Abstract

Background:

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a digestive system disorder. Patients with IBS have a significantly lower quality of life (QoL). In this study, we aimed to assess how IBS affects the Saudi Arabian population’s health-related (HR)-QoL.

Methods:

A cross-sectional Web-based survey was conducted with a representative sample (n = 1346) of patients who met the Rome IV criteria for IBS from all regions of the country between February and May 2021. The questionnaire surveyed participants’ socio-demographic data (nationality, sex, age, region, marital status, level of education, and occupation) and included 24 questions on IBS divided into four categories: (1) diagnosis; (2) symptoms; (3) impact on patients’ lives; and (4) management methods. The HR-QoL score was calculated using a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating worse QoL.

Results:

Most patients (83.3%) were diagnosed by a physician, and 66.7% had a family member or a friend with IBS. Mixed IBS was the most common type of IBS (26.4%). Factors associated with poor QoL and significantly associated with IBS included female sex, initial diagnosis by a general physician, intermittent symptoms, and being asymptomatic for weeks to months.

Conclusions:

Greater attention to the QoL of patients with IBS is required to help them deal with IBS and create supportive environments to reduce its psychological effects.

Keywords: Abdominal discomfort, gastrointestinal symptoms, health-related quality of life, irritable bowel syndrome, quality of life, survey

INTRODUCTION

Although many chronic diseases can cause lifelong impairment, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can significantly impact an individuals’ quality of life (QoL).[1] IBS is a disorder of the digestive system function characterized by recurrent abdominal pain accompanied by a change in bowel habits (constipation, diarrhea, or a combination of both).[2] There are various risk factors for IBS such as stress, family history of IBS, and genetic, environmental, and psychological factors.[3,4,5] Approximately 9%–23% of the world’s population suffer from IBS,[6] and one of five individuals may experience IBS at some point.[7] Around 13% of those visiting primary healthcare clinics seek treatment for IBS symptoms, and they are also the main patient population in gastrointestinal clinics.[8]

Rome IV defined IBS as a recurrent abdominal pain associated with two or more of the following criteria: related to defecation, associated with a change in the frequency of stool, and associated with a change in the form (appearance) of stool.[9] Patients with IBS experience higher rates of absenteeism, avoidance of social situations, and feel compelled to remain close to the bathroom, in addition to irritability, depression, reduced confidence, or anxiety.[10] IBS prognosis varies depending on the severity of symptoms, and individuals with mild or intermittent symptoms may be less impacted in their daily life compared with individuals with severe or persistent symptoms, while individuals with IBS who are asymptomatic may not experience these negative impacts and can have a better QoL.[11] Furthermore, IBS is divided into three categories according to the main clinical symptoms: diarrhea (IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), and mixed (constipation/diarrhea) (IBS-M).[12,13] Individuals with IBS have a significantly worse QoL,[14,15] almost two-fold lower, than that observed in patients with severe chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, and diabetes. In addition to significantly affecting QoL,[16,17] IBS also affects society (i.e., hours missed at work) and health services.[18] Therefore, assessing the impact of IBS on the QoL of Saudi patients with IBS is essential, as several studies have shown that the QoL of patients with IBS is lower than that of the general population. However, to our knowledge, no study has been conducted in Saudi Arabia to investigate how IBS influences the health-related (HR)-QoL of Saudi patients.

Thus, the objectives of this study were to (i) measure the prevalence of IBS in Saudi Arabia; (ii) assess the symptoms and methods for IBS management; (iii) assess levels of patient satisfaction regarding IBS remedies; and (iv) elucidate independent factors associated with poor QoL in patients with IBS.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional Web-based survey using a representative sample (n = 1346) of patients who met the Rome IV criteria for IBS, in all regions of Saudi Arabia. The study was conducted from February to May 2021.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all patients diagnosed with IBS based on a history of recurrent abdominal pain associated with defecation or a change in bowel habits, while the exclusion criteria were those who were not diagnosed with IBS, had other gastrointestinal problems, refused to participate in the study, and people who could not read.

