Abstract

Infections caused by Cryptococcus gattii mainly affect immunocompetent individuals and the treatment presents important limitations. This study aimed to validate the efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), fluoxetine hydrochloride (FLH), and paroxetine hydrochloride (PAH) in vitro against C. gattii. The antifungal activity of SSRI using the microdilution method revealed a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 31.25 µg/ml. The combination of FLH or PAH with amphotericin B (AmB) was analyzed using the checkerboard assay and the synergistic effect of SSRI in combination with AmB was able to reduce the SSRI or AmB MIC values 4–8-fold. When examining the effect of SSRI on the induced capsules, we observed that FLH and PAH significantly decreased the size of C. gattii capsules. In addition, the effects of FLH and PAH were evaluated in biofilm biomass and viability. The SSRI were able to reduce biofilm biomass and biofilm viability. In conclusion, our results indicate the use of FLH and PAH exhibited in vitro anticryptococcal activity, representing a possible future alternative for the cryptococcosis treatment.

Keywords: Cryptococcus gattii, Biofilm, Antifungal, Serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were active against Cryptococcus gattii and in combination with amphotericin B (AmB) exhibited a synergistic effect. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) also reduced capsule size and biofilm, suggesting their potential in cryptococcosis treatments.

Introduction

According to the Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections (GAFFI), mycoses globally affect >300 million people, and ∼25 million are at serious risk of death (Rodrigues and Nosanchuk 2020). Aspergillus spp., Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., and Paracoccidioides spp. are the main ones responsible for invasive fungal diseases (Gow et al. 2022).

Cryptococcus gattii, an emerging fungal pathogen, has demonstrated a notable potential to cause infections in immunocompetent individuals (Springer and Chaturvedi 2010). The treatment of cryptococcosis involves the antifungals amphotericin B (AmB) and fluconazole (Flz). Amphotericin B (AmB), introduced in the late 1950s, has long been considered the gold standard for severe cases (Saag et al. 2000). Fluconazole, a triazole antifungal agent, is used for both induction and maintenance therapy (Perfect et al. 2010). Conventional treatments for cryptococcosis face challenges such as fungal resistance development, notable host toxicity, and limited central nervous system (CNS) penetration for certain medications (Zhai et al. 2012). Consequently, there is a pressing need for the development of alternatives to address systemic mycoses treatment.

Fluoxetine hydrochloride (FLH) and paroxetine hydrochloride (PAH), both from the class of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) drugs, have received approval as antidepressants for the management of depression and anxiety disorders (Cruz et al. 2020, Murphy et al. 2021). The antifungal potential of SSRI against Cryptococcus neoformans has recently been demonstrated at fungicidal concentrations below 10 µg/ml (Pereira et al. 2021) and further, these drugs can act synergistically or additively with Flz in vivo, reducing the fungal burden in the brain, kidney, and spleen (Zhai et al. 2012). In this study, we aimed to investigate in vitro and biofilm antifungal effects of FLH and PAH against C. gattii.

Materials and methods

Strains and growth conditions

Cryptococcus gattii ATCC 56990 and C. gattii clinical isolate 5 (C. gattii 5) obtained from the collection from the Oral Microbiology and Immunology Laboratory of the Institute of Science and Technology of São José dos Campos/UNESP were used. Both strains were maintained in Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) at 37°C. For the assays, yeasts were grown in Sabouraud broth (Difco Laboratories) incubated at 37°C (150 rpm) for 48 h.

