Abstract

Qualitative studies were synthesized to describe perspectives of people with dementia regarding meaningful activities. Themes of connectedness were identified using a meta-ethnography approach. The theme of being connected with self encompasses engagement for continuity, health promotion, and personal time. The theme of being connected with others includes being with others not to feel alone, doing an activity with others, and meaningful relationships. The theme of being connected with the environment encompasses being connected to one’s familiar environment, community, and nature. This synthesis suggests that connectedness is an important motivation for engagement in daily activities. Findings indicate that identifying the underlying motivation for an individual with dementia to engage in different activities is important for matching a person with activities that will be satisfying. This review may inform the development of interventions for engaging people with dementia in meaningful, daily activities and creating connectedness to self, others, and the environment.

Keywords: connectedness, dementia, engagement, meaningful activities, qualitative, synthesis

Introduction

Engagement in personally valued, meaningful activities is an important determinant of successful aging and quality of life in older adults. 1 -3 People with dementia, however, often lack opportunities for such engagement to the extent they need and want. The most common unmet needs of people with dementia reported by themselves and their caregivers involve daytime activities, social company, and psychological distress. 4 -6 This can be due to decreased cognitive abilities, psychological and behavioral symptoms, deliberate social withdrawal outside the home, perceived stigma (or self-stigma) of persons with dementia, and beliefs and strategies of those caring for persons with dementia (eg, focusing on activities that help maintain current functional abilities without considering the individual’s preference and value, de-emphasizing values, and preference in daily activities of persons with dementia). 6 -9 People with dementia use professional supports for daytime activities and social company, but available services for daytime activities and social company may not be meaningful or valued by individuals with dementia or be matched to individuals’ varied interests and abilities. 4 -6,10 Understanding perceptions of people with dementia on meaningful activities, thus, will help better develop activity programs that can fulfill psychosocial needs and maintain or improve quality of life of persons with dementia.

This article aims to synthesize qualitative studies describing how people with dementia perceived meaningful activities. Specifically, the intent is to understand the types of activities that are meaningful to people with dementia and the underlying motivations of people with dementia for engaging in these activities.

Method

Search Strategy

To address the specific aims of this review article, a search was conducted to identify articles on meaningful activities and dementia. Meaningful activities were defined as self-chosen activities derived from an individual’s interests, preferences, values, motivations, pleasure, or sense of the importance of participating in certain activities. 11 The Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type search strategy was used because of its suitability for identifying qualitative studies. 12 Electronic databases (including PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychINFO) were used to identify peer-reviewed journal articles, in English, published between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2013. Initially, 796 articles were identified using the search terms listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Terms Used in Databases

| SPIDER Tool | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| S (Sample) | dement* OR Alzheimer* |

| P of I (Phenomenon of Interest) | “meaningful activit*” OR “daytime activit*” OR “daily activit*” OR engagement OR occupation* OR “quality of life” OR activit* OR meaning* OR valu* |

| D (Design) | interview* OR “focus group*” OR survey* OR questionnaire* OR “case stud*” |

| E (Evaluation) | view* OR experienc* OR opinion* OR perspective* OR belie* OR feel* |

| R (Research type) | qualitative OR “mixed method*” OR ethnograph* OR phenomenology OR “grounded theor*” |

Inclusion Criteria

Once the initial search was completed, articles were selected for inclusion in the synthesis if they were qualitative studies or mixed method studies involving people with dementia living in the community or in residential care homes and included the views of people with dementia on meaningful activities. Studies had to use qualitative methods in collecting and analyzing data and use qualitative interviews as the main method for data collection. Relevant qualitative journal articles were identified without limit to specific type of qualitative study, type of dementia, or age of persons with dementia. Titles and abstracts were reviewed for inclusion criteria. Articles were excluded from this review, if all participants in a study were not people with dementia and if studies did not have findings regarding people with dementia, daily activities, and/or why they wanted to engage in these activities.

Quality Appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) 13 was used for quality appraisal of included qualitative studies. The CASP is a checklist that includes 10 questions assessing a study’s rigor, credibility, and relevance. Studies were not excluded based on study quality so as not to miss potentially valuable findings, but we did want to identify the relatively poorer quality studies. 14 We found no study with fewer than 7 of the 10 points (0 = worst and 10 = best) possible on the CASP checklist (Supplementary Material A).

