Abstract

Background:

Decedents with late-life dementia are often found at autopsy to have vascular pathology, cortical Lewy bodies, hippocampal sclerosis, and/or TDP-43 encephalopathy alone or with concurrent Alzheimer lesions. Nonetheless it is commonly believed that Alzheimer neuropathologic changes (NC) are the dominant or exclusive drivers of late-life dementia.

Objectives:

Assess associations of end-of-life cognitive impairment with any one or any combination of five distinct NC. Assess impairment prevalence among subjects having natural resistance to each type of NC.

Methods:

Brains from 1040 autopsied participants of the Honolulu-Asia Study, the Nun Study, and the 90 + Study were examined for NC of Alzheimer disease, Lewy body dementia, microvascular brain injury, hippocampal sclerosis, and limbic predominate TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE). Associations with impairment were assessed for each NC and for NC polymorbidity (variable combinations of 2-5 concurrent NC).

Results:

Among 387 autopsied decedents with severe cognitive impairment 20.4% had only Alzheimer lesions (ADNC), 25.3% had ADNC plus 1 other NC, 11.1% had ADNC plus 2 or more other NC, 28.7% had no ADNC but 1-4 other NC, and 14.5% had no/negligible NC. Combinations of any two, three, or four NC were highly frequent among the impaired. Natural resistance to ADNC or any other single NC had a modest impact on overall cohort impairment levels.

Conclusions:

Polymorbidity involving 1-5 types of concurrent NC is a dominant neuropathologic feature of ADRD. This represents a daunting challenge to future prevention and could explain failures of prior preventive intervention trials and of efforts to identify risk factors.

INTRODUCTION

Most cases of dementia in late life are diagnosed as probable or possible Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as defined by diagnostic criteria established in 1984.1 More recently It has become accepted that clinical Alzheimer’s disease may be mimicked by a variety of other dementing diseases, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as diagnostic multimorbidity. During the past two decades a large number of clinical-pathologic studies linking late onset dementia with brain changes found at autopsy have consistently demonstrated that most persons assigned that diagnosis have brain lesions distinct from or in addition to AD amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT).2-19 This has led to a nosologic shift toward “Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias” (ADRD).

Despite a growing appreciation of the diagnostic multimorbidity of late onset dementia, hundreds of preventive intervention trials, eager participation by thousands of volunteers, and investments of many millions of private and taxpayer dollars have been based on an implicit understanding of late life dementia as exclusively or predominantly linked to neocortical accumulations of A-beta amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles. Very few of these trials have shown even marginal impacts on subsequent cognitive decline.

Ten years ago a panel of 16 eminent neuropathologists recommended diagnostic criteria for definite AD as part of a package that included criteria for three other diseases: Lewy body disease (LBD), microvascular brain injury (uVBI), and hippocampal sclerosis (HS), each with characteristic brain lesions.6,7 Each type of lesion is conventionally viewed by neuropathologists as a diagnostically distinct neuropathologic change (NC). Seminal elements emerging from this group effort were: (i) diagnoses of definite AD and the other specific diseases may be made with or without cognitive impairment, and (ii) multiple concurrent diseases are permissible. This means that individuals who had appeared normal during life might nonetheless be diagnosed as having AD and/or other disease(s), and that a specific illness (dementia) might be attributed to multiple individual or concurrent diseases. A fifth dementia-associated pathology, limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) was subsequently recognized as an additional neuropathologic abnormality linked to dementia.17

Several distinct dementing illnesses are known to mimic the clinical features or probable or possible Alzheimer’s disease. It is also clear that late life dementia may involve mixed concurrent conditions rather than any single disease.20-26 The NC observed in these diverse illnesses have consistently included classical ADNC (amyloid beta plaques and NFT), uVBI NC (microvascular focal ischemic lesions), limbic and neocortical LBD NC (Lewy bodies and neurites), HS NC (hippocampal sclerosis), and LATE NC (limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy). Each is presumed the result of its own unique pathogenic process, time course, and risk factors. Their high frequencies, individual associations with dementia and common co-occurrence are well accepted by the neuropathology research community.

