During 2013-2016, an estimated 2.4 million people in the United States were living with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. 1 With the availability of curative treatment since 2013, the United States has established a goal of eliminating hepatitis C as a public health threat by 2030. 2 HCV clearance cascades (hereinafter, HCV cascades) are an important tool to track progress toward elimination, across jurisdictions and at a national level, and to identify disparities in access to testing and treatment. HCV cascades are a sequence of steps that follow progression from testing and treatment to clearance and subsequent infection and can be used to inform public health interventions to facilitate progression along the cascade.

Many HCV cascades are developed in a single or regional health system in which both treatment and laboratory data are available. However, an important goal for health departments is to develop population-level cascades that capture data on HCV infection status for all people living in a jurisdiction who might seek care across various health settings. In the absence of treatment information, which is not always readily available in health department surveillance systems, HCV laboratory results can be used to develop HCV cascades. Here, we describe a standardized, laboratory result–based HCV cascade developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a guide for health departments (Figure 1, Supplemental Material).

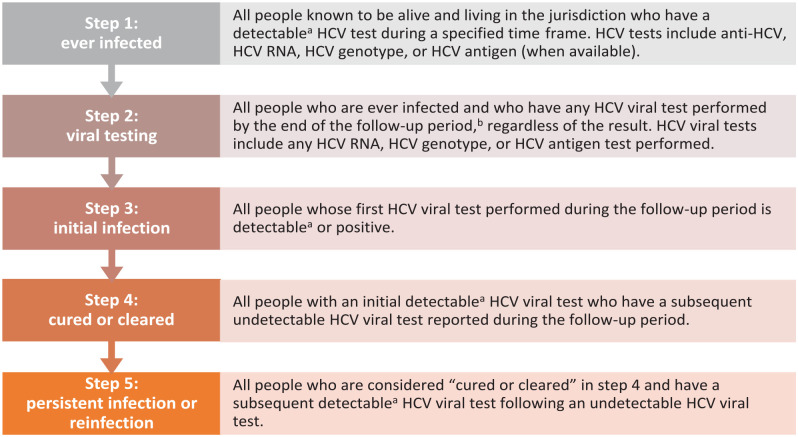

Figure 1.

Definitions for laboratory result–based hepatitis C virus (HCV) clearance cascade. Abbreviation: anti-HCV, HCV antibody.

a A detectable HCV viral test includes laboratory results that are detectable but below the limit of quantification.

b The follow-up period begins at the start of the time frame and extends 1 year beyond the time frame specified in step 1. This provides at least 1 additional year for people to have confirmatory viral testing, establish care, initiate and complete treatment (often 8-12 weeks), and complete posttreatment testing, which usually occurs 12 weeks after treatment completion.

Developing a Standardized, Laboratory Result–Based HCV Clearance Cascade for Public Health Jurisdictions

In 2019, the Tennessee Department of Health (TDH) developed a laboratory result–based HCV continuum of cure. 3 In 2020, CDC adapted the TDH approach to develop program guidance for health departments on how to construct a laboratory result–based HCV cascade (Figure 2). CDC solicited feedback on guidance from 8 health departments (Florida Department of Health, Kentucky Department for Public Health, Louisiana Department of Health, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, and TDH) and from the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists’ Hepatitis C Subcommittee. The laboratory result–based HCV cascade consists of 5 steps: ever infected, viral testing, initial infection, cured or cleared, and persistent infection or reinfection. Progression through each step in the HCV cascade is determined based on laboratory test results reported to the health department.

Figure 2.

Standardized hepatitis C virus (HCV) clearance cascade for public health departments. Measures A, C, and D outlined in black represent data-to-care opportunities.

Constructing a population-level HCV cascade requires a few minimum essential elements. Health departments must be able to receive, deduplicate, and track person-level longitudinal HCV laboratory test results from multiple health systems, health providers, public health laboratories, and commercial laboratories. Reportable laboratory results should include all reactive HCV antibody, detectable and undetectable HCV RNA, and, when available, detectable and undetectable HCV core antigen. Longitudinal HCV databases based on laboratory reports should include name, date of birth, sex, and test date at a minimum to allow for deduplication and matching and to conduct stratified analyses. While not required as part of this guidance, test dates could be used for additional analyses, such as calculating time to clearance. If possible, health departments should identify and remove people who have moved outside the jurisdiction and people who are known to have died, through linkage with other data sources, such as vital statistics records. Last reported address in the longitudinal HCV database can be used to determine residency status.

When available, additional data elements should be incorporated to identify disparities in HCV elimination. Reducing disparities in new viral hepatitis infections and along the HCV cascade is an objective of the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States. 2 Health departments can merge the longitudinal HCV database with internal data sources, such as HIV or cancer registries, or external data sources, such as electronic case reporting4,5 or Homeless Management Information Systems, 6 to incorporate demographic and risk factor information such as race, ethnicity, and housing status. Data sources for certain populations, such as state departments of corrections, Medicaid, or HIV surveillance systems, can be used to further describe HCV elimination progress in subpopulations.

