 10.49 | <.001*** |

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001; SE, standard error.

Table 4.

Results of the multiple regressions examining the association between attachment orientations (ECR-R) and use of interpersonal emotion regulation strategies (IERQ).

| R2 | B | SE B | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECR-R avoidance | 0.19 | <.001*** | |||

| ERQ reappraisal | -0.27 | 0.12 | -2.33 | .020* | |

| ERQ suppression | 1.08 | 0.15 | 7.22 | <.001** | |

| ECR-R anxiety | 0.28 | 0.03 | 8.54 | <.001 | |

| ECR-R anxiety | 0.13 | <.001** | |||

| ERQ reappraisal | -0.36 | 0.13 | -2.68 | .007* | |

| ERQ suppression | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.03 | .304 | |

| ECR-R avoidance | 0.36 | 0.04 | 8.54 | <.001** |

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001; SE, standard error.

Concerning intra-personal emotion regulation, we confirmed the literature reporting more difficulties in regulating emotions associated with both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (for systematic reviews see: Mortazavizadeh & Forstmeier, 2018; Malik et al., 2015), together with specific difficulties linked with each attachment orientation (when controlling for the other). Attachment anxiety resulted from a specific impairment in the use of cognitive strategies to regulate emotions together with a specific difficulty in impulse control. This pattern of emotion regulation difficulties associated with attachment anxiety has been largely documented in previous studies (Goodall et al., 2012; Marganska et al., 2013; Velotti et al., 2016), and supports the hypothesis of impairments in the cognitively-mediated abilities to down-regulate negative emotional activation, resulting in the maintenance of dysregulated emotional state (Frederickson et al., 2018; Grecucci et al., 2020), corresponding to the well-described overreactions typical of anxious attachment (Mikulincer et al., 2003). Attachment avoidance, instead, was predicted by fewer difficulties in using cognitive strategies to regulate emotions, but with specific impairment concerning the clarity of mental representations of emotional states (also reported in Marganska et al., 2013; Morel & Papouchis, 2015). Even if the control of emotion is often considered in its adaptive functions (Ochsner & Gross, 2005), considering the general difficulty in regulating emotions and the specific lack of emotional clarity also observed in attachment avoidance, the higher recruitment of cognitive strategies in association with avoidance may reflect maladaptive recruitment of control-based cognitive strategies (Messina et al., 2016; Grecucci et al., 2020; Hoorelbeke et al., 2016) or defensive emotional control (Horowitz, 1998). In sum, the imbalance between the hyper-activation/deactivation of the attachment system observed respectively in attachment anxiety/avoidance seems to reflect a correspondent imbalance in emotion regulation, with the maintenance of dysregulated states in association with anxiety and an over-control of emotion (with the relative absence of emotional clarity) in association with avoidance.

Accounting for this hypothesis, we also observed a corresponding pattern of differences in the use of suppression and reappraisal associated with attachment orientations. In attachment anxiety, the observation of less habitual use of reappraisal is consistent with the difficulty in cognitive down-regulation of emotional states and the relative chronic dysregulation. In attachment avoidance, we observed a clear preference for suppression, confirming a clear trend in emotion regulation and attachment research (Vrtička et al., 2012; Garrison et al., 2014; Troyer & Greitemeyer, 2018), but also reduced use of reappraisal. This result, again, is compatible with the interpretation of the defensive use of maladaptive cognitive strategies associated with avoidance.

