Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The comparison of the educational curriculum improves the content and quality of the curriculum and needs to be revised and modified in line with the current needs of society. Development of nursing knowledge, the emergence of emerging diseases requires that the nursing curriculum be codified and provide the necessary skills to provide quality and safe care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The study aimed to Comparison of Iranian and Scandinavian Bachelor of Nursing Curriculum (Sweden). This descriptive–comparative study was conducted based on the Bereday model in four stages: Description, Interpretation, Juxtaposition, Comparison, and Analysis in 2022. We use relevant electronic databases such as PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Iran Medex, SID, Magiran, Google Scholar, Iran Doc, and Science Direct databases.

RESULTS:

The results showed that despite the similarities, the Swedish nursing curriculum had special features in most of the mentioned dimensions. Including decentralized admission, Fits the need, competency-based curriculum, attention to holistic care and intercultural care, use of new digital technologies in education, and clinical training and evaluation.

CONCLUSION:

It seems that the Iranian nursing curriculum is far from the mentioned perspective. Using the experiences of the world's top universities, such as Sweden, can improve the quality of nursing undergraduate programs and improve the nursing profession by eliminating current shortcomings.

Keywords: Baccalaureate, comparative study, curriculum, education, Iran, nursing, Sweden

Introduction

The existence of a comprehensive educational program is the main pillar of education in the training of human resources of the health system, and it is necessary that every educational program should be compiled, revised, or modified based on the needs of society[1] so that the changes made should lead to the flourishing of talents and the cultivation of the scientific spirit and creativity of students,[2] while the increasing demand for the quality and safe practice of nursing, the emergence of new educational technologies, the gap between theory and clinical practice, have caused the nursing curriculum of Iran, not responding to the changing needs of society.[3] The results of Noohi et al.'s[4] studies (2015) showed that Iran's undergraduate nursing curriculum compared to the nursing curriculum of the United States, Canada, Australia, Lebanon, England, Scotland, the UAE, and India had issues such as choosing goals, selecting students, research, and teaching methods. Evaluation of theory and practice needs serious revision and corrections. The results of other studies in this field show that despite the importance of curriculum in higher education, the design and formulation of nursing programs is not based on scientific support.[3] While the investigation of the evolution of the world's educational systems shows that most of the leading countries have benefited from comparative research in the field of education, so the comparative approach has become one of the standard and dynamic scientific methods that scientists and educational planners are interested, and it is mentioned as a necessary condition for designing new educational systems.[5,6] One of the most important standard methods for the comparative comparison of educational programs is the model of George Z. L. Brady 1969. This model has been used in various studies in Iran and other parts of the world to compare educational approaches.[3,4]

Therefore, this study was conducted with the aim of a comparative comparison of Iran's continuous undergraduate nursing education program with Scandinavian countries. Today, Scandinavian universities, especially Sweden, have the second-best higher education system in the world. So that in the latest scientific ranking of the world's top universities, many universities in these countries are not only very prominent in these countries, but also have a high ranking at the global level (QS). Six of the twenty universities rank among the world's top 100 in at least one ranking, and they are spread out across all four Scandinavian countries. Therefore, the results of this study by mentioning the reasons for the success and failure of Iran's nursing curriculum can be used to develop the nursing education system in Iran.[7]

