Abstract

6-Pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase (6-PTPS) is a lyase involved in the synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin. In Plasmodium species where dihydroneopterin aldolase (DHNA) is absent, it acts in the folate biosynthetic pathway necessary for the growth and survival of the parasite. The 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase of Plasmodium falciparum (PfPTPS) has been identified as a potential antimalarial drug target. This study identified potential inhibitors of PfPTPS using molecular docking techniques. Molecular docking and virtual screening of 62 compounds including the control to the deposited Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure was carried out using AutoDock Vina in PyRx. Five of the compounds, N,N-dimethyl-N’-[4-oxo-6-(2,2,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)-3H-pteridin-2-yl]methanimidamide (140296439), 2-amino-6-[(1R)-3-cyclohexyl-1-hydroxypropyl]-3H-pteridin-4-one (140296495), 2-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)-8,9-dihydro-6H-pyrimido[2,1-b]pteridine-7,11-dione (144380406), 2-(dimethylamino)-6-[(2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)-hydroxymethyl]-3H-pteridin-4-one (135573878), and [1-acetyloxy-1-(2-methyl-4-oxo-3H-pteridin-6-yl)propan-2-yl] acetate (136075207), showed better binding affinity than the control ligand, biopterin (135449517), and were selected and screened. Three conformers of 140296439 with the binding energy of −7.2, −7.1, and −7.0 kcal/mol along with 140296495 were better than the control at −5.7 kcal/mol. In silico absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) studies predicted good pharmacokinetic properties of all the compounds while reporting a high risk of irritant toxicity in 140296439 and 144380406. The study highlights the five compounds, 140296439, 140296495, 144380406, 135573878 and 136075207, as potential inhibitors of PfPTPS and possible compounds for antimalarial drug development.

Keywords: Molecular docking, drug targets, antimalarial drugs, potential inhibitors, Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase

Introduction

Malaria is a life-threatening disease with a significant impact on the human genome as evidenced by the positive selection of protective genetic traits such as sickle cell trait and beta-thalassaemia.1,2 The disease recorded an alarming number of 241 million cases leading to 627 000 deaths in 2021. 3 Drugs that have been used against this disease over the years include aryl amino alcohol compounds, antifolates, artemisinin and its derivatives, and artemisinin combination therapies.4,5 Antifolates are a group of drugs that inhibit the action of folic acid and have been found to be effective against many pathogens and tumor cells.6,7 The pathway where this drug acts is the folate biosynthesis pathway is an important pathway essential for the survival of the parasites but absent in humans. Antifolates that were once effective against malaria have now lost efficacy due to point mutations developed by the parasite in the genes coding for the target enzymes, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS).8-10 Its peculiarity of only occurring in the parasite and not in humans makes it an important pathway to be targeted, thereby necessitating the need to identify and develop new strategies for treatment and alternative targets in the metabolic pathway that is crucial to overcoming drug resistance and the global burden of malaria.11-13 New targets of the folate biosynthetic pathway have been identified, one of which is dihydroneopterin aldolase (DHNA) which is responsible for the formation of HMDMP (6-Hydroxymethyldihydropterin). This enzyme is, however, absent in the malaria parasite, and the formation of HMDMP is catalyzed by PTPS III known as Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase (PfPTPS). 14 Conventional PTPS (PTPS-I) is essential for the biosynthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a crucial cofactor for several enzymes that play important roles such as aromatic amino acid hydroxylases, glycerol ether monooxygenases, and nitric oxide synthases. 15 The catalytic process of converting dihydroneopterin triphosphate (H2NTP) into HMDMP, which constitutes the second enzymatic stage in the biosynthesis of folic acid from guanosine triphosphate (GTP), is facilitated by the enzyme 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.14,15,17 Therefore, PTPS represents a potential target for antimalarial drugs, and inhibiting its activity in the parasite could impede the synthesis of folic acid resulting in reduced folate and DNA synthesis leading to the death of the parasite. 18

Research has revealed the crystal structure of PfPTPS, which consists of a homo hexameric enzyme composed of a dimer of trimers. 19 Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase has been found to be critical for the survival of the P falciparum parasite, as it plays a key role in providing the missing link in folate biosynthesis. 17 In silico techniques, such as virtual screening, can identify potential drug candidates targeting PfPTPS. 20 Such compounds would be a valuable contribution to current efforts in malaria control, which remains a significant global health burden. Various in silico techniques, including molecular dynamics simulations and virtual screening, have been proposed as effective means to identify and select relevant therapeutic targets, design compound libraries, and optimize high-affinity ligands. 21 The successful identification of compounds that target PfPTPS would represent a significant advancement in malaria control.

