Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) have been repeatedly demonstrated to have worse clinical outcomes compared to patients without DM. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of DM on 1-year clinical outcomes after isolated CABG.

METHODS

The European DuraGraft registry included 1130 patients (44.6%) with and 1402 (55.4%) patients without DM undergoing isolated CABG. Intra-operatively, all free venous and arterial grafts were treated with an endothelial damage inhibitor. Primary end point in this analysis was the incidence of a major adverse cardiac event (MACE), a composite of all-cause death, repeat revascularization or myocardial infarction at 1 year post-CABG. To balance between differences in baseline characteristics (n = 1072 patients in each group), propensity score matching was used. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to identify independent predictors of MACE.

RESULTS

Diabetic patients had a higher cardiovascular risk profile and EuroSCORE II with overall more comorbidities. Patients were comparable in regard to surgical techniques and completeness of revascularization. At 1 year, diabetics had a higher MACE rate {7.9% vs 5.5%, hazard ratio (HR) 1.43 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.95], P = 0.02}, driven by increased rates of death [5.6% vs 3.5%, HR 1.61 (95% CI 1.10–2.36), P = 0.01] and myocardial infarction [2.8% vs 1.4%, HR 1.99 (95% CI 1.12–3.53) P = 0.02]. Following propensity matching, no statistically significant difference was found for MACE [7.1% vs 5.7%, HR 1.23 (95% CI 0.87–1.74) P = 0.23] or its components. Age, critical operative state, extracardiac arteriopathy, ejection fraction ≤50% and left main disease but not DM were identified as independent predictors for MACE.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, 1-year outcomes in diabetics undergoing isolated CABG were comparable to patients without DM.

Keywords: Coronary artery bypass grafting, Diabetes mellitus, Endothelial damage inhibitor, Graft failure

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide [1].

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide [1]. One of its classical risk factors is diabetes mellitus (DM), which is present in almost 40% of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) [2]. There is growing evidence that patients with DM specifically benefit from CABG compared to medical treatment or percutaneous interventions [3].

However, in patients with DM, short- and long-term graft patency rates may be lower due to their underlying disease compared to patients without DM [no diabetes mellitus (NDM)]. Early graft failure post-CABG has been reported to be as high as 12% [4]. Short- and long-term patency, especially of saphenous vein grafts (SVGs), may be related to endothelial damage caused by different triggers [5].

Attempts have been made to inhibit endothelial damage, particularly in SVGs, by modifying the harvesting technique or by external support [6–8]. Recently, an endothelial damage inhibitor (EDI) has been introduced [9–13]. It is hoped that this agent can preserve the functionality and integrity of endothelial and intimal structure [14], thereby providing potential benefits on graft patency. As this may be of increased clinical importance in patients with DM, we here evaluated the impact of DM on 1-year clinical outcomes after isolated CABG.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Ethics approval

The analysis complied with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee at each site. The first ethical committee approval was received on 28 September 2016 in Vitoria, Spain (No.: PI2016118) and consecutively at all other centres. All patients provided written informed consent. The clinicaltrial.gov identifier is NCT02922088.

Study design and patient population

The design of the DuraGraft multicentre Registry has been described earlier [10].

In brief, 2964 patients (aged ≥18 years) who underwent isolated CABG or combined CABG plus valve procedure with at least 1 or more SVGs or at least 1 or more free arterial graft(s) were enrolled from December 2016 to August 2019 at 45 hospitals in 8 European countries. DuraGraft was applied intra-operatively on all SVGs and free arterial grafts. Surgical techniques, including the selection of on- or off-pump approaches, harvesting technique or grafting configuration, were left to the discretion of the performing surgeon.

For this study, a sub-analysis of patients undergoing isolated CABG was selected and grouped according to the presence of DM. In total, 2532 patients underwent isolated CABG, of whom 1130 (44.6%) had DM and 1,402 (55.4%) had NDM. Patient follow-up was performed at 30 days and 1 year by a visit to the outpatient clinic or by phone.

Graft treatment

After harvest, and prior to anastomosis, SVGs and free arterial conduits of all patients (n = 2532) were flushed and stored in DuraGraft (Marizyme, Jupiter, Florida, USA), an EDI in order to protect the structure and the function of the graft endothelium against ischaemic and reperfusion damage [9]. In brief, the DuraGraft solution comes in 2 containers with separate constituents that are mixed at the time of the procedure to formulate into an ionically and pH-balanced physiological salt solution containing glutathione, l-ascorbic acid and l-arginine as an antioxidant and generator of nitric oxide [10].

End points and adjudication

The primary outcome measure was the incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as the composite of death, repeat revascularization (RR) or myocardial infarction (MI). Major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE), a composite of death, MI, RR or stroke were defined as secondary end point. Definitions of clinical events are described in the Supplementary Material, Appendix. An independent clinical events committee comprised of 2 interventional cardiologists adjudicated all primary and secondary outcome-related adverse events in a consensus meeting.