Analysis

Articles were analyzed using Noblit and Hare’s meta-ethnographic approach. 15 Meta-ethnography is a widely used method for synthesizing multiple qualitative studies with diverse study designs. 16,17 Meta-ethnography uses the authors’ interpretations and explanations of their original qualitative studies as the raw data for the synthesis in addition to the reported quotations of participants. In other words, the revealed themes, perspectives, or concepts from each qualitative study are selected as data for synthesis. 18 This prevents misinterpretation of data from its’ original collector and preserves the meaning of the original text. 19

Noblit and Hare’s meta-ethnographic approach 15 outlines a series of specific steps that were followed in the present synthesis. While reading articles repeatedly, a list of relevant key metaphors (concepts, themes, perspectives, and phrases) was generated to describe the findings of each study. The researcher then compared metaphors of individual studies to one another (called “reciprocal translations”) and created working themes that emerged from the key metaphors. The researcher reviewed the themes that emerged to create new overarching themes that meaningfully integrated and interpreted related concepts. A second researcher checked if themes and subthemes fit well with the original data.

Results

Description of Studies

Among the initially identified 796 articles, a total of 717 articles were excluded based on title and abstract. Further 45 articles were excluded after reading full-text articles. The most frequent reason for excluding studies (97.77%) was that the data did not include perspective of people with dementia about meaningful activities. 20 Other less frequent reasons for excluding studies were participants included older adults without dementia 21 ; the article was a review article 22 ; or data were not collected through interviews. 23

A total of 34 studies met the inclusion criteria described previously. Characteristics of each study are outlined in Supplementary Materials A (a shorter version) and B. It is likely that our findings are typical of people with dementia because they were derived from 34 studies involving participants with varied characteristics. For example, participants in the studies included those living in the community (25 studies) and those in residential care homes (13 studies) and had varied stages and types of dementia and marital status. The included studies also varied in national origin, coming from the United Kingdom (13), Canada (4), United States (3), Australia (3), Sweden (3), Norway (2), Netherlands (2), New Zealand (1), Belgium (1), Israel (1), and Hong Kong (1), and race and ethnicity, involving groups who were Jewish, Black, South Asian, and British Asian. The themes and subthemes developed based on 34 studies’ findings capture common but broad perspectives of people with dementia on meaningful activities.

Description of Themes

Analyses reveled that being connected is an important motivation for people with dementia to engage in activities. Three primary themes regarding connection were identified. Persons with dementia were connected or wanted to be connected to self (theme 1), to others (theme 2), and to the environment (theme 3) through engagement in the individual’s meaningful activities. In order to fully describe these broad themes, each was further conceptualized in terms of subthemes that captured distinct approaches to connectedness. Each of these primary themes is further described by three subthemes. Some subthemes occurred less than the others because the former was more narrowly defined than the latter (eg, subtheme 1a vs subtheme 1c). Table 2 describes definitions of themes and subthemes with one quote that represents each subtheme as an example. More examples of quotes from original studies supporting each subtheme are included in Supplementary Material C.

Table 2.

Definitions of Themes and Subthemes.

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Theme 1. Being connected to self Preference for or engagement in activities to preserve their individual identity and their health | Subtheme 1a. Engagement for continuity 24 -40 Engaging in long-held habits, routines, local traditions, and leisure or work-related activities to maintain previous life-style, long-held beliefs, faiths, values, interests, identity, and culture For example, “Although I am very forgetful now, I try to keep my usual routine, do exercise and read newspapers.” 26 (p596) |

| Subtheme 1b. Strategic participation in activities for health benefits 26 -29,31 -33,35,39,41 -50 Engaging in activities to have enjoyment, satisfaction, and distractions from worries, improve and maintain health and well-being, feel useful, and recover a sense of identity For example, “I read a magazine and it [the worry] disappears.” 35 (p73) | |

| Subtheme 1c. Engagement for personal time and rest 27,29,34,44,51 -53 Engaging in activities by oneself to relax with freedom and peace, and without interruptions from others For example, “Every day I look forward to going for walks…I don’t have to do anything. I just walk. I go places by myself and I can enjoy it without having to talk about it.” 29 (p388) | |

| Theme 2. Being connected to others Preference for or engagement in activities to feel part of a larger social context | Subtheme 2a. Being with others not to be/feel alone 24,42,44,49,54 Having company or social contacts not to be/feel alone For example, “I hate having nobody here … I’d like to know where they all are.” 42 (p566) |

| Subtheme 2b. Doing an activity with others 26,27,29 -31,36,39,44,45,50,51,53,55 Participating in social activities to have social interactions and enjoyment, maintain shared identity and quality of life, promote relationships, and cope with difficulties For example, “… Then they [staff] collect us [me]! I think it is boring too, to lie down, and then you lie there… it is much better to be with the others and doing something… Talking to each other, at least.” 51 (p101) | |

