Abstract

Legionella pneumophila, a gram-negative bacterium causing Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever, was shown to be highly reactive in in vitro gelation of Limulus lysate but not able to induce fever and the local Shwartzman reaction in rabbits and mice. We analyzed the capacity of purified L. pneumophila lipopolysaccharide (LPS-Lp) to induce activation of the human monocytic cell line Mono Mac 6, as revealed by secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and desensitization to subsequent LPS stimulation. We showed that despite normal reactivity of LPS-Lp in the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay, induction of cytokine secretion in Mono Mac 6 cells and desensitization to an endotoxin challenge required LPS-Lp concentrations 1,000 times higher than for LPS of Salmonella enterica serovar Minnesota. Therefore, we examined the interaction of LPS-Lp with the LPS receptor CD14. We demonstrated that LPS-Lp did not bind to membrane-bound CD14 expressed on transfected CHO cells, nor did it react with soluble CD14. Our results suggest that the low endotoxic potential of LPS-Lp is due to a failure of interaction with the LPS receptor CD14.

Soon after the discovery of Legionella pneumophila as the causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever, it was shown that this gram-negative bacterium was highly reactive in in vitro gelation of Limulus lysate (5–8, 42). The same suspension of cells, however, was not able to induce fever and local Shwartzman reaction in rabbits and mice (33, 42, 43). In rabbits, the toxicity of L. pneumophila was less than 3% of that of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and less than 0.08% of that of a Salmonella enterica serovar Minnesota endotoxin preparation (42). Chemical analysis revealed an unique structure of the L. pneumophila lipopolysaccharide (LPS-Lp): the O chain of this LPS (Lp-O chain) constitutes a homopolymer of an unusual sugar, 5-acetamidino-7-acetamido-8-O-acetyl-3,5,7,9-tet- radeoxy-l-glycero-d-galacto-nonulosonic acid (legionaminic acid), which renders the cell surface highly hydrophobic and thus may support adherence to the membrane of amoebae in the natural environment and to the membrane of alveolar macrophages in the human lung (46). An epitope located in the vicinity of the 8-O-acetyl group of legionaminic acid is assumed to be associated with L. pneumophila virulence (13). The outer core oligosaccharide also exhibits hydrophobic properties due to the presence of N- and O-acetyl groups as well as 6-deoxy sugars. The inner core is comparable to enterobacterial core oligosaccharides in containing 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acids but lacks heptose and phosphate. Lipid A consists of unusual long, branched-chain fatty acids that could be responsible for the observed low endotoxicity in animals and may protect intracellular bacteria from digestion by esterases present in amoebae as the natural host in the aquatic environment (46). Similar complex and unusual compositions were found in L. israelensis, L. maceachernii, and L. micdadei (36), L. oakridgensis and L. erythra (37), L. bozemanii and L. longbeachae (38), and in L. feeleii, L. hackeliae, and L. jordanis (39) and thus constitute a characteristic feature of Legionella lipid A. Based on these structural features, we hypothesized that the lipid A of L. pneumophila (Lp-lipid A) may differ in structure from enterobacterial lipid A in the degree of macrophage activation. We therefore analyzed the capacity of LPS-Lp to induce activation of the human monocytic cell line Mono Mac 6 as revealed by secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and desensitization to subsequent LPS stimulation. Furthermore, the interaction of LPS-Lp with the putative LPS receptor CD14 was investigated to further prove or disprove a structure-function relationship in LPS-Lp and Lp-lipid A with respect to biological activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

LPS.

LPS from S. enterica serovar Minnesota (LPS-Sm) and LPS from Escherichia coli O55:B5 (LPS-Ec) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (Munich, Germany). LPS and [3H]LPS from E. coli LCD 25 were purchased from List Biological Laboratories (Campbell, Calif.). Lipid A from E. coli F515 was a kind gift from H. Brade (Forschungsinstitut Borstel, Borstel, Germany). LPS-Lp, from L. pneumophila serogroup 1 (Philadelphia 1), was extracted as described by Moll et al. (26). Lp-Lipid A and Lp-O chain were isolated from the Lp-LPS as described by Knirel et al. (21).

Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay.

Endotoxic potencies of LPS-Lp and LPS-Sm were compared by using a chromogenic Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay kit (Coatest; Chromogenix, Charleston, S.C.); 1,000, 500, 200, and 100 pg each of LPS-Sm and LPS-Lp per ml were quantified. The samples were diluted and analyzed as instructed by the manufacturer, using a Milenia ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) reader (DPC Biermann, Bad Nauheim, Germany). Results were documented as means of three experiments ± standard deviation (SD).

Culture of Mono Mac 6 cells.

