Abstract

PURPOSE

Blinatumomab, a bispecific T-cell engager immunotherapy, is efficacious in relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL (B-ALL) and has a favorable toxicity profile. One aim of the Children's Oncology Group AALL1331 study was to compare survival of patients with low-risk (LR) first relapse of B-ALL treated with chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy plus blinatumomab.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After block 1 reinduction, patients age 1-30 years with LR first relapse of B-ALL were randomly assigned to block 2/block 3/two continuation chemotherapy cycles/maintenance (arm C) or block 2/two cycles of continuation chemotherapy intercalated with three blinatumomab blocks/maintenance (arm D). Patients with CNS leukemia received 18 Gy cranial radiation during maintenance and intensified intrathecal chemotherapy. The primary and secondary end points were disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS).

RESULTS

The 4-year DFS/OS for the 255 LR patients accrued between December 2014 and September 2019 were 61.2% ± 5.0%/90.4% ± 3.0% for blinatumomab versus 49.5% ± 5.2%/79.6% ± 4.3% for chemotherapy (P = .089/P = .11). For bone marrow (BM) ± extramedullary (EM) (BM ± EM; n = 174) relapses, 4-year DFS/OS were 72.7% ± 5.8%/97.1% ± 2.1% for blinatumomab versus 53.7% ± 6.7%/84.8% ± 4.8% for chemotherapy (P = .015/P = .020). For isolated EM (IEM; n = 81) relapses, 4-year DFS/OS were 36.6% ± 8.2%/76.5% ± 7.5% for blinatumomab versus 38.8% ± 8.0%/68.8% ± 8.6% for chemotherapy (P = .62/P = .53). Blinatumomab was well tolerated and patients had low adverse event rates.

CONCLUSION

For children, adolescents, and young adults with B-ALL in LR first relapse, there was no statistically significant difference in DFS or OS between the blinatumomab and standard chemotherapy arms overall. However, blinatumomab significantly improved DFS and OS for the two thirds of patients with BM ± EM relapse, establishing a new standard of care for this population. By contrast, similar outcomes and poor DFS for both arms were observed in the one third of patients with IEM; new treatment approaches are needed for these patients (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02101853).

Blinatumomab plus chemotherapy is safe, and improves outcomes for low-risk relapsed ALL in the marrow.

INTRODUCTION

Despite improvements in survival for children with newly diagnosed ALL, approximately 10%-15% of patients relapse.1-3 Historical survival for children, adolescents, and young adults with first relapse of B-cell ALL (B-ALL) is poor with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of approximately 35%-50%.3-10 The most important predictors of outcome at first relapse are time from diagnosis, site of relapse, and minimal residual disease (MRD) remaining after 4 weeks of reinduction therapy.8-15 Patients experiencing bone marrow (BM) relapse with or without extramedullary (EM) (BM ± EM) disease ≥36 months or isolated EM (IEM) relapse ≥18 months from initial diagnosis, who have low (<0.1%) MRD at the end of reinduction chemotherapy, have historically been considered low risk (LR) due to more favorable outcomes. Standard treatment for LR patients is 2 years of chemotherapy, with radiotherapy for selected EM involvement, and without allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT).

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Does the addition of blinatumomab to standard chemotherapy improve outcomes for children, adolescents, and young adults with low-risk (LR) first relapse B-cell ALL (B-ALL) treated without allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplant?

Knowledge Generated

For children, adolescents, and young adults with LR B-ALL in first relapse, the addition of three cycles of blinatumomab to standard chemotherapy improved disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) for patients with a marrow relapse with or without extramedullary (EM) disease, but did not improve DFS/OS for patients with isolated EM relapse. Patients with isolated CNS relapse had poor DFS/OS with or without blinatumomab.

Relevance (C.F. Craddock)

-

Blinatumomab improves DFS and OS for children, adolescents, and young adults with LR first B-ALL bone marrow relapse with or without EM disease. Outcomes in LR patients with isolated CNS relapse remain poor with no evidence of benefit that blinatumomab improves outcome in this population for whom novel therapeutic modalities are required.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Charles F. Craddock, MD.

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager that links CD3+ T cells to CD19+ leukemia cells, inducing a cytotoxic immune response. Blinatumomab is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of adults and children with relapsed/refractory B-ALL,15,16 and received accelerated approval for MRD-positive B-ALL,17 conditional upon confirmatory trials. The Children's Oncology Group (COG) AALL1331 is one of the confirmatory trials to determine whether blinatumomab improved disease-free survival (DFS) and OS in children, adolescents, and young adults with first relapse of B-ALL. We reported previously that for high-risk and intermediate-risk (IR) patients, replacing two cycles of intensive chemotherapy with blinatumomab followed by HSCT significantly improved OS and reduced toxicities.18 Herein, we report the results for LR patients separately randomly assigned after reinduction to chemotherapy or chemotherapy with three 4-week blocks of blinatumomab.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Eligibility and Trial Oversight

Patients age 1-30 years with B-ALL first relapse were eligible. Marrow relapse was defined as >25% BM blasts (M3) after achieving remission. Isolated marrow (iBM) relapse was defined as M3 marrow without involvement of the CNS and/or testicles. CNS relapse was defined as positive cytomorphology and WBCs ≥5/µL or clinical signs of CNS leukemia (CNS3). Testicular leukemia was documented by biopsy if not associated with marrow relapse. IEM relapse included patients with CNS or testicular relapse with an M1 marrow (<5% blasts). Combined relapse included patients with ≥5% blasts in the marrow with CNS or testicular relapse. Patients with Down syndrome, Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, prior HSCT, or prior blinatumomab treatment were excluded. The AALL1331 Protocol (online only) and amendments were approved by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Pediatric Central Institutional Review Board (IRB) and by each center's IRB/Independent Ethics Committees. Written informed consent/assent were obtained before enrollment. The COG Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) independently reviewed trial safety and efficacy data.