In this report we summarize more than two decades of epidemiologic and neuropathologic research in three cohorts: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study (HAAS), Nun Study (NS), and the 90+ Study. Neuropathologic and cognition observations are presented for 1,040 individual research participants of diverse age, sex, education, and ethnicity. The consistency of observations and correspondence among them and with other studies implies their representativeness of the general population.

METHODS

Study designs, methods, and participants.

The data were from three longitudinal cohort studies that have been fully described in prior reports.4,10,14,20,21,25,26,29,31 The Nun Study cohort consisted of Catholic Sisters mostly from midwestern and southeastern United States who were members of the School Sisters of Notre Dame. The HAAS participants were Japanese-American men born 1900 through 1919 who lived on Oahu when recruited in 1965 as participants of the Honolulu Heart Program, and who then continued as HAAS subjects from 1992 through 2012. The 90+ Study cohort included mostly Caucasian men and women aged 90 years and older at enrollment beginning in 2003, most of whom were survivors from the earlier Leisure World Cohort Study initiated in the early 1980s in a southern California retirement community. Participants of all three cohorts were followed at intervals with neurological and physical examinations, cognitive testing, and functional assessments. Informed consents, institutional approvals, and instruments used for cognitive and other testing have been fully described in prior reports. Procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the originating institutions. Participants, their designated surrogates, and legal next of kin provided consent to participate, for conduct of an autopsy, and use of findings for continuing analyses. Data collection and neuropathologic measures were designed, defined, managed, and held constant through the two decades of all three projects.

Dementing disease lesions -- binarized neuropathologic change (NC) variables.

Each disease is marked by its specific NC. Alzheimer’s NC (ADNC) = 1 if Braak stage V or VI, or if neocortical neuritic plaque density was moderate or severe and Braak stage was IV; all others = 0 (negligible). Microvascular brain injury NC (uVBI NC) = 1 if two or more microinfarcts were counted across all H&E-stained brain sections; all others = 0. Lewy body dementia NC (LBD NC) = 1 if abundant diffuse cortical alpha-synuclein positive Lewy bodies were observed; all others = 0. Hippocampal sclerosis NC (HS NC) = 1 if typical changes were identified bilaterally or unilaterally; not observed=0. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy NC (LATE NC) = 1 if limbic or neocortical inclusions were identified; all other = 0. Because HS NC and LATE NC were frequently associated, we have chosen for this report to identify them as three separate variables: pure HS NC, pure LATE NC, and mixed LATE-HS NC. An NC value of 1 indicates severity sufficient to approximately double the likelihood of severe cognitive impairment or dementia compared with cohort peers with lesser severities of the same NC. An NC value = 0 is assigned when the NC is not observed or present at lesser severity. Each individual’s total neuropathology burden was calculated by adding the individual NC values. Neuropathologic lesion definitions and reading/scoring protocols for all three projects were nearly identical and were determined by two senior neuropathologists, William Markesbery (deceased) and Thomas Montine who worked closely to ensure consistency at all three sites.

Assessments to identify individuals as cognitively unimpaired, mildly/moderately impaired, or severely impaired or demented at final examination.

These correspond closely with the commonly used clinical categories of normal cognition, cognitively impaired but not demented (CIND), and demented. For HAAS these were based on each participant’s final Cognitive Assessment and Screening Instrument (CASI) score with values 74-100 = unimpaired, 60-73.9 = mild/moderate impairment, and 0-59.9 = severe impairment.27 For NS, final assignments were based on total scores achieved on the full Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) test battery administered at the final examination with values 66-100 = unimpaired, 33-65 = mild/moderate impairment, and 0-32 = severe impairment. For the 90+ Study a cognitive diagnosis (no cognitive impairment, mild cognitive impairment without dementia, or dementia/severe impairment) was assigned after death by a multidisciplinary consensus committee panel blinded to neuropathologic diagnoses but using all available clinical information that included bi-annual physical and neuropsychological evaluations, review of medical history, medical records, and clinical brain imaging when available.

Construction of Figure 1.

