Graphical abstract

Keywords: Respiration, Pressure, Flow, Obstructive, COPD, Resistance, End-Expiration

Abstract

Respiratory disease is a major contributor to healthcare costs, as well as increasing morbidity and early mortality. The device presented is used to simulate the effects of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) in healthy people. The intended use is to provide data equivalent to COPD data measured from those who are ill for initial validation of respiratory mechanics models. It would thus eliminate the need to test unhealthy and/or fragile subjects, or the need for invasive or costly equipment based test methods. The device is used in conjunction with an open-access venturi-based flow sensor, to measure pressure, flow, and breath tidal volume. The device simulates the pressure and flow profiles of a person who has COPD including the non-linear increased resistance to end-exhalation and gas trapping. To achieve this non-linearity, a combination of high and low resistance outlets is used. Thus, the simulator allows the collection of patient-specific COPD-like breathing data in a non-invasive manner from healthy subjects. The device is low-cost with the majority of the parts 3D printed using a Prusa mini 3D printer and PLA filament.

Specifications table

| Hardware name | Obstructive Respiratory Disease Simulation Module |

|---|---|

| Subject area | Engineering and materials science |

| Hardware type | Measuring physical properties and in-lab sensors |

| Closest commercial analog | No commercial analog is available. |

| Open source license | Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license |

| Cost of hardware |

∼ $60 NZD ∼$350 NZD for the data recording device (shutter not required) |

| Source file repository |

https://doi.org/10.17632/kk6hktdydg.3 Used in conjunction with components of a data recording device[1] |

| OSHWA certification UID (OPTIONAL) |

NZ000003 |

Hardware in context

Respiratory disease is a large contributor to healthcare costs in New Zealand, costing ∼ 6.68 billion dollars in 2017, and accounts for 6.3 % of total health loss in New Zealand [2]. COPD is one of the largest contributors to this total health loss at 3.7 % followed by asthma at 1.6 % [3]. The COPD simulation device presented is designed to avoid having to test unhealthy and/or fragile subjects, while minimising the need for invasive or equipment-specific tests, which usually come at a far higher time and economic cost. It is designed to be used in conjunction with an open-access venturi-based flow sensor [1], [4], to measure pressure, flow, and breath tidal volume, which can then be used to replicate COPD pressure-flow loops from healthy subjects with much lower cost and risk.

More specifically, the validation of respiratory models for COPD currently requires clinical testing on unhealthy people with the disease and the potential use of invasive or difficult to perform maneuvers and methods. The development of a system or device to simulate respiratory disease in healthy individuals would reduce the need for these methods and unhealthy test subjects, reducing risk and cost. Respiratory models have the potential to be used to determine patient-specific mechanical ventilation settings [5], [6], [7]. Mechanical ventilation settings are traditionally determined by the clinician [8], [9], so accurate predictive respiratory models have the potential to assist clinicians to make this decision and provide better patient-specific care [6], [10], [11], [12], [13].

There are two current categories of respiratory disease simulation devices on the market. The first category are devices that simulate the symptoms of respiratory disease in healthy people. The second category are artificial lung devices that simulate pressure, flow, and volume profiles of respiratory disease. Devices in both categories are high cost (typically > US $850) and are not useful in the validation of respiratory models. In particular, devices that simulate the symptoms of respiratory disease in healthy people are not specific to COPD. The devices on the market in the first category predominantly focus on simulating the symptoms and feeling of having generalised respiratory distress rather than the specific dysfunctions present in diseases like COPD. Additionally, these devices do not generate the characteristic pressure, flow, and volume profiles that result from COPD. Thus, they are not helpful in the validation of respiratory models in the way the proposed devices intend. The devices in the second category produce the pressure and flow profiles required, but are not patient-specific meaning they cannot mimic inter- and intra- patient variabilities seen in clinical practice, where the device presented does provide these variabilities as they are obtained from individuals every breath. The device outlined in this article combines the benefits of both categories to result in a low-cost, non-invasive device that generates patient-specific pressure, flow, and volume profiles associated with COPD. The majority of the designed device is 3D printed and it is easily customisable to suit the required disease state. COPD is classified by the level of gas trapping and flow limitation [14]. The level of flow limitation in this device is determined by the high resistance outlet and the gas trapping by the free volume. Thus different disease states are able to be simulated by changing the free volume or high resistance outlet sizes. In this case severe COPD has been simulated with a high resistance outlet and large free volume but trial and error with changing these would allow a multitude of different disease states to be simulated.