Treatment and Risk Assignment

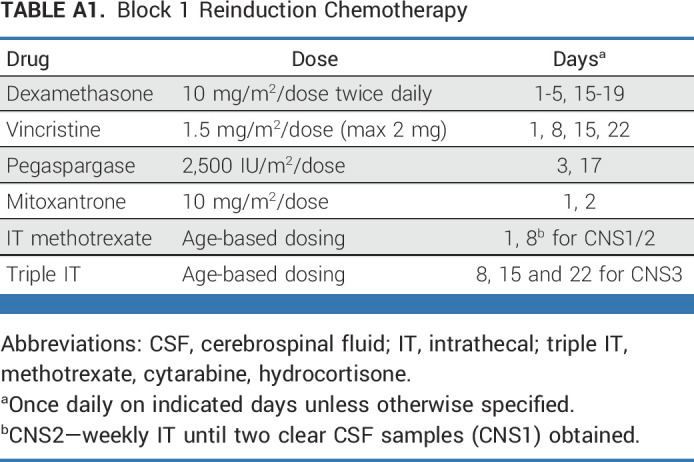

All patients received block 1 therapy (4 weeks) with vincristine, dexamethasone, pegaspargase, mitoxantrone, and risk-based intrathecal chemotherapy (Appendix Table A1, online only), similar to the previously published UKALLR3 clinical trial.8 Site of relapse was defined at enrollment. After block 1, BM was evaluated locally for morphologic response and centrally in a single reference laboratory for MRD by flow cytometry.19 MRD negativity was defined as <0.01%. Evaluations for EM disease included lumbar puncture for CNS leukemia and testicular examination with biopsy for equivocal examinations. End-induction risk groups were (1) early treatment failure (TF): >25% BM blasts or persistent CNS leukemia; (2) High-risk:BM (includes iBM and combined BM/EM) relapse <36 months after diagnosis, or IEM relapse <18 months after diagnosis; (3) IR:BM relapse ≥36 months after diagnosis, or IEM relapse ≥18 months after diagnosis; and MRD ≥ 0.1%; (4) LR: same as IR except MRD < 0.1%. In addition, patients with IEM ≥ 18 months after diagnosis with unknown MRD were considered negative and thus LR. MRD < 0.1% at end of reinduction was chosen to stratify IR versus LR, as patients with a first marrow relapse ≥36 months after diagnosis and MRD < 0.1% after reinduction have excellent survival with chemotherapy without transplant.20-22 Conversely, relapse ≥36 months after diagnosis and MRD ≥ 0.1% after reinduction is associated with poor survival of only 50%-60%.20,21

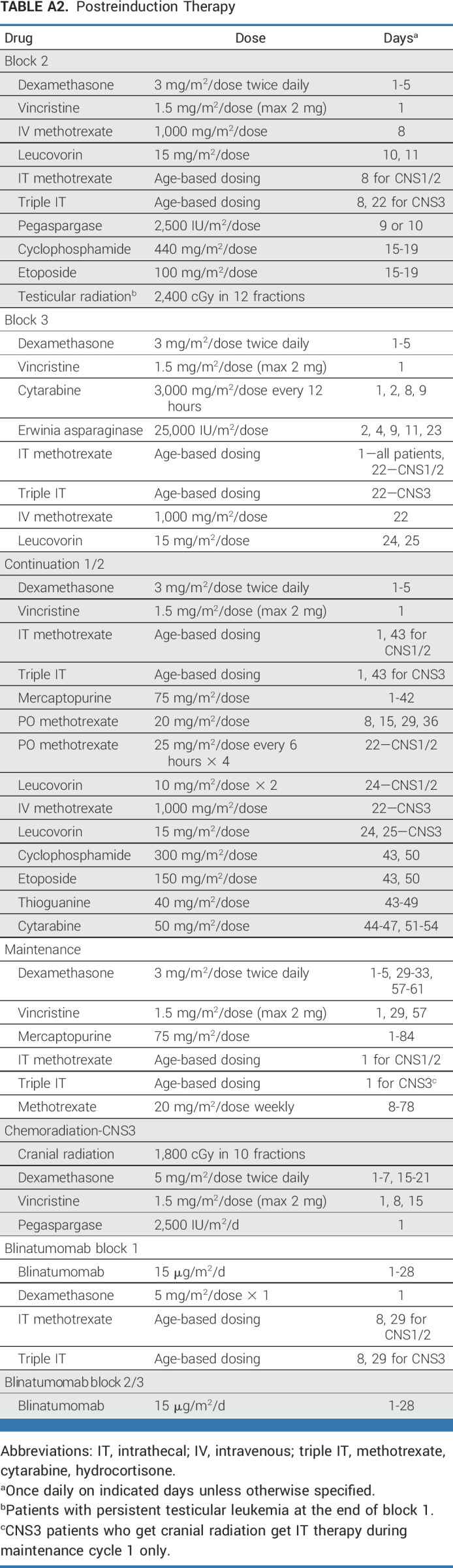

After block 1 reinduction, LR patients were randomly assigned to standard therapy including two intensive chemotherapy blocks followed by two continuation cycles and maintenance chemotherapy (arm C), or block 2 chemotherapy with 4 weeks of blinatumomab replacing block 3 followed by continuation chemotherapy intercalated with two 4-week blinatumomab blocks, followed by maintenance therapy (arm D; Fig 1). Several modifications to the UKALL R3 regimen were made for patients with CNS3 involvement: intrathecal triples (ITT; methotrexate [MTX], cytarabine, and hydrocortisone) replaced IT MTX. Two additional ITT doses were given during block 1 and one additional during block 2. Lower-dose oral MTX (25 mg/m2 once every 6 hours × four doses) was replaced with intermediate-dose intravenous MTX (1,000 mg/m2 once over 36 hours) during each continuation phase. Cranial radiotherapy (CRT) 18 Gy was administered later in AALL1331 after maintenance cycle 1 (week 40 for the control arm and week 54 for the experimental arm) compared with ALLR3 (week 14) to maximize delivery of early intensive MTX. Patients with testicular leukemia persisting after block 1 received testicular radiation during block 2. Patients received a total of 2 years of therapy from the start of block 1. Allogeneic HSCT was not included for either arm. To balance potential confounding factors, random assignment was stratified by site of relapse (BM ± EM v IEM) and end-block 1 MRD (<0.01% v 0.01%-0.1%).

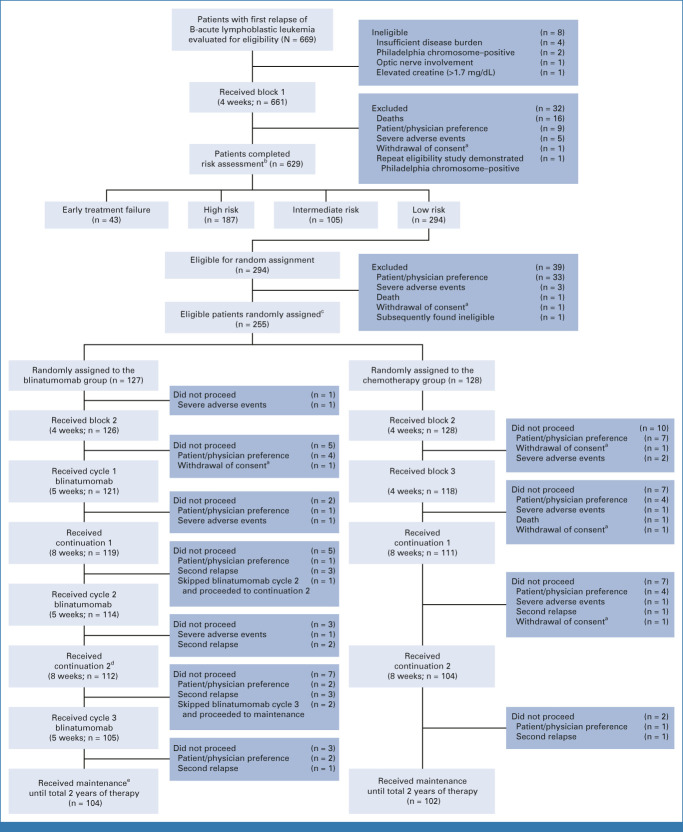

FIG 1.

