Abstract

PURPOSE

To describe the supply of cancer specialists, the organization of cancer care within versus outside of health systems, and the distance to multispecialty cancer centers.

METHODS

Using the 2018 Health Systems and Provider Database from the National Bureau of Economic Research and 2018 Medicare data, we identified 46,341 unique physicians providing cancer care. We stratified physicians by discipline (adult/pediatric medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, surgical/gynecologic oncologists, other surgeons performing cancer surgeries, or palliative care physicians), system type (National Cancer Institute [NCI] Cancer Center system, non-NCI academic system, nonacademic system, or nonsystem/independent practice), practice size, and composition (single disciplinary oncology, multidisciplinary oncology, or multispecialty). We computed the density of cancer specialists by county and calculated distances to the nearest NCI Cancer Center.

RESULTS

More than half of all cancer specialists (57.8%) practiced in health systems, but 55.0% of cancer-related visits occurred in independent practices. Most system-based physicians were in large practices with more than 100 physicians, while those in independent practices were in smaller practices. Practices in NCI Cancer Center systems (95.2%), non-NCI academic systems (95.0%), and nonacademic systems (94.3%) were primarily multispecialty, while fewer independent practices (44.8%) were. Cancer specialist density was sparse in many rural areas, where the median travel distance to an NCI Cancer Center was 98.7 miles. Distances to NCI Cancer Centers were shorter for individuals living in high-income areas than in low-income areas, even for individuals in suburban and urban areas.

CONCLUSION

Although many cancer specialists practiced in multispecialty health systems, many also worked in smaller-sized independent practices where most patients were treated. Access to cancer specialists and cancer centers was limited in many areas, particularly in rural and low-income areas.

INTRODUCTION

In 2013, the Institute of Medicine declared that the cancer care delivery system was in crisis because it frequently provided care that was not patient-centered, evidence-based, or accessible to vulnerable and underserved populations.1 Patients with cancer often require multidisciplinary care from medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists or other surgeons, as well as palliative care physicians. In addition, some patients with cancer may benefit from very specialized care, such as bone marrow transplants, highly complex surgeries, and clinical trials of investigational therapies.

Health systems that are organized and managed to integrate cancer care present one avenue to improving quality and patient-centered care for patients with cancer. Because of their scale and scope, health systems may have advantages compared with independent practices. For example, they may have greater accessibility to capital for infrastructure investments (eg, health information technology), more effective channels to diffuse knowledge and enhanced strategies to deliver guideline-concordant care (eg, clinical pathways), and greater implementation of processes to coordinate care and reduce waste. Previous research has reported higher survival rates among patients newly diagnosed with specific cancers treated at National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Centers or high-volume centers compared with other facilities.2,3 However, larger systems resulting from consolidation can also be associated with worse patient experiences and mixed outcomes.4,5

CONTEXT

Key Objective

What is the supply of cancer specialists in the United States and where do they practice?

Knowledge Generated

Although more than half of all cancer specialists practice in systems, 55% of cancer-related outpatient office visits and procedures provided to fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries are by cancer specialists practicing independently. Health system–based physician practices are larger and more likely to be multispecialty than independent practices are. Residents in rural and low-income areas have more limited access to cancer specialists and National Cancer Institute Cancer Centers.

Relevance (S.B. Wheeler)

-

These results clarify the current organizational context and specialty structures available to treat people with cancer living in diverse geographic regions across the US. The disproportionate distribution of oncology care providers in more urban and high-income communities may provide motivation for further investment in programs and policies that can attract oncology care providers to communities and practices serving rural, low-income, and other marginalized cancer patient populations.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Stephanie B. Wheeler, PhD, MPH.

