SUMMARY

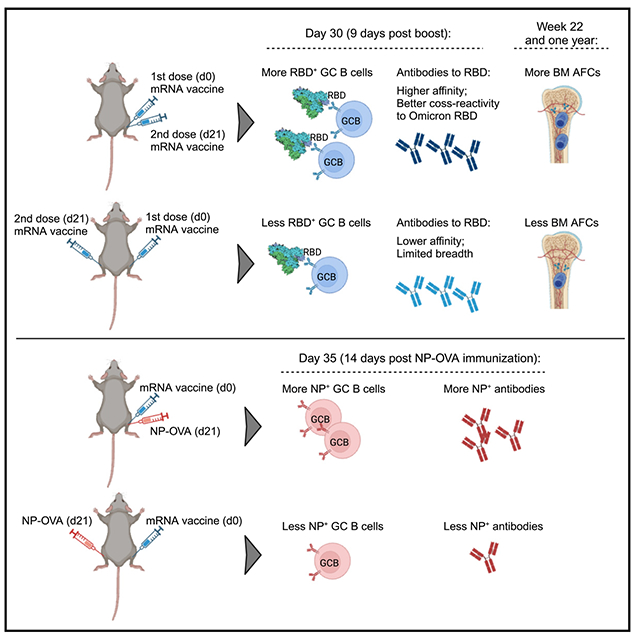

mRNA vaccines have proven to be pivotal in the fight against COVID-19. A recommended booster, given 3 to 4 weeks post the initial vaccination, can substantially amplify protective antibody levels. Here, we show that, compared to contralateral boost, ipsilateral boost of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine induces more germinal center B cells (GCBCs) specific to the receptor binding domain (RBD) and generates more bone marrow plasma cells. Ipsilateral boost can more rapidly generate high-affinity RBD-specific antibodies with improved cross-reactivity to the Omicron variant. Mechanistically, the ipsilateral boost promotes the positive selection and plasma cell differentiation of pre-existing GCBCs from the prior vaccination, associated with the expansion of T follicular helper cells. Furthermore, we show that ipsilateral immunization with an unrelated antigen after a prior mRNA vaccination enhances the germinal center and antibody responses to the new antigen compared to contralateral immunization. These findings propose feasible approaches to optimize vaccine effectiveness.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines require a prime-boost approach to stimulate robust levels of protective antibodies. Jiang et al. demonstrate that receiving the booster shot or a different vaccine on the same side following a prior mRNA vaccination may result in more optimal B cell and antibody responses.

INTRODUCTION

Generation of high-affinity antibodies and long-lived humoral memory is central to the adaptive immunity induced by vaccination. High-affinity antibody production and the development of humoral memory compartments are largely dependent on the germinal center (GC) reaction.1,2 SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines have been used by billions of people worldwide and have saved countless lives. Compared to other vaccines, antigens from mRNA vaccines persist for a long period of time in the draining lymph nodes (dLNs),3 which is associated with robust and persistent GC responses in both humans and animal models, even with a single dose of vaccination.4–9 However, a second dose, recommended to be administered 3–4 weeks following the primary immunization, is required to generate high levels of protective antibodies.7,10 Despite high initial antibody titers upon two doses of vaccination, the antibodies induced by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines wane significantly over time in many individuals, compromising the protective efficacy.11–14 The factors affecting mRNA vaccine efficacy and longevity of antibody responses are not fully understood.

The current guidelines do not offer specific recommendations regarding the preferred side for administering a booster, as it is assumed that both contralateral and ipsilateral boosters result in similar levels of efficacy. Previous research using protein antigens showed that ipsilateral boost at a memory time point can more efficiently recall memory B cells (MBCs) to generate higher affinity GC B cells (GCBCs) compared to contralateral boost.15 One major difference for mRNA vaccines compared to traditional vaccines using protein antigens or inactivated viruses is the persistence of GCs induced by mRNA vaccines.4–9,16 As a result, the second dose of mRNA vaccine is administered while the previous immunization-induced GC reaction is still active, and the immunological memory has not yet fully developed. Consequently, the microenvironment in the dLNs to the booster vaccination may differ significantly between ipsilateral and contralateral boosting strategies. In a recent human study that compared ipsilateral and contralateral boosting strategies of mRNA vaccine, it was found that ipsilateral boost resulted in higher levels of neutralizing antibodies at an early time point compared to contralateral boost, despite no significant difference in total spike antibody titers.17 However, the underlying mechanism, particularly how the boosting side may impact the GC and plasma cell responses, remains unknown. Moreover, mRNA vaccines generate GC responses that can last for months, prompting the question of whether a prior mRNA vaccination will affect the response to subsequent vaccination with an unrelated antigen if administered on the same arm, thereby impacting the vaccine’s efficacy.

To examine how the side of immunization impacts immune responses, we employed animal models that were initially primed with a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. We then evaluated the immune responses to subsequent homologous and irrelevant antigen immunizations administered either to the same limb or the contralateral limb to the initial priming. Our results revealed a significant difference in the GC and antibody responses between ipsilateral and contralateral immunization, with superior humoral responses generated through ipsilateral immunization. These findings indicate that pre-existing GCs and lymph node microenvironment may have a significant impact on the subsequent B cell responses, emphasizing the importance of optimizing vaccination strategies to improve vaccine efficacy.

RESULTS

Ipsilateral and contralateral boost of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine impact the GC response

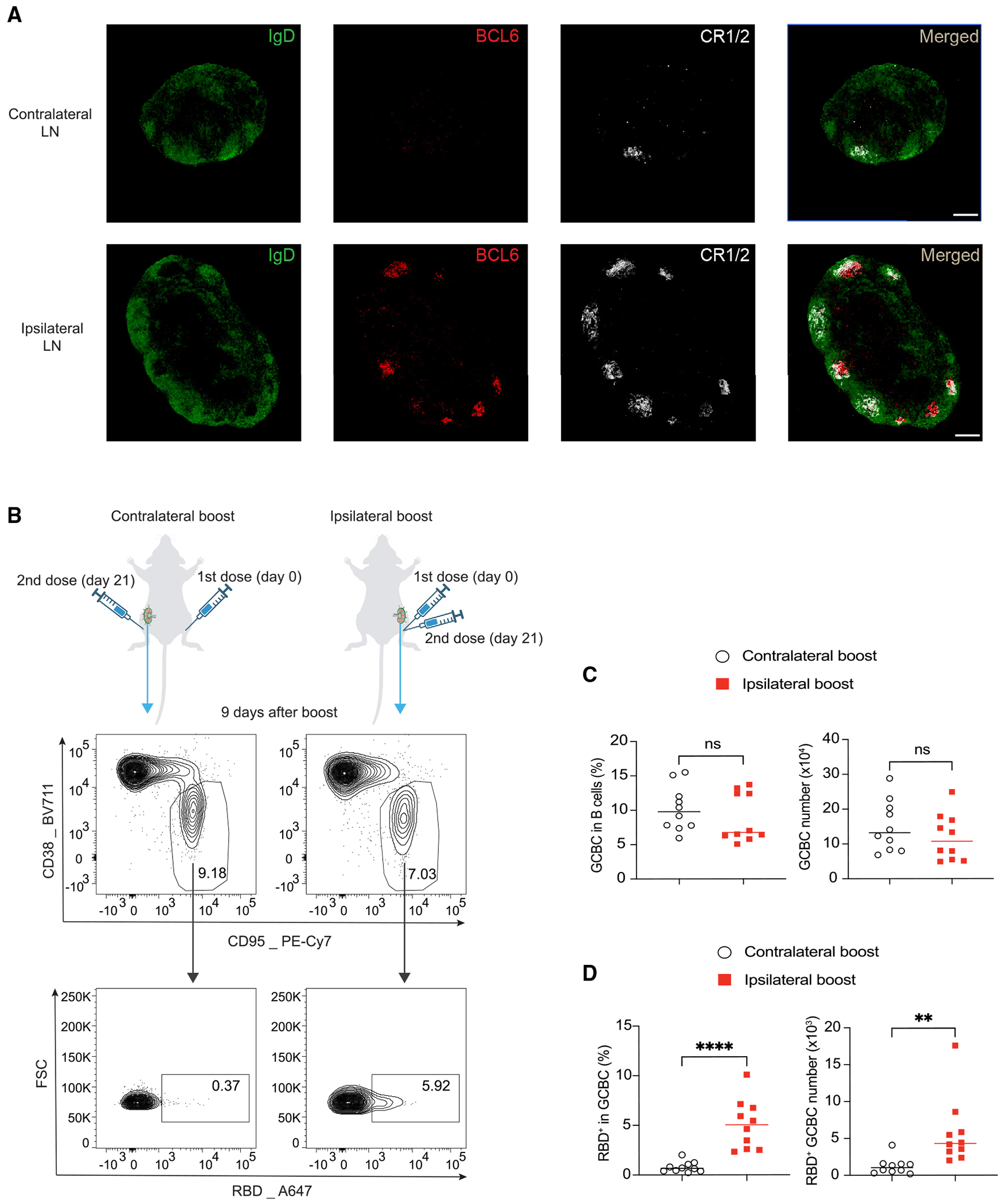

Previous studies have shown that a single dose of mRNA vaccination can result in persistent GC response,4,6–8 suggesting the presence of different microenvironments in ipsilateral LNs compared to contralateral LNs at the time of the booster immunization. To validate this, we conducted immunofluorescence staining and compared the ipsilateral LNs with the contralateral LNs 3 weeks following a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. As expected, the dLNs were larger in size and had a robust ongoing GC response to the vaccination that was largely absent in the contralateral LNs (Figure 1A). Strikingly, the follicular dendritic cell (FDC) network was also highly expanded in the dLNs compared to the contralateral LNs (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Ipsilateral boost of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine induces more RBD-specific GCBCs.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining of ipsilateral dLNs and contralateral LNs 3 weeks after a single dose of mRNA vaccine immunization. Shown are popliteal LNs. Scale bar represents 200 μM. n = 3 from two independent experiments.