Methodology

Retrieval of sequence and structure

The amino acid sequence of PfPTPS was retrieved with the ID: C6KTB6 from Uniprot. 22 The sequence was saved to be used for further studies. The three-dimensional (3D) structure of PfPTPS was retrieved with the ID: 1Y13 the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

Determination of the physicochemical properties of Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase

These properties were calculated with the Expasy ProtParam 23 (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) prediction server. The properties calculated include the estimated half-life, aliphatic index, isoelectric point (pI), number of positive and negative residues, molecular weight, extinction coefficient, instability index (II), and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY).

Prediction of the secondary structure of Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase

The SOPMA web tool 24 was used to predict the secondary structure secondary of Pf PTPS.

Determination of Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase active site

The CASTp server 25 was used to determine the active site of the enzyme.

Ligand preparation for structure-based virtual screening

Ligands were selected from PubChem, 26 a database of chemical molecules. Chemical structures similar to biopterin, the co-crystalized ligand for PfPTPS were gotten from PubChem using the Tanimoto threshold of 85%. The Lipinski rule of 5 and the Veber rule were used to filter the results which yielded 106 conformers. To remove duplicated compounds, the Galaxy Europe platform’s Remove Duplicated Molecules program 27 was used reducing our results to 61 compounds. In addition to biopterin, the compounds totaled 62. Energy minimization was carried out using Open Babel in PyRx.27,28

Preparation of the 3D structure of PfPTPS and virtual screening

The structure cleaning and minimization were carried out using Chimera 1.16. 29 The screening was carried out using AutoDock Vina Wizard in PyRx. 28

Post-docking analysis

The Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021 was used to analyze the results from the docking process.

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties of results

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) studies estimate the pharmacokinetic properties, the toxicity risk, and the determination of a compound’s chance of becoming a drug. These properties were evaluated using the OSIRIS Property Explorer too. The properties evaluated include the logarithm of solubility (Log S), the octanol-water partition coefficient (cLogP), the topological polar surface area (TPSA), the drug-likeness, and the drug score. The mutagenicity, tumorigenicity, irritant risk, and reproductive toxicity were evaluated.

Results and Discussion

Physicochemical properties of Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase

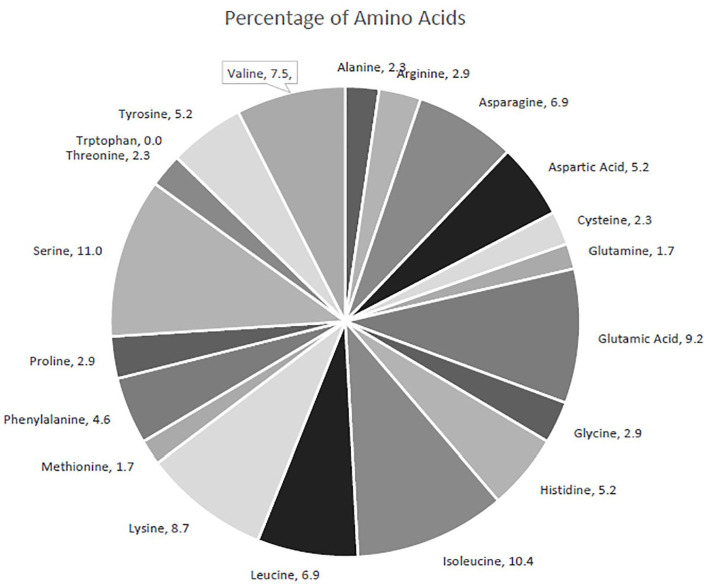

Table 1 shows the computed physicochemical properties of PfPTPS. The physicochemical parameters of a protein are determined by its composition. The enzyme, PfPTPS is made up of 173 amino acids (aa) and 2810 atoms. The most abundant amino acid residue is serine (11%), closely followed by isoleucine (10.4%) and then by glutamate (8.7%). The amino acid, tryptophan was absent in the enzyme. The amino acid composition is shown in Figure 1. The hydrophilic nature is influenced by the high number of hydrophilic residues (59.1%) compared with the hydrophobic residues (30.4%), and this prediction is supported by the negative GRAVY value of −0.364. 30 The number of negatively charged residues is 25 whereas positively charged residues numbered 20. The pI is 5.98, and the molecular weight of the protein is 20 060.82 Da (20.06 kDa). These properties are necessary for determining the area of gel where this enzyme can be identified. 31 The protein’s acidic nature is further shown by the pI at 5.98. The II is computed to be 46.44 classifying the protein as unstable. The aliphatic index of the enzyme is 91.73. A high aliphatic index indicates the thermostability of the enzyme over a wide temperature range. 32 This protein does not contain any Trp residues which indicates that it might result in a 10% error in the extinction coefficient. The extinction coefficient is 13 660 M−1 cm−1at 280 nm in water with an absorbance of 0.681 assuming all pairs of cysteine residues form cystines.

Table 1.