To date, researchers have not comprehensively characterized specialists providing cancer care across the United States nor assessed the extent to which they practice within versus outside of health systems. ASCO regularly tracks the size, distribution, and diversity of the US oncology workforce with its National Oncology Census. However, this Census is limited by its focus on medical oncology practices, limited sample (<700), and reliance on self-reported data, making it susceptible to nonresponse bias and missing data for many small practices and some large academic institutions.6

Using a novel national database developed by members of the research team containing information on physicians, physician practices, hospitals, and health systems created from 20 public and proprietary data sources, we describe the oncology physician workforce and the cancer care delivery systems in which cancer specialists practice. Specifically, we identify all physicians with a primary or secondary specialty of medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgical/gynecologic oncology, or hospice and palliative care. We also identify other surgeons (eg, urologists and general and colorectal surgeons) performing cancer surgeries for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. We further investigate three types of cancer care delivery systems (NCI Cancer Center systems, non-NCI academic systems, and nonacademic health systems) and nonsystem/independent practices. In this article, we describe (1) the organization of cancer care within versus outside of health systems and (2) patient access to cancer specialists and NCI Cancer Centers.

METHODS

Data

The Health Systems and Provider Database (HSPD)7 was created as part of an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) initiative on Health System Organization and Performance. It combined multiple data sources (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] administrative and claims data, tax and financial records, and proprietary sources) to link health care physicians actively engaged in delivering patient care and their practice organizations, institutional organizations such as hospitals and postacute care facilities, and health systems in 2018 (Data Supplement [Appendix]).

Health Systems

We classified physician practices with at least one cancer specialist as (1) NCI Cancer Center systems, (2) non-NCI academic systems, (3) nonacademic health systems (neither NCI Cancer Center nor academic), or (4) independent. First, we considered all practices associated with an NCI Cancer Center or academic medical center, regardless of size, to be in systems. Next, we identified non-NCI and nonacademic systems using the HSPD definition of a health system: any set of commonly owned or managed physician organizations with at least one nonfederal general acute care hospital, at least 50 physicians, and at least 10 physicians providing primary care (Data Supplement [Appendix]). Finally, we classified the remaining practices as independent (Data Supplement [Appendix]).

Cancer Specialists

We identified 46,341 physicians with either a primary or secondary specialty of oncology (medical [including hematology and pediatric], radiation, surgical/gynecologic) or hospice and palliative care using specialty information from the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty database and National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (Data Supplement [Table S1]).8 We used a 20% sample of fee-for-service Medicare claims data to identify other surgeons who performed at least one cancer surgery for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries during 2018 (Data Supplement [Appendix]). Documented sex and graduation year were available for 46,341 (100%) and 40,111 (86.6%) cancer specialists, respectively.

Physician Practices

We identified a physician practice as the set of physicians billing under a common tax identification number. When a physician billed under more than one practice, we assigned an equal proportion of the physician's full-time equivalent to each practice (eg, a physician billing under two different practices was counted as 0.5 at each). Most cancer specialists were affiliated with one (50.5%), two (21.4%), or three (21.4%) practices.

To characterize practice specialty composition, we classified practices as (1) single disciplinary oncology (single oncology discipline and at least 60% of the practice's physicians were cancer specialists), (2) multidisciplinary oncology (two or more oncology disciplines and at least 60% of the practice's physicians were cancer specialists), or (3) multispecialty (all other practices with cancer and noncancer specialists).

Practice Sites

We used CMS Physician Compare and SK&A data to assign multisite practices to unique practice sites on the basis of ZIP code tabulation areas (ZCTAs). For each practice site, we used ZCTA to link poverty-level data from the American Community Survey and urban/suburban/rural classifications corresponding to geographic distinctions in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (Data Supplement [Appendix]).9 Consistent with previous research,9-12 we defined a ZCTA as low income if its proportion of individuals with income ≤200% of the federal poverty-level (FPL) fell into the top decile of the national distribution (57.4%-100% of the population with income ≤200% of the FPL). ZCTAs were classified as high income if its proportion of individuals with income ≥500% of the FPL was in the top decile of the national distribution (43.0%-100% of the population with income ≥500% of the FPL).

For geographic analyses, we assigned physicians practicing at more than one site of a multisite practice an equal proportion to each ZIP code in which the sites were located (ie, a physician practicing in four different ZIP codes was counted as 0.25 in each). Most cancer specialists practiced in one (79.4%), two (13.9%), or three (3.3%) ZIP codes. We did this attribution at the ZIP code level before aggregating it up to the ZCTA and county level because one ZCTA can contain multiple ZIP codes.

