Abstract

The lipooligosaccharide (LOS) present in the outer membrane of Haemophilus ducreyi is likely a virulence factor for this sexually transmitted pathogen. An open reading frame in H. ducreyi 35000 was found to encode a predicted protein that had 87% identity with the protein product of the gmhA (isn) gene of Haemophilus influenzae. In H. influenzae type b, inactivation of the gmhA gene caused the synthesis of a significantly truncated LOS which possessed only lipid A and a single 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulosonic acid molecule (A. Preston, D. J. Maskell, A. Johnson, and E. R. Moxon, J. Bacteriol. 178:396–402, 1996). The H. ducreyi gmhA gene was able to complement a gmhA-deficient Escherichia coli strain, a result which confirmed the identity of this gene. When the gmhA gene of H. ducreyi was inactivated by insertion of a cat cartridge, the resultant H. ducreyi gmhA mutant, 35000.252, expressed a LOS that migrated much faster than wild-type LOS in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. When the wild-type H. ducreyi strain and its isogenic gmhA mutant were used in the temperature-dependent rabbit model for dermal lesion production by H. ducreyi, the gmhA mutant was found to be substantially less virulent than the wild-type parent strain. The H. ducreyi gmhA gene was amplified by PCR from the H. ducreyi chromosome and cloned into the pLS88 vector. When the H. ducreyi gmhA gene was present in trans in gmhA mutant 35000.252, expression of the gmhA gene product restored the virulence of this mutant to wild-type levels. These results indicate that the gmhA gene product of H. ducreyi is essential for the expression of wild-type LOS by this pathogen.

Haemophilus ducreyi, a gram-negative coccobacillus, is the etiologic agent of the sexually transmitted disease known as chancroid. This ulcerogenital disease is endemic in areas of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (63), and a resurgence of chancroid has been seen in the United States since early in the 1980s (63). With the finding that chancroid as well as other genital ulcer diseases are significant risk factors for the transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (63), there has been renewed research effort to elucidate the pathogenic mechanisms and virulence factors of H. ducreyi.

To date, several putative virulence factors of this organism have been identified; these include a cell-associated hemolysin with cytotoxic activity (2, 43), a soluble cytotoxin (12, 50), a hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein (18, 61), a novel pilus (6), and a copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (52). In addition, gene products which may directly or indirectly regulate the expression of H. ducreyi virulence factors have been identified (11, 44).

As might be expected, the lipooligosaccharide (LOS) of the H. ducreyi outer membrane has been shown to have potent inflammatory ability (10). Physicochemical analyses of H. ducreyi LOS indicate that it is very similar to the LOS of other gram-negative mucosal surface pathogens, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Haemophilus influenzae (22, 36–38, 56). Lactosamine and sialyllactosamine have been identified as the terminal saccharides of the H. ducreyi LOS oligosaccharide chain (37, 38, 56), and a gene encoding cytidine-5′-monophosphate N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase, an enzyme involved in the ability of this organism to sialylate its LOS (37), has been cloned from H. ducreyi (66).

Only recently have attempts been made to address the possible involvement of the oligosaccharide portion of H. ducreyi LOS in the pathogenesis of chancroid. Mutants defective in the expression of LOS have been described (9, 21, 60), and while at least four different genes whose encoded protein products are directly or indirectly involved in H. ducreyi LOS expression have been cloned and sequenced (21, 60, 66), only one of these has been tested by mutant analysis in relevant in vitro and in vivo systems. An H. ducreyi mutant defective in the expression of an RfaK homolog was shown to exhibit a reduced ability to attach to and invade human keratinocytes in vitro (21). Virulence testing of an independently constructed H. ducreyi rfaK (i.e., lbgB) mutant in the temperature-dependent rabbit model for experimental chancroid (49) yielded equivocal results (60).

In the present study, a gene (gmhA) encoding a phosphoheptose isomerase essential for the expression of wild-type LOS by H. ducreyi 35000 was identified and shown to complement an Escherichia coli gmhA mutant. Inactivation of the H. ducreyi gmhA gene resulted in the expression of a truncated LOS molecule. In addition, the isogenic gmhA mutant exhibited significantly reduced virulence in an animal model for experimental chancroid. Provision of the wild-type H. ducreyi gmhA gene in trans in the isogenic mutant restored both wild-type LOS expression and virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Some of the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (51). LB medium was supplemented, when appropriate, with ampicillin, chloramphenicol, or kanamycin at a final concentration of 100, 30, or 30 μg/ml, respectively. H. ducreyi strains were grown on chocolate agar (CA) plates containing 1% (vol/vol) IsoVitaleX (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) as previously described (49). H. ducreyi strains were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air–5% CO2 at 33°C. CA plates supplemented with chloramphenicol at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml were used for mutant selection. For complementation studies involving H. ducreyi, kanamycin was included in CA at a final concentration of 30 μg/ml. In growth studies, H. ducreyi strains were grown at 33°C with slow shaking in a water bath; growth was monitored by measurement of culture turbidity. A modified Haemophilus somnus liquid medium (29) was used in these growth studies and consisted of filter-sterilized Columbia broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) Tris base, 1% (vol/vol) IsoVitaleX, and heme at a final concentration of 25 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Host strain for cloning experiments | 51 |

| HB101 | Host strain essential for propagating plasmids carrying mutated H. ducreyi DNA inserts for use in electroporation | 51 |

| χ705 | F−leu-4 φr Strrarg-35 T6r λ− | 14 |

| χ711 | Deletion mutant of χ705 lacking the gmhA and proAB genes; expresses a truncated LPS molecule which migrates very rapidly in SDS-PAGE relative to that of χ705 | 7, 14 |

| H. ducreyi | ||

| 35000 | Wild-type strain isolated in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada; expresses a LOS that binds MAb 3E6 | 23 |

| 35000.7 | Isogenic LOS mutant with a cat cartridge inserted into the rfaK (lbgB) gene; expresses a truncated LOS molecule that does not bind MAb 3E6 | 60 |

| 35000.252 | Isogenic LOS mutant with a cat cartridge inserted into the Ppu10I site within the gmhA gene; expresses a truncated LOS molecule that does not bind MAb 3E6 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pWKS30 | Low-copy-number cloning vector; Ampr | 67 |

| pHD250 | pWKS30 with an 18-kb H. ducreyi 35000 DNA insert containing the gmhA gene | This study |

| pBluescript II KS+ (pBS) | Cloning vector; Ampr | Stratagene |

| pHD251 | pBS with a 1.6-kb PCR-derived insert containing the H. ducreyi 35000 gmhA gene | This study |

| pHD252 | pHD251 with a cat cartridge inserted into the Ppu10I site within the gmhA gene | This study |

| pCR2.1 | Cloning vector; Ampr | Invitrogen |

| pCR253 | pCR2.1 with a 1-kb PCR-derived insert containing the H. ducreyi gmhA gene | This study |

| pLS88 | Cloning vector capable of replication in H. ducreyi; Kanr Smr Sulr | 16 |

| pLS253 | pLS88 with a 1-kb PCR-derived insert containing the H. ducreyi gmhA gene | This study |

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Standard techniques, such as restriction enzyme digestions, ligation, transformation, electroporation of E. coli strains, and plasmid purification, have been described elsewhere (4, 51). PCR was done with Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, Wis.), 100 ng of each primer (see below), 2.5 mM MgCl2, and deoxynucleoside triphosphates at 200 μM each. Twenty-nine cycles at an annealing temperature of 55°C were performed for each PCR (62). Boiled bacterial cell preparations (27) or chromosomal DNA purified from H. ducreyi was used as the template for PCR.

