Abstract

Background:

Being a carrier of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele is a clear risk factor for development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). On some neurocognitive tests, there are smaller differences between carriers and noncarriers, while other tests show larger differences.

Aims:

We explore whether the size of the difference between carriers and noncarriers is a function of how well the tests measure general intelligence, so whether there are Jensen effects.

Methods:

We used the method of correlated vectors on 441 Korean older adults at risk for AD and 44 with AD.

Results:

Correlations between APOE carriership and test scores ranged from −.05 to .11 (normal), and −.23 to .54 (AD). The differences between carriers and noncarriers were Jensen effects: r = .31 and r = .54, respectively.

Conclusion:

A composite neurocognitive score may show a clearer contrast between APOE carriers and noncarriers than a large number of scores of single neurocognitive tests.

Keywords: apolipoprotein E4, Alzheimer’s disease, neuropsychological tests, Korea

Introduction

Alzheimer

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by progressive impairment of activities of daily living, by deterioration of cognition and memory, and a number of behavioral and psychological disturbances. It is estimated that well over 35 million people worldwide suffer from this form of dementia. Dementia is also known to be the most important cause of disability in older adults, and its direct and indirect costs are very high.

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the deposition of amyloid and accumulation of tangles in neocortical regions of the brain, and these processes start decades prior to dementia onset. The AD-type brain changes are often found in people with mild cognitive dysfunction or even without any cognitive symptoms at all. The causes of AD are as yet not well understood, and an effective treatment to delay the onset and progression of AD is not at hand, 1 but research clearly shows that being an apolipoprotein E (APOE) carrier dramatically increases the risk of developing AD.

Neurocognitive Tests

Neurocognitive tests are widely used to evaluate cognitive function in patients with neurological disorders such as AD. In these cases, neuropsychological testing is typically used to evaluate the presence and severity of AD and to monitor the disease progression. Alzheimer’s disease leads to substantially lower scores on neurocognitive tests, and various studies have shown that being a carrier of the APOE ε4 allele is a clear risk factor for cognitive decline as measured by scores on neurocognitive tests.

General Intelligence (g)

In 1904, Spearman discovered that the various mental abilities in an intelligence quotient (IQ) test battery all correlated positively with each other and he referred to this as the positive manifold. 2 This means that when a test taker has a high score on a verbal test, you can not only predict that he will have a high score on other verbal tests but you can also predict higher scores on computational and spatial tests. This well-established empirical finding is generally considered to be evidence of a general factor across all measured abilities. The degree to which each of the variables is correlated with the factor that is common to all the variables in the analysis can be established using the method of factor analysis. This general factor manifests in individual differences on all mental tests, regardless of verbal, computational, or spatial content, and was termed g by Spearman. 3 Spearman’s g can be measured as the loading on the first unrotated factor in a principal axis factor analysis of a diverse set of IQ tests. 4 The total score on an IQ test is a combination of verbal, computational, and spatial skills and so measures the general factor of intelligence best, it has the highest g loading. Tests of reasoning have high g loadings and measure general intelligence quite well, and tests of perceptual speed where one quickly has to judge whether 2 simple shapes are identical have low g loadings, meaning that they measure general intelligence less well.

Hierarchical Intelligence Model

The IQ batteries with various mental tests are best described by hierarchical intelligence models, such as Johnson and Bouchard’s 5 -7 verbal, perceptual, and image rotation model of cognitive abilities. In Carroll’s 8 influential hierarchical intelligence model, the lowest level of the hierarchy consists of large numbers of specific tests and subtests. One level higher (stratum I) comprises the narrow abilities, including perceptual speed, visualization, memory span, verbal abilities, quantitative reasoning, and sequential reasoning. One level higher (stratum II) is occupied by the broad abilities of broad cognitive speediness or general psychomotor speed, broad retrieval ability, broad auditory perception, broad visual perception, general memory and learning, crystallized intelligence, and fluid intelligence. General intelligence or g is situated at the highest level of the hierarchy (stratum III).

Link Between Neuropsychological Test Scores and IQ Scores

Many studies show the substantial correlations between neuropsychological test scores and IQ test scores. 9 -13 Neuropsychological tests can be viewed as classical IQ tests, but classical IQ tests can also be conceptualized as neuropsychological tests. Broad intelligence batteries are designed to measure many different cognitive abilities, and because neuropsychological test batteries also measure many different cognitive abilities, the latter’s total score could be highly similar to the g score of an IQ battery. A recent study by Jahng et al reported findings from a popular Korean neuropsychological test battery, the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery-Core (SNSB-Core), which showed the manifold of positive correlations common for classical IQ batteries. 14 They also showed that a higher order, hierarchical model with a general cognitive score at the highest level gave a much better fit to the data than a nonhierarchical model that focused on the 5 classical domain scores of attention, language, visuospatial, memory, and frontal/executive functions. All this means that a higher order score can be computed for this neuropsychological battery that it is conceptually similar to the g score of an IQ battery. Jangh et al show that these tests clearly differ in the way they correlate with the total score, so they also differ in their g loadings, meaning that we can distinguish between higher g and lower g tests. 14 (p140, Table 3)

Table 3.