Computed physicochemical properties of PfPTPS.

| Number of amino acids | Molecular weight | pI | Instability index | Aliphatic index | GRAVY | Extinction coefficient | Hydrophilic residues | Hydrophobic residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 173 | 20 060.82 | 5.98 | 46.44 | 91.73 | −0.364 | 13 660 | 59.1% | 30.4% |

Abbreviations: GRAVY, grand average of hydropathicity; PfPTPS, Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.

Figure 1.

The percentage of amino acids present in PfPTPS. PfPTPS indicates Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.

Determination of the active site of Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase

The amino acid residues that were found in the active site are shown in Table 2. The active sites of 1Y13 consist of 23 amino acids. There were no cysteine residues found in the active site which is consistent with findings reported by a previous study. 14

Table 2.

The amino acid residues present in the active site of PfPTPS.

| Amino acid residues | |

|---|---|

| 1Y13 | SER13, ALA14, GLU15, SER17, VAL18, GLU19, SER48, LEU49, LYS50, ARG52, TYR154, GLU156, ILE157, SER158, SER160, SER162, PRO163, THR164, GLN165, LYS166, ILE168, HIS170, TYR172 |

Abbreviation: PfPTPS, Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.

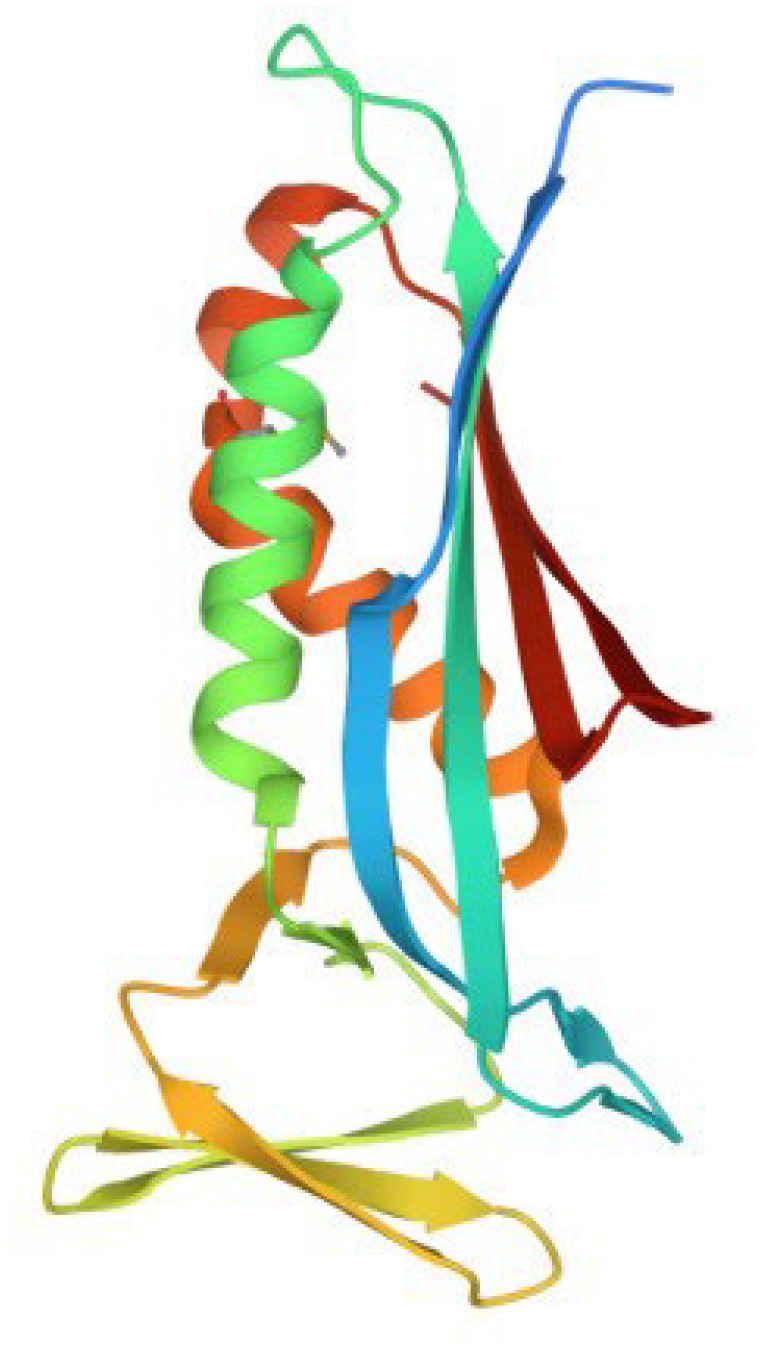

Prediction of Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase secondary structure

The type of motifs of secondary structures predicted for PfPTPS includes the alpha helix, the extended strand, the random coil, and the beta-turn. The highest percentage was recorded for the alpha helix (34.04%), closely followed by the extended strand (30.64%), random coil (29.48%), and beta-turn (5.78%). High percentages of alpha helix and extended strands are reported to play important roles in the compactness, folding, and stability of a protein (Figure 2). 33

Figure 2.