Chromosomal DNA preparation.

Chromosomal DNA was purified from an overnight culture of H. ducreyi by use of a modification of a method previously described (5). The bacteria were scraped from a single CA plate into 3 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution, and the mixture was centrifuged to pellet the bacteria. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl containing 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and 150 μl of 10% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was added. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min and then at 37°C for 1 h. Next, 200 μl of RNase (10 mg/ml) was added, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and then 20 μl of 5 M NaCl and 20 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml) were added. The mixture was incubated at 56°C for 2 h. One phenol extraction, two phenol-chloroform extractions, and one chloroform extraction were performed in succession as described previously (5). Then, 80 μl of 5 M NaCl and 2 volumes of 100% ethanol were added to the mixture. Precipitated strands of DNA were spooled out on sterile glass rods, rinsed with 70% ethanol, and dissolved in 1 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl–1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0).

Construction of an H. ducreyi genomic library in pWKS30.

Chromosomal DNA purified from H. ducreyi 35000 was partially digested with Sau3AI. Fragments larger than 6 kb were purified by sucrose density gradient centrifugation, ligated into the BamHI site of pWKS30 (67), and used to transform E. coli DH5α.

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

Nucleotide sequence analysis was performed with a model 373 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Both strands of the 1.6-kb H. ducreyi DNA insert in pHD251 were sequenced in their entirety, as were both strands of the same 1.6-kb region in pHD250. DNA sequence information was analyzed through the National Center for Biotechnology Information by use of the BLAST network service to search GenBank (3) and with MacVector sequence analysis software (version 6; Oxford Molecular Group, Campbell, Calif.).

Construction of an isogenic H. ducreyi gmhA mutant.

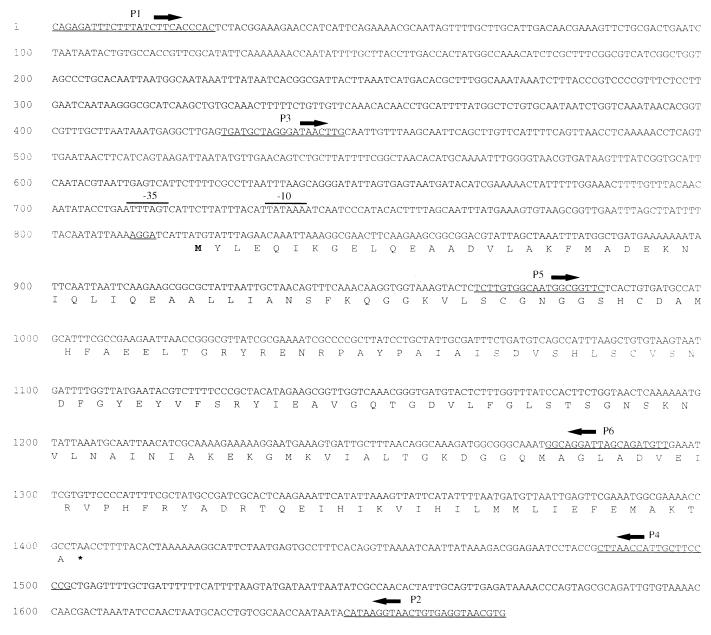

The oligonucleotide primers P1 (5′-GCGGATCCCAGAGATTTCTTTATCTTCACCCAC-3′) and P2 (5′-CGGGATCCCACGTTACCTCACAGTTACCTTATG-3′) (see Fig. 2) were constructed with a BamHI site (underlined) based on information obtained from the nucleotide sequence of the H. ducreyi DNA insert in pHD250. The use of P1 and P2 in PCR together with 400 ng of purified H. ducreyi 35000 chromosomal DNA yielded a 1.6-kb product containing the H. ducreyi gmhA open reading frame (ORF) and flanking DNA. This PCR product was digested with BamHI and then ligated into the BamHI site of pBluescript II KS+. The resultant plasmid (pHD251) was digested with Ppu10I, which cut within the ORF of the gmhA gene. Ppu10I-digested pHD251 was treated with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) to create blunt ends and then with shrimp alkaline phosphatase (United States Biochemical Corp.). A 1.4-kb cartridge carrying the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene (cat) (24) was then blunt-end ligated into pHD251 to obtain pHD252. The latter plasmid was used to transform E. coli HB101. Plasmid pHD252 was purified by cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation and linearized by digestion with BsaI. The linearized form of pHD252 was used to electroporate H. ducreyi 35000 (24), and transformants were selected on CA plates supplemented with chloramphenicol.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of the H. ducreyi 35000 gmhA gene and its predicted protein product; the sequence is from the DNA insert in pHD251 (Fig. 1). Lines above the sequence show putative −10 and −35 regions. A putative Shine-Dalgarno site is underlined. Oligonucleotide primers used in PCR are underlined and labeled P1 to P6 with directional arrows.

E. coli HB101 was used for propagating pHD252 prior to the use of this DNA for electroporation of H. ducreyi. For reasons that remain to be determined, mutated H. ducreyi DNA inserts from plasmids propagated in some other E. coli strains, including DH5α, do not allow successful electroporation of H. ducreyi (data not shown).

Complementation of E. coli χ711 with the H. ducreyi gmhA gene.

A 1-kb PCR product containing the H. ducreyi gmhA gene was prepared by use of 400 ng of H. ducreyi 35000 chromosomal DNA template together with the oligonucleotide primers P3 (5′-CGGAATTCTGATGCTAGGGATAACTTG-3′) and P4 (5′-CCGAGCTCCGGGGAAGCAATGGTTAAG-3′) (see Fig. 2); the underlined sequences indicate EcoRI and SacI sites, respectively. This 1-kb fragment was ligated into the pCR2.1 vector from a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The ligation reaction mixture was used to transform E. coli DH5α; transformants were selected on LB agar supplemented with ampicillin. A plasmid (pHD253) from one of these transformants was used to electroporate E. coli χ711 (7, 14); selection was accomplished on LB agar containing ampicillin.

Complementation of the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant.

The 1-kb PCR product described immediately above was digested with both EcoRI and SacI and then ligated into pLS88 (16) which had been digested with the same two restriction enzymes. The ligation reaction mixture was used to transform E. coli DH5α; transformants were selected on LB agar containing kanamycin. Plasmid pLS253, obtained from one of these transformants, was purified by a miniprep procedure and used to electroporate H. ducreyi gmhA mutant 35000.252. The complemented H. ducreyi mutants were selected on CA containing both kanamycin and chloramphenicol.

MAb and colony blot radioimmunoassay.

Monoclonal antibody (MAb) 3E6 is specific for a surface-exposed epitope in H. ducreyi 35000 LOS and has been described elsewhere (60). The colony blot radioimmunoassay was performed as described previously (60) with MAb 3E6 culture supernatant as the source of the primary antibody.