Analysis

We described the number of cancer specialists overall and by discipline (medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgical/gynecologic oncology, other surgery performing cancer surgeries, or hospice and palliative care). We stratified oncologist disciplines by system type (including nonsystem/independent), practice size, and practice specialty composition.

We computed the number of face-to-face office visits for evaluation and management services (Current Procedural Terminology codes 99201-99215) provided to fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries by oncology discipline and system type. We calculated the density of cancer specialists per 100,000 population in each US county and the geodetic distances (the shortest distance between two points on a sphere) from each ZCTA centroid to the nearest NCI Cancer Center. Grouping ZCTAs on the basis of geography (urban/suburban/rural) and income (low/high), we also computed median distances for each category to the nearest NCI Cancer Center.

RESULTS

Distribution of Cancer Specialists in Systems and Practice Composition

We identified 46,341 cancer specialists, including 26,841 physicians with a primary or secondary specialty of oncology (18,302 adult/pediatric medical, 5,459 radiation, and 3,080 surgical/gynecologic), 1,759 palliative care physicians, and 18,879 other surgeons performing cancer surgeries in 2018. A small number of cancer specialists (N = 1,133, 2.4%) were classified under more than one oncology discipline (Data Supplement [Table S2]). Of these physicians, 71.8% were male; their mean number of years since medical school graduation was 23.3 (standard deviation, 11.4; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Physician Characteristics by Oncology Discipline

Overall, 57.8% of cancer specialists practiced in health systems, with 23.2% in NCI Cancer Center or other academic systems (Fig 1A). Distribution by system type varied modestly across disciplines. Surgical oncologists were most likely to practice in NCI Cancer Center systems (23.3%), and other surgeons performing cancer surgeries were least likely (12.0%). More than 25% of medical oncologists were in non-NCI academic systems, while 40.6% were in independent practices. Radiation oncologists were more likely than other types to work in independent practices (48.2%), with smaller percentages in nonacademic systems (29.6%), NCI Cancer Center systems (17.0%), and non-NCI academic systems (5.2%). Most palliative care physicians were in nonacademic systems (45.1%) and independent practices (30.4%).

FIG 1.

Distribution of cancer specialists by discipline and system type. (A-C) Physicians were counted using their full-time equivalents. For example, a physician who was part of two different practices was counted as 0.5 at each. (A and C) Other cancer surgeons refer to surgeons other than surgical or gynecologic oncologists who performed cancer-directed surgeries for Medicare patients. (B and C) A physician can work less than one full-time equivalent in a particular practice, but we used the minimum labels of 1 physician for ease of interpretation. (C) Single discipline oncology and multidisciplinary oncology practices were composed of at least 60% cancer specialists; multispecialty practices were all other practices with cancer and noncancer specialists. NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Overall, the median number of physicians in a practice was 100. There were substantial differences in practice size for cancer specialists within versus outside of systems (Fig 1B). Nearly all cancer specialists in NCI Cancer Center systems were in very large practices with more than 200 physicians (91.9%). Similarly, most cancer specialists in other academic systems (89.1%) and nonacademic systems (63.2%) were in large practices with more than 100 physicians. By contrast, many cancer specialists practicing independently were in small practices with 10 or fewer physicians (25.6%) and 11-50 physicians (16.6%). These findings for cancer specialists are consistent with the practice sizes of physicians across all medical specialties.5

There were also notable differences in the composition of oncology practices for physicians working within versus outside of systems (Fig 1C). System-based cancer specialists were likely to practice in multispecialty practices that also included noncancer specialists (about 95%). While many cancer specialists in independent practices were in multispecialty practices (44.8%), others practiced in single disciplinary oncology practices (eg, medical oncologists [17.5%], other surgeons performing cancer surgeries [14.2%]) or multidisciplinary practices with at least one medical oncologist, one radiation oncologist, and one surgical oncologist or other surgeon performing cancer surgeries (11.2%). The Data Supplement ([Table S3]) displays practice size by oncologist type.