CONSORT diagram. aPatients were censored at the time of withdrawal of consent in the analyses. bRisk group definitions: (1) early treatment failure: >25% marrow blasts or failure to clear CNS leukemia; (2) high risk: bone marrow relapse <36 months after diagnosis, or isolated extramedullary relapse <18 months from diagnosis; (3) intermediate risk: bone marrow relapse ≥36 months after diagnosis, or isolated extramedullary relapse ≥18 months after diagnosis; and MRD ≥ 0.1%; (4) low risk: same as intermediate risk, except MRD < 0.1%. c1:1 random assignment, stratified by risk group, site of relapse, first remission duration, and postreinduction MRD. dOne proceeded to continuation 2 after continuation 1. eOne proceeded to maintenance after blinatumomab cycle 1. One proceeded to maintenance after blinatumomab cycle 2. MRD, minimal residual disease.

During blinatumomab blocks, blinatumomab 15 μg/m2/d was given intravenously as a 28-day continuous infusion, followed by a 1-week rest period. Dexamethasone 5 mg/m2/dose was given once 30-60 minutes before starting blinatumomab or after an interruption of ≥4 hours in the first block. The chemotherapy blocks, including risk-adapted intrathecal chemotherapy, are described in Appendix Table A2 (online only).

Outcome and Statistical Analysis

The primary end point for the LR random assignment was DFS, defined as the time from random assignment to relapse, second malignancy, or death, whichever occurred first. The secondary end point was OS (time from random assignment to death from any cause). Adverse events (AEs) were graded with the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0, and AEs ≥ grade 3 were categorized as severe. Selected blinatumomab-related AEs were monitored including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity-related AEs.

The trial was designed to randomly assign 206 LR patients to have 80% power to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.55 with a one-sided log-rank test and type-I error of 0.05, corresponding to an increase in 3-year DFS from 73% (control) to 84% (experimental) with a 45% reduction in hazard rate. After faster-than-expected accrual of the LR arm, study accrual was extended, with a plan to randomly assign 236 subjects. The expected number of events was 80. With this sample size, the study had 85% power to detect an improvement with blinatumomab to 84% DFS with a one-sided alpha level of .05 with 118 patients per randomized group. Three planned analyses (two interim analyses and one final analysis) were performed when the observed number of events were 25, 47, and 84, respectively. Data were released by DSMC after final analysis. Efficacy stopping boundaries were based on the O'Brien-Fleming spending function.23,24 Futility boundaries were based on testing the alternative hypothesis at the 0.039 level.25

Here are data as of September 30, 2021. The analysis set was defined to include all patients randomly assigned per protocol. For DFS and OS analyses, patients with no events were censored at the time of last follow-up. AEs were assessed in the as-treated population (patients randomly assigned and receiving at least one dose of randomized therapy). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate DFS/OS, with standard errors assessed with the Greenwood method.26 One-sided stratified log-rank test was used to compare DFS/OS between randomized groups. HRs and associated 95% CIs were calculated using stratified Cox proportional-hazards models. The one-sided analyses were included in the original study design because of the burden of 28-day continuous infusions, as blinatumomab would only be adopted if the outcome was superior. Proportional hazards assumption was tested using graphical diagnostics and verified on the basis of scaled Schoenfeld residuals.27 Besides the planned comparison of DFS/OS between blinatumomab and chemotherapy among all randomly assigned LR patients, post hoc comparisons of DFS/OS were performed in two major subsets: patients with BM ± EM relapse and patients with IEM relapses, with type-I error controlled using the Bonferroni method.28 Other subset analyses were exploratory. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed with Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate, with a significance threshold of two-sided P = .05. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (College Station, TX).29

RESULTS

LR Random Assignment and Patients

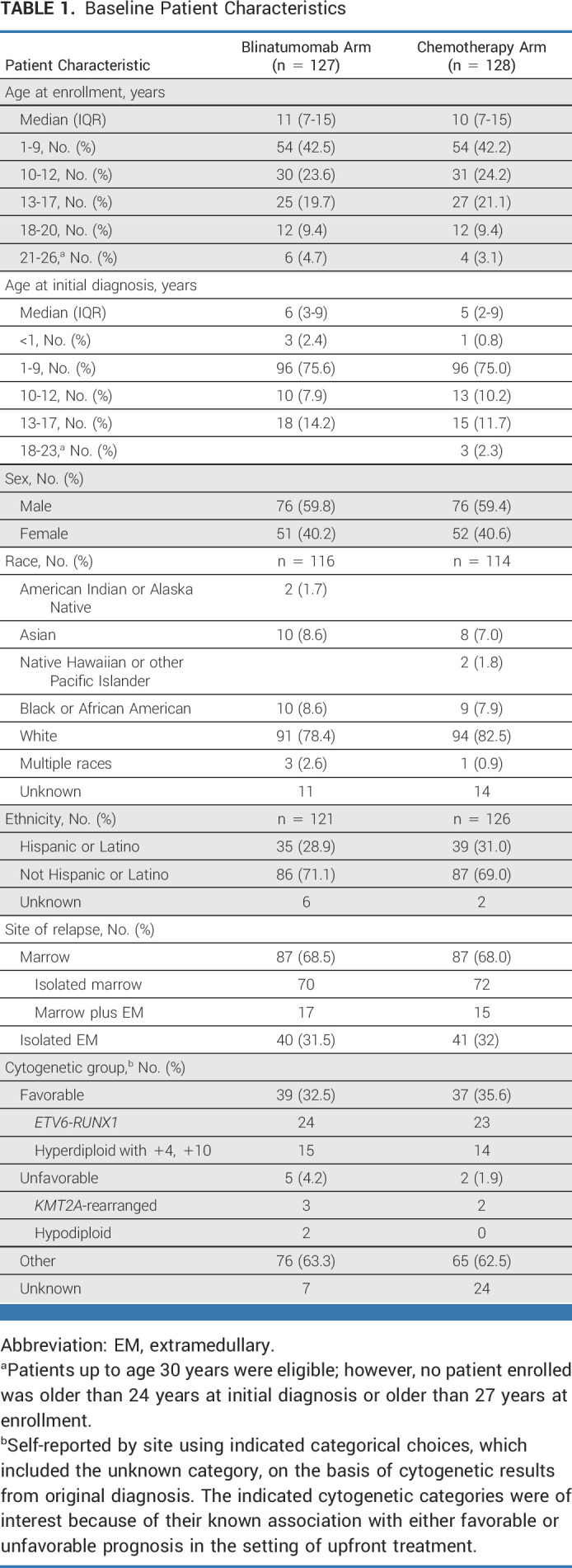

AALL1331 enrolled 669 patients between January 2014 and September 2019, with 661 eligible patients starting block 1 reinduction and 629 patients completing end-reinduction risk assignment (187 high-risk, 105 IR, 294 LR, and 43 TF). Of the 294 LR patients, 255 eligible patients consented to random assignment at end-reinduction and were randomly assigned: 128 arm C and 127 arm D. The groups were well balanced for clinically significant baseline characteristics (Table 1). Among 294 LR patients completing therapy, 121, 114, and 105 patients completed blinatumomab blocks 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Fig 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Outcomes of the LR Random Assignment