Statistical analysis

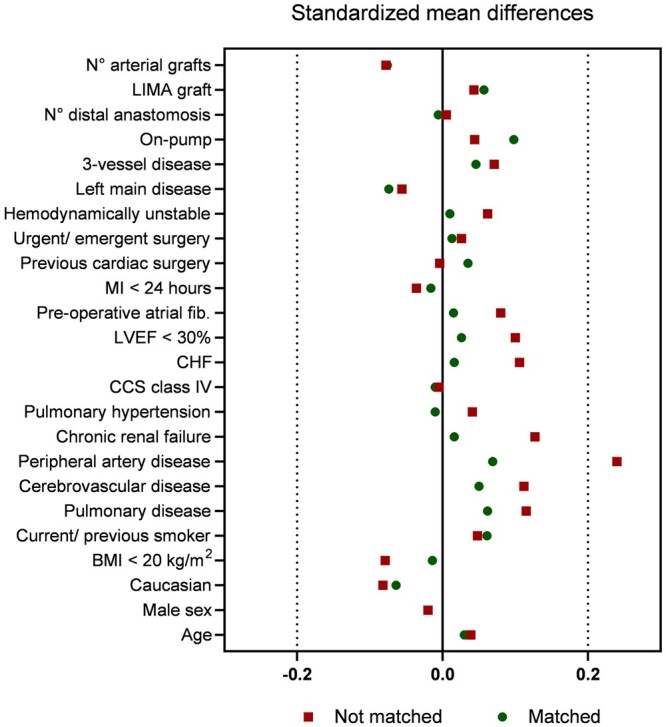

Continuous and categorial variables are reported as mean and standard deviations or frequency and percentages, respectively. The student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables and chi-squared testing was used to compare categorical variables. The primary analyses for comparing diabetic and non-diabetic groups were based on Propensity score matching. For propensity score matching (PSM), baseline demographic variables (please see Supplementary Material, Appendix) were chosen a priori to match diabetic and non-diabetic patients using a 1:1 greedy-match algorithm. Matching was based upon the logit of the propensity score using a calliper of 0.20. In total, 1072 (94.5%) of 1130 diabetic patients were matched with a non-diabetic patient for a total sample size of 2144 participants. Standardized differences of <10% were used to determine the covariate balance between propensity-matched groups (Fig. 1). Cox proportional hazards regression modelling was carried out before and after propensity match, In matched analyses, Cox proportional hazards regression modelling was stratified on the matched pair. Proportional hazards assumption across diabetes groups was tested in the unmatched cohort. Event rates were calculated using Kaplan–Meier methods prior to propensity match. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used as sensitivity analysis for comparing diabetic and non-diabetic groups after adjusting for confounders. The multivariable model was built with candidate variables (Supplementary Material, Appendix) selected as confounders.

Figure 1:

Standardized mean differences in covariates included in the propensity score matching.

Since outcome measures considered in this article are time-top-event, no imputation was done for outcome data. Subject outcome data were censored at their last known time in the study. Missing data in covariates were imputed using mean imputation. Specifically, the mean of the observed values for each covariate is computed and the missing values for that covariate were imputed by this mean.

A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate significance. All analyses were done with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Patient baseline and procedural characteristics before and after propensity matching

Patient baseline characteristics before and after propensity matching are presented in Table 1. In the unmatched comparison, DM patients had a higher body mass index (29.3 ± 4.7 vs 28.0 ± 4.2, P < 0.001), more frequent hypertension (88.2% vs 81.7%, P < 0.001) and dyslipidaemia (82.0% vs 72.9%, P < 0.001) and presented with more frequent end-organ disease such as severe renal impairment (13.5% vs 9.8%, P = 0.01), cerebrovascular disease (10.2% vs 7.1%, P = 0.01) and peripheral vascular disease (21.3% vs 12.4%, P < 0.001). DM patients presented with an overall lower ejection fraction (P < 0.01) and a higher median EuroSCORE II [1.6 (IQR: 1.0–2.7) vs 1.3 (0.9–2.1), P < 0.001]. After matching patient characteristics were well balanced (Table 1).

Table 1:

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching

| Subject characteristic | Before PSM |

After PSM |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | No DM | P-value | DM | No DM | P-value | |

| n = 1130 | n = 1402 | n = 1072 | n = 1072 | |||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 67.6 ± 8.5 | 67.2 ± 9.7 | 0.33 | 67.5 ± 8.6 | 67.2 ± 9.9 | 0.49 |

| Male (%) | 82.0 | 82.8 | 0.64 | 82.2 | 82.3 | 1.00 |

| Caucasian ethnicity (%) | 86.4 | 89.1 | 0.04 | 87.2 | 89.3 | 0.16 |

| Body mass index <20 kg/m2 (%) | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.00 |

