Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ultrasound-assisted, PdCo bimetallic, Galvanic replacement reaction, dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole, Dehydrogenation

Highlights

-

•

Highly dispersed Co NPs on a beta zeolite surface were prepared by ESA.

-

•

PdCo bimetallic catalysts with high catalytic dehydrogenation activity were prepared by UGR.

-

•

Synergy of PdCo intermetallic electron transfer and SMSI improved the catalytic performance.

-

•

Pd1Co9/beta exhibited the superior catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation activity.

Abstract

Research and development of high-performance catalysts is a key technology to realize hydrogen energy storage and transportation based on liquid organic hydrogen carriers. Co/beta was prepared using beta zeolite as a carrier via an electrostatic adsorption (ESA)-chemical reduction method, and it was used as the template and reducing agent to prepare bimetallic catalysts via an ultrasonic assisted galvanic replacement process (UGR). The fabricated PdCo/beta were characterized by TEM, XPS, FT-IR, XRD, H2-TPR, and H2-TPD. It was shown that the ultrafine PdCo nanoparticles (NPs) are evenly distributed on the surface of the beta zeolite. There is electron transfer between metal NPs and strong-metal-support-interaction (SMSI), which results in highly efficient catalytic dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole (12H-NEC) dehydrogenation performance of PdCo bimetallic catalysts. The dehydrogenation efficiency reached 100 % in 4 h at 180 °C and 95.3 % in 6 h at 160 °C. The TOF of 146.22 min−1 is 7 times that of Pd/beta. The apparent activation energy of the reaction is 66.6 kJ/mol, which is much lower than that of Pd/beta. Under the action of ultrasonic waves, the galvanic replacement reaction is accelerated, and the intermetal and metal-carrier interactions are enhanced, which improves the catalytic reaction performance.

1. Introduction

Rapid economic development has increased the demand for energy annually, and fossil energy now occupies a high percentage of the energy structure. The emissions such as carbon dioxide and sulfur-containing compounds have increased annually, which contributing to environmental problems such as global warming, haze and acid rain [1], [2], [3]. Exploring new renewable sources of energy and restructuring the energy structure are important measures to promote sustainable development. New energy sources that have been developed and utilized include wind, solar, geothermal and hydrogen energy [4], [5]. Although solar, geothermal and wind energy are abundant and cause little damage to the environment, they are greatly affected by environmental factors, which results in low energy utilization efficiency to affect stable energy supplies. As a renewable, clean and high-efficiency secondary energy carrier, hydrogen has the advantages of abundant resources, high calorific combustion value and nonpollution. Therefore, hydrogen is considered to be the most promising clean energy carrier for the 21st century [6].

Hydrogen is light, easy to diffuse, flammable, and explosive. The low cost, high security, high-efficiency storage and transportation of hydrogen are key factors influencing hydrogen energy on a large scale. Hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) has certainly been studied as one of the significant electrochemical reactions due to its importance in the production of alternative energy sources based on hydrogen with high energy conversion efficiency [7]. Currently, there are a variety of hydrogen storage technologies available [8]. For high-pressure gaseous hydrogen storage, hydrogen gas is compressed and stored in a specific high-pressure vessel to enhance the density of volumetric hydrogen storage. This method is characterized by rapid storage and release of hydrogen and is currently a commonly used hydrogen storage method[9]. When hydrogen is compressed to 70 MPa, it poses a number of safety issues for application[10]. For cryogenic liquid hydrogen storage, hydrogen gas is cooled below −253 °C to form liquid hydrogen, which is stored in insulted tanks[11]. The volumetric hydrogen storage density is 70 kg/m3, but the energy needed in the process of liquefying hydrogen is approximately 30 % of the combustion heat of liquefied hydrogen[12]. Storage and transportation equipment need insulation materials, and expensive storage costs limit large-scale applications. For the physical adsorption of hydrogen, hydrogen is adsorbed on the surface of porous materials by van der Waals forces, which not only requires the material to have a large surface area, but also needs to reduce the adsorption temperature to improve the hydrogen storage capacity. Even at an adsorption temperature was −200 °C, the volumetric hydrogen storage density reached only 30 kg/m3[13]. For metal hydride hydrogen storage, hydrogen reacted with metal to form metal hydrides[14]. There is the highest volumetric hydrogen density compared to the previous three methods. The hydrogen storage process is relatively safe and efficient; however, the lower mass hydrogen density, slower hydrogen release efficiency, and higher hydrogen release temperature limit its large-scale application. Hydrazine can be used as a source of hydrogen, but it's hard to use on a large scale because it's highly toxic[15].

For liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs), hydrogen storage is achieved by the reaction of liquid organic molecules containing unsaturated double bonds with hydrogen[16], [17], [18]. The method realizes hydrogen recycling through reversible reactions of hydrogen with conjugated double bonds during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation processes. The high flash point and chemical stability ensure the safety of hydrogen storage and transportation. Based on the above advantages, LOHCs have great development prospects for future hydrogen storage and transportation, as well as for the application of hydrogen vehicles[19], [20].

LOHCs hydrogen storage systems include dibenzyltoluene (H0-DBT)/perhydrodibenzyltoluene (H18-DBT), toluene (TOL)/methylcyclohexane (MCH), 2-methylindole (2-MID) and octahydro-2-methylindole (8H-2-MID) and, among others[21], [22], [23], [24]. The introduction of heteroatoms into the structure of aromatic hydrocarbons reduces the enthalpy of hydrogenation/dehydrogenation and the dehydrogenation temperature. With a mass hydrogen storage density of 5.8 wt%, NEC has a lower dehydrogenation temperature and recyclable hydrogen storage, which makes NEC/12H-NEC an ideal LOHCs[25], [26]. The NEC/12H-NEC hydrogen storage cycle includes hydrogenation and dehydrogenation reactions. Hydrogenation of NEC is similar to the hydrogenation technology of other aromatic compounds, and the catalysts and catalytic hydrogenation process are very mature. Dehydrogenation of 12H-NEC needs to be completed at atmospheric pressure with a higher reaction rate and lower reaction temperature. The design and development of efficient dehydrogenation catalysts is the key to improving hydrogen storage in NEC[27].

Wang et al. [27] investigated the influence of metal species in loaded catalysts on the dehydrogenation reaction of 12H-NEC. The metal catalyst activity decreased in the order of Pd > Pt > Rh > Ru > Au. Pd-based catalysts are much more effective than other noble metals in terms of dehydrogenation efficiency and product selectivity. To reduce catalyst cost and enhance catalytic dehydrogenation performance, Pd-M bimetallic catalysts have more potential in the field of LOHCs dehydrogenation. The addition of a second metal can adjust the structure of the active sites of Pd to achieve a local atomic arrangement pattern that is more suitable for the adsorption of reactants or for matching the electronic states with the activation orbitals of reactants, thereby improving the catalytic performance and stability of the catalyst during the reaction process. Fang et al. [28] studied the effect of the second metal species on the 12H-NEC dehydrogenation reaction over bimetallic catalysts by adjusting the Pd-M (Co, Ni, or Cu). It was found that the Pd1Co1/Al2O3 exhibited the highest catalytic performance, with a hydrogen release efficiency of 95.3 %, TOF of 230.5 min−1, and NECZ selectivity of 85.4 %. Compared with Pd-M (Cu, Ni) bimetallic catalysts, Pd-Co bimetallic catalysts have smaller metal particle sizes and a greater degree of electron transfer, which results in higher selectivity and catalytic activity. The above results indicate that there is an obvious synergistic effect between the bimetals, which can significantly improve the catalytic performance and selectivity. To further improve the performance of bimetallic catalysts, many researchers have also been exploring a more excellent bimetallic preparation method. Galvanic Replacement Reaction (GRR) is a self-generated oxidation–reduction process that takes advantage of the difference in reduction potentials of metals [29], [30]. Sun et al. [31] prepared a series of Pd-Ag/Al2O3 catalysts via a combination of impregnation and galvanic replacement, and the prepared catalysts were subsequently used to catalyze the hydrodechlorination of 1,2-dichloroethane. The results proved that the catalytic performance was enhanced by Pd modification, which provides a more efficient method for preparing bimetallic catalysts modified with metallic Pd by using the galvanic replacement method. Jung et al. [32] prepared Ni@Pt/C core–shell catalysts by a galvanic replacement reaction (GRR), which showed a significantly enhanced redox reaction compared to that of commercial Pt/C and exhibited excellent durability, with a loss of specific activity of less than 1 % after 10,000 potential cycling tests.