| Subtheme 2c. Meaningful relationships 26,30,39,42,46,49,50,55 Establishing and maintaining meaningful relations with others (eg, family, friends, neighbors, other residents, staff, and health professionals) to overcome loneliness, and feel a sense of acceptance and companionship For example, “My life is lonely…very lonely. My daughter doesn’t come to see me; none of my children come to see me. Sometimes I would like to talk to one or other of them.” 46 (p1447) | |

| Theme 3. Being connected to environment Preference for or engagement in activities to maintain the connection to the physical environment | Subtheme 3a. Being connected to one’s own home and familiar environment 27,41,54,56 Being connected to one’s own home and personal items that give feelings of peace and comfort, help coping and maintaining identity, and facilitate participation in activities For example, “I don’t want to do anything wrong … I don’t want to make any big mistakes or anything … [friend’s name] made mistakes and then they would put her in the old people’s home.” 54 (p274) |

| Subtheme 3b. Being connected to community 39,54,56 Being connected to a community that helps overcome loneliness, gives a sense of belonging, and promotes quality of life For example, “I’ve been involved in the church all my life. It’s just a part of me.” 37 (p591) | |

| Subtheme 3c. Being connected to nature 42,50,52,57 Being connected to nature in a way that gives enjoyment, pleasure, and stimulation and promotes participation in activities For example, “Being homely means being able to look out the window and liking what you’re looking at … Just normal things around you like a garden and animals, that’s what I see as homely.” 56 (p2616) |

Theme 1: Being connected to self

Subtheme 1a

Engagement for continuity. Community-dwelling people with early and middle stages of dementia had a significant desire for continuing engagement in typical everyday activities that they had done before the dementia to maintain some level of continuity with their previous lifestyle, long-held beliefs, and values. 24 -34 For example, staying interesting was a value for one woman with dementia who kept watching TV programs of interest to her, reading books, and meeting friends to maintain her value of being an interesting person. 28 Two of the males had past lifestyles of hard work and valued achievement through hard work. 30 Having no activity that required hard work to achieve a goal caused these men to feel empty and uncomfortable. They therefore tried to continue engaging in daily activities, including work-related activities, to maintain their identities.

Activities supporting each individual’s habits, routines, and roles were meaningful because people with dementia could engage in these daily activities as much as possible, feel a sense of normality, and maintain their preferred lifestyle. 27 -29,31,33,35 Remaining involved in work-related activities and household chores helped some people with dementia maintain a sense of role identity; one as a previous choral conductor, another as a helpful husband for his wife with a disability, and a third as a good father for his children. 29 Helping others was another important way of maintaining continuity of lifestyle to one person with dementia related to his previous occupational role as a teacher. 25

Continuing engagement in cultural and spiritual activities helped people with dementia maintain their culture and long-held faiths. Community-dwelling older adults with early stage dementia valued cultural activities related to traditions, local history, folk music, and their own life histories. 36 Some people with dementia continued participating in spiritual activities by engaging in personal practices at home (eg, prayer and reading the Bible), attending church, playing roles and helping others in church, and by being informed of events within the wider spiritual communities. 37 -40 They were strongly motivated to engage in these spiritual activities because of their sense of identity and continuity in faith, and the fellowship with and support from other members in the spiritual community.

Subtheme 1b

Strategic participation in activities for one’s own health benefits. Community-dwelling people with dementia found enjoyment, satisfaction, and distraction from other worries by engaging in leisure activities, such as gardening, going for walks, music activities, and communal activities. 29,35,41 Listening to music and singing were identified as common past and current leisure activities, and these activities were not too demanding to do, so people with dementia could actively engage in these activities with pleasure and without thinking about dementia. 32,39,42,43 Music-related activities were also enjoyed by people with dementia because of positive benefits to their mood and concentration by soothing and uplifting their spirits and expressing themselves nonverbally. 44,45 Background music also promoted participation in routine activities by making activities more enjoyable. 45

Engaging in intellectual, physical, and leisure activities (eg, reading, doing crossword puzzles, and going out for daily walks) was meaningful to community-dwelling people with dementia because they believed that these activities would improve memory and restore their abilities. 28,32,35,41 Some women with dementia, for example, watched TV believing this would help maintain an active mind. 33 Intellectual activities, however, were avoided or abandoned if the people with dementia regarded that activity as too demanding. 27,35 Keeping an active mind, being physically active, and maintaining health and well-being were of great value to people with dementia who strategically participated in such activities to produce a sense of improved well-being. 26 -28,41 Older people with early stage dementia engaged in leisure activities and organized programs to keep busy and occupied and thus to reduce loneliness and get some distractions from social isolation. 33,46