Materials and Methods

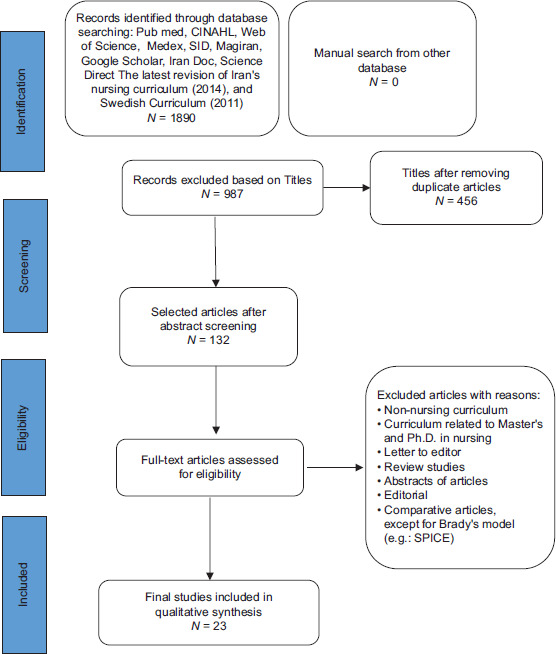

This scoping review study was conducted in 2022 based on the Bereday model at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. The Bereday model consists of four stages: description, interpretation, juxtaposition, and comparison. First, by comprehensively reviewing the history and educational status of Iran, Sweden, and Scandinavian countries, the nursing curriculums were studied. For this purpose, books and full-text articles in English and Persian were searched through a targeted search of library and electronic databases using the keywords: Nursing* OR “Nursing Students” OR Bachelor of Nursing AND Undergraduate Curriculum OR Undergraduate Program, AND, Iran OR Scandinavian Counties OR Nordic Countries OR Sweden AND Comparative Study and different combinations of the aforesaid words in the form of independent and their combination using Boolean operators in Pub med, CINAHL, Web of Science, Iran Medex, SID, Magiran, Google Scholar, Iran Doc, Science Direct databases. Non-nursing curriculum, curriculum related to Master's and Ph.D. in nursing, letter to the editor, review studies, abstracts, editorial, and comparative articles except for Brady's model (e.g. SPICE) were excluded. The last revision of the nursing curriculum was considered for the Iranian curriculum (2014) and for the Swedish curriculum (2011). Therefore, 23 related articles were selected from among 1890 studies [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Process of paper selection: Diagram flow PRISMA

Results

The results showed that despite the similarities, the Swedish nursing curriculum had special features in most of the mentioned dimensions including decentralized admission, Fits the need, competency-based curriculum, attention to holistic care and intercultural care, use of new digital technologies in education, and clinical training and evaluation. Comparison dimensions of nursing undergraduate curriculum between the two countries are listed in Tables 1-5.

Table 1.

Comparison of Iranian and Swedish Bachelor of Nursing Curriculum by definition, history, and evolution of nursing, philosophy, goals, perspective, and mission

|

Definition and history of nursing (Iran): Nursing is a branch of health sciences that provides health care based on knowledge and professional capabilities to provide maintain and promote health. Nursing in Iran started in 1916 and the four-year bachelor's of nursing degree program was approved In 1975.[8] Philosophy: based on the principle of human uniqueness. Vision: Over the next ten years, the Iranian undergraduate nursing curriculum, will be able to achieve regional and global standards of nursing education. Mission: Emphasis on the values of Islam and based on the needs of society.[8] Definition and history of nursing (Sweden): Nursing is a theoretical and clinical knowledge that interacts with subjects such as the humanities, care, natural sciences, social sciences, and the liberal arts. Vocational nursing education in the Scandinavian countries and Sweden has experienced three courses: A) Florence Nightingale (1920-1820). B) Academic era In the late 20th century. C) the Bologna Process.[9] Philosophy: Promoting health, using the capacity of individuals to solve problems, supporting patients as unique human beings, attention to the quality of education, democracy, rule of law, neutrality, Equality, gender diversity and critical perspective, and humor in education.[10] Vision: From 2017 to 2026, Swedish universities must be world-class and work to improve the world and the human condition.[11] Mission: Nursing education should be able to have all the expertise needed for advanced patient care and Teamwork to develop evidence-based performance, quality, and safety.[12] |

Table 2.

Comparison of curriculum structure and admission of undergraduate nursing students in Iran and Sweden

|

Structure of the curriculum & Student Admission (Iran): The 4-year curriculum has 22 public units, 54 private units, 15 basic sciences units, and 39 internship units. Each semester, several workshops are held according to the syllabus. After completing high school, passing the national exam in a centralized method, without interviews is done.[8] Structure of the curriculum & Student Admission (Sweden): The curriculum is three years and 180 Credits acquired full-time study/year and includes a minimum of 45 ECTS practical, a maximum of 135 ECTS theoretical, presented in two semesters and each semester is twenty weeks.[12] Completion of 10-12 years of secondary education and obtaining a diploma, pre-university, obtaining academic points in the entrance exam (66%), academic selection (34%) for non-native students, English B degree with a grade of 6, obtaining A score of 90 on the iBT test or a score of 575 on the PBT test, a minimum score of E in the Swedish language course, a high school diploma in mathematics at level 1a, 1b, 1c, as well as a certificate of a three-month Premedical internship.[12] |

Table 3.

