Abstract

Based on stress coping theory, this study investigated whether and how positive aspects of caregiving (PAC) and religiosity buffered the association between caregiving burden and desire to institutionalize (DTI). Secondary data (N = 637) were drawn from the baseline assessment of the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health II project. Descriptive analysis, bivariate correlation, and multiple linear regressions were conducted. The results indicated that higher levels of caregiver burden, daily care bother, and Revised Memory and Behavioral Problem Checklist bother were all significantly associated with higher level of DTI. Both PAC and religious coping were negatively associated with DTI; however, only PAC was significant. Only the interaction between daily care bother and religious coping was significant, which indicated that the harmful effect of daily care bother on DTI was significantly buffered among those who have religiosity. Study findings have important implications for policy makers and for providers who serve dementia family caregivers.

Keywords: caregiving burden, desire to institutionalize, positive aspects of caregiving, religiosity

Introduction

According to the National Alzheimer’s Association, 1 Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementia (ADRD) is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and is expected to triple in prevalence over the next 30 years. Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementia is characterized by significant disability, loss of independence, and skyrocketing health-care costs. 2 Family caregivers (CGs) provide the majority of care and support for persons with ADRD. 3 In 2015, more than 15 million family CG provided approximately 18.1 billion hours of unpaid assistance and 21.9 hours of care per week to persons with ADRD. 1

Studies indicate that the CGs of persons with ADRD have high and persistent rates of CG burden. 4 Studies suggest that CG burden is heightened with the increased need for assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) of persons with ADRD. 5 Many CGs for persons with ADRD experience “daily care bother” as a result of providing assistance with ADLs. 6–7 Daily care bother is the distress that the CG experiences in helping the care recipient (CR) with ADL tasks such as bathing, eating, or shopping. 8 The severity of behavioral problems for the CR is also associated with higher CG burden. 9 Behavioral problems of the CR may include various challenges related to depression (eg, crying, suicidal threats), disruption (eg, verbal and/or physical aggression), and memory (eg, losing items, hiding things). 10

Although the majority of ADRD caregiving in the United States is provided by family members, nursing homes and other institutional settings may provide long-term care for persons with ADRD when living at home is no longer an option. However, institutional care is often cost prohibitive for many families and/or is often considered an undesirable outcome for persons with ADRD. Greater understanding of the factors influencing CG desire to institutionalize (DTI) CR is an important topic given the predicted future growth in the numbers of ADRD family CGs and may shed light on potential interventions to delay or prevent institutional care.

The desire for institutional care (eg, contemplating and/or planning for institutional placement which includes nursing homes, boarding homes, or assisted living) has been found to be a reliable measure for assessing future nursing home admissions among White, African American, and Hispanic dementia CGs. 11 Research suggests that the stress of dementia caregiving for family CGs is a predictor of institutionalization such as nursing home placement. 12 In particular, research has shown that persistent memory problems and other behavioral disturbances are strong predictors of the time to a nursing home placement. 13 Research has also found that CG burden and depression are associated with the DTI persons with dementia. 14

What remains unknown about DTI are other aspects of ADRD caregiving, including coping mechanisms for CG. Previous research suggests that both positive aspects of caregiving (PAC) 15 and religious coping 16 are associated with positive CG outcomes; however, scant research examines their relationship with DTI. Caregivers who report feeling appreciated and useful in their caregiving roles may better cope with CG stress/burden and in turn may be less likely to institutionalize the CR. Similarly, CGs who seek spiritual connections and feel in collaboration with a higher power in problem-solving caregiving stress/burden may be more likely to care for the CR at home.

The purpose of this study is to examine the association between caregiving burden and the CG DTI, while investigating the roles of PAC and religious coping of CG in such association. This study is important as previous research has identified coping strategies, including religious coping and positive reframing, as potentially modifiable CG attributes associated with CG DTI. 17 Thus, study findings may help us to better understand PAC and religious coping as potentially modifiable factors and may offer insight into the design of psychosocial interventions to support CG caring for their loved ones at home rather than in institutional settings.