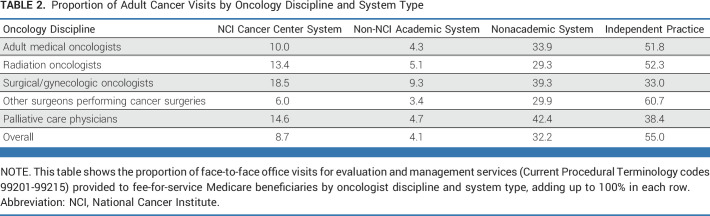

Among all office visits to cancer specialists by fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in 2018, only 12.8% were to cancer specialists in academic health systems (NCI or non-NCI), compared with 32.2% to cancer specialists in nonacademic systems and 55.0% to cancer specialists in independent practices (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Proportion of Adult Cancer Visits by Oncology Discipline and System Type

Cancer Specialist Density and Distance to NCI Cancer Centers

The number of cancer specialists ranged from 0 to 235 cancer specialists per 100,000 population across US counties (Fig 2A). Cancer specialist supply (excluding palliative care physicians) was low in many rural areas. The distribution of the county-level density of cancer specialists by discipline was consistent with the relative proportion of each type of specialist (Data Supplement [Table S4]). The density of palliative care physicians was particularly sparse in areas of the Midwest and South (Fig 2B).

FIG 2.

Density of cancer specialists per 100,000 population by county. (A) Excluded palliative care physicians. When a physician practiced in more than one ZIP code, we assigned an equal proportion to each ZIP code (ie, a physician practicing in four different ZIP codes was counted as 0.25 in each). We did this attribution at the ZIP code level before aggregating it up to the ZCTA and county level because one ZCTA can contain multiple ZIP codes. ZCTA, ZIP code tabulation area.

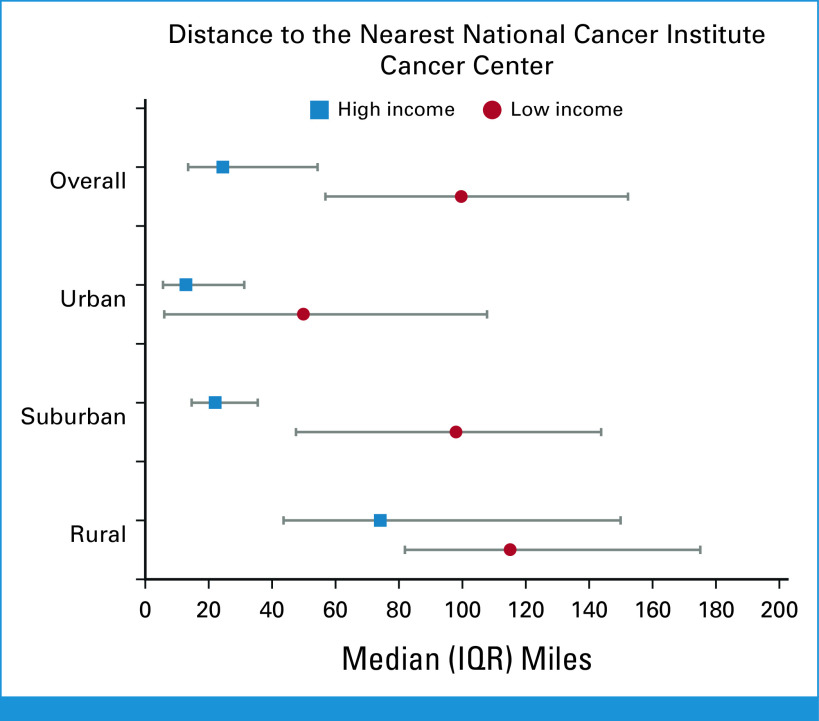

NCI Cancer Centers were concentrated in the eastern half of the United States. Travel distances to an NCI Cancer Center were much greater for residents in rural areas (median of 98.7 miles [IQR, 63.8-153.7]) than for those in urban (49.2 miles [IQR, 10.1-103.8]) and suburban (53.3 miles [IQR, 24.8-99.1]) areas (Fig 3). For example, although many counties in Montana had more than 15 oncologists per 100,000 population, the distance to the nearest NCI Cancer Center was more than 295 miles for most residents.