Means and SDs of 2 Groups on 16 SNSB Tests.a

| Normal | AD | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | ε4+ | ε4− | All | ε4+ | ε4− | |||||||

| Tests | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Digit Span Forward | 6.10 | 1.51 | 6.04 | 1.53 | 6.11 | 1.51 | 4.69 | 1.73 | 4.83 | 1.47 | 4.65 | 1.82 |

| Digit Span Backward | 3.65 | 0.99 | 3.58 | 0.85 | 3.66 | 1.02 | 2.54 | 1.10 | 2.00 | 1.22 | 2.65 | 1.07 |

| Rey CFT Copy score | 33.36 | 2.39 | 33.77 | 2.24 | 33.26 | 2.42 | 21.83 | 9.65 | 22.42 | 10.87 | 21.67 | 9.57 |

| SVLT Immediate Recall | 20.07 | 4.29 | 20.47 | 4.15 | 19.97 | 4.33 | 9.93 | 3.80 | 10.00 | 3.52 | 9.91 | 3.94 |

| SVLT Delayed Recall | 6.34 | 2.24 | 6.61 | 2.16 | 6.27 | 2.25 | 1.17 | 1.65 | 1.50 | 1.52 | 1.09 | 1.70 |

| SVLT Recognition | 21.15 | 1.80 | 21.21 | 1.78 | 21.14 | 1.81 | 15.83 | 2.99 | 15.83 | 4.26 | 15.83 | 2.69 |

| RCFT Immediate Recall | 15.39 | 6.42 | 15.64 | 5.81 | 15.32 | 6.57 | 4.41 | 3.85 | 6.67 | 5.06 | 3.80 | 3.33 |

| RCFT Delayed Recall | 15.20 | 5.92 | 15.57 | 5.71 | 15.10 | 5.97 | 3.44 | 4.30 | 4.25 | 5.14 | 3.21 | 4.15 |

| RCFT Recognition | 20.03 | 1.76 | 20.01 | 1.70 | 20.04 | 1.78 | 15.86 | 3.24 | 16.83 | 4.54 | 15.61 | 2.89 |

| COWAT Animal | 15.84 | 4.22 | 15.57 | 4.35 | 15.91 | 4.19 | 8.41 | 3.13 | 9.67 | 2.34 | 8.09 | 3.27 |

| StroopWordreading Time | 0.66 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 0.14 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 1.21 | 0.58 | 1.03 | 0.44 | 1.25 | 0.61 |

| StroopColorreading Time | 86.44 | 19.59 | 84.51 | 21.51 | 86.93 | 19.09 | 35.93 | 14.93 | 42.40 | 7.57 | 34.45 | 15.90 |

| K-MMSE | 27.76 | 1.69 | 27.57 | 1.66 | 27.80 | 1.70 | 20.45 | 6.08 | 21.67 | 5.16 | 20.13 | 6.36 |

| Naming (BNT) | 12.46 | 1.88 | 12.49 | 2.02 | 12.45 | 1.85 | 8.93 | 3.95 | 11.17 | 4.45 | 8.35 | 3.70 |

| K-TMT-E-A | 27.47 | 10.17 | 27.61 | 9.35 | 27.43 | 10.39 | 60.63 | 34.46 | 42.20 | 23.30 | 64.82 | 35.61 |

| K-TMT-E-B | 52.53 | 26.57 | 53.73 | 25.98 | 52.21 | 26.76 | 160.95 | 104.39 | 117.20 | 103.89 | 174.63 | 104.00 |

Abbreviations: CFT, Complex Figure Test; SVVL, Seoul Verbal Learning Test; RCFT, Rey Complex Figure Test; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; K-MMSE, Korean–Mini-Mental State Examination; BNT, Boston Naming Test; SNSB, Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery; SD, standard deviation.

aFull names of abbreviations are reported in “Neuropsychological Assessment” section.

Method of Correlated Vectors and Jensen Effects

The method of correlated vectors (MCV) was devised by Jensen to identify variables that are associated with Spearman’s g, the general factor of mental ability. 3 One should compute the correlation between (a) the vector of the g factor loadings of the subtests of an intelligence test and (b) the vector of the relation of each of those same subtests with the variable in question. So, for instance, an intelligence battery with 4 subtests (A, B, C, and D) is given to monozygotic and dizygotic twins, so that the heritability (h2) of each subtest (A, B, C, and D) can be computed. Let’s say the vector of g loadings is .2, .4, .6, and .8 and the vector of h2 is also .2, .4, .6, and .8, then the g loadings perfectly predict the h2, and we get a perfect correlation between the 2 vectors. Rushton proposed that the term “Jensen effect” be used whenever a clear correlation occurs between g factor loadings and any variable, X. A substantial number of studies have been carried out looking for Jensen effects. 15

Table 1 shows a number of the variables studied, including 12 correlations from studies on the brain, reporting variables such as head size, brain size, and various activities of the brain, and all of them show Jensen effects. We note that all the studies are on normal, healthy persons. Ten correlations, including 1 from a meta-analysis are on genetic effects, with the variables inbreeding, hybrid vigor, and heritability. Older studies show strong positive correlations and a recent meta-analysis of Japanese studies on heritability shows a substantial mean effect as well as 2 recent smaller studies which show negative correlations; so most studies on genetic effects show Jensen effects. The majority of studies which include biological variables show a strong positive correlation with g loadings and are therefore Jensen effects, and this means that there are correlations of biological variables with individual tests of an IQ battery, but by far the most important relationship is with the g factor. There is no complex pattern of relationships, but a very simple one, and that is that the effects are very strongly a function of g and much less so a function of broad or narrow abilities.