| (Ex-)smoker (%) | 63.4 | 61.1 | 0.25 | 63.2 | 60.2 | 0.17 |

| Pulmonary disease (%) | 16.1 | 12.1 | 0.01 | 14.8 | 12.7 | 0.17 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 10.2 | 7.1 | 0.01 | 9.2 | 7.8 | 0.28 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 21.3 | 12.4 | <0.001 | 17.2 | 14.6 | 0.13 |

| Chronic renal failurea (%) | 4.8 | 2.4 | 0.001 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 0.81 |

| Pulmonary hypertension (%) | 8.8 | 7.6 | 0.31 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 0.88 |

| CCS class IV (%) | 8.8 | 9.0 | 0.94 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 0.88 |

| Ejection fraction <30% (%) | 6.2 | 4.0 | 0.01 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 0.62 |

| Previous MI (%) | 43.7 | 41.4 | 0.25 | 42.9 | 41.1 | 0.40 |

| Previous cardiac surgery (%) | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.92 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.54 |

| Urgent/emergent surgery (%) | 26.0 | 24.9 | 0.52 | 25.3 | 24.7 | 0.80 |

| Haemodynamically unstable/cardiac shock (%) | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.14 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.00 |

| Left main disease (%) | 39.6 | 42.4 | 0.16 | 39.4 | 43.0 | 0.10 |

| Three (3)-vessel disease (%) | 83.2 | 80.5 | 0.08 | 82.7 | 81.0 | 0.31 |

| On-pump surgery (%) | 83.8 | 82.2 | 0.28 | 84.0 | 80.3 | 0.03 |

| Number of total distal anastomoses, mean ± SD | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 0.90 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 0.88 |

| LIMA graft (%) | 93.5 | 92.4 | 0.28 | 93.5 | 92.0 | 0.21 |

| Number of arterial grafts, mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.08 |

Chronic lung disease: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema and asthma.

Chronic renal failure defined as on haemodialysis or a preoperative creatinine value >2.0 mg/day.

CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; DM: diabetes mellitus; LIMA: left internal mammary artery; MI: myocardial infarction; PSM: propensity score matching; SD: standard deviation.

Surgical technique

Operative approach, vein harvesting technique or graft use were similar between groups, except for decreased right internal mammary artery use in DM patients (15.0% vs 19.9%, P = 0.001). Importantly, the degree of achieved complete revascularization was similar between groups (81.8% vs 80.4%, P = 0.35) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Surgical characteristics

| DM, n = 1130 | No DM, n = 1402 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative status (%) | 0.80 | ||

| Elective | 74.0 | 75.1 | |

| Urgent | 24.7 | 23.5 | |

| Emergency | 1.3 | 1.4 | |

| Full sternotomy (%) | 99.6 | 99.8 | 0.50 |

| Off-pump (%) | 16.2 | 17.8 | 0.28 |

| Vein harvesting technique (%) | 0.29 | ||

| Open | 73.1 | 70.7 | |

| Endo | 14.1 | 15.3 | |

| Bridge technique | 7.9 | 9.6 | |

| Both open and endo | 3.6 | 2.7 | |

| No touch | 1.3 | 1.7 | |

| Graft use (%) | |||

| Saphenous vein | 90.6 | 88.8 | 0.14 |

| LIMA | 93.5 | 92.4 | 0.28 |

| RIMA | 15.0 | 19.9 | 0.001 |

| Radial artery | 10.9 | 11.6 | 0.60 |

| Number of grafts/patient | 2.74 ± 0.79 | 2.74 ± 0.79 | 0.93 |

| Number of arterial grafts/patient | 1.20 ± 0.55 | 1.24 ± 0.62 | 0.05 |

| Number of vein grafts/patient | 1.54 ± 0.88 | 1.49 ± 0.89 | 0.17 |

| Number of distal anastomoses | 3.02 ± 0.88 | 3.01 ± 0.89 | 0.90 |

| Coronary territory supplied (%) | |||

| Left anterior descending | 96.1 | 94.7 | 0.10 |

| Circumflex | 83.1 | 84.3 | 0.42 |

| Right coronary artery | 71.7 | 69.3 | 0.19 |

| Complete revascularization (%) | 81.8 | 80.4 | 0.35 |

DM: diabetes mellitus; LIMA: left internal mammary artery; RIMA: right internal mammary artery.