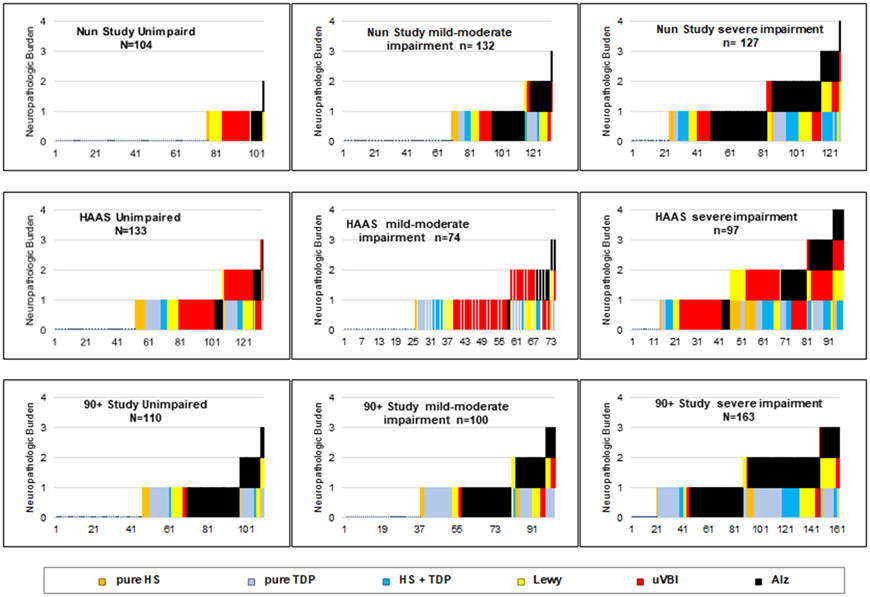

FIGURE. Neuropathologic changes in 1,040 autopsied study participants showing types and frequencies of co-morbid lesion occurrence.

These 9 graphs demonstrate frequencies of 5 types of neuropathologic change (i.e. types of brain lesion) for 1,040 autopsied individuals grouped according to their cohort and end-of-life cognitive status. One slender stacked component bar is shown for each individual. Each bar is comprised of 0-4 components indicating the lesions observed in that individual’s brain. The height of each bar indicates the total neuropathology burden for that brain. The left to right order in each graph’s horizontal axis was generated by presorting based on neuropathologic change frequencies and total neuropathology burden in order to demonstrate patterns of association of lesion types and total burden with cognitive status.

Essential brain lesion data for all 1,040 decedent subjects are presented graphically after imposing a left to right ordering of individuals according to their lesion types and severities by serial sorting first based on their separate NC values and then on total neuropathologic burdens. Further explanation is provided in the legend and results section.

Human and/or animal experimention.

None occurred in the conduct or analyses of the work described here.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of participants in the three cohorts. Substantial differences in ages, education, sex, and ethnicity are apparent.

Table 1.

Personal Characteristics of Study Participants in each Cohort

| Characteristic | HAAS | Nun Study | 90+ Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=304 | n=363 | n=373 | |

| Sex (female / male) | 0 / 304 | 363 / 0 | 252 / 121 |

| Age at death (year, mean) | 90 | 91 | 98 |

| Education | |||

| less than high school (%) | 46 | 9 | 5 |

| completed college (%) | 13 | 87 | 52 |

| Ethnicity: | |||

| Caucasian (%) | 0 | >99 | 99 |

| Japanese-American (%) | 100 | 0 | <1 |

| Other ethnicity (%) | 0 | <1 | <1 |

| APOE e4 positive (%) | 22 | 23 | 20 |

| Severe cognitive impairment (%) | 32 | 35 | 44 |

Immuno-histopathologic brain autopsy results are shown in the figure for all 1,040 cohort participants. Data are presented in the figure as stacked bars, one slender bar for each autopsied participant. The height of each bar corresponds to the total neuropathology burden for that brain. The types of NC are distinguished by color: black for ADNC, red for uVBI NC, yellow for LBD NC, light blue for pure LATE NC, orange for pure HS NC, and dark blue for mixed LATE/HS NC. For example, a bar with three stacked components, red, black, and yellow, indicates a brain in which three NC were observed: uVBI NC, ADNC, and LB NC.

Each NC is understood as demonstrating (and establishing a diagnosis of) its specific disease. Each co-morbid disease is presumed to contribute approximately equally to the participant’s dementia. The rainbow of colors in the figure shows a striking co-morbid disease heterogeneity with substantial variation in mixtures among the three cohorts.