The preparation of template metals is an important factor in the preparation of bimetallic catalysts by the GRR. Wet impregnation has the advantages of simple operation, low production cost and the requirement of a wide range of conditions and is commonly used for the industrial production of catalysts. However, the catalysts prepared by this method have weak metal-carrier mutual effects on the catalyst and uncontrollable adsorption of the metal precursor. The metal particles are prone to migrate and agglomerate to form clusters after reduction, which results in a wider particle size distribution. The metal ion may be anchored to the carrier by electrostatic adsorption (ESA), which results in a greater metal dispersion and smaller metal particle sizes. Ding et al. [33] prepared a series of loaded catalysts that have highly dispersed metal NPs via ESA, which greatly reduced the temperature of the acetylene hydrogenation reaction. Wang et al. [34] anchored the metal Pd2+ to the surface of SBA-15 containing -Si-O- by ESA to generate Pd/SBA-15, which demonstrated outstanding catalytic performance and stability in catalyzing the dehydrogenation of 12H-NEC. The efficient catalytic activity was mainly attributed to the high dispersion of the Pd NPs on the carrier surface. Feng et al. [35] prepared Pd-WU/KIT-6 and Pd-EU/KIT-6 catalysts by impregnation and ionic adsorption methods, respectively, and used them for catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation. It was showed that the dehydrogenation efficiency and TOF values of Pd-EU/KIT6 (97.4 %, 7.08 min−1) were much greater than those of Pd-WU/KIT6 (75.3 %, 2.87 min−1), which further demonstrated that the catalyst prepared by the ESA method could provide greater catalytic activity. Yuranov et al. [36] prepared Pd/HMS and Pd/SBA-15 by the ESA method to increase the metal dispersion and reduce the metal particle size. When the metal loading was increased from 0.25 wt% to 4.4 wt%, the mean particle diameter of the Pd NPs increased by only 2 nm. 2.1 wt% Pd/SBA-15 exhibited good catalytic stability for the methane combustion reaction, indicating that the interaction between the carrier and metal NPs increased due to ESA.

In order to obtain loaded metal catalysts with higher catalytic activity, choosing a suitable catalyst reduction method is one of the important conditions. The ultrasound-assisted method is a relatively novel method for catalyst reduction that is being rapidly developed because of its unique reaction effect. The cavitation phenomenon that occurs during the ultrasonic process may lead to temperature and pressure reaching limits in the liquid. The special energetic surroundings allow a favorable stage for the formation of nanostructures [37], [38], [39]. Grieser et al. [40] prepared Au NPs using ultrasound-assisted fatty alcohol reduction. The results showed that the extent of AuCl4- reduction depended on the activity of the gas-liquid interface in solution, and the particle size of the Au NPs was inversely proportional to the alcohol concentration and alkyl chain length. Ultrasonication in ethanol can prevent excessive growth of Au nuclei, and the particle sizes of the prepared Au NPs are distributed in the range of 9–25 nm. Wu et al. [41] prepared Pd/LDH catalysts via an ultrasound-assisted method and used them for catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation at 180 °C. The hydrogen release reached 4.65 wt% and 5.72 wt% at 1 h and 6 h, respectively, which was better than that of the Pd/LDHs-c catalyst reduced by NaBH4. The hydrogen release efficiency can still reach 98 % after four consecutive cycles. Liu et al. [42] also prepared Ru nanocatalysts using an ultrasound-assisted method. The formed Ru NPs were highly dispersed with small particle sizes. Ru/LDH-CNT were still able to fully convert NEC to 12H-NEC after the 8th cycle. Liu [43] prepared Ni@Pd/MCM41 catalysts by the galvanic replacement method under ultrasound-assisted conditions, and the dehydrogenation efficiency of Pd1-Ni6/MCM41 at 180 °C for 1 h was 97.2 %, while that of Pd1-Ni6/MCM41 for 4 h reached 100 %, which greatly improved the catalytic performance of the catalysts in catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation.

Carriers are important factors that affect loaded metal catalysts. Feng [44] investigated the effect of carriers used for Pd-based catalysts on the catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation reaction. Pd/C was shown to have the best catalytic dehydrogenation activity, which proved that the carrier is an important factor affecting loaded metal catalysts. beta zeolites are widely used as important industrial catalysts for cracking, isomerization, and alkylation because of their large specific surface area, tunable acidity, and low price [45]. In addition, the large number of defect sites and random channels in the beta zeolite skeleton and the abundance of hydroxyl groups on the surface provide favorable conditions for both metal anchoring and ultrasonic environments during catalyst preparation [46], [47].

In this paper, beta zeolite was utilized as a carrier to generate -Si-O- under alkali treatment conditions and (-Si-O-)2Co2+ by ESA and was chemically reduced to obtain highly dispersed Co/beta, which was subsequently used as a templating agent and a reducing agent to generate PdCo bimetallic catalysts (Pd1Con/beta) with Pd2+ by ultrasound-assisted GRR. The crystal structure, functional groups, pore structure, interelemental electronic effects and metal particle size distribution of the prepared PdCo/beta catalysts were characterized via XRD, FT-IR, N2-physical adsorption, XPS, TEM, H2-TPR and H2-TPD. The correlations between the physico-chemical features of the beta zeolite-loaded bimetallic PdCo catalysts and the performance of the catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation reaction were explored and discussed.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Beta zeolite (Si/Al = 80) was purchased from Nankai University Catalyst Plant. PdCl2 (AR) was from Kelley New Materials (Xi'an) Company Ltd.. NaOH (AR), NaBH4 (AR) and Co(NO3)2·6H2O (AR) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Company Ltd.. Dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole(>99.7 %) was synthesized by hydrogenation from N-ethylcarbazole.

2.2. Catalyst preparation

The preparation process of the Pd1Con/beta catalysts is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of Pd1Con/beta catalyst preparation.

Preparation of Co/beta: 0.5 g beta zeolite was dispersed into 20 mL 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution and stirred for 1 h to obtain beta-Si-O-Na+, named beta-Na. Beta-Na was re-dispersed in 30 mL of deionized water after centrifugal washing, keeping the solution pH ∼ 8. According to the theoretical Co loading of 1 wt%-5 wt%, a certain amount of 0.01 mol/L Co(NO3)2 solution was added to the solution, which was then stirred for 1 h and centrifuged. The samples were dried overnight at 60 °C, and the resulting samples were named Co2+/beta. Disperse 0.1 g of Co2+/beta in 30 mL of deionized water. Add 0.01 mol/L NaBH4 solution to the above solution at a ratio of n(Co2+):n(NaBH4) = 1:2 under a N2 atmosphere, while 200 W ultrasound for 15 min. After centrifugal washing and drying to get Co/beta.