Theoretical Model

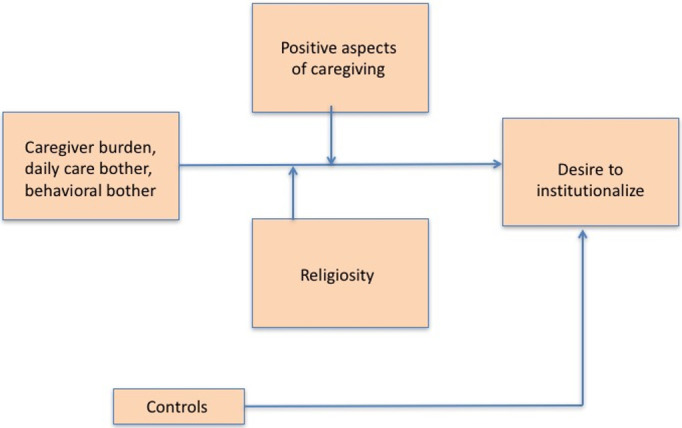

The stress process model (SPM) 18 was used as a conceptual framework for analyzing the role of PAC and religious coping as an influence on CG DTI. The SPM 18 suggests that CG stress is the result of a process that includes the key characteristics of the CG (eg, background and context) and primary and secondary stressors that are related to caregiving hardships. According the the model, social support and coping may also serve as protective factors in the stress process. 18 Previous research has utilized constructs mentioned in the Pearlin SPM to examine predictors of institutionalization 17,19 as well as mechanisms influencing DTI. 20 In the model for this study, the PAC and religious coping are viewed as a resource for CG to reduce stress thereby reducing DTI (see Figure 1). Understanding the role of PAC and religious coping for CG may result in deeper knowledge of the needs of ADRD caregiving.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

PAC as a potential coping resource

The PAC has been defined as a CG feeling that his or her caregiving experience is, in general, satisfying and rewarding. 15 Positive aspects of caregiving may include gains such as CG satisfaction, emotional rewards, personal growth, competence, and spiritual growth as well as benefits in the overall CG-CR relationship. 21 Kinney and Stephens suggested that PAC reduced CG stress as CGs attempt to find satisfaction in their caregiving role. 22

A longitudinal study of the effects of PAC on caregiving indicated that CGs with positive appraisals of their caregiving role reported lower rates of depression, reduced bother related to CR behavioral problems, and lower CG burden related to the daily care tasks. 7 Basu et al found that positive improvements in the CG experience as measured by high scores on the PAC scale were associated with enhanced self-reported health status. 23 Overall, more research is needed to examine PAC and DTI as only 1 previous study found that CGs who reported greater PAC were less likely to institutionalize CR with ADRD 24 , specifically how PAC moderated the association between caregiving burden and DTI.

Religiosity as a potential coping resource

Family CGs may turn to religion or spirituality to cope with their caregiving role. Religious coping is “designed to assist people for a variety of significant ends in stressful times: a sense of meaning and purpose, emotional comfort, personal control, intimacy with others, physical health, or spirituality.” 25 Research suggests that there is a positive relationship between religious and/or spiritual support with health behavior patterns among family CG, particularly for dementia CG. 26 Involvement in religious activities (eg, church attendance) has been associated with lower perceived burden among dementia CG, 27 and greater levels of religious coping were associated with lower levels of CG depression. 28 Heo and Koeske indicated that religion represents an accessible resource for CGs in terms of increasing their stress tolerance as it relates to the caregiving role. 29 Using data from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health II (REACH II) study, Heo found that religious coping is a psychosocial resource that allows CGs to positively reframe their role as CGs and that positive religious coping was associated with CG social support. 30 Given that previous research suggests that religious coping may be an important resource for ADRD CG, a closer examination of its buffering effect on the association between caregiving burden with DTI is warranted.

Based on the stress-coping model, this study extends the literature by examining the moderating/coping roles of PAC and religiosity in the association between caregiving burden and DTI. Specifically, this study has the following research questions:

Whether caregiving burdens, specifically CG’s burden, Revised Memory and Behavioral Problem Checklist (RMBPC) bother, and daily care bother, are positively associated with higher DTI?

Based on the previous literature and using the SPM, 18 does PAC or religious coping moderate the relationship between CG burden, daily care bother, RMBPC bother, and DTI?

Methods

Sampling

Secondary data were drawn from the baseline assessment of the REACH II project. Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health II was a 6-month multisite clinical trial that enrolled 670 CG/CR dyads to evaluate a multicomponent psychosocial intervention across 5 sites (ie, Birmingham, Alabama; Memphis, Tennessee; Miami, Florida; Palo Alto, California; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

Caregivers were at least 21 years old, living with or sharing cooking facilities with the CR, providing daily care to a CR for at least 6 months and reporting at least 2 symptoms of distress. 31 The CR had to have a diagnosis of ADRD or a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) 32 score of 23 or lower; however, bedbound CRs with a score of 0 on the MMSE were excluded. The final sample size for the present study was 637 dementia CGs. Baseline data were collected during face-to-face interviews after obtaining informed consent from eligible participants. Further information about the REACH II procedures is described in detail elsewhere. 31

Measurement

Variables included in the study consisted of CG burden (Zarit Burden, daily care bother, behavioral bother), religious coping, positive aspect of caregiving, and the outcome variable, DTI. Previous studies of REACH suggest that all measures had good reliability and validity. 31,33

Dependent variable-DTI. 34 Participants were asked 6 yes/no questions regarding their anticipated plans to institutionalize their CR (eg, “In the past 6 months, have you considered a nursing home, boarding home, or assisted living for [CR]?”; “In the past 6 months, have you taken any steps toward placement?”). This scale has been validated elsewhere across 3 ethnic groups using REACH II data. 11 Results of an exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis reveal that this scale demonstrates consistency across 3 ethnic groups. Congruence coefficients were greater than 0.95 for all comparisons, and α coefficients of .694, .742, and .767 for Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics, respectively, indicate acceptable reliability. 11 Total scores were calculated for final analysis with range of 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating higher DTI. Cronbach α for this sample is .72.