Table 1.

Various Studies on the Correlation Between a g Vector and a Second Vector.a

| Study | Variable | r | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jensen 16 | Head size | 0.64 | 286 |

| Wickett et al 17 | Brain volume | 0.65 | 80 |

| Schoenemann 18 | Brain volume | 0.51 | 72 |

| Brain’s cortical gray matter | 0.66 | 72 | |

| Schafer 19 | Brain’s evoked potential habituation index | 0.77 | 52 |

| Eysenck and Barrett 20 | Brain’s averaged evoked potential | 0.95 | 219 |

| Haier et al 21 | Brain’s glucose metabolic rate | 0.79 | 8 |

| Vernon and Mori 22 , Vernon 23 | Peripheral nerve conduction velocity | 0.44 | 85 |

| Rae et al 24 | Intercellular brain pH | 0.63 | 42 |

| Colom et al 25 | Brain gray matter | 0.82 | 23 |

| Brain gray matter | 0.36 | 25 | |

| Lee et al 26 | Brain activity | 0.61 | 36 |

| Schull and Neel 27 | Inbreeding | 0.79 | 865 |

| Badarudozza and Afzal 28 | Inbreeding | 0.83 | 50 |

| Nagoshi and Johnson 29 | Hybrid vigor | 0.52 | 2096 |

| Block 30 | Heritability | 0.62 | 240 |

| Tambs et al 31 | Heritability | 0.55 | 160 |

| Pedersen et al 32 | Heritability | 0.77 | 604 |

| Rijsdijk et al 33 | Heritability | 0.43 | 388 |

| teNijenhuis et al 34 | Heritability | 0.42 | 1808 |

| Voronin et al 35 | Heritability | −0.45 −0.60 |

402 296 |

| Choi et al 36 | Heritability | −0.11 | 88 |

aValue in bold is based upon meta-analyses.

Exploring the Connection Between APOE Carriership and Neurocognitive Scores Using MCV

Alzheimer is a brain disease and carriers of the APOE ε4 allele show an increased risk of manifesting the symptoms, so there is a genetic component involved. Almost all genetic studies of intelligence and all studies linking brain variables to intelligence have been shown to be Jensen effects. In this article, we explore the relationship between the APOE allele and g, and we set out to determine whether this represents a Jensen effect, so we are looking whether Jensen effects generalize from healthy persons to older adults at risk for Alzheimer.

The findings in the literature clearly show that certain neuropsychological tests have strong correlations with the total score on a broad IQ battery, which means they have high g loadings; other neuropsychological tests have weak correlations with the total score on a broad IQ battery, which means they have low g loadings. 9 -13 As neuropsychological tests show a substantial variability in g loadings, it allows us to apply the MCV to neuropsychological test batteries. In this manner, we can test whether neuropsychological tests with lower g loadings show smaller differences between APOE carriers and non-APOE carriers and also test whether neuropsychological tests with higher g loadings show larger differences between APOE carriers and non-APOE carriers, leading to a substantial positive correlation between (1) score differences between carriers and noncarriers on neurocognitive tests and (2) g loadings of these same tests.

One can distinguish between various forms of the Jensen effect3(p372). The strong form of the Jensen effect means that the differences in the effect size are solely due to the differences in g, and it results in a perfect, positive correlation; the weak form of the Jensen effect means that the differences in the effect size are mainly due to differences in g, and it results in a strong, positive correlation. A contra-Jensen effect means that the differences in the effect sizes reside entirely or mainly on the narrow and broad abilities, while the g factor contributes little or nothing to the differences; it results in a small, positive correlation close to zero or even a negative correlation.

Interpretations of Possible Outcomes

All outcomes of the present study are of interest. Finding a clear-cut strong Jensen effect means that we can radically simplify the neurocognitive assessment in Alzheimer research and strongly rely on neuro-g-scores instead of interpreting a large number of scores on individual tests. Aggregated scores more clearly make manifest the underlying relationships, when it is present, 37 ,38 by increasing the strength of a true statistical association between the presence or absence of biomarkers and ratings of cognition. Finding support for the weak form of the Jensen effect would also be informative because a somewhat less powerful neuro-g-score would likely still be a much more powerful measure than scores on a large number of individual neurocognitive tests. Moreover, a scatter plot with a regression of effect sizes (score differences between carriers and noncarriers) on g loadings would supply an easy-to-interpret visualization of which neurocognitive domains are fundamentally linked to g and which neurocognitive domains are the outliers in an assessment of the neurocognition of people at risk for AD. Finally, finding a clear contra-Jensen effect would mean that being an APOE carrier is linked not to g but to specific cognitive domains, strengthening the traditional use of neuropsychological tests, focusing on specific cognitive domains measured by a large number of tests. It would mean that the differences between carriers and noncarriers in Alzheimer research are fundamentally multidimensional and require the assessment of various domains for a proper diagnosis.

Research Questions

We explore whether g loadings of neurocognitive test predict differences between APOE carriers and non-APOE carriers on these same tests for a cognitively normal sample and a sample with AD.

