Abstract

Dynamic assembly of macromolecules in biological systems is one of the fundamental processes that facilitates life. Although such assembly most commonly uses noncovalent interactions, a set of dynamic reactions involving reversible covalent bonding is actively being exploited for the design of functional materials, bottom-up assembly, and molecular machines. This Minireview highlights recent implementations and advancements in the area of tunable orthogonal reversible covalent (TORC) bonds for these purposes, and provides an outlook for their expansion, including the development of synthetically encoded polynucleotide mimics.

Keywords: dynamic covalent chemistry, dynamic materials, molecular assembly, molecular recognition, orthogonality

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Chemical Orthogonality

Nature has utilized billions of years of evolution to impart exquisite selectivity to essential chemical reactions that occur within organisms. One such example includes the catalytic activity and selectivity exhibited by enzymes, even in the complex chemical milieu of a cell. Additionally, the complementary supramolecular interactions of nucleic acid–base pairs favor Watson–Crick hydrogen bonding of guanine to cytosine and adenine to thymine.[1] These interactions are considered orthogonal in that they template the controlled pairing of C:G and A:T of DNA biopolymers, thereby imparting unique encoding information that is the basis of transcription, translation, and replication.

The term orthogonal in quantum mechanics is used to describe wavefunctions that have no overlap over all space.[2] No overlap is conceptually similar to no cross-reactivity, or 100% selectivity, and thus the term orthogonal has been co-opted to describe chemical reactivity. An early example is its use to exemplify the addition/removal of protecting groups under differing experimental conditions. The term was used by Merrifield in his 1977 report on peptide synthesis, when utilizing orthogonal deprotection schemes that occur in one pot without any cross-reactivity,[3] and more recent peptide derivatizations.[4] There are even methods for chemically similar functional groups, with an example being the selective deprotection by Wong et al. of different saccharide hydroxy groups during the synthesis of oligosaccharide libraries.[5,6] The syntheses of complex natural products and pharmaceuticals are so reliant on orthogonal protecting groups that chemists now seek to streamline their syntheses by lowering their necessity, as recently reported by Baran and Richter in the protecting-group-free synthesis of hapalindole Q.[7]

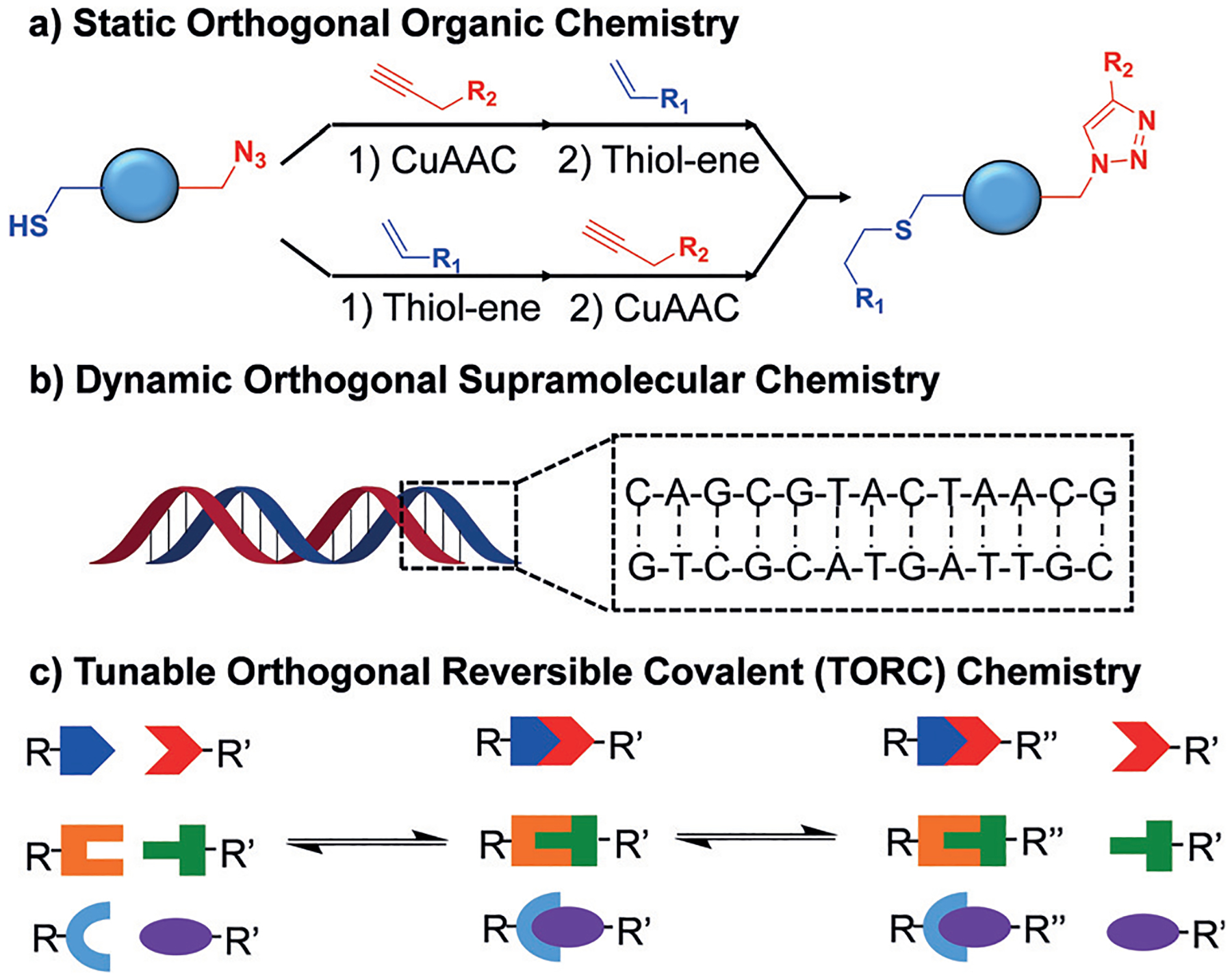

The development of orthogonal coupling strategies is also an area of interest. It has led to the controlled synthesis of complex dendrimers,[8] orthogonal ligation of peptides,[9] and orthogonal synthesis of branched polyethylenes.[10] Furthermore, the rise of “click” reactions has led to the realization of orthogonality between various complementary “click” pairs. The utilization of two or three of these orthogonal “click” reactions (Figure 1a), which include copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloadditions (CuAAC), thiol–ene click, oxime condensation, and Diels–Alder reactions, in polymeric systems has expanded the breadth of functional materials, allowing for tailorable properties that cannot be accessed through traditional polymerizations alone.[11]

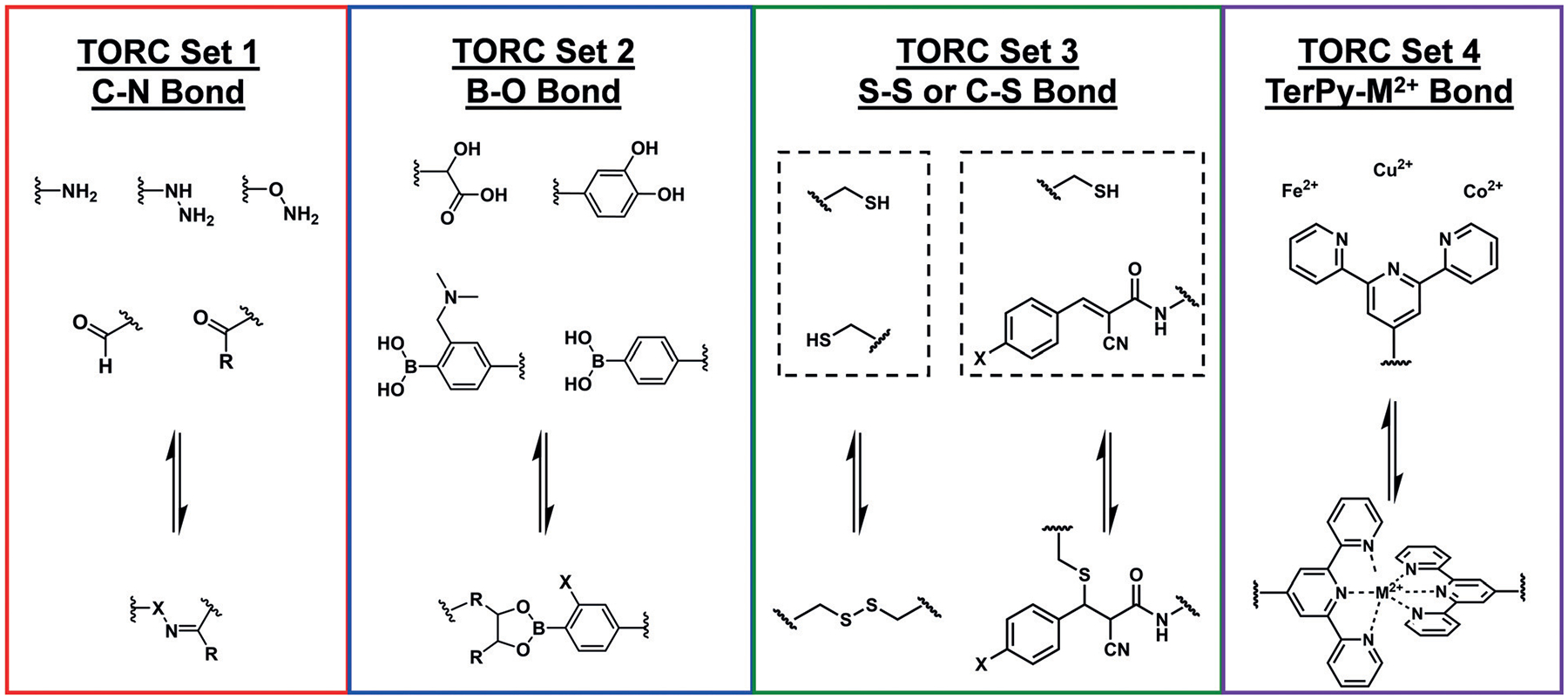

Figure 1.