Sampling and sample size

Following the annual statistics issued by the General Authority for Statistics in mid-2020, the sample size was calculated based on a standard deviation set at 1.96 for 95% confidence interval (CI), a margin of error of 4%, a response distribution of 50%, and the total population of Saudi Arabia within the age range of 18 to 70 years. Therefore, the minimum required sample size was calculated as 601. In this study, we almost tripled the sample size and received responses from 1848 participants. However, 502 responses were omitted due to incomplete initial results. Therefore, 1346 records were finally included in the analysis.

Development of the study questionnaire

The study questionnaire was developed after conducting an extensive literature review. The questionnaire was an Arabic-translated modified version and underwent preliminary testing before the actual data collection process began on a pilot sample. As a result, gaps were dealt with, and the questionnaire was modified accordingly.

The finalized questionnaire was used to survey the participants’ socio-demographic data (nationality, sex, age, region, marital status, level of education, and occupation) and included 24 questions divided into four categories: (1) questions related to IBS diagnosis; (2) questions related to IBS symptoms; (3) questions related to the impact of IBS on patients’ lives; and (4) questions related to methods used to manage IBS.

Data management and statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while numerical variables were presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR). We performed multiple-response analysis for distinct variables for which the participants might have selected multiple choices. The relevant items included the most vexing gastrointestinal symptoms, participants’ feelings when experiencing IBS symptoms, the number of treatments the participants had ever attempted, and the treatment used in the past three months. We used 13 items from the survey to calculate the HR-QoL score. The responses to these items were collected on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A raw score was calculated by adding the values for each participant (range: 13–65), and a percentage score was calculated to ease interpretation. The final percentage score ranged between 20 and 100; a higher score indicated worse QoL measures. We used a multivariate linear regression based on the backward stepwise method to investigate the factors associated with poorer QoL. All demographic and IBS-related characteristics were entered as independent variables, and the percentage QoL score was entered as the dependent variable. The results were expressed as beta coefficients and their respective 95% CIs. Results with a P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The analysis was conducted using RStudio (version 4.1.1).

Ethical considerations

The research proposal was approved by the Regional Research and Ethics Committee of King Abdulaziz University (Reference No. 444-21). The questionnaire contained a brief introduction explaining the objectives and benefits of the study. We obtained informed written consent from all participants. Data obscurity and discretion were maintained throughout the study.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Most respondents were of Saudi nationality (94.0%), female (73.0%), and 18–40 years old (77.1%). More than two-thirds of participants held a bachelor’s degree or higher (68.5%). Furthermore, more than half of the participants resided in the Western region (51.0%), were single (61.3%), and were students (51.4%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

| Parameter | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Saudi | 1,265 (94.0%) |

| Non-Saudi | 81 (6.0%) | |

| Sex | Male | 364 (27.0%) |

| Female | 982 (73.0%) | |

| Age | <18 | 69 (5.1%) |

| 18 to <40 | 1038 (77.1) | |

| 40 to <60 | 222 (16.5%) | |

| ≥60 | 17 (1.3%) | |

| Region | Western region | 690 (51.0%) |

| Eastern region | 182 (13.5%) | |

| Central region | 198 (14.7%) | |

| Northern region | 72 (5.3%) | |

| Southern region | 204 (15.2%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 825 (61.3%) |

| Married | 456 (33.9%) | |

| Divorced | 49 (3.6%) | |

| Widowed | 16 (1.2%) | |

| Occupation | Student | 692 (51.4%) |

| Not employed | 262 (19.5%) | |

| Employed—government | 265 (19.7%) | |

| Employed—private sector | 127 (9.4%) | |

| Educational level | Illiterate | 8 (0.6%) |

| Primary to secondary | 322 (23.9%) | |

| Diploma | 94 (7.0%) | |

| Bachelor’s or higher | 922 (68.5%) |

IBS characteristics

Most patients (83.3%) were diagnosed by a physician. Additionally, 66.7% had a family member or a friend with IBS. Of these, 23.3% of patients were diagnosed >5 years earlier, and 64.8% were first diagnosed by a gastroenterologist. Almost two-thirds of the sample (66.7%) had a family member with IBS. Mixed IBS was the most common type (26.4%), followed by IBS-C (21.4%) and IBS-D (13.3%). The most common frequency of physician visits was one to two times a year (37.4%), and laboratory testing was the most common method ordered by physicians (35.0%). The details of IBS characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of IBS

