Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to analyze the association between the types of physical activity (PA) and the level of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in Korean adolescents.

Methods

This study analyzed data from the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS) for, 2020–2021. The dependent variable was the level of generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7). The GAD-7 scores were divided into four levels: normal, mild, moderate, and severe. The independent variables were moderate PA, vigorous PA, and strength exercises. Sex, school grade, body mass index, stress, depression, suicidal thoughts, violent victimization, drinking, smoking, substance abuse, sleep satisfaction, and sedentary time were selected as confounding variables.

Results

The independent variable and all confounding variables showed significant differences with the level of GAD-7 (all p < .001). After adjusting for all confounding variables, we observed a 1.062 elevation in mild anxiety disorders, a 1.147 increase in moderate anxiety disorders, and a 1.218 increased incidence of severe anxiety disorders in the absence of vigorous PA. In the absence of strength exercises, there was a 1.057 elevation in mild anxiety disorders, a 1.110 increase in moderate anxiety disorders, and a 1.351 increased incidence of severe anxiety disorders. However, in the case of moderate PA, after adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association with GAD-7 levels.

Conclusion

To prevent anxiety disorders among Korean adolescents, the type of PA should be considered. Vigorous PA or strength exercises may help prevent GAD in Korean adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescents, anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder-7, physical activity, strength exercise

Introduction

False self-evaluation and mental confusion often occur during adolescence. 1 As a result, adolescents complain of temporary anxiety disorders. In severe cases, they experience generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). 2 This is a mental illness that causes not only extensive and excessive anxiety symptoms, but also various physical symptoms, such as fatigue, muscle tension, and concentration loss.3,4 According to the previous study, 12.3% of Korean adolescents are classified as having a moderate to severe level of GAD in 2021. 5

Early detection and prevention of GAD is difficult because one is not properly aware of one's condition.6,7 Moreover, GAD can lead to other mental illnesses, such as panic disorders or depression. 8 Particularly, GAD is associated with low self-esteem and sociopsychological problems in adolescents. 9

Previous studies have shown that factors such as sex, economic status, and grades, as well as health-related behavioral factors such as drinking, smoking, physical activity (PA), and stress affect the level of GAD in adolescents.10–13 Accordingly, the management of risk factors affecting GAD in adolescents may help prevent it. However, previous studies did not analyze the relationship between PA and GAD, considering the reported risk factors. Instead, they primarily presented factors that may affect GAD.10–13 We have previously reported that an increase in sedentary time increased the odds ratio (OR) for the prevalence of GAD. 14 Considering various confounding variables, an hourly increase in total sedentary time increased the likelihood of belonging to the severe GAD group by 1.045 times. However, regular PA did not show a significant association with GAD.

Contrary to our findings, regular PA, including exercise, is known to prevent and reduce the prevalence of GAD.15,16 The secretion of neurotransmitters, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), dopamine, and serotonin due to PA not only relieves stress, but also helps relieve symptoms of mental diseases, such as depression.17–19 Moreover, both aerobic and muscle exercises have been reported to help prevent anxiety disorders. 20 Kim and Shin reported a significant negative correlation between GAD scores and high-intensity PA and, similarly, a significant negative correlation between GAD scores and muscle exercise. 13 However, the previous study conducted a regression analysis using GAD scores. Therefore, the effect of PA on GAD in adolescents has not yet been fully elucidated.

To date, previous studies on the factors affecting GAD in Korean adolescents have not considered the confounding factors affecting GAD.12,13 Only the fragmentary results are presented. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the effect of implementation of PA according to the type of PA on the risk of GAD using the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS) which is a large-scale national statistical study.