FIG 3.

Distance to the nearest National Cancer Institute Cancer Center.

Distance to an NCI Cancer Center also varied by area-level income. Individuals living in high-income areas traveled much shorter distances to reach an NCI Cancer Center than those in low-income areas (Fig 4), even in suburban and urban areas. In addition, there was greater variation in distance for individuals in rural and low-income areas.

FIG 4.

Distribution of distances from the ZIP code tabulation area centroid to the nearest National Cancer Institute Cancer Center by geography and income.

DISCUSSION

In this national study, we found that 40.6% of cancer specialists practiced in independent groups (mostly in small practices with 50 or fewer physicians) and 59.4% practiced in health systems (mostly in large practices with more than 100 physicians). Among specialists practicing in health systems, about 40% were affiliated with an NCI Cancer Center or other academic system, and about 60% were affiliated with nonacademic systems. Although fewer than half of all cancer specialists were in independent practices, they provided 55.0% of all outpatient office visits and procedures to fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in 2018. By contrast, cancer specialists in academic systems (NCI or non-NCI) constituted 23.2% of the oncology physician workforce and provided only 12.8% of patient visits and procedures. Academic cancer specialists may provide less care because their responsibilities also include research and education.

We also documented differences in the organization and composition of practices within versus outside of health systems. For example, system-based cancer specialists typically practiced in very large-sized multispecialty practices. Independent cancer specialists more often practiced in smaller sized practices that were multispecialty, multidisciplinary oncology, or single disciplinary oncology.

Previous research has found some evidence of higher survival rates among patients newly diagnosed with specific cancers or enrolled in clinical trials and treated at NCI Cancer Centers compared with other institutions.2,13-15 This may be because cancer care is complex and often requires varied expertise and treatment. With multiple specialties present in health systems, there may be more opportunities for coordination of cancer care across different oncology disciplines or treatment modalities within one setting. Despite this promise, evidence has shown few differences in clinical quality and patient experience in systems versus nonsystems.7

Cancer incidence and mortality rates are beset by inequities among patients with cancer by race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and rural residence,16,17 and access to appropriate physicians and services can be critical to how and whether patients with cancer receive care.18-20 Consistent with previous research,21 we found that certain areas had both low densities of cancer specialists and large distances from NCI Cancer Centers. In addition, there were areas with high numbers of cancer specialists per population that were far from the nearest NCI Cancer Center, and vice versa. Some patients may seek care locally for convenience despite the availability of more specialized care at a regional center.22 It is difficult to predict how individual patients may weigh the relative benefits of traveling farther to see cancer specialists in a large health system or NCI Cancer Center. The disproportionate density of cancer specialists around NCI Cancer Centers may limit accessibility to cancer care for patients living further away, a particular concern for patients with rare cancers or those who require more complex treatments or might benefit from enrollment in clinical trials. As community hospitals increasingly refer patients with cancer to NCI Cancer Centers and other academic systems,23 it is important to consider distance.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to comprehensively identify and characterize the oncology physician workforce across the United States. While ASCO regularly surveys medical oncology practices, we identified the broader group of cancer specialists by including radiation oncologists, surgical oncologists, and other surgeons performing cancer surgeries. Additionally, we studied palliative care physicians, who provide important contributions to cancer care. Previous work has shown that patients who receive early palliative care integrated with standard oncologic care have improved patient outcomes, quality of life, and mood compared with those who receive standard oncologic care alone.24-26 In this study, we found that palliative care physicians were part of multispecialty and multidisciplinary oncology teams across all practice types. Their density was high near NCI Cancer Centers but sparse in other parts of the country, and they provided a high proportion of their care in nonacademic and independent practices.