Southern blot analysis.

Purified H. ducreyi 35000 chromosomal DNA was digested to completion with AflIII or HindIII, subjected to electrophoresis in a 0.7% (wt/vol) agarose gel, transferred to nitrocellulose paper, and probed by Southern blot analysis as previously described (51). A DNA probe comprising 330 bp internal to the H. ducreyi gmhA gene was constructed by PCR with the oligonucleotide primers P5 (5′-TCTTGTGGCAATGGCGGTTC-3′) and P6 (5′-AACATCTGCTAATCCTGCC-3′) (see Fig. 2). The 1.4-kb cat cartridge was also used as a probe for Southern blot analysis. These two DNA probes were radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP by use of a random-primer DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) and purified on Quick Spin columns (Boehringer).

Analysis of H. ducreyi LOS and E. coli LPS.

Whole-cell lysate preparations of E. coli and H. ducreyi strains were treated with proteinase K as previously described (45), and the LOS or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in these preparations was resolved by Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (35). The resultant gels were either stained with silver (64) or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blot analysis. In the latter instance, nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with PBS containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBS-Tween) and incubated overnight at 4°C with MAb 3E6 culture supernatant. Filters were rinsed three times in PBS-Tween and incubated at room temperature for 2 h with a 1:2,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G in PBS-Tween containing 0.1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin. Filters were rinsed three times with PBS-Tween and then with PBS and developed with PBS containing 4-chloro-1-naphthol and hydrogen peroxide as previously described (30).

Analysis of outer membrane proteins.

The Sarkosyl-insoluble fraction from H. ducreyi cell envelopes was prepared as described previously (33). Proteins present in this fraction were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue.

Virulence testing.

The temperature-dependent rabbit model for experimental chancroid was used to determine the relative virulence of the H. ducreyi strains used in this study (49). These studies involving rabbits were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee. Briefly, eight New Zealand White adult male rabbits were used in each experiment. These animals were housed at a room temperature of 15 to 17°C. All other housing procedures and animal care procedures were performed in accordance with the standards of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Serial dilutions of the H. ducreyi strains were injected intradermally into each animal. Each animal was injected with at most three strains per experiment, with one injection of each dilution of the inoculum. Inocula were encoded prior to injection to prevent bias in the scoring of the resultant lesions. Lesion characteristics were scored as described previously (49) with the following numeric values: 0, no change; 1, erythema; 2, induration; 3, nodule; and 4, pustule or necrosis. Lesion scores were recorded on days 2, 4, and 7 postinfection. On day 7 postinfection, material excised from lesions caused by injection of 105 CFU of H. ducreyi was cultured on CA plates. Recovered organisms were subcultured onto CA supplemented with appropriate antimicrobial compounds to confirm the presence of the relevant antimicrobial resistance markers and were also tested by a colony blot radioimmunoassay with MAb 3E6 to confirm the LOS phenotype. Statistical analyses were performed as described previously (60, 61).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the H. ducreyi gmhA gene was deposited at GenBank and assigned accession number AF045156.

RESULTS

Identification and nucleotide sequence analysis of the gmhA gene of H. ducreyi 35000.

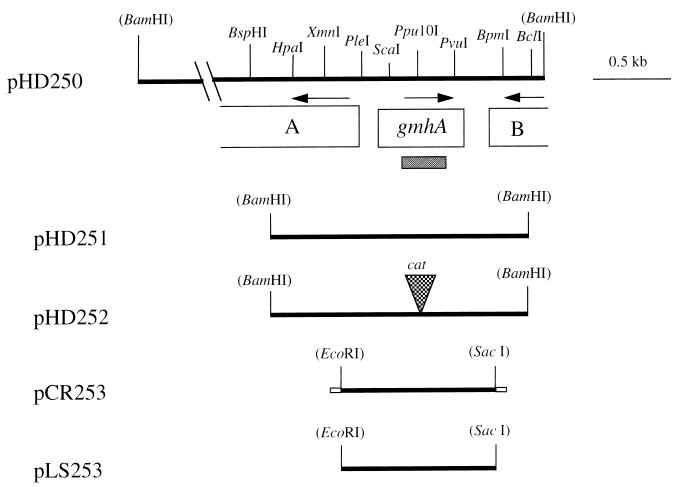

A recombinant clone [E. coli DH5α(pHD250)] derived from an H. ducreyi 35000 genomic library constructed in plasmid vector pWKS30 was observed to give rise to translucent and opaque colonies (data not shown). Nucleotide sequence analysis of 1.6 kb of DNA at one end of the 18-kb H. ducreyi DNA insert in pHD250 detected an ORF (Fig. 1) which encoded a predicted protein with homology to the gmhA gene product of H. influenzae (8). Expression of this H. influenzae gene, also designated isn (47), is essential for both the synthesis of wild-type LOS by H. influenzae type b and the expression of full virulence by this encapsulated pathogen (69). This 1.6-kb region of the DNA insert in pHD250 was found to contain two incomplete predicted ORFs and one complete predicted ORF (Fig. 1). The complete ORF, encoding the GmhA-like protein, was transcribed in the opposite direction from the other two ORFs (Fig. 1). Of the two incomplete ORFs, one (ORF A) encoded a protein with homology to a transcriptional regulatory protein (HI0410) of H. influenzae (20), and the other (ORF B) most closely resembled a hypothetical ORF (HI1586) of H. influenzae (20). These two ORFs were not analyzed further.

FIG. 1.

Partial restriction map of the H. ducreyi 35000 chromosomal DNA insert in pHD250 and related plasmids. A and B indicate incomplete ORFs upstream and downstream of gmhA, respectively. Restriction sites in parentheses indicate vector cloning sites. Arrows indicate the predicted direction of transcription. The cross-hatched bar beneath the gmhA gene indicates the 330-bp probe used for the Southern blot analysis shown in Fig. 4. Plasmid pHD251 contains a 1.6-kb PCR product. A cat cartridge was ligated into the Ppu10I site of pHD251 to construct pHD252. Plasmid pCR253 is pCR2.1 with a 1-kb PCR product containing the gmhA gene and flanking DNA; the small boxes on the ends of this insert represent nucleotides involved in cloning into the pCR2.1 vector. Plasmid pLS253 is pLS88 with the aforementioned 1-kb PCR product cloned into the EcoRI and SacI sites of this vector.

The H. ducreyi gmhA ORF was 585 nucleotides long (nucleotides 822 to 1406 in Fig. 2) and encoded a predicted protein with a calculated molecular mass of 21,302 Da (Fig. 2). BLAST searches of nonredundant DNA and protein databases revealed that the deduced amino acid sequence of the H. ducreyi GmhA protein was 87% identical and 93% similar to that of the GmhA protein of H. influenzae (8, 47) and 73% identical and 84% similar to that of the GmhA protein of E. coli (7).

Complementation of an E. coli gmhA mutant with the H. ducreyi gmhA gene homolog.