Among HAAS cohort members uVBI were the most frequent NC. LATE NC and ADNC were more common in the 90+ participants. LBD NC were seen in all three cohorts but were less frequent among 90+ participants. ADNC were seen in about half of the NS and 90+ Study brains, usually in combination with one or two of the other types of NC. Except for a moderate association of HS NC with LATE NC and a weak association between ADNC and LBD NC, the NC were not substantially associated one with another, supporting a presumption that they represent distinct pathogeneses without substantially shared determinants. The supplementary materials provides a Spearman correlation matrix showing associations among and between the NC, and with ages at death for the 1040 participants of the three cohorts.

Among the 1,040 total participants from the three cohorts, 347 had been cognitively unimpaired at final testing. Of the unimpaired, 174 (50.1%) had negligible brain lesions, 133 (38.3%) had one NC, 36 (10.4%) had two NC types, and 4 (1.1%) had three or more concurrent NC types. Among the 387 participants with severe cognitive impairment, 55 (14%) had no/negligible NC, 155 (40%) had only one NC type, 132 (34%) had two NC types, and 45 (12%) had three or more concurrent types of NC. About 86% of the dementia cases were linked to one or a combination of these five specific types of NC, leaving 14% neuropathologically unexplained.

The values and the row percentages shown in Table 2 demonstrate marked increases in end-of-life severe cognitive impairment (and the improbability of being cognitively unimpaired) with greater total neuropathologic burdens. Burdens of 1 were often observed in the brains of decedents who had been unimpaired while values of 2 or greater were frequent among those with severe impairment. The prevalence of end-of-life severe cognitive impairment increased continuously from approximately 14% among decedents with no/negligible NC to 80-95% in decedents with more than two concurrent NC types.

Table 2.

Neuropathology Burden Showing Ages at Death and Frequencies of End-of-Life Cognitive Impairment

| Cohort and NC Burden | n | Age at Death (mean years) |

Unimpaired n (%) |

Mild/Moderate Impairment n (%) |

Severe Impairment/demented n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAAS | |||||

| Negligible neuropathology | 90 | 90 | 52 (58) | 25 (28) | 13 (14) |

| One NC, any type | 120 | 91 | 55 (46) | 33 (28) | 32 (27) |

| Two NC, any combination | 73 | 89 | 24 (33) | 14 (19) | 35 (48) |

| Three or more, any combination | 21 | 92 | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | 17 (81) |

| Totals: | 304 | 133 (44) | 74 (24) | 97 (32) | |

| Nun Study | |||||

| Negligible neuropathology | 162 | 91 | 76 (47) | 64 (39) | 22 (14) |

| One NC, any type | 130 | 91 | 27 (21) | 47 (36) | 56 (43) |

| Two NC, any combination | 58 | 91 | 1 (2) | 20 (33) | 37 (65) |

| Three or more, any combination | 13 | 91 | 0 | 1 (8) | 12 (92) |

| Totals: | 363 | 104 (29) | 132 (36) | 127 (35) | |

| 90+ Study | |||||

| Negligible neuropathology | 102 | 98 | 46 (45) | 36 (35) | 20 (20) |

| One NC, any type | 161 | 98 | 51 (32) | 43 (27) | 67 (41) |

| Two NC, any combination | 87 | 98 | 11 (13) | 16 (18) | 60 (69) |

| Three or more, any combination | 23 | 98 | 2 (9) | 5 (22) | 16 (70) |

| Totals: | 373 | 110 (30) | 100 (27) | 163 (44) | |

Row percentages demonstrate relationship of total neuropathologic burden to final cognitive state.

Table 3 compares individuals with severe cognitive impairment, with mild/moderate impairment, or who were unimpaired in their final years with regard to frequencies of the 6 categories of brain lesion types. ADNC were seen in approximately half of those with severe cognitive impairment, leaving half with no linkages to Alzheimer pathology. Slightly more than half of the brains with ADNC had one or more concurrent non-Alzheimer NC. These observations belie the common belief that amyloid and tau-positive inclusions are responsible for the great majority of ADRD cases. Classical Alzheimer brain lesions by themselves (i.e., without concurrent non-Alzheimer lesions) are not the usual proximate causal event associated with severe impairment.