Comparison of the content of Iranian and Swedish undergraduate nursing curricula by course

| Content of the Swedish Nursing Curriculum (ECTS) | Iranian Nursing Curriculum Content (Course) |

|---|---|

|

Nursing science: (180), Medical science:(135)* Theoretical (45), Clinical (15), Thesis (15) Foundation on Nursing practices and basic clinical studies (30): Profession and Nursing Science (18), Anatomy and Physiology (12) Basic Clinical Nursing Nursing in illness and diseases: (OB) (37) Pathophysiology, Mental health problems, Central concepts and theories, Care Plan, Pharmaceutical calculation Nursing in mental health (12) Nursing in primary care and in-home care (13.5) Scientific Theory and Method (4.5) Nursing in emergency care (15) Leadership, pedagogics, and management in nursing (7.5) Elective course (7.5) Nursing of the Elderly in a changing life situation (12) Interprofessional teamwork & Clinical Competence & leadership (15), Degree project (15).[13] |

Total: (130) theoretical units (91) Nursing Principles, Psychology, Biochemistry, Physiology, Anatomy, Microbiology, Parasitology, Quran, Safety and Traffic, Pharmacology & internship, Health assessment, Nursing concepts, Nutrition, Islamic thought, Physical education, General and Specialized English, Persian Literature, IT, Nursing ethics, Clinical Principles Internship, Maternal and child health & Internship, Medical-surgical nursing & internship, Epidemiology, Immunology, Ethics, Mental Health Nursing & internship, the process of client education, a Nursing internship in common problems, History of Islam, Health Nursing & Internship, Biostatistics, Research method, Pediatric Nursing, Nursing, and Environmental Health, Home Care Nursing & internship, Family and Population Knowledge, Sacred Defense, Intensive Care Nursing, Principles of Nursing Management, Emergency Nursing, Islamic Revolution, History of Islam, Intensive Care Nursing Internship.[8] |

The nursing skills are presented separately for each semester. *Full-time study always equals 30 ECTS credits per semester (20 weeks). OB: Obligatory, OP: Optional

Table 4.

Comparison of Iranian and Swedish nursing curricula by roles

|

Roles (Iran): Health and care, educational, research, counseling, management, support, and rehabilitation tasks.[8] Roles (Sweden): caring, Health, knowledge, and ability to work independently, self-awareness, establishing therapeutic relationships with patients and their families, communication, coordinating teamwork and supporting patients, clinical education, and application of theory in the clinic. Expected competencies: Theoretical-analytical competence, systematization Practical competence, learning & social competence in creating and maintaining interpersonal relationships and professional ethics.[9] |

Table 5.

Comparison of educational strategies, learner evaluation, accreditation of nursing curriculum

|

Educational Strategies, and evaluation (Iran): Task-based education, a combination of student and teacher-centered. It is based on formative and summative performance and the nursing board is responsible for external accreditation.[8] Educational Strategies, and evaluation (Sweden): Active learning, problem-based learning, process monitoring, and integrated learning with a focus on ideation are central to Swedish nursing programs.[14] Evaluation based on the ECTS system is done in formative and summative methods, but the greatest emphasis is on the self-evaluation of students and universities.[14] Pluralism & Deregulation in the evaluation of curriculum and related decisions are other features of Swedish nursing education that play an important role in the independence and epistemological foundation of the nursing profession.[15] |

Discussion

In this study, Iranian and Swedish undergraduate nursing curricula based on the Bereday model were reviewed and compared. Locally, Sweden is a member of the Nordic countries, a member of the European Union, and is strategically located in northern Europe.[16] The Swedish health system includes primary and secondary healthcare systems. General practitioners are usually the first point of contact, although people can consult specialists online or by phone about the need for a visit or hospitalization.[17] Iran is a country in Southwest Asia with an area of 1648195 square kilometers and consists of 30 provinces.[18] Sweden is one of the most immigrant-friendly countries, despite its smaller size and population than Iran, and its benefits such as high pensions, high living standards, justice, and educational equality.[19] However, tax increases and an aging population are among its problems.[20]