The high degree of identity between the GmhA protein of E. coli and the predicted protein encoded by the H. ducreyi gmhA gene homolog led us to determine whether this similarity was reflected at the functional level. To accomplish this, the entire gmhA gene of H. ducreyi 35000 was amplified by PCR and inserted into cloning vector pCR2.1, yielding recombinant plasmid pCR253. This plasmid was used to electroporate E. coli χ711, which has been shown to contain a chromosomal deletion of the gmhA gene (7). One of the resultant transformants [χ711(pCR253)] was selected for further study.

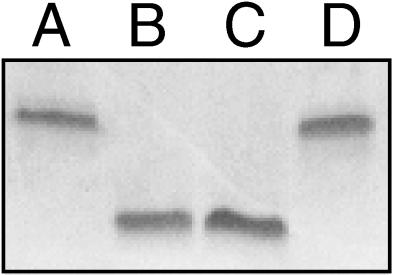

The LPS molecules present in proteinase K-treated whole-cell lysates of the relevant E. coli strains were analyzed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3). As expected from a recent study (7), the truncated LPS of strain χ711 (Fig. 3, lane B) migrated much more rapidly in SDS-PAGE than did the LPS of strain χ705 (Fig. 3, lane A), the immediate parent of strain χ711 (14). The presence of vector pCR2.1 in χ711 did not affect the rate of migration of the LPS (Fig. 3, lane C). In contrast, the LPS of χ711(pCR253) (Fig. 3, lane D) migrated much more slowly, at a rate that was indistinguishable from that of the LPS of the χ705 parent strain. This latter result indicated that the H. ducreyi gmhA gene was able to complement an E. coli gmhA mutant.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis of LPSs expressed by gmhA-deficient E. coli χ711 and related E. coli strains. LPS present in proteinase K-treated whole-cell lysates was resolved by Tricine-SDS-PAGE and stained with silver. Lanes: A, E. coli χ705 with a wild-type E. coli gmhA gene; B, E. coli χ711; C, E. coli χ711 containing the pCR2.1 vector; D, E. coli χ711 containing pCR253 with the wild-type H. ducreyi gmhA gene.

No recombinant E. coli strains containing pCR253 gave rise to the opaque and translucent colony variants originally observed with E. coli DH5α(pHD250). This result indicated that the genetic element(s) responsible for the opaque and translucent colony variation must be located in the remaining 16 kb of H. ducreyi DNA in pHD250. Further analysis of this 16-kb region of H. ducreyi DNA was not performed in this study.

Construction of an isogenic H. ducreyi gmhA mutant.

To confirm that the gmhA gene of H. ducreyi was involved in LOS biosynthesis, an isogenic gmhA mutant was constructed by allelic exchange. A cat cartridge was ligated into the Ppu10I restriction site of the gmhA gene in pHD251 (Fig. 1). The resultant plasmid, pHD252, was linearized by digestion with BsaI and used to electroporate H. ducreyi 35000. Ten chloramphenicol-resistant H. ducreyi transformants were tested initially by PCR (with oligonucleotide primers P1 and P2 [Fig. 2]) to detect the occurrence of allelic exchange involving the replacement of the wild-type gmhA gene with the mutated allele containing the cat cartridge. Nine of these 10 chloramphenicol-resistant transformants yielded two or more PCR products, consistent with a single crossover event. Only one of these transformants, strain 35000.252, yielded a single PCR product with the correct predicted size of 3 kb, representing the disrupted 1.6-kb gmhA gene containing the 1.4-kb cat cartridge.

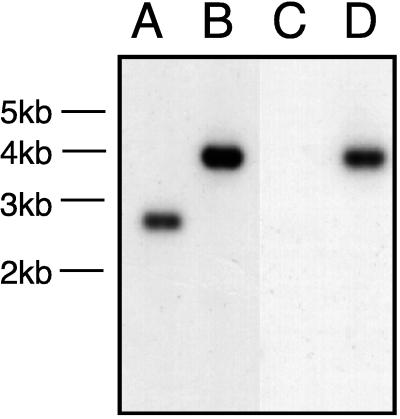

Southern blot analysis was performed to confirm that strain 35000.252 was an isogenic gmhA mutant. When chromosomal DNA from wild-type parent strain 35000 was probed with a 330-bp fragment from the H. ducreyi gmhA gene (Fig. 1), a 2.7-kb AflIII fragment hybridized with this probe (Fig. 4, lane A). This same probe hybridized with a 4-kb AflIII fragment of chromosomal DNA from strain 35000.252 (Fig. 4, lane B). This result is consistent with the replacement of the wild-type gmhA gene with the mutated allele containing the 1.4-kb cat cartridge. When the cat cartridge was used as a probe, a 4-kb AflIII fragment from 35000.252 also hybridized with this cat cartridge (Fig. 4, lane D). Chromosomal DNA from wild-type parent strain 35000 failed to hybridize with the cat cartridge probe (Fig. 4, lane C).

FIG. 4.

Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA preparations from wild-type H. ducreyi 35000 (lanes A and C) and isogenic gmhA mutant 35000.252 (lanes B and D). Chromosomal DNAs were digested with AflIII, resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, and probed with either a 330-bp PCR product derived from the H. ducreyi gmhA gene (lanes A and B) or the cat cartridge (lanes C and D). Size markers are on the left side of the figure.

Characterization of the isogenic gmhA mutant.

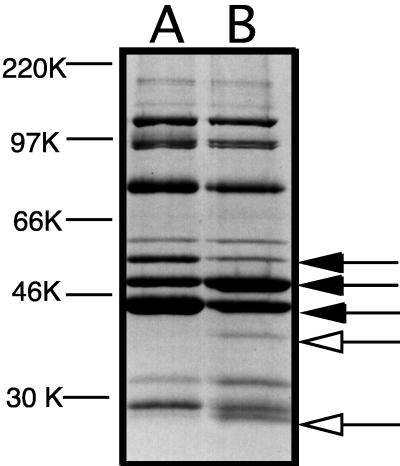

Growth of wild-type strain 35000 and gmhA mutant 35000.252 in broth revealed that both strains grew at the same rates and to the same final densities (data not shown). The outer membrane of the gmhA mutant (Fig. 5, lane B) did not lack any proteins expressed by that of the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 5, lane A), although some major outer membrane proteins of these two strains differed in their relative abundances (Fig. 5, closed arrows). Two minor proteins present in the gmhA mutant (Fig. 5, open arrows) were absent in the wild-type parent strain; one of these may be the 26-kDa protein encoded by the cat gene.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of outer membrane proteins from wild-type and mutant H. ducreyi strains. Proteins present in the Sarkosyl-insoluble cell envelope fraction from wild-type parent strain 35000 (lane A) and isogenic gmhA mutant 35000.252 (lane B) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. The three closed arrows indicate major outer membrane proteins whose relative abundances in these two strains were different. The two open arrows indicate the two proteins which were present in the mutant but absent in the wild-type parent strain. Molecular weight markers (in thousands [K]) are shown on the left side of the figure.

SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining showed that the LOS molecules of strains 35000, 35000.7, and 35000.252 all migrated at different rates. The LOS of wild-type strain 35000 migrated at the lowest rate (Fig. 6, panel 1, lane A). The LOS of isogenic gmhA mutant 35000.252 (Fig. 6, panel 1, lane C) migrated the fastest, whereas the LOS of rfaK (lbgB) mutant 35000.7 (Fig. 6, panel 1, lane B) migrated at an intermediate rate. These results suggested that the oligosaccharide component of the LOS of the gmhA mutant was shorter than that of the rfaK (lbgB) mutant. In Western blot analysis with MAb 3E6, wild-type strain 35000 was used as the positive control and rfaK (lbgB) mutant 35000.7 was used as the negative control (60). MAb 3E6 readily bound the LOS of strain 35000 (Fig. 6, panel 2, lane A) but failed to bind the LOS of both rfaK (lbgB) mutant 35000.7 and gmhA mutant 35000.252 (Fig. 6, panel 2, lanes B and C, respectively).

FIG. 6.

Characterization of the LOSs expressed by wild-type, mutant, and complemented mutant strains of H. ducreyi. LOS present in proteinase K-treated whole-cell lysates was resolved by SDS-PAGE and either stained with silver (panel 1) or transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blot analysis with the H. ducreyi LOS-specific MAb 3E6 (panel 2). Lanes: A, wild-type strain 35000; B, rfaK (lbgB) mutant 35000.7; C, isogenic gmhA mutant 35000.252; D, 35000.252(pLS88); E, 35000.252(pLS253).

Complementation of the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant.

To eliminate the possibility that an undetected secondary mutation was responsible for the altered LOS phenotype of the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant, complementation analysis was performed. The wild-type H. ducreyi gmhA gene was cloned into pLS88, yielding recombinant plasmid pLS253 (Fig. 1). Both the pLS88 vector and pLS253 were used to electroporate H. ducreyi gmhA mutant 35000.252. The presence of the vector alone in the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant [i.e., strain 35000.252(pLS88)] (Fig. 6, panels 1 and 2, lanes D) had no detectable effect on the migration rate or antigenic characteristics of the LOS relative to those of the LOS of strain 35000.252 (Fig. 6, panels 1 and 2, lanes C). In contrast, the presence of the wild-type H. ducreyi gmhA gene in trans in the gmhA mutant [i.e., strain 35000.252(pLS253)] (Fig. 6, panels 1 and 2, lanes E) resulted in the expression of a LOS molecule which had a migration rate and an MAb 3E6 reactivity indistinguishable from those of the wild-type LOS (Fig. 6, panels 1 and 2, lanes A).

Virulence expression by the gmhA mutant.

Isogenic gmhA mutant 35000.252 was tested for the ability to produce dermal lesions in the temperature-dependent rabbit model (49). In two independent experiments, mean lesion scores obtained with wild-type strain 35000 were consistently higher than those obtained with the gmhA mutant for all sampling times and inocula (Table 2, experiments A and B). These apparent differences in lesion scores were highly significant (P ≤ 0.0001). On day 7 postinfection, viable H. ducreyi organisms were recovered only from lesions produced by wild-type strain 35000.

TABLE 2.

Lesion formation by wild-type, gmhA mutant, and complemented gmhA mutant strains of H. ducreyi in the temperature-dependent rabbit modela

| Expt | Strain | Inoculum size (CFU) | Mean ± SD lesion score on day:

|

Pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 7 | ||||

| A | 35000 (wild type) | 105 | 3.38 ± 0.48 | 3.88 ± 0.33 | 4.00 ± 0 | |

| 35000.252 (gmhA mutant) | 105 | 1.63 ± 0.48 | 1.25 ± 0.43 | 1.63 ± 0.70 | 0.0001 | |

| 35000 (wild type) | 104 | 3.00 ± 0 | 3.00 ± 0 | 3.75 ± 0.43 | ||

| 35000.252 (gmhA mutant) | 104 | 1.25 ± 0.66 | 0.63 ± 0.48 | 1.00 ± 0.87 | ||

| B | 35000 | 105 | 3.88 ± 0.33 | 3.88 ± 0.33 | 4.00 ± 0 | |

| 35000.252 | 105 | 2.13 ± 0.60 | 1.63 ± 0.48 | 1.25 ± 0.66 | 0.0001 | |

| 35000 | 104 | 3.13 ± 0.60 | 2.88 ± 0.78 | 3.00 ± 1.11 | ||

| 35000.252 | 104 | 1.50 ± 0.71 | 0.88 ± 0.60 | 0.63 ± 0.48 | ||

| C | 35000 | 105 | 4.00 ± 0 | 4.00 ± 0 | 4.00 ± 0 | |

| 35000.252(pLS88) | 105 | 2.25 ± 0.70 | 2.00 ± 0.76 | 1.75 ± 0.46 | 0.0001 | |

| 35000.252(pLS253) | 105 | 4.00 ± 0 | 4.00 ± 0 | 4.00 ± 0 | 0.2773 | |

| 35000 | 104 | 4.00 ± 0 | 3.88 ± 0.35 | 4.00 ± 0 | ||

| 35000.252(pLS88) | 104 | 1.13 ± 0.64 | 0.50 ± 0.76 | 1.25 ± 0.35 | ||

| 35000.252(pLS253) | 104 | 3.75 ± 0.46 | 3.75 ± 0.46 | 3.63 ± 0.74 | ||

Eight rabbits were used in each experiment.

Calculated for the difference between wild-type and test strain lesion scores from both inoculum sizes and from all 3 days. In addition, complemented gmhA mutant 35000.252(pLS253) was significantly more virulent than the gmhA mutant containing the pLS88 vector alone (P ≤ 0.0001).

A third virulence test was performed to demonstrate that complementation with the wild-type H. ducreyi gmhA gene restored the virulence of the gmhA mutant. The gmhA mutant 35000.252(pLS88) containing the plasmid vector alone showed the same markedly decreased level of virulence as the original gmhA mutant, 35000.252 (Table 2, experiment C), whereas complemented gmhA mutant 35000.252(pLS253), with the wild-type H. ducreyi gmhA gene present in trans, had the same level of virulence as wild-type parent strain 35000 (Table 2, experiment C). No viable H. ducreyi organisms were recovered from the lesions produced by the gmhA mutant containing the vector alone. Viable H. ducreyi organisms were recovered at the same frequencies (i.e., five of eight rabbits) from lesions produced by both wild-type parent strain 35000 and complemented gmhA mutant 35000.252(pLS253). The identity of the H. ducreyi organisms recovered from lesions produced by strain 35000.252(pLS253) was confirmed by colony blot analysis with MAb 3E6, by antimicrobial resistance testing, and by Southern blotting (data not shown). This latter Southern blot analysis was performed to confirm that the wild-type gmhA gene in pLS253 had not been exchanged into the chromosome in place of the mutant allele.

Conservation of the gmhA gene among H. ducreyi strains.