Being or feeling useful helps older adults with dementia feel valuable to others and provides a sense of self-worth. 32,47 Some community-dwelling people with dementia maintained feeling valued and a sense of purpose by doing household chores for their busy children. 33,47 Finding new ways of feeling useful was meaningful to community-dwelling people with early stage dementia. One new way was participating in Alzheimer’s research, which provided them with an opportunity to reflect on their experiences and feel useful through the interview process. 31,48 Residents with dementia in care homes also expressed frustration and a need for feeling useful. 49,50 The search by residents for active engagement in useful activities helped them feel more satisfied with living in care homes. 49

Reviewing past experiences and one’s life was pleasurable to residents with dementia living in care homes because engaging in this activity recovered their sense of identity by compensating for their current losses. 49 Talking about past activities, experiences, and interests associated with one’s social and occupational roles were enjoyed and meaningful to people with dementia as an expression of their identity. 27,44 Looking back over pleasurable memories was a way for an individual with early stage dementia to enjoy being alone and not to feel lonely. 46

Subtheme 1c

Engagement for personal time and rest. People with dementia considered having time alone 44 and rest 51 meaningful to them. Walking outdoors by oneself was one activity that provided relaxation and a low level of social stress. 29,52 Having quiet meals alone was a way of connecting with self by allowing time for being with one’s own thoughts. 53 Being in a private space alone and engaging in activities in the private space provided people with dementia with feelings of freedom, peace, and enjoyment. 27,34

Theme 2: Being connected to others

Subtheme 2a

Being with others not to be/feel alone. Having company was meaningful to people with dementia to avoid being or feeling alone. Attending day care centers with highly satisfying levels of human contact was enjoyable to community-dwelling people with dementia. 24 Having social contact was also significantly important to residents with dementia regardless of their stages of dementia. 42,44 Residents with middle and late stages of dementia in care homes expressed fear of being alone and loneliness due to a socially isolated life at care homes. 49 Those living alone listened to the radio and watched TV in order not to feel alone and to feel a sense of connection to others by having virtual company. 54

Subtheme 2b

Doing an activity with others. Doing things together with others in a day care center promoted a sense of belonging and motivation for engagement in activities. 29 Working together in the garden was a meaningful activity to a man with dementia and his family because of a sense of shared identity as the family who worked hard together with partnership to overcome any challenge. 30 Some community-dwelling people with dementia regarded “doing things together with my partner” as an activity that positively affected their quality of life. 39 (p542) Residents with dementia in care homes were motivated to participate in group activities (eg, newspaper reading and gymnastics) offered in care homes because of a sense of belonging by doing things together with others. 51 The residents found more enjoyment in some group activities matched with their abilities and interests so that they could participate equally with others. Activities involving music, such as singing together and dancing, encouraged social interaction by being physically and emotionally close with others. 45 Engagement in cultural activities with others who shared local life experiences also facilitated their feelings of belonging by culture not by dementia itself. 36

Talking to or sharing with others was a meaningful activity for people with dementia, and the personality and attitude of the person they talked to made a difference as to whether they felt at ease and connected to others. 26 Talking and sharing with similar people, in terms of dementia or unrelated to dementia (eg, attending a women’s group), helped people with early stage dementia normalize difficulties, learn different ways of coping from others, and not to feel alone. 31 Talking to and about family gave residents feelings of being connected to their families by reminding residents with dementia of past memories and proving their existence outside of care homes. 44,50 Couples reminisced together about their shared history, especially positive memories, to maintain their shared sense of identity and couplehood and to offset their current difficult situations. 55 Looking at personally significant items (eg, family photographs, cushions made by a family member) and talking about related stories helped people with dementia maintain feelings of connection with family as well as connection with themselves. 27 Listening to music also helped people with dementia recall past memories and thus encouraged meaningful conversations with others by talking about their past experiences. 45

Subtheme 2c

Meaningful relationships. Older people with dementia who lived in either the community or long-term care facilities desired maintenance of meaningful relationships, and a loss of key relationships was a source of loneliness. 39,42,46 Some older residents with dementia felt hurt and sad when their family did not visit the homes and care for them as much as the people with dementia expected and as they had done for their families in earlier years. 50 Understanding and accepting that family members could not visit the home often helped residents with dementia maintain positive relationships with family members and a sense of acceptance by family even if the family visits were fewer than they wished. 49 Some people with dementia desired to maintain positive meaningful relationships by receiving support and love from their family, and by being respected for their remaining abilities, their autonomy, and their continued usefulness. 26 Participating in weekly get-togethers at a local café was a meaningful family ritual for one man with dementia and his family. 30 He did not actively engage in conversations, but he valued maintaining relationships with families and felt a sense of belonging. Some couples maintained their relationships and couplehood by trying to be active and sociable together, for instance, going out for Sunday lunch and doing crosswords together. 55