Methods

We used the MCV on a database of Korean older adults at risk for AD to explore the relationship between APOE genotype and scores on a neuropsychological test battery. First, we computed the differences on neurocognitive tests between APOE carriers and non-APOE carriers (group differences). Second, we estimated how strongly the various neurocognitive tests were similar to the g factor of intelligence (g loadings). Finally, we tested whether the g loadings could predict the group differences.

Participants

The National Research Center for Dementia in Gwangju, Korea, established a database with a large amount of information on N = 485 Korean older adults. The institutional review board of Chosun University approved this study. All volunteers signed written informed consent before participation.

In this study, 414 cognitively normal individuals (161 men, 253 women, mean age = 72.74, 70 ε4+, 290 ε4−, and 54 APOE carriership unknown; see “Determination of APOE Genotype” section) and 44 patients with AD (23 men, 21 women, mean age = 75.16, 6 ε4+, 24 ε4−, and 14 APOE carriership unknown) were included in this study. We combined a large sample with a modest size sample, so the combined N is large. For the analyses where only the cognitive data were used, we included the data on 117 patients who took the neuropsychological test battery, but that were not categorized regarding APOE carriership.

The diagnosis of AD was made using the probable AD criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association. 39 The cognitively normal group in this study had a clinical dementia rating (CDR) of 0, and they had no neurological disease and no impairment in cognitive function or activities of daily living. All participants are ethnic Koreans.

Assessment of Dementia

The older adults were rated as belonging to 1 of the 2 groups: neurologically healthy (normal) or AD, by 5 experienced neurologists working at university hospitals in Gwangju, Korea.

Determination of APOE Genotype

Genomic DNA was extracted from buffy coats isolated from whole blood collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes. After the whole-blood samples were centrifuged at 2000 rpm (1500g) for 10 minutes, the plasma was removed, and the buffy coats were saved for DNA extraction. Two hundred nanograms of genomic DNA were used for genotyping through Taqman assays. The APOE genotypes were determined by the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of rs429358 and rs7412.

The APOE genotype information was simplified to a binary classification based on the absence or presence of at least 1 ε4 allele, in accordance with the literature. So, participants with 1 or 2 copies of the ε4 allele (ie, ε3/ε4, ε2/ε4, and ε4/ε4) were considered ε4+; all others were considered ε4−. A second classification based on 3 groups (categorized based on the presence of, respectively, 2, 1, or 0 ε4 alleles) was not possible due to the very small number of participants with ε4/ε4 (n = 2).

Neuropsychological Assessment

All participants underwent comprehensive neuropsychological testing using a standardized battery called the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery, second edition (SNSB) in 2014 and 2015. 40 This battery assesses 5 cognitive domains using 16 tests: attention, memory, language, visuospatial function, and frontal/executive function.

Attention was assessed by Digit Span Forward and Digit Span Backward. Language and related functions were assessed by the Boston Naming Test (BNT). Visuospatial function was assessed by the Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT): copy. Memory was assessed by the Seoul Verbal Learning Test (SVLT): free recall/delayed recall/recognition, and by the Rey Complex Figure Test: immediate recall/delayed recall/recognition. Frontal/executive function was assessed by the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT): Semantic (Animal), the Korean–Color Word Stroop Test (K-CWST): word reading, the Korean–Color Word Stroop Test (K-CWST): color reading, the Korean–Trail Making Test–Elderly’s version (K-TMT-E): A Time, and the Korean-Trail Making Test-Elderly’s version (K-TMT-E): B Time. Digit Symbol Coding was not taken by all participants, so it was not used for the present analyses.

The SNSB also includes the Korean–Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE), the Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL), and CDR, but in the present study, we used only the K-MMSE because it is a performance-based test; and in classical IQ batteries, all tests are performance-based tests and not self-ratings or other-ratings.

Statistical Analyses

The 2 groups were subsequently split into carriers of the APOE allele (APOE ∊4+) and noncarriers of the APOE allele (APOE ∊4−). This led to 2 comparisons: normal APOE ∊4+ versus normal APOE ∊4−, and AD APOE ∊4+ versus AD APOE ∊4−. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

Computing g loadings

The scales of the tests differ substantially; hence, the raw scores were transformed into z scores for all tests using the standard deviations (SDs) of the total research sample. The shape of the distributions for the normal group and the AD group was quite comparable for the large majority of tests.

The tests were keyed as is common in IQ tests: More problems solved correctly is better than fewer problems solved correctly, so a higher score is always better than a lower score.

The K-TMT-E score is the time in seconds spent to complete the test within the limit of 300 seconds. Jahng et al reported that in their study, the K-TMT-E score was distributed with high negative skewness, so they used a log-transformed score. 14 However, we used a z score which led to a distribution of the K-TMT-E score that was similar to those of the other test scores.

When performing a factor analysis on cognitive tests, it is important to have a collection of tests that is more or less evenly distributed over various cognitive domains. This was clearly not the case with many more tests in both the memory domain and the frontal/executive-functions domain. We therefore computed 4 aggregated scores, in all cases starting with z scores. The SVLT aggregate score was computed by summing the scores on SVLT Immediate Recall, SVLT Delayed Recall, and SVLT Recognition. The RCFT aggregate score was computed by summing the scores on RCFT Immediate Recall, RCFT Delayed Recall, and RCFT Recognition. The Stroop aggregate score was computed by summing StroopWordreading Time and StroopColorreading Time. The K-TMT-E aggregate score was computed by summing the scores on K-TMT-E-A and K-TMT-E-B. Aggregating scores has the added benefit of bringing out the underlying relationships more clearly. 37 Second, we analyzed this collection of 10 scores.