Examples of chemical orthogonality including a) more traditional static orthogonal organic transformations such as CuAAC and thiol–ene click, b) orthogonal supramolecular interactions such as the complementary hydrogen bonds of DNA, and c) dynamic TORC bonds that exchange covalently only with complementary partners.

Many click reactions have also found applications for the fast, efficient labeling of biopolymers. The reactions that have proven orthogonal to the reactive functionalities present in biopolymers were coined as bioorthogonal by Bertozzi and co-workers in 1997.[12] Since this seminal work, bioorthogonal chemistry has been one of the most impactful and widely utilized techniques for labeling biomolecules within a live cell.[13] This expanded the marriage between organic chemistry and chemical biology by enhancing the repertoire of biological labeling strategies and opening new possibilities at the interface of chemistry and biology.

1.2. Tunable Orthogonal Reversible Covalent (TORC) Bonds

Outside the traditional context of orthogonal organic transformations lies the utilization of orthogonal supramolecular interactions. The paradigmatic orthogonal supramolecular interaction in nature is the complementary hydrogen bonding of base pairs of nucleic acids (Figure 1b). Unnatural analogues of orthogonal, complementary hydrogen-bonding moieties have been utilized along with metal–ligand coordination chemistry and/or electrostatic interactions.[14]

Intersecting both organic and supramolecular chemistry is the field of dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC), which has been focused on the thermodynamic and kinetic control of reversible covalent bonds.[15] DCC is employed in a variety of applications, including self-healing polymers,[16] rapid drug discovery through dynamic combinatorial libraries (DCLs),[17] and sensing.[18] However, the utility of having a suite of complementary and orthogonal pairs is just beginning to be realized.[19]

With this in mind, we introduce the acronym TORC, for “tunable orthogonal reversible covalent” chemistry (Figure 1c). Bonding moieties that fit in the context of TORC bonds must be tunable in nature, in that they can be replaced by other, similar functionalities to alter the kinetics and thermodynamics of the reversibility. Additionally, there must be no reactivity between noncomplementary TORC bonds because of their orthogonal and reversible nature. Finally, TORC chemistry also provides the robust nature of covalent bonds, thus expanding the utility of these interactions past traditional supramolecular chemistry.

In this Minireview we survey the literature on TORC bonds, starting from sets of two TORC pairs and increasing to four TORC pairs. We first outline the various experiments that have been carried out to prove orthogonality and how their tunability can be applied. Furthermore, we review some unique applications of TORC chemistry. Finally, we provide an outlook on the future potential of TORC bonds pertaining to novel applications that have yet to be achieved.

2. Proof of Orthogonality and Tunability

The test of chemical orthogonality requires a variety of experimental approaches to support no cross-reactivity between functional groups that are noncomplementary. Furthermore, changing the order of addition/reaction for two or more orthogonal reactions should not alter the distribution of products formed, showing no cross-reactivity. In 2001, Lehn and co-workers introduced the concept by using DCLs of imine formation and terpyridine–metal complexation.[17] Since this study, the diversity of TORC bonds has grown from two-component systems to a recent report simultaneously utilizing four dynamic TORC bonds in unison.[20]

2.1. Two-Component TORC Chemistry

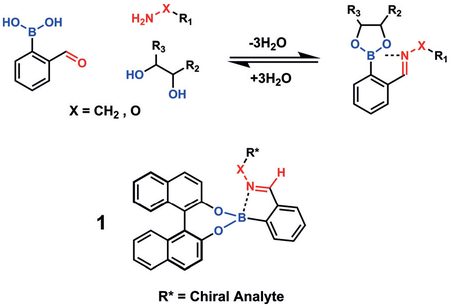

One set of TORC pairs implemented simultaneously on a single scaffold is the coassembly of diols and amines onto 2-formylphenylboronic acid (2-FPBA) to form imines and boronic esters orthogonally [Eq. (1)].[21] In fact, the two binding events cooperatively reinforce one another, a unique facet that has not been demonstrated with other TORC pairings.[22] Furthermore, the formation of oximes and hydrazones demonstrate the tunability in this multicomponent assembly.[23] They exploited this one-pot condensation with chiral amines of various enantiomeric purity and enantiomerically pure 1,1’-binaphthol (BINOL) to form 1 as diastereomers that are capable of being distinguished by 1H NMR spectroscopy for determination of the enantiomeric excess (ee).

Other reports have demonstrated complete orthogonality between imine and disulfide exchange,[24] as well as hydrazone and disulfide exchange.[25] The experiments used to prove orthogonality include NMR spectroscopy and analytical HPLC. By using these techniques, it has also been shown that hydrazone/imine exchange occurs in acidic environments, whereas disulfide exchange is accelerated in basic media, thereby allowing for a differential pH responsivity.

|

(1) |

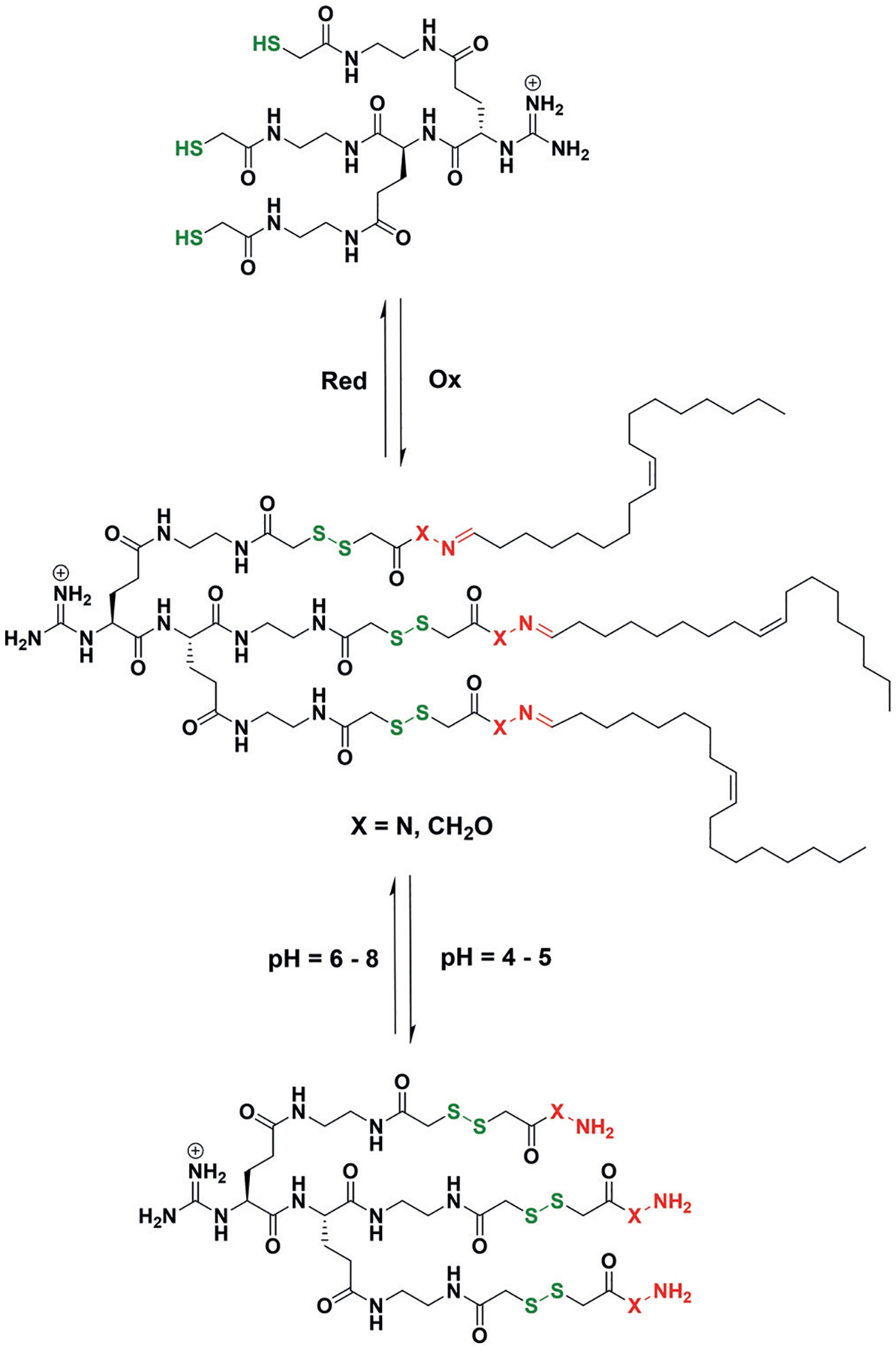

Riezman, Matile, and co-workers reported an example of tunability in TORC systems in 2013 (Scheme 1).[26] The authors utilized combinations of disulfides and hydrazones/oximes for the synthesis of amphiphilic dendrimer DCLs with more than 900 members. This large library of amphiphiles was screened for their ability to encapsulate and deliver siRNA to cancer cells. This utilization of multiple TORC bonds led to two sites within the amphiphilic dendrimer structures that could be cleaved by different stimuli (e.g. pH changes or redox chemistry), thus allowing the simultaneous modulation and screening of multiple release mechanisms. Furthermore, the differences in the stability of hydrazones versus oximes in aqueous environments allowed the facile alteration of reversibility within the same TORC bonding class, thereby demonstrating the tunability of TORC bonds in their DCLs.