Theme 3: Being connected to environment

Subtheme 3a

Being connected to one’s own home and familiar environment. People with dementia want to stay in their homes because of feelings of peace and comfort at home where their life histories and memories are embedded. 41,54 Moving to a nursing home can be a significant threat to people who have a strong tie to home and value independent living. Engagement in safety maintenance activities by using a checking strategy, paying extra attention, and avoiding any activity that is beyond their current abilities were important for people with dementia living alone to stay at home and not move to a nursing home. 54 Being in familiar environments promoted a sense of coherence for people with dementia and these feelings supported participation in activities, including taking walks, shopping, and using public transportation in the familiar environment where they had grown up. 27 Being in the familiar environment with personal things such as photographs, furniture, plants, decorations, and other memorabilia, supports the continuation of self and provides the person with dementia with feelings of being at home. 56

Subtheme 3b

Being connected to community. Some older people living alone may feel confined at home as they lose the ability to drive and do not have close social contacts they can socialize with frequently. 54 Looking out through a window at home was a way they could feel connected to their communities. One woman with dementia living alone found enjoyment in being out in the community when she went out for groceries by seeing other people and feeling good in the fresh air. Being involved in the things around self and being interested in what is happening in the world were important for quality of life in both community-dwelling older people and nursing home residents with dementia. 39 Participating in activities that give an atmosphere of community (eg, parties, barbecues, and celebrations of national events) was valued. 56

Subtheme 3c

Being connected to nature. Being in nature and the enjoyment and positive feelings derived from it were strong motivations for daily walks in community-dwelling men with early stage dementia. 52 Pleasure from being connected to nature strengthened their value of staying physically active by making a routine of daily walks. The men and their wives used adaptive strategies for the men to continue engaging in outdoor walks themselves in order to compensate for their reduced ability due to dementia and to feel secure while walking. Being outdoors and gardening were important to residents with middle stage dementia because of the stimulation and pleasure nature provides. 42 (p567) Outside activities such as walking were not allowed in some care homes because of safety issues, and residents with dementia expressed how much they enjoyed participating in these activities in the past. 50

Theme Interactions

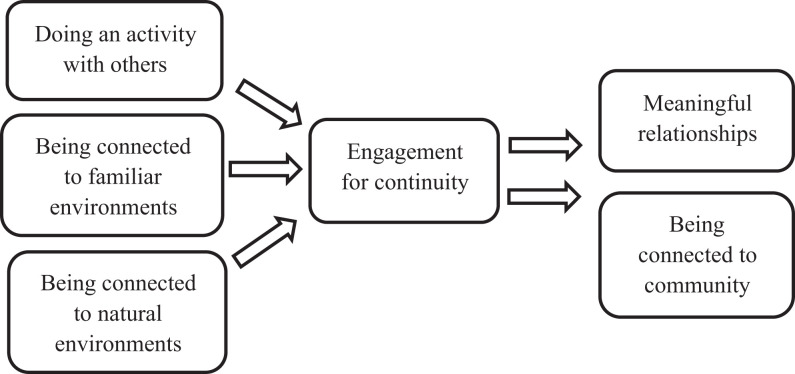

In addition to identifying unique themes, meta-ethnography also requires that interactions among themes be considered. Our analysis indicates that motivation for activities in a number of subthemes also fulfilled the activity needs described under other subthemes (see Figure 1). For example, engagement for continuity facilitated maintaining meaningful relationships and being connected to the community. Families or friends helped people with dementia continue engaging in activities matched with lifestyles, lifelong beliefs, values, and interests. For example, a wife left a note with instructions and schedules for her husband with dementia every morning to help him plan his day, engage in work-related activities, go out on errands, and go to church with his son. 29 These supports from his wife promoted not only continuing engagement but also a sense of connection to his wife and the community. Going to church also facilitated a sense of belonging to the spiritual community and meaningful relationships from church members as well as maintenance of spiritual identity and faiths. 38 Engagement for continuity was strengthened while doing an activity with others, being connected to familiar environments, and being connected to natural environments. Working together in the garden allowed a man with dementia and his family to maintain a sense of shared identity, 30 and reminiscing shared histories together promoted maintenance of their shared sense of identity and couplehood. 55 Being in familiar environments supported continuing engagement in daily activities and a continuation of self-identity. 27,56 Enjoyment from being in nature facilitated continuing engagement of staying physically active by making daily walks a routine. 52

Figure 1.

Theme interactions.

Discussion

The purpose of the present synthesis was to integrate the findings of qualitative studies on meaningful activities from the perspective of people with dementia. Our focus was on identifying the activities that are meaningful to people with dementia and the reasons that they want to engage in these activities. We found that being connected is a strong motivation for engaging in activities and engagement in meaningful activities helps the person with dementia to be connected. The findings indicate that being connected in personally meaningful ways promotes a sense of belonging along with physical, mental, and emotional health, self and social identity, independence, interdependence, and life satisfaction in people with dementia. Individual differences in ways of being connected depended on values, beliefs, interests, culture, living environment, and previous lifestyles and roles. The common meaning and motivation for engagement, however, was to be connected to self, others, and environment.