Table 3.

Relationship of Final Cognitive State to Alzheimer Disease Neuropathologic Change (ADNC) and non-ADNC

| Cohort | n | Negligible NC n (%) |

Pure ADNC n (%) |

ADNC plus 1 non-ADNC n (%) |

ADNC plus >=2 non-ADNC n (%) |

No ADNC 1 non-ADNC n (%) |

No ADNC 2 or more non-ADNC n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAAS | |||||||

| Unimpaired | 133 | 52 (39) | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) | 50 (38) | 20 (15) |

| Mild/Moderate Impairment | 74 | 25 (34) | 1 (1) | 5 (7) | 2 (3) | 32 (43) | 9 (12) |

| Severe Impairment | 97 | 13 (13) | 4 (4) | 12 (12) | 16 (17) | 28 (29) | 24 (25) |

| Nun Study | |||||||

| Unimpaired | 104 | 76 (73) | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 21 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Mild/Moderate Impairment | 132 | 64 (48) | 25 (19) | 16 (12) | 1 (1) | 25 (17) | 4 (3) |

| Severe Impairment | 127 | 22 (17) | 35 (28) | 34 (27) | 12 (9) | 21 (17) | 3 (2) |

| 90+ Study | |||||||

| Unimpaired | 110 | 46 (42) | 28 (25) | 11 (10) | 2 (2) | 23 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Mild/Moderate Impairment | 100 | 36 (36) | 24 (24) | 14 (14) | 5 (5) | 19 (19) | 2 (2) |

| Severe Impairment | 163 | 20 (12) | 41 (25) | 56 (35) | 15 (9) | 26 (16) | 5 (3) |

Row percentages demonstrate relationships of final cognitive state with frequencies of single and multiple NC.

As is apparent in Tables 2 and 3, the total neuropathology burden was strongly related to severe cognitive impairment regardless of which NC types were involved. This conclusion is powerfully supported by logistic and linear regression analyses presented in the supplementary materials. The logistic models allow a comparison of odds ratios (for dementia) associated with the six individual NCs, with those associated with a simple count of the number of different types of NC observed in each brain (one variable with values 0, 1, 2, or more than 2) without regard to which specific NC were involved. This single 3-level measure of total neuropathologic burden was nearly as strongly linked to dementia as the combined set of 6 individual NCs. To demonstrate the exponentially additive influences of multiple concurrent NC, we then generated three “dummy” variables representing 3 levels of increasing total burden; one for brains showing a single NC of any type, a second for brains with two NC of any NC type, and a third for brains with three or more NC of any type. In logistic models that included education, age at death and these three dummy variables we demonstrated a dramatic, exponential increase in odds ratios for dementia across the three levels of increasing burden, using a burden of zero NCs as the reference category. Very similar results in all three cohorts are shown in the supplementary materials.

We interpret these results as suggesting that clinical dementia in late life typically reflects the logistically (exponentially) summed influences of disparate brain injuries distributed across separate gray and/or white neural systems by single or multiple independent but effectively convergent dementing diseases. This inference is consistent with the well-known aphorism that the clinical manifestations of a brain abnormality tend to depend more on “where” rather than “what” it is. This interpretation implies that fully effective future preventive interventions of ADRD may well require simultaneous reductions of multiple NC, rather than of any one NC (including ADNC) or of any specific combination of two.

Relevance to Prevention

Rational strategies for preventing an illness like dementia must be based on an understanding of (or an informed guess at) its etiology, pathogenesis, and its initiating and proximate events. Our findings suggest that ADRD appears most commonly in individuals whose brains show variable constellations of independent but concurrent dementing diseases. The pathophysiologic cascades responsible for each disease and its characteristic brain NC may be initiated well before onset of symptoms, and then modulated to histopathologic maturity by constitutional characteristics and a succession of variable exposures. Opportunities for prevention may exist at multiple points throughout the pathogenic beginnings and progression of each disease.