We entered the 10 scores in a principal axis factor analysis with no rotation. 3,4 The loadings of the tests on the first, general factor were the g loadings, with a high g loading meaning that it strongly measures the general factor of intelligence and a low g loading meaning that it measures much less strongly the general factor of intelligence. To obtain the optimal range of test scores for this analysis, we used the data of all groups.

Computing differences between APOE carriers and noncarriers on a neurocognitive test

APOE ∊4− was dummy coded as “0” and APOE ∊4+ was dummy coded as “1.” Jensen 3 devised the MCV in such a way that a higher score means a better score and that the scores of the lower scoring group are subtracted from the scores of the higher scoring group, creating generally positive difference scores (d). As, unexpectedly, the APOE carriers had higher scores than the non-APOE carriers, the standardized difference score (d) could be computed by subtracting the raw scores on the tests of APOE ε4− (lower scores) from those of APOE ε4+ (higher scores) and dividing the result by the SD of the whole group. However, there is an easier computation because d is equivalent to rAPOE × SNSB subtests: the correlations of APOE genotype with scores on the neuropsychological tests. For this, we used a point-biserial correlation (rpb) because APOE carriership is a dichotomous variable and the scores on the SNSB tests are generally approximately normally distributed. The rpb is interchangeable with the Pearson r. So, a positive correlation means that APOE carriers have a higher mean cognitive score and non-APOE carriers have a lower mean cognitive score, and a negative correlation means that APOE carriers have a lower mean cognitive score and non-APOE carriers have a higher mean cognitive score.

Table 2 shows some simulated data, illustrating the principle with 4 SNSB tests. It shows the SNSB-g-loadings, with test A having a low g loading and test D having a high g loading; so, test A measures general intelligence to a limited degree and test D measures general intelligence quite strongly. It also shows the difference between the E4+ and the E4− groups. On test A, the scores of carriers and noncarriers differ only .20 SD; this means that group membership (being carrier or being a noncarrier) has only a correlation of r = .10 with the scores on test A. On test D, the scores of carriers and noncarriers differ no less than .80 SD; this means that group membership (being carrier or being a noncarrier) has a strong correlation with the scores on test D.

Table 2.

A Hypothetical Illustration of a Perfect Jensen Effect for 4 SNSB Tests.

| Test | SNSB g Loadings | D | r | Size of Group Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.20 | 0.20 SD | 0.10 | Very small group differences |

| B | 0.40 | 0.40 SD | 0.20 | Small group differences |

| C | 0.60 | 0.60 SD | 0.29 | Large group differences |

| D | 0.80 | 0.80 SD | 0.37 | Very large group differences |

| r (g × d) = 1 | ||||

Abbreviations: SNSB, Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery; SD, standard deviation.

In this example, there is a perfect correlation between g and d. This means that low-g tests do not distinguish well between APOE carriers and non-APOE carriers and that high-g tests do a much better job distinguishing between APOE carriers and non-APOE carriers. In this example, it can be concluded that differences between groups are very strongly a function of the g-loadedness of the SNSB tests.

Method of correlated vectors

We used MCV to correlate (1) the g loadings of the tests of the neuropsychological test battery (g) with (2) the correlations of APOE genotype with the scores on the neuropsychological tests rAPOE × SNSB subtests, so r (g × rAPOE × SNSB subtests). So, we test whether the g loadings of tests predict the strength of the relationship between APOE genotype and cognitive scores, or in other words, whether the relationship of APOE genotype to cognitive scores is simply a function of g. Another way to conceptualize it is to test whether the SNSB tests that show the largest differences (d) between APOE ε4+ and APOE ε4− have the highest g loadings and whether the SNSB tests that show the smallest differences between APOE ε4+ and APOE ε4− have the lowest g loadings, and hence whether differences between the APOE groups on the tests of the SNSB are a function of the g-loadedness of these SNSB tests.

Results

Neuropsychological Assessment

Table 3 reports the means and the SDs of the raw scores for the 2 groups on 16 subtests of the SNSB. It is clear that the normal group has the highest scores and the AD group has the lowest scores. As already mentioned, surprisingly, in both comparisons, the carriers actually generally have better neurocognition. However, it is still possible to analyze the pattern in the data using MCV.

g Loadings

We performed a principal axis factor analysis without rotation on 6 tests and 4 aggregate scores, and the first, unrotated factor explained a substantial amount of variance, namely, 48.1%, which is a clear indication of a general factor similar to the g factor of an IQ battery. Table 4 reports the g loadings for the 10 variables, and they run from a high of .82 to a more modest .56, so there is quite a range of values.