Independent variables—the measures used in this study were the Zarit Burden Inventory, 35 daily care bother, 3 and the RMBPC. 10 Each measure has been validated for use with diverse cultural groups (eg, minority ethnic/racial groups) and is used extensively across caregiving studies. 31

Caregiver burden was measured by the Zarit Burden Inventory. 35 Twelve items of the abbreviated Zarit Caregiver Burden Inventory (ZBI) were rated on a 5-point scale from 0 = never to 4 = nearly always to assess the burden associated with caregiving (eg, not enough time for oneself, not as much privacy, etc). Sum scores were calculated ranging from 0 to 46, with higher scores indicating higher reported burden. Cronbach α for this sample was .86.

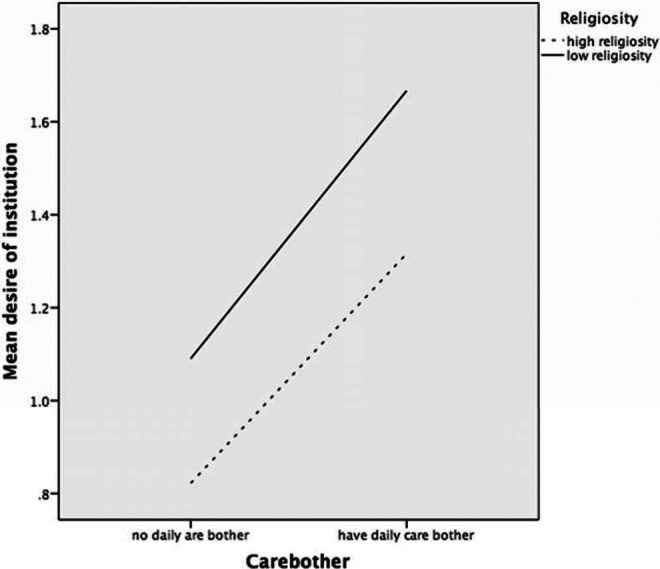

Daily care bother 3 : Bother associated with the tasks of providing daily care or assistance with ADL 36 was computed. For each task of assistance provided, CGs reported their level of upset on a 5-point scale from 0 = no upset to 4 = extremely upset. Sum score of CG bother score was calculated with a range from 0 to 25. Higher scores indicate more care-related upset. Cronbach α for this sample is .93. To better graph the interaction term, the sum scores were recoded dichotomously (0 = no daily care bother, 1-25 = having daily care bother).

Behavioral bother 10 : Behavior bother was measured RMBPC. For each endorsed problem behavior, CGs reported how bothered or upset they were using a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely). This behavior bother score was calculated by summing all the items ranging from 0 to 79, with higher scores indicating greater level of behavioral bother. Cronbach α for this sample is .85.

Moderating variables—positive aspect of caregiving and religious coping was included as moderating variables in this study. Positive experience of caregiving was measured with PAC scale. 15 Using a 5-point scale (0 = disagree a lot to 4 = agree a lot), the 11-item PAC scale presented statements about the CG’s mental or affective state that were designed to assess the perception of benefits within the caregiving context. Similarly, a sum score was calculated with a range of 0 to 44. The Cronbach α for the PAC scale in this sample was .86. This scale’s validity has been reported as “mostly free from major item bias” and as valid and suitable for use assessing for positive experiences across CGs. 37

Religious coping was measured with the short form of the Brief Religious Coping (6 items) to assess the positive and negative aspects of religious coping. 25 All items had a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a great deal). The total score reflects the sum of all 6 items after recoding the positive factor items and ranged from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating higher levels of religious coping. The Cronbach α obtained with this scale in this sample was .72. This instrument has demonstrated strong construct validity among CGs and persons facing life crises. 30,38,39 To better graph its interaction effect with independent variables, the sum scores of religiosity were recoded as low (scores 0-12) and high levels (scores 13-18).