| Parameter | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Have you ever been diagnosed by a physician or other healthcare provider as having IBS? | Yes | 1,121 (83.3%) |

| When were you diagnosed with IBS? | <1 year | 244 (21.8%) |

| 1–2 years | 238 (21.2%) | |

| 2–3 years | 167 (14.9%) | |

| 3–4 years | 117 (10.4%) | |

| 4– 5 years | 94 (8.4%) | |

| >5 years | 261 (23.3%) | |

| Please indicate which healthcare provider first made your diagnosis | A gastrointestinal specialist | 726 (64.8%) |

| A family physician | 320 (28.5%) | |

| A general physician | 17 (1.5%) | |

| Others | 58 (5.2%) | |

| Do you have a family member or a friend with IBS? | Yes | 898 (66.7%) |

| Which type of IBS do you have? | IBS-M (mixed type) | 355 (26.4%) |

| IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant) | 179 (13.3%) | |

| IBS-C (constipation-predominant) | 288 (21.4%) | |

| Not sure | 524 (38.9%) | |

| How many times a year do you visit your healthcare provider? | 0 | 506 (37.6%) |

| 1–2 | 504 (37.4%) | |

| 3–5 | 239 (17.8%) | |

| 6–9 | 62 (4.6%) | |

| ≥10 | 35 (2.6%) | |

| When you went to your physician with the symptoms, the most common test ordered by your physician was: | Colonoscopy | 131 (9.8%) |

| Laboratory tests | 470 (35.0%) | |

| Gastroscopy | 81 (6.0%) | |

| Ultrasound | 108 (8.0%) | |

| Not sure | 507 (37.8%) | |

| Other | 46 (3.4%) | |

| Missing | 3 | |

| Can you predict your symptoms on a daily basis? | Not accurately at all | 146 (10.8%) |

| A little accurately | 289 (21.5%) | |

| Somewhat accurately | 672 (49.9%) | |

| Very accurately | 239 (17.8%) | |

| Do your GI symptoms come and go? | Yes No | 1,077 (80.0%) 271 (20.0%) |

| How long do you remain symptom-free before symptoms return? | A few hours | 237 (17.6%) |

| A few days | 462 (34.3%) | |

| A few weeks | 247 (18.4%) | |

| A few months | 191 (14.2%) |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal

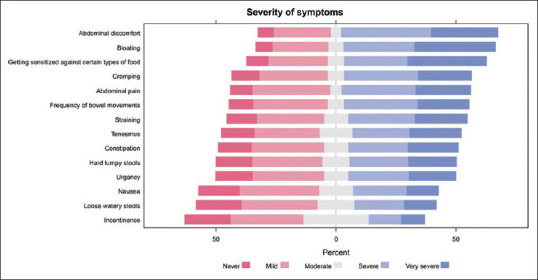

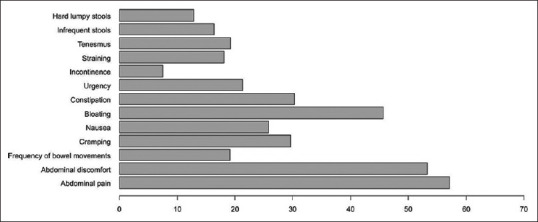

Severity of IBS symptoms

Most patients declared that the following symptoms were either mild or absent: loose, watery stool (50.5%), nausea (50.2%), and incontinence (49.3%). However, the most severe symptoms of IBS were (severe or very severe) abdominal discomfort (65.2%), bloating (63.4%), and sensitivity to certain types of food (59.2%) [Figure 1]. The most vexing symptoms were abdominal pain (57.1%), abdominal discomfort (53.3%), and bloating (45.7%) [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Severity of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms.

Figure 2.