Hardware description

The designed COPD simulation device is low-cost, non-invasive, and customisable. The intended use of this device is to simulate COPD in conjunction with measurements of airway pressure, flow, and volume using either a y-split flow sensor system [1], or a simpler venturi design approach and only exhaling through the device [4], [15]. The assembly is designed to be used with or without a constant positive airway pressure (CPAP) device to provide additional positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), a common form of treatment therapy for COPD [16], [17], [18]. To simulate both the symptoms and characteristic flow profiles of COPD the device uses a combination of high and low resistance outlets. The device is attached to the exhalation side of the flow sensor y-split. Attaching the device to only the exhalation side allows inhalation to remain unchanged. COPD only effects exhalation a key feature other devices on the market don’t include. During exhalation air first enters the low resistance free volume chamber, as pressure increases in the chamber the air is diverted out the high resistance outlet. This diversion creates a non-linearity in resistance, characteristic of COPD, with an increased resistance to end-exhalation. The non-linearity is a key difference of this device from those currently available, as it creates the required flow profiles, rather than just simulating an obstruction. Equally, it does so based on a subject-specific breath.

As this device is 3D printed, it is easily customisable in almost all design aspects. This project demonstrates three different free volume chamber sizes (200 mL, 250 mL, and 300 mL), but is generalisable to a very wide range and resolution. Additionally, the resistance of the high resistance outlet can be changed by changing the size of the hole, and is again generalisable and controls, in part, how fast the free volume fills. Customising this device has the potential to mimic multiple different disease states (modes and progressions).

Overall, the device is able to simulate COPD for the use of preliminary development and respiratory model validation by using a combination of fixed high and low resistance outlets. The device can be useful as an initial tool as the data collected allows comparison of healthy data and simulated COPD from the same subject. The simulation and data collection is also, non-invasive, does not burden unhealthy people, can be modified to suit multiple applications by changing either the high resistance outlet or free volume chamber size.

-

-

Non-invasive, low-cost, patient specific COPD simulation

-

-

Respiratory model validation

-

-

Non-invasive data collection

-

-

3D printed and customisable

Design files summary

Table 1 outlines the design files for the simulation device, the type of file is indicated in the table. The categories of files are: 3D Printed Hardware (both CAD and STL file). Both the CAD and STL files are provided for the 3D printed components to allow modifications and ability to use for multiple applications. The data collection used code was taken from the flow sensor design [1].

Table 1.

Design file summary.

| Design file name | File type | Open source license | Location of the file |

|---|---|---|---|

| COPD_CoverLid | CAD (SLDPRT) and STL files | CC BY 4.0 | 3D Printed Hardware |

| CODP_Cover_300mL_20-02–23 | CAD (SLDPRT) and STL files | CC BY 4.0 | 3D Printed Hardware |

| CODP_Cover_250mL_20-02–23 | CAD (SLDPRT) and STL files | CC BY 4.0 | 3D Printed Hardware |

| CODP_Cover_200mL_20-02–23 | CAD (SLDPRT) and STL files | CC BY 4.0 | 3D Printed Hardware |

| COPD_LowResPathAdaptor_Female | CAD (SLDPRT) and STL files | CC BY 4.0 | 3D Printed Hardware |

| COPD_HighResPathCap_2mm | CAD (SLDPRT) and STL files | CC BY 4.0 | 3D Printed Hardware |

| COPD_ExpiratoryYJunction | CAD (SLDPRT) and STL files | CC BY 4.0 | 3D Printed Hardware |

Bill of materials summary

Table 2 outlines the bill of materials required to build the COPD simulation device with component name, number or amount required, cost per unit (NZD), total cost (NZD), source of materials, and material type.

Table 2.