Control variables in this study included some demographics of both CG and CR. Control variables of CGs included age, gender (1= being female), race/ethnicity (Caucasian is the reference group), financial strain, education, self-reported health status, year and hours of caregiving, and number of other members helped. Control variables of CR included age, marital status (1 = being married), functional limitations, whether had many memory problems (1 = yes), whether improved cognitive functions (1 = yes), behavioral functions (1 = yes), and mood functions (1 = yes). Care recipient’s functional limitation was measured by ADLs and Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL)s. Seven ADL items assessed the CRs’ ability to perform basic daily functioning tasks independently (eg, bathing, dressing, toileting). Eight IADL items assessed whether or not assistance was needed to perform higher level tasks such as shopping, cooking, or managing medications. A summed total level of assistance required for ADLs and IADLs was used with higher scores, indicating greater physical functional impairment. The range of possible scores was from 0 to 15.

Analysis Procedure

Bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to address the 3 research questions using SPSS 19.0. We conducted descriptive statistical analysis to describe the demographic backgrounds of all participants and frequencies of key variables. Bivariate correlation analyses were conducted before we ran multiple linear regression models. Multiple linear regressions were then conducted with 3 models. In the first model, demographic variables and the 2 moderating variables (positive aspect of caregiving and religious coping) were put in the model. Then, 3 key independent variables, CG burden, daily care bother, and RMBPC bother, were added into the second model to answer research question 1. In the third model, 6 interactions between positive aspect of caregiving and religious coping with CG burden, daily care bother, and RMBPC bother were added to answer research question 2. All the key independent and moderator variables were mean centered before they were used to compute the interactions. We used listwise deletion to address missing data because of the small percentage of missing data (less than 5%). Before running the regression models, we conducted a multicollinearity test of the independent variables. The results showed that the tolerance values of the independent variables were greater than the common cutoff threshold of 0.1, indicating that multicollinearity was at an acceptable level. 40

Results

Sample Characteristics

The means, standard deviations, and frequencies of the measures used in the multivariate regression models are shown in Table 1. Among the 637 dementia CG participants, the average age for CGs was 60.53 (SD = 13.32), ranging from 23 to 90 years old, and the average years of education for CGs were 12.58 (SD = 3.15). The majority of them were female (83%). The CGs were almost equally divided among 3 ethnic groups with 33% Hispanic, 33% African American, and 34% Caucasian. In terms of financial strain, 26.9% of the CGs found financial matters “not difficult at all” and 73.1% felt that finances were “somewhat difficult,” “difficult,” or “very difficult.” In general, the CGs had a slightly good self-rated health (M = 2.87, SD = 1.07) ranging from 1 to 5. On average, the CGs provided care for 4.87 years (SD = 7.32, range = 1-58) and spent 15.24 hours every day (SD = 7.60, range = 4-24) for the person with dementia. The mean number of other family members helped were 1.87 (SD = 2.46), ranging from 0 to 7. For the CRs, their mean age was 79.05 (SD = 9.15) with a range of 44-100. They had a relatively poor functional health measured by limitations with ADLs and IADLs (M = 10.63, SD = 3.50), ranging from 0 to 15. The majority (77%) of them had many memory problems, and very few of them improved cognitive functions (11.8%), behavioral functions (17%), or mood functions (22.6%).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N = 637).

| Variables | Mean (SD) | % | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| CG’s characteristics | |||

| Age of CG | 60.46 (13.34) | 23-90 | |

| Gender of CG (female) | 82.9 | ||

| CG’s years of education | 12.56 (3.16) | 0-17 | |

| CG’s ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 33.0 | ||

| African American | 33.0 | ||

| Caucasian | 34.0 | ||

| Financial strain of CG | 1.39 (1.01) | 0-3 | |

| Not difficult at all | 26.9 | ||

| Somewhat difficult | 21.1 | ||

| Difficult | 38.3 | ||

| Very difficult | 13.8 | ||

| Self-rated health of CG | 2.87 (1.07) | 1-5 | |

| Poor | 9.4 | ||

| Fair | 29.0 | ||

| Good | 34.1 | ||

| Very good | 19.9 | ||

| Excellent | 7.5 | ||

| Years taken care of CR | 4.87 (7.32) | 1-58 | |

| Hours caring for CR | 4-24 | ||

| Number of other family members helped | 1.87 (2.46) | 0-7 | |

| CR’s characteristics | |||

| Age of CR | 79.05 (9.15) | 44-100 | |

| CR being married | 46.8 | ||

| CR’s functional limitations | 10.63 (3.50) | 0-15 | |

| CR had many memory problems (yes) | 72.2 | ||

| CR improved cognitive functions (yes) | 11.8 | ||

| CR improved behavioral functions (yes) | 17.0 | ||

| CR improved mood functions (yes) | 22.6 | ||

| Key variables | |||

| Caregiver burden | 18.79 (9.85) | 0-46 | |

| Daily care bother | 3.72 (5.30) | 0-25 | |

| RMBPC bother | 16.82 (13.43) | 0-79 | |

| Positive aspect of caregiving | 30.97 (10.90) | 0-44 | |

| Religiosity coping | 14.54 (3.71) | 0-18 | |

| Desire of institution placement | 1.17 (1.49) | 0-6 |

Abbreviations: CG, caregiver; CR, care recipient; RMBPC, Revised Memory and Behavioral Problem Checklist.