The 3D structure of Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase (PDB:1Y13_Chain A). PDB indicates Protein Data Bank.

Virtual screening analysis

The lower the negative value, the higher the ligand’s affinity for the protein. A total of 62 compounds, including biopterin, were blindly docked into PfPTPS, and 7 best hits were obtained and are shown in Table 3. The binding affinities of the top 7 hits were between −7.2 and −6.7 kcal/mol which was lower and therefore better than that of the co-crystallized ligand biopterin, with a binding affinity of −5.7 kcal/mol. Compound 140296439 had the lowest binding affinity of −7.2 kcal/mol signifying its potential to inhibit PfPTPS, thereby limiting the synthesis of folate and the activity of the parasite.

Table 3.

The structures and binding affinities of the best hits in comparison with the co-crystallized ligand, biopterin.

| S/N | Compound name and ID | 2D structures | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N,N-dimethyl-N’-[4-oxo-6-(2,2,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)-3H-pteridin-2-yl]methanimidamide (140296439, First Pose) |

|

−7.2 |

| 2 | N,N-dimethyl-N’-[4-oxo-6-(2,2,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)-3H-pteridin-2-yl]methanimidamide (140296439; Second Pose) |

|

−7.1 |

| 3 | N,N-dimethyl-N’-[4-oxo-6-(2,2,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)-3H-pteridin-2-yl]methanimidamide (140296439; Third Pose) |

|

−7.0 |

| 4 | 2-Amino-6-[(1R)-3-cyclohexyl-1-hydroxypropyl]-3H-pteridin-4-one (140296495) |

|

−6.8 |

| 5 | 2-(2,3-Dihydroxypropyl)-8,9-dihydro-6H-pyrimido[2,1-b]pteridine-7,11-dione (144380406) |

|

−6.8 |

| 6 | 2-(Dimethylamino)-6-[(2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)-hydroxymethyl]-3H-pteridin-4-one (135573878) |

|

−6.7 |

| 7 | [1-Acetyloxy-1-(2-methyl-4-oxo-3H-pteridin-6-yl)propan-2-yl] acetate (136075207) |

|

−6.7 |

| 8 | Biopterin (2-amino-6-[(1S,2R)-1,2-dihydroxypropyl]-3H-pteridin-4-one (135449517)) |

|

5.7 |

Abbreviation: 2D, two-dimensional.