If an intervention were fully successful in blocking, preventing, or ablating neocortical amyloid plaques and NFT without altering other processes and their neuropathologic manifestations, what might be the expected reduction in risk of dementia? While this question cannot be directly addressed with available data, our cohort studies provide a resource for informed speculation. We speculate that the frequency of late-life dementia in individuals who had been protected by a totally effective intervention against ADNC might approximate that observed in their peers who were fully resistant to the same pathological brain changes, i.e., those who “naturally” lacked the classical brain lesions of AD.29 A comparison of dementia occurrence in such AD-resistant participants with that in their full cohort could provide an estimate of the maximum reduction in dementia one might expect from an intervention that completely prevented the development of Alzheimer pathology.

In Table 4 we present observed end-of-life frequencies of severe cognitive impairment for several subsets of each cohort. One subset was characterized by total “natural” resistance to the development of AD (i.e., with negligible ADNC at autopsy). This approach may provide an optimistic expectation for dementia prevention since it excludes not just the adverse influences of AD, but also those of whatever co-morbid NC existed in those same individuals. Additional naturally resistant subsets were defined by excluding individuals with each of the other types of NC. Each subset differed from the full cohort by virtue of its exclusion of individuals in whose brain one specific type of dementia-associated NC was identified at autopsy, retaining all others.

Table 4.

End of Life Cognitive Function Categories in Full Cohorts and in Subsets with Negligible Levels of Selected Types of Neuropathologic Change (NC)

| Cohorts and Selected Subsets | Total n |

Unimpaired n (%) |

Mild/ Moderate impairment n (%) |

Moderate/Severe Impairment n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAAS | ||||

| full cohort | 304 | 133 (44) | 74 (24) | 97 (32) |

| subset with negligible ADNC | 253 | 122 (48) | 66 (26) | 65 (26) |

| subset with negligible uVBI NC | 168 | 87 (52) | 42 (25) | 39 (23) |

| subset with negligible neocortical and limbic LBD NC | 259 | 117 (45) | 66 (26) | 76 (29) |

| subset with negligible LATE NC | 226 | 105 (46) | 58 (26) | 63 (28) |

| subset with negligible HS NC | 248 | 117 (47) | 64 (26) | 67 (27) |

| subset with negligible ADNC and uVBI NC | 147 | 80 (54) | 38 (26) | 29 (20) |

| subset with negligible ADNC and Lewy NC | 217 | 107 (49) | 59 (27) | 51 (24) |

| subset with negligible NC, all types | 90 | 52 (58) | 25 (28) | 13 (14) |

| Nun Study | ||||

| full cohort | 363 | 104 (29) | 132 (36) | 127 (35) |

| subset with negligible ADNC | 233 | 97 (42) | 90 (38) | 46 (20) |

| subset with negligible uVBI NC | 315 | 90 (28) | 119 (38) | 106 (34) |

| subset with negligible neocortical and limbic LBD NC | 320 | 97 (30) | 120 (38) | 103 (32) |

| subset with negligible LATE NC | 310 | 104 (34) | 115 (37) | 91 (29) |

| subset with negligible HS NC | 324 | 103 (32) | 120 (37) | 101 (31) |

| subset with negligible ADNC and uVBI NC | 201 | 83 (41) | 80 (40) | 38 (19) |

| subset with negligible ADNC and Lewy NC | 214 | 91 (40) | 84 (39) | 39 (18) |

| subset with negligible NC, all types | 162 | 76 (47) | 64 (39) | 22 (14) |

| 90+ Study | ||||

| full cohort | 373 | 110 (29) | 100 (2) | 163 (44) |

| subset with negligible ADNC | 177 | 69 (39) | 57 (32) | 51 (29) |

| subset with negligible uVBI NC | 355 | 108 (30) | 95 (26) | 152 (43) |

| subset with negligible neocortical and limbic LBD NC | 320 | 100 (31) | 88 (27) | 132 (41) |

| subset with negligible LATE NC | 256 | 90 (35) | 75 (29) | 91 (35) |

| subset with negligible HS NC | 330 | 102 (30) | 94 (28) | 134 (41) |

| subset with negligible ADNC and uVBI NC | 169 | 67 (39) | 56 (33) | 46 (27) |

| subset with negligible ADNC and Lewy NC | 160 | 63 (39) | 52 (32) | 45 (28) |

| subset with negligible NC, all types | 102 | 46 (45) | 36 (35) | 20 (20) |

Row frequencies and percentages show distribution across levels of cognitive impairment