For the major variables in this study, the CGs reported an average of overall CG burden of 18.79 (SD = 9.85), ranging from 0 to 46. On average, they also had daily care burden of 3.72 (SD = 5.30) ranging from 0 to 25, and RMBPC burden of 16.82 (SD = 13.43) with a range of 0 to 79. Caregivers reported positive aspects about caregiving with an average PAC score of 30.97 (SD = 10.90) ranging from 0 to 44. They also reported a mean score of religious coping, which was 14.54 (SD = 3.71) with a range of 0 to 18. In general, CGs reported a low DTI with an average score of 1.17 (SD = 1.48) ranging from 0 to 6.

Caregiver Burden, Daily Care Bother, RMBPC Burden, and Desire for Institutional Placement

First, the binary correlations among the key variables are shown in Table 2. Findings indicate that CG burden (r = 0.34), daily care bother (r = 0.28), RMBPC bother (r = 0.22), PAC (r = −0.32), and religious coping (r = −0.15) were significantly correlated with DTI at P < .001 significance level.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Key Variables in This Study.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Caregiver burden | 1 | |||||

| 2 | Daily care bother | 0.56a | 1 | ||||

| 3 | RMBPC bother | 0.38a | 0.36a | 1 | |||

| 4 | Positive aspect of caregiving | −0.42a | −0.26a | −0.17a | 1 | ||

| 5 | Religiosity coping | −0.21a | −0.15a | −0.11b | 0.32a | 1 | |

| 6 | Desire of institution placement | 0.34a | 0.28a | 0.22a | −0.32a | −0.15a | 1 |

Abbreviation: RMBPC, Revised Memory and Behavioral Problem Checklist.

a P < .001.

bp < .01.

Results from multivariate linear regression models on DTI are reported in Table 3. Model 1 included all the control variables and the moderators. The results showed that both PAC and religious coping were negatively associated with DTI; however, only PAC was a significant factor of DTI (β = −.29, P < .001). This suggests that CGs who experienced PAC were significantly less likely to have DTI.

Table 3.

Regression on Desire of Institution Placement (N = 637).

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| CG’s characteristics | |||||||||

| Age of caregiver | −0.01 | 0.01 | −.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −.02 |

| Gender of caregiver (female) | −0.40 | 0.16 | −.10a | −0.42 | 0.15 | −.11b | −0.42 | 0.15 | −.11b |

| Years of education of caregivers | 0.02 | 0.02 | .04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −.01 |

| Being African American | −0.18 | 0.15 | −.06 | −0.07 | 0.15 | −.02 | −0.07 | 0.15 | −.02 |

| Being Hispanic | −0.31 | 0.16 | −.10 | −0.19 | 0.16 | −.06 | −0.20 | 0.16 | −.06 |

| Financial strain of caregivers | −0.04 | 0.14 | −.01 | −0.13 | 0.14 | −.04 | −0.14 | 0.14 | −.04 |

| CG’s self-rated health | −0.05 | 0.06 | −.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | .03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | .03 |

| Years taken care of CR | −0.01 | 0.01 | −.06 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −.07a | −0.02 | 0.01 | −.07a |

| Hours caring for CR | −0.01 | 0.01 | −.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −.04 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −.03 |

| Number of other family members helped | 0.00 | 0.02 | .01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .00 |

| CR’s characteristics | |||||||||

| Age of CR | 0.00 | 0.01 | −.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .00 |

| CR being married | −0.18 | 0.15 | −.06 | −0.13 | 0.15 | −.04 | −0.12 | 0.15 | −.04 |

| CR’s functional limitations | 0.05 | 0.02 | .12b | 0.04 | 0.02 | .08a | 0.03 | 0.02 | .08a |

| CR has memory problems | 0.05 | 0.07 | .03 | 0.00 | 0.07 | .00 | 0.01 | 0.07 | .00 |

| CR improves cognitive functions | 0.28 | 0.20 | .06 | 0.30 | 0.20 | .07 | 0.31 | 0.19 | .07 |

| CR improves behavioral functions | −0.15 | 0.18 | −.04 | −0.10 | 0.18 | −.03 | −0.10 | 0.18 | −.02 |

| CR improves mood functions | 0.11 | 0.15 | .03 | 0.14 | 0.15 | .04 | 0.12 | 0.15 | .03 |

| Positive aspect of caregiving | −0.04 | 0.01 | −.29c | −0.03 | 0.01 | −.22c | −0.03 | 0.01 | −.21c |

| Religiosity coping | −0.01 | 0.02 | −.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .01 |