Drugs and antifungals

The SSRI drugs FLH (Fagron, Bologna, Italy), PAH (Infinity Pharma, Hong Kong, China), and the antifungal AmB (Sigma–Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) were used in this study. A fresh solution of each drug was prepared before each assay using a maximum concentration of 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma–Aldrich) as a co-solvent to maximize solubility. The intermediate solution was prepared in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma–Aldrich) for the assays.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

To evaluate the antifungal activity of the SSRI drugs the broth microdilution assay was performed according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (Arendrup et al. 2017). Fluoxetine hydrochloride (FLH) and PAH at concentrations from 1.95 to 1000 µg/ml, and AmB at concentrations from 0.03 to 8 µg/ml were prepared. Then, C. gattii (2.5 × 105 cells/ml) were added to 96-well plates containing the drugs for treatment and incubated for 48 h for 37ºC. Spectrophotometric readings at 530 nm were performed and the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest drug concentration that did not allow fungal growth. The minimal fungicidal concentration (MFC) was determined by transferring an inoculum from the wells of microdilution assay to SDA plates using sterile wood picks and further incubation at 37ºC for 48 h. The MFC was defined as the lowest drug concentration that did not permit visual growth of any fungal colonies.

Evaluation of synergistic effects of the SSRI drugs with AmB

The synergistic effects of SSRI drugs and AmB were assessed using the checkerboard assay, based on the broth microdilution method as described in previous studies (Odds 2003, Arendrup et al. 2017). Concentrations of FLH and PAH ranging from 0.97 to 500 µg/ml, and AmB at concentrations ranging from 0.06 to 8 µg/ml were used. Cryptococcus gattii suspensions at 5 × 105 cells/ml were used and subsequently, the plates were incubated at 37ºC for 48 h. Spectrophotometric readings at 530 nm were conducted. To assess synergistic activity, the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) was determined using the formula: ΣFIC = FICA + FICB, where FIC represents the ratio of the MIC of the drug in combination with the MIC when used alone. Next, FICI was categorized as follows: “synergistic effect” if FICI is ≤ 0.5 and “indifferent” if FICI is > 1 and ≤ 4, and “antagonistic“ relationship was defined as FIC index > 4.0 (Odds 2003).

Analyses of capsule size

Cryptococcus gattii capsules were induced, according to Zaragoza and Casadevall (2004). For this, C. gattii at 5 × 106 cells/ml was inoculated in the induction medium (10% Sabouraud broth in 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.4) and incubated for 24 h at 30ºC. Subsequently, cells with induced capsules were removed from the induction medium and treated with subinhibitory drug concentrations (sub-MIC: FLH and PAH = 15.6 µg/ml and AmB = 0.25 µg/ml) in RPMI. The untreated cells were used as the control. The treatment was performed for 24 h at 37ºC. Cells were stained with India ink and analyzed with optical microscopy Axioplan 2 (Zeiss, Germany). Capsule size was measured using the ImageJ software (Rueden et al. 2016) by calculating the difference between the whole cell and the cell body size.

Biofilm formation and treatment

Biofilm formation was performed as described by Martinez and Casadevall (2006). For biofilm preadhesion, 100 µL of 108 cells/ml of C. gattii prepared in RPMI medium supplemented with 2% glucose was added to 96-well plates and incubated at 37ºC without agitation for 24 h. The wells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove nonadherent yeasts. Subsequently, 100 µL of the medium was added to the wells and the plate was incubated at 37ºC for 48 h without agitation. After this, wells were washed with PBS to remove nonadherent yeasts. Adherent fungal cells were considered mature biofilms. To evaluate the susceptibility of C. gattii biofilms to FLH and PAH, biofilms were treated with 10x of SSRI drugs MIC (312.5 µg/ml), 20 × SSRI drugs MIC (625 µg/ml), or AmB 10x MIC (5 µg/ml) and incubated at 37ºC for 24 h.

Effect of SSRI drug treatment on C. gattii biofilms biomass

Effects of SSRI drug treatment on C. gattii biofilms biomass were analyzed using the crystal violet method according to Peeters et al. (2008). After treatments, wells with biofilms were washed with PBS and fixed with absolute ethanol for 15 min. Next, 100 µL of 0.5% crystal violet was added to each well and incubated for 20 min. The excess dye was removed and the wells were washed with PBS. Further, 100 µL of absolute ethanol was added to dilute the dye. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm and the results were expressed as a percentage reduction. Cryptococcus gattii biofilms formed after 48 h without treatment were used as the control and the corresponding absorbance values were representative of 100% biomass.