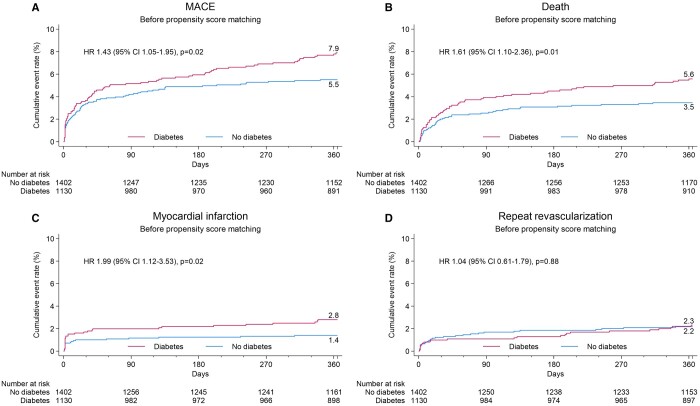

Clinical outcomes in the unmatched cohorts

The Kaplan–Meier estimate of the 1-year MACE was higher in the DM group {7.9% vs 5.5%, hazard ratio (HR) 1.43 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.95] P = 0.02}, driven by a higher all-cause death rate [5.6% vs 3.5%, HR 1.61 (95% CI 1.10–2.36), P = 0.01] and higher rate of MI [2.8% vs 1.4%, HR 1.99 (95% CI 1.12–3.53), P = 0.02] (Fig. 2 and Table 3). No difference in RR was detected [2.3% vs 2.2%, HR 1.04 (95% CI 0.61–1.79), P = 0.88]. There was a trend for more cardiovascular deaths in the DM group [4.6% vs 3.1%, HR 1.50 (95% CI 0.99–2.26), P = 0.05]. Non-cardiovascular deaths were also numerically higher in the DM group without however reaching statistical significance [1.0% vs 0.4%, HR 2.55 (95% CI 0.87–7.46), P = 0.09].

Figure 2:

Cumulative event curves for isolated coronary artery bypass grafting patients with and without diabetes mellitus before propensity score matching. Major adverse cardiac event, all death, myocardial infarction and repeat revascularization.

Table 3:

Cumulative cardiac event rate by Kaplan–Meier method at 1 year before propensity score matching

| DM | No DM | HR ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1130 | n = 1402 | |||

| MACE, % (n) | 7.9 (85) | 5.5 (75) | 1.43 (1.05–1.95) | 0.02 |

| MACCE, % (n) | 9.0 (97) | 6.8 (93) | 1.31 (0.99–1.74) | 0.06 |

| All death, % (n) | 5.6 (60) | 3.5 (47) | 1.61 (1.10–2.36) | 0.01 |

| Cardiovascular death, % (n) | 4.6 (50) | 3.1 (42) | 1.50 (0.99–2.26) | 0.05 |

| Non-cardiovascular death, % (n) | 1.0 (10) | 0.4 (5) | 2.55 (0.87–7.46) | 0.09 |

| MI, % (n) | 2.8 (30) | 1.4 (19) | 1.99 (1.12–3.53) | 0.02 |

| Repeat revascularization, % (n) | 2.3 (24) | 2.2 (29) | 1.04 (0.61–1.79) | 0.88 |

| PCI, % (n) | 2.1 (22) | 1.7 (23) | 1.21 (0.67–2.17) | 0.52 |

| Surgical revascularization, % (n) | 0.2 (2) | 0.4 (6) | 0.42 (0.08–2.06) | 0.28 |

| Stroke, % (n) | 1.8 (20) | 1.9 (26) | 0.97 (0.54–1.73) | 0.91 |

HRs and P-values are calculated for diabetes versus no diabetes from a Cox proportional hazards model with treatment as only explanatory variable

CI: confidence interval; DM: diabetes mellitus; HR: hazard ratio; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebral event; MACE: major adverse cardiac event; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

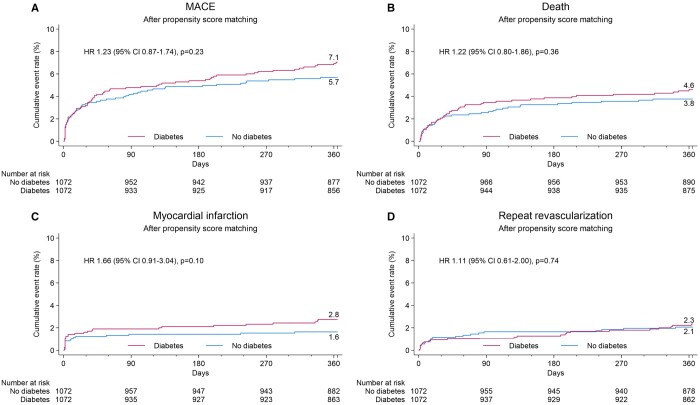

Clinical outcomes after propensity matching

The cumulative cardiac event rate by Kaplan–Meier method at 30 days and 1 year after PSM is depicted in Fig. 3 and Table 4.

Figure 3:

Cumulative event curves for isolated coronary artery bypass grafting patients with and without diabetes mellitus after propensity score matching. Major adverse cardiac event, all death, myocardial infarction and repeat revascularization.