In addition to these findings about the importance of connectedness, findings from the studies synthesized here also highlight the importance of understanding each individual’s motivation for participating in a given activity. Different individuals may engage in the same activity but for different reasons or to meet different needs. Watching TV, for example, was meaningful to maintain the value of being an interesting person, 28 maintaining an active mind, 33 or not feeling alone. 54 Conversely, individuals may engage in activities that are very different on the surface, but that are motivated by a desire to meet the same need. For example, sharing a meal and gardening activities may both meet the need of being connected with one’s spouse. Thus, the critical aspects of activity are that it is personally meaningful to the individual with dementia, and that it meets their individual need. When there are mismatches between the meaning of an activity for a person with dementia and a caregiver’s perception about the meaning of that activity, frustration and conflict may occur. For example, family caregivers and staff valued social activities organized by care homes more than contact with family, whereas individuals with dementia often most highly valued contact with family. 44 Family caregivers also had little awareness that reminiscence activity and music activity were important to their relatives with dementia 44 and reported difficulty in finding meaningful activities for their loved ones. 52 Similar mismatches may be present between people with dementia and paid caregivers. In one study, being useful and maintaining religious faith was reported by people with dementia as being important for their quality of life but was not mentioned as important to their care recipients by professional caregivers. 39 These findings underscore the importance of identifying the nature and scope of meaningful activities from the perspective of people with dementia when providing person-centered care.

Understanding why the person with dementia wants to engage in a particular activity is important for caregivers and health professionals to be able to support the connectedness of people with dementia. As dementia progresses, the individual may not be able to engage in his or her valued, meaningful activity even by using compensation strategies or adaptive tools or equipment. In that case, an alternative activity could be substituted that is matched with the value or need embedded in the previous activity. Without understanding why the particular activity was important to the person with dementia, the proposed alternative activity may not be successful. One man with dementia, for instance, liked cycling because of being connected to nature. After moving to a long-term care setting, the staff knew he liked cycling and assumed that he enjoyed physical activity. They asked him to ride the indoor bicycle without knowing why he liked cycling, and he is unlikely to enjoy or want to engage in cycling when the activity is disconnected from nature. In this case, he may enjoy walking in the garden more than riding the indoor bicycle.

The cycling example just described illustrates why health professionals and caregivers should make an effort to understand the underlying meaning of engagement in activity and help the person with dementia express and engage in activities matched with their psychosocial needs, especially as dementia progresses. An awareness of connectedness as an important motivation for engagement, and of the variety of ways of being connected, will facilitate development of better interventions and care for people with dementia. Further studies are needed to identify how best to tailor interventions to meet an individual’s need and desire to be connected to self, others, and environment to assure psychosocial well-being and quality of life in people with dementia.

And finally, our findings are consistent with earlier work by Register and Herman who theorized that six interrelated processes of being connected (metaphysically connected, spiritually connected, biologically connected, connected to others, environmentally connected, and connected to society) were critical to quality of life for the elderly individuals. 58 (p344) In an evaluation of this theory in a qualitative study of community-dwelling older adults, Register and Scharer reported four processes involved with being connected in older adults, including (1) having something to do, (2) having relationships, (3) having a stake in the future, and (4) having a sense of continuity. 59 (p471) Together with the present study, these findings suggest that being connected to self, others, and environments is an important motivation for engagement in personally meaningful activities for both healthy older adults and adults with dementia. Especially, helping persons with dementia feel a sense of continuity through engagement in personally meaningful activities should be encouraged to caregivers who may increasingly de-emphasize values and preferences of persons with dementia in daily activities. 9

The present study has several strengths including the use of a meta-ethnography approach in synthesizing qualitative studies and involvement of participants with varied characteristics. The present study included multiple qualitative studies with diverse study designs and participants with varied characteristics while preventing misinterpretation of data from its’ original collector and preserving the meaning of the original text. A limitation of the present study is that only one researcher reviewed the literature and determined the eligibility of the searched studies for inclusion. Although over 700 studies were searched by the first author, the absence of another independent researcher in this process might have helped to identify additional relevant studies.