Finding Data-to-Care Opportunities

The laboratory result–based HCV cascade measures 3 important data-to-care opportunities. Data-to-care opportunities are measurable steps that help to identify opportunities for public health action to improve progression along the HCV cascade. The first step is determining the proportion of people who were ever infected and who have had an HCV viral detection test reported—(step 2)/(step 1) (Figures 1 and 2). Viral testing is important to distinguish past infections that are previously cured or cleared (eg, HCV antibody reactive and HCV RNA undetectable) from current infections that require linkage to care and treatment (eg, HCV RNA detectable). Health departments should work to maximize viral testing, as this is a critical step to confirm current infection before starting HCV treatment. CDC has a goal to increase the proportion of HCV antibody tests that include reflex HCV viral testing (automatic laboratory testing for RNA on the same specimen after a reactive HCV antibody test result), by encouraging additional HCV-specific provider education and identifying solutions for commercial and hospital-based laboratories to increase HCV RNA reflex testing.

The second data-to-care opportunity is the proportion of HCV viremic infections present at the beginning of the time frame that have been cured by treatment or have naturally cleared by the end of the time frame—(step 4)/(step 3). In defining cured or cleared, CDC’s laboratory result–based HCV cascade builds on and simplifies previously published population-level HCV cascades by incorporating modifications to align closely with more recent, simplified treatment guidelines. 7 Some HCV cascades have defined cure by using sustained virologic response (SVR) as determined by HCV viral testing at least 12 weeks after treatment completion. 8 When data to determine treatment end dates are not available, other HCV cascades have defined cure by using sequential HCV viral test results. 9 In contrast, CDC’s HCV clearance cascade defines cured or cleared as a single undetectable HCV viral test following a prior detectable HCV viral test result. This definition simplifies the algorithmic data-processing tasks for health departments and categorizes all people who have a documented undetectable HCV viral test as being cured or cleared. Notably, this category does not distinguish between treatment-associated and natural viral clearance and does not capture data on people who do not return for follow-up testing. Prevention activities to maximize the proportion of people who are cured or cleared include improving linkage to care (eg, patient navigation, same-day access to treatment initiation), increasing the number of trained HCV treatment providers, and removing administrative or policy barriers to treatment (eg, Medicaid restrictions for sobriety, fibrosis, specialist providers, or prior authorization policies). 10

The third data-to-care opportunity is the proportion of people who were cured or cleared during the evaluation time frame who demonstrate persistent infection or reinfection—(step 5/step 4). Persistent infection or reinfection is defined as a subsequent detectable HCV viral test following an undetectable HCV viral test. Persistent infection refers to instances in which a transient, undetectable RNA is reported early in the treatment course but SVR after 12 weeks posttreatment is not achieved, either because of incomplete treatment or treatment failure. Reinfection refers to a subsequent infection that occurs after SVR was achieved during the immediate prior HCV infection. Opportunities to prevent these outcomes, particularly reinfections, include engaging substance use treatment and harm reduction programs and improving access to sterile drug injection equipment.

Supporting Health Departments to Implement Laboratory Result–Based HCV Cascades

CDC has distributed the laboratory result–based HCV cascade program guidance to 59 health departments funded under CDC’s Integrated Viral Hepatitis Surveillance and Prevention Funding for Health Departments cooperative agreement. As part of the 5-year cooperative agreement, funded health departments are expected to develop a laboratory result–based HCV cascade. This funding also supports health departments to improve completeness of demographic data and to engage laboratories to assess current practices and adopt reflex HCV viral testing. CDC assessed health department capacity to develop a laboratory result–based HCV cascade at the beginning of the funding period. Among 59 health departments that responded in the initial year of funding, 28 (47%) health departments have a longitudinal surveillance registry for chronic HCV infection (unpublished data, CDC, 2021). Because undetectable HCV RNA reporting is critical to defining steps 2 and 4, CDC also surveyed jurisdictions about the completeness of HCV RNA reporting. Overall, among 58 health departments that responded, 15 (26%) health departments self-reported receiving all undetectable HCV RNA results, 33 (57%) self-reported receiving some undetectable HCV RNA results, and 10 (17%) self-reported that undetectable HCV RNA results were not received (unpublished data, CDC, 2021).

This laboratory result–based HCV cascade has several limitations. First, because nonreactive HCV antibody test results are not reportable in most jurisdictions, the HCV cascade is unable to assess the number of people who have been screened for HCV (all HCV antibody tests performed), which would be useful to measure progress in implementing universal HCV screening. Therefore, the cascade begins with people diagnosed with HCV infection. 11 Second, people who complete treatment and do not return for posttreatment testing might not have a documented undetectable HCV RNA test result. Because treatment leads to cure in most people, the cascade might underestimate the proportion of the population with HCV viremia who have been cured or cleared. Third, without treatment data, it is difficult to distinguish between spontaneously cleared HCV infection and treatment cure. For this reason, the HCV cascade is intentionally titled a clearance cascade rather than a cure cascade. However, this distinction has little importance at a population level, because the primary actionable step is to link all people with detectable HCV RNA to treatment. Fourth, the laboratory result–based HCV cascade cannot distinguish between persistent infection (eg, incomplete treatment, treatment failure) and reinfection; thus, step 5 should not be interpreted as the proportion of people with reinfection. Additional validation studies are needed to determine whether laboratory test dates could be used to differentiate cured from cleared infections or persistent infections from reinfections. Lastly, recording data on race and ethnicity from laboratory-based reporting and identifying people who have moved or died outside the jurisdiction is challenging. Laboratory testing results rarely include data on race and ethnicity. Legal authority for recording deaths resides with states, and a single publicly accessible, searchable, national death system does not exist. Data integration with other databases or electronic health records, as discussed previously, is needed to improve data completeness.