Table 4:

Cumulative cardiac event rate by Kaplan–Meier method at 1 year after propensity score matching

| DM | No DM | HR ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1072 | n = 1072 | |||

| MACE, % (n) | 7.1 (72) | 5.7 (59) | 1.23 (0.87–1.74) | 0.23 |

| MACCE, % (n) | 8.0 (82) | 7.2 (75) | 1.10 (0.81–1.51) | 0.56 |

| All death, % (n) | 4.6 (47) | 3.8 (39) | 1.22 (0.80–1.86) | 0.36 |

| Cardiovascular death, % (n) | 4.0 (41) | 3.3 (34) | 1.22 (0.77–1.92) | 0.40 |

| Non-cardiovascular death, % (n) | 0.6 (6) | 0.5 (5) | 1.22 (0.37–4.00) | 0.74 |

| MI, % (n) | 2.8 (28) | 1.6 (17) | 1.66 (0.91–3.04) | 0.10 |

| Repeat revascularization, % (n) | 2.3 (23) | 2.1 (21) | 1.11 (0.61–2.00) | 0.74 |

| PCI, % (n) | 2.1 (21) | 1.8 (18) | 1.18 (0.63–2.22) | 0.60 |

| Surgical revascularization, % (n) | 0.2 (2) | 0.3 (3) | 0.67 (0.11–4.01) | 0.66 |

| Stroke, % (n) | 1.6 (17) | 2.2 (23) | 0.74 (0.40–1.39) | 0.35 |

HRs and P-values are calculated for diabetes versus no diabetes from a Cox proportional hazards model with treatment as only explanatory variable.

CI: confidence interval; DM: diabetes mellitus; HR: hazard ratio; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebral event; MACE: major adverse cardiac event; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

In the PSM population (n = 1072 patients per group), MACE event rates at 1 year were similar between both groups [7.1% vs 5.7%, HR 1.23 (95% CI 0.87–1.74), P = 0.23] or its components. Stroke rates were also similar, leading to a comparable MACCE rate of 8.0% in the DM group compared to 7.2% in the NDM group [HR 1.10 (95% CI 0.81–1.51), P = 0.56] (Supplementary Material, Figs S1 and S2). At 30 days, there were no differences in event rates between the DM and NDM groups both before and after PSM (Supplementary Material, Tables S1 and S2).

Assessment of independent predictors for major adverse cardiac event

HRs for clinical events at 1 year comparing DM and NDM patients before and after matching are provided in Table 5. Multivariable analysis showed that age (per increments of 10 years), extracardiac arteriopathy, critical operative state, ejection fraction ≤50% and left main disease but not DM were independent predictors for MACE at 1 year after adjustment (Table 5).

Table 5:

Predictors for a major adverse cardiac event at 1 year before and after propensity score adjustment by multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis method

| Univariable models |

Multivariable models |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | <0.01 |

| Female sex | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.39 | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 0.67 |

| Urgency | ||||

| Urgent versus elective | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.02 | 0.9 0.6–1.3) | 0.64 |

| Emergency versus elective | 3.5 (1.5–8.0) | <0.01 | 1.6 (0.6–4.3) | 0.37 |

| CABG and valve surgery | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.02 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.19 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 0.04 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.75 |

| Renal impairment | ||||

| Moderate versus normal | 1.5 (1.8–2.2) | 0.02 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.62 |

| Severe versus normal | 2.9 (1.9–4.5) | <0.0001 | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | 0.13 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | 2.1 (1.5–3.0) | <0.0001 | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.01 |

| Poor mobility due to any non-cardiac reason | 1.7 (0.9–3.0) | 0.09 | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.51 |

| COPD/emphysema/asthma | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | 0.07 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.46 |

| CCS class 4 | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) | <0.01 | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) | 0.27 |

| NYHA grade pre-surgery | ||||

| Class II versus class I | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.43 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.61 |

| Class III versus class I | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | <0.01 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 0.24 |

| Class IV versus class I | 3.2 (1.7–6.0) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.5–2.6) | 0.79 |

| MI in last 90 days | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.01 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.13 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 2.1 (0.8–5.6) | 0.15 | 1.4 (0.4–4.6) | 0.54 |

| LVEF <50% | 2.1 (1.5–2.8) | <0.0001 | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | 0.001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 2.1 (1.4–3.2) | 0.001 | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) | 0.09 |

| Critical preoperative state | 4.4 (2.6–7.4) | <0.0001 | 2.5 (1.4–4.7) | <0.01 |

| Left main disease | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) | <0.01 | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.01 |

| Saphenous veins only | 1.7 (1.0–3.0) | 0.06 | 1.1 (0.5–2.1) | 0.85 |

| Arterial graft only | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.64 | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 0.21 |

| On pump surgery versus not | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | 0.87 | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | 0.94 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive lung disease; HR: hazard ratio; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MI: myocardial infarction; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

DISCUSSION

In this sub-analysis of a large European multicentre registry of coronary bypass graft treatment with an EDI (DuraGraft), patients with DM undergoing isolated CABG had poorer postoperative outcomes compared to patients with NDM represented by 1-year MACE. However, after propensity matching, MACE and MACCE did not show any statistical difference.

Previous studies [15] demonstrated, and current guidelines recommend that CABG be the preferred treatment for patients with complex coronary artery disease [3, 16]. This is especially true for patients with DM, with all coronary arteries affected. It is well known that DM increases operative risk especially if preoperative glycometabolic status is poor [17–19].