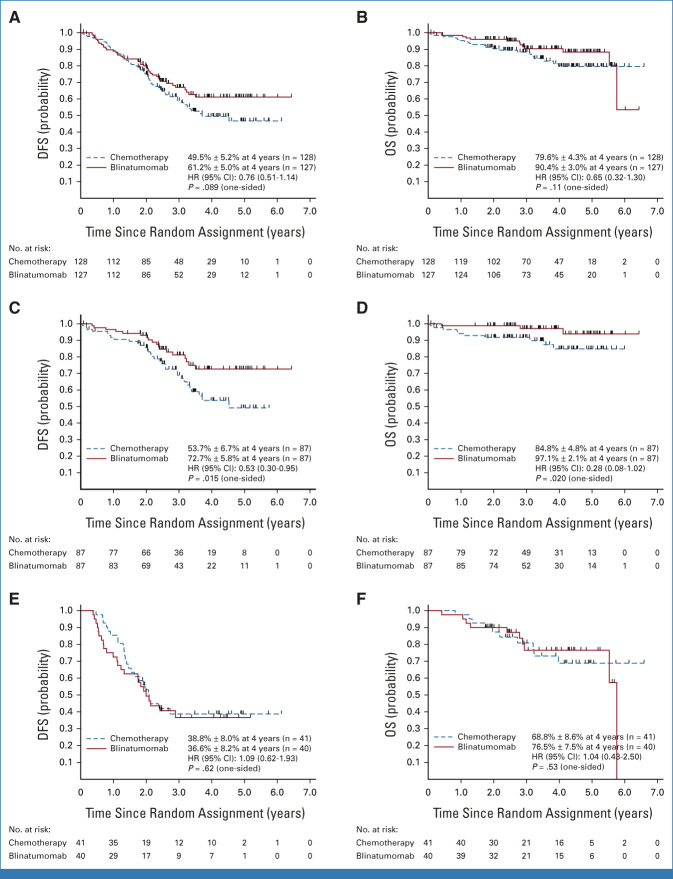

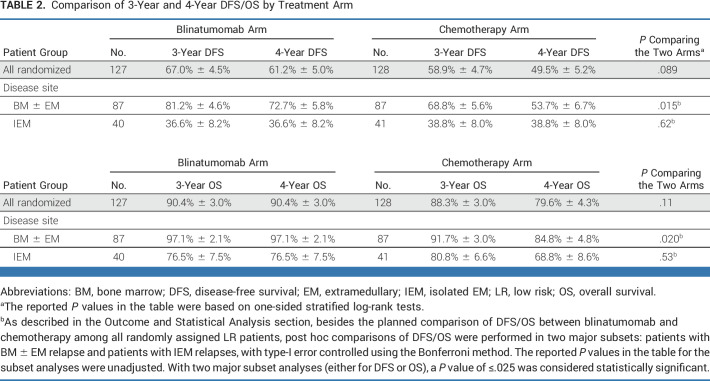

The median follow-up among living patients was 3.5 years (range, 25 days-6.6 years; IQR, 2.5-4.7 years). Among the 255 eligible randomly assigned LR patients, 97 DFS events occurred (42 blinatumomab and 55 chemotherapy), including 87 relapses, 1 second malignancy, and 9 deaths. The 4-year DFS rate was 55.2% ± 3.6%, and 4-year OS rate was 84.9% ± 2.7%. The 4-year DFS (P = .089) and OS (P = .11) rates were, respectively, 61.2% ± 5.0% and 90.4% ± 3.0% for blinatumomab versus 49.5% ± 5.2% and 79.6% ± 4.3% for chemotherapy (Figs 2A and 2B). Striking differences in DFS and blinatumomab efficacy were noted according to site of first relapse (Table 2). Analyses among patients with BM ± EM relapse demonstrated significant difference in DFS and OS between the two treatment arms after Bonferroni adjustment, but not in patients with IEM relapse.

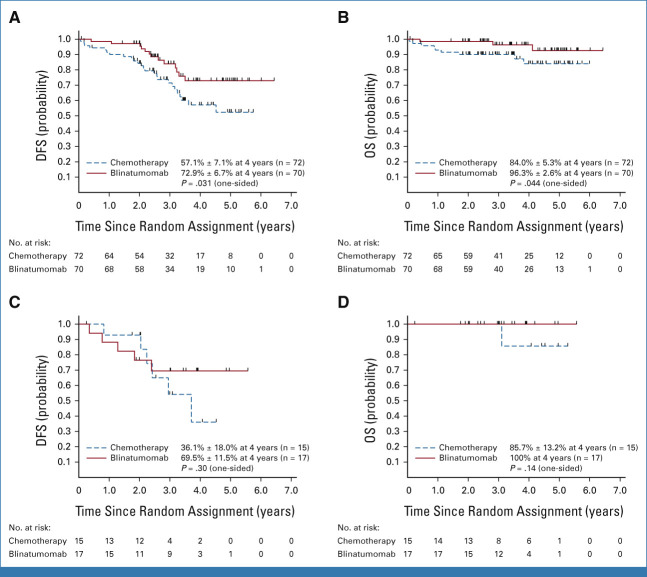

FIG 2.

(A) Disease-free survival and (B) overall survival of all LR patients. (C) Disease-free survival and (D) overall survival of LR patients with BM ± EM relapse. (E) Disease-free survival and (F) overall survival of LR patients with IEM relapse. P values were based on stratified log-rank tests, and HR and 95% CI were based on stratified Cox regression models. BM, bone marrow; DFS, disease-free survival; EM, extramedullary; HR, hazard ratio; IEM, isolated EM; LR, low risk; OS, overall survival.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of 3-Year and 4-Year DFS/OS by Treatment Arm