Table 4.

g Loadings and r (APOE carrier × Test) for 6 Tests and 4 Aggregate Scores for Cognitively Normal and AD and Their Correlations.a

| g Loading | r (APOE carrier × test) 1-2 E4 vs 0 E4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | All Tests | Normal | AD |

| Digit Span Forward | 0.56 | −0.015 | 0.043 |

| Digit Span Backward | 0.58 | −0.052 | −0.230 |

| Rey CFT Copy score | 0.76 | 0.112 | 0.032 |

| SVLT Aggregate | 0.58 | 0.054 | 0.041 |

| RCFT Aggregate | 0.71 | 0.023 | 0.207 |

| COWAT Animal | 0.62 | −0.031 | 0.208 |

| Stroop Aggregate | 0.76 | 0.030 | 0.450 |

| K-MMSE | 0.82 | −0.027 | 0.104 |

| Naming (BNT) | 0.77 | 0.012 | 0.294 |

| K-TMT-E-Aggregate | 0.71 | 0.005 | 0.248 |

| Correlation | 0.31 | 0.54 | |

Abbreviations: CFT, Complex Figure Test; SVVL, Seoul Verbal Learning Test; RCFT, Rey Complex Figure Test; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; K-MMSE, Korean–Mini-Mental State Examination; BNT, Boston Naming Test.

aFull names and abbreviations are reported in text.

Correlation Between APOE Alleles and SNSB Test Scores

The correlations of APOE genotype with scores on the neuropsychological tests rAPOE × SNSB subtests are reported in Table 4. A positive correlation means that APOE carriers have a higher mean cognitive score and non-APOE carriers have a lower mean cognitive score, and a negative correlation means that APOE carriers have a lower mean cognitive score and non-APOE carriers have a higher mean cognitive score. The majority of the correlations is positive and small.

Method of Correlated Vectors

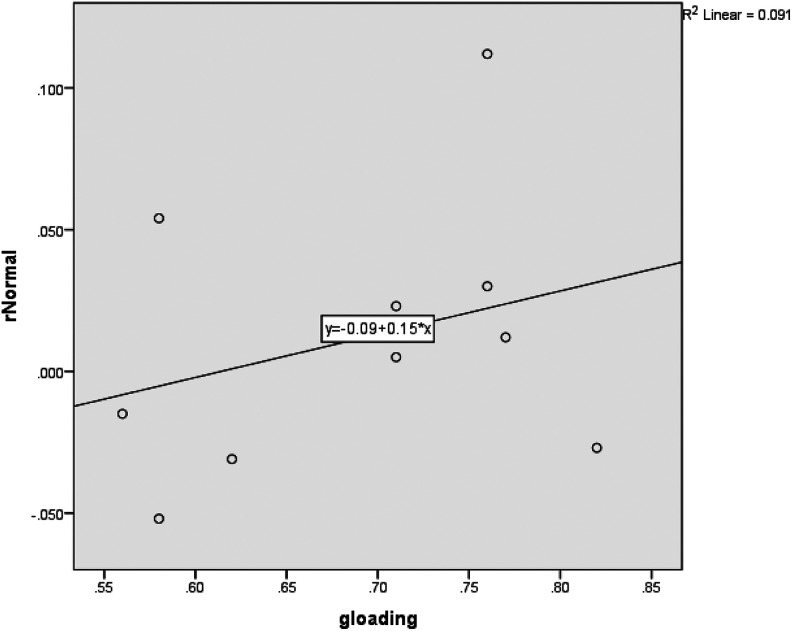

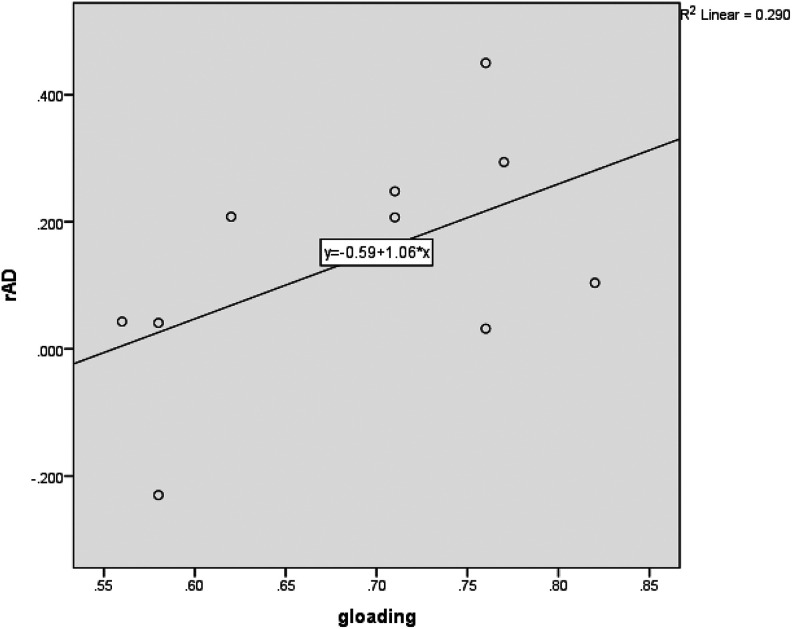

Table 4 reports the correlation between (1) the g loadings of the tests of the neuropsychological test battery (g) and (2) the correlations of APOE genotype with the scores on the neuropsychological tests rAPOE × SNSB subtests, so r (g × rAPOE × SNSB subtests). There is a clear positive correlation for the normal group and a quite strong positive correlation for the AD group. Figures 1 and 2 show the scatter plot with g loadings on the x-axis and the correlations on the y-axis, plus the regression line, for the 2 different groups.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of g loadings (x-axis) by differences on tests between carriers and noncarriers expressed as a correlation with carriership (y-axis) and regression line for 6 tests and 4 aggregated scores for normal group; the dots express the tests.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of g loadings (x-axis) by differences on tests between carriers and noncarriers expressed as a correlation with carriership (y-axis) and regression line for 6 tests and 4 aggregated scores for AD group; the dots express the tests. AD indicates Alzheimer’s disease.