Mono Mac 6 cells were kindly donated by H. W. L. Ziegler-Heitbrock (Institute of Immunology, University of Munich) and were cultured as replicative nonadherent monocytes under LPS-free conditions in 250-ml flasks (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in 50 ml of RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany) supplemented with 10% selected fetal calf serum (Myoclone Plus; Gibco), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 1 mM pyruvic acid (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), 1% nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 9 μg of insulin (Sigma) per ml, and 1 mM oxalacetate (Sigma) (Mono Mac 6 medium) at 35°C in 5% CO2 as described by Ziegler-Heitbrock et al. (47) and were diluted 1:3 twice a week in fresh medium.

Stimulation of Mono Mac 6 cells.

Mono Mac 6 cells (2 × 106 per ml) were transferred to a well of a 24-well tissue culture plate (Nunc). For stimulation, LPS-Lp was added to final concentrations of 1, 10, 100, 1,000, and 10,000 ng/ml in serum-free Mono Mac 6 medium and in Mono Mac 6 medium supplemented with 5% fresh human AB serum as a source of LPS-binding protein (LBP). Production of proinflammatory cytokines was determined in the cell culture supernatant 0, 4, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after addition of LPS. Basal production of proinflammatory cytokines by Mono Mac 6 cells, cytokine secretion after stimulation with 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1,000 ng of LPS-Sm per ml, and cytokine production in the presence of polymyxin B (10 and 100 μg/ml) were determined as a control. All experiments were repeated at least five times.

Determination of cytokine production.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), soluble interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6 (all from Quantikine, Minneapolis, Minn.), and IL-8 (Interleukin-8 Milenia; DPC Biermann) were determined by ELISA as instructed by the manufacturer. All samples were measured as duplicate. Results were expressed as picograms per milliliter and were documented as means of five experiments ± SD.

Desensitization of Mono Mac 6 cells.

Mono Mac 6 cells were preincubated for 18 h at 37°C with LPS-Sm and LPS-Lp, using concentrations of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 μg of LPS per ml (2 × 106 Mono Mac 6 cells per ml). After 18 h, the cells were washed three times and exposed to 10 μg of LPS-Ec per ml for 72 h. Production of proinflammatory cytokines produced after challenge with LPS-Ec by Mono Mac 6 cells or by desensitized Mono Mac 6 cells was expressed as picograms per milliliter and documented as means ± SD from four experiments.

Binding of LPS to CHO cells transfected with human CD14 cDNA.

CHO cells transfected with human CD14 cDNA were cultured as previously described (40). We analyzed whether LPS-Lp or its partial structures compete with [3H]LPS-Ec for binding to membrane-bound CD14 expressed on these cells. Briefly, CHO cells were trypsinized, washed in ice-cold HNE buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), and preincubated for 30 min at 37°C in SEBDAF buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 300 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 10 mM NaN3, 2 mM NaF, 5 mM deoxyglucose). The cells were then centrifuged, resuspended in SEBDAF buffer, and counted. [3H]LPS-Ec (specific activity, 2.09 × 106 dpm/μg; final concentration, 40 ng/ml) was sonicated for 10 min and mixed with 2 × 105 cells in a final volume of 50 μl in the presence or absence of histidine-tagged mouse LBP (final concentration, 1.4 μg/ml), kindly provided by Xiaolong Fan (Institute of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Greifswald, Germany) (9). Binding was competed with different amounts of unlabeled LPS or LPS partial structures as indicated. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min with frequent shaking, and the reaction was terminated by addition of 450 μl of ice-cold HNE buffer and centrifugation at 2,800 × g for 30 s. The cells were washed with 500 μl of ice-cold HNE buffer and then resuspended in 100 μl of HNE buffer. Cell-associated 3H was counted after addition of 200 μl of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10 mM EDTA and 3 ml of scintillation fluid (18, 20, 41). Results are expressed as means ± SD of triplicate experiments.

Binding of LPS to sCD14.

Human recombinant soluble CD14 (sCD14) was purified by affinity chromatography from pooled serum-free supernatants of transfected CHO cells. Briefly, the anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody biG-2 (Biometec GmbH, Greifswald, Germany) (35) was coupled to a HiTrap N-hydroxy-succinimide-activated Sepharose column (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). After passage of the supernatant, the column was washed with 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and sCD14 was eluted with 0.1 M glycine buffer (pH 3.0). The pH was immediately adjusted to 8.0 by addition of 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The material was then concentrated by ultrafiltration in a Centricon 30 concentrator (Amicon Inc., Beverly, Mass.) and equilibrated with PBS. To test binding of LPS to sCD14, sCD14 (50 μg/ml) was mixed with LPS (80 μg/ml) and incubated overnight at 37°C in a final volume of 10 μl of PBS. In the presence of LBP (final concentration, 1.4 μg/ml), incubation time was reduced to 30 min. Reaction mixes were loaded onto 4 to 15% Tris-glycine gels, pH 8.8 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany), and separated by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). sCD14 was detected by Western blotting as previously described (40).