This study has several limitations. First, we were unable to compute physicians' true full-time equivalent efforts. We estimated physicians' efforts on the basis of the number of practices to which they billed for care rather than how their hours were distributed or the number of hours devoted to clinical care. This likely disproportionately affected cancer specialists in NCI Cancer Center systems and other academic systems who may allocate a considerable amount of their workday to teaching and research and thus spend less time with patients with cancer than community cancer specialists. Second, we used geodetic distances instead of travel times to measure access from a ZCTA centroid to the nearest NCI Cancer Center. We considered both density of cancer specialists and location of NCI Cancer Centers because access is not necessarily consistent regarding supply versus distance. Third, we identified surgeons providing cancer surgeries on the basis of fee-for-service Medicare claims and did not observe surgeons who provided care exclusively to patients enrolled in Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, or commercial plans. Fourth, the percentages of cancer visits were based solely on fee-for-service Medicare claims and may not be representative. Finally, we did not consider the quality or cost of care provided within and outside of systems27 because it was out of the scope of this study.

We found that cancer specialists in NCI Cancer Centers and other academic systems practiced in large, multispecialty practices, while independent cancer specialists practiced in smaller multispecialty, multidisciplinary oncology, or single disciplinary oncology practices. Larger practices may be associated with efforts to advance scientific leadership, resources, and research in cancer care delivery systems. They may also increase the likelihood of having cancer specialists with more specialized expertise, such as in rare tumors or complex surgeries. However, there is a disconnect between where systems are located, where cancer specialists practice, and where patients receive care. For example, there is a higher density of cancer specialists near NCI Cancer Centers, but many patients live far away and receive care in independent practices. Increasing the number of cancer specialists and expanding centers of innovation in low-density areas could help equalize access to care.

Changing marketplace dynamics and patient behaviors can complicate the standardization and integration of care. The organization of cancer care differs within versus outside of health systems, and proximity to a large NCI Cancer Center does not necessarily imply a high cancer specialist density. As the demand for oncology care outpaces cancer specialist supply,28 physician practices may benefit from advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Incorporating such clinicians into oncology teams can improve clinical outcomes and relieve the stress on cancer specialists.29-31 It is important that policies regarding financial and structural support for cancer research and treatment consider the organization of cancer specialists and delivery systems in the United States, as well as how it may change due to external factors, including practice acquisitions32 and payment and delivery programs, such as the CMS Oncology Care Model, 340B Drug Pricing Program, and shift of surgery to the outpatient setting.

Nancy D. Beaulieu

Research Funding: Ballad Health (Inst)

Alexi A. Wright

Consulting or Advisory Role: GlaxoSmithKline, Cancer Support Community, Merck

Research Funding: NCCN/AstraZeneca (Inst), Pack Health (Inst)

David M. Cutler

Expert Testimony: MDL—Opioids, MDL—JUUL

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ or the NCI.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Celebration of Early Career Investigators in Cancer Research, Boston, MA, December 12, 2018; the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Comparative Health System Performance Initiative Annual Workshop, Rockville, MD, September 25, 2018; the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, New Orleans, LA, June 25, 2017.

SUPPORT

Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) under award number 1U19HS024072 and the National Cancer Institute (NIH) under award number R01CA255035.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Financial support: David M. Cutler

Administrative support: Christina A. Nguyen

Collection and assembly of data: Christina A. Nguyen, Nancy D. Beaulieu, David M. Cutler, Nancy L. Keating, Mary Beth Landrum

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Organization of Cancer Specialists in US Physician Practices and Health Systems

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Nancy D. Beaulieu

Research Funding: Ballad Health (Inst)

Alexi A. Wright

Consulting or Advisory Role: GlaxoSmithKline, Cancer Support Community, Merck

Research Funding: NCCN/AstraZeneca (Inst), Pack Health (Inst)