Post-screening analysis

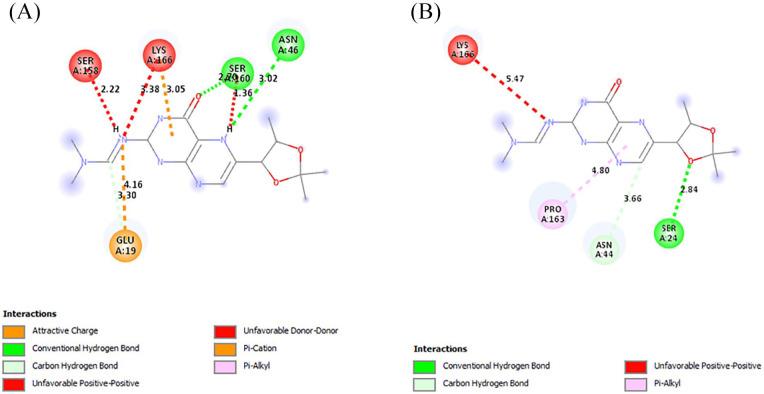

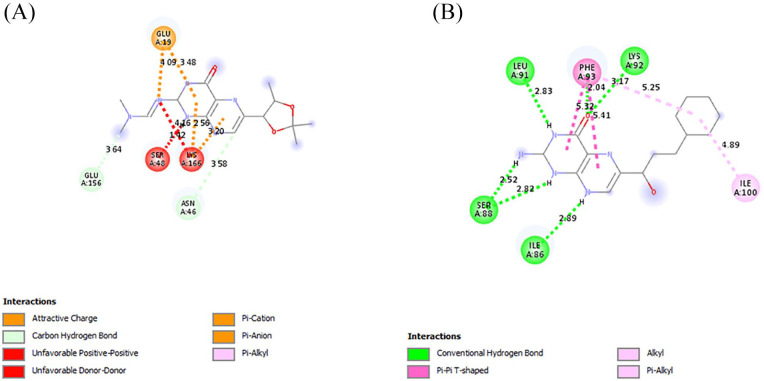

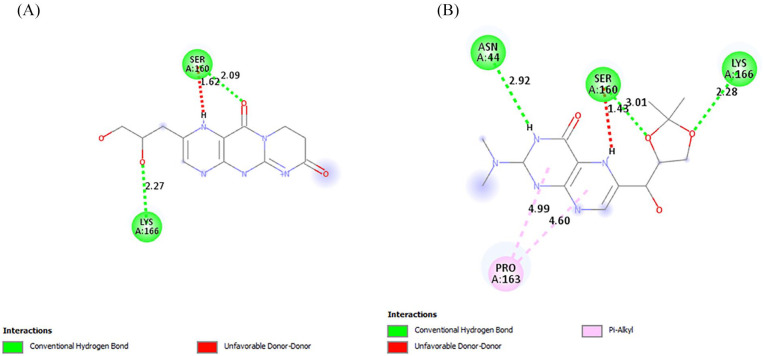

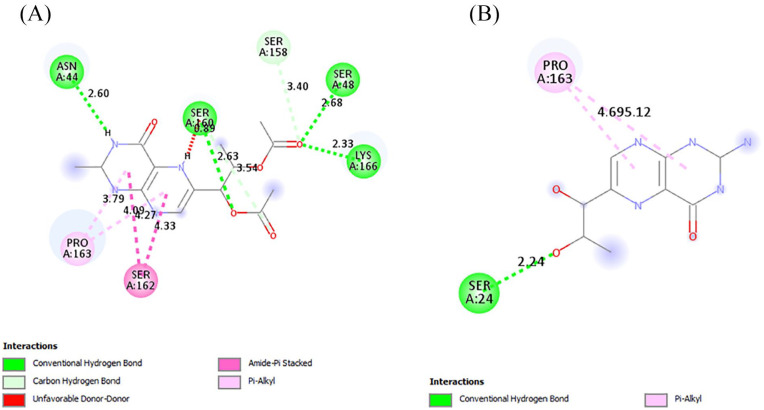

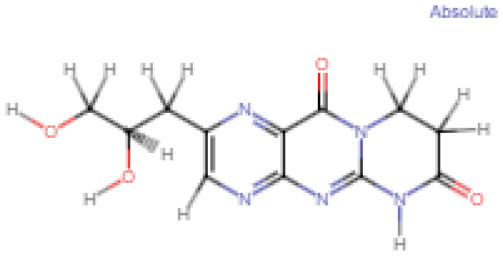

The interactions of the ligands in the active site of PfPTPS were analyzed with Discovery Studio 2021 client. The interactions shown from the post-screening analyses include hydrogen bonds, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic bonds (Table 4). The binding affinity is the strength of and is influenced by these interactions. 34 Compound 140296439 in its different poses made up 3 of the 7 best hits, taking up positions 1 to 3. These different poses shown in Figure 3 contributed to the different types of interactions as well as residues to which it was bonded. This compound possesses 6 hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and 1 hydrogen bond donor (HBD). This compound and its interactions in the 3 poses are shown in Figures 4 and 5A. However, the high-binding energies suggest the strong affinity of this compound to the enzyme. This compound should be further studied for its affinity and possible inhibitory actions on PfPTPS. The first pose (Figure 3A) with a docking score of −7.2 kcal/mol forms 3 hydrogen bonds with SER160, ASN46 and GLU19, 2 electrostatic bonds with LYS166 and GLU19, and a hydrophobic bond with LYS166. The second pose of compound 140296439 (Figure 3B) with a binding energy of −7.1 kcal/mol formed 2 hydrogen bonds with SER24 and ASN44 and a hydrophobic bond with PRO163. The third pose (Figure 3C) with a binding energy of −7.0 kcal/mol forms hydrogen bonds with ASN46 and GLU156, electrostatic interactions with LYS166 and GLU19, and hydrophobic interactions with LYS166. With a binding energy of −6.8 kcal/mol, 5HBA and 3HBD compound 140296495 formed 6 hydrogen bonds with the active sites of the enzyme. It formed 2 hydrogen bonds with SER88 and single bonds with ILE86, LEU91, LYS92, and PHE93, and hydrophobic interactions with PHE93 and ILE100 are shown in Figure 5B. Compound 144380406 possesses 7HBA and 3HBD and formed 2 hydrogen bonds with SER160 and LYS166 (Figure 6A). Compound 135573878 bonded to the active sites of the enzyme with a binding energy of −6.7 kcal/mol. With 7HBA and 3HBD, it formed hydrogen bonds with ASN44, SER160, and LYS166 and hydrophobic interactions with PRO163. Compound 136075207 with 8HBA and 1HBD formed hydrogen bonds with ASN44, SER48, SER160, LYS166, SER158, and SER160. The control compound biopterin (135449517) with 6HBA and 4HBD bonded to the enzyme at a binding energy of −5.7 kcal/mol which is significantly lower than the top hits selected (Figure 7). It formed hydrogen bonds with SER24 and hydrophobic interactions with PRO163. With the exception of the control compound, 140296495 did not form any unfavorable bonds with the active site of PfPTPS (Figure 5B).