RESULTS

Reactivity of LPS in the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay.

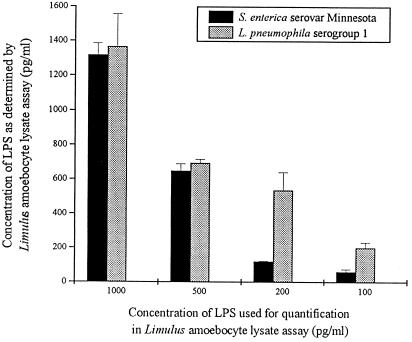

Reactivities of LPS-Sm and LPS-Lp in the Coatest were nearly identical with higher concentrations (500 and 1,000 pg), whereas with lower concentrations, LPS-Lp was more potent than LPS-Sm (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Reactivities of LPS-Lp and LPS-sm in the Limulus amoebocyte lysate test. Data are means ± SD of three experiments.

Production of proinflammatory cytokines after stimulation with LPS-Lp.

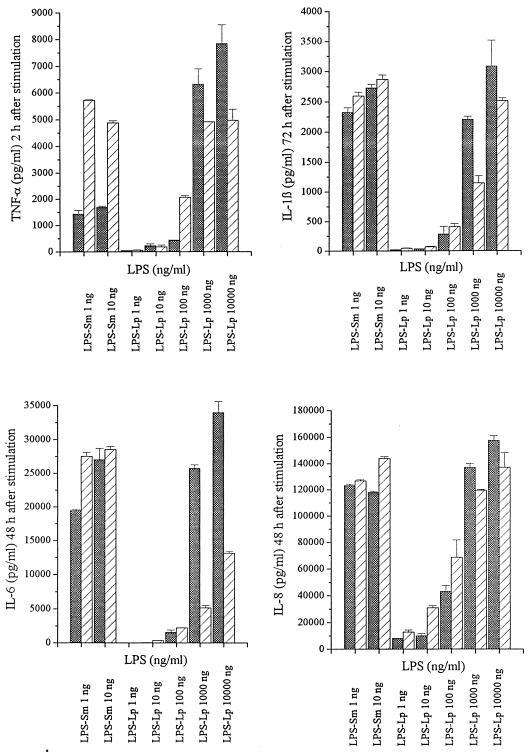

To compare the stimulatory capacity of LPS-Sm with that of LPS-Lp, the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 by Mono Mac 6 cells was determined after stimulation with the endotoxins in the presence or absence of human AB serum. Unstimulated Mono Mac 6 cells did not produce detectable amounts of proinflammatory cytokines. After stimulation with LPS-Lp as well as with LPS-Sm, production of proinflammatory cytokines by Mono Mac 6 cells showed a cytokine response with time kinetics characteristic for the cytokine: maximal TNF-α production was detected 2 h after stimulation, IL-6 and IL-8 were secreted at maximum levels 48 h after stimulation, and maximal soluble IL-1β levels appeared 72 h after stimulation in the supernatant (data not shown). Dependence of cytokine production on LPS concentration is shown in Fig. 2; with LPS-Sm, significant cytokine production by Mono Mac 6 cells was observed after stimulation with 1 ng/ml. Fast ongoing production of TNF-α was further increased in the presence of human AB serum. With LPS-Lp, minimal amounts of cytokines could be detected in the supernatant after stimulation with 100 ng/ml. Cytokine levels comparable to those obtained with 1 ng of LPS-Sm per ml were observed with 1,000 ng of LPS-Lp per ml, indicating that LPS-Sm has a cytokine-inducing capacity 1,000-fold higher than that of LPS-Lp. Addition of serum caused a decrease of cytokine production if stimulation was performed with 1,000 and 10,000 ng of LPS-Lp per ml. Addition of polymyxin B, a potent inhibitor of endotoxin activity, resulted in complete inhibition of cytokine secretion after stimulation with LPS-Sm at all concentrations tested, whereas cytokine production after stimulation with LPS-Lp was not blocked (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by Mono Mac 6 cells after stimulation with various concentrations of LPS-Sm and LPS-Lp, with (▨) and without (▩) addition of human AB serum. Data are means ± SD of five experiments.

FIG. 3.

Inactivation of LPS-Sm and LPS-Lp by polymxin B (PmB). Data are means ± SD of five experiments.

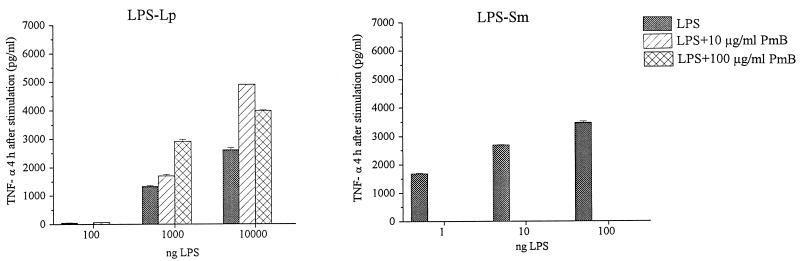

Desensitization of Mono Mac 6 cells for endotoxin-induced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines.