Methods

Procedure of data collection

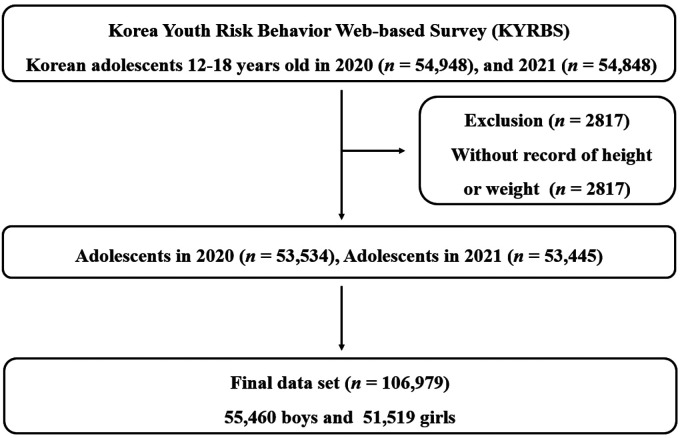

This study utilized the 16–17th KYRBS conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). The KYRBS is an anonymous online survey conducted from 2005 to understand the health behavior of Korean adolescents (aged 12–18 years). The KYRBS investigates adolescents’ socioeconomic conditions, drinking, smoking, substance abuse, dietary behavior, weight control efforts, PA, and mental health. It is a government-approved statistical survey (approval number 11758). This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations provided by the Institutional Review Board of the KDCA. Participants are selected using a stratified multistage probability sampling method. A total of 117,351 students from 800 schools (400 middle and 400 high schools) were possible participants. All participants have submitted written informed consent and detailed information regarding the survey is available related homepage (https://www.kdca.go.kr/yhs/). The target number of participants in the 2020 survey was 57,925, of which 54,948 responded (94.9% response rate), and the 2021 survey had 59,426 responses out of 54,848 (response rate 92.9%). They anonymously completed self-administered survey using computers at school. The 16th KYRBS period lasted from 3 August to 13 November 2020, and the 17th KYRBS was performed from 30 August to 11 November 2021. In this study, all completed survey responses were included in the analysis, and data that did not include the necessary height and weight information for calculating body mass index (BMI), one of the variables, were excluded from the analysis. A detailed flow diagram of the participants in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow diagram of the study participants.

Measurement variables

Independent variable

The independent variables were PA by type. To distinguish PA by type, we used a questionnaire on moderate PA, vigorous PA, and strength exercise. The definitions of PA and strength exercise were based on the American College of Sports Medicine's (ACSM) PA guidelines. 21 ACSM recommends moderate-intensity PA for at least 30 min per session, 5 days a week, and vigorous-intensity PA for at least 20 min per session, 3 or more days a week. Strength exercise is recommended two–three times per week. The question determining moderate PA was, “In the last seven days, how many days did you engage in PA (regardless of the type) where your heart rate increased, or you experienced heavy breathing for more than 60 min a day?”. Moderate PA was classified as “yes” if it was performed for more than 5 days a week, and otherwise considered “no.” The question about vigorous PA was, “In the last seven days, how many days have you been sweating or out of breath for more than 20 min?”. Vigorous PA was classified as “yes” if it was performed for more than 3 days a week, and otherwise considered “no.” The question about strength exercise was, “In the last 7 days, how many days have you done muscle strength exercises (muscle strengthening exercises) such as push-ups, sit-ups, lifting weights, dumbbells, pull-ups, and parallel bars?”. Strength exercise was classified as “yes” if it was performed for more than 3 days a week, and otherwise considered “no.”

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was general anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7). It is a used evaluation tool that can effectively judge GADs for adolescents. A previous study for Finnish adolescents reported that GAD-7 reliability is 0.89 (Cronbach's α). 22 It is a self-reported measurement tool that evaluates seven items related to anxiety. We used the Korean version of the GAD-7. The score of each question consists of 0 to 3 points. In each of the seven questions, the total score of GAD-7 is up to 21 points, The total scores of GAD-7 were classified into the following four levels: 0–4 points are normal, 5–9 points are mild, 10–14 points are moderate, and 15–21 points are evaluated as severe anxiety disorders. 23