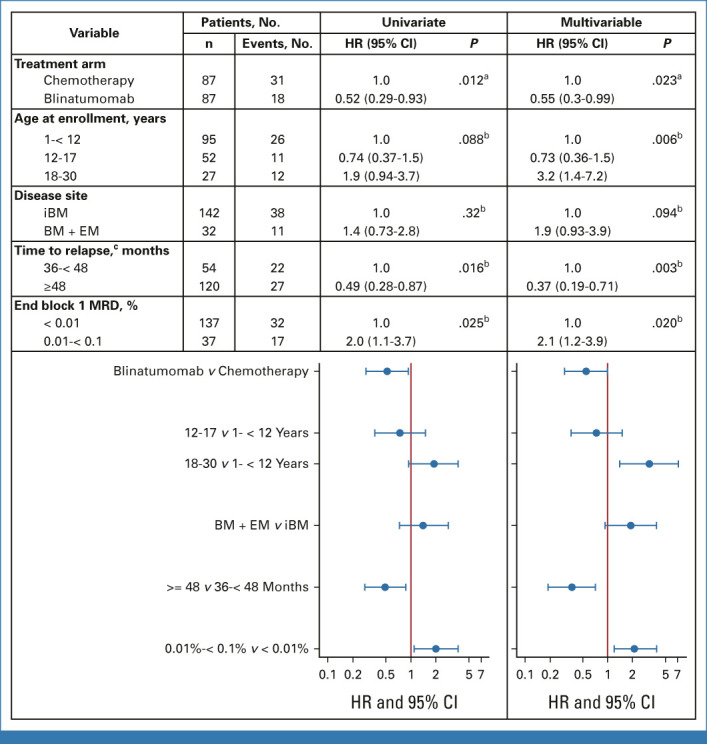

Approximately two thirds of patients (n = 174; 68.2% of randomly assigned patients) had a BM ± EM relapse at study entry. Of these, 49 had DFS events (18 blinatumomab/31 chemotherapy). The 4-year DFS (P = .015) and OS (P = .020) were, respectively, 72.7% ± 5.8% and 97.1% ± 2.1% for blinatumomab versus 53.7% ± 6.7% and 84.8% ± 4.8% for chemotherapy (Figs 2C and 2D). A Cox multivariable regression model evaluated associations between DFS with treatment arm, age at enrollment, relapse site, time from initial diagnosis to relapse, and end-block 1 MRD among BM ± EM relapses and showed the following significant associations with DFS: treatment arm (HR; 95% CI, 0.55; 0.30 to 0.99 for blinatumomab v chemotherapy), age at enrollment (HR; 95% CI, 3.2; 1.4 to 7.2 for patients age 18-30 v 1-12 years), time from diagnosis to relapse (HR; 95% CI, 0.37; 0.19 to 0.71 for relapse after 48 v 36-48 months), and end-block 1 MRD (HR; 95% CI, 2.1; 1.2 to 3.9 for MRD 0.01%-<0.1% v <0.01%; Fig 3).

FIG 3.

Cox regression of disease-free survival among patients with iBM or BM + EM disease. aP value for comparison of blinatumomab arm versus chemotherapy arm was one-sided. bP value for comparison of patient/disease characteristics was two-sided. cTime from initial diagnosis to relapse. BM, bone marrow; EM, extramedullary; HR, hazard ratio; iBM, isolated marrow; MRD, minimal residual disease.

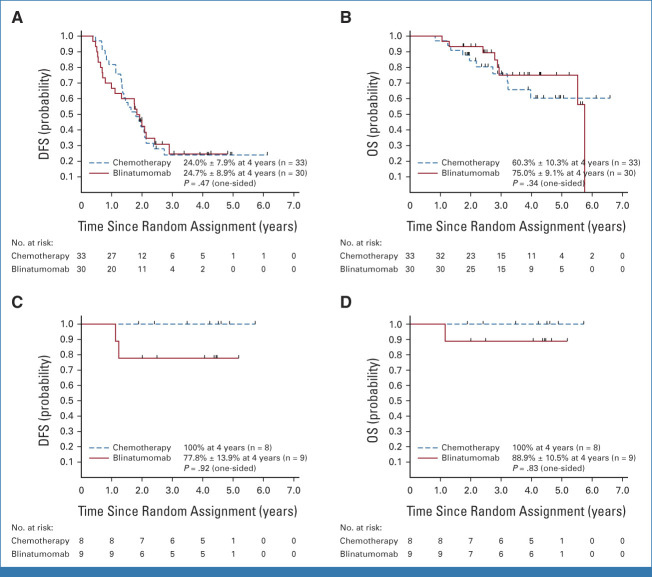

For iBM relapse (n = 142), the 4-year DFS (P = .031) and OS (P = .044), respectively, were 72.9% ± 6.7% and 96.3% ± 2.6% for blinatumomab versus 57.1% ± 7.1% and 84.0% ± 5.3% for chemotherapy. For BM + EM relapse (n = 32), the 4-year DFS (P = .30) and OS (P = .14), respectively, were 69.5% ± 11.5% and 100% for blinatumomab versus 36.1% ± 18.0% and 85.7% ± 13.2% for chemotherapy (Appendix Fig A1 [online only]).