Design file bill of materials (cost in NZD).

| Designator | Component | Number | Cost per Unit | Total Cost | Source of Materials | Material Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD_CoverLid | 1.75 mm PLA + 3D Filament | 3 (216.75 g) | $27.00/1kg | $17.51 | https://www.wondershop.nz/i/100000–100016.html | Polymer |

| COPD_Cover_300mL_20-02–23 | 1.75 mm PLA + 3D Filament | 1 (273.59 g) | $27.00/1kg | $7.39 | https://www.wondershop.nz/i/100000–100016.html | Polymer |

| COPD_Cover_250mL_20-02–23 | 1.75 mm PLA + 3D Filament | 1 (261.09 g) | $27.00/1kg | $7.05 | https://www.wondershop.nz/i/100000–100016.html | Polymer |

| COPD_Cover_200mL_20-02–23 | 1.75 mm PLA + 3D Filament | 1 (249.57 g) | $27.00/1kg | $6.74 | https://www.wondershop.nz/i/100000–100016.html | Polymer |

| COPD_LowResPathAdapter_Female | 1.75 mm PLA + 3D Filament | 1 (242.36 g) | $27.00/1kg | $6.54 | https://www.wondershop.nz/i/100000–100016.html | Polymer |

| COPD_HighResPathCap_2mm | 1.75 mm PLA + 3D Filament | 1 (205.89 g) | $27.00/1kg | $5.56 | https://www.wondershop.nz/i/100000–100016.html | Polymer |

| COPD_ExpiratoryYJunction | 1.75 mm PLA + 3D Filament | 1 (227.06 g) | $27.00/1kg | $6.13 | https://www.wondershop.nz/i/100000–100016.html | Polymer |

| M4 Nut | M4 Hex Nut | 6 | $0.14 | $0.84 | https://www.aliexpress.com/item/1005003780212966.html?spm = a2g0o.productlist.main.1.2d1bc76fUnhMi4&algo_pvid = 04364139-248a-4a51-9e53-14042b72e459&aem_p4p_detail = 202302221611244505149198006980003550505&algo_exp_id = 04364139-248a-4a51-9e53-14042b72e459-0&pdp_ext_f=%7B%22sku_id%22 %3A%2212000027143164251 %22 %7D&pdp_npi = 3 %40dis%21NZD%212.34 %211.67 %21 %21 %21 %21 %21 %4021227e5116771110847754832d06bf%2112000027143164251 %21sea%21NZ%210&curPageLogUid = zLQHnB6yBBRI&ad_pvid = 202302221611244505149198006980003550505_1&ad_pvid = 202302221611244505149198006980003550505_1 | Metal |

| M4 x 10 | 10 mm M4 Screw | 6 | $0.20 | $1.20 | https://www.aliexpress.com/item/1005002364189187.html?spm = a2g0o.productlist.main.1.344bb686QDXACO&algo_pvid = f773682b-8927-4d8f-ae47-4293ef6fbb1f&aem_p4p_detail = 20230222162028640361160391860003405370&algo_exp_id = f773682b-8927-4d8f-ae47-4293ef6fbb1f-0&pdp_ext_f=%7B%22sku_id%22 %3A%2212000020354274959 %22 %7D&pdp_npi = 3 %40dis%21NZD%216.44 %210.02 %21 %21 %21 %21 %21 %40211be59e16771116280258377d06f7%2112000020354274959 %21sea%21NZ%210&curPageLogUid = YYZK8uwM3yQf&ad_pvid = 20230222162028640361160391860003405370_1&ad_pvid = 20230222162028640361160391860003405370_1 | Metal |

| Latex Balloon | Microphone Cover/Non-lubricated Condom | 1 | $0.90 | $0.90 | https://www.ripnroll.com/products/microphone-covers | Latex |

| Zip Ties | Zip Ties | 2 | $0.02 | $0.04 | https://www.thewarehouse.co.nz/p/mako-cable-tie-set-400-piece/R2071900.html?&&&&gclsrc = aw.ds&ds_rl = 1268368&ds_rl = 1268368&gclid = CjwKCAjw5dqgBhBNEiwA7PryaIQ_OhaG5gSRLlhGlwuqjspGGUht5hfs0s5hjQhaMpOi31j7VpoSYBoCvh4QAvD_BwE&gclsrc = aw.ds | Polymer |

| Magnets | Counterweight | 2 | $3.50 | $7.00 | https://www.magnets.co.nz/shop/neodymium/rings-neodymium/10 mm-x-3 mm-x-3 mm-countersunk-neodymium-ring/?keyword_k=&gclid = CjwKCAjw5dqgBhBNEiwA7PryaOGnJmXKzldhj2UNtyhy6ePSA8sXF92vJWML05vm5AYXvwq2GmnQehoCTjwQAvD_BwE | Metal |