Confounding variables

The following factors were selected as confounding variables that could affect GAD. Sex, school grade, BMI, stress, depression, suicidal thoughts, substance abuse, violent victimization, drinking, smoking, sleep satisfaction, and sedentary time were used for the analysis. Among the confounding variables, sex was used without reconstruction. School grade was divided into middle and high school. Students in grades 7 to 9 were categorized as middle school, and students in grades 10 to 12 were classified as high school. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated using height and weight. The question evaluating stress was, “How much stress do you usually feel?”. The five-step answers to stress were reconstructed as “yes” and “no.” The question about depression was, “Have you ever been sad or desperate enough to stop your routine for more than two weeks in the past 12 months?”. The question about suicidal thoughts was, “Have you seriously considered suicide in the last 12 months?”. The question concerning substance abuse was, “Except for therapeutic purposes, have you ever used any medications or substances habitually?”. The answers to depression, suicidal thoughts, and substance abuse were “yes” and “no.” As for the question of violent victimization, “Have you been treated in a hospital for violence (physical assault, intimidation, bullying, etc.) by friends, seniors, or adults in the last 12 months?”. The response was re-divided into “no” for 0 and “yes” for more than one-time response. The question about drinking was, “In the last 30 days, how many days did you drink more than one cup?” and the question about smoking was, “In the last 30 days, how many days did you usually smoke one or more cigarettes?”. The responses to these questions were reconstructed as “yes” and “no.” In case of sleep satisfaction, the question was, “Do you think the time you slept in the last seven days is enough to recover from fatigue?”. The answers were reconstructed as “yes” and “no.” The sedentary time was the sum of the sedentary time for learning and other sedentary times. Sedentary time for learning included school and academic classes, watching TV or using a computer to do homework or study, and educational broadcasting. Other sedentary times included watching TV, playing games, using the Internet, chatting, and sitting on the go. The following formula was used in this study to calculate the average sedentary time for 7 days: ([weekdays sedentary time × 5] + [weekends sedentary time × 2])/7. The calculated sedentary time was divided into two categorical variables based on 8 h.

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed using the SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Amonk, N.Y., USA). The data were applied strata, cluster, weight, and finite population correction. The chi-squared test (Rao-Scott) was conducted to investigate the differences with subjects’ confounding variables and PAs (moderate PA, vigorous PA, and strength exercise) according to the level of anxiety disorder. The complex samples logistic regression analysis was conducted to analyze the association between each PA and level of anxiety disorder. The OR and 95% confidence interval were calculated for level of anxiety disorder according to type of PAs. The level of statistical significance (α) was set to 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the Korean adolescents based on level of anxiety disorder

The total number of adolescents in this study was 106,979. According to the level of anxiety disorder, 70,721 were normal, 23,949 were mild, 8322 were moderate, and 3987 were severe. Table 1 shows the characteristics of Korean adolescents according to level of GAD-7. Sex and school grade showed significant differences in GAD-7 levels (all p < 0.001). BMI also showed significant differences according to GAD-7 levels (p < 0.016). All confounding variables showed significant differences with GAD-7 levels (all p < 0.001). Table 2 shows the detailed chi-square test results between the confounding variables and GAD-7 scores.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Korean adolescents based on level of anxiety disorder.

| Normal (N = 70,721) | Mild (N = 23,949) | Moderate (N = 8322) | Severe (N = 3987) | Total (N = 106,979) | x² (p) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 40,254 (72.0) | 10,619 (19.4) | 3207 (6.0) | 1380 (2.6) | 55,460 (100.0) | 585.202 |

| Female | 30,467 (59.1) | 13,330 (25.9) | 5115 (10.0) | 2607 (5.0) | 51,519 (100.0) | <.001 |

| School grade | ||||||

| Middle school (7th-9th) | 39,079 (67.7) | 12,266 (21.4) | 4260 (7.5) | 2006 (3.4) | 57,611 (100.0) | 38.923 |

| High school (10th-12th) | 31,642 (63.9) | 11,683 (23.7) | 4062 (8.4) | 1981 (4.0) | 49,368 (100.0) | <.001 |

| BMI | ||||||

| <23 | 48,671 (65.5) | 16,720 (22.8) | 5739 (7.9) | 2786 (3.7) | 73,916 (100.0) | 3.478 |

| 23≤ | 22,050 (66.4) | 7229 (22.0) | 2583 (8.0) | 1201 (3.7) | 33,063 (100.0) | .016 |

BMI: body mass index. Values are N (%). Percentage is weighted.

Table 2.