| Caregiver burden | 0.03 | 0.01 | .17b | 0.03 | 0.01 | .17b | |||

| RMBPC bother | 0.01 | 0.01 | .12a | 0.01 | 0.01 | .12a | |||

| Daily care bother | 0.01 | 0.01 | .05a | 0.01 | 0.01 | .03a | |||

| Positive × caregiver burden | 0.00 | 0.00 | −.04 | ||||||

| Positive × daily care bother | 0.00 | 0.00 | −.01 | ||||||

| Positive × RMBPC bother | 0.01 | 0.00 | .03 | ||||||

| Religion × caregiver burden | 0.00 | 0.00 | .04 | ||||||

| Religion × daily care bother | 0.00 | 0.00 | −.07a | ||||||

| Religion × RMBPC bother | 0.00 | 0.00 | −.05 | ||||||

| Constant | 1.59a | 0.72 | 1.59a | 0.71 | 1.60a | 0.71 | |||

| Adjust R 2 | 0.13 | 0.181 | 0.183 | ||||||

Abbreviations: CG, caregiver; CR, care recipient; RMBPC, Revised Memory and Behavioral Problem Checklist.

a P < .05.

b P < .01.

c P < .001

Model 2 examines the effects of 3 key independent variables of CG burden, daily care bother, and RMBPC bother on DTI after controlling for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. The results indicated that higher levels of CG burden (β = .17, P < .01), daily care bother (β = .12, P < .05), and RMBPC bother (β = .05, P < .05) were significantly associated with higher level of DTI.

Model 3 incorporates 6 interactions between 2 moderators and 3 key independent variables. It tested the moderating effects of PAC or religious coping, investigating whether the deleterious impact of caregiving burden, daily care bother, and RMBPC bother falls differentially on the CG with different levels of PAC or religiosity. As shown in model 3 of Table 3, only the interaction between daily care bother and religious coping was significant (β = −.07, P < .05), and the slopes between low and high levels of religious coping were significantly different from zero (P < .04). These results indicated that the harmful effects of daily care bother on DTI were significantly buffered among those who have high level of religious coping. To better exhibit the moderating effects showed by the interaction, Figure 2 was created. As shown in Figure 2, the interaction effect was very small (magnitude) because the 2 lines in Figure 2 were almost parallel. The model for the total sample accounted for 18.3% of the variability (adjusted R 2 = 0.183) in DTI among CGs.

Figure 2.

Desire of institution placement based on religiosity and daily care bother.

Among the control variables, the results across 3 models consistently showed that CGs who were female (β = −.11, P < .01), who provided care for more years (β = −.07, P < .05), or the CR who had fewer functional limitations (β = −.08, P < .05) were less likely to have higher DTI.

Discussion

Consistent with previous research, our findings suggest that CG burden, daily care bother, and RMBPC bother were positively associated with higher DTI. 17,19 However, our study extends the previous research by examining the moderating role of PAC or religiosity in an effort to identify CG resources that may buffer these CG stressors and DTI, using the Pearlin SPM as a conceptual foundation.

For the first research question, results indicated that all 3 types of burden were significantly associated with DTI. That is, the higher levels of CG burden, daily care bother as well as RMBPC bother, the greater DTI. This result is consistent with previous studies, 17,41 and our findings confirm that caregiving burden is of particular concern as it relates to maintaining care for persons with ADRD in noninstitutional, community-based settings.

In answering the second research question by examining the moderating effects of PAC or religious coping on DTI, only the interaction between daily care bother and religious coping was significant. Unlike daily care bother, the ZBI asks the CGs more globally about their feelings related to caregiving and the RMBC asks about the observable behavioral problems of the CRs. Only daily care bother focuses on the everyday tasks and/or bother that a CG experiences. The explanation for this moderating finding is not very clear. Research suggests that attending church services, listening to religious radio, and watching religious television programs all provide CGs with a source of strength to fulfill their CG duties. 42 Moreover, previous research suggests that religious coping may be meaningful for CGs facing the challenges and problems of everyday life. 30 Thus, it is speculated that participants with higher levels of positive religious coping are a group with great inner strengths and meaning attached to caregiving; therefore, when facing similar challenges, they are less likely to think about surrendering their caregiving role. Although the other interactions were not significant, the study finding do suggest that when faced with daily caregiving challenges, CGs may lean on religious coping to find strength to continue caring for their loved one at home rather than in an institutional setting.

Study findings should be interpreted with cautions as limitations exist. As a first step, this study used cross-sectional data collected at baseline to investigate this relationship. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution in terms of causality. As a next step, future studies will combine the baseline and follow-up data to have a clearer picture about the association and causality between caregiving burden and DTI, as well as the roles of religiosity and PAC. Secondly, the REACH II sample makes it difficult to generalize any of the findings to other ADRD caregiving populations. Thirdly, PAC and religious coping may not fully capture the potentially modifiable CG attributes that other studies suggest are associated with DTI (cite Gallagher study). 17 Future work is needed to examine other styles of coping that may be modifiable determinants of CG burden as well as DTI. Finally, it needs to be noted that the moderating effect of religiosity on the association of daily care bother and DTI was very small.