Scheme 1.

Two members of a dynamic amphiphile library with doubly responsive TORC triggerable release of cargo. Triggers can be both redox chemistry to cleave the disulfide bonds (green) or pH-controlled hydrolysis of hydrazone/oxime (red) TORC bridges.

2.2. Three- and Four-Component TORC Chemistry

In the vast majority of examples, two TORC bonds are utilized in parallel to build complex topological structures and diverse DCLs. If additional dynamic covalent reactions were found to possess multicomponent orthogonality, the degree of complexity and diversity in the molecular architectures and DCLs, respectively, would increase dramatically. The first example expanding the TORC bonding family was reported in 2007 when Nitschke and co-workers demonstrated three dynamic equilibria were established in unison by using exchangeable imine, disulfide, and metal coordination to assemble large, bimetallic metal complexes.[24b] In these unique complexes, all the TORC components could be dynamically exchanged on demand through the introduction of competing amines, thiols, and metal salts.

In 2015, Matile and co-workers extended the three-component TORC chemistry and showed full chemical orthogonality in the formation and exchange of boronic esters, hydrazones, and disulfides in one pot.[27] In several reports, this group details the complex assembly of colorful surface architectures by using these three reactions concurrently. These three TORC sets were further used by Bonifazi and co-workers to template the assembly of fluorophores onto peptide oligomers.[28]

The most recent expansion of TORC chemistry was reported by our group, where terpyridine–metal complexation was dynamically exchanged with three different organic TORC bonding partners in one pot: boronic ester exchange, hydrazone exchange, thiol–Michael exchange (instead of disulfide exchange).[20] Additionally, these TORC reactions were designed to exchange under physiological conditions (pH 7.4), thus extending their potential applications to the biological sciences. This report utilized exchange reactions between thiols and activated alkenes (Michael acceptors; TORC Set 3 in Figure 2) as TORC bonding pairs, thus offering another opportunity for tuning the reactivity.

Figure 2.

Four distinct pairs of TORC bonds with different tunability options, including dynamic C–N, B–O, S–S/S–C, and TerPy–M2+ bond exchange with programmable kinetic and thermodynamic parameters by attenuating the nucleophilic or electrophilic character of individual TORC bonding partners.

We have stressed the importance of the tunability present within TORC bonding schemes (Figure 2). For example, amines, hydrazides, and hydroxylamines have been readily interconverted within TORC systems, but the tunability of the other sets are only beginning to be realized. For TORC Set 2, exchanging the “diol” source from catechols to α-hydroxy-carboxylic acids to carbohydrates offers one avenue for tuning the reversibility, as does the addition or subtraction of aminomethyl substituents ortho to the phenylboronic acids.[29] The utilization of the activated alkene conjugate acceptor offers a handle for tunability in TORC Set 3. We have previously demonstrated that altering the electronics of the Michael acceptor ring (i.e. changing the substituent X in Figure 2) affects the kinetics of thiol exchange.[30] Finally, terpyridine complexation can be tuned either by using substituted ligands or altering the metal center itself.[31]

3. Complex Molecular Assembly

Molecular self-assembly is the process by which smaller molecular components adopt a larger defined structure without the control of an external source.[32] Traditionally, molecular assembly has utilized supramolecular interactions due to the irreversible, that is, non-error correcting, nature of covalent bonds. However, significant progress has been made utilizing TORC-based systems.

3.1. TORC-Driven Structural Assembly

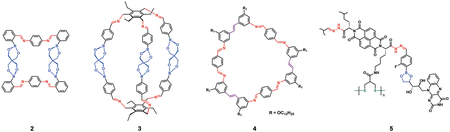

Although dynamic covalent bonds have been utilized for combinatorial libraries and molecular assembly for some time, it wasn’t until the 2000s that they were described as orthogonal, and only recently have they been used for the specific role of complex assembly. For example, Nitschke and co-workers reported one of the first demonstrations, the creation of an iminoboronate-based assembly, wherein control was derived from the electronic properties of the diols and diamines, thereby creating macrocycles such as 2.[33] Shortly thereafter, Severin and co-workers reported the synthesis of macrocyclic cage 3 by utilizing 2 TORC pairs and a ball-milling approach. Their method efficiently brought together 11 building blocks through the formation of 18 covalent bonds.[34] This showcased the robust ability of TORC bonds to self-assemble small components into higher-ordered structures with high fidelity.

Zhang and co-workers published a series of papers describing the one-pot synthesis of shape-persistent macrocycles by using imines to drive formation of a construct, followed by olefin metathesis to build macrocycles, such as 4.[35] This is an example of olefins being used as TORC pairs. In this system, tunability is key because the formation of the imine prior to olefin metathesis is required, as the amines poison the metathesis catalyst. Furthermore, the imines could be reduced to lock the structures for characterization, thus showcasing the ability of TORC chemistry to self-assemble discrete structures, which can then be irreversibly locked.[36]

As described in Section 2.2, the first examples of three-component TORC assemblies were reported by Zhang and Matile.[37] In their study, disulfides, hydrazones, and boronic esters were used to build discrete multicomponent architectures such as 5. By incorporating boronic acids into the architectures, the authors were capable of binding and detecting natural product catechols by using an indicator-displacement assay with alizarin red. These are just a handful of examples describing the use of TORC pairs to drive the assembly of discrete complex molecular structures and the study of their assembly.

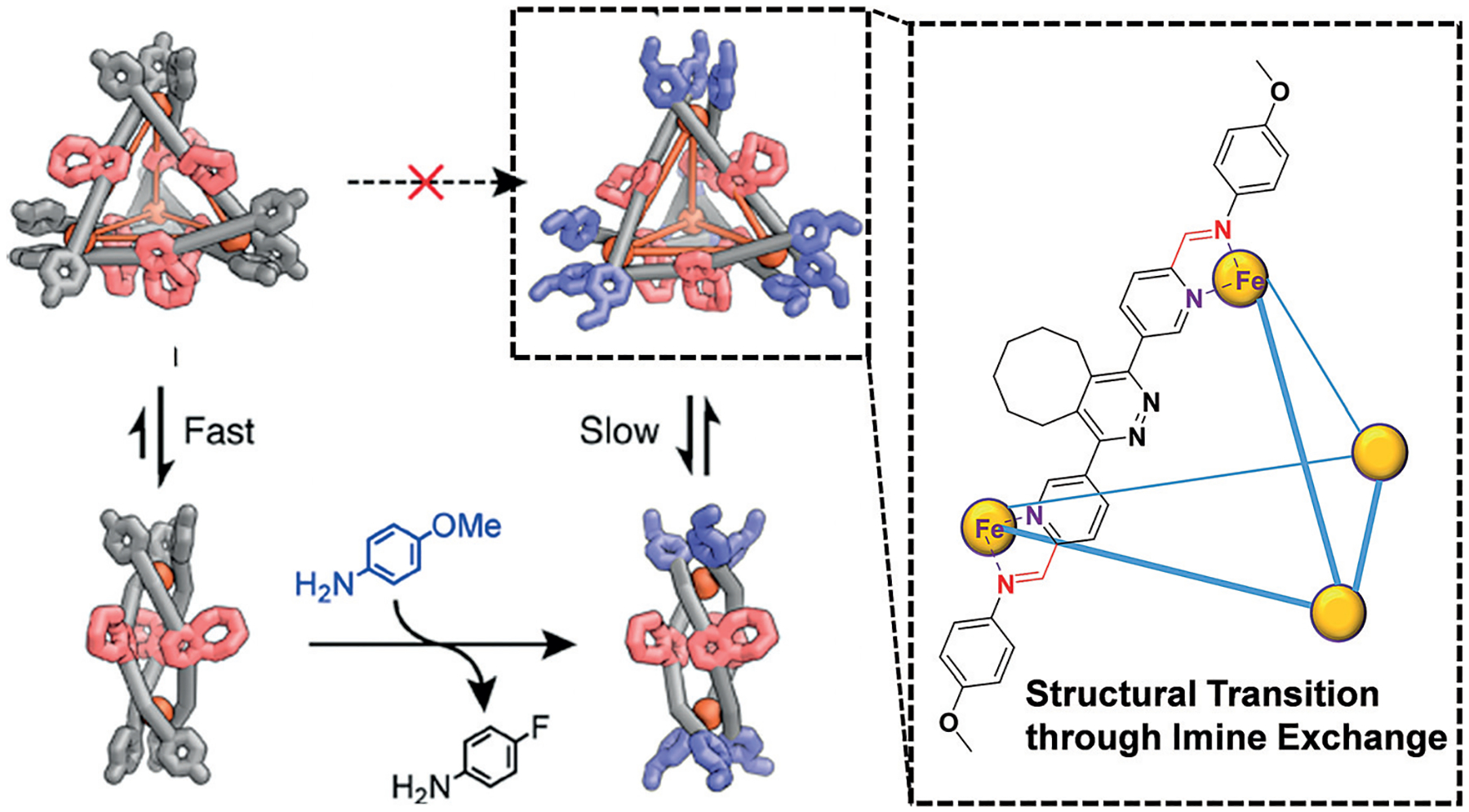

The use of imine condensation and metal complexation cooperatively has led to the construction of a wide array of different types of complex molecular ensembles.[38] One of the most recent and elegant example of TORC chemistry was reported by Nitschke and co-workers in their construction of dynamic metal-organic cages assembled from combinations of imine condensation and metal coordination/stabilization.[39] Another recent example also demonstrates the tunable utilization of these TORC bonds in unison to alter the complex molecular structures through reversible exchange of one imine for another (Figure 3).[40] In this recent report, unique metal-organic helicate assemblies were constructed through imine formation with 4-fluoroaniline and 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde derivatives in conjunction with Fe2+ complexation. Upon exchange of the electron-deficient 4-fluoroaniline for the more electron-rich 4-methoxyaniline, a structural transition from the original helicate molecular assembly to a pyramidal metal-organic cage was observed.