Table 4.

The type of interactions and the bond lengths between the ligands and the active site of PfPTPS.

| Serial number | PubChem CID | Hydrogen bond acceptors | Hydrogen bond donors | Bond lengths and interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 140296439 (First Pose) | 6 | 1 | Hydrogen bonds: Conventional Hydrogen Bond: SER160 (2.70 Å), ASN 46 (3.02 Å) Carbon-Hydrogen Bond: GLU 19 (3.30 Å) Electrostatic interactions: Pi-Cation: LYS166 (3.05 Å) Attractive Charge: GLU 19 (4.16 Å) Hydrophobic interactions: Pi-Alkyl: LYS166 (5.13 Å) |

| 2 | 140296439 (Second Pose) | 6 | 1 | Hydrogen bonds: Conventional Hydrogen Bond: SER 24 (2.84 Å) Carbon-Hydrogen Bond: ASN 44 (3.66 Å) Hydrophobic interactions: Pi-Alkyl: PRO 163 (4.80 Å) |

| 3 | 140296439 (Third Pose) | 6 | 1 | Hydrogen bonds: Carbon-Hydrogen Bond: ASN 46 (3.58 Å), GLU 156 (3.64 Å) Electrostatic interactions: Pi-Anion/Pi-Cation/Attractive Charge: LYS 166 (2.56 Å, 3.20 Å), GLU 19 (4.09 Å, 3.48 Å) Hydrophobic interactions: Pi-Alkyl: LYS 166 (5.27 Å) |

| 4 | 140296495 | 5 | 3 | Hydrogen bonds: Conventional Hydrogen Bond: ILE 86 (2.89 Å), SER 88 (2.82 Å, 2.52 Å), LEU91 (2.83 Å), PHE93 (2.04 Å), LYS92 (3.17 Å) Hydrophobic interactions: Alkyl/Pi-Alkyl: ILE 100 (4.89 Å), PHE93 (5.25 Å) Pi-Pi T-Shaped: PHE93 (5.32 Å, 5.41 Å) |

| 5 | 144380406 | 7 | 3 | Hydrogen bonds: Conventional Hydrogen Bond: SER160 (2.09 Å), LYS166 (2.27 Å) |

| 6 | 135573878 | 7 | 2 | Hydrogen bonds: Conventional Hydrogen Bond: ASN44 (2.92 Å), SER160 (3.01 Å), LYS166 (2.28 Å) Hydrophobic interactions: Pi-Alkyl: PRO163 (4.99 Å, 4.60 Å) |

| 7 | 136075207 | 8 | 1 | Hydrogen bonds: Conventional Hydrogen Bond: ASN44 (2.60 Å), SER160 (2.63 Å), SER48 (2.68 Å), LYS166 (2.33 Å) Carbon-Hydrogen Bond: SER158 (3.40 Å), SER160 (3.54 Å) Hydrophobic interactions: Pi-Alkyl: PRO163 (3.79 Å, 4.09 Å) Amide-Pi Stacked: SER162 (4.27 Å, 4.33 Å) |

| 8 | 135449517 (biopterin) | 6 | 4 | Hydrogen bonds: Conventional Hydrogen Bond: SER24 (2.24 Å) Hydrophobic interactions: Pi-Alkyl: PRO163 (4.69 Å, 5.12 Å) |

Abbreviation: PfPTPS, Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.

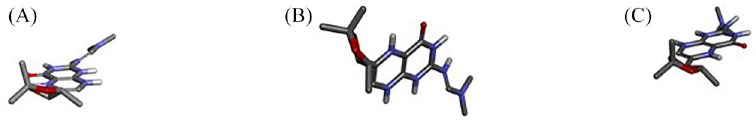

Figure 3.

The different poses of compound 140296439; (A)Pose 1, (B)Pose 2, (C) Pose 3.

Figure 4.

The interactions of the first (A) and second (B) pose of compound 140296439 with the active site of PfPTPS. PfPTPS indicates Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.

Figure 5.

The intermolecular interactions between the active site of PfPTPS and the third pose of compound 140296439 (A) and compound 140296495 (B). PfPTPS indicates Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.

Figure 6.

The intermolecular interactions between the active site of PfPTPS and compound 144380406 (A) and compound 135573878 (B). PfPTPS indicates Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.

Figure 7.

The intermolecular interactions between the active site of PfPTPS and compound 136075207 (A) and the control compound biopterin, 135449517 (B). PfPTPS indicates Plasmodium falciparum 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase.