Comparison of Swedish and Iranian nursing curricula in terms of nursing definition, history, and evolution of nursing

Attention to natural sciences and free arts in the definition of nursing is one of the important points in the Swedish nursing curriculum, and the slogan of Swedish universities and nursing courses is to pay attention to natural sciences. The evolution of nursing education in both countries has been accompanied by ups and downs in the effort for the professional development of nursing. Although nursing education in Sweden started 80 years later than nursing in Iran, it seems to have made significant progress in nursing education. The presence of Swedish nursing theorists such as Katie Erickson, Kari Martinsen, and Karin Dahlberg has played a major role in the development of Swedish nursing and tradition has created a paradigm of ethics, ontology, and epistemology for the field of care science. These theories, while introducing the nursing profession as a science of care and the humanities, see care as a natural phenomenon in which, the health and suffering of the patient is a priority [Table 1].[21]

Comparison of Iranian and Swedish nursing curricula according to the conditions and admission of undergraduate nursing students

Decentralized admission with scientific and practical selection, fit to the needs of the community, passing nursing skills courses, the need to pay attention to English language skills, and high math, are the features of admission to a Swedish nursing student. However, the centralized admission system, high student admission, especially in free universities, regardless of the interest, motivation, and talent of students, is one of the problems for Iranian nursing student admission in this field. The findings of the present study were consistent with the results of Adib et al.[3] Of course, despite the increase in unemployment, the shortage of nurses in Iran is another important challenge. It seems that the lack of a nursing database, the inadequacy of statistical information provided between the Ministry of Health, the nursing system, and hospitals, as well as the admission of students without a proportional increase in job positions, are the cause of this discrepancy. At present, Iran has not even been able to reach the global standard of 3 nurses per 1000 people, while if it is to provide suitable services to the people, it is necessary to have 9 to 10 nurses per 1000 people; what Sweden has achieved [Table 2].[22]

Comparison of Iranian and Swedish nursing curricula in terms of philosophy, goals, perspective, and mission

Despite the similarities in the nursing curriculum philosophy of the two countries, which showed the importance of the profession, there are also differences. With the law of the Islamic Republic and Islamic beliefs, achieving the top-level needs of Maslow's hierarchy of needs is also reflected in this statement. But in the case of law and philosophy of nursing, it seems that the existence of courses such as Sociology, Philosophy, and Legal nursing is necessary. Nursing philosophy provides a perspective for performance, knowledge, and research and plays an important role in the production and development of the nursing profession.[23] To prevent and change the view of patient-centered care in the community, which is one of the goals of the Iranian curriculum, not only during education but also after graduation has not been operational. While providing community-based nursing services, is cost-effective. So that focusing on courses that are appropriate to society's needs, focusing on secondary prevention and treatment, lack of a community-based approach and health promotion, and excessive attention to specialization, are some of the problems of the Iranian nursing curriculum in this field, which is line with studies.[3,24] The main focus is on secondary prevention and treatment, lack of community-based approach,[24] excessive attention to specialization, lack of sociological attitude to the problems of the Iranian nursing curriculum in this area.[3] Comparing the curriculum philosophy, it seems that the curriculum perspective of the two countries is comprehensive, concise, and understandable and shows the future orientation of nursing education. However, more Swedish nursing than Iran has achieved its predetermined goals, to the extent that it is the second-best education in the world [Table 1].

In addition, in Swedish nursing education, patient-centered care, teamwork, evidence-based practice, research, and quality promotion and safety are crucial. But the mission, vision, and goals of the Iranian Nursing Bachelor's program emphasize identifying the needs of clients with a research perspective and care based on the nursing process, but it has not been achieved in reality the gap between education and clinic, the lack of obligation to implement the nursing process in the clinic, nursing shortage, can be considered as its causes, which is in accordance with the findings of Adib et al.[3] Swedish nursing education also has a unique focus on natural sciences, justice, and equality. The presence of units such as the impact of the environment on health and disease, and patient safety shows the importance of the issue so that Gutenberg University has selected this slogan; “Our Responsibility is Recognition Procedures, Equality, Environment, and Safety” [Table 1].