(B–D) Mice were vaccinated with 0.2 μg SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine and boosted with the same dose of mRNA vaccine 21 days later in the same limb (ipsilateral boost) or the opposite limb (contralateral boost). 9 days after booster vaccination, total GCBCs and SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific GCBCs in the dLNs to the booster were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry plots (B) and statistical analysis (C and D) are shown. n = 10 from three independent experiments. Each dot represents one mouse, with lines depicting the median. Data were analyzed by unpaired t test. **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001; ns: not significant.

We then investigated whether the different microenvironment in the dLNs between ipsilateral and contralateral boost strategies may impact the subsequent GC response. To test this, we intramuscularly (i.m.) immunized the mice with SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine and boosted them 3 weeks later either in the ipsilateral limb or the contralateral limb (Figure 1B). 9 days later, we analyzed the dLNs in response to the booster immunization by flow cytometry for GCBCs (Figures 1B–1D). Using a fluorescently labeled tetramer probe for SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor binding domain (RBD) (Figure S1A), we identified RBD-specific GCBCs, which have the potential to produce neutralizing antibodies, since the RBD epitope is the major neutralizing target by antibodies.18,19 Surprisingly, although the two boosting strategies induced similar frequencies and numbers of total GCBCs in the dLNs to the booster vaccination, ipsilateral boost generated significantly more RBD-specific GCBCs than contralateral boost (Figures 1B–1D). These findings suggest that the boosting side of mRNA vaccine can impact the quality but not the magnitude of GCBC response.

The choice of boosting side of mRNA vaccine impacts the pre-existing GCBCs from the prior vaccination

Due to the durable GC reaction induced by mRNA vaccines and the short time span between the two doses, antigens from ipsilateral boost but not contralateral boost can directly drain to the LNs where GC reaction that originated from the prior mRNA immunization is still in progress (Figure 1A). Based on this, we hypothesized that ipsilateral boost can more robustly activate the pre-existing GCBCs from the prior vaccination. This, in turn, might explain the observed difference in the subsequent GC response. To investigate this, we focused on the immediate impact of booster vaccination on the pre-existing GC reaction through analyzing the ipsilateral dLNs to the primary vaccination 2 and 4 days after boost (Figure 2A). At these early time points, new GCs induced by the booster vaccination had not begun forming yet. Thus, we could accurately gauge any alterations in the pre-existing GC response.

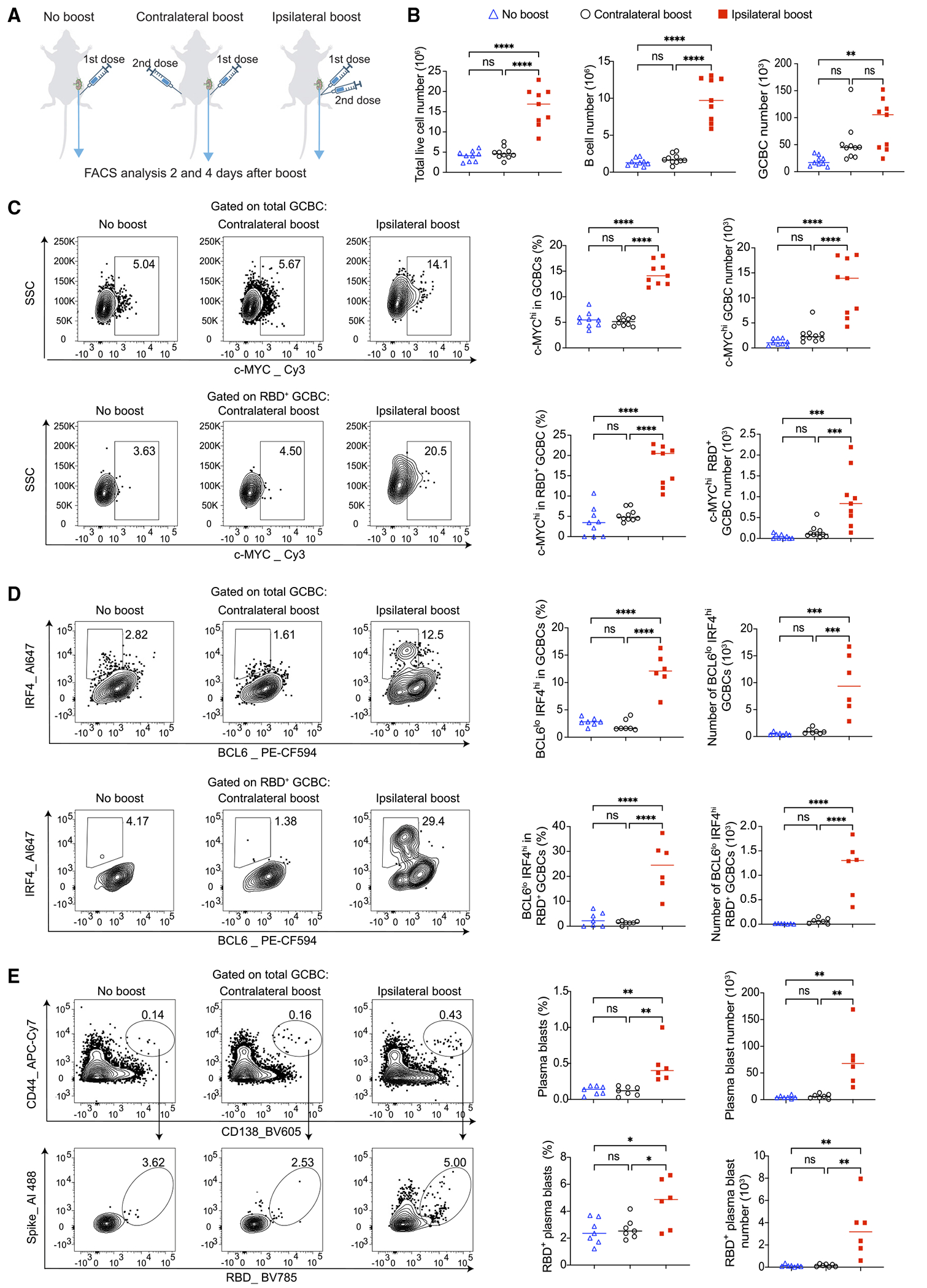

Figure 2. Ipsilateral boost of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine promotes the selection and PC differentiation of pre-existing GCBCs.

(A) Schematic illustration of the experimental design. Mice were primed with 0.2 μg SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine and boosted 3 weeks later either in ipsilateral or contralateral limb. Mice that did not receive booster vaccination were used for comparison. Ipsilateral dLNs to the primary vaccination were analyzed by flow cytometry 4 days post boost.

(B) Groups were compared for the numbers of total live cells, B cells, and GCBCs.

(C) Flow cytometry analysis of c-MYC expression in total and RBD-specific GCBCs.

(D) Flow cytometry analysis of plasma cell precursors (BCL6lo IFR4hi) within total and RBD-specific GCBC populations.

(E) Total plasma blasts and RBD-specific plasma blasts were analyzed by flow cytometry. For (B) and (C), n = 9–10 from three independent experiments. For (D) and (E). n = 6–7 from two independent experiments. Each dot represents one mouse, with lines depicting the median. All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns: not significant. Also see Figure S2 for day 2 analyses.

Through comparing mice that received ipsilateral or contralateral boost with mice that didn’t receive booster vaccination, we found that despite that ipsilateral boost can quickly expand total cells and B cells in the LNs, neither of the boosting strategies caused significant changes in the total number of the pre-existing GCBCs at day 2 (Figures S1B and S2A). At day 4, both boosting strategies increased total numbers of GCBCs in the ipsilateral LNs compared to the no boost group, although this did not reach statistical significance for contralateral boost, and GCBC numbers were not statistically different between the two boosting strategies (Figure 2B). Notably, the frequency of GCBCs within total B cells was lower in mice that received ipsi-lateral boost at day 2 (Figure S2B). This reduction on frequency was attributed to the expansion of non-GC B cells in the ipsilateral LNs of these mice (Figure S2A).