Conclusion

The aim of the synthesis of qualitative studies reported here was to identify the meanings of engagement in daily activities based on perspectives of people with dementia. Our analysis indicates that persons with dementia want to engage in personally meaningful activities to be connected with self, with others, and with the environment. These findings support the premise that being connected is an important motivation for engagement in daily activities, and underscore the importance of understanding this underlying motivation for designing person-centered activities to achieve connectedness and meet the psychosocial needs of persons with dementia. Caregivers should help persons with dementia continue engagement in personally meaningful activities, by better understanding the person’s want and need for engagement in activities and identifying varied ways of being connected in a personally meaningful way. Future studies are needed to identify if interventions tailored to meet an individual’s need for being connected to self, others, and environment affect psychosocial well-being and quality of life of people with dementia. These interventions may benefit people with dementia better than interventions that only emphasize increasing activity level and stimulation.

Footnotes

This article was accepted under the editorship of the former Editor-in-Chief, Carol F. Lippa.

Authors’ Note: Areum Han created the research question, searched and reviewed the literature, and wrote the manuscript. Jeff Radel helped in creating the research question, checked if emerging themes were well-grounded, and contributed to revising the manuscript. Joan McDowd contributed to revising the manuscript. Dory Sabata contributed to revising the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: The online data supplements are available at http://aja.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- 1. Bowling A. Enhancing later life: how older people perceive active ageing? Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(3):293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stenner P, McFarquhar T, Bowling A. Older people and ‘active ageing’: subjective aspects of ageing actively. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(3):467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilhelmson K, Andersson C, Waern M, Allebeck P. Elderly people’s perspectives on quality of life. Ageing Soc. 2005;25(4):585–600. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hancock GA, Woods B, Challis D, Orrell M. The needs of older people with dementia in residential care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(1):43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miranda-Castillo C, Woods B, Orrell M. The needs of people with dementia living at home from user, caregiver and professional perspectives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Roest HG, Meiland FJM, Comijs HC, et al. What do community-–dwelling people with dementia need? A survey of those who are known to care and welfare services. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(5):949–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cook C, Fay S, Rockwood K. Decreased initiation of usual activities in people with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a descriptive analysis from the VISTA clinical trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(5):952–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burgener SC, Buckwalter K, Perkhounkova Y, Liu MF. The effects of perceived stigma on quality of life outcomes in persons with early-stage dementia: longitudinal findings: part 2. Dementia. 2013:1–24. doi:10.1177/1471301213504202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reamy AM, Kim K, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Values and preferences of individuals with dementia: perceptions of family caregivers over time. Gerontologist. 2013;53(2):293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donath C, Winkler A, Graessel E, Luttenberger K. Day care for dementia patients from a family caregiver’s point of view: a questionnaire study on expected quality and predictors of utilisation—part II. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trombly CA. Occupation: purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms: 1995 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. Am J Occup Ther. 1995;49(10):960–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CASP UK. Critical Skills Appraisal Programme (CASP): Making sense of evidence.10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Web site. http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_951541699e9edc71ce66c9bac4734c69.pdf. Published 2006. Updated May 31, 2013. Accessed January 10, 2014.