Differences in health risk behaviors based on level of anxiety disorder.

| Normal (N = 70,721) | Mild (N = 23,949) | Moderate (N = 8322) | Severe (N = 3987) | Total (N = 106,979) | x² (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | ||||||

| No | 20,523 (94.0) | 1084 (5.1) | 151 (0.7) | 62 (0.3) | 21,820 (100.0) | 3132.134 |

| Yes | 50,198 (58.7) | 22,865 (26.9) | 8171 (9.7) | 3925 (4.6) | 85,159 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Depression | ||||||

| No | 61,089 (76.6) | 14,109 (18.0) | 3188 (4.1) | 971 (1.2) | 79,357 (100.0) | 6322.235 |

| Yes | 9632 (34.7) | 9840 (35.7) | 5134 (18.8) | 3016 (10.8) | 27,622 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Suicidal thoughts | ||||||

| No | 67,652 (71.2) | 19,698 (21.0) | 5420 (5.9) | 1808 (1.9) | 94,578 (100.0) | 5062.275 |

| Yes | 3069 (24.6) | 4251 (34.4) | 2902 (23.7) | 2179 (17.4) | 12,401 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Violent victimization | ||||||

| No | 70,139 (66.1) | 23,623 (22.5) | 8115 (7.8) | 3796 (3.6) | 105,673 (100.0) | 200.408 |

| Yes | 582 (45.7) | 326 (23.9) | 207 (15.6) | 191 (14.8) | 1306 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Drinking | ||||||

| No | 65,828 (66.6) | 21,642 (22.2) | 7382 (7.7) | 3441 (3.5) | 98,293 (100.0) | 140.181 |

| Yes | 4893 (56.5) | 2307 (26.4) | 940 (10.9) | 546 (6.2) | 8686 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| No | 68,118 (66.2) | 22,751 (22.4) | 7811 (7.8) | 3675 (3.6) | 102,355 (100.0) | 80.483 |

| Yes | 2603 (56.4) | 1198 (25.9) | 511 (11.0) | 312 (6.7) | 4624 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Substance abuse | ||||||

| No | 70,453 (66.0) | 23,754 (22.5) | 8200 (7.9) | 3849 (3.6) | 106,256 (100.0) | 236.264 |

| Yes | 268 (35.9) | 195 (27.8) | 122 (15.6) | 138 (20.7) | 723 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Sleep satisfaction | ||||||

| No | 47,528 (60.7) | 19,754 (25.4) | 7250 (9.4) | 3559 (4.5) | 78,091 (100.0) | 1112.109 |

| Yes | 23,193 (79.8) | 4195 (14.8) | 1072 (3.9) | 428 (1.5) | 28,888 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Sedentary time | ||||||

| < 8 hour | 23,010 (70.3) | 6509 (20.0) | 2126 (6.6) | 1046 (3.1) | 32,691 (100.0) | 122.855 |

| 8 hour ≤ | 47,711 (63.9) | 17,440 (23.6) | 6196 (8.5) | 2941 (4.0) | 74,288 (100.0) | <.001 |

Values are N (%). Percentage is weighted.

Differences in odds of anxiety disorder level according to physical activity type