Next, we used c-MYC, a well-established marker for positive selection in the GC,20–22 to evaluate the effects of these boosting strategies on the selection of pre-existing GCBCs. Intriguingly, at both day 2 and 4 post boost, ipsilateral boost substantially enhanced the positive selection of total GCBCs and the GCBC population specific to the RBD (Figures 2C and S2C). In contrast, contralateral boost had no impact on the expression of c-MYC in these pre-existing GCBCs (Figures 2C and S2C). These data suggest that ipsilateral mRNA vaccine boost can indeed significantly enhance the positive selection of pre-existing GCBCs that originated from the prior immunization, likely promoting their involvement in the subsequent GC response.

A subset of GCBCs that have undergone positive selection possess the ability to downregulate BCL6 and upregulate IRF4, a process that drives their differentiation into plasma cells (PCs).23,24 Using intracellular staining of these transcription factors to identify PC precursors (IRF4hi BCL6lo) in the GCBC population, we revealed that ipsilateral boost, but not contralateral boost, led to a significant enhancement in the PC precursor differentiation among total and RBD+ GCBCs at both day 2 and 4 post booster vaccination (Figures 2D and S2D). In line with this observation, we identified elevated numbers of both total and RBD+ plasma blasts in the mice that received ipsilateral boost at day 4 post booster vaccination (Figure 2E).

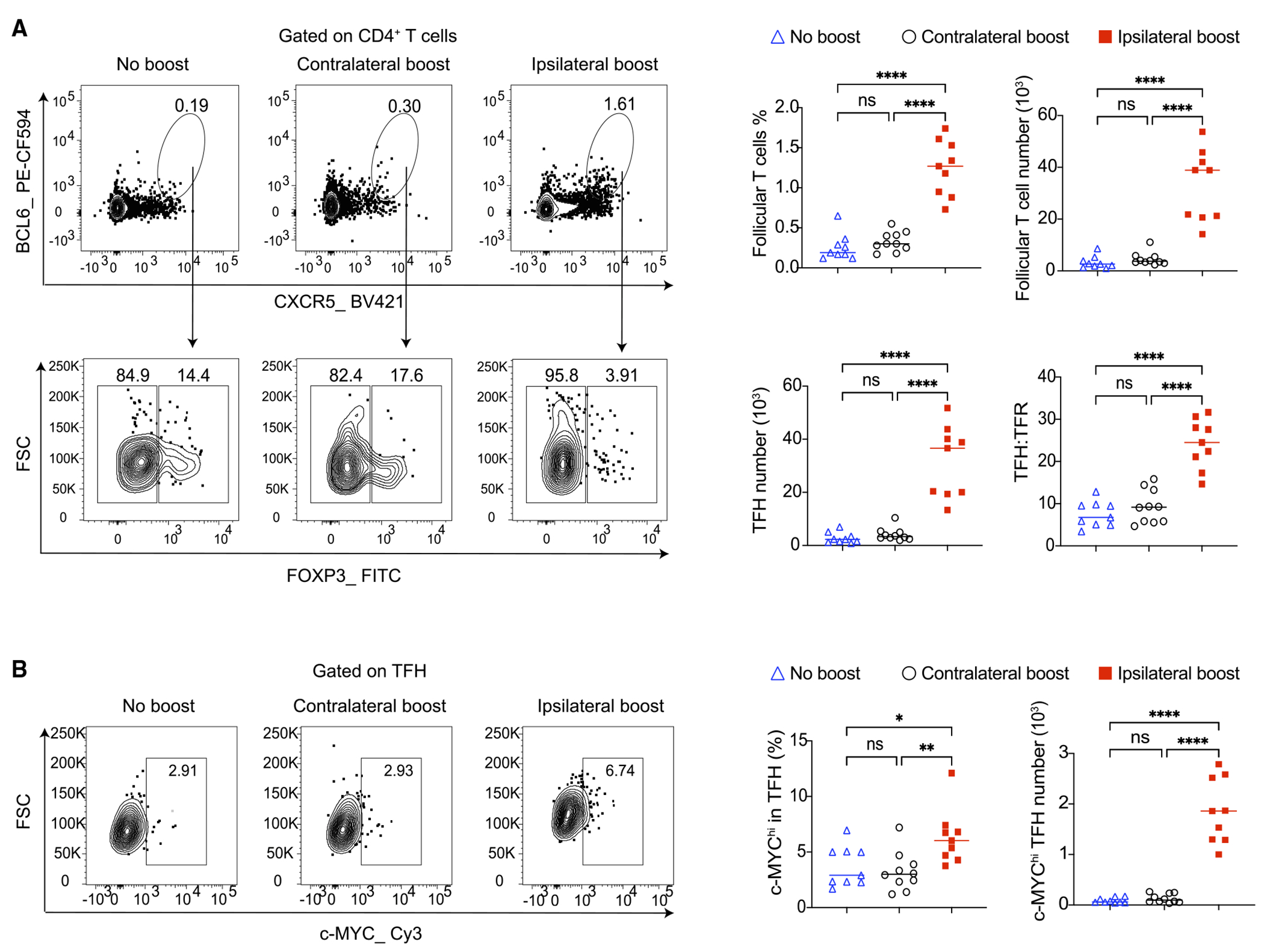

T follicular helper cells (TFHs) are essential for selecting and differentiating GCBCs23,25; on the other hand, FOXP3+ T follicular regulatory cells (TFRs) negatively regulate GC responses.26 The enhanced positive selection and differentiation of pre-existing GCBCs by ipsilateral boost promoted us to investigate these follicular T cell populations. Using established follicular T cell markers and FOXP3 to differentiate between TFH and TFR (Figure 3A), we discovered that ipsilateral boost led to a significant increase in both the frequency and total numbers of follicular T cells 4 days after booster vaccination (Figure 3A). At the same time, ipsilateral boost reduced the TFR frequency, resulting in an elevated ratio of TFH to TFR (Figure 3A). Ipsilateral boost also significantly increased c-MYC expression in TFH (Figure 3B), suggesting enhanced T cell receptor signaling in TFH with ipsilateral boost.27 Hence, ipsilateral boost can increase the accessibility of helper signals for GCBCs by impacting follicular T cell populations.

Figure 3. Ipsilateral boost of mRNA vaccine rapidly expands TFHs and increases the TFH to TFR ratio.

Mice were vaccinated and boosted as in Figure 2A. Ipsilateral dLNs to the primary vaccination were analyzed by flow cytometry 4 days post boost.

(A) Total follicular T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, and TFH and TFR were further separated by their FOXP3 expression.

(B) Analysis of c-MYC expression in TFH. n = 9–10 from three independent experiments. Each dot represents one mouse, with lines depicting the median. All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001; ns: not significant.

These findings provide substantial evidence suggesting a departure from the conventional concept of vaccine boosts that primarily target adaptive memory compartments. Because of the unique characteristics of a durable GC reaction induced by mRNA vaccines, coupled with the short time span between the initial priming and the subsequent booster vaccination, the choice of boosting side (ipsilateral versus contralateral) can distinctly impact pre-existing GC B and T cells. And, this impact has the potential to significantly influence the ensuing GC responses.