Figure 3.

An example of multicomponent assembly reported by Nitschke and co-workers, who utilized the cooperative condensation of an imine and complexation of Fe2+ to form complex metal-organic cages. Exchanging 4-fluoroaniline for 4-methoxyaniline induces a post-assembly structural transition from two metal-ion helicates to a pyramidal arrangement with four metal ions. Adapted from Ref. [44] with permission from the American Chemical Society.

3.2. Receptor Formation and Molecular Sensing

The use of dynamic orthogonal covalent chemistry for the creation of combinatorial libraries is well-described in the literature.[41] Likewise, these libraries often utilize the binding event of a guest to define the structures of the hosts. While frequently generating unique and interesting structures, these systems tend to not utilize the tunable aspect of TORC pairs. As such, our focus will be on systems that utilize the orthogonality and tunability of specific pairs to modulate the binding.

Furlan and co-workers described a system of hydrazones and disulfides to prepare dynamic combinatorial libraries, wherein the orthogonal bonds provide greater levels of diversity.[42] For example, macrocyclic lithium receptor 6 was built and optimized using a hydrazone exchange with a masked disulfide, which was allowed to equilibrate under acidic conditions over six days, thereby forming macrocycles with two and three units in near equal proportions. Utilizing the monomer’s known lithium-binding properties, the cyclization was carried out in the presence of LiBr to drive the reaction to 99% cyclic trimer. After unmasking the thioester side chains, the macrocycle was functionalized through disulfide exchange to form 6, thus tuning the reaction towards the binding of lithium.

Our group reported an assembly where reversible imine formation between chiral amines and 2-formylpyridines, followed by coordination of the pyridine ring to an iron center, creates discrete structures that are circular dichroism (CD) active.[43] The assembly was used to determine the ee value of the amines. We also investigated the tuning of the aldehyde to enhance the rate of imine formation. The introduction of an ortho hydroxy group led to the rate of imine formation increasing from 2 h to less than 10 s, presumably as a result of formation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond (7). Similar multicomponent assemblies generated from 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde (PCA), di(2-picolyl)amine, and zinc triflate were reported for determining the ee value of chiral alcohols.[44] The secondary amine condenses with PCA reversibly to form an iminium ion, which quickly adds the alcohol to form a hemiaminal. The hemiaminal is trapped through zinc coordination (8), and the resulting helical twist of the pyridines give CD signals that enable the ee value of the alcohol to be deduced.

A unique probe for polyphenols was described by Matile and co-workers, where anthrylhydrazides were allowed to react with formylphenylboronic acids to give hydrazinoan-thrylboronic acids, which were then mixed with catechols to give the multicomponent assembly 9.[45] By utilizing an anthrylhydrazine, the assembly has a distinctive exciton-coupled CD signal that depends upon the structure of the boronic acid probe and catechol analyte. Thus, the authors were able to sense epigallocatechin gallate, one of the key components of green tea.

Recently, Nitschke and co-workers reported several examples of particularly unique TORC receptors that utilize metal-organic cages similar to those described in the previous section for the selective encapsulation of a variety of guests.[46] In the most recent example, their cages were employed for the selective extraction of high-value anions such as ReO4− and TcO4− from water, even in the presence of as many as ten different anions.[47] This is a particularly elegant example of utilizing TORC chemistry in combination with supramolecular analytical chemistry for the purposes of water purification.

This is far from a comprehensive display of the application of TORC bonds in molecular sensing ensembles, but it does demonstrate the use of multi-TORC systems and their specific sensing capabilities.

3.3. Molecular Motors

Molecular machines are perhaps one of the most important and unique adaptations of TORC chemistry. These intricate systems were among the first examples of controlled molecular-level motion.[48] Directed movement is the basis for many biological processes and, as such, mimicking these natural systems inspires artificial molecular designs.

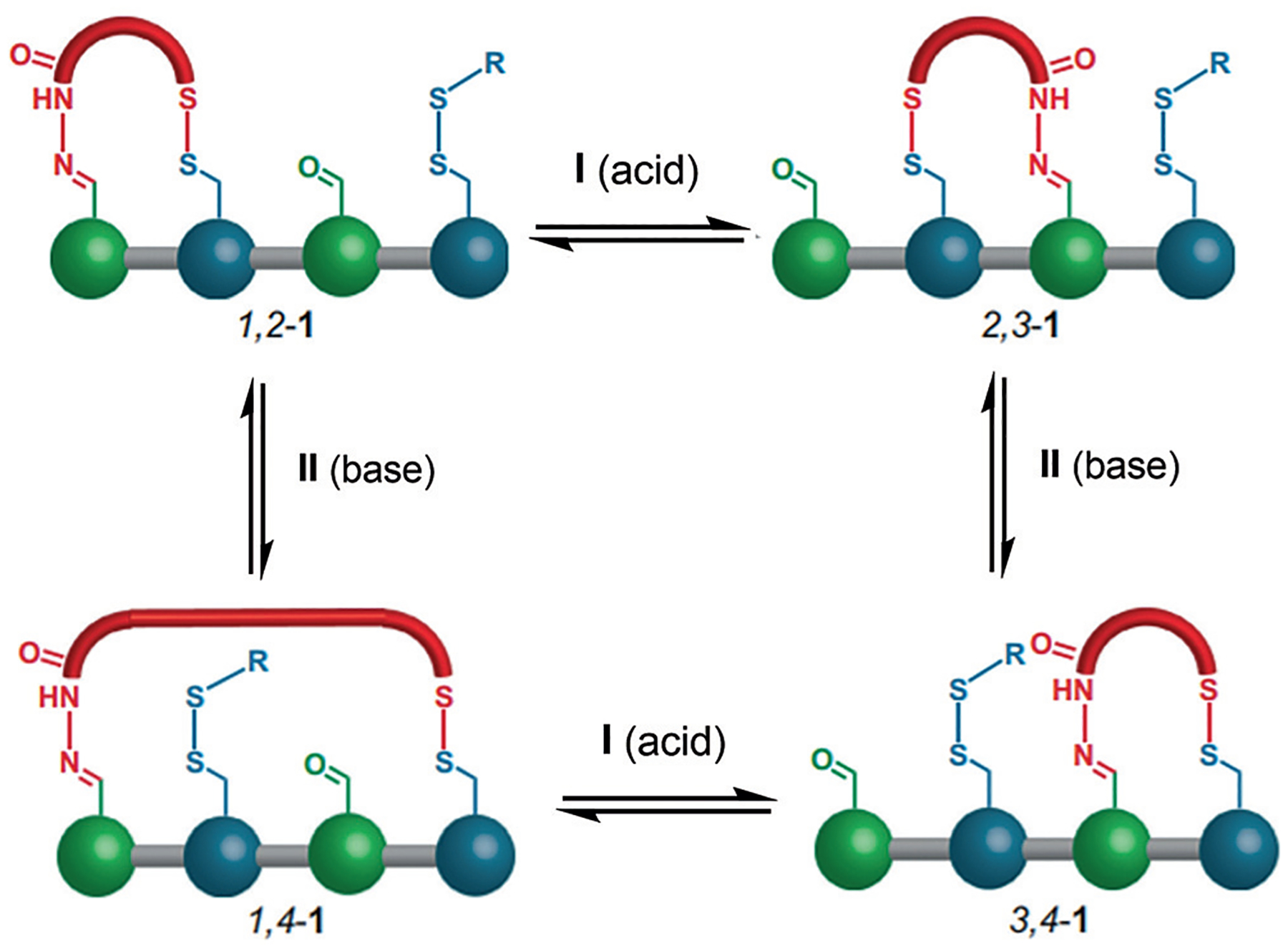

Leigh and co-workers described a “molecular walker” that is transported along a short molecular track, similar to how kinesin walks along a microtubule track.[49] The walker (red in Figure 4) moves one attachment at a time between the footholds on the track, by using the hydrazone/aldehyde and thiol/disulfide TORC pairs, which can be triggered under different conditions. The orthogonal triggering is key to the system, as one attachment is required any time the other “foot” is moving, lest the walker be released into the solution. Treatment with trifluoroacetic acid leads to approximately a 50% distribution of 1,2–1 and 2,3–1. By switching to a basic and reducing system, the hydrazone exchange is slowed dramatically, thereby locking one foot into place, and the disulfide exchange becomes reversible and leads to the 3,4–1 conformation. Interestingly, no matter what the starting point, the walker will reach the same steady-state minimum distribution after multiple cycles. Thus, the authors went on to use irreversible redox conditions, putting the reaction under kinetic control, and thus conferring modest directionality.[50] Another example uses a light-induced “switch” to confer directionality onto the walker, by using a stilbene-based cis–trans isomerization.[51] Further examples include a nitrostyrene and oligoethylenimine track, wherein intramolecular Michael and retro-Michael reactions move the small molecule in a nondirectional fashion,[52] as well as enzyme-driven directionality,[53] metal complexation directionality,[54] and thermodynamic directionality.[55]

Figure 4.

Molecular walker that utilizes an alternating formation of a hydrazone and disulfide to move the molecule down the track. Trifluoroacetic acid is used in step I to exchange hydrazides, and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) and dithiothreitol (DTT)used in step II to exchange thiols. Adapted from Ref. [48] with permission from Springer Nature.