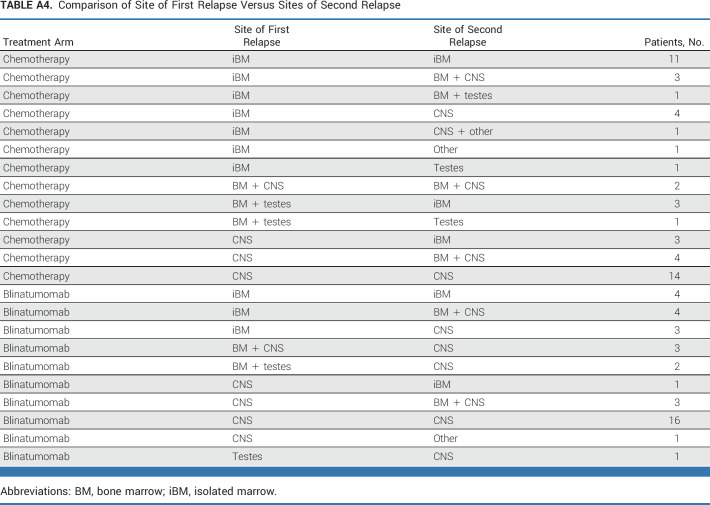

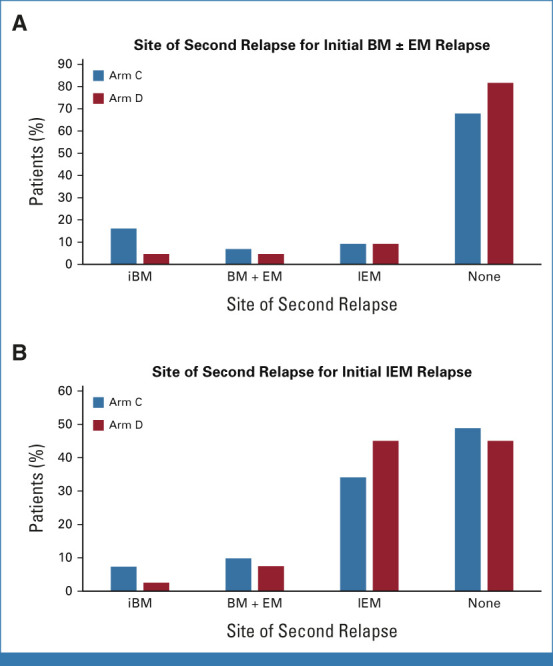

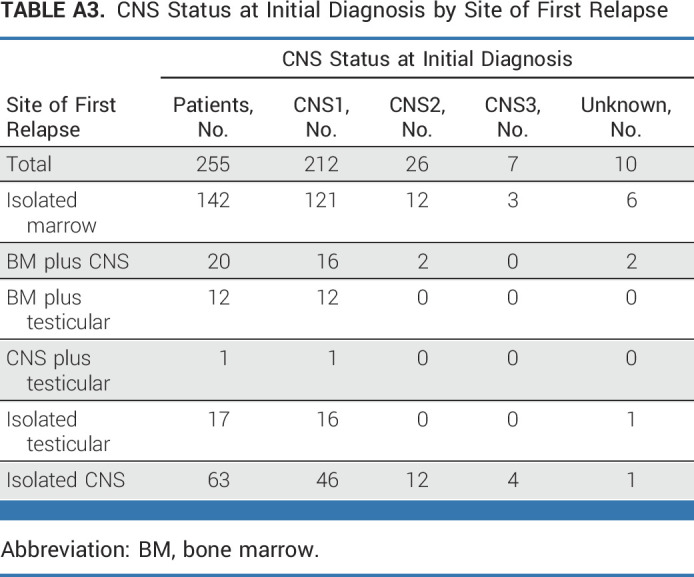

Approximately one third of patients (n = 81) had a late IEM relapse (25% CNS/6.7% testicular). The 4-year DFS (P = .62) and OS (P = .53) for these patients were, respectively, 36.6% ± 8.2% and 76.5% ± 7.5% for blinatumomab versus 38.8% ± 8.0% and 68.8% ± 8.6% for chemotherapy (Figs 2E and 2F). The only predictors of DFS in IEM patients was site of first relapse (HR for testes v CNS 0.19 [0.04-0.90]; P = .017) and time from diagnosis to first relapse (HR for >36 v 18-36 months 0.42 [0.20-0.91]; P = .017; Appendix Fig A2 [online only]). For isolated CNS (iCNS) relapses, 4-year DFS (P = .47) and OS (P = .34) were, respectively, 24.7% ± 8.9% and 75.0% ± 9.1% for blinatumomab versus 24.0% ± 7.9% and 60.3% ± 10.3% for chemotherapy. Among all randomly assigned patients, the median time from random assignment to CRT was 10 months (9-12) versus 12 months (11-15) in arm C/arm D, with two patients (arm C) and nine patients (arm D) relapsing before planned radiation. CNS status at initial diagnosis is shown in Appendix Table A3 (online only). For isolated testicular relapses, 4-year DFS (P = .92) and OS (P = .83) were, respectively, 77.8% ± 13.9% and 88.9% ± 10.5% for blinatumomab versus 100% and 100% for chemotherapy. The difference in DFS between BM ± EM and IEM patients was driven by second relapses in iCNS relapse patients (Fig 4, Appendix Table A4 [online only]). Of 63 iCNS relapse patients enrolled, 42 (66.7%) had a second relapse, of which 30 (71%) were also iCNS, with no difference by treatment arm. Of the 191 remaining patients whose relapse site did not involve the CNS, 45 (24%) had a second relapse (17 [18%] blinatumomab [eight BM ± EM, nine IEM], 28 [29%] chemotherapy [20 BM ± EM, eight IEM]). The 3-year OS after second relapse was 75.4% ± 8.4% for those patients originally randomly assigned to blinatumomab versus 60.5% ± 9.2% for chemotherapy (P = .13).

FIG 4.

Sites of first versus second relapses by treatment arm in patients with initial BM ± EM relapse (A) and patients with initial IEM relapse (B). BM, bone marrow; EM, extramedullary; iBM, isolated marrow; IEM, isolated EM.

Adverse Events

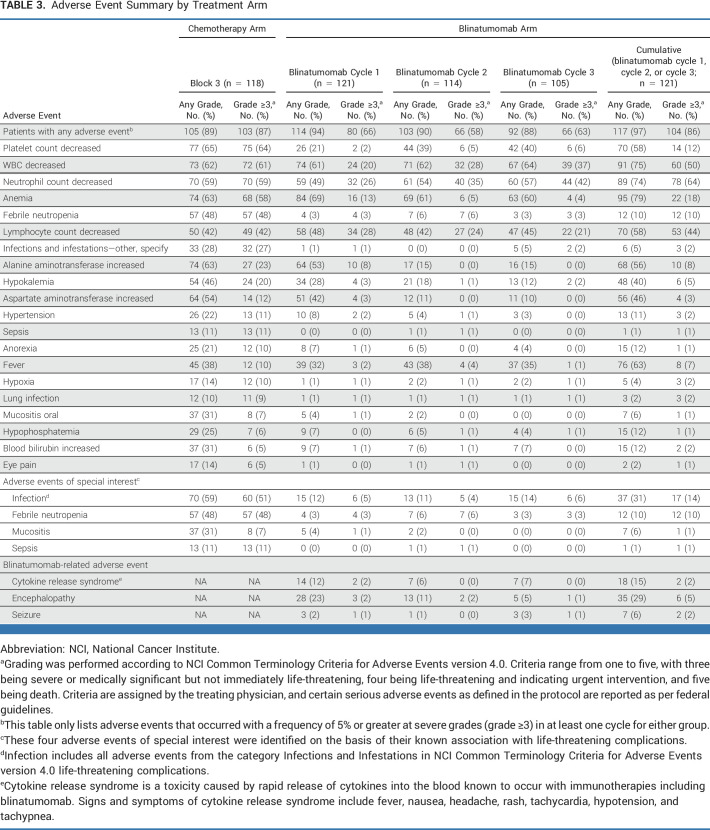

The first blinatumomab block was associated with significantly lower rates of severe toxicity (grade 3-5) than chemotherapy block 3, including febrile neutropenia (3% v 48%; P < .001), infections (5% v 51%; P < .001), sepsis (0% v 11%; P < .001), anemia (13% v 58%; P < .001), and mucositis (1% v 7%; P = .018). The rate of selected blinatumomab-related AE of all grades in blinatumomab cycles 1/2/3 were CRS 12%/6%/7%, seizure 2%/1%/3%; and other neurotoxicity/encephalopathy (cognitive disturbance, tremor, ataxia, dysarthria etc) 19%/9%/5%. The majority of other neurotoxicity/encephalopathy events was grade 1/2, with six patients (5%) having a grade 3-5 AE at any time. All blinatumomab-related AEs were fully reversible and only 2/127 randomly assigned (1.6%) patients could not proceed with therapy because of AEs (grade 3 tremor/seizure and grade 3 confusion/headache). The blinatumomab blocks did not result in treatment delays with a median of 35 days for each block of blinatumomab versus a median of 49 days in block 3 of chemotherapy. After random assignment, there were four grade 5 AEs (deaths), three in the chemotherapy arm (all infections-block 2, block 3, and maintenance) and one in the blinatumomab arm (adult respiratory distress syndrome-maintenance). AEs comparing treatment arms are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Adverse Event Summary by Treatment Arm

DISCUSSION

Among children, adolescents, and young adults with LR first relapse of B-ALL, treatment with blinatumomab did not result in a statistically significant difference in DFS/OS for the group as a whole. However, for the two thirds of patients with BM ± EM relapse, blinatumomab significantly improved DFS/OS when compared with standard chemotherapy. The 3-year DFS of 81.2% ± 4.6% and 4-year OS of 97.1% ± 2.1% are better than those reported in ALLR3,22 with similar DFS and superior OS compared with AALL0433 but with considerably less toxic therapy.21 The 3-year 58.9% DFS in the control arm was less than the predicted 73% because of the much lower-than-expected DFS among IEM patients with the 3-year 68.8% DFS for patients with BM ± EM similar to initial estimates. In all arms, OS is very good, suggesting that LR patients with second relapse are frequently salvaged.

The blinatumomab experimental arm was superior at preventing second relapse, and notably reduced the proportion of patients with a second marrow relapse. However, there was no difference between the two treatment arms in preventing second relapses in the CNS. In multivariable analysis of DFS for patients with BM ± EM relapse, age, time from initial diagnosis to relapse, and end-reinduction MRD were all predictive of outcome. Patients who were younger, relapsed later, and had undetectable MRD had superior outcomes.

Unfortunately, patients with IEM relapses did poorly with both arms, particularly those with iCNS relapse who had strikingly high second relapse rates with both arms leading to inferior DFS compared with previous studies.8,30,31 In this group, the majority of second relapses were in the CNS, again highlighting that blinatumomab was not effective in treating CNS disease. However, many of these patients remain alive after relapse, with 4-year OS rates of 68.8% ± 8.6% (chemotherapy) and 76.5% ± 7.5% (blinatumomab), but longer follow-up is needed to determine whether these patients have been cured after their second relapses and subsequent therapy.