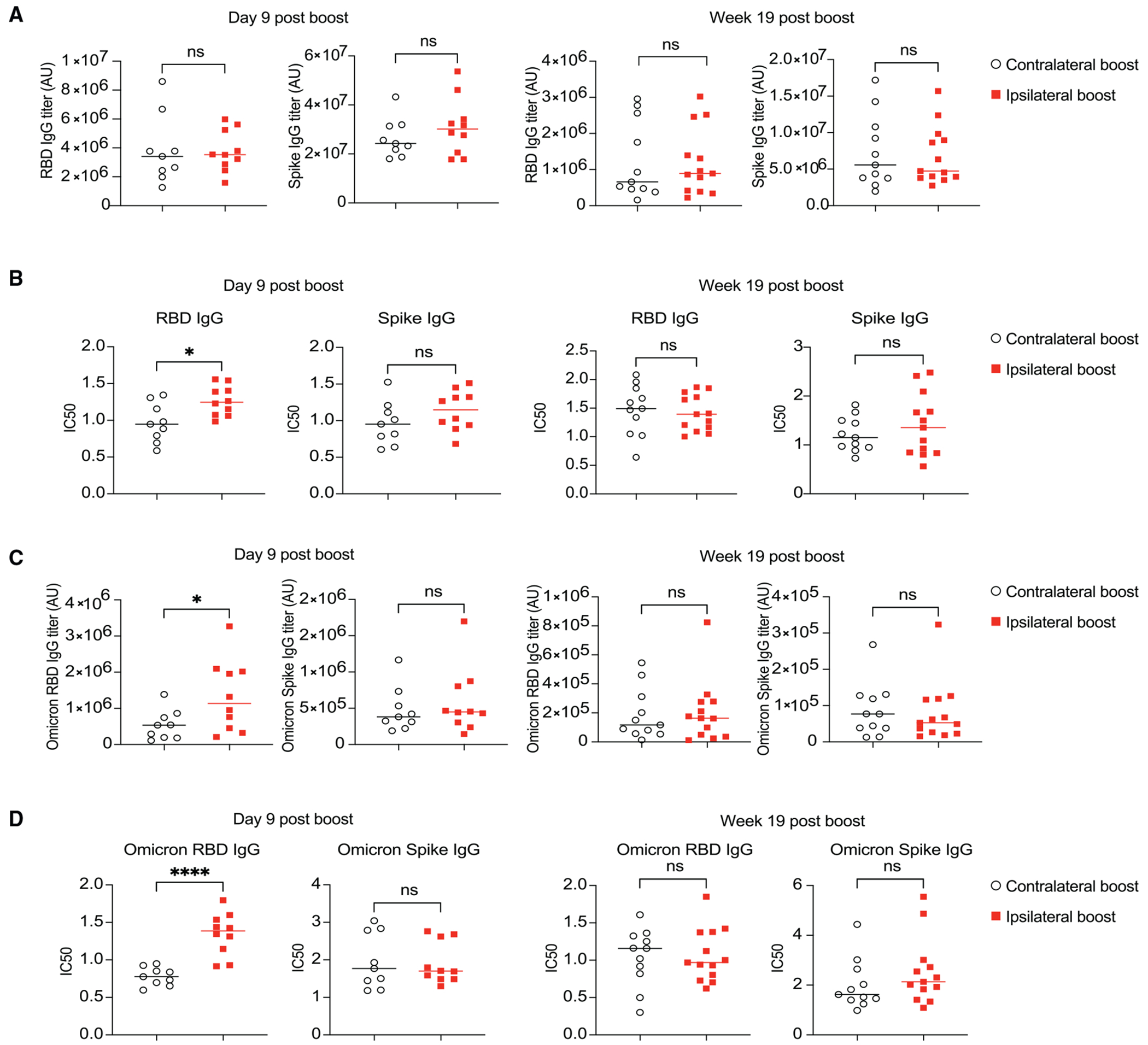

The impact of the boosting strategies on the antibody response

The differences in the GC responses led us to determine whether ipsilateral and contralateral boost of mRNA vaccine may impact the antibody response. We first performed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure the titers of SARS-CoV-2 RBD-and spike-specific antibodies 9 days and 19 weeks post booster vaccination. Interestingly, we found no difference in IgG titers for either RBD or spike protein (Figure 4A). Given that the clonal evolution of GCBCs is instrumental in enhancing the affinity of antibodies, the differences in RBD specificity among GCBCs resulting from the two boosting strategies, along with the capability of ipsilateral boost to promote the differentiation of pre-existing GCBCs into PCs, have motivated us to conduct a more thorough investigation into the antibody affinity. Indeed, the affinity-ELISA assay revealed higher affinity for RBD-specific IgG induced through ipsilateral boost compared to contralateral boost at day 9 post booster immunization (Figure 4B). However, this difference seemed to be transient since this difference in affinity between the antibodies was no longer apparent at 19 weeks following boost immunization (Figure 4B). In contrast to RBD-specific IgG, we found no difference in affinity for spike-specific IgG between the two boosting strategies (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. The boosting side of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine impacts the affinity and breadth of antibody response.

Mice were primed with 0.2 μg SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine and boosted 3 weeks later either in the ipsilateral or the contralateral limb. Serum samples collected 9 days and 19 weeks post booster vaccination were analyzed by ELISA and affinity-ELISA for binding titer and affinity of antibodies, respectively.

(A) SARS-CoV-2 RBD-and spike-specific IgG binding titer measured by ELISA.

(B) Antibody affinity of samples from (A) as measured by IC50 using affinity-ELISA.

(C and D) Samples from (A) were tested for the cross-reactivity against RBD and spike proteins from Omicron viral variant. Binding titer is shown in (C), and affinity is shown in (D). n = 9–10 for day 9 post boost groups from two independent experiments; n = 11–13 for week 19 post boost groups from three independent experiments. Each dot represents one mouse, with lines depicting the median. Data were analyzed by unpaired t test. *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001; ns: not significant.

Next, we assessed the breadth of the antibody response by examining the binding titer and affinity to RBD from the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 that is highly capable of immune evasion. Intriguingly, we observed that compared to contralateral boost, ipsilateral boost of the mRNA vaccine (mRNA encodes the spike protein from the original variant) produced higher titers of antibodies with enhanced affinity against Omicron RBD at the early but not the late time point (Figures 4C and 4D). Again, no difference in Omicron spike-specific IgG was observed (Figures 4C and 4D). This suggests that ipsilateral boost may offer a more rapid and cross-protective neutralizing antibody response compared to contralateral boost.

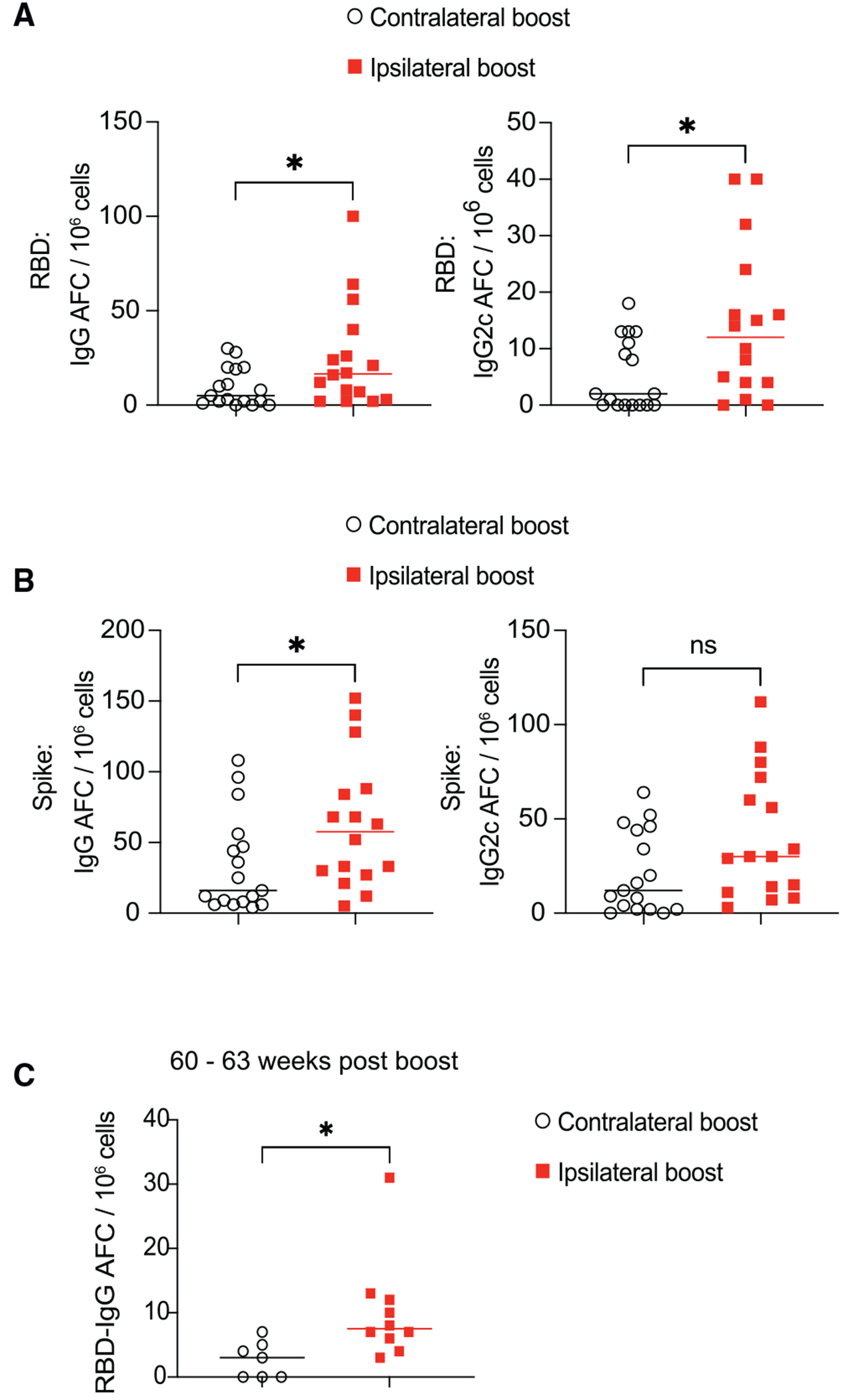

The effects of the boosting strategies of mRNA vaccine on bone marrow plasma cell (BMPC) generation

GC responses give rise to PCs that may migrate to bone marrow. Some BMPCs exhibit an extended lifespan and play a critical role in maintaining the long-term pools of high-affinity circulating antibodies.28,29 To determine whether the side of the booster mRNA vaccination affects BMPC formation, we performed ELISpot assay on bone marrow cells from mice 19 weeks after receiving the mRNA booster vaccination. Consistent with the differences observed in GCBC responses between the two boosting strategies, we found significantly higher numbers of RBD-specific total IgG and IgG2c antibody-forming cells (AFCs) in the bone marrow after ipsilateral boost compared to contralateral boost (Figure 5A). Ipsilateral boost also generated significantly more spike-specific total IgG bone marrow AFCs than contralateral boost (Figure 5B). A similar trend was observed for spike-specific IgG2c antibody AFCs, but the difference did not reach statistical significance between the two groups (Figure 5B). Notably, ipsilateral boost of mRNA vaccine enhanced the generation of BMPCs without affecting total antibody titers at this time point (Figure 4). This implies that mRNA vaccination might generate a substantial quantity of AFCs that do not migrate to the bone marrow, yet they still contribute to the overall production of circulating antibodies.