IBS symptoms considered bothersome by patients. IBS, irritable bowel syndrome

HR-QoL and the associated factors

Less than half of the participants (42.4%) indicated that abdominal pain was mostly relieved after a bowel movement, while 72.7% stated that pain was relieved by moving or changing positions. In general, 38.1% of the participants had very or extremely bothersome gastrointestinal symptoms. Furthermore, 47.1% of patients reported that the symptoms interfered with their daily activities frequently or always. Incidentally, 25.0% of patients reported learning to live with these symptoms, while 20.4% and 19.8% were angry or depressed, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Association between IBS symptoms and daily activities

| Parameter | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| How often does the abdominal pain improve or stop after you have had a bowel movement? | Never or rarely | 104 (7.7%) |

| Sometimes | 671 (49.9%) | |

| Often | 385 (28.6%) | |

| Always | 186 (13.8%) | |

| How often is abdominal pain relieved by moving or changing positions? | Never or rarely | 284 (21.1%) |

| Sometimes | 695 (51.6%) | |

| Often | 274 (20.4%) | |

| Always | 93 (6.9%) | |

| Currently, how bothersome are your GI symptoms on your quality of life? | Not at all bothersome | 73 (5.4%) |

| A little bothersome | 285 (21.2%) | |

| Somewhat bothersome | 476 (35.4%) | |

| Very bothersome | 180 (13.4%) | |

| Extremely bothersome | 332 (24.7%) | |

| How often do your symptoms interfere with everyday life, such as work, school, and social situations? | Never | 60 (4.5%) |

| Rarely | 190 (14.1%) | |

| Sometimes | 462 (34.3%) | |

| Often | 401 (29.8%) | |

| Always | 233 (17.3%) | |

| When your GI symptoms are bothering you, how does that make you feel? | Frustrated | 142 (10.5%) |

| Embarrassed | 172 (12.8%) | |

| Angry | 275 (20.4%) | |

| Accepting | 336 (25.0%) | |

| Depressed | 267 (19.8%) | |

| Exhausted | 4 (0.3%) | |

| Lethargy | 2 (0.1%) | |

| Fear | 2 (0.1%) | |

| Pain | 3 (0.2%) |

IBS, inflammatory bowel disease; GI, gastrointestinal

The calculated HR-QoL score had a median (IQR) score of 60.0 (45.0, 73.8). To analyze the factors independently associated with a worse QoL (higher QoL score), we incorporated all demographic and IBS-related characteristics in a stepwise linear regression model [Table 4]. The results showed that worse QoL parameters were independently associated with residing in the Northern region (β = 6.66, 95% CI, 2.34 to 11.0, P = 0.003) and with being married (β = 3.12, 95% CI, 0.73 to 5.52, P = 0.011), divorced (β = 8.66, 95% CI, 3.37 to 13.9, P = 0.001), or widowed (β = 13.1, 95% CI, 3.49 to 22.7, P = 0.008). Furthermore, the frequency of visiting a healthcare provider was independently associated with worse QoL measures (1–2 visits per year: β = 2.76, 95% CI, 0.47 to 5.05, P = 0.018; 3–5 visits per year: β = 7.82, 95% CI, 4.96 to 10.7, P < 0.001; 6–9 visits per year: β = 9.92, 95% CI, 5.10 to 14.7, P < 0.001; and 10 or more visits per year: β = 10.3, 95% CI, 4.11 to 16.5, P = 0.001).

Table 4.

Results of linear regression analysis to assess the independent factors associated with worse quality of life scores

| Parameter | Category | Beta | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | — | — | |

| Female | -2.25 | -4.42, -0.08 | 0.042 | |

| Age | <18 | — | — | |

| 18 to<40 | 4.13 | -0.58, 8.84 | 0.085 | |

| 40 to<60 | 0.3 | -5.24, 5.85 | 0.915 | |

| ≥60 | -4.98 | -15.1, 5.13 | 0.334 | |

| Region | Western region | — | — | |

| Eastern region | -2.15 | -5.05, 0.74 | 0.145 | |

| Central region | 0.95 | -1.84, 3.75 | 0.503 | |

| Northern region | 6.66 | 2.34, 11.0 | 0.003 | |

| Southern region | 0.36 | -2.41, 3.14 | 0.798 | |

| Marital status | Single | — | — | |

| Married | 3.12 | 0.73, 5.52 | 0.011 | |

| Divorced | 8.66 | 3.37, 13.9 | 0.001 | |

| Widowed | 13.1 | 3.49, 22.7 | 0.008 | |

| Educational level | Illiterate | — | — | |

| Primary to secondary | -0.94 | -14.4, 12.5 | 0.891 | |

| Diploma | -2.2 | -15.9, 11.5 | 0.753 | |

| Bachelor’s or higher | -4.96 | -18.4, 8.46 | 0.469 | |

| Please indicate which healthcare provider first made your diagnosis | A gastrointestinal specialist | — | — | |