Build instructions

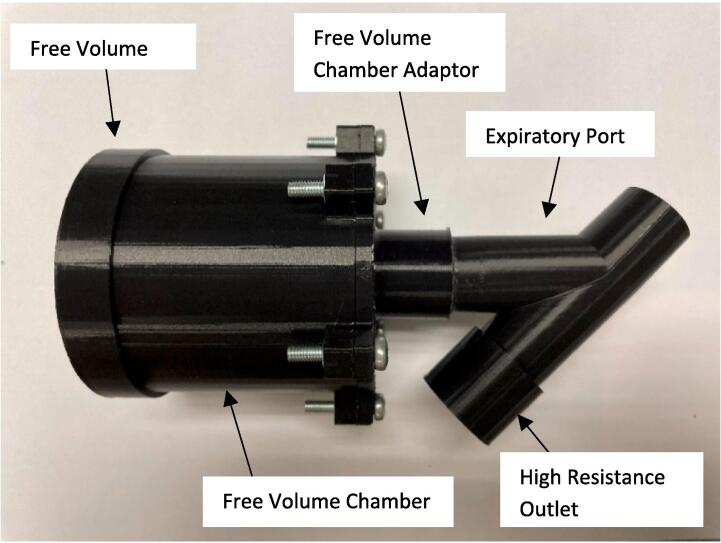

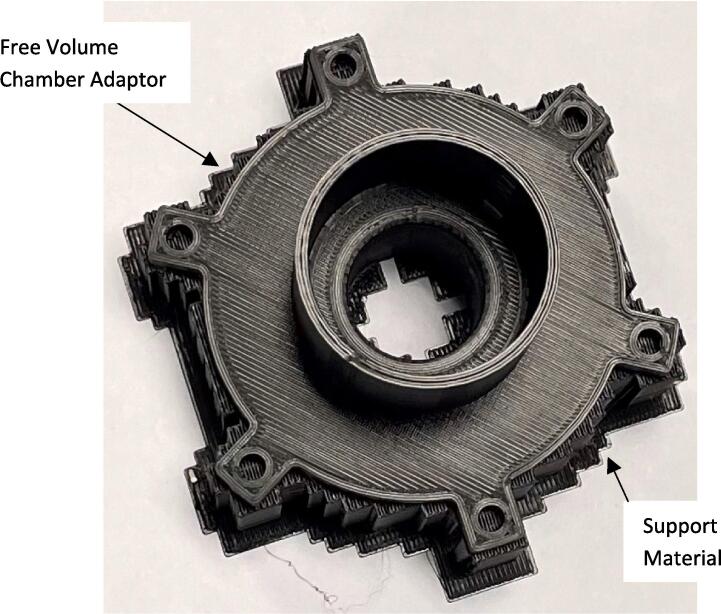

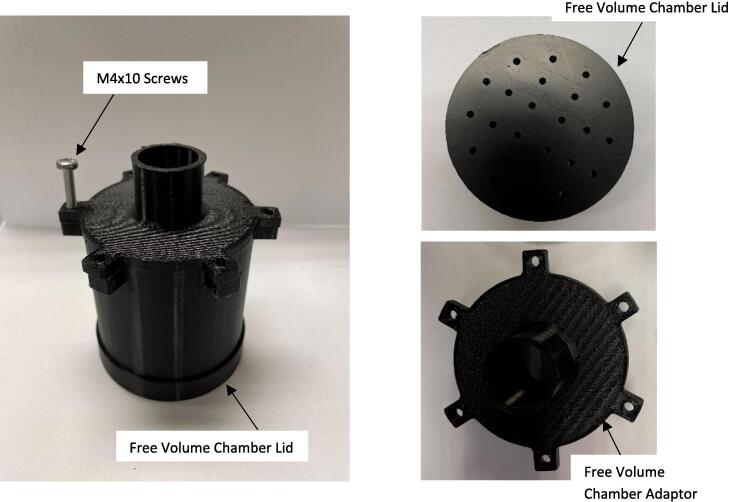

The expiratory port splitter, free volume chamber adaptor, free volume chamber, free volume lid, and high resistance outlet, Fig. 1, were 3D printed with 1.75 mm PLA using a Prusa mini 3D printer (Prusa Mini+, Prusa Research, Prague, Czech Republic). The 3D printer settings were set at 0.10 mm detail with 40 % infill. The only component printed with support was the free volume chamber adaptor, it was printed with supports on the base plate, Fig. 2. The remaining components were 3D printed without supports.