Figure 5. Ipsilateral boost of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine generates more bone marrow AFCs and long-lived PCs.

Mice were primed with SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine and boosted 3 weeks later either in the ipsilateral or the contralateral limb.

(A and B) 19 weeks post booster immunization, bone marrow cells were analyzed by ELISpot assay for SARS-CoV-2 RBD- and spike-specific antibody-forming cells (AFCs). n = 16–17 from three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by unpaired t test.

(C) 60 to 63 weeks after booster vaccination, bone marrow RBD-specific AFCs were analyzed by ELISpot assay. n = 7–10 from two independent experiments. Each dot represents one mouse, with lines depicting the median. Data were analyzed by unpaired t test. *p < 0.05; ns: not significant.

To further investigate the compartment of long-lived PCs in the bone marrow, we conducted an analysis in mice around 1 year after receiving the booster vaccination. While the numbers of RBD-specific PCs in bone marrow decreased over time, mice that received an ipsilateral boost still had more long-lived PCs compared to mice who received a contralateral boost (Figure 5C).

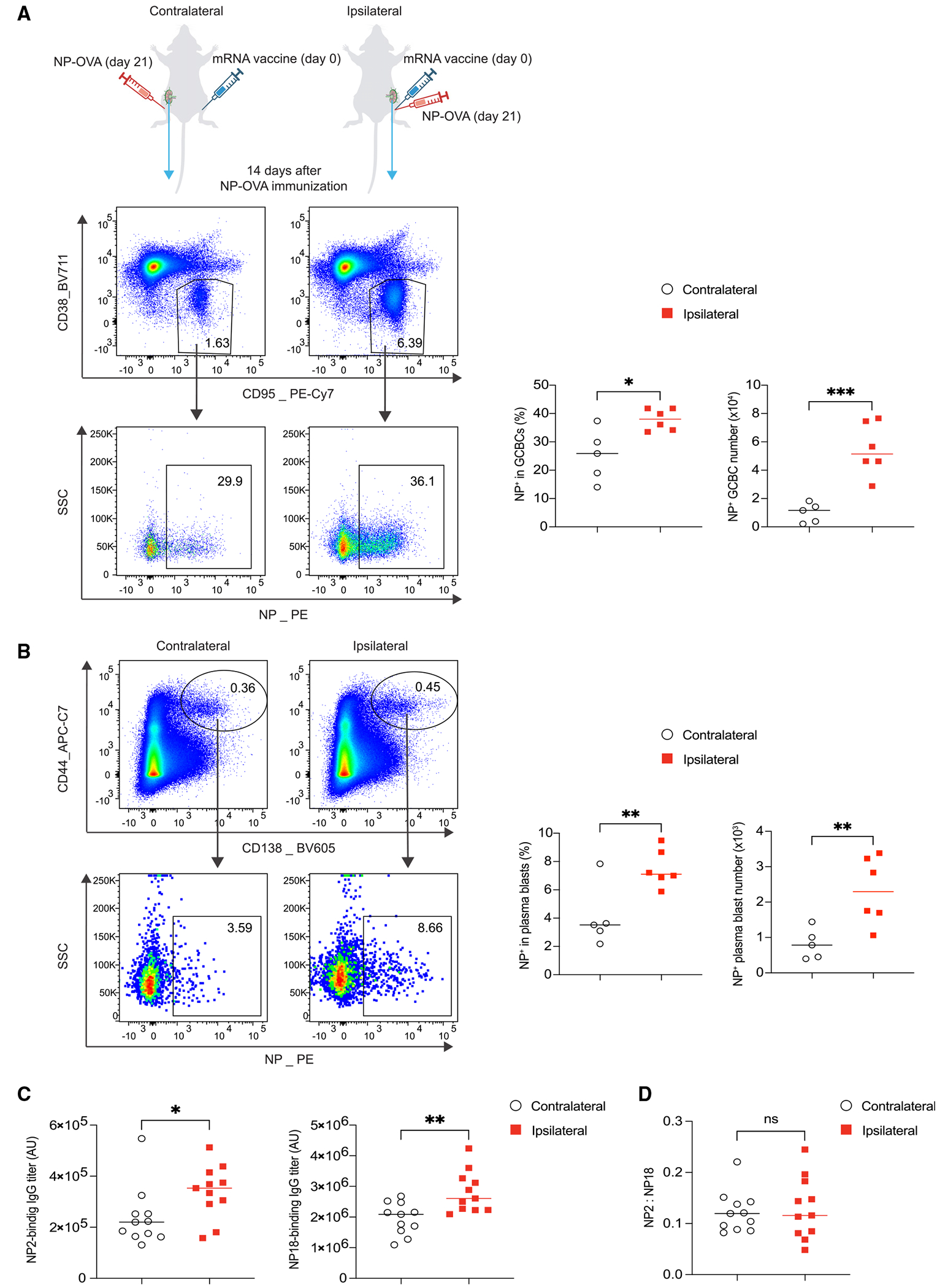

The impact of a prior mRNA vaccination on the subsequent B cell response to an unrelated antigen

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is recommended to receive multiple doses of mRNA vaccines to sustain protective efficacy, especially against emerging viral variants. However, some individuals may need to receive a different type of vaccine after mRNA vaccination. mRNA vaccines can stimulate lasting GC responses that persist for months in the dLNs.4 Moreover, the FDC network in the dLNs can be highly expanded by mRNA vaccination for several weeks (Figure 1A). Given the critical role of immune-stromal interactions in promoting humoral responses,30,31 it is unclear whether the altered microenvironment in the dLNs from a prior mRNA vaccination may affect the B cell response to an unrelated antigen if administered in the same limb. To test this, we i.m. immunized mice with mRNA vaccine, followed by immunization 3 weeks later with alum-adjuvanted 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl conjugated to ovalbumin (NP-OVA) either in the ipsilateral or the contralateral limb (Figure 6A). 2 weeks post NP-OVA immunization, we analyzed NP-specific GCBCs in the dLNs to the NP-OVA immunization. We found that ipsilateral immunization elicited more NP-specific GCBCs in the dLNs compared to contralateral immunization (Figure 6A). Similarly, we observed more NP-specific plasma blasts in the mice with ipsilateral immunization (Figure 6B). In line with these data, we found that ipsilateral NP-OVA immunization after mRNA vaccination induced more high-affinity and total NP-specific IgG antibodies, as measured by NP2- and NP18-BSA binding titers using ELISA assay (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. A prior mRNA vaccination promotes the subsequent B cell responses to an unrelated antigen.

(A and B) Mice were immunized with 0.2 μg SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. 3 weeks later, mice were immunized with 2 μg NP-OVA absorbed in alum in either the contralateral or the ipsilateral limb. Mice were sacrificed and analyzed 2 weeks post NP-OVA immunization. NP-specific GCBCs and plasma blasts in the dLNs were analyzed by flow cytometry. n = 5–6 from two independent experiments and analyzed by unpaired t test.

(C) ELISA plates were coated with NP2- or NP18-BSA for measuring high-affinity and total serum NP-specific IgG, respectively.

(D) Affinity maturation was evaluated by NP2/NP18 ratios. Each dot represents one mouse, with lines depicting the median. n = 11 from four independent experiments and analyzed by unpaired t test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns: not significant.

Even with the increased NP-binding GCBCs induced by ipsilateral boost, there was no change in affinity maturation at this time point, indicated by NP2/NP18 ratios of IgG (Figure 6D). These findings suggest that mRNA vaccination, within a certain period of time, alters the microenvironment in the dLNs, which may promote a subsequent B cell response to an unrelated antigen, indicating potential strategies to enhance vaccine efficacy.