Comparison of the structure and educational content of the Iranian and Swedish nursing curriculum

The structure of the nursing curriculum of the two countries has public units, prerequisites, and basic and private units, but there are differences in the number and method of courses. While covering the goals of the Swedish Nursing Curriculum, its length of study is shorter than the Iranian Nursing Curriculum. In line with the definition of Swedish curriculum nursing, which is mainly described as focusing on the principle of care with an emphasis on social, behavioral, and human sciences, the courses are in line with this definition. Even, elective units including wound management (1, 2) and pharmaceutical calculations (1, 2, and 3) are directly related to the nursing profession. Öhlén et al.[10] (2011) showed that the Sweden universities chose curricula oriented toward Caring Science. The curricula based on Nursing Science provide an outline of the major subject's characteristics, content, and relationship to the profession. Courses such as pain management, on the other hand, are in line with the major subject as a professional discipline. A consequence of these differences is that the major subject in the Swedish nursing program lacks a common terminology and probably a common contextualization.[10] In the Iranian Nursing Curriculum, while the distribution of private units has problems, the existence of public units (such as literature and history) is completely unrelated to nursing. Public units can be developed in line with the goals of the nursing profession.

Another feature of Swedish education is the attention to e-health in nursing education. Sweden is one of the leading countries in digital technology and the second largest in the European Union in terms of the digital economy index.[17] The COVID-19 pandemic provided new insight into e-learning and the potential of this educational strategy for academia became apparent. Scandinavian countries such as Denmark, Finland, and Sweden are equipped with the latest technologies in the world and were most prepared for e-learning in the Corona crisis. In the Corona pandemic, Swedish nursing education, using new technologies such as audio podcasts, sound clouds, artificial intelligence, and the supportive role of professors, resulted in over 90% satisfaction among nursing students.[25] One of the challenges in the field of e-health in Iranian nursing is the existence of a working paper and the lack of university educational programs in this field. Especially today, due to the great emphasis on resource management, the cost-effectiveness of patient care, improving the quality of services, and tariffed nursing services, electronic nursing documentation record seems necessary. Iranian virtual nursing education is not sufficiently prepared in this field. Infrastructural problems, low bandwidth, low internet speed, limited capacity of expert human resources are the problems in this field. These findings are in accordance with the findings of Farsi, Safar, and Gharehbagh.[26,27,28] Crises such as re-emerging diseases and COVID-19 are always possible. The prevalence of Coronavirus can be an excuse to strengthen the infrastructure of virtual education to turn the current threatening situation into an opportunity and be a big step toward the development and maintenance of the quality of Iran's virtual nursing education system for the future. Because according to recent findings, disaster management is almost impossible without the use of new technologies.[29,30,31]

The last Swedish nursing curriculum, which was introduced in 2011, was based on Benner, focusing on pedagogy, and integrated education (subject, theory, and practice).[13] Critical thinking, ideation, nurse-patient communication skills, and patient support for active participation in the care process are the central units of Swedish nursing education. While the findings of studies in Iran showed that the lack of core competency in the nursing curriculum, incompatibility with educational goals, and evaluation process, are the problems in clinical nursing education.[3,32] As a result, biased approach training, routine-centered care, and lack of attention to students' creativity in the clinic have replaced evidence-based and patient-centered care, which is in line with other studies.[4,33] This is one of the reasons for the decrease in students' self-confidence for independent work in internships and has caused students to not have the necessary qualifications to provide evidence-based care.[34] Attention to intercultural care is another strength of the Swedish Nursing Curriculum. Lack of attention to this issue in the Iranian nursing curriculum has caused students and even nurses to be unaware of the care needs of patients with different cultures and experience care stress.[35] While Iran has a high capacity for health tourism, due to its geographical location, facilities, medical teams, low cost, and high quality of health services.[36] On the other hand, according to the ethical codes of the International Nurses Association, nursing care should be based on respect for the values of human beings regardless of nationality, language, religion, age, sex, values, cultural, and religious beliefs.[37] There is a need to pay more attention to the cultural diversity of clients in the Iranian Nursing Education.