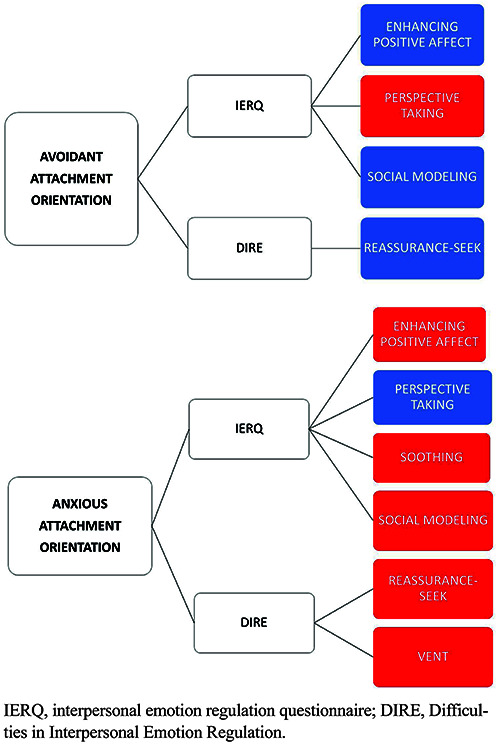

Going beyond intra-personal emotion regulation, the hypothesized imbalance between dysregulation/over-regulation respectively associated with attachment anxiety and avoidance seems to correspond also to specific preferences for IER (Figure 1). Attachment anxiety was predicted by the proneness in using IER strategies, including seeking out others to increase feelings of happiness and joy (enhancing positive affect), seeking out others for comfort and sympathy (soothing), and looking to others to see how they might cope with a given situation (social modeling). Moreover, attachment anxiety showed to be connected with more difficulties related to exaggerated use of others to obtain reassurance (reassurance- seek) or for venting their negative emotional states. Attachment avoidance, instead, was predicted by less use of interpersonal strategies to regulate emotions, less use of enhancing positive affect, and social modeling strategies. An exception in this trend was the strategy of using others to be reminded not to worry and that others have it worse (perspective taking), which resulted to be more associated with attachment avoidance and less with attachment anxiety. This finding is in line with the general differences in the use of cognitive strategies associated with avoidance and anxiety, especially if we consider that in the first validation study of the IERQ, the subscale Perspective Taking of the IERQ resulted associated with denial (Hofmann et al. 2016). In terms of difficulties, avoidance was significantly associated with less reassurance-seeking in case of distress, extending current studies which have also repeatedly shown a link between avoidant attachment and inhibition of support and proximity seeking when dealing with stressful conditions (Hart et al., 2005).

The findings of the present study may also contribute, more in general, to the understanding of the nature of IER. In this regard, contrasting hypotheses have been provided in the literature. On one hand, early models of IER have started from the hypothesis of a positive adaptive value of IER as a mediator factor in the widely described negative association between depression and social support (Marroquín, 2001; Christensen and Haynos, 2020). Subsequent contributions, instead, have observed negative consequences of IER in perpetuating psychopathological symptoms, such as exaggerated dependency on others to regulate one’s own emotions (Hoffman, 2014). Moreover, previous studies have observed that interpersonal emotion regulation is associated with self-reported psychopathology (Messina et al., 2022a; Messina et al., 2022b; Dixon-Gordon et al., 2018; Messina et al., 2023a). The results of the present study, and more generally the consideration of the attachment theory perspective, conciliate these views affirming that both exaggerate dependency on others to regulate emotions and the pseudo-autonomy of avoidant individuals may lead to emotional disorders. Future studies with clinical samples may contribute to a deep understanding of the possible role of IER as a mediator of the association between attachment and emotional disorders and understanding its role in attachment-related interpersonal processes in psychotherapy settings (Talia et al., 2019; Talia et al., 2022; Armusewicz et al., 2022).

Table 5.

Results of the multiple regressions examining the association between attachment orientations (ECR-R) and clinically-relevant interpersonal emotion regulation strategies (DIRE).

| R2 | B | SE B | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECR-R avoidance | 0.14 | <.001*** | |||

| DIRE acceptance | -0.42 | 0.85 | -0.49 | .622 | |

| DIRE avoidance | 1.48 | 0.98 | 1.52 | .130 | |

| DIRE reassurance-seek | -3.15 | 0.86 | -3.68 | <.001*** | |

| DIRE vent | 1.60 | 1.04 | 1.55 | .123 | |

| DIRE distress | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.50 | .619 | |

| ECR-R anxiety | 0.34 | 0.04 | 9.45 | <.001*** | |

| ECR-R anxiety | 0.22 | <.001*** | |||

| DIRE acceptance | -0.10 | 0.88 | -0.31 | .913 | |

| DIRE avoidance | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.11 | .266 | |

| DIRE reassurance-seek | 3.64 | 0.88 | 4.12 | <.001*** | |

| DIRE vent | 3.75 | 1.07 | 3.52 | <.001*** | |

| DIRE distress | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.64 | .009** | |

| ECR-R avoidance | 0.37 | 0.04 | 9.45 | <.001*** |

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001; SE, standard error.