DISCUSSION

In line with the recent human study focusing on the antibody neutralizing activity,17 we show that ipsilateral boost induces more RBD-specific GCBCs and can more rapidly increase the affinity of circulating RBD-specific antibodies, which are known to have neutralization capability. Importantly, taking advantage of animal models, we performed a set of cellular and molecular assessments that yielded crucial mechanistic insights. In sum, our findings suggest that ipsilateral boost of mRNA vaccine can rapidly stimulate the pre-existing GC responses, promoting the selection of GCBCs and TFHs and enhancing the PC differentiation of GCBCs. These are coupled with an enhancement in the generation of RBD+ GCBCs and BMPCs at later time points. Ipsilateral boost also enhances the breadth of antibody response at the early time point. Moreover, we show that ipsilateral immunization with an unrelated antigen following a prior mRNA vaccination can also enhance GC and antibody responses to the new antigen. Notably, there are some differences between our findings and those of the previous study using protein antigens with boosters at memory time points.15 First, we found that the side of mRNA boost can impact the epitope targeting of GCBCs, which was not reported in the previous study.15 Second, we found differences in antibody titers and affinity as well as BMPC formation between the different boosting strategies. The previous study observed no difference in antibody titer and did not examine serum antibody affinity or BMPC formation.15 Additionally, we found that for homologous mRN boosts, ipsilateral immunization may improve the breadth of antibody response. In the previous study, improved breadth was only observed following a heterologous boost.15 Finally, we observed that prior mRNA vaccination may impact the subsequent B cell response to an unrelated antigen, a phenomenon that was not explored in the previous study.15 Some of the different findings may be due to the different experimental designs. For instance, the earlier research primarily focused on the recall response of MBCs.15 In contrast, our study involved administering a booster mRNA vaccination while the prior GC response was still active. And we further demonstrated that ipsilateral boost can substantially impact the pre-existing GCs that originated from the preceding immunization. The different observations between our study and the previous study could also be due to the unique characteristics of mRNA vaccine, especially its ability to constantly produce antigen over longer periods of time3 and to induce more persistent GC response compared to traditional vaccine platforms.4–9,16 Moreover, we cannot rule out that the lipid nanoparticle formulation of mRNA vaccine may introduce additional effects on immune cells.7

Previous studies have shown that sustaining antigen availability through escalating dose immunization or slow delivery using osmotic pumps can enhance GC response, can shift epitope targeting, and can broaden antibody response.32–35 Notably, ipsilateral boost of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine showed similar effects as it can promote RBD+ GCBC response and enhance antibody cross-reactivity against Omicron, a highly mutated viral variant. One common result between these immunization strategies is the extended feeding of antigens to active GCs. Critically, our analyses conducted at 2 and 4 days post the booster mRNA vaccination revealed that refueling pre-existing GC with more antigens can directly promote the positive selection of both GC B and T cells, as measured by the expression of selection marker c-MYC. It is possible that the mechanism underlying the efficacy of escalating dose immunization shares similarities with these effects. This is supported by a prior study on escalating dose immunization, which showed that for same number of injections, extending dosing profile from 7 days to 14 days can markedly improve antibody response.33 Given that GCs typically begin to form around 6–7 days after initial vaccination, extended dosing may benefit from extending the stimulation of ongoing GCs to maximize the effects. Collectively, these studies suggest that prioritizing boosting pre-formed GCs could enhance the overall effectiveness for certain vaccines.

In addition to receiving boosts of the same antigen, individuals may receive immunizations of two unrelated vaccines in close proximity. Our findings indicate that the prior immune responses to mRNA vaccination might create a conducive environment for subsequent GC responses even to an unrelated antigen. Although the exact mechanism is not fully understood, changes in the microenvironment caused by activated immune cells in the dLNs may have bystander effects on subsequent GC reaction, independent of cognate B-T cell interaction. Bystander B cells that constitutively express inducible T cell co-stimulator ligand (ICOSL) may facilitate both the recruitment and maintenance of TFH cells.36,37 IL-21 can also promote CD4+ T cell expansion and GCBC maintenance independent of T-B interaction.38 In addition, recent studies highlight a critical role of stromal-immune cell circuits in supporting humoral responses.30,31 Importantly, we found that the enduring GC response induced by mRNA vaccination is associated with an extensively expanded FDC network in the dLNs. This expansion of stromal cells could potentially offer extra support to B cell responses during subsequent immunizations, even if the antigen is unrelated to the initial immunization. In line with the previous studies, our findings further suggest that the prior immune activation and GC reaction may impact new GC responses to both related and unrelated antigens. Therefore, optimizing the immunization side and schedule can potentially improve vaccine efficacy.

Limitations of the study

Interestingly, despite that ipsilateral boost could generate more BMPCs 19 weeks post booster vaccination, antibody levels were not different between the two boosting strategies. Considering the extended persistence of mRNA vaccine-derived spike protein and mRNA in the dLNs,3 this could be due to the continuous activation of MBCs and the generation of non-bone-marrow-homing AFCs that contribute to the circulating antibody pool. Our study has the limitation in that we are unable to distinguish between antibodies derived from MBC-derived plasma blasts and those from long-lived BMPCs, which requires further investigation.

STAR*METHODS

Detailed methods are provided in the online version of this paper and include the following:

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Wei Luo (wl47@iu.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new reagents.

Data and code availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Mouse models

The study was to investigate whether the sides of immunization following a prior mRNA vaccination can impact the vaccine efficacy. All the results were obtained from at least two independent experiments, with sample numbers indicated in the figure legends. All animals used for comparison within each experiment were age- and sex-matched. Mice of different groups were randomly assigned, and studies were unblinded.

Six to ten weeks old C57/BL6 mice were obtained from the In Vivo Therapeutics Core (IVT) of the Indiana University Simon Cancer Center. Mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions and supervised by the Indiana University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine (Pfizer/BioNTech, BNT162b2) was used as described in the figures. Briefly, the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine was administered at 0.2 μg in 30 μL PBS in the right hindlimb per mouse for the first immunization. For the second immunization, the same dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine, or 2 μg of NP-OVA adjuvanted with Alum (InvivoGen, Cat: vac-alu-50) in 1:1 ratio was administered at either the ipsilateral or contralateral hindlimb 3 weeks later. Mice were analyzed at the indicated time points as described in figures.

METHOD DETAILS

Immunofluorescence

The ipsilateral draining and contralateral non-draining inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes were taken and embedded with OCT (TissueTek) at week 3 post a single dose of mRNA vaccination. The cryostat sections (7μm) were fixed with PBS containing 2% PFA and blocked and permeabilized with buffer (PBS with 1% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 5% mouse and rat serum) prior to staining with the antibody cocktail: Al488 conjugated anti-IgD (BioLegend Cat: 405717), PE conjugated anti-BCL6 (BioLegend Cat: 358504), Al647 conjugated anti-CR1/2 (BioLegend Cat:123424). Images were captured with an DMi8 fluorescent microscope from Lecia company with Leica LAS X software.

Flow cytometry staining and analysis

The draining inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes were taken and processed into single cells with frosted glass slides, filtered by 70 μm strainers, and counted in the cell numbers. Cells were stained with Ghost Dye Violet 510 (Cytek Cat: SKU 13-0870-T100). The cells were then washed and blocked with anti-CD16/32 antibody (S17011E, BioLegend Cat:156604) prior to staining with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against: SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD tetramer (Alexa Fluor 647, BioLegend Cat: 793906, conjugated in our lab), SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD tetramer (Alexa Fluor 785, BioLegend Cat: 793906, conjugated in our lab), SARS-CoV-2 Spike tetramer (Alexa Fluor 605, Sino Biologicals Cat: 40589-V27B-B, conjugated in our lab), SARS-CoV-2 Spike tetramer (Alexa Fluor 488, Sino Biologicals Cat: 40589-V27B-B, conjugated in our lab), B220 (PerCP-Cy5.5, BioLegend Cat: 103236), CD95 (PE-Cy7, BD Pharmingen Cat: 557653), CD38 (BV711, BD OptiBuild Cat: 740697), CD138 (BV605, BioLegend Cat: 142531), CD44 (APC-Cy7, BioLegend Cat: 103028), NP-PE (Biosearch Cat: N-5070). Data were acquired on a BD Fortessa flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo 10.8.1 software.

For intracellular staining: after surface staining with anti-SARS-CoV-2 RBD tetramer (PE and FITC, BioLegend Cat: 793906, conjugated in our lab), B220 (PerCP-Cy5.5, BioLegend Cat: 103236), CD95 (BV786, BD Cat: 740906), CD38 (BV711, BD Cat: 740697), cells were fixed with 2% PFA for 20 mins at room temperature. The cells were washed and permeabilized in Triton-permeabilization buffer (PBS with 2% FCS, 0.02% Azide, 2mM EDTA and 0.1% Triton X-100) for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were then stained with anti-IRF4 (Alexa Fluor 647, BioLegend Cat: 646408), anti-BCL6 (PE-CF594, BD Horizon Cat: 562401) antibodies, c-MYC (Cell Signaling Technology, cat: 18583S, conjugated by secondary antibody), anti-Rabbit 2nd antibody (Cy3 conjugated, BioLegend Cat: 406402). Data were acquired on a BD Fortessa flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo 10.8.1 software.