The drug-like and absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties of the best hits

The drug-like and ADMET properties of the hits are shown in Table 4. Compounds with lesser molecular weight are more easily distributed, therefore the standard of 500 g/mol. The molecular weights of these compounds were within the range of 291.00 and 332.00 g/mol which is below the set standard. The cLogP is an indicator of hydrophilicity and absorption, values greater than 5 are considered highly hydrophilic with poor absorption. The study predicted for all compounds cLogP values less than 5. The TPSA is an indicator of oral bioavailability and according to the Veber rule must not be greater than 140; all hits adhered to this rule and had TPSA less than 140. The log S value is the logarithm of the molar solubility of a compound in water, measured in mol/dm 3 and must be within the ranges of −4 to 6, of which all hits adhered. The drug-likeness of a compound indicates the presence of common drug fragments in the compound. Only compounds 135573878 and 140296495 had negative drug-likeness values of −5.19 and −2.88, respectively. The drug score parameter combines all other predictions into a grand total, a number indicating the drug potential of a compound. A high drug score value, a better chance of a compound’s potential of becoming a drug. The highest drug score value of 0.77 was recorded for compound 136075207. The resulting toxicity properties are color-coded. Properties coded in green implied safety, orange implied mild toxicity, and red implied the chances of unwanted consequences. No compounds showed risk of mutagenicity, tumorigenicity, or reproductive toxicity. Compounds 140296439 and 144380406 were predicted to have high irritant risk.

Discussion

The best hits’ binding affinities were lower than the biopterin indicating a high-affinity binding. The type of interactions and their bond lengths between the different compounds and the protein was identified via the post-screening analysis. Compound 140296439 with the lowest binding energy of −7.2 kcal/mol engaged with the protein’s active site by forming 2 conventional hydrogen bonds (SER 160, ASN 46) and 1 carbon-hydrogen bond (GLU 19). This compound in its other poses also made up the next 2 best ligand efficiency with docking scores other 2 poses had low-binding energies of −7.1 and −7 kcal/mol. The binding energies of the compounds are in the order: 140296439 > 140296439 > 140296439 > 140296495 > 144380406 > 135573878 > 136075207 (Table 4). With the exception of 140296495, all the compounds formed interactions with the amino acid residues in the active site as predicted by CASTp (Tables 2 and 5). The ADMET and toxicity study conducted revealed that despite all the compounds possessing good pharmacokinetic properties, some of them still possessed high irritant toxicity risk (Table 4). The drug scores are in the order: 136075207 > 140296439 > 140296495 = 144380406 = 135573878. The toxicity risk can, however, be removed by hit-to-lead optimization, this is because toxicity is caused by the presence of a high-risk fragment/pharmacophore in the compound. 35 This study is, however, limited by the fact that little is known about the PfPTPS enzyme and that known inhibitors have not yet been identified for this enzyme, especially in Plasmodium parasites.

Table 5.

The toxicity risks and ADMET properties of the hits.

|

Abbreviations: ADMET, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity; cLogP, octanol-water partition coefficient; TPSA, topological polar surface area.

Conclusions

The folate biosynthetic pathway is an essential drug target due to its absence in the human host and should not be ignored in the fight against malaria. It still presents opportunities to identify new targets and design inhibitors and drugs against these targets. In this study, following ligand library preparation and processing, we employed the molecular docking process to identify hit compounds with lower binding energies than the ligand, biopterin. We recommend that stability studies and confirmatory in vitro and in vivo studies be undertaken, as well as employing hit-to-lead (H2L) optimization necessary to remove the observed toxicity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Oluwadunni Elebiju for assisting with the virtual screening.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Covenant Applied Informatics and Communication Africa Center of Excellence (CApIC-ACE) under the World Bank Africa Center of Excellence (ACE Impact) project.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: SNC, MBO and EA: Conceptualization; MBO and EO: Paper writing; MBO, EO and RA : Data collection and analysis; SNC and EA: Critical revision and supervision.

Research Ethics and Patient Consent: Not applicable.