Preparation of the PdCo/beta catalysts: First,1 wt% Co/beta was added to 30 mL of deionized water, and 0.01 mol/L H2PdCl4 solution was slowly added dropwise at different Co/Pd molar ratios. With different ultrasound-assisted powers (default 300 W of ultrasound power if not specified) and ultrasonic times (default 3 h if not specified), the galvanic replacement between Co0 and Pd2+ occurred. After centrifugation, washing and drying, the mPd1Con/beta catalyst was obtained (m: mass loading of Co, default 1 wt% if not indicated, n: Co/Pd molar ratio).

The reaction was as follows: Co0 + PdCl22-→Pd0 + Co2++4Cl-.

Preparation of the Pd/beta catalysts: 0.1 g of beta zeolite was dispersed in 20 mL of 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution and stirred for 1 h. The treated beta zeolite was centrifuged and redispersed into 30 mL of deionized water. A defined volume of 0.01 mol/L H2PdCl4 was added, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h. A 0.01 mol/L NaBH4 solution was added dropwise at a n(Pd2+): n(NaBH4) = 1:2. Pd/beta was achieved by drying.

2.3. Catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation performance evaluation

The catalyst performance evaluation process was carried out in a 25 mL glass reactor. The feeding was performed according to n(Pd): n(12H-NEC) = 0.3 %. The reaction temperature was controlled to be 160 ∼ 190 ℃ (180 ℃ was the default if the temperature was not specified), and the samples were withdrawn from the reaction unit at a timed intervals and analyzed using a Shimadzu GC2030 gas chromatograph. The column was SH-Rtx-5, and the temperatures of the column, inlet, and FID detector were 150 ℃, 260 ℃, and 270 ℃, respectively. Hydrogen release at different times of the reaction was calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

where H and W represent the hydrogen release and mass fraction of each component, respectively.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Study on catalyst preparation conditions

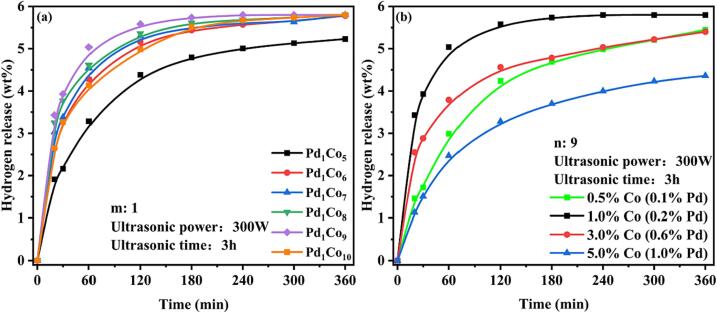

To obtain the optimal fabrication conditions of the catalysts, the influences of the Co/Pd molar ratio, metal Co loading, ultrasonic power and ultrasonic time on catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation were studied, and the experimental results are presented in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Effects of the Co/Pd molar ratio (a) and Co loading (b) on the 12H-NEC dehydrogenation reaction over Pd1Con/beta.

Fig. 3.

Effects of ultrasonic power (a) and ultrasonic time (b) on 12H-NEC dehydrogenation over Pd1Co9/beta.

The Co/Pd molar ratio (n) and Co loading (m) were explored for the preparation of mPd1Con under ultrasonic conditions with an ultrasonic power of 300 W and an ultrasonic time of 3 h. From Fig. 2(a), it can be seen that the catalytic dehydrogenation properties of Pd1Con/beta tend to ascend and then decline with a gradual increase in a molar ratio of n. When n = 6 ∼ 10, hydrogen could be completely released for 6 h. The initial catalytic dehydrogenation performance of Pd1Co9/beta was the highest, hydrogen release reached 5.04 wt% at 1 h and complete hydrogen release was achieved at 4 h. This is due to the fact that the dispersion of Pd NPs increases with the rise of n. As n increases further, the number of active sites on the metal Pd will increase sparse due to the low loading of Pd, which will not be able to contact the reactants sufficiently, thus decreasing the catalytic dehydrogenation reaction performance. As can be observed from Fig. 2(b), the catalytic dehydrogenation performance increases and then decreases with the rise of Co content, and the optimum effect is achieved at 1 wt% Co content. This is attributed to the fact that an increase in the Co load decreases the dispersion of Co NPs, thereby reducing the dispersion of Pd1ConNPs, which lowers the catalytic activity. The low Co loading will result in the metal active sites being sparse and unable to fully contact with the reactants, leading to a decrease in the catalytic dehydrogenation performance.

As can be observed from Fig. 3(a), the catalytic dehydrogenation performance of 12H-NEC over Pd1Co9/beta first increases and then decreases with increasing ultrasonic power. The Pd1Co9/beta catalysts prepared at 100 ∼ 400 W could achieve complete dehydrogenation for 6 h, and the catalysts prepared at 300 W had the highest catalytic dehydrogenation efficiency. This is due to the fact that ultrasonication accelerates the galvanic replacement reaction and favors the formation of PdCo bimetallic nanoparticles. Excessive ultrasonic power may rapidly excite the –OH groups on the beta zeolite surface to generate strongly reducing hydrogen radicals (·H), which directly reduce Pd2+ to Pd [42]. It weakens the interaction between Pd and Co. When the ultrasonic power is reduced, the galvanic replacement reaction may be incomplete, which leads to a decrease in the number of active Pd sites for catalytic dehydrogenation.

As shown in Fig. 3(b), with increasing ultrasonication time, the catalytic dehydrogenation performance of Pd1Co9/beta also increased and then decreased. A short ultrasonication time will cause the galvanic replacement reaction to be incomplete, and the long time will cause the Pd NPs to fall off, leading to weakening of the mutual effect between Pd and Co.

In summary, the optimal preparation conditions for the Pd1Con/beta catalyst were Co loading of 1 wt%, Co/Pd molar ratio of 9, and ultrasonic power and time of 300 W and 3 h, respectively.

3.2. Catalyst characterization

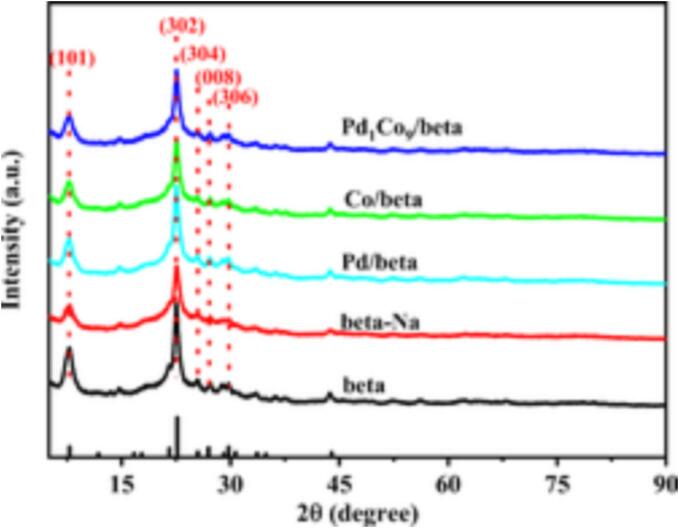

3.2.1. XRD

For investigating the change of crystal structure of carriers, intermediates and catalysts during the catalyst preparation process, XRD analyses of beta, beta-Na, Co/beta and Pd1Co9/beta were carried out, and the results are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

XRD patterns of beta, beta-Na, Pd/beta, Co/beta and Pd1Co9/beta.