Fig. 1.

COPD simulator assembly.

Fig. 2.

Free volume chamber adaptor 3D printed with supports.

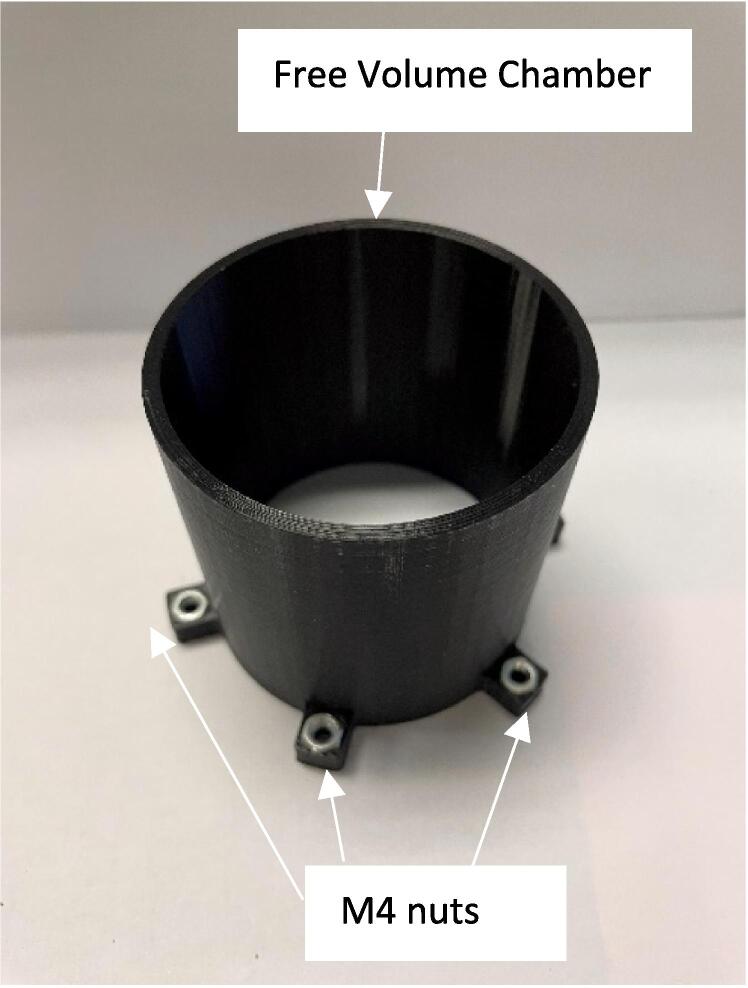

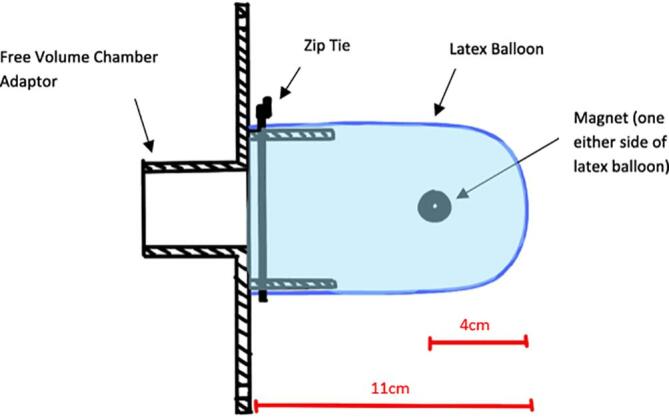

The support material was removed from the free volume chamber adaptor using pliers. The latex balloons were rolled out 11 cm and zip tied (Fig. 3) to the free volume adaptor, the magnets were attached 4 cm from the end to act as a counterweight, Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

Assembly of M4 nuts in Free Volume Chamber.

Fig. 4.

Free volume adaptor and latex balloon assembly.

Attach the free volume adaptor and balloon assembly to the free volume chamber using 6x M4 10 screws and place the lid on the end of the free volume chamber, Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Assembly of free volume chamber.