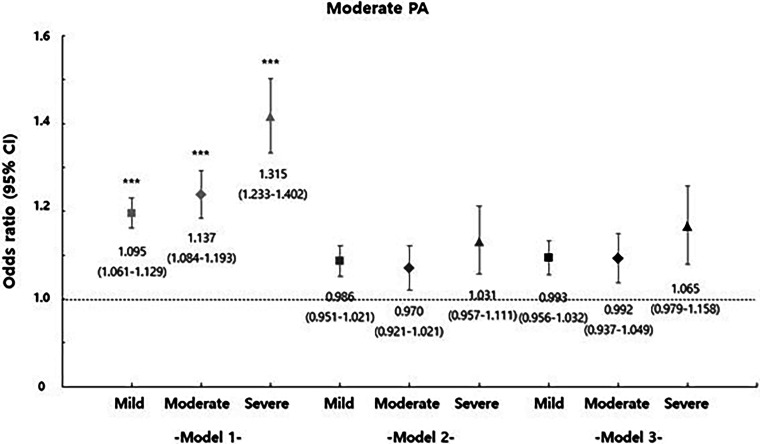

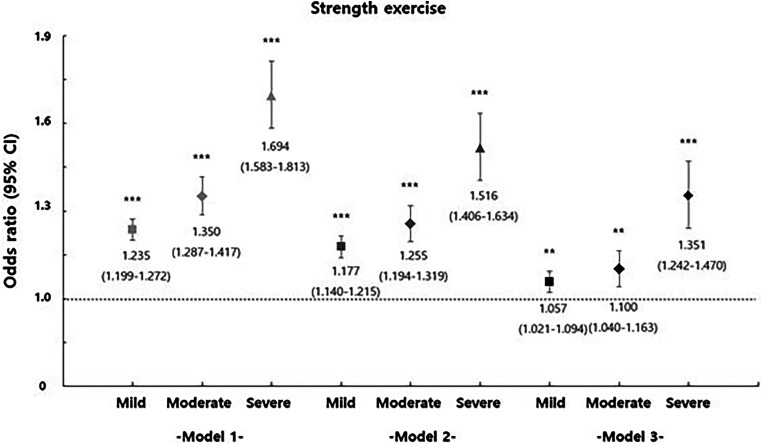

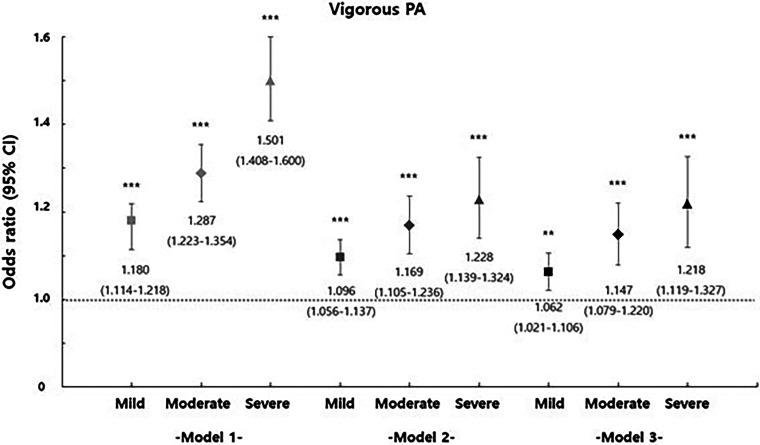

Figures 2–4 show the possibility of anxiety disorders when PA is not performed. Model 1 was not adjusted, Model 2 was adjusted for sedentary time, vigorous PA, and strength exercise, and Model 3 was adjusted for sex, school grade, BMI, stress, depression, suicidal thoughts, violent victimization, drinking, smoking, substance abuse, sleep satisfaction, sedentary time, vigorous PA, and strength exercise. Without the application of confounding variables (Model 1), the absence of each PA significantly increased the odds of anxiety disorder by 1.095–1.694 times based to normal levels (all p < 0.001). However, there was no increased risk of any GAD if moderate PA was not performed by applying all confounding variables (Model 3). When vigorous PA is not performed, the risk of mild GAD increased by 1.062 times (p < 0.01), the risk of moderate levels increased by 1.147 times (p < 0.001), and the risk of severe levels increased by 1.218 times (p < 0.001) in Model 3. When strength exercises are not carried out, in Model 3, the risk of mild levels increased by 1.057 times (p < 0.01), the risk of moderate levels increased by 1.100 times (p < 0.01), and the risk of severe levels increased by 1.351 times (p < 0.001) in Model 3.

Figure 2.

Logistic regression analysis to level of anxiety disorder according to moderated PA. Model 1 was not adjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for sedentary time, vigorous PA, and strength exercise; Model 3 was adjusted for sex, school grade, BMI, stress, depression, suicidal thoughts, violent victimization, drinking, smoking, substance abuse, sleep satisfaction, sedentary time, vigorous PA, and strength exercise. PA: physical activity; BMI: body mass index.

Figure 4.

Logistic regression analysis to level of anxiety according to strength exercise. Model 1 was not adjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for sedentary time, moderate PA, and vigorous PA; Model 3 was adjusted for sex, school grade, BMI, stress, depression, suicidal thoughts, violent victimization, drinking, smoking, substance abuse, sleep satisfaction, sedentary time, moderate PA, and vigorous PA. PA: physical activity; BMI: body mass index.

Figure 3.

Logistic regression analysis to level of anxiety disorder according to vigorous PA. Model 1 was not adjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for sedentary time, moderate PA, and strength exercise; Model 3 was adjusted for sex, school grade, BMI, stress, depression, suicidal thoughts, violent victimization, drinking, smoking, substance abuse, sleep satisfaction, sedentary time, moderate PA, and strength exercise. PA: physical activity; BMI: body mass index.