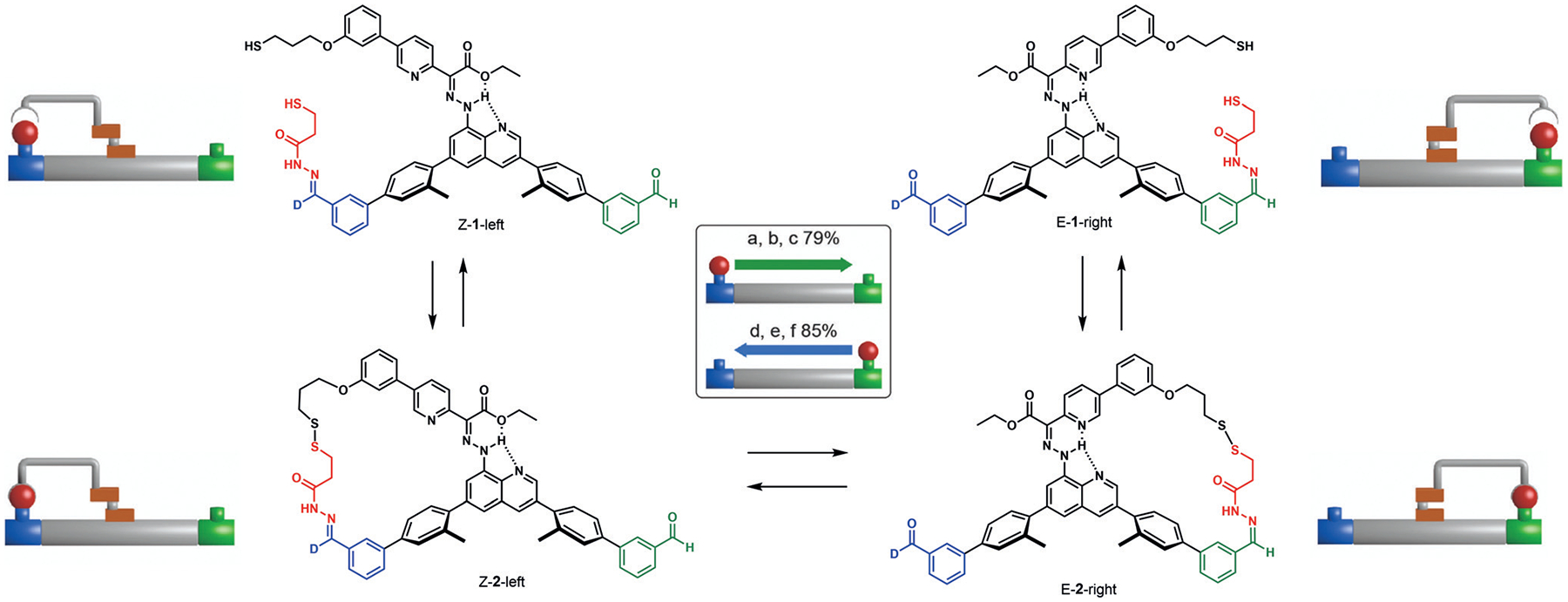

This same group has demonstrated the ability to transport cargo from one end of a molecule to the other.[56] The system utilizes two TORC pairs: a hydrazone/aldehyde pair to attach the cargo to either end of the platform, and a thiol/disulfide exchange with which to bind the cargo to the robotic arm. Thus, orthogonal exchange allows the cargo to bind first to one end of the platform and then to the arm, before being released from the platform and then rebinding to the other end of the platform (Figure 5). Transport of the cargo is controlled by configurational changes within a hydrazone rotary switch. This machine is capable of transporting 3-mercatopropanehydrazide in 79–85% yield to the opposite end of the platform without the cargo dissociating or exchanging with other molecules in solution. Another example describes a catenane rotary motor consisting of hydrazone and disulfide TORC pairs that is driven by pulses of chemical fuel, reminiscent of biological systems using ATP.[57] Pulsing acidic and basic conditions releases the TORC pairs selectively to allow for directional movement of the catenane rotary motor. Although there are other interesting examples of molecular machines,[58] the ones described herein utilize TORC pairs quite effectively.

Figure 5.

Structure and schematic representation of the molecular robotic arm developed by Leigh and co-workers that utilizes hydrazone and disulfide formation to move the cargo. Adapted from Ref. [56] with permission from Spinger Nature.

4. Dynamic Materials

In the context of functional materials, TORC chemistry offers promising avenues for the creation of complex molecular architectures. Although dynamic covalent bonds have been used in materials research for some time, it is only recently that multi-TORC chemistry has made its way into these systems, helping to address challenges in the synthesis of self-sorting, self-healing, and replicating materials.

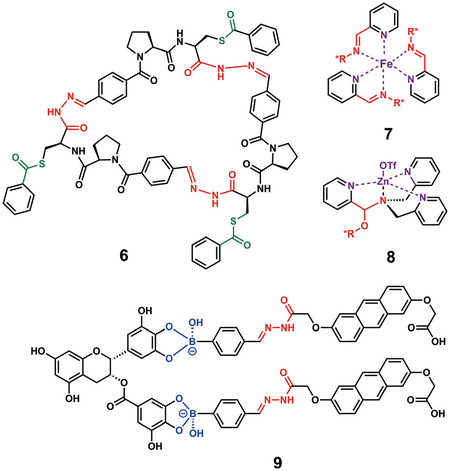

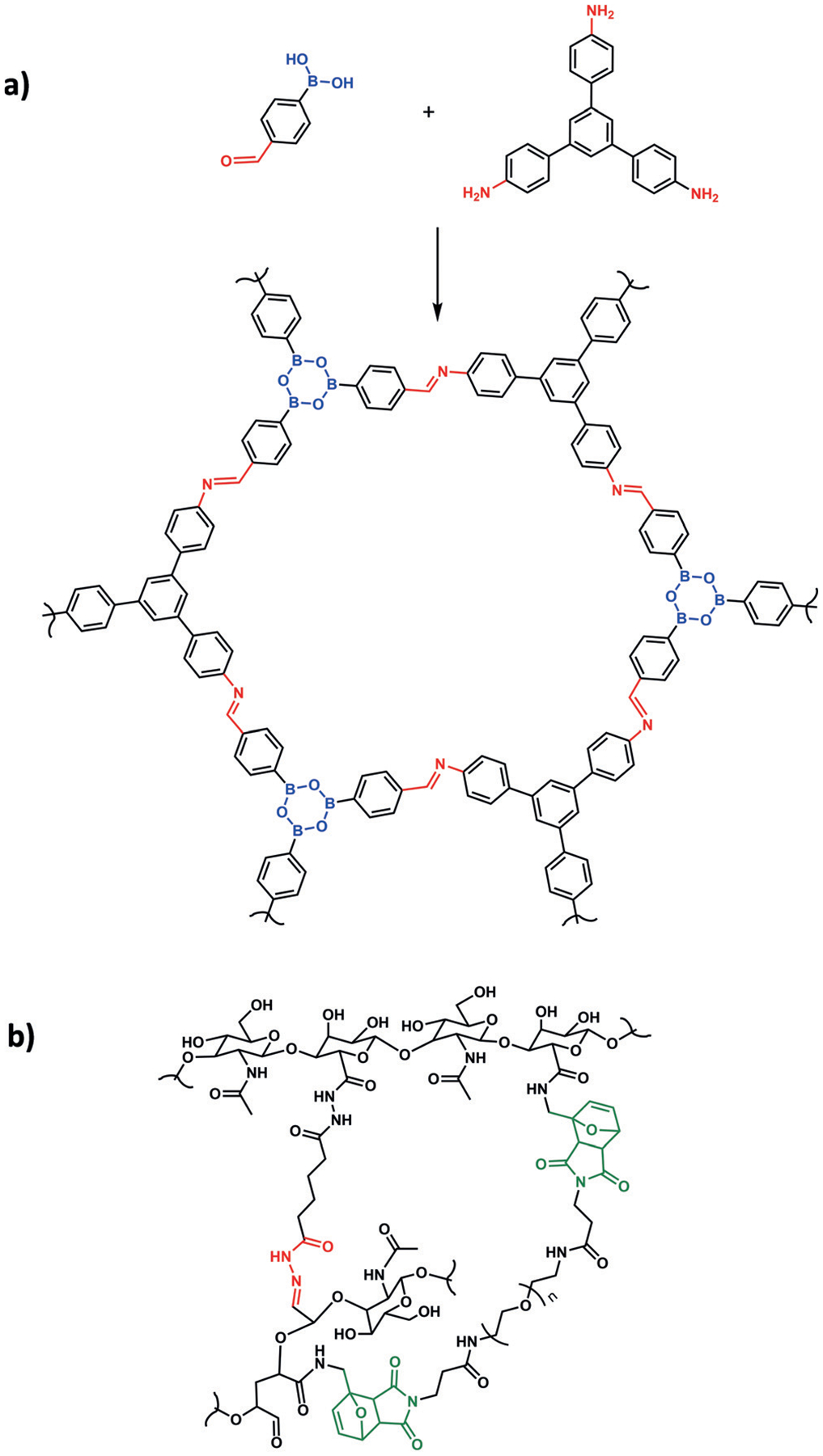

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are a class of porous materials whose structures can be predetermined by choice of building blocks and are made entirely of concatenated organic groups. These precisely organized structures maintain a permanent porosity and low density, thus giving them unique applications.[59] Dynamic and reversible covalent bonds are required for self-sorting and healing, since permanent linking would lead to the formation of amorphous materials. The application of multiple TORC pairs in COFs was first reported in 2015 by Zhao and co-workers,[60] who used two common condensation reactions—imine and boronic ester formation—to build binary and ternary COFs with a high capacity for H2 gas adsorption (Figure 6a). In a follow-up study, the authors reported the first multi-TORC COF with heterogeneous porosities.[61]

Figure 6.

a) A covalent organic framework with boronic esters (blue) and imines (red). b) Hydrogel based on hyaluronic acid cross-linked with a Diels–Alder reaction (green) with incorporated hydrazones (red) to provide dynamic healing properties.