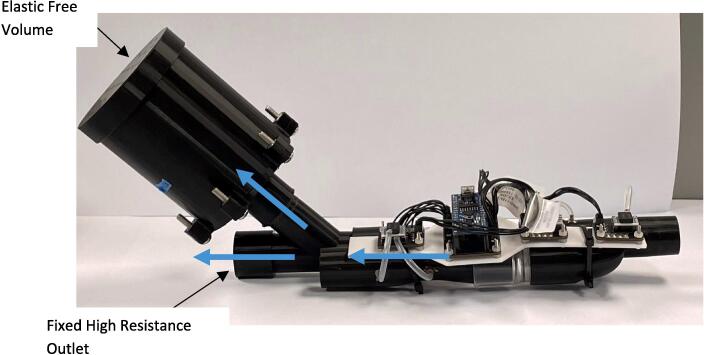

The high resistance outlet and low resistance free volume assembly were press fit onto either side of the expiratory port, Fig. 1, to complete the COPD simulator assembly. Once assembled, the device was used in conjunction with a venturi-based flow sensor with y-split tubing. The device was attached to the expiratory side of the device to collect respiratory data for the validation of pulmonary mechanics models, Fig. 6, Fig. 7.

Fig. 6.

COPD simulator with venturi-based flow sensors.

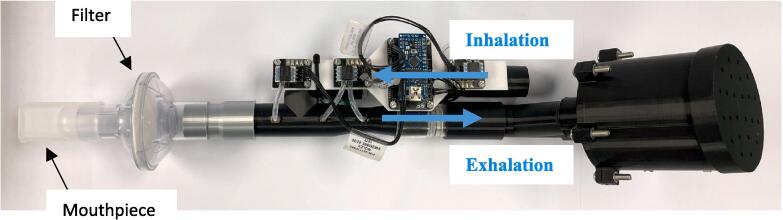

Fig. 7.

COPD simulator assembly with CPAP mouthpiece and filter.

Different disease states, in terms of severity, were simulated by printing various volumes of the free volume chamber. Testing was carried out for each free volume chamber size. Additionally, the size of the resistance hole can be modified to increase or decrease the resistance, and thus the dynamics of simulated gas trapping in the free volume.

Operation instructions

Connect the COPD simulator into the venturi-based flow sensor expiratory port as per Fig. 6. Connect the computer recording the data to the Arduino nano. To the patient end, attach the filter and mouthpiece, Fig. 7.

If using CPAP to record data with added PEEP, attach the CPAP tube to the inhalation side of the venturi-based flow sensor device, Fig. 7.

A mouthpiece and nose clip assembly are preferred with this device as the simulator requires a significant exhalation effort. Due to this effort and high pressure this can cause mask leaks if the CPAP is used with a mask attachment. The nose clip is used in conjunction with the mouthpiece to stop the user beathing out their nose, resulting in unobstructed and uncaptured expiratory flow. Using the MATLAB code, set the time to the desired length and record the data. Breathe normally through the device, additional effort may be required on exhalation. Collect the raw overall pressure and atmospheric differential pressure, inhalation pressure differential and exhalation pressure differential sampled at 100 Hz. This data can then be used to separate each breath and determine the pressure, flow, and volume profile of each breath.

Validation and characterization

The device is characterised by:

-

-

Modular free volume attachments of 200, 250, and 350 mL

-

-

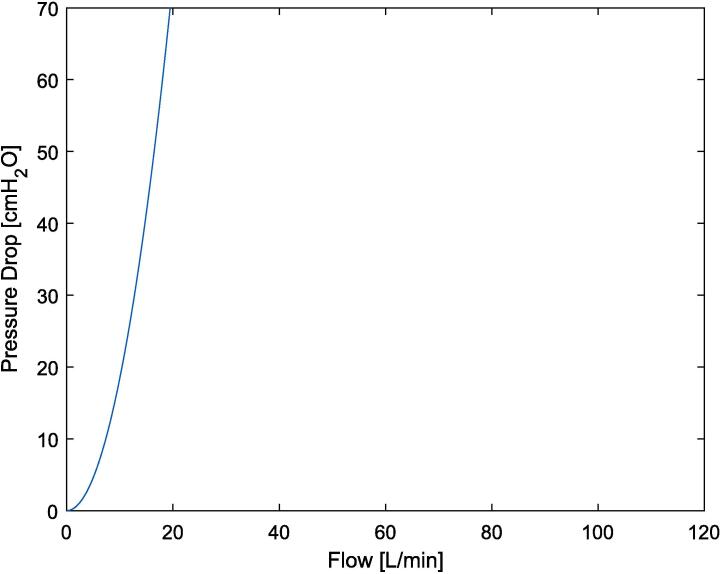

A fixed high resistance outlet – with a parabolic resistance orifice (166 cmH2O at 0.5L/s) (Equation (1), Fig. 8)

Fig. 8.

Resistance curve of fixed parabolic high resistance outlet.

Both of which, are easily customisable by changing the size of the free volume housing, and the size of the hole on the high resistance outlet, respectively.

The data collection system has been validated against a TSI4000 Flow meter (4000 Series Analog and Digital Flow Meter, TSI, Shoreview, MN, USA) [1]. The data collection system used low-cost sensors to measure the pressure differentials of inhalation and exhalation, for further information on the validation of this system refer to [1]. The additional cost of the data collection system was approximately $350 NZD [1] or previous iterations of this data collection system can be used at a lower cost [4], [15].

The fixed parabolic high resistance was characterised using Equation (1), resulting in the plot seen in Fig. 8. The theoretical resistance (Equation (1), Fig. 8) was compared to the pressure and flow curves of known mechanical lung resistors [19].

| (1) |

Equation (1) is derived from Bernoulli using pressure in cmH20 [1], [4], [15]. Where P is the Pressure drop [cmH20], Q the flow [L/min], is density of the air 1.225 kg/m3, A1 and A2 are the area of the Venturi at the inlet and constriction respectively [1], [4], [15].

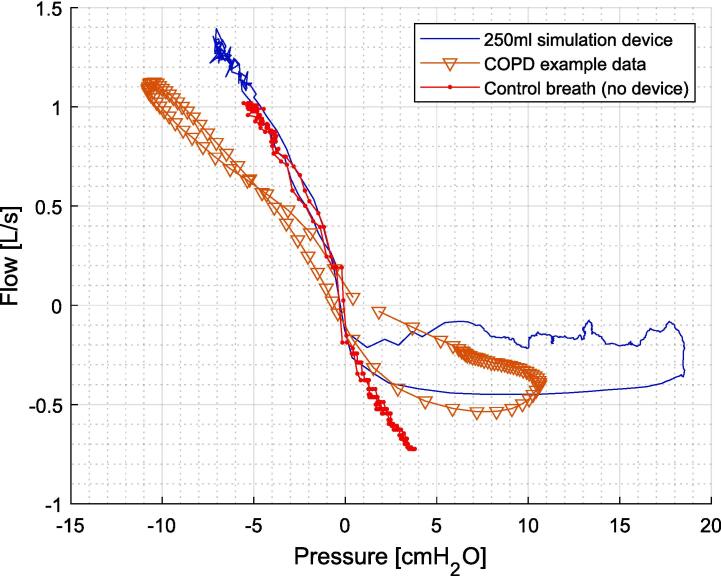

Fig. 9 shows the resulting pressure flow (PQ) curve for one breathing using the 250 mL simulation device compared to the control breath with no device, and real COPD data [20]. Specifically, the expiratory lobe generated by the device in comparison to a normal breath without the device. Where the lobe is generated by the variable resistance free volume before air is solely diverted out the fixed high resistance outlet. In addition, since the data was generated by a healthy subject the control breath on the inspiratory limb matches the blue line when the device is added, where the example COPD data from a clinical study has a different slope, as well as less gas trapping seen in the smaller lobe.

Fig. 9.

Example of PQ plot using COPD simulation device in comparison to no device and PQ loop from real COPD [20], [21].

Ethics statements

Ethics approval for this research was granted by the University of Canterbury Human Ethics Research Committee (Ref: HREC2022/26/LR), with amendments accepted on the 17th of February 2023. Test subjects were voluntarily and given a verbal and written description before starting the trial or signing a consent form.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jaimey A. Clifton: Conceptualization, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. Ella F.S. Guy: Conceptualisation, Software, Validation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Jennifer L. Knopp: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. J. Geoffrey Chase: Conceptualisation, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a University of Canterbury Doctoral Scholarship and the EU H2020 R&I programme (MSCA-RISE-2019 call) under grant agreement #872488 — DCPM.