In sum, we test whether g loadings of tests predict the strength of the relationship between APOE genotype and cognitive scores; in other words, whether the relationship of APOE genotype to cognitive scores is simply a function of g. Another way to conceptualize it is to test whether the SNSB subtests that show the largest differences (d) between APOE ε4+ and APOE ε4− have the highest g loadings and whether the SNSB tests that show the smallest differences between APOE ε4+ and APOE ε4− have the lowest g loadings, and as a result whether differences between the APOE groups are a function of g loadings. The outcomes show that for patients with AD, the scores on the SNSB are much less complex than previously thought: The scores are very strongly a function of g. To a lesser degree, this is the case for the normal group.

Discussion

We used the MCV on a database of Korean older adults at risk for AD to explore whether the relationship between APOE genotype and the scores on a neuropsychological test battery is a function of how well the tests measure general intelligence. We find that there is a clear Jensen effect for the AD group and a relatively clear Jensen effect for the cognitively normal group. So, findings of Jensen effects appear to generalize from healthy persons to older adults at risk for Alzheimer and actual Alzheimer patients.

Why Is This an Important Finding?

Why is this an important finding for Alzheimer research? At the moment, there is confusion in the literature: zero or even negative differences between carriers and noncarriers on one neurocognitive test, larger differences between carriers and noncarriers on a second neurocognitive test, and even larger differences between carriers and noncarriers on yet a third neurocognitive test. We showed that, at least for AD, there is clearly much less confusion than previously thought. A test showing very small differences between carriers and noncarriers most likely has low g loadings, and a test showing the largest group differences most likely has high g loadings. There is a dimension underlying these group differences, and it is one of g loadedness. The confusion in the neurocognitive literature can be reduced by taking the dimension of similarity to a perfect IQ test into account. However, the pattern is less strongly found for the healthy older adults.

Composite Scores

Genomic studies have been carried out to predict the onset of AD. For the SNSB, it means correlating the scores on 16 different tests with SNPs. However, aggregating the scores on the 16 tests by computing a composite score would yield a measure of what one could call neuro-g, as an indication of the general health of the brain. The classical laws of statistics tell us that variables with low reliability yield much lower correlations than variables with high reliability: Low reliability attenuates the correlations. So, if there is an SNP that is predictive of Alzheimer, our analyses suggest that a composite score in certain cases will indicate the relationship more clearly than 16 different individual test. By implication, if there are true associations in certain cases, then the composite score will provide a more robust measure of identifying these associations as opposed to 16 individual tests.

Observed Effects Strongly Underestimate True Effects

It is crucial to know that the correlations reported here substantially underestimate the true effects. The MCV has the advantage in that it can be relatively easily applied to various data sets, but it is also strongly influenced by various measurement artifacts, such as reliability of the g vector and the d vector and restriction of range in the g loadings in the g vector, which quite strongly weaken the observed correlation. 3 These effects of measurement error are taken into account in sophisticated and popular meta-analysis programs. 38 Various recent meta-analyses 41,42 have shown that in a meta-analysis based on many data points, the distribution of the values of these statistical artifacts can be quite accurately computed. The observed correlations can then be corrected for measurement error quite accurately, leading to a value which is much closer to the true value of the correlation. The cited meta-analyses show that these corrections often lead to corrections of approximately 30%, which means that the observed values in the present study require strong corrections. In fact, as there is quite severe restriction of range in the g loadings in the present study, the corrections required here should be even stronger and, as such, our figures are conservative.

Limitations

Our finding of better neurocognition for APOE carriers is unusual, so we need to apply the same techniques to an independent data set. However, the unusual scores could still be analyzed using MCV and in both cases showed Jensen effects. Other SNPs should also be tested for Jensen effects.

The g score of the 16-test SNSB is not perfect because there are a number of memory tests which obscure the findings somewhat, so the g score based on all 16 subtests has quite a memory flavor.3 However, we used aggregate scores, so the 5 domains were more evenly contributing to the g score. A more optimal way to estimate the g-loadedness of the tests would be to correlate all tests with the total score or the g score of a traditional intelligence battery, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale or the Raven’s Progressive Matrices total score. This could be carried out in future research. Also, although most neurocognitive test batteries show clear similarities, replication studies on other test batteries need to be carried out. Finally, it is possible that the Korean older adults in our study show a group-specific cognitive pattern, so replications on other racial groups are necessary.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2014M3C7A1046041) and by the Research Fund from Chosun University.

Authors’ Note: Dr. Lee can be contacted for reprint requests.