Southern blot analysis of 11 strains of H. ducreyi isolated in seven different countries was performed with a 330-bp fragment from the gmhA gene of H. ducreyi 35000 (Fig. 1) as a probe. Strains 35000, Hd9, Hd12, Hd13, 512, 1145, 1151, 1352, Cha-1, R018, and STD101 (60) all showed hybridization of a 2.7-kb AflIII fragment of chromosomal DNA to the probe, indicating the presence of the gmhA gene in all 11 strains (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

It is well accepted that the LPS or LOS molecules present in the outer membranes of gram-negative pathogens play a critical role in disease caused by these organisms because of the inflammatory ability of these amphipathic molecules (48). Not unexpectedly, there is now ample evidence that the LOS of H. ducreyi is capable of inducing the formation of dermal lesions even in the absence of viable organisms (10, 65). Efforts to determine structure-function relationships of H. ducreyi LOS have been assisted by recent advances in knowledge about the physical structure of this molecule (1, 21, 37, 38, 56). However, still relatively little is known about what other role(s) LOS may play in the pathogenesis of chancroid beyond provoking a significant inflammatory response.

Mutant analysis of the LOSs of other pathogens, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae and H. influenzae, has been instrumental in establishing the relevance of the oligosaccharide component of LOS to the pathogenesis of the diseases caused by these organisms (13, 28, 39, 46, 47, 59). Considerable evidence derived from in vitro experiments has indicated that the oligosaccharide component of the LOS of N. gonorrhoeae contributes to the virulence of this mucosal surface pathogen (54, 55). Similarly, the use of relevant animal models has shown that the oligosaccharide component of H. influenzae type b LOS is essential for virulence expression by this encapsulated pathogen (13, 28, 31, 68, 69). More recently, mutant analysis was used to demonstrate the effect of changes in both the lipid A structure and the phosphorylation state of the LOS oligosaccharide on the virulence of nontypeable H. influenzae in an animal model (15).

The first indication that LOS oligosaccharide structure was important in the ability of H. ducreyi to produce disease was obtained over a decade ago (41, 42) in studies which compared different strains or variants of H. ducreyi for their virulence in a rabbit model. These experiments indicated that changes in the migration characteristics of the LOS in SDS-PAGE, which most likely reflected differences in LOS oligosaccharide composition, could be correlated with virulence differences in animals. Mutant analysis of the involvement of H. ducreyi LOS in virulence expression did not begin until relatively recently, when two different laboratories constructed rfaK (lbgB) mutants of H. ducreyi which expressed an LOS with a truncated oligosaccharide (9, 21, 60). Lack of expression of the rfaK (lbgB) gene product adversely affected the ability of H. ducreyi to both attach to and invade human keratinocytes in vitro (9, 21) but did not have a statistically significant effect on the ability of H. ducreyi to produce skin lesions in the temperature-dependent rabbit model (60).

It is particularly relevant to the present study that the first LOS mutant (originally designated I69) of H. influenzae type b which was shown to exhibit reduced virulence in the infant rat model (69) was subsequently found to express a LOS molecule comprised of only lipid A and a single phosphorylated 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulosonic acid residue (26). This LOS molecule, which lacked an oligosaccharide moiety, migrated much more rapidly in SDS-PAGE than did the LOS molecule of the wild-type parent strain (69). Subsequent studies revealed that the I69 mutant possessed a single-base-pair deletion in a previously unidentified gene, designated isn (47). Very shortly after this discovery, it was found that the H. influenzae isn gene was a homolog of the E. coli gmhA gene (previously designated lpcA), which encodes a phosphoheptose isomerase (7, 8). This enzyme catalyzes the conversion of sedoheptulose-7-phosphate into d-glycero-d-mannoheptose-7-phosphate (7), which is essential for the synthesis of the ADP-l-glycero-d-mannoheptose precursor involved directly in the synthesis of the oligosaccharide (17).

The H. ducreyi gmhA mutant characterized in the present study expressed a LOS that migrated more rapidly in SDS-PAGE than the LOS of the wild-type parent strain. Moreover, the LOS of this H. ducreyi gmhA mutant also migrated more rapidly than the truncated LOS expressed by an rfaK (lbgB) mutant (60). Consistent with this rapid migration phenotype in SDS-PAGE, the LOS of the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant lost reactivity with MAb 3E6, which is directed against a surface-exposed epitope of H. ducreyi LOS (25). Expression of the H. ducreyi gmhA gene product in trans in E. coli χ711, a strain with a gmhA deletion, resulted in the synthesis of an LPS which migrated at a rate indistinguishable from that of the LPS of the E. coli parent strain. This same E. coli gmhA mutant was also complemented by the wild-type H. influenzae gmhA gene (8). It can be inferred from these data that the gmhA mutation in H. ducreyi resulted in the expression of a LOS molecule with a severely truncated oligosaccharide moiety and that the product of the H. ducreyi gmhA gene is a homolog of both the E. coli and the H. influenzae GmhA proteins.

Interestingly, the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant exhibited some changes in the relative abundances of a few major outer membrane proteins (Fig. 5), similar to the changes described for deep rough LPS mutants of enteric bacteria (19, 34, 40). Whether these modest alterations in protein expression could have affected virulence expression by the gmhA mutant cannot be determined directly from the available data. However, an isogenic momp mutant of H. ducreyi which lacked the ability to express one of the two OmpA-like major outer membrane proteins of this organism (33) was shown to be fully virulent in the temperature-dependent rabbit model (32a). This latter finding suggests that the observed changes in the relative abundances of the three outer membrane proteins in the gmhA mutant (Fig. 5) were not likely to have caused a reduction in virulence.

Southern blot analysis revealed that the gmhA gene is apparently well conserved among H. ducreyi strains. This finding is not surprising, especially in view of the fact that gmhA is known to be highly conserved among enteric bacteria (7). It is also interesting to note that the H. ducreyi gmhA gene, like the rfaK (lbgB) gene of this pathogen (21, 60), is not located within a cluster of other genes whose products are likely directly involved in LOS biosynthesis. The H. ducreyi rfaK (lbgB) gene is located adjacent to another gene (lbgA) whose expression is essential for the synthesis of wild-type LOS, but the H. ducreyi genes flanking the lbgAB genes do not encode proteins predicted to be involved in LOS expression (60). This situation is in contrast to the multiple, closely linked genes involved in enteric core LPS biosynthesis (i.e., the E. coli rfa genes) (32, 53). Similarly, the H. influenzae gmhA gene is not located among other LOS genes but instead is located between genes for two different ABC transport systems. Relative to gmhA in H. influenzae (47), several dpp genes essential for efficient dipeptide transport are located immediately upstream, whereas several art gene homologs, which are likely involved in arginine uptake, are located immediately downstream.

Complementation analysis (Fig. 6) was used to confirm that the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant did not possess a secondary mutation(s) which could have affected LOS expression. Analysis of the growth rate of this mutant indicated that, in broth medium in vitro, the absence of gmhA gene expression did not affect detectably either the rate or the extent of growth. In contrast, the absence of the gmhA gene product had a pronounced effect on H. ducreyi in vivo. In the temperature-dependent rabbit model, the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant was markedly less able than the wild-type parent strain to produce dermal lesions (Table 2). In addition, this same mutant could not be recovered from lesions at 7 days postinfection, whereas viable cells of the wild-type parent strain were present in almost all of the lesions sampled. Restoration of GmhA expression, accomplished by provision of the wild-type H. ducreyi gmhA gene in trans, resulted in a level of virulence equivalent to that obtained with the wild-type parent strain.