The lower DFS rate for iCNS relapses in the chemotherapy group on AALL1331 compared with previous studies was likely related to differences in the intensity of CNS-directed therapy. Both COG AALL02P2 and POG 9412 regimens used 24 high-dose cytarabine (3 g/m2) doses. In AALL1331, the chemotherapy arm included eight high-dose cytarabine doses, while the blinatumomab arm contained none. COG AALL02P2 used eight MTX 5 g/m2 doses, and POG 9412 used eight MTX 1 g/m2 doses. AALL1331 used 1 g/m2 of MTX, given four times in the chemotherapy arm and three times in the blinatumomab arm. In UKALLR3, most patients with late CNS relapse underwent HSCT and only 11 were treated with chemotherapy without HSCT. While these patients had an excellent 3-year EFS of 90.9%, this very small number of patients also received 24 Gy CRT at week 14 of therapy, eight high-dose cytarabine doses, and two MTX 1 g/m2 doses. The UKALLR3 24 Gy CRT dose is higher than used in either AALL1331 or POG 9412 (18 Gy in both). Indeed, COG AALL02P2 was terminated early because of inferior outcomes with only 12 Gy CRT. Given the poor outcome for iCNS relapse patients in both AALL1331 treatment arms and the known adverse effects of higher-dose CRT, this subset of patients urgently needs more effective therapy. For patients with isolated testicular disease, treatment arm did not affect outcome and the small number of patients did very well with or without blinatumomab.

Similar to the AALL1331 high-risk and IR patients, blinatumomab was well tolerated in LR patients with significantly lower rates of severe hematologic and infectious toxicity compared with the more intense blocks of chemotherapy18 despite the 28-day continuous intravenous access and infusion for patients receiving blinatumomab. There were low rates of CRS and neurotoxicity from blinatumomab and these were almost always <grade 3. All blinatumomab-related AEs were fully reversible and only two (1.6%) patients discontinued study because of blinatumomab-related AEs.

Recent major advances in ALL therapy include the immunotherapies blinatumomab, inotuzumab, and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. All are well tolerated and highly active in relapsed/refractory pediatric and are being investigated in newly diagnosed patients.

In conclusion, AALL1331 establishes that blinatumomab improves DFS and OS for children, adolescents, and young adults with LR first B-ALL BM relapse with or without EM disease, defining a new standard of care for these patients. However, LR patients with iCNS relapse fared poorly with or without blinatumomab, and different treatment strategies for this group are urgently needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

E.A.R. is a KiDS of NYU Foundation Professor at NYU Langone Health. S.P.H. is the Jeffrey E. Perelman Distinguished Chair in Pediatrics at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. M.L.L. is the Aldarra Foundation, June and Bill Boeing Founders, Endowed Chair in Pediatric Cancer Research of Seattle Children's Hospital.

APPENDIX

FIG A1.

(A) DFS and (B) OS of LR patients with isolated marrow relapse. (C) DFS and (D) OS of low-risk patients with marrow plus EM. DFS, disease-free survival; EM, extramedullary; OS, overall survival.

FIG A2.

(A) DFS and (B) OS of low-risk patients with iCNS relapse. (C) DFS and (D) OS of low-risk patients with iTesticular relapse. DFS, disease-free survival; iCNS, isolated CNS; IEM, isolated extramedullary; iTesticular, isolated testicular; OS, overall survival.

TABLE A1.

Block 1 Reinduction Chemotherapy

TABLE A2.

Postreinduction Therapy

TABLE A3.

CNS Status at Initial Diagnosis by Site of First Relapse

TABLE A4.

Comparison of Site of First Relapse Versus Sites of Second Relapse

Patrick A. Brown

Employment: Bristol Myers Squibb

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Bristol Myers Squibb

Lingyun Ji

This author is a member of the Journal of Clinical Oncology Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda

Meenakshi Devidas

This author is a member of the Journal of Clinical Oncology Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Honoraria: Novartis, Merck

Michael J. Borowitz

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blueprint Medicines

Research Funding: Becton Dickinson

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Beckman Coulter

Elizabeth A. Raetz

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Other Relationship: BMS

Gerhard Zugmaier

Employment: Amgen

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amgen

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Multiple patents

Melanie B. Bernhardt

Consulting or Advisory Role: BTG, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Lia Gore

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amgen, Sanofi, Mirati Therapeutics, OnKure

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Amgen, Roche/Genentech, Syndax, OnKure, Janssen Oncology, Pfizer

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent held for diagnostic discovery and treatment response methodology tools in the use of MR spectroscopy for leukemia

Uncompensated Relationships: Kestrel Therapeutics

James A. Whitlock

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Syndax (Inst)

Stephen P. Hunger

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amgen, Merck

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Servier/Pfizer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

See accompanying Oncology Grand Rounds, p. 4087

DISCLAIMER

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the 2019 American Society of Hematology Meeting, Orlando, FL, December 7-10, 2019; and at the 2021 American Society of Hematology Meeting, virtual, December 11-14, 2021.

SUPPORT

Supported by NCTN Operations Center Grant U10CA180886, NCTN Statistics & Data Center Grant U10CA180899, St Baldrick’s Foundation. Blinatumomab was provided to study participants by Amgen via a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement with the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute/Cancer Therapy and Evaluation Program.

CLINICAL TRIAL INFORMATION

NCT02101853 (COG AALL1331)

L.E.H. and P.A.B. are co-first authors and S.P.H. and M.L.L. are co-senior authors.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

The Children's Oncology Group Data Sharing policy describes the release and use of COG individual subject data for use in research projects in accordance with National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) Program and NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Guidelines. Only data expressly released from the oversight of the relevant COG Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) are available to be shared. Data sharing will ordinarily be considered only after the primary study manuscript is accepted for publication. For phase 3 studies, individual-level de-identified datasets that would be sufficient to reproduce results provided in a publication containing the primary study analysis can be requested from the NCTN/NCORP Data Archive at https://nctn-data-archive.nci.nih.gov/. Data are available to researchers who wish to analyze the data in secondary studies to enhance the public health benefit of the original work and agree to the terms and conditions of use. For non-phase 3 studies, data are available following the primary publication. An individual-level de-identified dataset containing the variables analyzed in the primary results paper can be expected to be available upon request. Requests for access to COG protocol research data should be sent to: datarequest@childrensoncologygroup.org. Data are available to researchers whose proposed analysis is found by COG to be feasible and of scientific merit and who agree to the terms and conditions of use. For all requests, no other study documents, including the protocol, will be made available and no end date exists for requests. In addition to above, release of data collected in a clinical trial conducted under a binding collaborative agreement between COG or the NCI Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) and a pharmaceutical/biotechnology company must comply with the data sharing terms of the binding collaborative/contractual agreement and must receive the proper approvals.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Laura E. Hogan, Patrick A. Brown, Lingyun Ji, Meenakshi Devidas, Elizabeth A. Raetz, Gerhard Zugmaier, Elad Sharon, Stephanie A. Terezakis, Lia Gore, James A. Whitlock, Stephen P. Hunger, Mignon L. Loh