The findings of the present study should be interpreted considering its limitations. First, our sample was mainly composed of female participants (78.73%). The over-representation of female participants has been observed in a range of other psychological studies employing online surveys and online recruitment methods (Whitaker et al., 2017), suggesting that the over-representation of females may not be due to the specific issues or variables investigated in the present study. Nevertheless, the generalization of our findings remains somewhat problematic. Second, this study relied entirely on self-report measures. Especially in the case of attachment assessment, individual biases associated with attachment avoidance (e.g., minimization of distress/dependency) and anxiety (e.g., exaggeration of emotional distress/dependency) may systematically influence their responses in self-report assessments of emotional/relational functioning (Jacobvitz et al., 2002). Future studies will likely benefit from data collected with other methods, such as direct observation and coding of attachment and interpersonal regulation constructs. A third limitation concerns the instruments used to evaluate IER. The IERQ is a data-driven instrument (Hofmann et al., 2016), the DIRE seems to assess clinically relevant dimensions (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2018) and, on the whole, both instruments have shown excellent psychometric characteristics (see also Messina et al., in 2022a; Messina et al., 2022b). At the same time, due to the novelty of the IER field of investigation, such instruments may not cover all relevant dimensions of interpersonal influences in emotion regulation. More studies in this field are strongly required. Finally, although this sample had the benefit of being a large community sample, it was composed of relatively non-clinical participants. The replication of the present findings in clinical samples and the analyses of possible moderation of the association between attachment and psychopathology due to IER variables may help in a deep understanding of the nature of IER.

IERQ, interpersonal emotion regulation questionnaire; DIRE, Difficulties in Interpersonal Emotion Regulation.

Figure 1.

Dysregulation/over-regulation respectively associated with attachment anxiety and avoidance.

Conclusions

The consideration of IER has enlarged the previous state of the art of attachment and emotion regulation research. Attachment orientations were significantly predicted by individual differences in emotion regulation. The hyperactivation of the attachment system, peculiar to attachment anxiety, was reflected in the recruitment of others to regulate personal emotions. Attachment anxiety, in particular, was associated with impaired self-regulation, which leads to dysregulated states, and an exaggerated dependency on others to regulate emotions. Instead, the deactivation of the attachment system, a typical feature of the avoidant style of attachment, was reflected in a pseudo-autonomy in emotion regulation. Attachment avoidance was associated with a preference for intra-personal maladaptive/defensive cognitive-control strategies to over-regulate emotions, with a higher risk of isolation in case of distress and lack of clarity about emotional states. The investigation of IER appears to be a very promising trail for understanding the links between attachment and emotion regulation.

Funding Statement

Funding: none.

References

- Armusewicz K., Steele M., Steele H., Murphy A. (2022). Assessing therapist and clinician competency in parent-infant psychotherapy: The REARING coding system (RCS) for the group attachment based intervention (GABI). Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 25(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarotti S., John O.P., Gross J.J. (2010). An Italian Adaptation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 61-67. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel A.L., Hay A., Doan S.N., Hofmann S.G. (2018). Interpersonal emotion regulation: a review of social and developmental components. Behaviour Change, 35(4), 203-216. [Google Scholar]

- Blake J., Norton C.L. (2014). Examining the Relationship between Hope and Attachment: a meta-analysis. Psychology, 5(06), 556-565. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.56065 [Google Scholar]

- Brenning K.M., Soenens B., Braet C., Bosmans G.U.Y. (2012). Attachment and depressive symptoms in middle childhood and early adolescence: Testing the validity of the emotion regulation model of attachment. Personal relationships, 19(3), 445-464. [Google Scholar]

- Busonera A., Martini P.S., Zavattini G.C., Santona A. (2014). Psychometric Properties of an Italian Version of the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R) Scale. Psychological Reports, 114(3), 785-801. doi: 10.2466/03.21. PR0.114k23w9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo V. (2008). Il questionario ECR-R: aspetti di validazione della versione italiana dello strumento [The ECR-R questionnaire: Aspects of validation of the Italian version of the instrument]. X Congresso Nazionale della Sezione di Psicologia Clinica e Dinamica dell’Associazione Italiana di Psicologia (AIP), Padova, 12-14 Sep. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo V., D’Aquila C., Rocco D., Carraro E. (2022). Attachment and well-being: Mediatory roles of mindfulness, psychological inflexibility, and resilience. Current Psychology, 41, 2966-2979. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00820-2 [Google Scholar]