Self-healing materials, specifically polymers, have utilized dynamic covalent chemistry as an intrinsic repair mechanism that does not require the addition of a repair agent.[62] The use of self-healing TORC chemistry is demonstrated in a recently reported dynamic hydrogel.[63] By using disulfide-containing bishydrazones to link a trialdehyde-functionalized PEG polymer, the hydrogel was capable of repairing itself under both acidic and basic conditions. Interestingly, the self-healing could be stopped by kinetically locking the exchange at pH 7, and externally reactivated by the addition of a catalytic amount of aniline to accelerate acylhydrazone exchange. In an another example, Diels–Alder and acylhydrazone TORC pairs were combined to build a multifunctional hyaluronic acid based hydrogel (Figure 6b).[64] The furan–maleimide Diels–Alder reaction was used to cross-link the hydrogel and provide the desired physiochemical properties, such as elasticity and shape-recovery, with the aim of creating an engineering scaffold for cartilage tissue.

A less explored application of TORC pairs involves their use in the triggered assembly and disassembly of polymers and nanoparticles. By using TORC bonds, Fulton’s group was able to build acrylamide-based linear copolymers with disulfide and aldehyde/amine appendages.[65] The copolymer chains were cross-linked through imine formation by using a pH 8 trigger. After disulfide exchange, polymeric nanoparticles with a hydrodynamic radius of 76 nm were assembled. Notably, the particles were capable of encapsulating hydrophobic molecules. By reducing the pH value to 5.5 to increase the rate of imine exchange, and adding the reducing agent tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to cleave disulfide cross-links, the polymeric nanoparticles were disassembled into their constituent polymeric monomers, thereby releasing the encapsulated cargo. Interestingly, the sole application of TCEP or a lowering of the pH value did not trigger disassembly and the nanoparticles maintained their structural integrity.

5. Future Outlook: TORC-Encoded Assembly

By using synthetic DNA oligomers, researchers have successfully combined the natural templating abilities of DNA and synthetic coupling procedures for the nucleotide backbone to autocatalytically replicate individual DNA molecules without the need for polymerase chain reactions (PCR).[66] Furthermore, many replicators using reversible covalent bonding have now been reported, but each primarily uses one reversible covalent interaction.[67] In contrast, the use of a suite of TORC bonding pairs offers a route to encode for information storage through the dynamic exchange of up to, and ultimately beyond, four TORC “genetic” pairs.

5.1. Expansion of the TORC “Code”

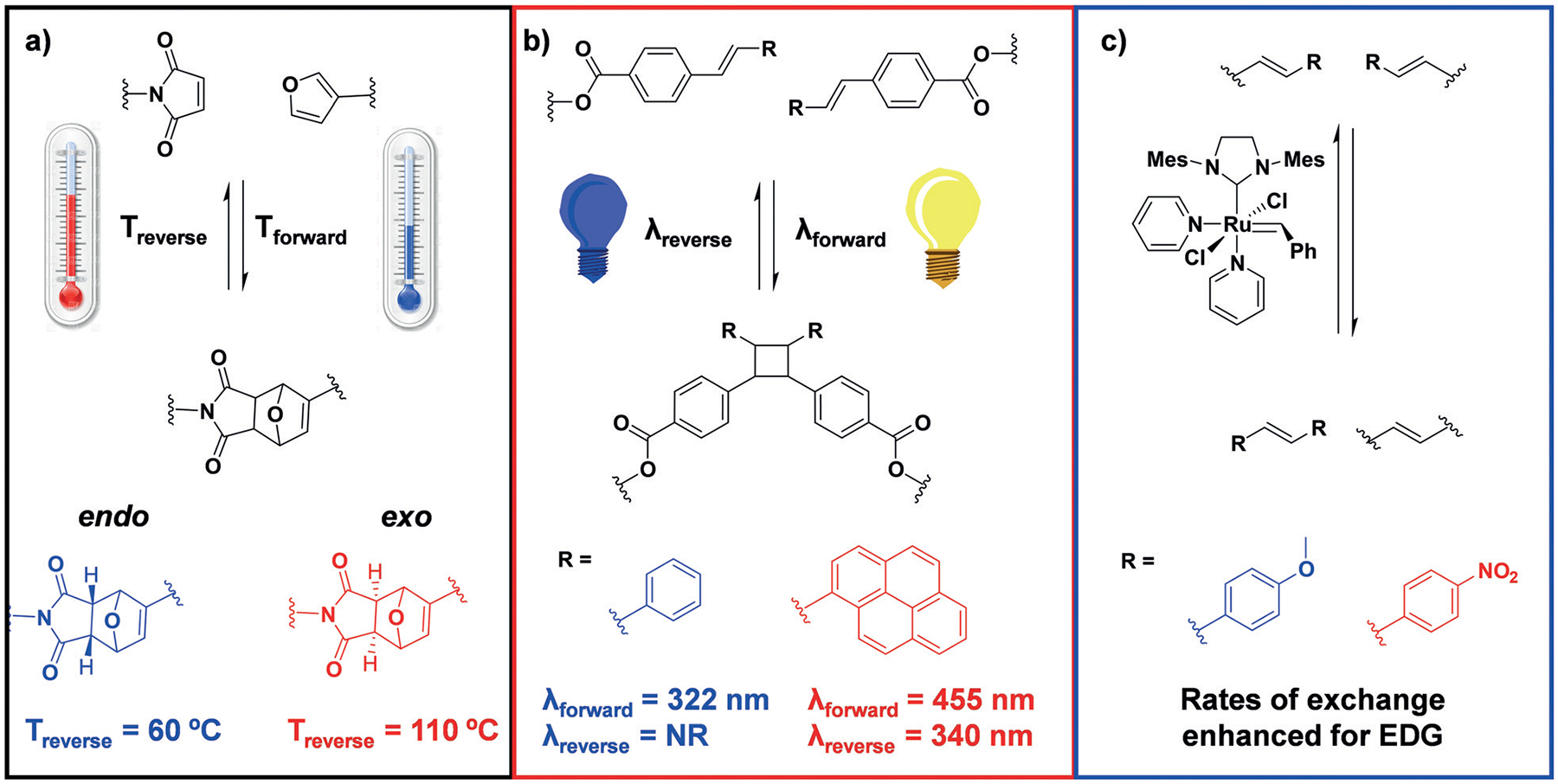

Within the context of materials science and polymer chemistry, the thermally reversible Diels–Alder reaction between substituted furans and maleimides has been heavily utilized, and some examples were outlined in Section 4.[68] This additional TORC pair offers alternative stimuli for triggered association through thermal control. Additionally, the endo- and exo-Diels–Alder products reverse at different temperatures (ca. 60°C versus 110°C, respectively; Figure 7a), thus offering routes to tunability that have yet to be explored in the context of chemical assembly.[69] The cross-reactivity of the maleimide TORC group with thiols could prove detrimental due to the propensity for thiol–maleimide conjugate addition, but these TORC functional groups have already shown orthogonality when paired with hydrazone formation.[64]

Figure 7.

Proposed expansion of the TORC “code” by utilizing dynamic covalent bonds that can be triggered using specific stimuli: a) thermally reversible Diels–Alder reaction between maleimides and furans, b) reversible photoinduced [2+2] cycloaddition of stilbene derivatives, and c) ruthenium-catalyzed olefin metathesis. Some proposed tunability options for each new TORC set are also shown. EDG=electron-donating group, Mes=mesityl.

Reversible photoinduced cycloaddition reactions have yet to be incorporated into multicomponent TORC systems, and thus their level of orthogonality to other TORC bonding members is still largely unknown. These types of reactive groups would offer a facile trigger for controlled assembly/disassembly as well as the use of alternative stimuli orthogonal to pH or temperature changes. Specific examples include [2+2] cycloadditions of 3-cyanovinylcarbozole with thymine[70] and the dimerization of styrylpyrene[71] (Figure 7b). These reactions undergo cycloreversion when exposed to light of shorter wavelength. The styrylpyrene cycloaddition has recently been utilized in the reversible dimerization of end-functionalized polyethylene glycol systems.[72] Furthermore, [4+4] cycloaddition dimerization reactions can be achieved with triazole-substituted anthracene derivatives by using visible light to drive the dimerization and UV light to facilitate cycloreversion.[73] Recent advances in the field of dynamic covalent cyclization reactions that can be induced and reversed at different wavelengths of light were detailed in a recent review by Barner-Kowollik and co-workers.[74]

In addition to the use of physical stimuli to control TORC bond formation and reversal lies the possibility for chemical or catalytic control. One such example includes transition-metal-mediated olefin metathesis with dynamic exchange of alkenes to form new C=C bonds. Olefin metathesis has been utilized previously as a TORC bonding set in conjunction with imine bond formation, as noted in Section 3.1.[35] The kinetics of olefin exchange can be altered simply by altering the substituent attached to the alkene. For example, the exchange reaction of olefins with para-substituted phenyl substituents occur at very different rates, that is, electron-donating groups exchange faster than electron-withdrawing groups (Figure 7c).[75]

5.2. TORC-Mediated Information Transfer

Just as the DNA base pairs represent a language that carries information inherent in its sequence, TORC pairs can be envisioned to play similar roles. Research in the field of DNA self-assembly has extended well past its traditional biochemical and genetic roots with the development of DNA origami, logic gates, molecular motors, and encoded nanoparticle assembly, to name a few.[76] The utility of TORC chemistry promises similar applications.