Despite these study limitations, study findings have implications for designing supports and services for ADRD CGs to help lower DTI. First, interventions should include key components that underscore the importance of PAC including expanding psychosocial assessments to include PAC, validating the feelings of CGs who experience PAC, strengthening the social support systems of CG to include others who find caregiving rewarding, facilitating close bonds between the CG and CR through meaningful shared activities, and affirming CG who feel a sense of purpose in caregiving.

Secondly, study findings underscore the importance of religious coping and suggest that services and supports for ADRD CGs may include interventions that encourage the use of religious resources, especially as it relates to daily care bother. For example, daily religious coping activities such as prayer or meditation may be encouraged by clergy. Furthermore, the inclusion of religious coping should be included in psychosocial assessments in order to potentially, as appropriate, explore religious practices that support and comfort ADRD CGs (eg, prayer, reading scripture). Findings further suggest the need for expanding support for faith-based organizations that may already be serving ADRD CGs through activities such as congregation-based support groups that may encourage coping strategies for CG burden. For ADRD CGs who are not engaged in religious activities, we point toward concepts of spirituality such as finding purpose and meaning in life, connectedness with others, peacefulness, harmony, and well-being. 43 Spiritual activities that promote these concepts may offer beneficial psychosocial supports to ADRD CGs outside of formal religious involvement or affiliation.

Finally, study findings bolster support for the creation of policies that better support the growing needs of ADRD CGs and point toward the recommendations of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for person-and-family-centered care. 44 Furthermore, expanding the National Family Caregiver Support Program 45 to increase the development and evaluation of evidence-based ADRD CG interventions in community-based settings is critically important in advancing translational research in this area. Finally, our findings endorse the call from other researchers advocating that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should be tasked with developing, testing, and implementing payment reforms that compel providers to explicitly engage, train, and support family CGs. 46 In closing, the study points toward a need for further research in the area of CG DTI and the potentially modifiable factors that may enhance ADRD caregiving and promote the use of home and community-based care services.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Noelle L. Fields  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0211-6037