ELISA and affinity-ELISA assays

SARS-CoV-2 Spike (Cat: 40589-V08B1) protein, SARS-CoV-2 RBD (Cat: 40592-V08H) protein, Omicron Spike (Cat: 40589-V08H26) protein, Omicron RBD (Cat: 40592-V08H121) protein were purchased from Sino Biologicals. NP2-BSA (Cat: N-5050XL-10) and NP18-BSA (Cat: N-5050M-10) proteins were purchased from BioSearch Technologies. Mice were immunized as indicated in figures. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of antibody titers was conducted as described in a previous study.39,40 Briefly, mice were bled at the indicated time points for serological analysis. Serum was obtained by centrifuging whole blood collection in a micro sample tube with serum gel (Sarstedt). High protein binding microplates (Greiner) were coated with 50 μL 2 μg/mL of SARS-CoV-2 RBD or spike protein or 5 μg/mL NP2-BSA or NP18-BSA overnight, then blocked with 5% BSA in PBS-T for 1h. 100μL of diluted serum samples (1:100,000 for SARS-CoV-2 protein test, 1:10,000 for Omicron and NP protein test) were added into wells and incubated at room temperature for 2h. IgG antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG obtained from SouthernBiotech (Cat: 1030-05) and developed using a Thermo Scientific TMB Substrate Kit (Cat: 34021). ELISA data were analyzed using an endpoint analysis. Serial dilution of pooled positive control samples was used to produce an assay sensitivity curve (Prism: Asymmetric Sigmoidal, 5PL, X is log) and biological samples were compared with the curve to assign a titer (AU) relative to the assay’s lower threshold (calculated as the average value of six blank wells plus three times their standard deviation). Groups were then compared by standard statistical testing using Prism statistical analysis software.

The affinity-ELISA assay was conducted as described in a previous study.41 Briefly, based on the above protocol, various concentrations of ammonium thiocyanate (0.15–4 M range) were added into the wells and incubated for 15 min prior to adding the IgG incubation. The plates were developed with TMB substrate solution (Thermo Scientific, Cat: 34021) and quenched with 2N sulfuric acid prior to measurement at 450nm with a microplate reader (BioTek).

ELISPOT assay

The plates (Millipore) were coated with antigens (5 μg/mL SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, or SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein) overnight at 4°C. Then the plates were washed with PBS and blocked using RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, glutamine and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol for 1h. Bone marrow cells were first treated with ACK lysis buffer to deplete red blood cells. Cells were then plated at 0.25 to 1 million cells per well in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, glutamine and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, antigen-specific antibody forming cells were detected by HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1030-05; SouthernBiotech) and IgG2c secondary antibody (1077-05; SouthernBiotech) followed by incubation with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate (AEC Substrate Set; Cat: 551951; BD Biosciences). ELISPOT plates were counted manually with magnification glass and normalized as the number of antibody-secreting cells per 1 million bone marrow cells.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software). For comparing two groups, p-values were determined using Student’s t-tests (two-tailed); for comparing more than two groups, One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey test was applied. Differences between groups were considered significant for p values <0.05 (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgD (clone: 11-26c.2a) | BioLegend | Cat#405717; RRID:AB_10730618 |

| PE anti-human/mouse Bcl-6 (clone: 7D1) | BioLegend | Cat#358504; RRID: AB_2562152 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse CD21/CD35 (clone: 7E9) | BioLegend | Cat#123424 RRID: AB_2629578 |

| TruStain FcX PLUS (anti-mouse CD16/32) (clone: S17011E) | BioLegend | Cat#156604 RRID: AB_2783138 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse/human CD45R/B220 (clone: RA3-6B2) | BioLegend | Cat#103236 RRID: AB_893354 |

| PE-Cy7 Hamster anti-mouse CD95 (clone: Jo2) | BD | Cat#557653 RRID: AB_396768 |

| BV711 Rat anti-mouse CD38 (clone: 90/CD38) | BD | Cat#740697 RRID: AB_2740381 |

| Brilliant Violet 605 anti-mouse CD138 (clone:281-2) | BioLegend | Cat#142531 RRID: AB_2715767 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-mouse/human CD44 (clone:IM7) | BioLegend | Cat#103028 RRID: AB_830785 |

| BV786 Hamster anti-mouse CD95 (clone: Jo2) | BD | Cat#740906 RRID: AB_2740551 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 anti-IRF4 (clone: IRF4.3E4) | BioLegend | Cat#646408 RRID: AB_2564048 |

| PE-CF594 mouse anti-Bcl-6 (clone: K112-91) | BD | Cat#562401 RRID: AB_11152084 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-c-Myc (clone: E5Q6W) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#18583S RRID: AB_2895543 |

| Cyanine3 Donkey anti-rabbit IgG (clone: Poly4064) | BioLegend | Cat#406402 RRID: AB_893532 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP | SouthernBiotech | Cat#1030-05 RRID: AB_2619742 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG2c-HRP | SouthernBiotech | Cat#1077-05 RRID: AB_2794452 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| NP-OVA | Biosearch Technologies | N-5051-10 |

| Alum | InvivoGen | Vac-alu-50 |

| Ghost Dye Violet 510 | Cytek | Cat# SKU 13-0870-T100 |

| Biotinylated Recombinant SARS-CoV2 S protein RBD | BioLegend | Cat#793906 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Spike S1+S2 ECD-AVI&His Recombinant Protein, Biotinylated | SinoBiological | Cat#40589-V27B-B |

| Alexa Fluor 647 Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat#405237 |

| Brilliant Violet 785 Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat#405249 |

| Brilliant Violet 605 Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat#405229 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat#405235 |

| PE Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat#405203 |

| NP-PE (Phycoerythrin) | Biosearch Technologies | Cat#N-5070 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Spike S1+S2 ECD-His Recombinant Protein | SinoBiological | Cat#40589-V08B1 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD-His Recombinant Protein | SinoBiological | Cat#40592-V08H |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron S1+S2 trimer Protein | SinoBiological | Cat#40589-V08H26 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Spike RBD Protein | SinoBiological | Cat#40592-V08H121 |

| NP2-BSA | Biosearch Technologies | Cat#N-5050XL-10 |

| NP18-BSA | Biosearch Technologies | Cat#N-5050M-10 |

| 1-Step TMB ELISA substrate Solutions | ThermoFisher | Cat#34021 |

| Ammonium Thiocyanate | Ward’s science | Cat#470300-264 |

| ELISPOT AEC substrate | BD | Cat#551951 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6 | In Vivo Therapeutics core (IVT) of the Indiana University Simon Cancer Center | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Leica LAS X | Lecia | N/A |

| Flow Jo 10.8.1 | BD | N/A |

| Prism 9 | GraphPad | N/A |

| Other | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine | Pfizer/BioNTech | BNT162b2 |

Highlights.

Ipsilateral boost of mRNA vaccine induces superior GC and plasma cell responses

Ipsilateral boost more rapidly induces high-affinity antibodies with improved breadth

Ipsilateral boost directly activates the ongoing GCs from the prior vaccination

Ipsilateral new antigen immunization post mRNA vaccination improves humoral responses

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the Indiana University Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center (IUSCCC) and Indiana University Cooperative Center of Excellence in Hematology (IU-CCEH) core facilities and LARC staffs for animal colony management. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grant R21AI175824 and startup funds from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Indiana University.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113665.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests.