As observed in Fig. 4, the XRD patterns of beta-Na prepared from beta zeolite treated with alkali, Co/beta prepared via ESA-chemical reduction, and Pd1Co9/beta catalysts prepared using ultrasound-assisted galvanic replacement all showed typical diffraction peaks corresponding to the *BEA skeleton [48]. Among them, characteristic diffraction peaks appear at 2θ = 7.6°, 22.5°, 25.3°, 26.8°, and 29.6°, which correspond to the (1 0 1) and (3 0 2), (3 0 4), (0 0 8), and (3 0 6) facets of the BEA skeleton, respectively [49], [50]. Although the crystallinity of beta-Na slightly decreased, it still maintained the basic characteristic diffraction peaks of beta zeolite, indicating that the alkali treatment process did not cause damage to the beta skeleton. The crystallinity of the Pd1C9/beta catalyst increased due to the shedding of the heterocrystalline phase caused by the ultrasonic process. The characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 40.1°, 46.7°, 68.1°, 82.1° and 86.6° correspond to the Pd (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 2 0), (3 1 1) and (2 2 2) crystal planes, respectively, and those at 2θ = 30.1° and 59.6° to the Co (2 0 2) and (4 1 1) crystal planes, respectively [51], [52]. The characteristic diffraction peaks of Co and Pd were not observed in the XRD patterns of Co/beta, Pd/beta and Pd1Co9/beta. which was attributed to the high metal dispersion and lower metal loading.

3.2.2. FT-IR

In order to analyze the functional groups of the samples, FT-IR analyses were carried out for beta, beta-Na, Co/beta and Pd1Co9/beta, and the results are presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

FT-IR patterns of beta, beta-Na, Co/beta and Pd1Co9/beta.

It was seen in Fig. 5 that the absorption peaks of beta, beta-Na, Co/beta, and Pd1Co9/beta occurred in the range of 4000–750 cm−1, where the peak at 3659 cm−1 belongs to the stretching vibration of Al-OH [53], those at 3442 cm−1 and 1623 cm−1 to the stretching and bending of H-OH and Si-OH[54], [55], those at 803 cm−1 and 1225 cm−1 to the external symmetric and asymmetric vibrations of Si(Al)-O-Si and that at 1085 cm−1 to the internal symmetric vibrations of Si(Al)-O-Si [56], and that at 960 cm−1 to the symmetric stretching vibrations of the beta zeolite surface Si-OH [57].

From the Al-OH stretching vibrational peak at 3659 cm−1, it was found that there was no change in beta, beta-Na, Co/beta, and Pd1Co9/beta, which suggested that there was not much effect on Al-OH during the preparation process of the catalysts. The symmetric stretching vibrational peak of -Si-OH at 960 cm−1 indicates that the peak intensity of beta-Na is reduced, which is due to the generation of -Si-O- via alkali treatment, which reduced the amount of -Si-OH. The peak intensity at 960 cm−1 for Co/beta is slightly higher than that of beta-Na and lower than that of beta, which may be due to the combination of -Si-O- and H+ on the surface of beta-Na resulting in an increase in the intensity of -Si-OH, but the Co NPs still form coordinated with O, and thus the -Si-OH could not be restored to the initial amount. The peak intensity at 960 cm−1 for Pd1Co9/beta did not change significantly compared to that for Co/beta, which could be attributed to the reason that the Pd NPs were prepared by ultrasound-assisted galvanic replacement instead of reduction by ·H excited via ultrasound. The interaction between Pd and Co can be enhanced by the introduction of Pd formed through UGR.

3.2.3. TEM

The morphology of the bimetallic Pd1Co9/beta catalyst was analyzed using HRTEM, and images is presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

HRTEM image of Pd1Co9/beta.

As can be seen in Fig. 6, Pd NPs and Co NPs were not detected in the 5 nm HRTEM images. This may be due to the high dispersion of the metals and the small particle sizes exceeding the detection limit of HRTEM.

In order to further verify the metal distribution on the surface of the Pd1Co9/beta catalyst, EDS elemental analysis of Pd1Co9/beta was carried out, and the result is shown in Fig. 7. Pd NPs and Co NPs are highly dispersed on the carrier surface as can be seen in Fig. 7(c ∼ g). As can be seen from Fig. 7(h), the actual Co/Pd molar ratio was calculated to be 4.3:1 by EDS spectroscopy which is much less than the theoretical value of 9:1. If all the Pd2+ is reduced by Co during the ultrasound-assisted galvanic replacement reaction, the Co/Pd molar ratio should also be 8:1, which means that PdCo NPs exist as PdCo alloys or as independent PdNPs and CoNPs.

Fig. 7.

EDS elemental mapping images(a ∼ g) and EDS spectrum(h) of Pd1Co9/beta.

3.2.4. XPS

In order to investigate the chemical valence states and electronic effects of the elements in Pd1Co9/beta, Co/beta and Pd/beta, the samples were subjected to XPS analysis, as presented in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

XPS profiles of (a) the full spectrum, (b) Pd1Co9/beta-Pd3d, (c) Pd/beta-Pd3d, (d) Pd1Co9/beta-Co2p, (e) Co/beta-Co2p.

From the full XPS spectra of the Pd1Co9/beta in Fig. 8(a), Co 2p and Pd 3d peaks were observed, demonstrating that the PdCo bimetallic catalysts was successfully prepared. Fig. 8(b, d) shows the XPS profiles of Pd 3d and Co 2p in Pd1Co9/beta catalyst, where 336.3 eV and 341.8 eV belong to 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 of Pd0, 337.8 eV and 343.6 eV belong to 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 of Pd2+, 781.7 eV and 797.3 eV belong to 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 of Co0, and 786.6 eV and 803.0 eV belong to 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 of Co2+ [58], [59], [60]. Fig. 8(c) shows the XPS patterns of Pd 3d in the Pd/beta catalysts, where 335.7 eV and 340.7 eV belong to 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 of Pd0, and 337.0 eV and 343.4 eV belong to 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 of Pd2+, respectively. Fig. 8(e) shows the Co 2p profile of Co/beta, where 781.8 eV and 797.6 eV belong to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 of Co0, respectively, and 786.9 eV and 803.5 eV belong to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 of Co2+ [61], [62]. It can be found that zero-valent Pd0, Co0 and oxidized-valent Pd2+, Co2+ species were found in all XPS patterns, which may be due to the formation of coordination states of Pd NPs and Co NPs with –OH groups on the surface of the beta zeolite in addition to the oxidation of Pd0 and Co0 in the air[63], [64].