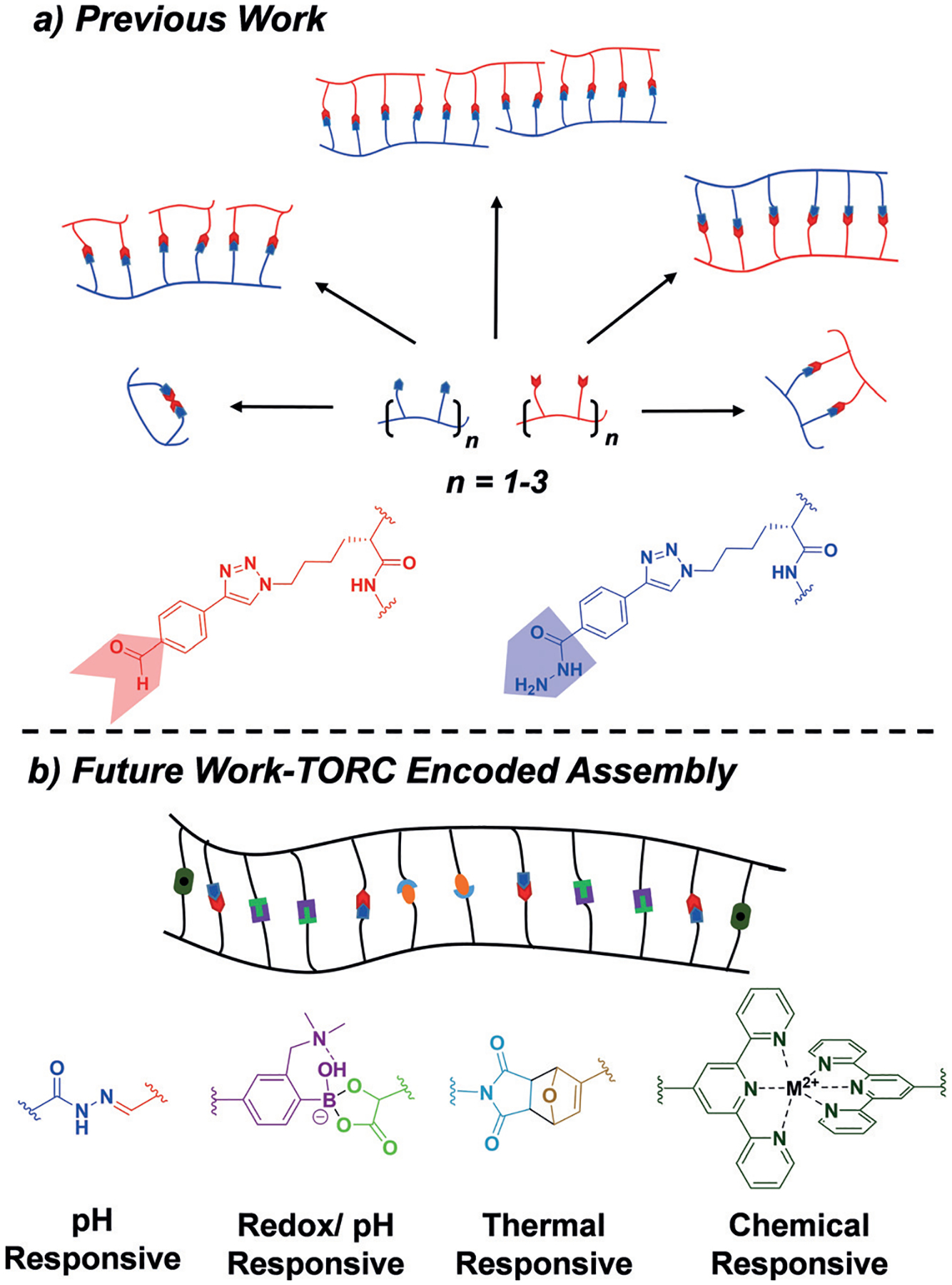

Currently, we are working on the incorporation of TORC bonding partners into synthetic oligomers of peptides and other unnatural analogues. We recently introduced aryl aldehyde and acyl hydrazide functionalities into peptide-based oligomers.[77] This TORC pair was utilized to induce formation of quaternary structures such as macrocycles, zipper-like structures, multiloop macrocycles, and ladder polymers in a highly controlled manner (Figure 8a). These distinct topologies were found to have different effects on the antimicrobial properties of peptides, showing an enhancement in the inhibition of gram-negative bacterial growth, even versus drug-resistant strains of E. coli and A. Baumannii.[78]

Figure 8.

a) TORC-mediated assembly of aldehyde- and hydrazide-functionalized peptide oligomers into topologically diverse quaternary assemblies including macrocycles, zipper-like structures, multiloop macrocycles, and ladder polymers. b) This work has initiated the current research goal of designing sequence-specific TORC oligomers with a defined TORC code that templates the macromolecular assembly in an analogous manner to DNA.

However, these recent advancements used only one TORC pair. One goal is to utilize multiple TORC bonding functionalities in unison to further increase the complexity of the peptide quaternary structures. The first iteration of this included the combination of bipyridine–metal coordination with hydrazone condensation to form sequence-specific multiloop macrocycles containing two peptides within the quaternary structure.[79]

Our current focus is on the incorporation of multiple TORC pairs into a single oligomeric system, thereby allowing for encoded macromolecular assembly and controlled folding. Toward these efforts we recently reported the incorporation of o-aminomethylboronic acid moieties onto peptides through the alkylation of secondary amines.[80] This approach can be utilized as an orthogonal route to the incorporation of hydrazides or aldehydes through click reactions.

In addition, encoded synthetic oligomers can be envisioned to orthogonally assemble from smaller TORC “codons” onto a larger template oligomer, thus drawing substantial comparisons to DNA and RNA biomacromolecules (Figure 8b). TORC chemistry, however, offers potential opportunities to expand the orthogonal codon to a four, or potentially more, code system, thereby allowing for additional potential for information storage compared to that of two pair DNA systems. Furthermore, the tunability inherent in TORC bonds allows for tailorable and triggerable association and dissociation, thus allowing for “codes” to be switched on and off.

6. Summary

Tunable orthogonal reversible covalent (TORC) bonding has found uses in a variety of disciplines, dating back to original applications in DCLs. However, it is when numerous TORC bonding pairs are combined that very high levels of chemical complexity and assembly can be controlled, thereby resulting in advances in chemical sensing, molecular machines, and anticipated information storage. Although the introduction of a new term (i.e. TORC) into the chemical literature is not always useful, we believe that unifying the power and vision imparted by this class of bonding is deserving of terminology that embodies its promise.

Acknowledgements

This research was primarily supported by the National Science Foundation through the Center for Dynamics and Control of Materials: an NSF MRSEC under Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1720595. E.V.A. also gratefully acknowledges key financial support from the DARPA Fold-F(x) program (N66001-14-2-4051), the National Institutes of Health (1R01EB022025-01A1), and the Welch Regents Chair (F-0046).

Biography

James F. Reuther (left) received his BS in chemistry at Virginia Tech in 2010 and his PhD in polymer chemistry from North Carolina State University in 2014 under the direction of Bruce M. Novak. He finished his postdoctoral research with Prof. Eric V. Anslyn at the University of Texas at Austin in 2018 and joined the University of Massachusetts Lowell as an Assistant Professor of Polymer Chemistry with research focusing on the development of dynamically cross-linked nanocomposites and chiral materials synthesis.

Samuel D. Dahlhauser (middle) received his BS in chemistry at Sewanee: The University of the South in 2014. He spent the following year at the National Cancer Institute working with Dr. John Schneekloth, developing small-molecule inhibitors of Ubc9. Currently, he is pursuing his PhD with Prof. Eric V. Anslyn at the University of Texas at Austin. His research interests include sequence-defined polymers and their utilization in dynamic combinatorial libraries, and dynamic materials for the decontamination of nerve agents.

Eric V. Anslyn (right) received his BS from the California State University Northridge in 1982, and his PhD from Caltech under the supervision of Dr. Robert Grubbs in 1987. He was then an NSF postdoctoral fellow with Prof. Ronald Breslow at Columbia University, and started his independent career at University of Texas at Austin in 1989. He is a physical organic chemist at heart, and applies the principles of this field to mechanistic analysis, chemical sensing, and more recently complex chemical assembly.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

James F. Reuther, Department of Chemistry, University of Texas at Austin Austin, TX (USA); Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA (USA).

Samuel D. Dahlhauser, Department of Chemistry, University of Texas at Austin Austin, TX (USA)

Eric V. Anslyn, Department of Chemistry, University of Texas at Austin Austin, TX (USA).