DECLARATION OF GENERATIVE AI AND AI-ASSISTED TECHNOLOGIES IN THE WRITING PROCESS

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Luo W, and Yin Q (2021). B Cell Response to Vaccination. Immunol. Invest 50, 780–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shlomchik MJ, Luo W, and Weisel F (2019). Linking signaling and selection in the germinal center. Immunol. Rev 288, 49–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Röltgen K, Nielsen SCA, Silva O, Younes SF, Zaslavsky M, Costales C, Yang F, Wirz OF, Solis D, Hoh RA, et al. (2022). Immune imprinting, breadth of variant recognition, and germinal center response in human SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination. Cell 185, 1025–1040.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner JS, O’Halloran JA, Kalaidina E, Kim W, Schmitz AJ, Zhou JQ, Lei T, Thapa M, Chen RE, Case JB, et al. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Nature 596, 109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Naradikian MS, Parkhouse K, Cain DW, Jones L, Moody MA, Verkerke HP, Myles A, Willis E, et al. (2018). Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines induce potent T follicular helper and germinal center B cell responses. J. Exp. Med 215, 1571–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laczkó D, Hogan MJ, Toulmin SA, Hicks P, Lederer K, Gaudette BT, Castarño D, Amanat F, Muramatsu H, Oguin TH 3rd., et al. (2020). A Single Immunization with Nucleoside-Modified mRNA Vaccines Elicits Strong Cellular and Humoral Immune Responses against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice. Immunity 53, 724–732.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li C, Lee A, Grigoryan L, Arunachalam PS, Scott MKD, Trisal M, Wimmers F, Sanyal M, Weidenbacher PA, Feng Y, et al. (2022). Mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity to the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine. Nat. Immunol 23, 543–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lederer K, Castarño D, Gómez Atria D, Oguin TH 3rd, Wang S, Manzoni TB, Muramatsu H, Hogan MJ, Amanat F, Cherubin P, et al. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccines Foster Potent Antigen-Specific Germinal Center Responses Associated with Neutralizing Antibody Generation. Immunity 53, 1281–1295.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mudd PA, Minervina AA, Pogorelyy MV, Turner JS, Kim W, Kalaidina E, Petersen J, Schmitz AJ, Lei T, Haile A, et al. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination elicits a robust and persistent T follicular helper cell response in humans. Cell 185, 603–613.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh EE, Frenck RW Jr., Falsey AR, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Neuzil K, Mulligan MJ, Bailey R, et al. (2020). Safety and Immunogenicity of Two RNA-Based Covid-19 Vaccine Candidates. N. Engl. J. Med 383, 2439–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrotri M, Navaratnam AMD, Nguyen V, Byrne T, Geismar C, Fragaszy E, Beale S, Fong WLE, Patel P, Kovar J, et al. (2021). Spike-antibody waning after second dose of BNT162b2 or ChAdOx1. Lancet 398, 385–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizrahi B, Lotan R, Kalkstein N, Peretz A, Perez G, Ben-Tov A, Chodick G, Gazit S, and Patalon T (2021). Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 Breakthrough Infections to Time-from-vaccine. Nat. Commun 12, 6379. 10.1038/s41467-021-26672-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas SJ, Moreira ED, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Perez JL, Pérez Marc G, Polack FP, Zerbini C, et al. (2021). Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine through 6 Months. New Engl. J. Med 1761–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pouwels KB, Pritchard E, Matthews PC, Stoesser N, Eyre DW, Vihta KD, House T, Hay J, Bell JI, Newton JN, et al. (2021). Effect of Delta variant on viral burden and vaccine effectiveness against new SARS-CoV-2 infections in the UK. Nat. Med 27, 2127–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuraoka M,Yeh CH, Bajic G, Kotaki R, Song S, Windsor I, Harrison SC, and Kelsoe G (2022). Recall of B cell memory depends on relative locations of prime and boost immunization. Sci. Immunol 7, eabn5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner JS, Zhou JQ, Han J, Schmitz AJ, Rizk AA, Alsoussi WB, Lei T, Amor M, McIntire KM, Meade P, et al. (2020). Human germinal centres engage memory and naive B cells after influenza vaccination. Nature 586, 127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziegler L, Klemis V, Schmidt T, Schneitler S, Baum C, Neumann J, Becker SL, Gärtner BC, Sester U, and Sester M (2023). Differences in SARS-CoV-2 specific humoral and cellular immune responses after contralateral and ipsilateral COVID-19 vaccination. EBioMedicine 95, 104743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto D, Park YJ, Beltramello M, Walls AC, Tortorici MA, Bianchi S, Jaconi S, Culap K, Zatta F, De Marco A, et al. (2020). Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature 583, 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiaojie S, Yu L, Lei Y, Guang Y, and Min Q (2020). Neutralizing antibodies targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Stem Cell Res. 50, 102125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo W, Weisel F, and Shlomchik MJ (2018). B Cell Receptor and CD40 Signaling Are Rewired for Synergistic Induction of the c-Myc Transcription Factor in Germinal Center B Cells. Immunity 48, 313–326.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dominguez-Sola D, Victora GD, Ying CY, Phan RT, Saito M, Nussenzweig MC, and Dalla-Favera R (2012). The proto-oncogene MYC is required for selection in the germinal center and cyclic reentry. Nat. Immunol 13, 1083–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calado DP, Sasaki Y, Godinho SA, Pellerin A, Köchert K, Sleckman BP, de Alborán IM, Janz M, Rodig S, and Rajewsky K (2012). The cell-cycle regulator c-Myc is essential for the formation and maintenance of germinal centers. Nat. Immunol 13, 1092–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo W, Conter L, Elsner RA, Smita S, Weisel F, Callahan D, Wu S, Chikina M, and Shlomchik M (2023). IL-21R signal reprogramming cooperates with CD40 and BCR signals to select and differentiate germinal center B cells. Sci. Immunol 8, eadd1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ise W, Fujii K, Shiroguchi K, Ito A, Kometani K, Takeda K, Kawakami E, Yamashita K, Suzuki K, Okada T, and Kurosaki T (2018). T Follicular Helper Cell-Germinal Center B Cell Interaction Strength Regulates Entry into Plasma Cell or Recycling Germinal Center Cell Fate. Immunity 48, 702–715.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, Cui Y, Yao Y, Liu B, Yunis J, Gao X, Wang N, Cañete PF, Tuong ZK, Sun H, et al. (2023). Heparan sulfate regulates IL-21 bioavailability and signal strength that control germinal center B cell selection and differentiation. Sci. Immunol 8, eadd1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miles B, and Connick E (2018). Control of the Germinal Center by Follicular Regulatory T Cells During Infection. Front. Immunol 9, 2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merkenschlager J, Finkin S, Ramos V, Kraft J, Cipolla M, Nowosad CR, Hartweger H, Zhang W, Olinares PDB, Gazumyan A, et al. (2021). Dynamic regulation of T(FH) selection during the germinal centre reaction. Nature 591, 458–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elsner RA, and Shlomchik MJ (2020). Germinal Center and Extrafollicular B Cell Responses in Vaccination, Immunity, and Autoimmunity. Immunity 53, 1136–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, and Slifka MK (2007). Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N. Engl. J. Med 357, 1903–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva-Cayetano A, Fra-Bido S, Robert PA, Innocentin S, Burton AR, Watson EM, Lee JL, Webb LMC, Foster WS, McKenzie RCJ, et al. (2023). Spatial dysregulation of T follicular helper cells impairs vaccine responses in aging. Nat. Immunol 24, 1124–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lütge M, De Martin A, Gil-Cruz C, Perez-Shibayama C, Stanossek Y, Onder L, Cheng HW, Kurz L, Cadosch N, Soneson C, et al. (2023). Conserved stromal-immune cell circuits secure B cell homeostasis and function. Nat. Immunol 24, 1149–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cirelli KM, Carnathan DG, Nogal B, Martin JT, Rodriguez OL, Upadhyay AA, Enemuo CA, Gebru EH, Choe Y, Viviano F, et al. (2019). Slow Delivery Immunization Enhances HIV Neutralizing Antibody and Germinal Center Responses via Modulation of Immunodominance. Cell 177, 1153–1171.e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tam HH, Melo MB, Kang M, Pelet JM, Ruda VM, Foley MH, Hu JK, Kumari S, Crampton J, Baldeon AD, et al. (2016). Sustained antigen availability during germinal center initiation enhances antibody responses to vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E6639–E6648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, Sutton HJ, Cottrell CA, Phung I, Ozorowski G, Sewall LM, Nedellec R, Nakao C, Silva M, Richey ST, et al. (2022). Long-primed germinal centres with enduring affinity maturation and clonal migration. Nature 609, 998–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He WT, Yuan M, Callaghan S, Musharrafieh R, Song G, Silva M, Beutler N, Lee WH, Yong P, Torres JL, et al. (2022). Broadly neutralizing antibodies to SARS-related viruses can be readily induced in rhesus macaques. Sci. Transl. Med 14, eabl9605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan Z, Lin Y, Zhao Y, and Qi H (2019). T(FH) cells in bystander and cognate interactions with B cells. Immunol. Rev 288, 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu H, Li X, Liu D, Li J, Zhang X, Chen X, Hou S, Peng L, Xu C, Liu W, et al. (2013). Follicular T-helper cell recruitment governed by bystander B cells and ICOS-driven motility. Nature 496, 523–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quast I, Dvorscek AR, Pattaroni C, Steiner TM, McKenzie CI, Pitt C, O’Donnell K, Ding Z, Hill DL, Brink R, et al. (2022). Interleukin-21, acting beyond the immunological synapse, independently controls T follicular helper and germinal center B cells. Immunity 55, 1414–1430.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin Q, Luo W, Mallajosyula V, Bo Y, Guo J, Xie J, Sun M, Verma R, Li C, Constantz CM, et al. (2023). A TLR7-nanoparticle adjuvant promotes a broad immune response against heterologous strains of influenza and SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Mater 22, 380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo W, Adamska JZ, Li C, Verma R, Liu Q, Hagan T, Wimmers F, Gupta S, Feng Y, Jiang W, et al. (2023). SREBP signaling is essential for effective B cell responses. Nat. Immunol 24, 337–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pardy RD, Gentile ME, Carter AM, Condotta SA, King IL, and Richer MJ (2022). An Epidemic Zika Virus Isolate Drives Enhanced T Follicular Helper Cell and B Cell-Mediated Immunity. J. Immunol 208, 1719–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.