Our results from >2500 patients mirror these general findings; patients with DM represent a higher-risk group with worse postoperative outcomes. In the present study, patients with DM had more frequent arterial hypertension and dyslipidaemia, extracardiac vasculopathies and impaired renal function affecting the EuroSCORE II, which was higher compared to NDM patients. In the unmatched, crude analysis, MACE at 1 year was higher in the DM group, driven by a higher rate of all-cause mortality and a higher rate of MI.

Besides the impact of DM on postoperative outcome, early vein graft failure remains considerably high in DM as well as in NDM patients [4, 20]. It is speculated that endothelial damage during SVG harvesting and exposure to coronary artery haemodynamics plays an important role [21, 22]. Attempts have been made to overcome these problems by modifying the harvesting technique [21] or supporting the SVG externally [7, 8]. With regard to SVGs used in the current study, we can exclude that the harvesting technique influenced early outcome as it was comparable in both groups. Completeness of revascularization and total number of grafts were also similar in both groups. There were less right internal mammary artery grafts used in the DM group, most likely attributed to the concern of an increased risk of wound complications, although there is some evidence that the use of bilateral IMA is beneficial [3], including in patients with DM [23–25].

In the current study, all free vascular grafts (SVGs and free arterial grafts) were treated with the EDI as part of a European multicentre, observational registry [10]. This agent was evaluated with a potential benefit for short- and long-term graft performance. Preservation of the endothelial integrity may be speculated to benefit clinical outcomes, and in DM patients with a higher risk of bypass graft failure and reduced graft patency, this may be of even greater relevance. We expected that DM patients with a higher risk profile and end-organ disease reflected in a higher EuroSCORE II would have poorer early postoperative outcome compared to NDM patients. In the unmatched, crude analysis, the DM group demonstrated an increased rate of MACE driven by a higher incidence of all-cause death and MI.

However, after PSM, no difference was seen between the matched cohorts with similar rates of MACE and MACCE at 1 year. Similarly, the survival in the DM group was not significantly poorer. It could therefore be speculated that endothelial preservation of venous and arterial grafts may have positively impacted early graft performance and clinical outcomes in diabetic patients, as the expected difference in DM and NDM groups diminished after propensity matching of patients.

It remains unclear whether comparable outcomes of DM and NDM patients are exclusively attributed to the effect of intraoperative graft treatment. However, lack of the anticipated poorer outcome in DM patients in this large, multicentre representative cohort is notable and therefore requires further long-term investigation.

Limitations

There are limitations of the study due to the observational study design and variations in performing CABG at the many European centres. However, our patient data represent a real-world scenario with different operative strategies, including use of arterial grafts, operative technique (e.g. on-pump, off-pump) and graft harvesting. Second, while this study focused on early postoperative outcomes (1 year), longer-term follow-up studies are needed to validate these findings. Third, every patient should have undergone graft assessment intra-operatively using flow measurement, which was, however, not systematically performed. Fourth, imaging assessment (e.g. computed tomography angiography) would have been required to assess the impact of the EDI on graft patency and should be pursued in future studies. Finally, the registry protocol did not specifically mandate for the evaluation of individual DM treatment regimens or the assessment and comparison of secondary parameters that may be associated to or triggered by diabetes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in this large multicentre European registry, DM was not identified as an independent risk factor for 1-year MACE. This study may further provide encouraging data on the hypothesis that preservation of bypass grafts with an EDI in patients with DM undergoing isolated CABG may positively affect outcomes, as these patients are known to have a higher cardiovascular risk profile and poorer outcome. Further randomized studies to clarify the potential benefit of an EDI for long-term graft patency and for the subgroup of DM patients are needed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are thankful to Clara Vitarello, MPH, at Boston Clinical Research Institute (BCRI), Boston, MA, USA, for the statistical analysis.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CI

Confidence interval

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- EDI

Endothelial damage inhibitor

- HR

Hazard ratio

- MACCE

Major adverse cardiac and cerebral events

- MACE

Major adverse cardiac events

- MI

Myocardial Infarction

- NDM

No diabetes mellitus

- RR

Repeat revascularization

- SVGs

Saphenous vein grafts

Contributor Information

Martin Misfeld, University Department of Cardiac Surgery, Leipzig Heart Center, Leipzig, Germany; Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Institute of Academic Surgery, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia; The Baird Institute of Applied Heart and Lung Surgical Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Medical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

Sigrid Sandner, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Vienna General Hospital, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Etem Caliskan, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany; Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, Deutsches Herzzentrum der Charite (DHZC), Berlin, Germany.

Andreas Böning, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Medical Faculty, Justus-Liebig-University Giessen, Giessen, Germany.

Jose Aramendi, Hospital de Cruces, Barakaldo, Spain.

Sacha P Salzberg, Swiss Ablation, Herz & Rhythmus Zentrum AG, Zurich, Switzerland.

Yeong-Hoon Choi, Kerckhoff Heart Center, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Bad Nauheim, Germany.

Louis P Perrault, Montreal Heart Institute, Montreal, Canada.