- Campos J.J., Walle E.A., Dahl A., Main A. (2011). Reconceptualizing emotion regulation. Emotion Review, 3(1), 26-35. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. (1994). Emotion regulation: influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2-3), 228-249. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01287.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-García L., Takkouche B., Seoane G., Senra C. (2019). Mediators linking insecure attachment to eating symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one, 14(3), e0213099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K.A., Haynos A.F. (2020). A theoretical review of interpersonal emotion regulation in eating disorders: enhancing knowledge by bridging interpersonal and affective dysfunction. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8, 1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon K.L., Bernecker S.L., Christensen K. (2015). Recent innovations in the field of interpersonal emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 36-42. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon K.L., Haliczer L.A., Conkey L.C., Whalen D.J. (2018). Difficulties in interpersonal emotion regulation: Initial development and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(3), 528-549. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R.C., Davis K.E., Shaver P.R. (1998). Dismissingavoidance and the defensive organization of emotion, cognition, and behavior. In Simpson J. A., Rholes W. S. (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 249-279). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R.C., Shaver P.R. (1997). Adult Attachment and the Suppression of Unwanted Thoughts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(5), 1080-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R.C., Shaver P.R. (2016). Attachment, Loss, and Grief. Bowlby’s Views, New Developments, and Current Controversies. In Cassidy J., Shaver P. R. (Eds.), Handbook of Attachment. Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications (3rd ed., pp. 40-62). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R.C., Waller N.G., Brennan K.A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 350-365. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson J.J., Messina I., Grecucci A. (2018). Dysregulated anxiety and dysregulating defenses: Toward an emotion regulation informed dynamic psychotherapy. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison A.M., Kahn J.H., Miller S.A., Sauer E.M. (2014). Emotional avoidance and rumination as mediators of the relation between adult attachment and emotional disclosure. Personality and Individual Differences, 70, 239-245. [Google Scholar]

- Gillath O., Bunge S.A., Shaver P.R., Wendelken C., Mikulincer M. (2005). Attachment-style differences in the ability to suppress negative thoughts: Exploring the neural correlates. NeuroImage, 28(4), 835-847. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giromini L., Velotti P., De Campora G., Bonalume L., Cesare Zavattini G. (2012). Cultural adaptation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: Reliability and validity of an Italian version. Journal of clinical psychology, 68(9), 989-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall K., Trejnowska A., Darling S. (2012). The relationship between dispositional mindfulness, attachment security and emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(5), 622-626. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K.L., Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment, 26(1), 41-54. [Google Scholar]

- Grecucci A., Messina I., Amodeo L., Lapomarda G., Crescentini C., Dadomo H., Frederickson J. (2020). A dual route model for regulating emotions: Comparing models, techniques and biological mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grecucci A., Messina I., Monachesi B. (2021). La ricerca sulla regolazione emozionale: stato dell’arte e sviluppi futuri. Giornale italiano di psicologia, 48(3), 733-760. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J.J., John O.P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyurak A., Goodkind M.S., Kramer J.H., Miller B.L., Levenson R.W. (2012). Executive functions and the down-regulation and up-regulation of emotion. Cognition & emotion, 26(1), 103-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J., Shaver P. R., Goldenberg J. L. (2005). Attachment, Self-Esteem, Worldviews, and Terror Management: Evidence for a Tripartite Security System. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 999–1013. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S.G. (2014). Interpersonal emotion regulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Cognitive therapy and research, 38(5), 483-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S.G., Carpenter J.K., Curtiss J. (2016). Interpersonal emotion regulation questionnaire (IERQ): Scale development and psychometric characteristics. Cognitive therapy and research, 40(3), 341-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg D., Lomore C. D., Takacs T.A., Price E.L. (2011). Adult attachment styles and stressor severity as moderators of the coping sequence. Personal Relationships, 18(3), 502–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01318.x [Google Scholar]

- Hoorelbeke K., Koster E.H., Demeyer I., Loeys T., Vanderhasselt M.A. (2016). Effects of cognitive control training on the dynamics of (mal) adaptive emotion regulation in daily life. Emotion, 16(7), 945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M.J. (1998). Cognitive psychodynamics: From conflict to character. John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz D., Curran M., Moller N. (2002). Measurement of adult attachment: The place of self-report and interview methodologies. Attachment & Human Development, 4(2), 207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreman A., Vingerhoets A.J. (2012). Attachment and wellbeing: The mediating role of emotion regulation and resilience. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(7), 821-826. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S., Folkman S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Malik S., Wells A., Wittkowski A. (2015). Emotion regulation as a mediator in the relationship between attachment and depressive symptomatology: A systematic review. Journal of affective disorders, 172, 428-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marganska A., Gallagher M., Miranda R. (2013). Adult attachment, emotion dysregulation, and symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(1), 131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroquín B. (2011). Interpersonal emotion regulation as a mechanism of social support in depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(8), 1276-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina I., Calvo V., Masaro C., Ghedin S., Marogna C. (2021). Interpersonal Emotion Regulation: From Research to Group Therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 636. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina I., Maniglio R., Spataro P. (2023a). Attachment insecurity and depression: The mediating role of interpersonal emotion regulation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1-11. [Google Scholar]