It can be seen from Fig. 8 and Table 1 that compared with Co/beta, the electron binding energies of Co0 in the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbitals of Co for Pd1Co9/beta shift in the negative direction by 0.1 eV and 0.3 eV, respectively. Compared with Pd/beta, the 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 orbitals of Pd1Co9/beta are shifted in the positive direction by 0.6 eV and 1.1 eV, respectively. The above results indicated that there was electron transfer between Pd and Co because of the formation of PdCo alloy structure, which was consistent with the EDS results. The increase in the electron binding energy of Pd 3d may be attributed to an enhanced d-band width and a downward shift in the d-band center of Pd 3d, which may be significantly affected by the discrepancy in empty state fractions for both palladium and cobalt [28], [65]. In addition, the movement of the electron cloud from Pd to Co leaves the outer sphere of Pd in slightly electron-poor state, which makes PdCo bimetallic catalyst have much better performance for catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation than Pd/beta.

Table 1.

XPS data for Pd/beta, Co/beta and Pd1Co9/beta.

| Catalysts | Binding Energy(eV) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd 3d5/2 | Pd 3d3/2 | Co 2p3/2 | Co 2p1/2 | |||||

| Pd0 | Pd2+ | Pd0 | Pd2+ | Co0 | Co2+ | Co0 | Co2+ | |

| Pd/beta | 335.7 | 337.0 | 340.7 | 343.4 | – | – | – | – |

| Co/beta | – | – | – | – | 781.8 | 786.9 | 797.6 | 803.5 |

| Pd1Co9/beta | 336.3 | 337.8 | 341.8 | 343.6 | 781.7 | 786.6 | 797.3 | 803.0 |

3.2.5. N2 physical adsorption–desorption

N2 physical adsorption–desorption analyses were carried out to investigate the variation in pore properties, and the results are presented in Fig. 9 and Table S1.

Fig. 9.

N2 -adsorption desorption isotherms (a) and pore size distributions (b) of beta, beta-Na, Co/beta, and Pd1Co9/beta.

As seen from Fig. 9(a), beta zeolite exhibits the characteristics of isotherms I type isotherms, beta-Na and catalysts loaded metals are characterized by both I and IV type isotherms. At relative pressures lower than 0.1, with the isotherms rising rapidly and then converging to a plateau (microporous filling), indicating that all samples have the characteristics of micropore. It means that the textural properties of the carriers were not greatly affected after alkali treatment and sonication, and still mainly maintained microporous characteristics [48], [66]. When the relative pressure was in the range of 0.5–0.99, the hysteresis loop was generated due to the capillary condensation phenomenon, which indicated that intracrystalline mesoporous structure appears in the carrier after alkali treatment and sonication. Compared to beta zeolite, it was shown in Table S1 and Fig. 9(b) show that a pore size distribution in the range of 4 ∼ 12 nm (concentrated at 5 ∼ 6 nm) and the pore volume increased for beta-Na and two catalysts was observed, which may be attributed to the formation of intracrystalline mesoporous after treatment with NaOH solution while destroying part of the micropore channels of the beta zeolite [67].

The BET surface areas of Pd1Co9/beta and Co/beta increased sequentially compared with beta-Na, which could be attributed to the formation of intergranular voids between the metal NPs. The average pore size of Co/beta and Pd1Co9/beta were reduced due to the entry of some metallic NPs into the intergranular or intracrystalline mesoporous of the catalysts during the ultrasound-assisted galvanic replacement process.

3.2.6. H2-TPR and H2-TPD

As presented in Fig. 10(a), Co/beta presented a reduction peak at 528 °C, which was attributed to the reduction peak of CoO interacting with carriers [68]. Pd/beta shows a reduction peak at 510 °C, which belongs to the reduction peak of PdO interacting with the carrier [69]. Pd1Co9/beta shows a reduction peak at 522 °C between the two, which belongs to the co-reduction peak of PdO and CoO interacting with the carrier. The phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that Pd promotes the dissociation of hydrogen molecules to high-activity hydrogen species, such as H+, H-, H3+ and ion pairs, which readily reduce CoOx at relatively low temperatures because of the influence of ultrasonic waves and the enhanced dispersion of CoO on beta zeolites by the formation of Pd NPs. A decrease in the proportion of CoO crystals that tightly interact with the carriers leads to the reduction of CoO at a relatively low temperature.

Fig. 10.

Curves for Pd/beta, Co/beta and Pd1Co9/beta (a) H2-TPR and (b) H2-TPD.

As shown in Table S2, the H2 consumption of Co/beta is much larger than that of Pd/beta, indicating that Co is more easily oxidized. The H2 consumption of Pd1Co9/beta was much lower compared to that of Co/beta, which suggests that Co is encapsulated by Pd via the formation of a Co@Pd structure, and the exposure of Co NPs reduce in agreement with the speculation of the EDS spectral results. The H2 consumption of Pd1Co9/beta is much larger compared to that of Pd/beta, which could be attributed to the smaller particle size and greater dispersion of the Pd NPs, which expose more active Pd sites.

Fig. 10(b) shows the H2-TPD curves for the Pd/beta, Co/beta and Pd1Co9/beta samples. The temperature of desorption is related to the adsorption strength of metal to H2. Since the position of the largest peak usually depends on the total amount of desorbed material, the strength of H2 adsorption by the catalyst was determined by the onset temperature of the peak [70]. The hydrogen desorption temperature is related to the interaction strength between the hydrogen species and the catalyst, and the interaction strength is directly related to the catalytic dehydrogenation performance of the catalyst. Stronger interactions lead to the formation of stable structures between the metal and the reactants, and weaker interactions may result in insufficient metal to activate the reactants, both of which are detrimental to the catalytic dehydrogenation reaction. Compared to Pd1Co9/beta, the lower hydrogen desorption temperature of Pd/beta implies a weaker interaction between Pd and hydrogen, which may explain its lower catalytic activity. The onset temperature of the Pd1Co9/beta catalyst was between those of Pd/beta and Co/beta, indicating that the strength of its interaction with H2 was between these two catalysts. These results indicated that the Pd1Co9/beta catalyst might be more favorable for catalyzing 12H-NEC dehydrogenation. The volume of H2 desorbed is correlated with the area of the H2-TPD curve. As shown in Table S2, the Pd1Co9/beta catalyst had the largest peak area, which was the most H2 desorption peak. This also indicated that the prepared PdCo NPs had a greater dispersion on the surface of the beta zeolite, which was beneficial for the dehydrogenation of 12H-NEC.

3.3. Catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation performance of Pd1Co9/beta

The influence of reaction temperature on the performance of catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation over Pd1Co9/beta was investigated. The comparison with beta zeolite loaded monometallic catalysts was carried out, and the results are presented in Fig. 11 and Table S3.

Fig. 11.

Effect of temperature on the Pd1Co9/beta-catalyzed dehydrogenation for 12H-NEC (a) and comparison of performances between Pd1Co9/beta, Pd/beta and Co/beta at 180 ℃ (b).

It was known from Fig. 11(a) shows that catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation is an endothermic reaction, and an increase in temperature is beneficial for accelerating the 12H-NEC dehydrogenation reaction. As shown in Table S3, the initial dehydrogenation rate rapidly enhanced from 170 °C to 180 °C, with the increase of 1.29 wt% in hydrogen release for 1 h, whereas the increase of 0.46 wt% for 1 h from 180 °C to 190 °C, because the number of active sites was fixed, and the increased number of activated molecules at too high a temperature could only bind to a certain number of active sites for the reaction. The higher reaction temperature not only increases the cost of operating conditions, but also results in energy loss, which is detrimental to energy utilization. Too low a temperature is detrimental to the dehydrogenation of 12H-NEC. When 12H-NEC dehydrogenation reaction was catalyzed by Pd1Co9/beta, hydrogen release reached 5.04 wt% for 1 h, complete dehydrogenation was realized for 4 h with a TOF of 146.22 min−1 under the condition of 180 °C and atmospheric pressure.