David M. Cutler

Expert Testimony: MDL—Opioids, MDL—JUUL

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wolfson JA, Sun CL, Wyatt LP, et al. Impact of care at comprehensive cancer centers on outcome: Results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2015;121:3885–3893. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Merkow RP, Yang AD, Pavey E, et al. Comparison of hospitals affiliated with PPS-exempt cancer centers, other hospitals affiliated with NCI-designated cancer centers, and other hospitals that provide cancer care. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1043–1051. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaynor M, Town R. The Impact of Hospital Consolidation—Update. Princeton, NJ, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: The Synthesis Project; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beaulieu ND, Dafny LS, Landon BE, et al. Changes in quality of care after hospital mergers and acquisitions. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:51–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1901383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Society of Clinical Oncology The state of cancer care in America, 2016: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. JCO Oncol Pract. 2016;12:339–383. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.010462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beaulieu ND, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM, et al. Organization and performance of US health systems. JAMA. 2023;329:325–335. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.24032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Warren JL, Barrett MJ, White DP, et al. Sensitivity of Medicare data to identify oncologists. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2020;2020:60–65. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgz030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nguyen CA, Chernew ME, Ostrer I, et al. Comparison of Healthcare delivery systems in low- and high-income communities. Am J Accountable Care. 2019;7:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, et al. Income inequality and mortality in metropolitan areas of the United States. Am J Pub Health. 1998;88:1074–1080. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.7.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, et al. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Short PF, Lefkowitz DC. Encouraging preventive services for low-income children: The effect of expanding Medicaid. Med Care. 1992;30:766–780. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Unger JM, LeBlanc M, George S, et al. Population, clinical, and scientific impact of National Cancer Institute's National Clinical Trials Network treatment studies. J Clin Oncol. 2023;30:2020–2028. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, et al. Influence of NCI cancer center attendance on mortality in lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66:542–560. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bristow RE, Chang J, Ziogas A, et al. Impact of National Cancer Institute comprehensive cancer centers on ovarian cancer treatment and survival. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:940–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh GK, Jemal A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950–2014: Over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J Environ Pub Health. 2017;2017:1–19. doi: 10.1155/2017/2819372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O’Keefe EB, Meltzer JP, Bethea TN. Health disparities and cancer: Racial disparities in cancer mortality in the United States, 2000–2010. Front Public Health. 2015;3:51. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scoggins JF, Fedorenko CR, Donahue SMA, et al. Is Distance to provider a barrier to care for medicaid patients with breast, colorectal, or lung cancer? J Rural Health. 2012;28:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00371.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin CC, Bruinooge SS, Kirkwood MK, et al. Association between geographic access to cancer care, insurance, and receipt of chemotherapy: Geographic distribution of oncologists and travel distance. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3177–3185. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rocque GB, Williams CP, Miller HD, et al. Impact of travel time on health care costs and resource use by phase of care for older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1935–1945. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu Y, Fu C, Onega T, et al. Disparities in geographic accessibility of national cancer Institute cancer centers in the United States. J Med Syst. 2017;41:203. doi: 10.1007/s10916-017-0850-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Finlayson SRG, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson ANA, et al. Patient preferences for location of care: Implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37:204–209. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frosch ZAK, Illenberger N, Mitra N, et al. Trends in patient volume by hospital type and the association of these trends with time to cancer treatment initiation. JAMA Netw. 2021;4:e2115675. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;30:394–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takvorian SU, Yasaitis L, Liu M, et al. Differences in cancer care expenditures and utilization for surgery by hospital type among patients with private insurance. JAMA Netw. 2021;4:e2119764. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang W, Williams JH, Hogan PF, et al. Projected supply of and demand for oncologists and radiation oncologists through 2025: An aging, better-insured population will result in shortage. JCO Oncol Pract. 2014;10:39–45. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reynolds RB, McCoy K. The role of Advanced Practice Providers in interdisciplinary oncology care in the United States. Chin Clin Oncol. 2016;5:44. doi: 10.21037/cco.2016.05.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bruinooge SS, Pickard TA, Vogel W. Understanding the role of advanced practice providers in oncology in the United States. JCO Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e518–e532. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Austin A, Jeffries K, Krause D, et al. A study of advanced practice provider staffing models and professional development opportunities at national comprehensive cancer network member institutions. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2021;12:717–724. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2021.12.7.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nikpay SS, Richards MR, Penson D. Hospital-physician consolidation accelerated in the past decade in cardiology, oncology. Health Aff. 2018;37:1123–1127. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]