It has been well established that H. influenzae type b LOS mutants with altered (i.e., shortened) oligosaccharide chains usually exhibit decreased virulence in the infant rat model (13, 28, 31, 68). In fact, the H. influenzae type b isn (i.e., I69) mutant is one of the least virulent of all of the LOS mutants tested to date (28). The H. ducreyi gmhA mutant in the present study was also less virulent than its wild-type parent strain. This significant diminution in the virulence of the H. ducreyi gmhA mutant is in marked contrast to the effect of the rfaK (lbgB) mutation on the virulence of H. ducreyi (60). The H. ducreyi rfaK (lbgB) mutant possessed a less truncated LOS (21) (relative to that of the gmhA mutant) and did not exhibit a statistically significant reduction in virulence, although there was an apparent trend in this direction (60). While it could be inferred from these data that the extent of truncation of the LOS oligosaccharide moiety, as evidenced by LOS migration rate in SDS-PAGE, might be inversely related to virulence potential in H. ducreyi, results derived from virulence testing of LOS mutants of H. influenzae type b indicated the inherent inaccuracy of such a generalization (13, 28). Determination of whether the lack of GmhA expression has an effect on the virulence of H. ducreyi for humans will necessarily have to await testing of the gmhA mutant in the human challenge model for experimental chancroid (57, 58).

In conclusion, we have identified the H. ducreyi gmhA gene homolog. Expression of the gmhA gene product was shown to be essential for the synthesis of wild-type LOS by H. ducreyi. Insertional inactivation of the gmhA gene had an adverse effect on the virulence of H. ducreyi 35000 in the temperature-dependent rabbit model for experimental chancroid. The availability of this cloned gene and the related isogenic H. ducreyi mutant, together with the rfaK (lbgB) mutants of H. ducreyi (21, 60), should facilitate future studies on structure-function relationships within the oligosaccharide portion of H. ducreyi LOS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI-32011. B.A.B. was supported by U.S. Public Health Service training grant RR-07031.

E. coli χ705 and χ711 were generously provided by Roy Curtiss. The cat cartridge used in this study was constructed by Bruce A. Green. We thank Christine Ward and David Lewis for helpful discussions and for assistance with the animal model. We also appreciate the insights into the relationship between gmhA gene expression and LOS structure provided by Joanna Brooke.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed H J, Frisk A, Mansson J-E, Schweda E K H, Lagergard T. Structurally defined epitopes of Haemophilus ducreyi lipooligosaccharides recognized by monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3151–3158. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3151-3158.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfa M J, DeGagne P A, Totten P A. Haemophilus ducreyi hemolysin acts as a contact cytotoxin and damages human foreskin fibroblasts in cell culture. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2349–2352. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2349-2352.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Smith J A, Seidman J G, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Green Publishing Associates and Wiley Interscience; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barcak G J, Chandler M S, Redfield R J, Tomb J. Genetic systems in Haemophilus influenzae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:321–342. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brentjens R J, Ketterer M, Apicella M A, Spinola S M. Fine tangled pili expressed by Haemophilus ducreyi are a novel class of pili. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:808–816. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.808-816.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooke J S, Valvano M A. Biosynthesis of inner core lipopolysaccharide in enteric bacteria: identification and characterization of a conserved phosphoheptose isomerase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooke J S, Valvano M A. Molecular cloning of the Haemophilus influenzae gmhA (lpcA) gene encoding a phosphoheptose isomerase required for lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3339–3341. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3339-3341.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campagnari A A, Karalus R, Apicella M A, Melaugh W, Lesse A J, Gibson B W. Use of pyocin to select a Haemophilus ducreyi variant defective in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2379–2386. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2379-2386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campagnari A A, Wild L M, Griffiths G, Karalus R J, Wirth M A, Spinola S M. Role of lipopolysaccharides in experimental dermal lesions caused by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2601–2608. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2601-2608.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson S D B, Thomas C E, Elkins C. Cloning and sequencing of a Haemophilus ducreyi fur homolog. Gene. 1996;176:125–129. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cope L D, Lumbley S R, Latimer J L, Klesney-Tait J, Stevens M K, Johnson L S, Purven M, Munson R S, Jr, Lagergard T, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4056–4061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cope L D, Yogev R, Mertsola J, Argyle J C, McCracken G H, Jr, Hansen E J. Effect of mutations in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis genes on virulence of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2343–2351. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2343-2351.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtiss R, III, Charamella L J, Stallions D R, Mays J A. Parental functions during conjugation in Escherichia coli K-12. Bacteriol Rev. 1968;32:320–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMaria T F, Apicella M A, Nichols W A, Leake E R. Evaluation of the virulence of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae lipooligosaccharide htrB and rfaD mutants in the chinchilla model of otitis media. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4431–4435. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4431-4435.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon L G, Albritton W L, Willson P J. An analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of the Haemophilus ducreyi broad-host-range plasmid pLS88. Plasmid. 1994;32:228–232. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eidels L, Osborn M J. Phosphoheptose isomerase, first enzyme in the biosynthesis of aldoheptose in Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:5642–5648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkins C, Chen C-J, Thomas C E. Characterization of the hgbA locus encoding a hemoglobin receptor from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2194–2200. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2194-2200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferro-Luzzi Ames G, Spudich E N, Nikaido H. Protein composition of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: effect of lipopolysaccharide mutations. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:406–416. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.406-416.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, FitzHugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L-I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback R C, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Frichman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson B W, Campagnari A A, Melaugh W, Phillips N J, Apicella M A, Grass S, Wang J, Palmer K L, Munson R S., Jr Characterization of a transposon Tn916-generated mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi 35000 defective in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5062–5071. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5062-5071.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson B W, Melaugh W, Phillips N J, Apicella M A, Campagnari A A, Griffiss J M. Investigation of the structural heterogeneity of lipooligosaccharides from pathogenic Haemophilus and Neisseria species and of R-type lipopolysaccharides from Salmonella typhimurium by electrospray mass spectrometry. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2702–2712. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2702-2712.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond G W, Lian C J, Wilt J C, Ronald A R. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus ducreyi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;13:608–612. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.4.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen E J, Latimer J L, Thomas S E, Helminen M E, Albritton W L, Radolf J D. Use of electroporation to construct isogenic mutants of Haemophilus ducreyi. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5442–5449. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5442-5449.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen E J, Lumbley S R, Saxen H, Kern K, Cope L D, Radolf J D. Detection of Haemophilus ducreyi lipooligosaccharide by means of an immunolimulus assay. J Immunol Methods. 1995;185:225–235. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00118-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helander I M, Lindner B, Brade H, Altmann K, Lindberg A A, Rietschel E T, Zahringer U. Chemical structure of the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae strain I-69 Rd−/b+: description of a novel deep-rough chemotype. Eur J Biochem. 1988;177:483–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hennessy K J, Landolo J J, Fenwick B W. Serotype identification of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae by arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1155–1159. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1155-1159.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hood D W, Deadman M E, Allen T, Masoud H, Martin A, Brisson J R, Fleischmann R, Venter J C, Richards J C, Moxon E R. Use of the complete genome sequence information of Haemophilus influenzae strain Rd to investigate lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:951–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inzana T J, Corbeil L B. Development of a defined medium for Haemophilus somnus isolated from cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1987;48:366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura A, Gulig P A, McCracken G H, Jr, Loftus T A, Hansen E J. A minor high-molecular-weight outer membrane protein of Haemophilus influenzae type b is a protective antigen. Infect Immun. 1985;47:253–259. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.253-259.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura A, Hansen E J. Antigenic and phenotypic variations of Haemophilus influenzae type b lipopolysaccharide and their relationship to virulence. Infect Immun. 1986;50:69–79. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.1.69-79.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klena J D, Pradel E, Schnaitman C A. Comparison of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes rfaK, rfaL, rfaY, and rfaZ of Escherichia coli K-12 and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4746–4752. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4746-4752.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Klesney-Tait, J., and E. J. Hansen. Unpublished data.