Effect of SSRI drug treatment on biofilm cell viability

Biofilms were formed as described above, and the effect of SSRI drugs on C. gattii biofilm viability was measured by tetrazolium salt (XTT) assay (Martinez and Casadevall 2006). After biofilm formation and drug treatment, wells were washed with 100 µL of PBS and subsequently inoculated with a solution of 50 µL of 1 mg/ml XTT (Sigma-Aldrich) and 4 µL of 1 mM menadione (Sigma–Aldrich). After 1 h of incubation in the dark at 37°C, 50 µL of solution was transferred from each well to another plate and its absorbance was recorded at 490 nm.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The data obtained were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn´s. For all tests, the significance level adopted was P < 0.05.

Results

Susceptibility of C. gattii to SSRI drugs and synergistic effect with AmB

Fluoxetine hydrochloride (FLH) and PAH were active against C. gattii ATCC 56990 and C. gattii 5 with a MIC value of 31.25 µg/ml. Notably, the MFC for both drugs corresponded to the MIC. For C. gattii ATCC 56990, FLH + AmB combination resulted in two synergistic concentrations (FLH 3.9 µg/ml + AmB 0.125 µg/ml and FLH 7.8 µg/ml + AmB 0.125 µg/ml) with a 4-fold to 8-fold reduction in MIC values. Additionally, one synergistic combination for PAH + AmB (PAH 7.8 µg/ml + AmB 0.125 µg/ml) with a 4-fold reduction in MIC value was observed when combined with SSRI drugs (Table 1). For the C. gattii 5, an indifferent result to the combinations was observed.

Table 1.

Antifungal susceptibility assay and combinatory effect of SSRI and AmB against C. gattii.

| Susceptibility test (µg/mL) | Chequerboard assay | MIC reduction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | MIC | MFC | MICco µg/ml (SSRI + AmB) | FICI (effect) | SSRI drug | AmB |

| FLH | 31.25 | 31.25 | 3.9 + 0.125 | 0.3746 (Syn) | 8x | 4x |

| 7.8 + 0.125 | 0.4996 (Syn) | 4x | 4x | |||

| PAH | 31.25 | 31.25 | 7.8 + 0.125 | 0.4996 (Syn) | 4x | 4x |

| AmB | 0.5 | 0.5 | ||||

The checkerboard assay realized with C. neoformans ATCC 90112. MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; MFC, minimal fungicidal concentration; FICI, fractional inhibitory concentration index; syn, synergistic; MICco, MIC in the combination; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; AmB; Amphotericin B.