Ilker Tekin, Manavgat Government Hospital, Manavgat, Turkey; Bahçeşehir University Faculty of Medicine, İstanbul, Turkey.

Gregorio P Cuerpo, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Jose Lopez-Menendez, Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, Spain.

Luca P Weltert, European Hospital, Rome, Italy.

Alejandro Adsuar-Gomez, Virgen del Rocio University Hospital, Seville, Spain.

Matthias Thielmann, West-German Heart and Vascular Center, University Hospital Essen, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany.

Giuseppe F Serraino, Magna Graecia University of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy.

Gheorghe Doros, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA.

Michael A Borger, University Department of Cardiac Surgery, Leipzig Heart Center, Leipzig, Germany.

Maximilian Y Emmert, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany; Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, Deutsches Herzzentrum der Charite (DHZC), Berlin, Germany.

European DuraGraft Registry investigators:

Sigrid Sandner, Daniel Zimpfer, Ulvi Cenk Oezpeker, Michael Grimm, Bernhard Winkler, Martin Grabenwöger, Michaele Andrä, Anas Aboud, Stephan Ensminger, Martin Misfeld, Michael A Borger, Andreas Böning, Bernd Niemann, Tomas Holubec, Arnaud Van Linden, Matthias Thielmann, Daniel Wendt, Assad Haneya, Katharina Huenges, Johannes Böhm, Markus Krane, Etem Caliskan, Herko Grubitzsch, Farhad Bakthiary, Jörg Kempfert, Adam J Penkalla, Bernhard C Danner, Fawad A Jebran, Carina Benstoem, Andreas Goetzenich, Christian Stoppe, Elmar W Kuhn, Yeong-Hoon Choi, Oliver J Liakopoulos, Stefan Brose, Klaus Matschke, Dave Veerasingam, Kishore Doddakula, Luca P Weltert, Lorenzo Guerrieri Wolf, Giuseppe Filiberto Serraino, Pasquale Mastroroberto, Nicola Lamascese, Massimo Sella, Jose Lopez-Menendez, Edmundo R Fajardo-Rodriguez, Jose I Aramendi, Alejandro Crespo, Angel L Fernandez Gonález, Gregorio P Cuerpo, Alvaro Pedraz, José M González-Santos, Elena Arnáiz-García, Ignacio Muñoz Carvajal, Adrian J Fontaine, José Ramón González Rodríguez, José Antonio Corrales Mera, Paloma Martinez, Jose Antonio Blazquez, Juan-Carlos Tellez, Bella Ramirez, Alejandro Adsuar-Gomez, Jose M Borrego-Dominguez, Christian Muñoz-Guijosa, Sara Badía-Gamarra, Rafael Sádaba, Alicia Gainza, Manuel Castellá, Gregorio Laguna, Javier A Gualis, Enrico Ferrari, Stefanos Demertzis, Sacha Salzberg, Jürg Grünenfelder, Robert Bauernschmitt, Ilker Tekin, Amal K Bose, Nawwar Al-Attar, and George Gradinariu

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at ICVTS online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Marizyme, Jupiter, Florida, USA.

Conflict of interest: Etem Caliskan, Martin Misfeld, Jose Aramendi, Sacha P. Salzberg, Yeong-Hoon Choi and Andreas Böning are members of the registry advisory committee (RAC). Louis P. Perrault is a member of the RAC and is a consultant for Marizyme. Maximilian Y. Emmert is the principal investigator of the registry, the chair of the RAC and a consultant for Marizyme. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data are held by the study sponsor and are available upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

Martin Misfeld: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Sigrid Sandner: Writing—review & editing. Etem Caliskan: Writing—review & editing. Andreas Böning: Writing—review & editing. Jose Aramendi: Writing—review & editing. Sacha P. Salzberg: Writing—review & editing. Yeong-Hoon Choi: Writing—review & editing. Louis P. Perrault: Writing—review & editing. Ilker Tekin: Writing—review & editing. Gregorio P. Cuerpo: Writing—review & editing. Jose Lopez-Menendez: Writing—review & editing. Luca P. Weltert: Writing—review & editing. Alejandro Adsuar-Gomez: Writing—review & editing. Matthias Thielmann: Writing—review & editing. Giuseppe F. Serraino: Writing—review & editing. Gheorghe Doros: Writing—review & editing. Michael A. Borger: Writing—review & editing. Maximilian Y. Emmert: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Reviewer information