References

- 1. Kwiatkowski DP. How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach us about malaria. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:171-192. doi: 10.1086/432519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williams TN, Mwangi TW, Roberts DJ, et al. An immune basis for malaria protection by the sickle cell trait. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e128-0445. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.0020128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO. World malaria report 2022; 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arrow KJ, Panosian C, Gelband H. Antimalarial drugs and drug resistance. In: Saving Lives, Buying Time: Economics of Malaria Drugs in an Age of Resistance. National Academies Press; 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215631/. Accessed May 9, 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tse EG, Korsik M, Todd MH. The past, present and future of anti-malarial medicines. Malar J. 2019;18:1-21. doi: 10.1186/S12936-019-2724-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Estrada A, Wright DL, Anderson AC. Antibacterial antifolates: from development through resistance to the next generation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6. doi: 10.1101/CSHPERSPECT.A028324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Visentin M, Zhao R, Goldman ID. The antifolates. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26:629. doi: 10.1016/J.HOC.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, et al. Polymorphisms in plasmodium falciparum DHFR and DHPS genes and age related in vivo sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance in malaria-infected patients from Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2005;95:183-193. doi: 10.1016/J.ACTATROPICA.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alker AP, Kazadi WM, Kutelemeni AK, Bloland PB, Tshefu AK, Meshnick SR. DHFR and DHPS genotype and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine treatment failure in children with falciparum malaria in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:1384. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-3156.2008.02150.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gregson A, Plowe CV. Mechanisms of resistance of malaria parasites to antifolates. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:117-145. doi: 10.1124/PR.57.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ploom T, Thöny B, Yim J, et al. Crystallographic and kinetic investigations on the mechanism of 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:851-860. doi: 10.1006/JMBI.1998.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gnaneswaran B, Gladstone M. The febrile illness of malaria: an overview of assessment, management and its prevention. Paediatr Child Health. 2021;31:163-166. doi: 10.1016/J.PAED.2021.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walker IS, Rogerson SJ. Pathogenicity and virulence of malaria: sticky problems and tricky solutions. Virulence. 2023;14. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2022.2150456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pribat A, Jeanguenin L, Lara-Núñez A, et al. 6-Pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase paralogs replace the folate synthesis enzyme dihydroneopterin aldolase in diverse bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4158-4165. doi:10.1128/JB.00416-09/SUPPL_FILE/TABLE_S2.ZIP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hyde JE, Dittrich S, Wang P, Sims PF, de Crécy-Lagard V, Hanson AD. Plasmodium falciparum: a paradigm for alternative folate biosynthesis in diverse microorganisms. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:502-508. doi: 10.1016/J.PT.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baptista V, Costa MS, Calçada C, et al. The future in sensing technologies for malaria surveillance: a review of hemozoin-based diagnosis. ACS Sens. 2021;6:3898-3911. doi: 10.1021/ACSSENSORS.1C01750/ASSET/IMAGES/MEDIUM/SE1C01750_0005.GIF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dittrich S, Mitchell SL, Blagborough AM, et al. An atypical orthologue of 6-pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase can provide the missing link in the folate biosynthesis pathway of malaria parasites. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:609-618. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-2958.2007.06073.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Metz J. Folic acid metabolism and malaria. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28(4 Suppl.):S540-S549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khairallah A, Tastan Bishop Ö, Moses V. AMBER force field parameters for the Zn (II) ions of the tunneling-fold enzymes GTP cyclohydrolase I and 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase. J Biomol Struct Dynam. 2020;39:5843-5860. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1796800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vardhan S, Sahoo SK. In silico ADMET and molecular docking study on searching potential inhibitors from limonoids and triterpenoids for COVID-19. Comput Biol Med. 2020;124:103936. doi: 10.1016/J.COMPBIOMED.2020.103936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katsila T, Spyroulias GA, Patrinos GP, Matsoukas MT. Computational approaches in target identification and drug discovery. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2016;14:177-184. doi: 10.1016/J.CSBJ.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bateman A, Martin MJ, Orchard S, et al. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D523-D531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, et al. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In: Walker JM, ed. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. 1st ed. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 2005:571-607. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Geourjon C, Deléage G. SOPMA: significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus prediction from multiple alignments. Comput Appl Biosci. 1995;11:681-684. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/11.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tian W, Chen C, Lei X, Zhao J, Liang J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W363-W367. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKY473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D1373-D1380. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKAC956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O’Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dallakyan S, Olson AJ. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1263:243-250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, et al. UCSF Chimera? A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605-1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yousafi Q, Ali HA, Rashid H, Khan MS. In silico comparative proteomic analysis of enzymes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis in castor bean (Ricinus communis) and soybean (Glycine max). Turk J Botany. 2019;43:1-26. doi: 10.3906/bot-1708-48. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Panda S, Chandra G. Physicochemical characterization and functional analysis of some snake venom toxin proteins and related non-toxin proteins of other chordates. Bioinformation. 2012;8:891-896. doi: 10.6026/97320630008891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Enany S. Structural and functional analysis of hypothetical and conserved proteins of Clostridium tetani. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7:296-307. doi: 10.1016/J.JIPH.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saranya R, Jayapriya J, Tamil Selvi A. Purification, characterization, molecular modeling and docking study of fish waste protease. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;118:569-583. doi: 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2018.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kastritis PL, Bonvin AM. On the binding affinity of macromolecular interactions: daring to ask why proteins interact. J R Soc Interface. 2013;10. doi: 10.1098/RSIF.2012.0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oduselu GO, Afolabi R, Ademuwagun I, Vaughan A, Adebiyi E. Structure-based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, and molecular dynamics simulation studies for identification of Plasmodium falciparum 5-aminolevulinate synthase inhibitors. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;9:3969. doi: 10.3389/FMED.2022.1022429/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]