Author Contribution: Jan teNijenhuis, PhD, and KyuYeong Choi, PhD, contributed equally.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The funding sources were not involved in the research process, the preparation of the article, the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

ORCID iD: Jan te Nijenhuis  http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1268-6121

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1268-6121

References

- 1. Selkoe DJ. Preventing Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2012;337(6101):1488–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spearman C. “General intelligence,” objectively determined and measured. Am J Psychol. 1904;15(2):201–292. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jensen AR. The g Factor: The Science of Mental Ability. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1998. Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jensen AR, Weng LJ. What is a good g? Intelligence. 1994;18:231–258. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson W, Bouchard TJ, Jr. Constructive replication of the visual–perceptual-image rotation model in Thurstone’s (1941) battery of 60 tests of mental ability. Intelligence. 2005;33(4):417–430. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson W, Bouchard TJ., Jr The structure of human intelligence: it is verbal, perceptual, and image rotation (VPR), not fluid and crystallized. Intelligence. 2005;33:393–416. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson W, Nijenhuis JT, Bouchard TJ, Jr. Still just 1 g: consistent results from five test batteries. Intelligence. 2008;36(1):81–95. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carroll JB. Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-Analytic Studies. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diaz-Asper CM, Schretlen DJ, Pearlson GD. How well does IQ predict neuropsychological test performance in normal adults? J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(1):82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dodrill CB. Myths of neuropsychology. Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;11(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dodrill CB. Myths of neuropsychology: further considerations. Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;13(4):562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tremont G, Hoffman RG, Scott JG, Adams RL. Effect of intellectual level on neuropsychological test performance: a response to Dodrill (1997). Clin Neuropsychol 1998;12(4):560–567. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Warner MH, Ernst J, Townes BD, Peel J, Preston M. Relationships between IQ and neuropsychological measures in neuropsychiatric populations: within-laboratory and cross-cultural replications using WAIS and WAIS-R. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1987;9(5):545–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jahng S, Na DL, Kang Y. Constructing a composite score for the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery-Core. Dement Neurocognitive Disord. 2015;14(4):137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rushton JP. The “Jensen Effect” and the “Spearman-Jensen hypothesis” of Black-White IQ differences. Intelligence. 1998;26(3):217–225. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jensen AR. Psychometric g related to differences in head size. Personal Individ Differenc 1994;17(5):597–606. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wickett JC, Vernon PA, Lee DH. In vivo brain size, head perimeter, and intelligence in a sample of healthy adult females. Personal Individ Differ. 1994;16(6):831–838. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schoenemann PT. An MRI Study of the Relationship Between Human Neuroanatomy and Behavioral Ability. Berkeley, CA: University of California; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schafer EWP. Neural adaptability: a biological determinant of g factor intelligence. Behav Brain Sci. 1985;8:240–241. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eysenck HJ, Barrett P. Psychophysiology and the measurement of intelligence. In: Reynolds CR, Willson VL, eds. Methodological and Statistical Advances in the Study of Individual Differences. Boston, MA: Springer; 1985:1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haier RJ, Siegel B, Tang C, Abel L, Buchsbaum MS. Intelligence and changes in regional cerebral glucose metabolic rate following learning. Intelligence. 1992;16(3-4):415–426. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vernon PA. Intelligence and Neural Efficiency: Individual Differences and Cognition. Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing; 1993:171–187. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vernon PA, Mori M. Intelligence, reaction times, and peripheral nerve conduction velocity. Intelligence. 1992;16:273–288. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rae C, Scott RB, Thompson CH, et al. Is pH a biochemical marker of IQ? Proc Biol Sci. 1996;263(1373):1061–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Colom R, Jung RE, Haier RJ. Distributed brain sites for the g-factor of intelligence. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):1359–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee KH, Choi YY, Gray JR, et al. Neural correlates of superior intelligence: stronger recruitment of posterior parietal cortex. Neuroimage. 2006;29(2):578–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schull WJ, Neel JVG. The Effects of Inbreeding on Japanese Children. New York: Harper & Row; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Badaruddoza, Afzal M. Inbreeding depression and intelligence quotient among North Indian children. Behav Genet. 1993;23(4):343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagoshi CT, Johnson RC. The ubiquity of g. Personal Individ Differ 1986;7:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Block JB. Hereditary components in the performance of twins on the WAIS. In: Vandenberg SG, ed. Progress in Human Behavior Genetics Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1968:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tambs K, Sundet JM, Magnus P. Heritability analysis of the WAIS subtests. A study of twins. Intelligence. 1984;8:283–293. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedersen NL, Plomin R, Nesselroade JR, McClearn GE. A quantitative genetic analysis of cognitive abilities during the second half of the life span. Psychol Sci. 1992;3:346–353. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rijsdijk FV, Vernon PA, Boomsma DI. Application of hierarchical genetic models to raven and WAIS subtests: a Dutch twin study. Behav Genet. 2002;32(3):199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. te Nijenhuis J, Kura K, Hur YM. The correlation between g loadings and heritability in Japan: a meta-analysis. Intelligence. 2014;46:275–282. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Voronin I, te Nijenhuis J, Malykh SB. The correlation between g loadings and heritability in Russia. J Biosoc Sci. 2016;48(6):833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Choi YY, Cho SH, Lee KH. No clear link between g loadings and heritability: a twin study from Korea. Psychol Rep. 2015;117(1):291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rushton JP, Brainerd CJ, Pressley M. Behavioral development and construct validity: the principle of aggregation. Psychol Bull. 1983;94(1):18. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmidt FL, Hunter JE. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings. Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kang Y, Na D, Hahn S. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery. Incheon: Human Brain Research & Consulting Co; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41. te Nijenhuis J, van der Flier H. Is the Flynn effect on g? a meta-analysis. Intelligence. 2013;41(6):802–807. [Google Scholar]

- 42. te Nijenhuis J, van Vianen AEM, van der Flier H. Score gains on g-loaded tests: no g. Intelligence. 2007;35:283–300. [Google Scholar]