- 14. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(4):209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cook C, Fay S, Rockwood K. A meta-ethnography of paid dementia care workers’ perspectives on their jobs. Can Geriatr J. 2012;15(4):127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(43):1–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weed M. “Meta interpretation”: a method for the interpretive synthesis of qualitative research. Forum Qual SocRes. 2005;6(1):37. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beard RL, Fetterman DJ, Wu B, Bryant L. The two voices of Alzheimer’s: attitudes toward brain health by diagnosed individuals and support persons. Gerontologist. 2009;49(suppl 1):S40–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murphy K, Shea EO, Cooney A. Quality of life for older people living in long-stay settings in Ireland. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(11):2167–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Boer ME, Hertogh CMPM, Dröes R-M, Riphagen II, Jonker C, Eefsting JA. Suffering from dementia—the patient’s perspective: a review of the literature. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(6):1021–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palo-Bengtsson L, Winblad B, Ekman S. Social dancing: a way to support intellectual, emotional and motor functions in persons with dementia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 1998;5(6):545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aggarwal N, Vass AA, Minardi HA, Ward R, Garfield C, Cybyk B. People with dementia and their relatives: personal experiences of Alzheimer’s and of the provision of care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2003;10(2):187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Menne HL, Kinney JM, Morhardt DJ. ‘Trying to continue to do as much as they can do’: theoretical insights regarding continuity and meaning making in the face of dementia. Dementia. 2002;1(3):367–382. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mok E, Lai CKY, Wong FLF, Wan P. Living with early-stage dementia: the perspective of older Chinese people. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59(6):591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Öhman A, Nygård L. Meanings and motives for engagement in self-chosen daily life occupations among individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. OTJR. 2005;25(3):89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Phinney A. Living with dementia: from the patient’s perspective. J Gerontol Nurs. 1998;24(6):8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Phinney A, Chaudhury H, O’Connor DL. Doing as much as I can do: the meaning of activity for people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(4):384–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Phinney A, Dahlke S, Purves B. Shifting patterns of everyday activity in early dementia: experiences of men and their families. J Fam Nurs. 2013;19(3):348–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Preston L, Marshall A, Bucks RS. Investigating the ways that older people cope with dementia: a qualitative study. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(2):131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith SC, Murray J, Banerjee S, et al. What constitutes health-related quality of life in dementia? Development of a conceptual framework for people with dementia and their carers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(9):889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van Dijkhuizen M, Clare L, Pearce A. Striving for connection: appraisal and coping among women with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia. 2006;5(1):73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Zadelhoff E, Verbeek H, Widdershoven G, van Rossum E, Abma T. Good care in group home living for people with dementia. Experiences of residents, family and nursing staff. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(17-18):2490–2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nygård L, Öhman A. Managing changes in everyday occupations: the experience of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. OTJR. 2002;22(2):70–81. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brataas HV, Bjugan H, Wille T, Hellzen O. Experiences of day care and collaboration among people with mild dementia. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(19-20):2839–2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beuscher L, Grando VT. Using spirituality to cope with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. West J Nurs Res. 2009;31(5):583–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dalby P, Sperlinger DJ, Boddington S. The lived experience of spirituality and dementia in older people living with mild to moderate dementia. Dementia. 2012;11(1):75–94. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dröes R, Boelens-Van Der Knoop ECC, Bos J, et al. Quality of life in dementia in perspective: an explorative study of variations in opinions among people with dementia and their professional caregivers, and in literature. Dementia. 2006;5(4):533–558. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lawrence V, Samsi K, Banerjee S, Morgan C, Murray J. Threat to valued elements of life: the experience of dementia across three ethnic groups. Gerontologist. 2011;51(1):39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gilmour JA, Huntington AD. Finding the balance: living with memory loss. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005;11(3):118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cahill S, Diaz-Ponce AM. ‘I hate having nobody here. I’d like to know where they all are’: can qualitative research detect differences in quality of life among nursing home residents with different levels of cognitive impairment? Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(5):562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cohen-Mansfield J, Golander H, Arnheim G. Self-identity in older persons suffering from dementia: preliminary results. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(3):381–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harmer BJ, Orrell M. What is meaningful activity for people with dementia living in care homes? A comparison of the views of older people with dementia, staff and family carers. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(5):548–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sixsmith A, Gibson G. Music and the wellbeing of people with dementia. Ageing Soc. 2007;27(1):127–145. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moyle W, Kellett U, Ballantyne A, Gracia N. Dementia and loneliness: an Australian perspective. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(9/10):1445–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Steeman E, Godderis J, Grypdonck M, De Bal N, De Casterlé BD. Living with dementia form the perspective of older people: is it a positive story? Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(2):119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Clare L. Managing threats to self: awareness in early stage Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(6):1017–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Clare L, Rowlands J, Bruce E, Surr C, Downs M. The experience of living with dementia in residential care: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Gerontologist. 2008;48(6):711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moyle W, Venturto L, Griffiths S, et al. Factors influencing quality of life for people with dementia: a qualitative perspective. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(8):970–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Holthe T, Thorsen K, Josephsson S. Occupational patterns of people with dementia in residential care: an ethnographic study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2007;14(2):96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cedervall Y, Åberg AC. Physical activity and implications on well-being in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a qualitative case study on two men with dementia and their spouses. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010;26(4):226–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Keller HH, Martin LS, Dupuis S, Genoe R, Edward HG, Cassolato C. Mealtimes and being connected in the community-based dementia context. Dementia. 2010;9(2):191–213. [Google Scholar]

- 54. De Witt L, Ploeg J, Black M. Living on the threshold: the spatial experience of living alone with dementia. Dementia. 2009;8(2):263–291. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Molyneaux VJ, Butchard S, Simpson J, Murray C. The co-construction of couplehood in dementia. Dementia. 2012;11(4):483–502. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Edvardsson D, Fetherstonhaugh D, Nay R. Promoting a continuation of self and normality: person-centred care as described by people with dementia, their family members and aged care staff. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(17-18):2611–2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gibson G, Chalfont GE, Clarke PD, Torrington JM, Sixsmith AJ. Housing and connection to nature for people with dementia: findings from the INDEPENDENT project. J Hous Elderly. 2007;21(1-2):55–72. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Register ME, Herman J. A middle range theory for generative quality of life for the elderly. Adv Nurs Sci. 2006;29(4):340–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Register EM, Scharer KM. Connectedness in community-dwelling older adults. Western J Nurs Res. 2010;32(4):462–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]