| A family physician | 0.81 | -1.32, 2.95 | 0.456 | |

| A general physician | -11.2 | -19.1, -3.17 | 0.006 | |

| Other | -0.32 | -4.44, 3.79 | 0.877 | |

| Which type of IBS do you have? | IBS-M (mixed type) | — | — | |

| IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant) | -0.4 | -3.57, 2.76 | 0.803 | |

| IBS-C (constipation-predominant) | 0.1 | -2.64, 2.84 | 0.944 | |

| Not sure | -3.86 | -6.31, -1.42 | 0.002 | |

| How many times a year do you visit your healthcare provider? | 0 | — | — | |

| 1–2 | 2.76 | 0.47, 5.05 | 0.018 | |

| 3–5 | 7.82 | 4.96, 10.7 | <0.001 | |

| 6–9 | 9.92 | 5.10, 14.7 | <0.001 | |

| ≥10 | 10.3 | 4.11, 16.5 | 0.001 | |

| When you went to your physician with the symptoms, the most common diagnostic test ordered by your physician was: | Colonoscopy | — | — | |

| Laboratory tests | 0.36 | -3.08, 3.81 | 0.835 | |

| Gastroscopy | 4.08 | -0.78, 8.94 | 0.100 | |

| Ultrasound | -1.77 | -6.27, 2.72 | 0.440 | |

| Not sure | -1.78 | -5.29, 1.74 | 0.321 | |

| Other | -5.5 | -11.6, 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| Do your GI symptoms come and go? | No | — | — | |

| Yes | -5.25 | -8.55, -1.94 | 0.002 | |

| How long do you remain symptom-free before symptoms return? | A few hours | — | — | |

| A few days | -1.72 | -4.48, 1.03 | 0.219 | |

| A few weeks | -4.25 | -7.40, -1.10 | 0.008 | |

| A few months | -9.67 | -13.1, -6.28 | <0.001 | |

| No answer | -8.27 | -12.4, -4.16 | <0.001 |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal; CI, confidence interval

In contrast, lower scores (better QoL) were independently associated with the female sex (β = -2.25, 95% CI, -4.42 to -0.08, P = 0.042), patients first diagnosed by a general physician (β = -11.2, 95% CI, -19.1 to -3.17, P = 0.006), and patients with intermittent symptoms (β = -5.25, 95% CI, -8.55 to -1.94, P = 0.002). Furthermore, compared to participants who were symptom-free for a few hours, participants who were asymptomatic for a few weeks (β = -4.25, 95% CI, -7.40 to -1.10, P = 0.008) and a few months (β = -9.67, 95% CI, -13.1 to -6.28, P < 0.001) had significantly lower scores [Table 4].

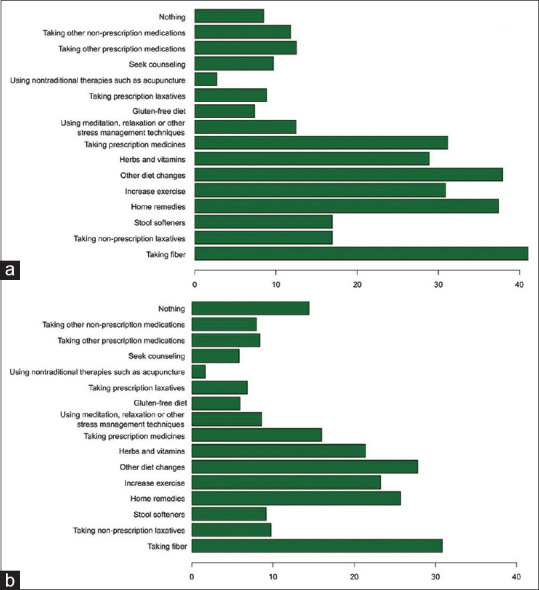

Treatment and satisfaction

When the participants were asked about the treatments that they have ever tried to manage IBS, we found that the most common managemental approaches included taking fiber (41.1%), making other diet changes (37.9%), and implementing home remedies (37.4%) [Figure 3a]. Similarly, fiber ingestion (30.8%), other diet changes (27.8%) and special home remedies (25.7%) were the most common approaches used in the past three months [Figure 3b]. Overall, the participants were satisfied (satisfied or extremely satisfied) with prescription remedies (34.2%), home remedies (34.1%), or increased physical exercise (33.6%). However, 66.0% of participants were unhappy with nontraditional therapies (e.g., acupuncture), and 61.8% and 60.0% were dissatisfied with a gluten-free diet or nonprescription medications, respectively [Table 5].