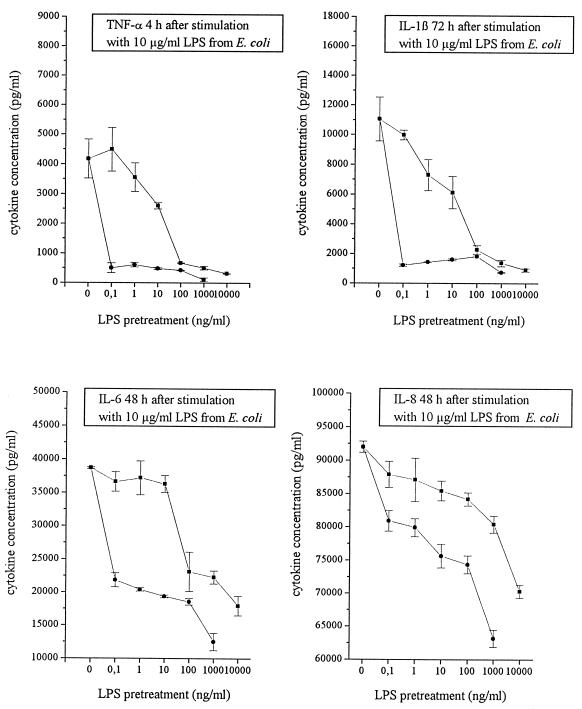

Mono Mac 6 cells were preincubated with various concentrations of LPS-Sm or LPS-Lp. After 24 h, the cells were exposed to 10 μg of LPS-Ec per ml. Concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines in the supernatant were determined at the time points of maximal secretion. Whereas 0.1 ng of LPS-Sm per ml was sufficient to induce a pronounced endotoxin tolerance in Mono Mac 6 cells, about 100 ng of LPS-Lp per ml was necessary to induce the same degree of inhibition of cytokine secretion (Fig. 4). Again, LPS-Sm was 1,000-fold more potent than LPS-Lp in desensitization of Mono Mac 6 cells.

FIG. 4.

Desensitization of Mono Mac 6 cells for proinflammatory cytokine production in response to a subsequent challenge with LPS-Ec after preincubation with LPS-Sm (•) in comparison to preincubation with LPS-Lp (■). Data are means ± SD of four experiments.

Interaction of LPS-Lp with the LPS receptor CD14.

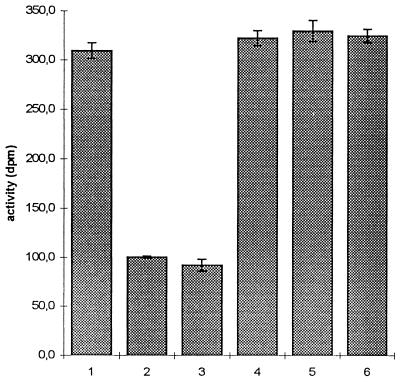

To determine whether the low endotoxic potential of LPS-Lp was caused by a failure of interaction with the monocyte LPS receptor, we analyzed binding of LPS-Lp to membrane-bound and soluble CD14. In the experiment shown in Fig. 5, CHO cells expressing the human CD14 molecule were incubated with 40 ng of [3H]LPS-Ec per ml in the presence or absence of a 1,000-fold excess of competitors. The amount of [3H]LPS-Ec bound in the absence of LBP was considered non-CD14 dependent (negative control). Whereas addition of unlabeled LPS-Ec reduced the binding of tritiated LPS to the control level, addition of LPS-Lp, Lp-lipid A, or purified Lp-O chain did not block the binding of [3H]LPS-Ec to the cells.

FIG. 5.

Competition of LPS-Lp with [3H]LPS-Ec for binding to CD14+ CHO cells. Cells were incubated with [3H]LPS-Ec in the presence (bars 1 and 3 to 6) or absence (bar 2) of LBP as described in Materials and Methods, and cell-bound activity was counted by liquid scintillation counting. Bars 1 and 2, no competitor; bars 3 to 6, 1,000-fold excess of unlabeled LPS-Ec LCD 25, LPS-Lp, Lp-lipid A, and Lp-O chain, respectively. Data are means ± SD of three experiments.