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0211-6037

References

- 1. ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE FACTS AND FIGURES. Alzheimer’s Association. 2018. Available at: https://www.alz.org/facts/ Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 2. Arrighi H, Neumann P, Lieberburg I, Townsend R. Lethality of Alzheimer Disease and its impact on nursing home placement. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(1):90–95. doi:10.1097/wad.0b013e31819fe7d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gitlin L. Good news for dementia care: caregiver interventions reduce behavioral symptoms in people with dementia and family distress. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):894–897. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12060774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brodaty H, Woodward M, Boundy K, Ames D, Balshaw R. Prevalence and predictors of burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(8):756–765. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim H, Chang M, Rose K, Kim S. Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2011;68(4):846–855. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gitlin L, Roth D, Burgio L, et al. Caregiver appraisals of functional dependence in individuals with dementia and associated caregiver upset. J Aging Health. 2005;17(2):148–171. doi:10.1177/0898264304274184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hilgeman M, Allen R, DeCoster J, Burgio L. Positive aspects of caregiving as a moderator of treatment outcome over 12 months. Psychol Aging. 2007;22(2):361–371. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harris G, Durkin D, Allen R, DeCoster J, Burgio L. Exemplary care as a mediator of the effects of caregiver subjective appraisal and emotional outcomes. Gerontologist. 2011;51(3):332–342. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Lyketsos C, Schneider L. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer Disease: cross-sectional and longitudinal patient correlates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(10):917–927. doi:10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181d5745d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, Uomoto J, Zarit S, Vitaliano PP. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist. Psychol Aging. 1992;7(4):622–631. doi:10.1037//0882-7974.7.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCaskill G, Burgio L, DeCoster J, Roff L. The use of Morycz’s Desire-to-Institutionalize Scale across three racial/ethnic groups J Aging Health. 2010;23(1):195–202. doi:10.1177/0898264310381275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gaugler J, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman J. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47(2):191–198. doi:10.1097/mlr.0b013e31818457ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gaugler J, Wall M, Kane R, et al. The effects of incident and persistent behavioral problems on change in caregiver burden and nursing home admission of persons with dementia. Med Care. 2010;48(10):875–883. doi:10.1097/mlr.0b013e3181ec557b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gallagher D, Ni Mhaolain A, Crosby L, et al. Self-efficacy for managing dementia may protect against burden and depression in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(6):663–670. doi:10.1080/13607863.2011.562179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tarlow B, Wisniewski S, Belle S, Rubert M, Ory M, Gallagher-Thompson D. Positive aspects of caregiving. Res Aging. 2004;26(4):429–453. doi:10.1177/0164027504264493. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hebert R, Dang Q, Schulz R. Religious beliefs and practices are associated with better mental health in family caregivers of patients with dementia: findings from the REACH study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(4):292–300. doi:10.1097/01.jgp.0000247160.11769.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gallagher D, Ni Mhaolain A, Crosby L, et al. Determinants of the desire to institutionalize in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Demen. 2011;26(3):205–211. doi:10.1177/1533317511400307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pearlin L, Mullan J, Semple S, Skaff M. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. doi:10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaugler J, Edwards A, Femia E, et al. Predictors of institutionalization of cognitively impaired elders: family help and the timing of placement. J Gerontol Series B: Psychological Sciences Social Sciences. 2000;55(4):P247–P255. doi:10.1093/geronb/55.4.p247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun F, Shen H. Coping and positive aspects of caregiving: a cross-cultural study of Chinese dementia caregivers in Phoenix and their counterparts in Shanghai. Alzheimer’s Demen. 2013;9(4):P324. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2013.04.160. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lloyd J, Patterson T, Muers J. The positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: a critical review of the qualitative literature. Dementia. 2016;15(6):1534–1561. doi:10.1177/1471301214564792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kinney J, Stephens M. Hassles and uplifts of giving care to a family member with dementia. Psychol Aging. 1989;4(4):402–408. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.4.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Basu R, Hochhalter A, Stevens A. The impact of the REACH II intervention on caregivers’ perceived health. J Applied Gerontol. 2013;34(5):590–608. doi:10.1177/0733464813499640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, McGinnis KA, Stevens A, Zhang S. Long-term care placement of dementia patients and caregiver health and well-being. JAMA. 2004;292(8):961–967. doi:10.1001/jama.292.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pargament K, Smith B, Koenig H, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig. 1998;37(4):710. doi:10.2307/1388152. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rabinowitz Y, Hartlaub M, Saenz E, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. Is religious coping associated with cumulative health risk? An examination of religious coping styles and health behavior patterns in Alzheimer’s Dementia caregivers. J Relig Health. 2009;49(4):498–512. doi:10.1007/s10943-009-9300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Herrera A, Lee J, Nanyonjo R, Laufman L, Torres-Vigil I. Religious coping and caregiver well-being in Mexican-American families. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(1):84–91. doi:10.1080/13607860802154507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heo G, Koeske G. The role of religious coping and race in Alzheimer’s disease caregiving. J Applied Gerontol. 2012;32(5):582–604. doi:10.1177/0733464811433484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heo G. Religious coping, positive aspects of caregiving, and social support among Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. Clin Gerontol. 2014;37(4):368–385. doi:10.1080/07317115.2014.907588. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Belle S, Burgio L, Burns R, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Folsten MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wisniewski S, Belle S, Coon D, et al. The Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): project design and baseline characteristics. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(3):375–384. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morycz R. Caregiving strain and the desire to institutionalize family members with Alzheimer’s disease. Res Aging. 1985;7(3):329–361. doi:10.1177/0164027585007003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit burden interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Katz S. Studies of illness in the aged. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roth D, Dilworth-Anderson P, Huang J, Gross A, Gitlin L. Positive aspects of family caregiving for dementia: differential item functioning by race. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70(6):813–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tarakeshwar N, Pargament K. Religious coping in families of children with autism. Focus on Autism Other Developmental Disabilities. 2001;16:247–160. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Koenig H, Pargament K, Nielsen J. (1998). Religious coping and health status in medically ill hospitalized older adults. J Nervous Mental Dis. 1998;186:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hair J, Black W, Babin B, Anderson R, Tatham R. Multivariate Data Analysis (Vol. 5, No. 3). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall;1998:207–219. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Spitznagel M, Tremont G, Davis J, Foster S. Psychosocial predictors of dementia caregiver desire to institutionalize: caregiver, care recipient, and family relationship factors. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2006;19(1):16–20. doi:10.1177/0891988705284713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dilworth-Anderson P, Boswell G, Cohen M. Spiritual and religious coping values and beliefs among African American caregivers: a qualitative study. J Applied Gerontol. 2007;26(4):355–369. doi:10.1177/0733464807302669. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koenig H. Concerns about measuring “Spirituality” in research. J Nervous Mental Dis. 2008;196(5):349–355. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816ff796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schulz R, Eden J, eds. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, The National Academies Press, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Administration for Community Living: National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP). 2017. Available at: https://www.acl.gov/programs/support-caregivers/national-family-caregiver-support-program. Accessed August 1, 2018.

- 46. Schulz R, Czaja S. (2018). Family caregiving: a vision for the future. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]