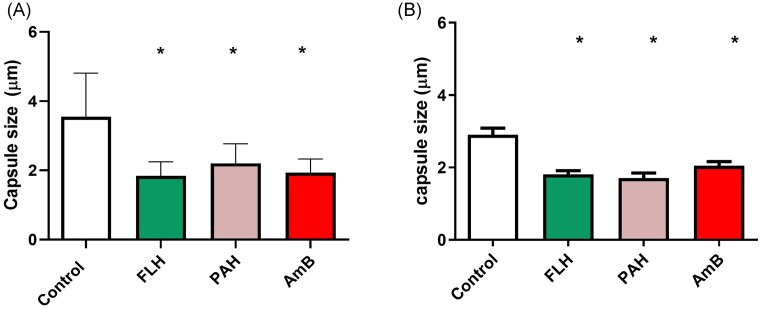

Effects of SSRI drugs on C. gattii capsule

The sub-MIC of FLH and PAH (15.62 µg/ml) significantly reduced C. gattii ATCC 56990 capsule size by 48.16% (P < 0.0001) and 38% (P < 0.0001), respectively. While AmB (0.25 µg/ml) reduced 45.52% (P < 0.0001) the capsule size. For C. gattii 5, FLH and PAH (15.62 µg/ml) reduced capsule size by 37.6% (P < 0.0001) and 41% (P < 0.0001), respectively. While the antifungal drug AmB (0.25 µg/ml) reduced 29.4% (P = 0.0003) the capsule size (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of SSRI treatment on capsule size of C. gattii at subinhibitory concentration. C. gattii ATCC 56990 (A). C. gattii 5 (B) FLH, fluoxetine hydrochloride; PAH, paroxetine hydrochloride; AmB, Amphotericin B. (*): represents statistical difference in relation to the control (p < 0.05).

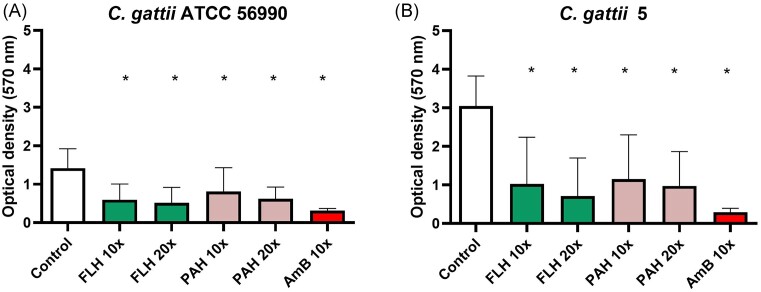

Effects of SSRI drugs on biofilm biomass

In the C. gattii ATCC 56990 biofilm, FLH treatment at 10x MIC and 20x MIC reduced biofilm biomass by 57.72% (P = 0.0002) and 63.44% (P < 0.0001), respectively. Paroxetine hydrochloride (PAH) at 10x MIC and 20x MIC decreased biofilm biomass by 42.69% (P = 0.0091) and 56.03% (P = 0.0009), respectively. Amphotericin B (AmB) at 10x MIC, used as a control, reduced biofilm biomass by 77.98% (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Effect of SSRI treatment on biofilm biomass of C. gattii. C. gattii ATCC 56990 (A). C. gattii 5 (B) FLH, fluoxetine hydrochloride; PAH, paroxetine hydrochloride; AmB, Amphotericin B. 10X, 10 folds the minimal inhibitory concentration; 20X, 20 folds the minimal inhibitory concentration. (*): represents statistical difference in relation to the control (p < 0.05).

For C. gattii 5, the treatment with FLH reduced biofilm biomass in 66.34% (P < 0.0001) at 10x MIC and in 76.66% (P < 0.0001) at 20x MIC (Fig. 3D). The treatment with PAH at 10x MIC and 20x MIC decreased biofilm biomass by 62.17% (P = 0.0005) and 68.03% (P = 0.0003) respectively. AmB at 10x MIC, used as a control, reduced 90.40% (P < 0.0001) of biofilm biomass (Fig. 2B).

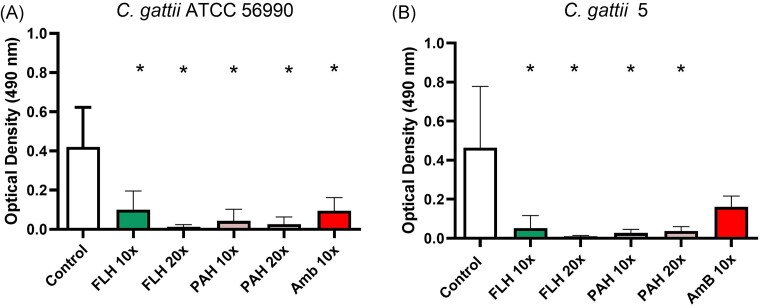

Figure 3.