As shown in Fig. 11(b), Pd1Co9/beta exhibited the highest catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation performance compared to that of the Pd/beta. The TOF of Pd1Co9/beta was 7 times that of Pd/beta at 20.52 min−1, which may be attributed to the synergy of electron transfer between Pd and Co generated by the alloy structure. As shown in Table S3, hydrogen release of 12H-NEC dehydrogenation catalyzed by Co/Beta was only 0.33 wt% at 6 h, which is a very poor performance of catalytic 12H-NEC dehydrogenation, which may be due to the fact that Co NPs are easily oxidized to CoO during the reaction, hindering their catalytic activity.

In order to investigate the selectivity of the 12H-NEC dehydrogenation reaction catalyzed by the Pd1Co9/beta, Pd/beta and Co/beta catalysts, the product distributions were examined for different time periods, and the results are shown in Fig. 12. During the dehydrogenation reaction over Pd1Co9/beta, the relative concentration of 12H-NEC decreased rapidly, and the relative concentration had dropped to 0 mol/L for 30 min. The relative concentration of NEC increased rapidly, and reached a maximum value at 4 h. The relative concentrations of 8H-NEC and 4H-NEC as intermediate products increased and then decreased rapidly, which indicated that Pd1Co9/beta had very good selectivity for the product NEC during the 12H-NEC dehydrogenation reaction. The lower slopes for intermediate product distribution curves during the dehydrogenation reaction of 12H-NEC over the Pd/beta catalyst were attributed to the low selectivity of Pd/beta catalysts for NEC. The Co/beta catalyst was essentially inactive against 12H-NEC.

Fig. 12.

Distribution of dehydrogenation products over Pd1Co9/beta, Pd/beta and Co/beta (a) 12H-NEC, (b) 8H-NEC, (c) 4H-NEC (d) NEC.

The dehydrogenation of 12H-NEC follows the main reaction kinetics [71]. The kinetic equation for the reaction can be represented according to 12H-NEC consumption as illustrated by equation (2). Integrating equation (2) yields equation (3). Plotting ln(C12H-NEC/C0)-t, the value of the rate constant k was derived from a linear fit. As shown in Fig. 13(a), the fitted lines under the temperature conditions of 160 °C-190 °C all exhibit good linear relationships. As the temperature increases, the |k| value also increases. The linear correlation coefficient was 99.49 % by plotting lnk ∼ 1/RT × 103 as presented by Fig. 13(b). The apparent activation energy of 12H-NEC dehydrogenation was obtained from the Arrhenius equation (lnk = -Ea/RT + lnA). It was obtained that the apparent activation energy of Pd1Co9/beta reached 66.6 kJ/mol, the result much lower than that reported in other literature [72].

| (2) |

| (3) |

where C12H is the concentration of 12H-NEC at time t, C012H is the initial concentration of 12H-NEC, t is the reaction time, and r is the reaction rate.

Fig. 13.

Primary kinetic fitting of 12H-NEC dehydrogenation (a), and 12H-NEC dehydrogenation Arrhenius curve (b) of the Pd1Co9/beta catalyst.

3.4. Study of catalytic stability

The stability of the Pd1Co9/beta catalyst was studied by a cycling test, and the results are presented in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.

Reusability of Pd1Co9/beta (a), TEM images of Pd1Co9/beta-cycled (b), particle size distribution of Pd1Co9/beta- cycled (c), XRD patterns of Pd1Co9/beta- cycled (d).

It can be found for Fig. 14(a) that hydrogen release for 6 h can still reach 5.54 wt% after five times of cycling, which indicates that the Pd1Co9/beta catalyst can still maintain good dehydrogenation efficiency, and this proves that this catalyst has good stability.

As shown in Fig. 14(b, c), the Pd1Co9/beta catalyst has an obvious agglomeration phenomenon and the particle size increases, which may be the reason for the decrease of catalytic activity. As shown in Fig. 14(d), the XRD pattern of the cycled Pd1Co9/beta catalyst still maintains the typical diffraction peaks corresponding to the display of the *BEA skeleton, which indicates that the catalyst carriers were not destroyed after cycling. The characteristic diffraction peaks of metal Pd and Co were not found in the XRD patterns of the post-cycled Pd1Co9/beta catalysts, which may be due to the low metal loading on the surface of beta zeolite.