In the HAAS, 32% of the full cohort developed severe cognitive impairment while 26% of the subset “naturally” resistant to ADNC developed severe cognitive impairment, representing a 19% lesser lifetime occurrence of dementia. In the NS, 35% of the full cohort and 20% of the subset “naturally” lacking ADNC developed severe impairment before death, providing a best estimate that a fully effective AD intervention might reduce the end-of-life prevalence of dementia by about 43%. In the 90+ Study, 44% of the full cohort developed dementia while 29% of the subset “naturally” resistant to development of ADNC developed dementia, representing a 34% lowering of the lifetime development of dementia.

Table 4 also provides estimates of expected reductions in end-of-life dementia prevalence levels that might be achieved with complete lifetime prevention of each of the other four dementing diseases. In the HAAS cohort a total prevention of uVBI is predicted to result in a 28% reduction in lifetime dementia prevalence, reflecting the higher frequency of microvascular lesions in this cohort. This is remarkably close to our previously reported HAAS estimate of 27% of cases of dementia being attributable to ineffectively treated middle life hypertension.31 The enormous importance of effective treatment of hypertension in middle and late life as a means for preventing dementia and cognitive decline is further supported by results from the SPRINT MIND clinical trial.32

Proportions of participants with negligible levels of all five types of dementia-associated brain lesions were 29.6% for HAAS (90/304), 44.6% for NS (162/363), and 27.3% for the 90+ Study (102/373). Frequencies of end-of-life dementia in these global NC resistant subsets were 14.4% for HAAS (13/90), 13.6% for NS (22/162) and 19.6% in the 90+ Study (20/102). Even with fully effective, simultaneous prevention of all 5 NC the predicted reduction in end-of-life dementia occurrence would reach only about 60%. It is clear that a very substantial proportion of ADRD cases in these cohorts are unexplained by any of the disease processes identified by virtue of these five NC.

DISCUSSION

The results reported here are based on more than two decades of rigorously standardized clinical and neuropathologic observations in three premier longitudinal cohort studies and abundantly supported by reports from other population-based studies. Each individual brain’s total neuropathologic burden was the dominant determinant of cognitive impairment. Constellations of two, three, or more different types of NC distributed across neural systems comprised that burden. Moreover, it is clear that these five dementing diseases failed to explain a sizable proportion of ADRD cases.