- Messina I., Spataro P., Grecucci A., Marogna C., Dixon-Gordon K. L. (2022a). Difficulties in interpersonal regulation of emotions (DIRE) questionnaire: Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version and Associations with psychopathological symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina I., Spataro P., Grecucci A., Moskow D.M., Marogna C., Hofmann S.G. (2022b). Interpersonal emotion regulation questionnaire: psychometric properties of the Italian version and associations with psychopathology. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 25(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina I., Spataro P., Sorella S., Grecucci A. (2023b). “Holding in Anger” as a Mediator in the Relationship between Attachment Orientations and Borderline Personality Features. Brain Sciences, 13(6), 878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Florian V. (1998). The relationship between adult attachment styles and emotional and cognitive reactions to stressful events. In Simpson J. A., Rholes W. S. (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 143-165). Guilford Press. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0146167295214011 [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Orbach I. (1995). Attachment styles and repressive defensiveness: The accessibility and architecture of affective memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(5), 917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Shaver P.R. (2008). Adult attachment and affect regulation. In Cassidy J., Shaver P. R. (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 503–531). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R. (2016). Attachment in Adulthood, Second Edition: Structure, Dynamics, and Change. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Shaver P.R. (2019). Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel K., Papouchis N. (2015). The role of attachment and reflective functioning in emotion regulation. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 63(4), NP15-NP20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavizadeh Z., Forstmeier S. (2018). The role of emotion regulation in the association of adult attachment and mental health: A systematic review. Archives of Psychology, 2(9). [Google Scholar]

- Niven K. (2017). The four key characteristics of interpersonal emotion regulation. Current opinion in psychology, 17, 89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner K.N., Gross J.J. (2005). The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(5), 242-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read D.L., Clark G.I., Rock A.J., Coventry W.L. (2018). Adult attachment and social anxiety: the mediating role of emotion regulation strategies. PloS One, 13(12), e0207514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver P.R., Mikulincer M. (2007). Adult attachment strategies and the regulation of emotion. Handbook of emotion regulation, 446, 465. [Google Scholar]

- Schore J.R., Schore A.N. (2008). Modern attachment theory: the central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clinical social work journal, 36(1), 9-20. [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Georg A., Siepe B., Gullo S., Miller-Bottome M., Volkert J., Taubner S. (2022). An exploratory study on how attachment classifications manifest in group psychotherapy. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 25(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Taubner S., Miller-Bottome M. (2019). Advances in research on attachment-related psychotherapy processes: seven teaching points for trainees and supervisors. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 22(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzilli A., Di Giuseppe M., Giovanardi G., Boldrini T., Caviglia G., Conversano C., Lingiardi V. (2021). Mentalization, attachment, and defense mechanisms: a Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual-2-oriented empirical investigation. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 24(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubman Ben-AriO., Shlomo S.B., Sivan E., Dolizki M. (2009). The transition to motherhood - a time for growth. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(8), 943-970. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.8.943 [Google Scholar]

- Thorberg F.A., Lyvers M. (2010). Attachment in relation to affect regulation and interpersonal functioning among substance use disorder in patients. Addiction Research & Theory, 18(4), 464-478. doi: 10.3109/16066350903254783 [Google Scholar]

- Troyer D., Greitemeyer T. (2018). The impact of attachment orientations on empathy in adults: Considering the mediating role of emotion regulation strategies and negative affectivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 198-205. [Google Scholar]

- Velotti P., D’Aguanno M., De Campora G., Di Francescantonio S., Garofalo C., Giromini L., Zavattini G.C. (2016). Gender moderates the relationship between attachment insecurities and emotion dysregulation. South African Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 191-202. [Google Scholar]

- Vrtička P., Sander D., Vuilleumier P. (2012). Influence of adult attachment style on the perception of social and non-social emotional scenes. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(4), 530-544. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker C., Stevelink S., Fear N. (2017). The use of Facebook in recruiting participants for health research purposes: a systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research, 19(8), e290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams W.C., Morelli S.A., Ong D.C., Zaki J. (2018). Interpersonal emotion regulation: Implications for affiliation, perceived support, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(2), 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterheld H.A. (2016). Calibrating use of emotion regulation strategies to the relationship context: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality, 84(3), 369-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talia A., Georg A., Siepe B., Gullo S., Miller-Bottome M., Volkert J., Taubner S. (2022). An exploratory study on how attachment classifications manifest in group psychotherapy. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 25(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J., Williams W.C. (2013). Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion, 13(5), 803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]