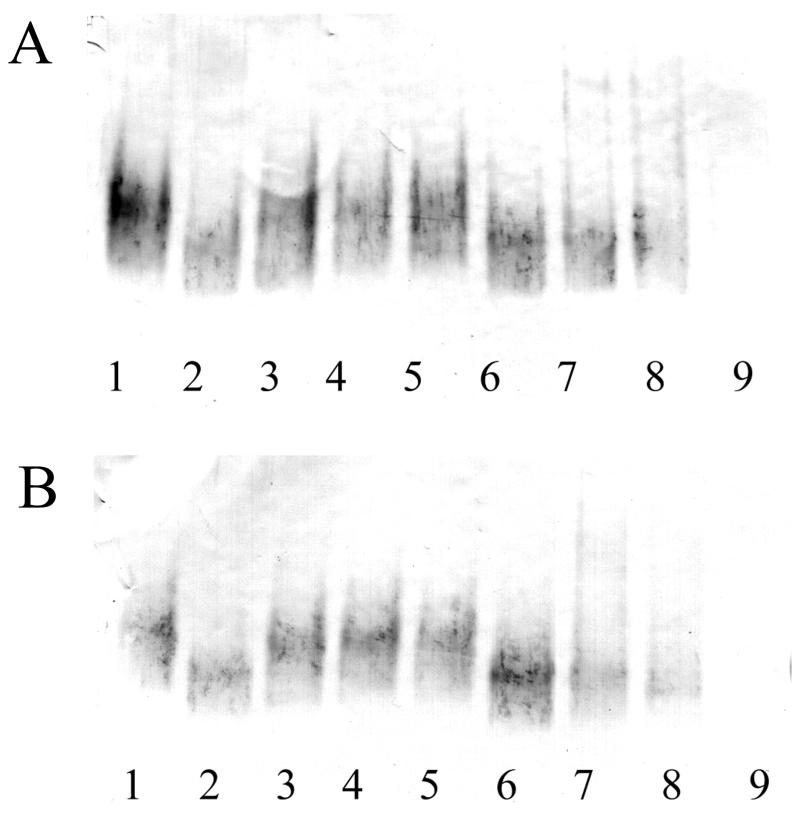

To test the binding of LPS-Lp to CD14 directly, a native PAGE assay was performed (Fig. 6). Incubation of recombinant sCD14 with LPS-Ec, LPS-Sm, and E. coli lipid A caused a mobility shift, indicating that stable complexes between sCD14 and these molecules were formed. However, there was no shift of the sCD14 band after incubation with LPS-Lp, Lp-lipid A, or Lp-O chain (Fig. 6A). Identical results were obtained in the presence of LBP (Fig. 6B). These results show that there is no interaction between CD14 and LPS-Lp or LPS-Lp-derived partial structures and that the presence of LBP cannot mediate binding of LPS-Lp to CD14.

FIG. 6.

Native PAGE assay. sCD14 (50 μg/ml) (lane 1) was incubated with LPS-Ec LCD 25 (lane 2), LPS-Lp (lane 3), Lp-O chain (lane 4), Lp-lipid A (lane 5), lipid A of LPS-Ec (lane 6), LPS-Ec O55:B5 (lane 7), and LPS-Sm (lane 8) (each at 80 μg/ml) in a volume of 10 μl. Reactions were run on a 4 to 15% native polyacrylamide gel. sCD14 was detected by Western blotting using a rabbit anti-CD14 antiserum. Lane 9, mixture of all LPSs without CD14. Incubation was performed in the absence (A) or presence (B) of mouse recombinant LBP.

DISCUSSION

Reduced endotoxic potency accompanied by full activity in the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (Fig. 1) has been described for the LPSs of gram-negative facultative intracellular bacteria such as Rickettsia (32), Brucella abortus (28), Bordetella pertussis (2), Chlamydia trachomatis (16), and Francisella tularensis (1). Investigations of structure-activity relationships revealed that the number, distribution, and chain length of acyl groups are essential for the expression of endotoxicity (30, 31). The fatty acid chains of LPS-Lp are twice as long as those of the highly endotoxic enterobacterial LPS (30, 46). Therefore, the low endotoxicity and pyrogenicity of the LPS from L. pneumophila described in an early report by Wong et al. (42) likely reflected the unique structure of the lipid A moiety. We used the well-established Mono Mac 6 cell culture model to correlate the reported low endotoxic potential of LPS-Lp in animals with the level of proinflammatory cytokines produced by this monocytic cell line after stimulation with enterobacterial LPS. For that purpose, we compared the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 induced by LPS-Lp with the cytokine production induced by LPS-Sm. As shown, activation of Mono Mac 6 cells to produce proinflammatory cytokines required concentrations of LPS-Lp about 1,000-fold higher than for enterobacterial LPS (Fig. 2). Addition of human AB serum as a source of LBP was able to influence the cytokine production. Short-time cellular activation by LPS-Sm, i.e., TNF-α production within 2 h, was enhanced by the addition of serum (Fig. 2) due to the presence of LBP as a catalyst of LPS binding to membrane-bound CD14. In contrast, activation of Mono Mac 6 cells by equally potent, i.e., 1000-fold-higher, concentrations of LPS-Lp could be in part inhibited by human AB serum. It is well established that high LPS concentrations such as those used in case of LPS-Lp are not dependent on supportive LBP effects (3, 24, 19), but it remains to be examined which serum proteins other than selective LBP are able to mediate LPS-Lp enhancing or inhibiting effects. Many serum proteins which are known to bind to LPS (i.e., high-density lipoprotein, bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein, serum albumin, lysozyme, and complement component C1q) may be candidates for interaction with LPS-Lp, (34, 44), but it was not the aim of this investigation to characterize such possible binding proteins.