Biography

Jaimey A. Clifton PhD Candidate at the Centre for Bioengineering in the Mechanical Engineering Department at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand.

References

- 1.Guy E.F.S., Clifton J.A., Knopp J.L., Holder-Pearson L.R., Chase J.G. Respiratory pressure and split flow data collection device with rapid occlusion attachment. HardwareX. 2023/12/01/ 2023,;16:e00489. doi: 10.1016/j.ohx.2023.e00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnard L.T., Zhang J. University of Otago; Dunedin, New Zealand: 2021. The impact of respiratory disease in New Zealand: 2020 update. [Google Scholar]

- 3.M. Tobias, M. Turley, M. Liu, Health loss in New Zealand: A report from the New Zealand burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors study, 2006-2016. Ministry of Health, 2013.

- 4.Guy E.F.S., Geoffrey Chase J., Holder-Pearson L.R. Respiratory bi-directional pressure and flow data collection device with thoracic and abdominal circumferential monitoring. HardwareX. 2022;12:e00354. doi: 10.1016/j.ohx.2022.e00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsestuen J.O., Hargett K.D. Using ventilator graphics to identify patient-ventilator asynchrony. Respiratory Care. 2005;50(2):202–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morton S.E., et al. Optimising mechanical ventilation through model-based methods and automation. Annu. Rev. Control. 2019;48:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lian J.X. “Understanding ventilator waveforms—and how to use them in patient care,” Nursing 2020. Critical Care. 2009;4(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham T., Brochard L.J., Slutsky A.S. Mechanical Ventilation: State of the Art. Mayo Clinic Proceed. 2017;92(9):1382–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isetta V., Navajas D., Montserrat J.M., Farré R. Comparative assessment of several automatic CPAP devices' responses: a bench test study. ERJ Open Research. 2015;1(1):00031–02015. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00031-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris A.H., et al. “Enabling a learning healthcare system with automated computer protocols that produce replicable and personalized clinician actions,” (in eng) J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021;28(6):1330–1344. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.P. Pelosi et al., “Personalized mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome,” (in eng), Crit Care, vol. 25, no. 1, p. 250, Jul 16 2021, doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03686-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Chase J.G., et al. Digital Twins and Automation of Care in the Intensive Care Unit. Cyber–physical–human Systems. 2023:457–489. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chase J.G., et al. Next-generation, personalised, model-based critical care medicine: a state-of-the art review of in silico virtual patient models, methods, and cohorts, and how to validation them. BioMed. Eng. OnLine. 2018/02/20 2018,;17(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12938-018-0455-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerios T., Knopp J.L., Holder-Pearson L., Guy E.F.S., Chase J.G. “An identifiable model of lung mechanics to diagnose and monitor COPD,” (in eng) Comput. Biol. Med. 2023;152 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holder-Pearson L., Chase J.G. Physiologic-range flow and pressure sensor for respiratory systems. HardwareX. 2021;10:e00227. doi: 10.1016/j.ohx.2021.e00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K., et al. “Continuous positive airway pressure improves respiratory mechanics and efficiency of neural drive in stable COPD: an exploratory study,” (in eng) J Thorac Dis. Mar 2020;12(3):626–638. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.12.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanchina M.L., Welicky L.M., Donat W., Lee D., Corrao W., Malhotra A. Impact of CPAP Use and Age on Mortality in Patients with Combined COPD and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: The Overlap Syndrome. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013;09(08):767–772. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang T.-Y., et al. Nocturnal CPAP improves walking capacity in COPD patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Respirat. Res. 2013;14(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R. Chatburn, “Simulation Studies for Device Evaluation,” Respiratory care, vol. 59, pp. e61-6, 04/01 2014, doi: 10.4187/respcare.03047. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Radovanovic D., Pecchiari M., Pirracchio F., Zilianti C., D’Angelo E., Santus P. Plethysmographic Loops: A Window on the Lung Pathophysiology of COPD Patients. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:484. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clifton J.A., et al. Physical Simulation of Obstructive Respiratory Disease. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2023.10.1108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]