In addition, in the Swedish nursing education system, caring science is the core the nursing system. The existence of a care plan course is separate from the nursing process and clinical skills. The existence of the Nursing Theories course focusing on care theories in the Swedish Bachelor of Nursing curriculum shows the importance of this issue. The main idea of care science in Sweden was introduced by Erickson.[9] Finnish theorists such as Laurie and Huntinen also developed systematic theory and Montinsen in Denmark and Norway, while describing nursing as an ethical profession, argued that nursing knowledge should be caring and nursing research should be done close to the clinical field and in a qualitative method.[21]

Comparison of Iranian and Swedish nursing curricula in terms of roles and capabilities

In terms of expected competencies, the Iranian nursing curriculum seems more accurate and complete than the Swedish curriculum, but in reality, there are huge differences. One of these discrepancies is in the research role of the graduates. So, Sweden's prestige is for leading research and innovative teaching methods.[10] Required 15 thesis units for all students with new and practical research topics show the importance of this. It is very important to be practical in nursing because it is part of the profession. Incapacity to achieve these tasks can adversely affect patient care.[38] Despite the research role in the Iranian nursing curriculum, this issue has not been considered and students are not drawn to research with the research methodology course. this finding is consistent with the results of Ahmadi et al.[39] The results of a systematic review in Iran showed that a lack of mastery of the research method is one of the most important barriers to practice based on nursing evidence.[40] But according to the findings of Widarsson et al. (2020), there is a smaller gap between theoretical and practical knowledge among newly graduated Swedish nursing students.[41] Other differences are the theoretical analytical and practical competence of Swedish nursing students. In other words, the ability to learn through observation, analysis, reflection, and problem-solving skills in the form of Systematization, the ability to acquire new knowledge and use it in new situations.[9] It can be said that Swedish nursing education has a holistic view of education that can be conducted without the presence of a teacher.[42]

Comparison of educational strategies, learner evaluation, nursing undergraduate curriculum

Sweden has three ministers of education for primary, secondary, and higher education. Using new teaching methods, creative thinking, developing intellectual skills, problem-solving, using simulators, emphasizing student self-assessment, and ideation are among the necessities of Swedish nursing education and have made it the second-best higher education in the world.[22] A high score is required to enter nursing, and most university programs are in Swedish and English. Nursing teachers use new educational methods in an intimate and informal setting without the need for rituals. The results of studies showed that Informal Learning Space (ILS) promotes comfort, flexibility, sensory stimulation, mutual trust, and respect, reduces stress, and increases students' confidence.[43]

In addition, Swedish nursing clinical education is student-centered and students should pursue patients and their identified care needs instead of following a clinical instructor. This approach increases preparedness for new situations and clinical decision-making. Reflection sessions are offered by qualified educators to increase analysis and self-reflection, and educators have only a supportive motivational role.[9] While the use of unqualified educators for clinical training, low inter-departmental relationships, and the lack of valid tools for assessment of some key competencies are challenges of clinical nursing education in Iran, that these findings are in line with other studies, which is in line with other studies [Table 5].

Commonly, comparison of the nursing curriculum of the two countries showed that despite the theoretical similarities, the Swedish nursing curriculum has specific differences in most of the noted dimensions. These can be referred to as the following: decentralized admission, short and competency-based curriculum, attention to holistic and intercultural care, training, and implementation of the nursing process and care plan, use of the latest digital technology strategies in education and evaluation, non-formal learning, Creativity, Student-Centered Self-Regulated Learning, attention to research, and their applicability. It seems that Iranian nursing is far from the noted philosophy. The increasing progress of science and the development of nursing knowledge, the complexity of care and cultural needs, and the emergence of emerging diseases need that the nursing curriculum is comprehensive, dynamic, and standard.

Conclusions

The application of comparative studies, including the present study, is to correct possible weaknesses and improve them to improve the quality of nursing education. Modeling the curriculum of successful countries in the world such as Sweden and comparing it improves the content, promotes and institutionalizes the efficient curriculum, and meets the dynamic needs of public health. The present comparative study is the only study that has described and interpreted the Swedish Nursing Curriculum. One of the limitations of the present study was this, considering that the undergraduate nursing curriculum in most of the Scandinavian countries (including Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Estonia) are very similar and only small differences in the master's and Ph.D. degree in nursing, and also due to the word count limits of the journal, the research team limited themselves to mentioning the Swedish nursing curriculum as the most prominent curriculum in this collection and refrained from mentioning duplicate content.