We could also demonstrate a distinct difference in neutralization by polymyxin B between LPS-Lp and LPS-Sm: addition of polymxin B abolished the cytokine production induced by LPS-Sm but did not suppress the cytokine production induced by LPS-Lp (Fig. 3). This result correlates well with the previous observation that preincubation of L. pneumophila cells with polymyxin B before injecting them into mice did not significantly reduce their toxicity, whereas the toxicity of N. gonorrhoeae and Salmonella LPS was reduced about four- to fivefold (42). LPS-Lp has characteristic structural features such as lack of negatively charged groups (phosphate and phosphatidylethanolamine) and the presence of a hydrophobic outer core structure (three deoxy sugars and four O-acetyl groups) (22, 27, 45). This lack of charges, together with the hydrophobic Lp-O chain, likely prevents the proper intercalation of polymyxin B to the outer membrane of L. pneumophila. Therefore, this result is in agreement with earlier observations that neutralization of an LPS by polymyxin B is dependent on the charge, hydrophobicity, and acylation pattern of that LPS (12, 29).

Induction of LPS tolerance in monocytes and macrophages by preincubation with low doses of conventional LPS is a well-known phenomenon (10, 11, 48). The downregulation of cytokine production in tolerized cells occurs at the pretranslational level (49). LPS-Lp was 1,000-fold less active than LPS-Sm in desensitizing Mono Mac 6 cells for endotoxin-induced cytokine secretion (Fig. 4).

In this study, we showed that despite the normal reactivity of LPS-Lp in the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay, cellular activation of Mono Mac 6 cells and desensitization to an endotoxin challenge required LPS-Lp concentrations about 1,000-fold higher than for enterobacterial LPS. Either of two possible mechanisms may cause this difference: (i) lack of binding of LPS-Lp to the LPS receptor CD14 or (ii) lack of induction of receptor-mediated signalling. To answer this question, we investigated the interaction of LPS-Lp with the LPS receptor CD14. Our results demonstrate that neither LPS-Lp, Lp-lipid A, nor purified Lp-O chain is able to interact with the monocytic LPS receptor CD14 (Fig. 5 and 6). We therefore conclude that the low endotoxic potential of LPS-Lp is caused by the failure of interaction of LPS-Lp or LPS-Lp-derived partial structures with CD14.

Failure of interaction with LPS receptors of bone marrow cells of C3H/HeOu mice was recently described with respect to the LPS of another intracellular bacterial pathogen, F. tularensis (1). The LPSs of other bacterial species exhibiting low endotoxic capacity, such as Helicobacter pylori or Porphyromonas gingivalis, display lower transfer rates to CD14 due to poor binding to LBP (4). In this study, we clearly showed that LPS-Lp cannot bind to sCD14 (Fig. 6) or interact with the monocytic LPS receptor CD14 (Fig. 5) and therefore exhibited a 1,000-fold-reduced capacity to activate monocytes to produce proinflammatory cytokines or to desensitize macrophages to a subsequent LPS challenge. It remains to be determined whether LPS-Lp is able to interact with LPS receptors other than CD14 (17) or to undergo a receptor-independent intercalation into the phospholipid cell membrane as was suggested for high concentrations of enterobacterial LPS (23, 34).

If the endotoxic capacity of LPS-Lp is so dramatically reduced, this LPS may have developed other functions during evolution. The hydrophobic character of LPS-Lp may support the concentration of legionellae in aerosols, a means by which these pathogens can reach the alveolar macrophages. It may furthermore contribute to adherence to the host cells and help protect against enzymatic destruction within these cells. All of these mechanisms may lead to the distribution of the bacteria by amoebae as their natural host in the environment as well as to initiation of pulmonary infection in humans (46). LPS-Lp is able to induce the classical pathway of complement activation (25) and thus enhance the uptake of L. pneumophila by mononuclear phagocytes (15).