Effect of SSRI treatment on the biofilm viability of C. gattii. C. gattii ATCC 56990 (A). C. gattii 5 (B) FLH, fluoxetine hydrochloride; PAH, paroxetine hydrochloride; AmB, Amphotericin B. 10X, 10 folds the minimal inhibitory concentration; 20X, 20 folds the minimal inhibitory concentration. (*): represents statistical difference in relation to the control (p < 0.05).

Effects of SSRI drugs on biofilm viability

The effect of the SSRI drugs on C. gattii biofilms was evaluated at 10x and 20x MIC and AmB at 10x MIC. For C. gattii ATCC 56990 the treatment with FLH revealed a decreased biofilm viability by 39.05% (P = 0.0109) and 78.94% (P = 0.0082) at 10x MIC and 20 × MIC, respectively. The biofilm viability percentage with treatment with PAH was 56.99% (P < 0.0001) and 67.64% (P < 0.0001) for 10x MIC and 20 × MIC, respectively. AmB 10x MIC used as a control, decreased biofilm viability by 42.24% (P = 0.0037) (Fig. 3A).

For C. gattii 5, the treatment with FLH revealed a decreased biofilm viability by 57.13% (P < 0.0001) and 84.62% (P < 0.0001) at 10x MIC and 20 × MIC, respectively. The biofilm viability percentage decreased for treatment with PAH was 65% (P < 0.0001) and 58.64% (P < 0.0001), for 10x MIC and 20× MIC, respectively. AmB 10x MIC, used as a control, decreased biofilm viability by 20.83% (P > 0.9999). All concentrations of both SSRI drugs exhibited statistically significant differences compared to the control group (Fig. 3B).

Discussion

Fungal infections have shown a significant increase in recent years, with cryptococcosis being notably prevalent among both immunocompromized and immunocompetent individuals (Perfect et al. 2010, Spitzer et al. 2017). Resistance to conventional treatments has been reported for Cryptococcus spp., coupled with the scarcity of antifungal options, elevated costs, and significant host toxicity, highlighting the imperative need for treatment alternatives (Rodero et al. 2003, Scorzoni et al. 2017).

Drug repositioning is a promising alternative to conventional antifungal treatment (Katragkou et al. 2016, Pushpakom et al. 2019) and drugs from the SSRI class have shown activity against fungal agents, including Candida spp, Aspergillus spp. and C. neoformans (Lass-Florl 2001, Oliveira et al. 2014, Pereira et al. 2021). However, there are no reports of SSRI drugs activities on C. gattii.

SSRI drugs have a proven inhibitory effect on Candida spp. by reducing biofilm formation and causing cell death by apoptosis. In addition, FLH was shown to inhibit fungal growth at concentrations of 127-508 µg/ml, and PAH at concentrations of 80–320 µg/ml (Costa Silva et al. 2017, Oliveira et al. 2018). For C.neoformans, the concentrations able to inhibit fungal growth were 9.6 µg/ml for FLH and 41 µg/mLlfor PAH (Pereira et al. 2021). In this study, both drugs, FLH and PAH showed a MIC of 31.25 µg/ml for C. gattii ATCC 56990 and C. gattii 5. When combined effects of SSRI drugs with AmB were evaluated, three synergistic combinations were found for C. gattii ATCC 56990, which reduced the MIC values by 4–8-fold.

Cryptococcus spp. capsule is a virulence mechanism essential for the pathogenicity of this yeast. It hinders phagocytosis and modulates host responses, contributing to disease progression. Understanding the capsule's molecular mechanisms is essential for developing effective cryptococcosis treatments (Zaragoza et al. 2008, Vecchiarelli et al. 2013). In this study, we demonstrated that subinhibitory concentration of FLH and PAH (15.62 µg/ml) reduced capsule size by up to 37.6%. In C. neoformans, at sub-MIC concentrations, FLH (4.8 µg/ml) and PAH (20 µg/ml) markedly decreased capsule size by up to 63% (Pereira et al. 2021).