- 33.Klesney-Tait J, Hiltke T J, Spinola S M, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. The major outer membrane protein of Haemophilus ducreyi consists of two OmpA homologs. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1764–1773. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1764-1773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koplow J, Goldfine H. Alterations in the outer membrane of the cell envelope of heptose-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:527–543. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.527-543.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lesse A J, Campagnari A A, Bittner W E, Apicella M A. Increased resolution of lipopolysaccharides and lipooligosaccharides utilizing tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Immunol Methods. 1990;126:109–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90018-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandrell R E, McLaughlin R, Kwaik Y A, Lesse A J, Yamasaki R, Gibson B, Spinola S M, Apicella M A. Lipopolysaccharides (LOS) of some Haemophilus species mimic human glycosphingolipids, and some LOS are sialylated. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1322–1328. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1322-1328.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melaugh W, Campagnari A A, Gibson B W. The lipooligosaccharides of Haemophilus ducreyi are highly sialylated. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:564–570. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.564-570.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melaugh W, Phillips N J, Campagnari A A, Tullius M V, Gibson B W. Structure of the major oligosaccharide from the lipooligosaccharide of Haemophilus ducreyi strain 35000 and evidence of additional glycoforms. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13070–13078. doi: 10.1021/bi00248a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nichols W A, Gibson B W, Melaugh W, Lee N-G, Sunshine M, Apicella M A. Identification of the ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose-6-epimerase (rfaD) and heptosyltransferase II (rfaF) biosynthesis genes from nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae 2019. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1377–1386. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1377-1386.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odumeru J A, Wiseman G M, Ronald A R. Role of lipopolysaccharide and complement in susceptibility of Haemophilus ducreyi to human serum. Infect Immun. 1985;50:495–499. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.495-499.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Odumeru J A, Wiseman G M, Ronald A R. Relationship between lipopolysaccharide composition and virulence of Haemophilus ducreyi. J Med Microbiol. 1987;23:155–162. doi: 10.1099/00222615-23-2-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer K L, Goldman W E, Munson R S., Jr An isogenic haemolysin-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi lacks the ability to produce cytopathic effects on human foreskin fibroblasts. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:13–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsons L M, Limberger R J, Shayegani M. Alterations in levels of DnaK and GroEL result in diminished survival and adherence of stressed Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2413–2419. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2413-2419.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patrick C C, Kimura A, Jackson M A, Hermanstorfer L, Hood A, McCracken G H, Jr, Hansen E J. Antigenic characterization of the oligosaccharide portion of the lipooligosaccharide of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2902–2911. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.2902-2911.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips N J, McLaughlin R, Miller T J, Apicella M A, Gibson B W. Characterization of two transposon mutants from Haemophilus influenzae type b with altered lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5937–5947. doi: 10.1021/bi960059b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preston A, Maskell D J, Johnson A, Moxon E R. Altered lipopolysaccharide characteristic of the I69 phenotype in Haemophilus influenzae results from mutations in a novel gene, isn. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:396–402. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.396-402.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Proctor R A, Denlinger L C, Bertics P J. Liposaccharide and bacterial virulence. In: Roth J A, Bolin C A, Brogden K A, Minion F C, Wannemuehler M J, editors. Virulence mechanisms of bacterial pathogens. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Purcell B K, Richardson J A, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. A temperature-dependent rabbit model for production of dermal lesions by Haemophilus ducreyi. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:359–367. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Purven M, Frisk A, Lonnroth I, Lagergard T. Purification and identification of Haemophilus ducreyi cytotoxin by use of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3496–3499. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3496-3499.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 52.San Mateo L R, Hobbs M M, Kawula T H. Periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase protects Haemophilus ducreyi from exogenous superoxide. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:391–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnaitman C A, Klena J D. Genetics of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in enteric bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:655–682. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.655-682.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schneider H, Schmidt K A, Skillman D R, van de Verg L, Warren R L. Sialylation lessens the infectivity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae MS11mkC. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1422–1427. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwan E T, Robertson B D, Brade H B, van Putten J P M. Gonococcal rfaF mutants express Rd2 chemotype LPS and do not enter epithelial host cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schweda E K H, Jonasson J A, Jansson P-E. Structural studies of lipooligosaccharides from Haemophilus ducreyi ITM 5535, ITM 3147, and a fresh clinical isolate, ACY1: evidence for intrastrain heterogeneity with the production of mutually exclusive sialylated or elongated glycoforms. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5316–5321. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5316-5321.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spinola S M, Orazi A, Arno J N, Fortney K, Kotylo P, Chen C-Y, Campagnari A A, Hood A F. Haemophilus ducreyi elicits a cutaneous infiltrate of CD4 cells during experimental human infection. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:394–402. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spinola S M, Wild L M, Apicella M A, Gaspari A A, Campagnari A A. Experimental human infection with Haemophilus ducreyi. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1146–1150. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stephens D S, McAllister C F, Zhou D, Lee F K, Apicella M A. Tn916-generated lipooligosaccharide mutants of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2947–2952. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2947-2952.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stevens M K, Klesney-Tait J, Lumbley S R, Walters K A, Joffe A M, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. Identification of tandem genes involved in lipooligosaccharide expression by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1997;65:651–660. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.651-660.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stevens M K, Porcella S, Klesney-Tait J, Lumbley S R, Thomas S E, Norgard M V, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. A hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein is involved in virulence expression by Haemophilus ducreyi in an animal model. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1724–1735. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1724-1735.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Templeton N S. The polymerase chain reaction: history, methods, and applications. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1992;1:58–72. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trees D L, Morse S A. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi: an update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:357–375. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsai C M, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharide in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tuffrey M, Alexander F, Ballard R C, Taylor-Robinson D. Characterization of skin lesions in mice following intradermal inoculation of Haemophilus ducreyi. J Exp Pathol. 1990;71:233–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tullius M V, Munson R S, Jr, Wang J, Gibson B W. Purification, cloning, and expression of a cytidine 5′-monophosphate N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase from Haemophilus ducreyi. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15373–15380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weiser J N, Williams A, Moxon E R. Phase-variable lipopolysaccharide structures enhance the invasive capacity of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3455–3457. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3455-3457.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zwahlen A, Rubin L G, Connelly C J, Inzana T J, Moxon E R. Alteration of the cell wall of Haemophilus influenzae type b by transformation with cloned DNA: association with attenuated virulence. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:485–492. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]