Although such speculation is not confirmed by experimental investigations, the long-chain fatty acids of LPS-Lp may interfere with the phospholipid bilayer of the phagosome membrane and thus block the fusion of phagosome and lysosome as was observed for L. pneumophila (14).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ancuta P, Pedron T, Girard R, Sandström G, Chaby R. Inability of the Francisella tularensislipopolysaccharide to mimic or to antagonize the induction of cell activation by endotoxins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2041–2046. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2041-2046.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondiau C, Lagadec P, Lejeune P, Onier N, Cavaillon J M, Jeannin J F. Correlation between the capacity to activate macrophages in vitro and the antitumor activity in vivo of lipopolysaccharides from different bacterial species. Immunobiology. 1994;190:243–254. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80272-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corrales I, Weersink A J L, Verhoef J, Van Kessel K P M. Serum-independent binding of lipopolysaccharide to human monocytes is trypsin sensitive and does not involve CD14. Immunology. 1993;80:84–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham M D, Seachord C, Ratcliffe K, Bainbridge B, Aruffo A, Darveau R P. Helicobacter pylori and Porphyromonas gingivalislipopolysaccharides are poorly transferred to recombinant soluble CD14. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3601–3608. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3601-3608.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fumarola D. Attempts to biological demonstration of endotoxin potency in Legionella pneumophila. Ann Sclavo. 1979;21:258–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fumarola D. Endotoxic potency of the Legionella pneumophila: recent data. Boll Ist Sieroter Milan. 1979;58:100–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fumarola D. Legionella pneumophilaand limulus endotoxin assay: recent findings. Infection. 1979;7:198–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01640945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fumarola D. Recent advances in the structure, biochemical and biological aspects of the “Legionella pneumophila”, the causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease: a review. Ann Sclavo. 1979;21:63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grunwald U, Fan X, Jack R S, Workalemahu G, Kallies A, Stelter F, Schütt C. Monocytes can phagocytose Gram-negative bacteria by a CD14-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 1996;157:4119–4125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas J G, Thiel C, Blömer K, Weiss E H, Riethmüller G, Ziegler-Heitbrock H W L. Downregulation of tumor necrosis factor expression in the human Mono Mac 6 cell line by lipopolysaccharide. J Leukocyte Biol. 1989;46:11–14. doi: 10.1002/jlb.46.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas J G, Baeuerle P A, Riethmüller G, Ziegler-Heitbrock H W L. Molecular mechanisms in down-regulation of tumor necrosis factor expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9563–9567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helander I M, Kilpelainen I, Vaara M. Increased substitution of phosphate groups in lipopolysaccharides and lipid A of the polymyxin-resistant pmrA mutants of Salmonella typhimurium: a 31P-NMR study. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:481–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helbig J H, Lück P C, Knirel Y A, Witzleb W, Zähringer U. Molecular characterization of a virulence-associated epitope on the lipopolysaccharide of Legionella pneumophilaserogroup 1. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:71–78. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horwitz M A. The Legionnaires’ disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1983;158:2108–2126. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horwitz M A. Phagocytosis of the Legionnaires’ disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) occurs by a novel mechanism: engulfment within a pseudopod coil. Cell. 1984;36:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingalls R R, Rice P A, Qureshi N, Takayama K, Lin J S, Golenbock D T. The inflammatory cytokine response to Chlamydia trachomatisinfection is endotoxin mediated. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3125–3130. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3125-3130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kielian T L, Blecha F. CD14 and other recognition molecules for lipopolysaccharide: a review. Immunopharmacology. 1995;29:187–205. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00003-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkland T N, Finley F, Leturcq D, Moriarty A, Lee J D, Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S. Analysis of lipopolysaccharide binding by CD14. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24818–24823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitchens R L, Ulevitch R J, Munford R S. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) partial structures inhibit responses to LPS in a human macrophage cell line without inhibiting LPS uptake by a CD14-mediated pathway. J Exp Med. 1992;176:485–494. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitchens R L, Munford R S. Enzymatically deacylated lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can antagonize LPS at multiple sites in the LPS recognition pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9904–9910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knirel Y A, Rietschel E T, Marre R, Zähringer U. The structure of the O specific chain of Legionella pneumophilaserogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Eur J Biochem. 1994;221:239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knirel Y A, Moll H, Zähringer U. Structural study of a highly O-acetylated core of Legionella pneumophilaserogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr Res. 1996;293:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(96)00194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luchi M, Munford R S. Binding, internalization, and deacylation of bacterial lipopolysaccharide by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1993;151:959–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynn W A, Kiu Y, Golenbrock D T. Neither CD14 nor serum is absolutely necessary for activation of mononuclear phagocytes by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4452–4461. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4452-4461.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mintz C S, Schultz D R, Arnold P I, Johnson W. Legionella pneumophilalipopolysaccharide activates the classical complement pathway. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2769–2776. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2769-2776.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moll H, Sonesson A, Jantzen E, Marre R, Zahringer U. Identification of 27 oxo octacosanoic acid and heptacosane 1,27 dioic acid in Legionella pneumophila. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;76:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90354-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moll H, Knirel Y A, Helbig J H, Zähringer U. Identification of an α-d-Manp-(1→8)-Kdo disaccharide in the inner core region and the structure of the complete core region of the Legionella pneumophilaserogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr Res. 1997;304:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)00210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munoz J J, Bergman R K, Robbins K E. Comparison of the histamine hypersensitivity and the Limulusamoebocyte lysate tests for endotoxin activity. Infect Immun. 1978;22:292–294. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.1.292-294.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nummila K, Kilpelainen I, Zähringer U, Vaara M, Helander I M. Lipopolysaccharides of polymyxin B-resistant mutants of Escherichia coliare extensively substituted by 2-aminoethyl pyrophosphate and contain aminoarabinose in lipid A. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rietschel E T, Brade H. Bacterial endotoxins. Sci Am. 1992;267:54–61. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0892-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rietschel E T, Kirikae T, Schade F U, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer A J, Zähringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F, Schreier M, Brade H. Bacterial endotoxin: molecular relationships of structure to activity and function. FASEB J. 1994;8:217–225. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schramek S, Brezina R, Kazar J. Some biological properties of an endotoxic lipopolysaccharide from the typhus group Rickettsiae. Acta Virol. 1977;21:439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schramek S, Kazar J, Bazovska S. Lipid A in Legionella pneumophila. Zbl Bakteriol Hyg Abt I Orig Reihe A. 1982;252:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schromm A B, Brandenburger K, Rietschel E T, Flad H D, Carroll S F, Seydel U. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein mediates CD14-independent intercalation of lipopolysaccharide into phospholipid membranes. FEBS Lett. 1996;399:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schütt C, Witt S, Grunwald U, Stelter F, Schilling T, Fan X, Marquart B P, Bassarab S, Krüger C. Epitope mapping of CD14 glycoprotein. In: Schlossmann S F, editor. Leucocyte typing V. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 785–788. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonesson A, Jantzen E, Bryn K, Tangen T, Eng J, Zähringer U. Composition of 2,3-dihydroxy fatty acid-containing lipopolysaccharides from Legionella israelensis, Legionella maceachernii and Legionella micdadei. Microbiology. 1994;140:1261–1271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-6-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonesson A, Jantzen E, Tangen T, Zähringer U. Lipopolysaccharides of Legionella erythra and Legionella oakridgensis. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:666–671. doi: 10.1139/m94-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonesson A, Jantzen E, Tangen T, Zähringer U. Chemical composition of lipopolysaccharides from Legionella bozemanii and Legionella longbeachae. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:215–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00301841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sonesson A, Jantzen E, Tangen T, Zähringer U. Chemical characterization of lipopolysaccharides from Legionella feeleii, Legionella hackeliae and Legionella jordanis. Microbiology. 1994;140:2663–2671. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stelter F, Pfister M, Bernheiden M, Jack R S, Bufler P, Engelmann H, Schütt C. The myeloid differentiation antigen CD14 is N- and O-glycosylated: contribution of N-linked glycosylation to different soluble CD14 isoforms. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:457–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stelter F, Bernheiden M, Jack R S, Witt S, Pfister M, Schütt C. Mutation of amino acids 39-44 of human CD14 abrogates binding of lipopolysaccharide and Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1997;143:100–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong K H, Moss C W, Hochstein D H, Arko R J, Schalla W P. Endotoxicity of the Legionnaires’ disease bacterium. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:624–627. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-4-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong K H, Feeley J C. Lipopolysaccharide of Legionellaas adjuvant for intrinsic and extrinsic antigens. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1984;177:475–481. doi: 10.3181/00379727-177-41975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wurfel M M, Kunitake S T, Lichenstein H, Kane J P, Wright S D. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein is carried on lipoproteins and act as cofactor in the neutralization of LPS. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1025–1035. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zähringer, U., Y. A. Knirel, E. T. Rietschel, R. Marre, and J. Helbig. 1994. Chemical structure and epitope specificity of the O-specific chain of on Legionella pneumophila (strain Philadelphia 1) lipopolysaccharide. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 40(Suppl. 63):44.

- 46.Zähringer U, Knirel Y A, Lindner B, Helbig J H, Sonesson A, Marre R, Rietschel E T. The lipopolysaccharide of Legionella pneumophilaserogroup 1 (strain Philadelphia 1): chemical structure and biological significance. Prog Clin Res. 1995;392:113–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziegler-Heitbrock H W L, Thiel E, Fütterer A, Herzof V, Wirtz A, Riethmüller G. Establishment of a human cell line (Mono Mac 6) with characteristics of mature monocytes. Int J Cancer. 1988;41:456–461. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910410324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ziegler-Heitbrock H W L, Blumenstein M, Käfferlein E, Kieper D, Petersmann I, Endres S, Flegel W A, Northoff H, Riethmüller G, Haas J G. In vitro desensitization to lipopolysaccharide suppresses tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 gene expression in a similar fashion. Immunology. 1992;75:264–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ziegler-Heitbrock H W L. Molecular mechanisms in tolerance to lipopolysaccharide. J Inflamm. 1995;45:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]