Public Health Implications

CDC has developed program guidance on laboratory result–based HCV cascades for health departments to support HCV elimination efforts. Health departments have begun constructing HCV cascades to track progress toward HCV elimination. With further improvements in data quality, HCV cascades can also measure disparities in access to testing and treatment for hepatitis C. CDC is supporting these efforts through its 5-year integrated funding cooperative agreement. Additional progress remains to strengthen electronic laboratory and case reporting, develop longitudinal HCV surveillance systems, and expand undetectable HCV RNA reporting in all jurisdictions. US jurisdictions can now implement a standardized approach to measure the impact of elimination efforts and ensure that all people have access to HCV testing and effective hepatitis C treatment.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-phr-10.1177_00333549231170044 for Development of a Standardized, Laboratory Result–Based Hepatitis C Virus Clearance Cascade for Public Health Jurisdictions by Martha P. Montgomery, Lindsey Sizemore, Heather Wingate, William W. Thompson, Eyasu Teshale, Ade Osinubi, Mona Doshani, Noele Nelson, Neil Gupta and Carolyn Wester in Public Health Reports

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Florida Department of Health, Kentucky Department for Public Health, Louisiana Department of Health, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, and Tennessee Department of Health for reviewing and providing feedback on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) laboratory result–based hepatitis C virus clearance cascade guidance for local and state health departments. The authors also acknowledge Noreen Kloc, MPH; Karon Lewis, DrPH, MS; and Laurie Barker, MSPH, from CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis, for providing data on health department capacity assessment.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Martha P. Montgomery, MD, MHS  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9392-9294

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9392-9294

Lindsey Sizemore, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6187-7370

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6187-7370

Heather Wingate, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3244-2052

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3244-2052

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online. The authors have provided these supplemental materials to give readers additional information about their work. These materials have not been edited or formatted by Public Health Reports’s scientific editors and, thus, may not conform to the guidelines of the AMA Manual of Style, 11th Edition.

References

- 1. Hofmeister MG, Rosenthal EM, Barker LK, et al. Estimating prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 2013-2016. Hepatology. 2019;69(3):1020-1031. doi: 10.1002/hep.30297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Viral hepatitis: national strategic plan for the United States: a roadmap to elimination, 2021-2025. 2020. Accessed March 8, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Viral-Hepatitis-National-Strategic-Plan-2021-2025.pdf

- 3. Sizemore LA, Wingate H, Black J, Wester CN. Tennessee’s 2017 hepatitis C virus continuum of cure. Abstract presented at: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists Annual Conference; June 4, 2019; Raleigh, North Carolina. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://cste.confex.com/cste/2019/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/11007 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mishra N, Duke J, Karki S, et al. A modified public health automated case event reporting platform for enhancing electronic laboratory reports with clinical data: design and implementation study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(8):e26388. doi: 10.2196/26388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Michaels M, Syed S, Lober WB. Blueprint for aligned data exchange for research and public health. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(12):2702-2706. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocab210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biederman DJ, Callejo-Black P, Douglas C, et al. Changes in health and health care utilization following eviction from public housing. Public Health Nurs. 2022;39(2):363-371. doi: 10.1111/phn.12964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. 2022. Accessed February 22, 2023. http://www.hcvguidelines.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Baer A, Fagalde MS, Drake CD, et al. Design of an enhanced public health surveillance system for hepatitis C virus elimination in King County, Washington. Public Health Rep. 2020;135(1):33-39. doi: 10.1177/0033354919889981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore MS, Bocour A, Laraque F, Winters A. A surveillance-based hepatitis C care cascade, New York City, 2017. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(4):497-501. doi: 10.1177/0033354918776641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou K, Fitzpatrick T, Walsh N, et al. Interventions to optimise the care continuum for chronic viral hepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):1409-1422. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30208-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schillie S, Wester C, Osborne M, Wesolowski L, Ryerson AB. CDC recommendations for hepatitis C screening among adults—United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69(2):1-17. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6902a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-phr-10.1177_00333549231170044 for Development of a Standardized, Laboratory Result–Based Hepatitis C Virus Clearance Cascade for Public Health Jurisdictions by Martha P. Montgomery, Lindsey Sizemore, Heather Wingate, William W. Thompson, Eyasu Teshale, Ade Osinubi, Mona Doshani, Noele Nelson, Neil Gupta and Carolyn Wester in Public Health Reports