Figure 3.

Participants were asked about the treatments they used to manage IBS (a) overall and (b) in the past three months. Responses are shown in %. Common approaches included taking fiber (41.1%, 30.8%), other diet changes (37.9%, 27.8%), and home remedies (37.4%, 25.7%), respectively

Table 5.

Participants’ responses on their levels of satisfaction regarding IBS treatment

| Parameter | I did not take it | Not at all satisfied | Not satisfied | Neutral | Satisfied | Extremely satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking fiber | 312 (23.2) | 277 (20.6) | 324 (24.1) | 20 (1.5) | 76 (5.6) | 337 (25.0) |

| Taking nonprescription laxatives | 119 (8.8) | 419 (31.1) | 355 (26.4) | 47 (3.5) | 162 (12.0) | 244 (18.1) |

| Home remedies | 223 (16.6) | 219 (16.3) | 408 (30.3) | 37 (2.7) | 84 (6.2) | 375 (27.9) |

| Increase exercise | 308 (22.9) | 248 (18.4) | 317 (23.6) | 21 (1.6) | 73 (5.4) | 379 (28.2) |

| Other diet changes | 396 (29.4) | 186 (13.8) | 305 (22.7) | 24 (1.8) | 58 (4.3) | 377 (28.0) |

| Herbs, vitamins | 275 (20.4) | 278 (20.7) | 341 (25.3) | 23 (1.7) | 82 (6.1) | 347 (25.8) |

| Taking prescription medicines | 282 (21.0) | 255 (18.9) | 316 (23.5) | 32 (2.4) | 100 (7.4) | 361 (26.8) |

| Taking prescription laxatives | 142 (10.5) | 402 (29.9) | 372 (27.6) | 55 (4.1) | 137 (10.2) | 238 (17.7) |

| Using meditation, relaxation, or other stress management techniques | 202 (15.0) | 356 (26.4) | 390 (29.0) | 42 (3.1) | 103 (7.7) | 253 (18.8) |

| Gluten-free diet | 144 (10.7) | 449 (33.4) | 383 (28.5) | 33 (2.5) | 131 (9.7) | 206 (15.3) |

| Using nontraditional therapies such as acupuncture | 94 (7.0) | 515 (38.3) | 374 (27.8) | 50 (3.7) | 163 (12.1) | 150 (11.1) |

| Seeking counseling | 145 (10.8) | 357 (26.5) | 421 (31.3) | 56 (4.2) | 114 (8.5) | 253 (18.8) |

| Taking other prescription medications | 185 (13.7) | 385 (28.6) | 383 (28.5) | 41 (3.0) | 114 (8.5) | 238 (17.7) |

| Taking other nonprescription medications | 127 (9.4) | 431 (32.0) | 376 (27.9) | 58 (4.3) | 159 (11.8) | 195 (14.5) |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to estimate the prevalence of IBS and examine its impact on the QoL of patients with IBS across all regions of Saudi Arabia.

Most study participants were 18–40 years old, female, unmarried, lived in the Western region, and highly educated. Our results are consistent with those of a previous study conducted in Saudi Arabia in 2019, which showed that IBS was most common in individuals aged between 20 and 40 years.[19] Reports have indicated a higher IBS incidence in females than in males,[20,21,22,23] and genetic influence could play a role in IBS development in 30% of patients.[24,25]

Regarding IBS prevalence and the most common subtypes, Alharbi et al.[26] reported that IBS was more common among the residents of northern Saudi Arabia than in other regions. The most common subtype was IBS-M, followed by IBS-C, IBS-D, and IBS-U. Their results are inconsistent with our study’s results, which revealed that IBS was significantly associated with the population in western Saudi Arabia. The most common subtype was IBS-M, followed by IBS-C, and IBS-D.