Employing these data we speculate that a future intervention that would fully prevent or ablate all Alzheimer NC might be expected to lower the occurrence of end-of-life severe cognitive impairment from about 37% (approximating today’s level) to 20-30%. A future intervention that would fully block development of all 5 of these common aging-related NC might reduce the prevalence of end-of-life impairment to about 15%, assuming no substantial change in longevity. These inferences suggest that a future prevention of ADRD may require a better understanding of brain aging and the multiple complex pathogeneses of cognitive decline than now exists.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (UF1 AG057707, UF1 AG053983, R01 AG021055, P50 AG016573). The funding sources did not provide scientific input for the study. We sincerely thank our research participants and their families for their participation in these studies. In addition, we appreciate the generous assistance and advice of Dr. Lenore Launer, who serves as guardian of the HAAS data archived at the National Institute on Aging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Neurology. 1984. Jul;34(7):939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pathological markers associated with normal aging and dementia in the elderly. Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Sliwinski MJ, Lipton RB, Grober E, Marks-Nelson H, Antis P. Ann Neurol. 1993. Oct;34(4):566–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hippocampal sclerosis: a common pathological feature of dementia in very old (> or = 80 years of age) humans. Dickson DW, Davies P, Bevona C, Van Hoeven KH, Factor SM, Grober E, Aronson MK, Crystal HA. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;88(3):212–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, et al. Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Nov 2002;977:9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montine TJ, Sonnen JA, Montine KS, Crane PK, Larson EB. Adult Changes in Thought study: dementia is an individually varying convergent syndrome with prevalent clinically silent diseases that may be modified by some commonly used therapeutics. Curr Alzheimer Res. Jul 2012;9(6):718–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. Jan 2012;123(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. Jan 2012;8(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zarow C, Weiner MW, Ellis WG, Chui HC. Prevalence, laterality, and comorbidity of hippocampal sclerosis in an autopsy sample. Brain Behav. Jul 2012;2(4):435–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cholerton B, Larson EB, Baker LD, et al. Neuropathologic correlates of cognition in a population-based sample. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36(4):699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corrada MM, Sonnen JA, Kim RC, Kawas CH. Microinfarcts are common and strongly related to dementia in the oldest-old: The 90+ study. Alzheimers Dement. Aug 2016;12(8):900–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenowitz WD, Keene CD, Hawes SE, et al. Alzheimer's disease neuropathologic change, Lewy body disease, and vascular brain injury in clinic- and community-based samples. Neurobiol Aging. May 2017;53:83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suemoto CK, Ferretti-Rebustini RE, Rodriguez RD, et al. Neuropathological diagnoses and clinical correlates in older adults in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. Mar 2017;14(3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Person-specific contribution of neuropathologies to cognitive loss in old age. Ann Neurol. Jan 2018;83(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flanagan ME, Cholerton B, Latimer CS, et al. TDP-43 Neuropathologic Associations in the Nun Study and the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(4):1549–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen MT, Mattek N, Woltjer R, et al. Pathologies Underlying Longitudinal Cognitive Decline in the Oldest Old. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. Oct-Dec 2018;32(4):265–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Power MC, Mormino E, Soldan A, et al. Combined neuropathological pathways account for age-related risk of dementia. Ann Neurol. Jul 2018;84(1):10–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson PT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): consensus working group report. Brain. Jun 1 2019;142(6):1503–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyle PA, Wang T, Yu L, et al. To what degree is late life cognitive decline driven by age-related neuropathologies? Brain. Aug 17 2021;144(7):2166–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodworth DC, Sheikh-Bahaei N, Scambray KA, et al. Dementia is associated with medial temporal atrophy even after accounting for neuropathologies. Brain Commun. 2022;4(2):fcac052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawas CH, Kim RC, Sonnen JA, Bullain SS, Trieu T, Corrada MM. Multiple pathologies are common and related to dementia in the oldest-old: The 90+ Study. Neurology. Aug 11 2015;85(6):535–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White LR, Edland SD, Hemmy LS, et al. Neuropathologic comorbidity and cognitive impairment in the Nun and Honolulu-Asia Aging Studies. Neurology. Mar 15 2016;86(11):1000–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyle PA, Yu L, Leurgans SE, et al. Attributable risk of Alzheimer's dementia attributed to age-related neuropathologies. Ann Neurol. Jan 2019;85(1):114–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JL, Richardson H, Xie SX, et al. The development and convergence of co-pathologies in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. Apr 12 2021;144(3):953–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spina S, La Joie R, Petersen C, et al. Comorbid neuropathological diagnoses in early versus late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Brain. Aug 17 2021;144(7):2186–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montine TJ, Corrada MM, Kawas C, et al. Association of Cognition and Dementia With Neuropathologic Changes of Alzheimer Disease and Other Conditions in the Oldest-Old. Neurology. Jun 15 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelber RP, Launer LJ, White LR. The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study: epidemiologic and neuropathologic research on cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. Jul 2012;9(6):664–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. Spring; 1994;6(1):45–58; discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brookmeyer R, Kawas CH, Abdallah N, Paganini-Hill A, Kim RC, Corrada MM. Impact of interventions to reduce Alzheimer's disease pathology on the prevalence of dementia in the oldest-old. Alzheimers Dement. Mar 2016;12(3):225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latimer CS, Keene CD, Flanagan ME, et al. Resistance to Alzheimer Disease Neuropathologic Changes and Apparent Cognitive Resilience in the Nun and Honolulu-Asia Aging Studies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. Jun 1 2017;76(6):458–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montine TJ, Cholerton BA, Corrada MM, et al. Concepts for brain aging: resistance, resilience, reserve, and compensation. Alzheimers Res Ther. Mar 11019;11(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Launer LJ, Hughes T, Yu B, et al. Lowering midlife levels of systolic blopressure as a public health strategy to reduce late-life dementia: perspective from the Honolulu Heart Program/Honolulu Asia Aging Study. Hypertension. Jun 2010;55(6):1352–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, et al. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. Feb 12 2019;321(6):553–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.