References

- [1].Xia T, SantaLucia J Jr., Burkard ME, Kierzek R, Schroeder SJ, Jiao X, Cox C, Turner DH, Biochemistry 1998, 37, 14719–14735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lundeen JS, Sutherland B, Patel A, Stewart C, Bamber C, Nature 2011, 474, 188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Barany G, Merrifield RB, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1977, 99, 7363–7365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Albericio F, Biopolymers 2000, 55, 123–139; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Isidro-Llobet A, Álvarez M, Albericio F, Chem. Rev 2009, 109, 2455–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wong C-H, Ye X-S, Zhang Z, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 7137–7138. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wang C-C, Lee J-C, Luo S-Y, Kulkarni SS, Huang Y-W, Lee C-C, Chang K-L, Hung S-C, Nature 2007, 446, 896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Baran PS, Richter JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 7450–7451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Zeng F, Zimmerman SC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 5326–5327; [Google Scholar]; b) Antoni P, Robb MJ, Campos L, Montanez M, Hult A, Malmstrçm E, Malkoch M, Hawker CJ, Macromolecules 2010, 43, 6625–6631. [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Liu CF, Tam JP, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 6584–6588; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dawson P, Muir T, Clark-Lewis I, Kent S, Science 1994, 266, 776–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Komon ZJA, Diamond GM, Leclerc MK, Murphy V, Okazaki M, Bazan GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 15280–15285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Iha RK, Wooley KL, Nystrçm AM, Burke DJ, Kade MJ, Hawker CJ, Chem. Rev 2009, 109, 5620–5686; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tunca U, J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2014, 52, 3147–3165; [Google Scholar]; c) Campos LM, Killops KL, Sakai R, Paulusse JMJ, Damiron D, Drockenmuller E, Messmore BW, Hawker CJ, Macromolecules 2008, 41, 7063–7070. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mahal LK, Yarema KJ, Bertozzi CR, Science 1997, 276, 1125–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Willems LI, van der Linden WA, Li N, Li K-Y, Liu N, Hoogendoorn S, van der Marel GA, Florea BI, Over-kleeft HS, Acc. Chem. Res 2011, 44, 718–729; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 6974–6998; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2009, 121, 7108–7133; [Google Scholar]; c) Lim RKV, Lin Q, Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 1589–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Wong C-H, Zimmerman SC, Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 1679–1695; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Corbin PS, Lawless LJ, Li Z, Ma Y, Witmer MJ, Zimmerman SC, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 5099–5104; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Burd C, Weck M, Macromolecules 2005, 38, 7225–7230; [Google Scholar]; d) Hu X-Y, Xiao T, Lin C, Huang F, Wang L, Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 2041–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Jin Y, Yu C, Denman RJ, Zhang W, Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 6634–6654; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rowan SJ, Cantrill SJ, Cousins GRL, Sanders JKM, Stoddart JF, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2002, 41, 898–952; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2002, 114, 938–993. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yang Y, Urban MW, Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 7446–7467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Goral V, Nelen MI, Eliseev AV, Lehn J-M, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 1347–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jo HH, Lin C-Y, Anslyn EV, Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 2212–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wilson A, Gasparini G, Matile S, Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 1948–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Seifert HM, Ramirez Trejo K, Anslyn EV, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 10916–10924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pérez-Fuertes Y, Kelly AM, Johnson AL, Arimori S, Bull SD, James TD, Org. Lett 2006, 8, 609–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chapin BM, Metola P, Lynch VM, Stanton JF, James TD, Anslyn EV, J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 8319–8330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Meadows MK, Roesner EK, Lynch VM, James TD, Anslyn EV, Org. Lett 2017, 19, 3179–3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Bracchi ME, Fulton DA, Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 11052–11055; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sarma RJ, Otto S, Nitschke JR, Chem. Eur. J 2007, 13, 9542–9546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].a) Rodriguez-Docampo Z, Otto S, Chem. Commun 2008, 5301–5303; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Escalante AM, Orrillo AG, Furlan RLE, J. Comb. Chem 2010, 12, 410–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gehin C, Montenegro J, Bang E-K, Cajaraville A, Takayama S, Hirose H, Futaki S, Matile S, Riezman H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 9295–9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].a) Zhang K-D, Sakai N, Matile S, Org. Biomol. Chem 2015, 13, 8687–8694; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lascano S, Zhang K-D, Wehlauch R, Gademann K, Sakai N, Matile S, Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 4720–4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rocard L, Berezin A, Leo FD, Bonifazi D, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 15588; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2015, 127, 15808. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wulff G, Lauer M, Bohnke H, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1984, 23, 741–742; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 1984, 96, 714–716. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ye Z, Yufang X, Anslyn EV, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2013, 5017–5021. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hofmeier H, Schubert US, Chem. Soc. Rev 2004, 33, 373–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lehn JM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1988, 27, 89–112; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 1988, 100, 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hutin M, Bernardinelli G, Nitschke JR, Chem. Eur. J 2008, 14, 4585–4593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Içli B, Christinat N, Tçnnemann J, Schüttler C, Scopelliti R, Severin K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3154–3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Okochi KD, Jin Y, Zhang W, Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 4418–4420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Okochi KD, Han GS, Aldridge IM, Liu Y, Zhang W, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 4296–4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang K-D, Matile S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 8980–8983; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2015, 127, 9108–9111. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bravin C, Badetti E, Scaramuzzo FA, Licini G, Zonta C, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 6456–6460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Roberts DA, Pilgrim BS, Nitschke JR, Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 626–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Roberts DA, Pilgrim BS, Sirvinskaite G, Ronson TK, Nitschke JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9616–9623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Moulin E, Cormos G, Giuseppone N, Chem. Soc. Rev 2012, 41, 1031–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Escalante AM, Orrillo AG, Cabezudo I, Furlan RLE, Org. Lett 2012, 14, 5816–5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dragna JM, Pescitelli G, Tran L, Lynch VM, Anslyn EV, Di Bari L, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 4398–4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jo HH, Gao X, You L, Anslyn EV, Krische MJ, Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 6747–6753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Henning A, Hagihara S, Matile S, Chirality 2009, 21, 826–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].a) Ronson TK, Meng W, Nitschke JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9698–9707; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Grommet AB, Nitschke JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 2176–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zhang D, Ronson TK, Mosquera J, Martinez A, Nitschke JR, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 3717–3721; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2018, 130, 3779–3783. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bruns CJ, Stoddart JF, Nature of the Mechanical Bond: From Molecules to Machines, Wiley, Hoboken, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [49].von Delius M, Geertsema EM, Leigh DA, Nat. Chem 2010, 2, 96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].von Delius M, Geertsema EM, Leigh DA, Tang D-TD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 16134–16145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Barrell MJ, Campana AG, von Delius M, Geertsema EM, Leigh DA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 285–290; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2011, 123, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Campaña AG, Carlone A, Chen K, Dryden DTF, Leigh DA, Lewandowska U, Mullen KM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 5480–5483; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2012, 124, 5576–5579. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Martin CJ, Lee ATL, Adams RW, Leigh DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 11998–12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Beves JE, Blanco V, Blight BA, Carrillo R, D’Souza DM, Howgego D, Leigh DA, Slawin AMZ, Symes MD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 2094–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Campaña AG, Leigh DA, Lewandowska U, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 8639–8645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kassem S, Lee ATL, Leigh DA, Markevicius A, Solà J, Nat. Chem 2016, 8, 138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Erbas-Cakmak S, Fielden SDP, Karaca U, Leigh DA, McTernan CT, Tetlow DJ, Wilson MR, Science 2017, 358, 340–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].a) Wilson MR, Solà J, Carlone A, Goldup SM, Lebrasseur N, Leigh DA, Nature 2016, 534, 235; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kassem S, Lee ATL, Leigh DA, Marcos V, Palmer LI, Pisano S, Nature 2017, 549, 374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ding S-Y, Wang W, Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 548–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Zeng Y, Zou R, Luo Z, Zhang H, Yao X, Ma X, Zou R, Zhao Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1020–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Liang R-R, Xu S-Q, Pang Z-F, Qi Q-Y, Zhao X, Chem. Commun 2018, 54, 880–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Thakur VK, Kessler MR, Polymer 2015, 69, 369–383. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Deng G, Li F, Yu H, Liu F, Liu C, Sun W, Jiang H, Chen Y, ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Yu F, Cao X, Du J, Wang G, Chen X, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 24023–24031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Jackson AW, Fulton DA, Macromolecules 2012, 45, 2699–2708. [Google Scholar]

- [66].a) von Kiedrowski G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1986, 25, 932–935; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 1986, 98, 932–934; [Google Scholar]; b) Sievers D, von Kiedrowski G, Nature 1994, 369, 221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].a) Kosikova T, Philp D, Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 7274–7305; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sadownik JW, Mattia E, Nowak P, Otto S, Nat. Chem 2016, 8, 264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Liu Y-L, Chuo T-W, Polym. Chem 2013, 4, 2194–2205. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Discekici EH, St. Amant AH, Nguyen SN, Lee I-H, Hawker CJ, Read de Alaniz J, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 5009–5013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Yoshimura Y, Fujimoto K, Org. Lett 2008, 10, 3227–3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Tetsuya D, Hayato K, Keiji M, Hiromu K, Hiroyuki A, Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 10533–10538.27299696 [Google Scholar]

- [72].Marschner DE, Frisch H, Offenloch JT, Tuten BT, Becer CR, Walther A, Goldmann AS, Tzvetkova P, Barner-Kowollik C, Macromolecules 2018, 51, 3802–3807. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Claus TK, Telitel S, Welle A, Bastmeyer M, Vogt AP, Delaittre G, Barner-Kowollik C, Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 1599–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Frisch H, Marschner DE, Goldmann AS, Barner-Kowollik C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 2036–2045; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2018, 130, 2054–2064. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Ulman M, Grubbs RH, Organometallics 1998, 17, 2484–2489. [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chidchob P, Sleiman HF, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 46, 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Reuther JF, Dees JL, Kolesnichenko IV, Hernandez ET, Ukraintsev DV, Guduru R, Whiteley M, Anslyn EV, Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Reuther JF, Goodrich AC, Escamilla PR, Lu TA, Del Rio V, Davies BW, Anslyn EV, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 3768–3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Hernandez ET, Escamilla PR, Kwon S-Y, Partridge J, McVeigh M, Rivera S, Reuther JF, Anslyn EV, New J. Chem 2018, 42, 8577–8582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Hernandez ET, Kolesnichenko IV, Reuther JF, Anslyn EV, New J Chem. 2017, 41, 126–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]