We found that the most common IBS management approaches included fiber intake, other dietary changes, and the application of home remedies. This indicates that the Saudi Arabian population preferred behavioral changes and home remedies to visiting clinics. Therefore, the most common frequency of doctor visits was 1–2 times a year (37.4%); laboratory tests were the most common method ordered by physicians.

Our study indicated that the QoL of Saudi patients with IBS was affected by IBS and its symptoms, consistent with a study conducted in Japan, which revealed that patients with IBS reported a deterioration in their QoL and social activities due to the disease and its symptoms. These results are consistent with those of several studies conducted to date.[27,28,29]

Our findings revealed that IBS frequently or always interfered with daily activities in 47.1% of patients. These disturbing symptoms were accepted by 25.0% of patients, while 20.4% and 19.8% of patients felt angry or depressed, respectively. This observation is consistent with those in Japanese and European studies, which revealed a significant impact of bowel diseases on QoL, as patients often took leave from work, experienced fear and tension at work due to their illness, had difficulty building intimate relationships, and had difficulty learning.[25,30]

Notably, our results showed that the worst QoL measures were independently associated with (1) residing in the Northern region; (2) being married, divorced, or widowed; and (3) >1–2 clinic visits per year. Conversely, lower scores (better QoL) were independently associated with (1) female sex, (2) patients first diagnosed by a general physician, (3) patients with intermittent symptoms, and (4) participants who remained asymptomatic for weeks or months.

Regarding patient satisfaction, 66.0% were unhappy with using nontraditional treatments (such as acupuncture), and 61.8% and 60.0% were unhappy with a gluten-free diet and nonprescription medications. Again, this emphasizes the importance of educating patients about IBS, available and appropriate options for managing IBS, their pros and cons, and patients’ involvement in the management process.

Based on these results, we infer that more studies should evaluate the impact of demographic and social factors on the QoL of patients with IBS and identify potential predictive factors that affect the high and low QoL.

This study has some limitations. First, the survey relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to recall or social desirability bias. Second, although the sample was representative of patients who met Rome IV criteria for IBS in Saudi Arabia, it may not be generalizable to other populations with different cultural backgrounds or healthcare systems. Third, this study only provides a snapshot view at one point in time and does not track changes over time, which is considered a lack of longitudinal follow-up. Fourth, the absence of a control group makes it difficult to determine whether factors associated with poor QoL are unique to IBS patients or common among all individuals experiencing similar symptoms.

Nevertheless, the study has many strengths, including the use of a cross-sectional Web-based survey on a representative sample of patients who met the Rome IV criteria for IBS from all regions of Saudi Arabia between February and May 2021. It also used a comprehensive questionnaire that surveyed participants’ socio-demographic data and included 24 questions on IBS, divided into four categories: diagnosis, symptoms, impact on patients’ lives, and management methods. Also, only a few studies in Saudi Arabia have addressed the impact of IBS on patient QoL. Thus, our study plugs a significant gap in scientific knowledge as it determined the association of demographic and social factors in IBS patients with high and low QoL. Moreover, it identifies the factors that negatively affect their QoL to help in implementing appropriate interventions. Common factors impacting these patients’ QoL are the severity of symptoms, comorbid anxiety, depression, negative beliefs about IBS, and poor coping strategies. A combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions can address these factors. This may include developing personalized symptom management plans with dietary modifications, medication, and lifestyle changes; recommending psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to reduce anxiety and depression and improve coping strategies; educating patients about IBS and providing resources and support groups to help them feel more empowered; and using mind–body therapies such as yoga and meditation to reduce stress and improve QoL. By taking a multidisciplinary approach, healthcare providers can help individuals with IBS manage their symptoms effectively and achieve better health outcomes.