Discussion

The aim of this study is to analyze the differences in the risk levels of GAD based on the types of PA and to provide foundational data for the prevention and reduction of GAD. The level of GAD was analyzed using the GAD-7, which divided anxiety disorders into normal, mild, moderate, and severe categories. The GAD-7 scores of 106,979 Korean adolescents were analyzed. The proportion of patients with severe, moderate, mild, and normal GAD was 3.73%, 7.78%, 22.38%, and 66.10%, respectively.

In our previous study, considering the confounding variables related to GAD, we observed that as total sedentary time increased by 1 h, the OR for severe GAD-7 levels increased by 1.045 times. As in previous studies, it is clear that an increase in sedentary behavior is significantly associated with GAD.13–16 However, unlike sedentary time, regular PA was not significantly related to GAD levels in our previous study. Previous studies have shown that regular PA or moderate levels of exercise help alleviate anxiety disorders13–16; however, our study did not reveal this. A previous study reported a significant negative correlation between GAD-7 scores and PA through multiple regression analysis; vigorous PA and strength exercises were more effective in preventing GAD than mild PA. 13 However, they only divided PA into three types and did not provide specific information such as intensity, time, and frequency. Furthermore, while dividing the GAD-7 by level to determine the presence or absence of anxiety disorders can help determine the relationship between anxiety disorders and each factor, they simply performed a multiple regression analysis between the GAD-7 score and each factor.

Considering the results of previous studies showing that the higher the intensity of PA, the lower the probability of developing anxiety disorders, it is necessary to confirm the relationship between PA and GAD through various methods such as intensity and type of PA. Our Study showed that the absence of moderate PA did not show a significant relationship with GAD levels; however, the absence of vigorous PA and strength exercises significantly increased GAD-7 levels. In particular, even when considering all confounding variables, vigorous PA and the absence of strength exercises increased the GAD-7 OR at all levels.

Several studies have reported that high levels of PA or aerobic exercise can help relieve anxiety disorders.24–26 Similarly, strength exercises have been reported to help relieve anxiety disorders and depression.20,27 A previous study reported relief from anxiety disorders through strength exercises. 20 They conducted eight types of strength exercises for young adults aged 18–40 years over an 8-week period. Strength exercises have been reported to significantly reduce anxiety disorders (mean difference = − 7.89, p = -0.001). However, it has not been fully elucidated whether muscle exercise helps relieve anxiety disorders compared with aerobic exercise in adolescents.28,29 As with aerobic exercise, strength training has been reported to increase the secretion of the neurotransmitters BDNF, dopamine, and serotonin.18,19 No specific mechanisms for PA, including strength exercises, have been identified to alleviate anxiety disorders.30,31 However, increased secretion of these substances through PA helps reduce anxiety disorders, including stress.32,33 Our results are similar to those of previous studies.13,27 Nonetheless, they are valuable because they provide specific information on PA. In summary, considering the various variables affecting GAD, moderate PA of more than 60 min per week does not affect GAD. However, vigorous PA and strength exercises of more than 20 min, three times per week, can affect GAD, and strength exercises can be more effective than vigorous PA.

This study is meaningful because it analyzed the level of GAD in Korean adolescents according to the type of PA using the KYRBS. Because it is a national statistical dataset and contains vast contents related to the health of adolescents, it was possible to analyze it by considering various confounding variables that may affect anxiety disorders. However, this study has several limitations. Since the KYRBS is an online self-report questionnaire (anonymous survey) completed by adolescents themselves, it is possible that some factors (smoking, drinking, violence, suicide, etc.) did not accurately reflect their behavioral characteristics. Furthermore, anxiety levels were classified as GAD-7 scores; however, it may be difficult to evaluate all anxiety symptoms as GAD-7 in this study. Finally, because this was this study is a cross-sectional study, it was not possible to clearly explain the effect of each type of PA on anxiety disorders. Therefore, it will be necessary to comparatively analyze the effects of various types of PA programs on anxiety disorders through future intervention studies in the future.

Conclusion

Considering the various variables affecting GAD, the OR for the level of GAD increased significantly according to the type of PA. Specifically, if moderate PA was not performed, the OR of GAD did not increase significantly. However, if vigorous PA and strength exercises were not performed, the OR of GAD increased significantly. Engaging in vigorous PA or strength exercises for at least three sessions per week, each lasting more than 20 min, could potentially contribute to the prevention of GAD among Korean adolescents.

Acknowledgment

All authors would like to thank the KDCA, which provided the data.