Interdisciplinary CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery thanks Ari Mennander, Francesco Formica and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review process of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM. et al. ; GBD-NHLBI-JACC Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases Writing Group. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019 update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2982–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lüscher TF, Creager MA, Beckman JA, Cosentino F.. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: part II. Circulation 2003;108:1655–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sousa-Uva M, Neumann F-J, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U. et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revscularization. The Task Force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2019;55:4–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhao DX, Leacche M, Balaguer JM, Boudoulas KD, Damp JA, Greelish JP. et al. ; Writing Group of the Cardiac Surgery, Cardiac Anesthesiology, and Interventional Cardiology Groups at the Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute. Routine intraoperative completion angiography after coronary artery bypass grafting and 1-stop hybrid revascularization results from a fully integrated hybrid catheterization laboratory/operating room. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:232–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Caliskan E, de Souza DR, Böning A. et al. Saphenous vein grafts in contemporary coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020. Mar;17(3):155–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Angelini GD, Johnson T, Culliford L, Murphy G, Ashton K, Harris T. et al. Comparison of alternate preparative techniques on wall thickness in coronary artery bypass grafts: the HArVeST randomized controlled trial. J Card Surg 2021;36:1985–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Samano N, Souza D, Dashwood MR.. Saphenous veins in coronary artery bypass grafting need external support. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2021;29:457–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goldstein DJ. Device profile of the VEST for external support of SVG coronary artery bypass grafting: historical development, current status and future directions. Expert Rev Med Devices 2021;18:921–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haime M, McLean RR, Kurgansky KE, Emmert MY, Kosik N, Nelson C. et al. Relationship between intra-operative vein graft treatment with DuraGraft or saline and clinical outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2018;16:963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Caliskan E, Sandner S, Misfeld M, Aramendi J, Salzberg SP, Choi Y-H. et al. A novel endothelial damage inhibitor for the treatment of vascular conduits in coronary artery bypass grafting: a protocol and rationale for the European, multicenter, prospective, observational DuraGraft registry. J Cardiothoracic Surg 2019;14:174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aschacher T, Baranyi U, Aschacher O, Eichmair E, Messner B, Zimpfer D. et al. A novel endothelial damage inhibitor reduces oxidative stress and improves cellular integrity in radial artery for coronary artery bypass. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021;8:736503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ben Ali W, Voisine P, Olsen PS, Jeanmart H, Noiseux N, Goeken T. et al. DuraGraft vascular conduit preservation solution in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: rationale and design of a within-patient randomised multicentre trial. Open Heart 2018;5:e000780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sandner S, Misfeld M, Caliskan E.. et al. Clinical outcomes and quality of life after contemporary isolated coronary bypass grafting: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2023. Apr 1;109(4):707–715. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36912566/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nazari-Shafti TZ, Thau H, Zacharova E, Beez CM, Exarchos V, Neuber S et al. Endothelial damage inhibitor preserves the integrity of venous endothelial cells from patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2023;64(6):ezad327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perrault LP, Carrier M, Voisine P.. et al. Sequential multidetector computed tomography assessments after venous graft treatment solution in coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021. Jan;161(1):96–106.e2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31866081/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chang M, Ahn J-M, Lee CW, Cavalcante R, Sotomi Y, Onuma Y. et al. Long-term mortality after coronary revascularization in nondiabetic patients with multivessel disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kolh P, Kurlansky P, Cremer J, Lawton J, Siepe M, Fremes S.. Transatlantic editorial: a comparison between the European and North American guidelines on myocardial revascularization. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;152:304–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng J, Cheng J, Wang T, Zhang Q, Xiao X.. Does HbA1c level have clinical implications in diabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Endocrinol 2017;2017:1537213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang J, Luo X, Jin X, Lv M, Li X, Dou J. et al. Effect of preoperative HbA1c levels on the postoperative outcomes of coronary artery disease surgical treatment in patients with diabetes mellitus and nondiabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Res 2020;2020:3547491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corazzari C, Matteucci M, Kolodziejczak M, Kowalewski M, Formenti AM, Giustina A, et al. Impact of preoperative glycometabolic status on outcomes in cardiac surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022 Dec;164(6):1950–1960.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Antonopoulos AS, Odutayo A, Oikonomou EK, Trivella M, Petrou M, Collins GS. et al. ; SAFINOUS-CABG (Saphenous Vein Graft Failure—An Outcomes Study in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting) group. Development of a risk score for early saphenous vein graft failure: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;160:116–27.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Angelini GD, Passani SL, Breckenridge IM, Newby AC.. Nature and pressure-dependence of damage induced by distension of human saphenous-vein-coronary artery bypass grafts. Cardiovasc Res 1987;21:902–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guida G, Ward AO, Bruno VD, George SJ, Caputo M, Angelini GD. et al. Saphenous vein graft disease, pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment. A review of the literature. J Card Surg 2020;35:1314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhou P, Zhu P, Nie Z, Zheng S.. Is the era of bilateral internal thoracic artery grafting coming for diabetic patients? An updated meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;158:1559–70.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Formica F, Gallingani A, Tuttolomondo D, Hernandez-Vaquero D, D'Alessandro S, Singh G. et al. Very long-term outcome of bilateral internal thoracic artery in diabetic patients: a systematic review and reconstructed time-to-event meta-analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol 2024;49:102135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stefil M, Dixon M, Benedetto U, Gaudino M, Lees B, Gray A. et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting using bilateral internal thoracic arteries in patients with diabetes and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2023;47:101235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are held by the study sponsor and are available upon reasonable request.