4. Conclusion

Highly dispersed Co NPs loaded on the surface of beta zeolite were prepared by electrostatic adsorption-chemical reduction method using beta zeolite as a carrier. Pd1Con/beta bimetallic catalysts were prepared by UGR utilizing Co/beta as template and reducing agent. The Pd1Co9/beta catalyst was prepared at a mass loading of 1 % Co, 9:1 M ratio of Co/Pd, ultrasonic power and time of 300 W and 3 h respectively exhibited outstanding catalytic activity of 12H-NEC dehydrogenation. The dehydrogenation efficiency of Pd1Co9/beta reached 100 % in 4 h at 180 °C with a TOF of 146.22 min−1. The dehydrogenation efficiency reached 95.3 % at 160 °C for 6 h with a TOF of 49.47 min−1. The apparent activation energy of the reaction was 66 kJ/mol, which was much lower than that of the Pd/beta. The 6 h dehydrogenation efficiency was able to reach 95.4 % after five cycles. Ultrasound-assisted conditions promoted intermetallic electron transfer and SMSI. Moreover, higher density of Pd on the surface of PdCo alloy NPs can expose more Pd active sites thus improving the catalytic performance.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhongyuan Wei: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Xuefeng Bai: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. A.L. Maximov: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization. Wei Wu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program (2018YFE0108800) and the Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Academy of Sciences (STYZ2022SH01).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.106793.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sun Q., Miao C., Hanel M., Borthwick A.G.L., Duan Q., Ji D., Li H. Global heat stress on health, wildfires, and agricultural crops under different levels of climate warming. Environ. Int. 2019;128:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Z., Chen J., Su Z., Liu Z., Li Y., Wang J., Wu L., Wei H., Zhang J. Acid rain reduces plant-photosynthesized carbon sequestration and soil microbial network complexity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;873 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang C.-W., Chang C.-C., Liang J.-J. The impacts of air quality and secondary organic aerosols formation on traffic accidents in heavy fog–haze weather. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li P., Lian J., Ma C., Zhang J. Complementarity and development potential assessment of offshore wind and solar resources in China seas. Energ. Conver. Manage. 2023;296 doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2023.117705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Y. Deep geothermal resources in China: Potential, distribution, exploitation, and utilization. Energy Geoscience. 2023;4 doi: 10.1016/j.engeos.2023.100209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan C., An Y., Xu G., Kong W. Study of catalytic hydrogenation of N-ethylcarbazole over ruthenium catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2012;37(17):13092–13096. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.04.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiani E., Azizi S.N., Ghasemi S. PdCu bimetallic nanoparticles decorated on ordered mesoporous silica (SBA-15) /MWCNTs as superior electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:25468–25485. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.05.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang S.J., Zhang Z.Y., Tan Y., Liang K.X., Zhang S.H. Review on the characteristics of existing hydrogen energy storage technologies. Energy Sources Part A. 2023;45:985–1006. doi: 10.1080/15567036.2023.2175938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng C.-X., Wang L., Li R., Wei Z.-X., Zhou W.-W. Fatigue test of carbon epoxy composite high pressure hydrogen storage vessel under hydrogen environment. J. Zheijang Univ. Sci. A. 2014;14:393–400. doi: 10.1631/jzus.A1200297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou Y.-Q., von Wolff N., Anaby A., Xie Y., Milstein D. Ethylene glycol as an efficient and reversible liquid-organic hydrogen carrier, Nature. Catalysis. 2019;2:415–422. doi: 10.1038/s41929-019-0265-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Usman M.R. Hydrogen storage methods: Review and current status. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022;167 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2022.112743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modisha P.M., Ouma C.N.M., Garidzirai R., Wasserscheid P., Bessarabov D. The Prospect of Hydrogen Storage Using Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers. Energy Fuel. 2019;33:2778–2796. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b00296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nijkamp M.G., Raaymakers J.E.M.J., van Dillen A.J., de Jong K.P. Hydrogen storage using physisorption – materials demands. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2001;72:619–623. doi: 10.1007/s003390100847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makowski P., Thomas A., Kuhn P., Goettmann F. Organic materials for hydrogen storage applications: from physisorption on organic solids to chemisorption in organic molecules. Energ. Environ. Sci. 2009;2 doi: 10.1039/b822279g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiani E., Azizi S.N., Ghasemi S. Superior electrocatalyst based on mesoporous silica nanoparticles/carbon nanotubes modified by platinum-copper bimetallic nanoparticles for amperometric detection of hydrazine. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 2022;47:20087–20102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.04.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg N., Sarkar A., Sundararaju B. Recent developments on methanol as liquid organic hydrogen carrier in transfer hydrogenation reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021;433 doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brückner N., Obesser K., Bösmann A., Teichmann D., Arlt W., Dungs J., Wasserscheid P. Evaluation of Industrially Applied Heat-Transfer Fluids as Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier Systems. ChemSusChem. 2013;7:229–235. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201300426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuo Y., Yang L., Ma X., Ma Z., Gong S., Li P. Carbon nanotubes-supported Pt catalysts for decalin dehydrogenation to release hydrogen: A comparison between nitrogen- and oxygen-surface modification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:930–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.09.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuo L., Cai J., Yang C., Hao C., Fu Y., Shen J. Highly Loaded and Dispersed Cobalt Catalysts for the Hydrogenation of Toluene with Triethylamine. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019;58:19456–19464. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b03851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller K., Stark K., Emel’yanenko V.N., Varfolomeev M.A., Zaitsau D.H., Shoifet E., Schick C., Verevkin S.P., Arlt W. Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers: Thermophysical and Thermochemical Studies of Benzyl- and Dibenzyl-toluene Derivatives. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015;54:7967–7976. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b01840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng J., Zhou F., Ma H., Yuan X., Wang Y., Zhang J. A Review of Catalysts for Methylcyclohexane Dehydrogenation. Top. Catal. 2021;64:509–520. doi: 10.1007/s11244-021-01465-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L., Yang M., Dong Y., Mei P., Cheng H. Hydrogen storage and release from a new promising Liquid Organic Hydrogen Storage Carrier (LOHC): 2-methylindole. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2016;41:16129–16134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.04.240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang C., Feng Z., Bai X. In situ preparation of Pd nanoparticles on N-doped graphitized carbon derived from ZIF-67 by nitrogen glow-discharge plasma for the catalytic dehydrogenation of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole. Fuel. 2021;302 doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim K.C. A review on design strategies for metal hydrides with enhanced reaction thermodynamics for hydrogen storage applications. Int. J. Energy Res. 2018;42:1455–1468. doi: 10.1002/er.3919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong Y., Yang M., Zhu T., Chen X., Cheng G., Ke H., Cheng H. Fast Dehydrogenation Kinetics of Perhydro-N-propylcarbazole over a Supported Pd Catalyst. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018;1:4285–4292. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.8b00914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L., Wang P., Zhang Y., Wu Y., Chen Z., He C. Synthesis, one and two-photon optical properties of two asymmetrical and symmetrical carbazole derivatives containing quinoline ring. J. Mol. Struct. 2013;1051:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2013.07.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B., Chang T.-Y., Jiang Z., Wei J.-J., Zhang Y.-H., Yang S., Fang T. Catalytic dehydrogenation study of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole by noble metal supported on reduced graphene oxide. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2018;43:7317–7325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.02.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong X., Guo S., Jiang Z., Yang B., Fang T. Tuning the alloy degree for Pd-M/Al2O3 (M=Co/ Ni /Cu) bimetallic catalysts to enhance the activity and selectivity of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole dehydrogenation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:33835–33848. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.07.190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakthavatsalam R., Kundu J. A galvanic replacement-based Cu2O self-templating strategy for the synthesis and application of Cu2O–Ag heterostructures and monometallic (Ag) and bimetallic (Au–Ag) hollow mesocages. CrstEngComm. 2017;19:1669–1679. doi: 10.1039/C7CE00110J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cobley C.M., Xia Y. Engineering the properties of metal nanostructures via galvanic replacement reactions. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 2010;70:44–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun J., Han Y., Fu H., Wan H., Xu Z., Zheng S. Selective hydrodechlorination of 1,2-dichloroethane catalyzed by trace Pd decorated Ag/Al2O3 catalysts prepared by galvanic replacement. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;428:703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.09.168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung J.Y., Kim D.-G., Jang I., Kim N.D., Yoo S.J., Kim P. Synthesis of hollow structured PtNi/Pt core/shell and Pt-only nanoparticles via galvanic displacement and selective etching for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022;111:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2022.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.K. Ding1, D.A.C. *, L.Z. , Z.C. , 4, Amitava D. Roy5, , I.N. Ivanov6, D.C. , A general synthesis approach for supported bimetallic nanoparticles via surface inorganometallic chemistry, Science. 362(6414), 560–564. 10.1126/science.aau4414. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Wang Y., Feng Z., Bai X. Ultrafine palladium nanoparticles supported on mesoporous silica: An outstanding catalytic activity for hydrogen production from dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole. Fuel. 2022;315 doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng Z., Bai X. 3D-mesoporous KIT-6 supported highly dispersed Pd nanocatalyst for dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole dehydrogenation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022;335 doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2022.111789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuranov I., Moeckli P., Suvorova E., Buffat P., Kiwi-Minsker L., Renken A. Pd/SiO2 catalysts: synthesis of Pd nanoparticles with the controlled size in mesoporous silicas. J. Molecul. Catal. A: Chem. 2003;192:239–251. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1169(02)00441-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han G., Li Y., Liu Q., Chen Q., Liu H., Kong B. Improved water solubility of myofibrillar proteins by ultrasound combined with glycation: A study of myosin molecular behavior. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;89 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geng J., Jiang L., Zhu J. Crystal formation and growth mechanism of inorganic nanomaterials in sonochemical syntheses, Science China. Chemistry. 2012;55:2292–2310. doi: 10.1007/s11426-012-4732-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X., Shi J., Bai X., Wu W. Ultrasound-excited hydrogen radical from NiFe layered double hydroxide for preparation of ultrafine supported Ru nanocatalysts in hydrogen storage of N-ethylcarbazole. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;81 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.M.A. Rachel A. Caruso, Franz Grieser*, Sonochemical Formation of Gold Sols, Langmuir. 18(21), 7831–7836. 10.1021/la020276f.