Footnotes

Contributorship: All authors jointly conceived the study. KL collected and analyzed the data. KL and JS provided input into the study design and data analysis. KL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JS reviewed and edited the manuscript. JS integrated the feedback into the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations provided by the Institutional Review Board of the KDCA.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor: KL.

ORCID iD: Kihyuk Lee https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6717-7087

References

- 1.You S, Shin K, AY K. Body image, self-esteem, and depression in Korean adolescents. Child Indic Res 2017; 10: 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HT, Hyun MH. The mediating effect of cognitive emotion regulation strategy on the relationship between emotion malleability beliefs and depression, anxiety in individual with generalized anxiety tendency. KSSM 2019; 27: 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KH. Diagnosis and psychological assessment of generalized anxiety disorder. JKNA 2012; 51: 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American psychiatric association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Reports on the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey. 2021. https://www.kdca.go.kr/yhs/ (accessed 21 December 2023)

- 6.Achenbach TM. Implications of multiaxial empirically based assessment for behavior therapy with children. Behav Ther 1993; 24: 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsawh HJ, Chavira DA. Association of childhood anxiety disorders and quality of life in a primary care sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2016; 37: 269–276. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40: 1086–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen DT, Wright EP, Dedding C, et al. Low self-esteem and its association with anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation in Vietnamese secondary school students: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry 2019; 27: 698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JP, Randall CL. Anxiety and alcohol use disorders: comorbidity and treatment considerations. Alcohol res 2012; 34: 414–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim SJ. The associated factors with generalized anxiety disorder in Korean adolescents. Korean Public Health Res 2021; 47: 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woo KS, Ji Y, Lee HJ, et al. The association of anxiety severity with health risk behaviors in a large representative sample of Korean adolescents. Soa Chongsonyon Chongsin Uihak 2021; 32: 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim ML, Shin K. Exploring the major factors affecting generalized anxiety disorder in Korean adolescents: based on the 2021 Korea youth health behavior survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 9384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song H, Lee K. Increased risk of generalized anxiety disorder according to frequent sedentary times based on the 16th Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey. Children 2022; 9: 1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teychenne M, Costigan SA, Parker K, et al. The association between sedentary behaviour and risk of anxiety: a systematic review. BMC public Health 2015; 15: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. High sedentary behaviour and low physical activity are associated with anxiety and depression in Myanmar and Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhagen LA, Luijendijk MC, Korte-Bouws GA, et al. Dopamine and serotonin release in the nucleus accumbens during starvation-induced hyperactivity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2009; 19: 309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoladz JA, Pilc A. The effect of physical activity on the brain derived neurotrophic factor: from animal to human studies. J Physiol Pharmacol 2010; 61: 533–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heijnen S, Hommel B, Kibele A, et al. Neuromodulation of aerobic exercise—a review. Front Psychol 2016; 6: 1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon BR, McDowell CP, Lyons M, et al. Resistance exercise training for anxiety and worry symptoms among young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayles M. ACSM’s exercise testing and prescription. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiirikainen K, Haravuori H, Ranta K, et al. Psychometric properties of the 7-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Res 2019; 272: 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broman-Fulks JJ, Berman ME, Rabian BA, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on anxiety sensitivity. Behav Res Ther 2004; 42: 125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinsen EW. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression. Nord J Psychiatry 2008; 62: 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jayakody K, Gunadasa S, Hosker C. Exercise for anxiety disorders: systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.BS H, Raglin JS. State anxiety responses to acute resistance training and step aerobic exercise across 8-weeks of training. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2002; 42: 108–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rashidi M, Rashidypour A, Ghorbani R, et al. The comparison of aerobic and anaerobic exercise effects on depression and anxiety in students. Koomesh 2017; 19: 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- 29.da Costa TS, Seffrin A, de Castro Filho J, et al. Effects of aerobic and strength training on depression, anxiety, and health self-perception levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022; 26: 5601–5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dishman RK, Berthoud HR, Booth FW, et al. Neurobiology of exercise. Obesity 2006; 14: 345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cassilhas RC, Lee KS, Fernandes J, et al. Spatial memory is improved by aerobic and resistance exercise through divergent molecular mechanisms. Neuroscience 2012; 202: 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21: 33–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, et al. An examination of the anxiolytic effects of exercise for people with anxiety and stress-related disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2017; 249: 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]