Financial support and sponsorship

This article is part of research approved with the financial support of the deputy of research and technology of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Health Information Technology department at the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, who provided great help in accessing the databases.

References

- 1.Hedayati A, Maleki H, Saadipour E.Contemplation on competency-based curriculum in medical education Iran J Med Educ 20161694–103 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khosid MR, Izadpanah AM.Factors affecting quality of education from the viewpoint of graduated nurses working in Birjand hospitals, 2012 Modern Care J 201411142–53 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adib HM, Mazhariazad F.Nursing Bachelor's Education program in Iran and UCLA: A comparative study J Military Sci 20196159–68 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noohi E, Ghorbani-Gharani L, Abbaszadeh A.A comparative study of the curriculum of undergraduate nursing education in Iran and selected renowned universities in the world Strides Dev Med Educ 201512450–71 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adick C.Bereday and Hilker: Origins of the ‘four steps of comparison’ model Comparative Educ 20185435–48 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell JJ.Comparative education in an age of competition and collaboration Comparative Education 2020. Jan 2;56(1):57–78 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Study.eu Team The 20 best universities in Scandinavia-2022 rankings. 2022. Available from: https://www.study.eu/article/the-20-best-universities-in-scandinavia-rankings. [Last accessed on 2022 Nov 29] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nabatchian F, Einollahi N, Abbasi S, Gharib M, Zarebavani M.Comparative study of laboratory sciences bachelor degree program in iran and several countries J Payavard Salamat, 201591–16 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Råholm MB, Hedegaard BL, Löfmark A, Slettebø A.Nursing education in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden–from bachelor's degree to PhD J Adv Nur 2010662126–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Öhlén J, Furåker C, Jakobsson E, Bergh I, Hermansson E.Impact of the Bologna process in Bachelor nursing programmes: The Swedish case Nurse Educ Today 201131122–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garmy P, Clausson EK, Janlöv AC, Einberg EL.A philosophical review of school nursing framed by the holistic nursing theory of Barbara Dossey J Holist Nurs 202139216–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goode D, Black P, Lynch J.Person-centred end-of-life curriculum design in adult pre-registration undergraduate nurse education: A three-year longitudinal evaluation study Nurse Educ Today 2019828–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theander K Wilde-Larsson B Carlsson M Florin J Gardulf A Johansson E, et al. Adjusting to future demands in healthcare: Curriculum changes and nursing students' self-reported professional competence Nurse Educ Today 201637178–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vierula J, Stolt M, Salminen L, Leino-Kilpi H, Tuomi J.Nursing education research in Finland—A review of doctoral dissertations Nurse Educ Today 201637145–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helgesson M, Marklund S, Gustafsson K, Aronsson G, Leineweber C. Favorable working conditions related to health behavior among nurses and care assistants in Sweden—A population-based cohort study. Front Public Health. 2021;9:801. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.681971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson WC.Western Europe 2020–2022. Rowman and Littlefield; 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glenngård A.The Swedish Health Care System. In: International Profiles of Health Care Systems. The Commonwealth Fund, p. 181–9, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/International_Profiles_of_Health_Care_Systems_Dec2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladier-Fouladi M.The Islamic Republic of Iran's New Population Policy and Recent Changes in Fertility Iranian Studies 2021. Dec;54(5-6):907–30 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane L, Wallengren-Lynch M, editors. Narratives of social work practice and education in Sweden. Springer Nature; 2020. Aug 3 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kruse A.Old age care: The Swedish way Soc Sci Spectr 2018365–71 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arman M, Ranheim A, Rydenlund K, Rytterström P, Rehnsfeldt A.The Nordic tradition of caring science: The works of three theorists Nurs Sci Q 201528288–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helakorpi J. Innocence, privilege and responsibility: Power relations in policies and practices on Roma, Travellers and basic education in three Nordic countries. Kasvatustieteellisiä julkaisuja. 