- 41.Wu Y., Liu X., Bai X., Wu W. Ultrasonic-assisted preparation of ultrafine Pd nanocatalysts loaded on Cl- intercalated MgAl layered double hydroxides for the catalytic dehydrogenation of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;88 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X., Bai X., Wu W. Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis of Ru supported on LDH-CNT composites as an efficient catalyst for N-ethylcarbazole hydrogenation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;91 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Z., Feng Z., Bai X. Preparation of MCM-41 supported Ni@Pd core-shell nanocatalysts by ultrasound-assisted galvanic replacement and their efficient catalytic dehydrogenation of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects. 2023;676 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.132277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng Z., Chen X., Bai X. Catalytic dehydrogenation of liquid organic hydrogen carrier dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole over palladium catalysts supported on different supports. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;27:36172–36185. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09698-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Q., Wang N., Yu J. Advances in Catalytic Applications of Zeolite-Supported Metal Catalysts. Adv. Mater. 2021;33 doi: 10.1002/adma.202104442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ge L., Qiu M., Zhu Y., Yang S., Li W., Li W., Jiang Z., Chen X. Synergistic catalysis of Ru single-atoms and zeolite boosts high-efficiency hydrogen storage. Appl. Catal. B. 2022;319 doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.121958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.R.B.L. J.B. Higgins , J.L. Schlenker,” A.C. Rohrman, J.D. Wood, G.T. , The framework topology of zeolite beta, Zeolites. 8(6), 446–452. 10.1016/s0144-2449(88)80219-7.

- 48.Huang G., Ji P., Xu H., Jiang J.-G., Chen L., Wu P. Fast synthesis of hierarchical Beta zeolites with uniform nanocrystals from layered silicate precursor. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017;248:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.03.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qie Z., Ji Z., Xiang H., Zhang X., Alhelali A., Lan L., Alhassawi H., Zhao G., Ou X., Fan X. Microwave-assisted post treatment to make hydrophobic zeolite Beta for aromatics adsorption in aqueous systems. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023;320 doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2023.124148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xing X., Shi X., Ruan M., Wei Q., Guan Y., Gao H., Xu S. Sulfonic acid functionalized β zeolite as efficient bifunctional solid acid catalysts for the synthesis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from cellulose. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;242 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Firdous N., Janjua N.K., Wattoo M.H.S. Promoting effect of ruthenium, platinum and palladium on alumina supported cobalt catalysts for ultimate generation of hydrogen from hydrazine. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2020;45:21573–21587. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.05.167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li N., Tang S., Meng X. Reduced Graphene Oxide Supported Bimetallic Cobalt-Palladium Nanoparticles with High Catalytic Activity towards Formic Acid Electro-oxidation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015;31:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2014.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X., Liu Y., Wu Y., Dong S., Qi G., Chen C., Xi S., Luo P., Dai Y., Han Y., Zhou Y., Guo Y., Wang J. Room temperature removal of high-space-velocity formaldehyde boosted by fixing Pt nanoparticles into Beta zeolite framework. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023;458 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sartori G. Catalytic activity of aminopropyl xerogels in the selective synthesis of (E)-nitrostyrenes from nitroalkanes and aromatic aldehydes. J. Catal. 2004;222:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2003.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Izquierdo-Barba I., Colilla M., Manzano M., Vallet-Regí M. In vitro stability of SBA-15 under physiological conditions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010;132:442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2010.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J., Zhu J., Zhang S., Lv T., Feng Z., Wang Y., Meng C. OSDA-free hydrothermal conversion of kenyaite into zeolite beta in the presence of seed crystals. Solid State Sci. 2020;107 doi: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2020.106370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chirra S., Siliveri S., Adepu A.K., Goskula S., Gujjula S.R., Narayanan V. Pd-KIT-6: synthesis of a novel three-dimensional mesoporous catalyst and studies on its enhanced catalytic applications. J. Porous Mater. 2019;26:1667–1677. doi: 10.1007/s10934-019-00763-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun C., Liu X., Bai X. Highly efficient dehydrogenation of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole over Al2O3 supported PdCo bimetallic nanocatalysts prepared by galvanic replacement. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.10.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li X., Wu F., Zhou W., Chen C., Wang J., Li B., Chen H., Fu J. Low-temperature dehydrogenation of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole catalyzed by PdCo bimetallic oxide. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023;273 doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2023.118650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao C., Yan X., Wang G., Jin Y., Du X., Du W., Sun L., Ji C. PdCo bimetallic nano-electrocatalyst as effective air-cathode for aqueous metal-air batteries. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2018;43:5001–5011. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.01.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiang Y., Zhao J., Qin L., Wu B., Tang X., Xu Y. Construction of PdCo catalysts on Ni bowl-like micro/nano array films for efficient methanol and ethanol electrooxidation. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022;924 doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.166483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Deng M., Ma J., Yang C., Cao T., Yao M., Liu F., Chen H., Wang X. Facile construction of a highly dispersed PdCo nanocatalyst supported on NH2-UiO-66-derived N/O co-doped carbon for hydrogen evolution from formic acid. Mater. Today Chem. 2022;24 doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2022.101001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang L., Wan L., Ma Y., Chen Y., Zhou Y., Tang Y., Lu T. Crystalline palladium–cobalt alloy nanoassemblies with enhanced activity and stability for the formic acid oxidation reaction. Appl. Catal. B. 2013;138–139:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.02.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kottayintavida R., Gopalan N.K. Pd modified Ni nanowire as an efficient electro-catalyst for alcohol oxidation reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2020;45:8396–8404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang Z., Gong X., Guo S., Bai Y., Fang T. Engineering PdCu and PdNi bimetallic catalysts with adjustable alloying degree for the dehydrogenation reaction of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:2376–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.10.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liao Y., Meng X., Shi L., Liu N. NH4F modified β zeolite for aniline condensation to diphenylamine and its catalytic mechanism. Catal. Commun. 2023;175 doi: 10.1016/j.catcom.2023.106624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Albayati T.M., Doyle A.M. Encapsulated heterogeneous base catalysts onto SBA-15 nanoporous material as highly active catalysts in the transesterification of sunflower oil to biodiesel. J. Nanopart. Res. 2015;17 doi: 10.1007/s11051-015-2924-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Profeti L.P.R., Ticianelli E.A., Assaf E.M. Production of hydrogen by ethanol steam reforming on Co/Al2O3 catalysts: effect of addition of small quantities of noble metals. J. Power Sources. 2008;175:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.09.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jin Q., He Y., Miao M., Guan C., Du Y., Feng J., Li D. Highly selective and stable PdNi catalyst derived from layered double hydroxides for partial hydrogenation of acetylene. Appl. Catal. A. 2015;500:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2015.04.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim T.W., Chun H.-J., Jo Y., Kim D., Ko H., Kim S.H., Kim S.K., Suh Y.-W. Electronic vs. Geometric effects of Al2O3-supported Ru species on the adsorption of H2 and substrate for aromatic LOHC hydrogenation. J. Catal. 2023;428 doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2023.115178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sotoodeh F., Zhao L., Smith K.J. Kinetics of H2 recovery from dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole over a supported Pd catalyst. Appl. Catal. A. 2009;362:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2009.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sotoodeh F., Smith K.J. Kinetics of Hydrogen Uptake and Release from Heteroaromatic Compounds for Hydrogen Storage. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010;49:1018–1026. doi: 10.1021/ie9007002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.