Therefore, we evaluated the antibiofilm activity of the SSRI, FLH, and PAH on C. gattii. Our results indicate a significant reduction of biofilm biomass and viability by both drugs at 10x and 20x MIC. Studies with drugs from other classes, such as the anthelmintic benzimidazoles, have revealed a reduction in biofilms against C. neoformans, also proving active for C. gattii (Joffe et al. 2017).

The mechanisms action of the effect of SSRI on C. gattii is poorly described. Sertraline has been shown to affect intracellular membrane organization, translation, and vesicle transport (Zhai et al. 2012), given that both drugs are from SSRI, with a comparable mechanism of action, FLH and PAH could be acting similarly.

The treatment of systemic mycoses is considerably complicated by the limited number of antifungal drugs and the poor penetration of antifungals in the CNS due to the blood-brain barrier, only a few fungistatic drugs show reasonable penetration into the CNS. On the other hand, when the concentrations of SSRI drugs such as sertraline were analyzed in the cerebrospinal fluid and brain, they were ∼20–40 times higher compared to plasma levels (Lass-Florl 2001, Marchetti et al. 2004). Sertraline exhibited potent antifungal activity against C. neoformans, the main etiological agent of cryptococcal meningitis (Zhai et al. 2012). In addition, sertraline decreased the fungal burden in the brain and spleen of mice using murine model of cryptococcosis (Treviño-Rangel et al. 2016). Additionally, according to the British Pharmacopeia, lethal dose 50 (DL50) of SSRI drugs here evaluated are 374 mg/kg (PAH) and 452 mg/kg (FLH) when administrated orally in rats. Therefore, in vivo studies with SSRIs are needed to evaluate the efficiency of these drugs.

In summary, this study provides evidence of the potent anticryptococcal activity of FLH and PAH in vitro and its effects on C. gattii capsules and biofilm. However, future in vivo investigations to better describe these activities are required to demonstrate the relevance of FLH and PAH as antifungal agents for cryptococcosis.

Contributor Information

Letícia Rampazzo da Gama Viveiro, Department of Biosciences and Oral Diagnosis, Institute of Science and Technology, São Paulo State University (UNESP), São Paulo 12245-000, Brazil.

Amanda Rodrigues Rehem, Department of Biosciences and Oral Diagnosis, Institute of Science and Technology, São Paulo State University (UNESP), São Paulo 12245-000, Brazil.

Evelyn Luzia De Souza Santos, Department of Biosciences and Oral Diagnosis, Institute of Science and Technology, São Paulo State University (UNESP), São Paulo 12245-000, Brazil.

Paulo Henrique Fonseca do Carmo, Department of Biosciences and Oral Diagnosis, Institute of Science and Technology, São Paulo State University (UNESP), São Paulo 12245-000, Brazil.

Juliana Campos Junqueira, Department of Biosciences and Oral Diagnosis, Institute of Science and Technology, São Paulo State University (UNESP), São Paulo 12245-000, Brazil.

Liliana Scorzoni, Department of Biosciences and Oral Diagnosis, Institute of Science and Technology, São Paulo State University (UNESP), São Paulo 12245-000, Brazil; Programa de Pós-Graduação em Enfermagem, Universidade de Guarulhos, Guarulhos, São Paulo 07023-070, Brazil.

Author contributions

Letícia Rampazzo da Gama Viveiro (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft), Amanda Rodrigues Rehem (Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology), Evelyn Luzia De Souza Santos (Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology), Paulo Henrique Fonseca do Carmo (Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing), Junqueira J.C. (Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing), and Liliana Scorzoni (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing)

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arendrup MC, Meletiadis J, Mouton JW et al. Method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for yeasts. EUCAST DEFINITIVE DOCUMENT E.DEF 7.3.1. 2017:1–21.