2020 Aug 19; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butts JB, Rich KL.Philosophies and theories for advanced nursing practice Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2021. Aug 16 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riazi S, Dehghannayeri N, Hosseinikhah A, Aliasgari M.Understanding gaps and needs in the undergraduate nursing curriculum in Iran: A prelude to design a competency-based curriculum model Payesh (Health Monitor) 202019145–58 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laugesen K, Ludvigsson JF, Schmidt M, Gissler M, Valdimarsdottir UA, Lunde A, et al. Nordic health registry-based research: A review of health care systems and key registries. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:533. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S314959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farsi Z Sajadi SA Afaghi E Fournier A Aliyari S Ahmadi Y, et al. Explaining the experiences of nursing administrators, educators, and students about education process in the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study BMC Nurs 2021201–13. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00666-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safari Y. Mohtaram M. and Razi E., 2020. Explaining the Experience of Iranian Student Teachers on the Status of Virtual Education in the Corona Virus Pandemic: A Phenomenological Study International Journal of Schooling, 2(3), pp.17-32. Doi:10.22034/ijsc.2021.303934.1054 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gharehbagh ZA.A survey of professors' online teaching performance during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of nursing students of Islamic Azad University of Tehran Branch, Iran Med Educ Bull 2021269–77 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nejadshafiee M, Nekoei-Moghadam M, Bahaadinbeigy K, Khankeh H, Sheikhbardsiri H.Providing telenursing care for victims: A simulated study for introducing of possibility nursing interventions in disasters BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2022221–9. doi: 10.1186/s12911-022-01792-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaviani F, Aliakbari F, Sheikhbardsiri H, Arbon P.Nursing students' competency to attend disaster situations: A study in western Iran Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2021162044–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rezaei F, Maracy MR, Yarmohammadian MH, Sheikhbardsiri H.Hospitals preparedness using WHO guideline: A systematic review and meta-analysis Hong Kong J Emerg Med 201825211–22 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khazaee Z, Khazaee T, Ghannadkafi M, Zaher Ibrahimi M.The effect of using the obstetrics and gynecology logbook on the clinical skills of interns and trainees Strides Dev Med Educ 201310225–31 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shirazi F, Heidari S. The relationship between critical thinking skills and learning styles and academic achievement of nursing students. J Nurs Res. 2019;27:e38. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jasemi M, Whitehead B, Habibzadeh H, Zabihi RE, Rezaie SA.Challenges in the clinical education of the nursing profession in Iran: A qualitative study Nurse Educ Today 20186721–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Purabdollah M, Tabrizi FM, Khorami Markani A, Poornaki LS.Intercultural sensitivity, intercultural competence and their relationship with perceived stress among nurses: evidence from Iran Mental Health, Religion & Culture 2021. Aug 9;24(7):687–97 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zare Mehrjerdi Y, Sarv S, Akhavan A, Basouli M.Investigating the Factors Affecting the Development of Medical Tourism Using the System Dynamics Method and Evaluating Its Role in Economic Growth with the Benefit/Cost Index Journal of Tourism and Development 2022. Sep 23;11(3):39–59. DOI:10.22034/jtd.2020.239904.2084 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stievano A, Tschudin V.The ICN code of ethics for nurses: A time for revision Int Nurs Rev 201966154–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LoBiondo-Wood G, Haber J.Nursing Research E-Book: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidence-Based Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmadi Chenari H, Zakerimoghadam M, Baumann SL.Nursing in Iran: Issues and challenges Nurs Sci Q 202033264–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghojazadeh M, Azami-Aghdash S, Pournaghi Azar F, Fardid M, Mohseni M, Tahamtani T.A systematic review on barriers, facilities, knowledge and attitude toward evidence-based medicine in Iran J Res Clin Med 201431–11 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Widarsson M, Asp M, Letterstål A, Källestedt MS.Newly graduated Swedish nurses' inadequacy in developing professional competence J Contin Educ Nurs 20205165–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasalaei A, Amini M, Nabeiei P, Bazrafkan L, Mousavinezhad H. Barriers of critical thinking in medical students' curriculum from the viewpoint of medical education experts: A qualitative study. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2020;8:72. doi: 10.30476/jamp.2020.83053.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qazza N., 2021. A Framework for the Design of Informal Learning Spaces (ILS) to Facilitate Informal Learning in Jordan Universities (Doctoral dissertation, University of the West of England) [Google Scholar]