In conclusion, our findings show that most patients experienced IBS-M, and gastrointestinal symptoms were very or highly vexing to 38.1% of participants. Furthermore, symptoms frequently or constantly interfered with daily activities for 47.1% of patients. However, 25.0% of patients tolerated these vexing symptoms, while 20.4% and 19.8% felt angry or depressed, respectively. These findings should prompt greater attention, especially from clinicians and health care educators, to help patients deal with IBS and develop supportive environments to reduce symptoms’ psychological and physical effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.What is IBS?National Health Service (United Kingdom) 2021. [[Last accessed on 2022 Jul 15]]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs/

- 2.Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1393–407. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah E, Rezaie A, Riddle M, Pimentel M. Psychological disorders in gastrointestinal disease: Epiphenomenon, cause or consequence? Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:224–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nojkov B, Rubenstein JH, Chey WD, Hoogerwerf WA. The impact of rotating shift work on the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in nurses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:842–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saha L. Irritable bowel syndrome:pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6759–73. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quigley E, Fried M, Gwee K, Olano C, Guarner F, Khalif I, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: A global perspective. Jupiterpharma.in. 2009. Available from: http://www.jupiterpharma.in/journalpdf/IBS%20WORLD%20GASTRO.pdf .

- 7.Soares RLS. Irritable bowel syndrome, food intolerance and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. A new clinical challenge. Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55:417–22. doi: 10.1590/S0004-2803.201800000-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–31. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med. 2017;6:99. doi: 10.3390/jcm6110099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou X, Chen S, Zhang Y, Sha W, Yu X, Elsawah H, et al. Quality of life in patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), assessed using the IBS-Quality of Life (IBS-QOL) measure after 4 and 8 weeks of treatment with mebeverine hydrochloride or pinaverium bromide: Results of an international prospective observational cohort study in Poland, Egypt, Mexico and China. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34:783–93. doi: 10.1007/s40261-014-0233-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drossman DA, Chang L, Bellamy N, Gallo-Torres HE, Lembo A, Mearin F, et al. Severity in irritable bowel syndrome: A Rome Foundation Working Team report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1749–59. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.201. quiz 1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1736–41. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bommelaer G, Poynard T, Le Pen C, Gaudin AF, Maurel F, Priol G, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and variability of diagnostic criteria. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:554–61. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(04)95011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li FX, Patten SB, Hilsden RJ, Sutherland LR. Irritable bowel syndrome and health-related quality of life: A population-based study in Calgary, Alberta. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:259–63. doi: 10.1155/2003/706891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Q, Verne GN. New insights into visceral hypersensitivity--clinical implications in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:349–55. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luscombe FA. Health-related quality of life and associated psychosocial factors in irritable bowel syndrome: A review. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:161–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1008970312068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60:77–81. doi: 10.1159/000007593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank L, Kleinman L, Rentz A, Ciesla G, Kim JJ, Zacker C. Health-related quality of life associated with irritable bowel syndrome: Comparison with other chronic diseases. Clin Ther. 2002;24:675–89. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson PR, Varney J, Malakar S, Muir JG. Food components and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1158–74. e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costanian C, Tamim H, Assaad S. Prevalence and factors associated with irritable bowel syndrome among university students in Lebanon: Findings from a cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3628–35. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chirila I, Petrariu FD, Ciortescu I, Mihai C, Drug VL. Diet and irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibrahim NK, Battarjee WF, Almehmadi SA. Prevalence and predictors of irritable bowel syndrome among medical students and interns in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah. Libyan J Med. 2013;8:21287. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v8i0.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butt AS, Salih M, Jafri W, Yakoob J, Wasay M, Hamid S. Irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric disorders in Pakistan: A case control study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:291452. doi: 10.1155/2012/291452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalantar JS, Locke GR, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Beighley CM, Talley NJ. Familial aggregation of irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective study. Gut. 2003;52:1703–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saito YA, Zimmerman JM, Harmsen WS, De Andrade M, Locke GR, 3rd, Petersen GM, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome aggregates strongly in families: A family-based case-control study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:790–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.1077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alharbi SH, Alateeq FA, Alshammari KI, Ahmed HG. IBS common features among Northern Saudi population according to Rome IV criteria. AIMS Med Sci. 2019;6:148–57. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueno F, Nakayama Y, Hagiwara E, Kurimoto S, Hibi T. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on Japanese patients'quality of life: Results of a patient questionnaire survey. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:555–67. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1241-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo E. Self-Care behavior and social support in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) J Japanese Soc Child Health Nurs. 2011;21:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito M, Togari T, Park MJ, Yamazaki Y. Difficulties at work experienced by patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and factors relevant to work motivation and depression. Jpn J Health Hum Ecol. 2008;74:290–310. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, Hommes D, Bell C, Avedano L. IBD and health-related quality of life -- discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]