Collection and assembly of data: Laura E. Hogan, Patrick A. Brown, Lingyun Ji, Xinxin Xu, Meenakshi Devidas, Andrew Carroll, Nyla A. Heerema, Lia Gore, Stephen P. Hunger, Mignon L. Loh

Data analysis and interpretation: Laura E. Hogan, Patrick A. Brown, Lingyun Ji, Xinxin Xu, Meenakshi Devidas, Teena Bhatla, Michael J. Borowitz, Elizabeth A. Raetz, Gerhard Zugmaier, Elad Sharon, Melanie B. Bernhardt, Stephanie A. Terezakis, Lia Gore, James A. Whitlock, Stephen P. Hunger, Mignon L. Loh

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Children's Oncology Group AALL1331: Phase III Trial of Blinatumomab in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With Low Risk B-Cell ALL in First Relapse

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Patrick A. Brown

Employment: Bristol Myers Squibb

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Bristol Myers Squibb

Lingyun Ji

This author is a member of the Journal of Clinical Oncology Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda

Meenakshi Devidas

This author is a member of the Journal of Clinical Oncology Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Honoraria: Novartis, Merck

Michael J. Borowitz

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blueprint Medicines

Research Funding: Becton Dickinson

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Beckman Coulter

Elizabeth A. Raetz

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Other Relationship: BMS

Gerhard Zugmaier

Employment: Amgen

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amgen

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Multiple patents

Melanie B. Bernhardt

Consulting or Advisory Role: BTG, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Lia Gore

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amgen, Sanofi, Mirati Therapeutics, OnKure

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Amgen, Roche/Genentech, Syndax, OnKure, Janssen Oncology, Pfizer

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent held for diagnostic discovery and treatment response methodology tools in the use of MR spectroscopy for leukemia

Uncompensated Relationships: Kestrel Therapeutics

James A. Whitlock

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Syndax (Inst)

Stephen P. Hunger

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amgen, Merck

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Servier/Pfizer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bhojwani D, Pui CH. Relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e205–e217. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70580-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1541–1552. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1400972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ko RH, Ji L, Barnette P, et al. Outcome of patients treated for relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Therapeutic Advances in Childhood Leukemia Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:648–654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freyer DR, Devidas M, La M, et al. Postrelapse survival in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is independent of initial treatment intensity: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood. 2011;117:3010–3015. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horton TM, Whitlock JA, Lu X, et al. Bortezomib reinduction chemotherapy in high-risk ALL in first relapse: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Br J Haematol. 2019;186:274–285. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nguyen K, Devidas M, Cheng SC, et al. Factors influencing survival after relapse from acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Children's Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 2008;22:2142–2150. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oskarsson T, Söderhäll S, Arvidson J, et al. Relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the Nordic countries: Prognostic factors, treatment and outcome. Haematologica. 2016;101:68–76. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.131680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parker C, Waters R, Leighton C, et al. Effect of mitoxantrone on outcome of children with first relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL R3): An open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:2009–2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raetz EA, Cairo MS, Borowitz MJ, et al. Re-induction chemoimmunotherapy with epratuzumab in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): Phase II results from Children's Oncology Group (COG) study ADVL04P2. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1171–1175. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tallen G, Ratei R, Mann G, et al. Long-term outcome in children with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia after time-point and site-of-relapse stratification and intensified short-course multidrug chemotherapy: Results of trial ALL-REZ BFM 90. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2339–2347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coustan-Smith E, Gajjar A, Hijiya N, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia after first relapse. Leukemia. 2004;18:499–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eckert C, Biondi A, Seeger K, et al. Prognostic value of minimal residual disease in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2001;358:1239–1241. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Locatelli F, Schrappe M, Bernardo ME, et al. How I treat relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:2807–2816. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-265884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paganin M, Zecca M, Fabbri G, et al. Minimal residual disease is an important predictive factor of outcome in children with relapsed 'high-risk' acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:2193–2200. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von Stackelberg A, Locatelli F, Zugmaier G, et al. Phase I/phase II study of blinatumomab in pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4381–4389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gökbuget N, et al. Blinatumomab versus chemotherapy for advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:836–847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gökbuget N, Dombret H, Bonifacio M, et al. Blinatumomab for minimal residual disease in adults with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2018;131:1522–1531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-08-798322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown PA, Ji L, Xu X, et al. Effect of postreinduction therapy consolidation with blinatumomab vs chemotherapy on disease-free survival in children, adolescents, and young adults with first relapse of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:833–842. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: A Children's Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111:5477–5485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eckert C, Groeneveld-Krentz S, Kirschner-Schwabe R, et al. Improving stratification for children with late bone marrow B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapses with refined response classification and integration of genetics. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3493–3506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lew G, Chen Y, Lu X, et al. Outcomes after late bone marrow and very early central nervous system relapse of childhood B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Children's Oncology Group phase III study AALL0433. Haematologica. 2020;106:46–55. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.237230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parker C, Krishnan S, Hamadeh L, et al. Outcomes of patients with childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with late bone marrow relapses: Long-term follow-up of the ALLR3 open-label randomised trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e204–e216. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30003-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lan KKG, DeMets DL. Discrete sequential boundaries for clinical trials. Biometrika. 1983;70:659–663. [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Freidlin B, Korn EL. A comment on futility monitoring. Controlled Clin Trials. 2002;23:355–366. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. ed 2. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Nizam A, et al. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods (ed 5). Belmont, CA, Duxbury Press/Cengage Learning. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LLC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barredo JC, Devidas M, Lauer SJ, et al. Isolated CNS relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with intensive systemic chemotherapy and delayed CNS radiation: A pediatric oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3142–3149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hastings C, Chen Y, Devidas M, et al. Late isolated central nervous system relapse in childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with intensified systemic therapy and delayed reduced dose cranial radiation: A report from the Children's Oncology Group study AALL02P2. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68:e29256. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The Children's Oncology Group Data Sharing policy describes the release and use of COG individual subject data for use in research projects in accordance with National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) Program and NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Guidelines. Only data expressly released from the oversight of the relevant COG Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) are available to be shared. Data sharing will ordinarily be considered only after the primary study manuscript is accepted for publication. For phase 3 studies, individual-level de-identified datasets that would be sufficient to reproduce results provided in a publication containing the primary study analysis can be requested from the NCTN/NCORP Data Archive at https://nctn-data-archive.nci.nih.gov/. Data are available to researchers who wish to analyze the data in secondary studies to enhance the public health benefit of the original work and agree to the terms and conditions of use. For non-phase 3 studies, data are available following the primary publication. An individual-level de-identified dataset containing the variables analyzed in the primary results paper can be expected to be available upon request. Requests for access to COG protocol research data should be sent to: datarequest@childrensoncologygroup.org. Data are available to researchers whose proposed analysis is found by COG to be feasible and of scientific merit and who agree to the terms and conditions of use. For all requests, no other study documents, including the protocol, will be made available and no end date exists for requests. In addition to above, release of data collected in a clinical trial conducted under a binding collaborative agreement between COG or the NCI Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) and a pharmaceutical/biotechnology company must comply with the data sharing terms of the binding collaborative/contractual agreement and must receive the proper approvals.