- Costa Silva RA, da Silva CR, de Andrade Neto JB et al. In vitro anti-Candida activity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors against fluconazole-resistant strains and their activity against biofilm-forming isolates. Microb Pathog. 2017;107:341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz AFP, Melho VM, De Souza BFX et al. Antidepressant drugs: prevalence, profile and knowledge of the user population. Braz J Health Pharm. 2020;2:28–34. 10.29327/226760.2.2-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gow NAR, Johnson C, Berman J et al. The importance of antimicrobial resistance in medical mycology. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe LS, Schneider R, Lopes W et al. The anti-helminthic compound mebendazole has multiple antifungal effects against cryptococcus neoformans. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katragkou A, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. Can repurposing of existing drugs provide more effective therapies for invasive fungal infections?. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17:1179–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass-Florl C. Antifungal properties of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors against Aspergillus species in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:775–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti E, Chaillan FA, Dumuis A et al. Modulation of memory processes and cellular excitability in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats by a 5-HT4 receptors partial agonist, and an antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:1021–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez LR, Casadevall A. Susceptibility of cryptococcus neoformans biofilms to antifungal agents In vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1021–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SE, Capitão LP, Giles SLC et al. The knowns and unknowns of SSRI treatment in young people with depression and anxiety: efficacy, predictors, and mechanisms of action. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:824–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odds FC. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AS, Gaspar CA, Palmeira-de-Oliveira R et al. Anti-Candida activity of fluoxetine alone and combined with fluconazole: a synergistic action against fluconazole-resistant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4224–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AS, Martinez-de-Oliveira J, Donders GGG et al. Anti-Candida activity of antidepressants sertraline and fluoxetine: effect upon pre-formed biofilms. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl). 2018;207:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters E, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Comparison of multiple methods for quantification of microbial biofilms grown in microtiter plates. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;72:157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira TC, de Menezes RT, de Oliveira HC et al. In vitro synergistic effects of fluoxetine and paroxetine in combination with amphotericin B against Cryptococcus neoformans. Pathog Dis. 2021;79:1–9. 10.1093/femspd/ftab001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushpakom S, Iorio F, Eyers PA et al. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodero L, Mellado E, Rodriguez AC et al. G484S Amino acid substitution in lanosterol 14-α demethylase (ERG11) is related to fluconazole resistance in a recurrent cryptococcus neoformans clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3653–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues ML, Nosanchuk JD. Fungal diseases as neglected pathogens: a wake-up call to public health officials. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0007964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueden CT, Hiner MC, Eliceiri KW. ImageJ: image analysis interoperability for the next generation of biological image data. Microsc Microanal. 2016;22:2066–7. [Google Scholar]

- Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA et al. Practice Guidelines for the management of Cryptococcal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:710–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorzoni L, de Paula e Silva ACA, Marcos CM et al. Antifungal therapy: new advances in the understanding and treatment of mycosis. Front Microbiol. 2017;08:1–23. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer M, Robbins N, Wright GD. Combinatorial strategies for combating invasive fungal infections. Virulence. 2017;8:169–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer DJ, Chaturvedi V. Projecting global occurrence of cryptococcus gattii. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treviño-Rangel R de J, Villanueva-Lozano H, Hernández-Rodríguez P et al. Activity of sertraline against Cryptococcus neoformans: in vitro and in vivo assays. Med Mycol. 2016;54:280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchiarelli A, Pericolini E, Gabrielli E et al. Elucidating the immunological function of the Cryptococcus neoformans capsule. Future Microbiol. 2013;8:1107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza O, Casadevall A. Experimental modulation of capsule size in Cryptococcus neoformans. Biol Proced Online. 2004;6:10–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza O, Chrisman CJ, Castelli MV et al. Capsule enlargement in Cryptococcus neoformans confers resistance to oxidative stress suggesting a mechanism for intracellular survival. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2043–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai B, Wu C, Wang L et al. The antidepressant sertraline provides a promising therapeutic option for neurotropic cryptococcal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3758–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]