Abstract

The role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been evaluated in many studies. We performed a meta-analysis to summarize the existing evidence on the relation between use of classical NSAIDs and AD. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the role of classical NSAIDs in AD was searched using different search engines. The RCTs in patients who had the degree of AD measured on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or AD Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) were included in the study. The RCTs and data (AD scores) were independently assessed by 2 reviewers, and data were included in meta-analysis only after a common consensus was reached. The pooled results from the ADAS-cog and MMSE scores failed to show any difference between the treatment and the placebo groups as opposed to findings from some observational studies. However, in view of heterogeneity of results, there is a need to conduct more RCTs to arrive at confirmatory findings.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, MMSE, ADAS-cog

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia. An estimated 5.2 million Americans from different age-groups have AD in 2013. The total number of patients with AD dementia in 2050 is projected to be 13.8 million, with 7.0 million aged 85 years or older. 1

Only symptomatic relief is being offered by the current therapeutic interventions and none being able to halt disease progression or reverse its symptoms. 2 Cholinesterase inhibitors have consistently shown symptomatic benefits and are now recognized as the standard treatment in patients with mild to moderate AD. 3

The role of inflammation in AD has been extensively studied over the last 2 decades pointing toward a central role of inflammation in AD pathogenesis. 2,4 –7 Microglia, the primary immune cells of the brain, is activated in AD and is predictive of symptom severity. 2 The role of inflammatory mediators in AD-associated dysfunction of neurosupportive cells like astrocytes and oligodendrocytes has been established by the several studies. Also, results from preclinical studies indicated the effect of immune proteins like cytokine and chemokine on amyloidosis, neurodegeneration, and cognition. 6 These studies provide evidence that inflammation plays a significant role in pathophysiology of AD.

Among the anti-inflammatory compounds, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were considered the most promising by these studies. Although several distinct actions have been described for the mechanism of action of NSAIDs, the classical NSAIDs primarily inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) activity. Although both COX-1 and COX-2 are expressed in the brain under normal conditions, the localization of COX-1 in microglia and the regulation of COX-2 by inflammatory mediators suggest that these enzymes could be involved in the neuroinflammatory response in AD.

Many clinical trials seem to provide evidence that NSAIDs are associated with reduction in the risk of developing AD and slower progression and decreased severity of dementia 8,9 ; however not all the clinical trials have supported the fact. Some of the recent randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials failed to detect any effect on cognition impairment by classical NSAIDs in mild to moderate patients with AD, 10 while others reported a trend toward reduced cognitive decline over 12 months, which again failed to reach statistical significance. 11 Epidemiological studies suggest that the use of NSAIDs can prevent or retard the development of AD. 12

Studies evaluating effects of classical NSAIDs on AD progression have yielded mixed or inconclusive results. So, we performed a meta-analysis to summarize the existing evidence on the association between use of classical NSAIDs and AD.

Methods

Search Strategy

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) related to role of traditional NSAIDs in AD were searched using MEDLINE, EMBASE, and COCHRANE databases from their beginning till 2013, using search string (Alzheimer OR AD) AND nsaid AND (randomized controlled trial .pt). The cross-references found in these journals were thoroughly checked.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) only randomized trials were included as a part of this review; (2) patients with a history or at risk of AD were included; and (3) patients who had the degree of AD were measured on at least 1 of the following scales: Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or AD Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog).

Data Extraction

The scores related to the severeness of AD (MMSE and ADAS-cog) in both NSAIDs and control arms were included.

Assessment of RCTs and Scores for Evaluation of AD

Randomized controlled trials and data related to AD scores were independently assessed by 2 reviewers, and data were included in meta-analysis only after a common consensus was reached.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluation was done by a method described by Neyeloff et al. 13 For continuous outcomes data, a weighted mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a random effects model if significant heterogeneity is expected. Heterogeneity was tested for all combined results by means of a Q test (using a chi-square analysis), and inconsistency was calculated using an I2 index to determine the impact of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity quantified by I2 statistic was interpreted as 0% to 40% (might not be important), 30% to 60% (may represent moderate heterogeneity), 50% to 90% (may represent substantial heterogeneity), and 70% to 100% (considerable heterogeneity). 14 A sensitivity analysis for both the parameters (MMSE and ADAS-cog) was performed to assess the effect of individual study on pooled results.

Results

The search yielded potential 635 studies, of which 15 studies were RCTs. Of these studies, those which reported the desired end points were pooled for meta-analysis. A total of 7 studies satisfying inclusion criteria were included in this analysis. All were placebo-controlled blinded, randomized trials on aged patients undergoing treatment with traditional NSAIDs. The number of patients and inclusion criteria for each study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies Included in the Meta-analysis.

| Study, year | Number of Patients Intervention/Placebo | Inclusion Criteria | Mean Age, years | Treatments | Parameter Evaluated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical NSAIDs | Aisen et al, 15 2003 | 240/111 | MMSE: 13-26 | >50 | Naproxen/placebo | ADAS-cog |

| De Jong et al, 11 2008 | 26/25 | MMSE: 10-26 | >70 | Indomethacin/placebo | ADAS-cog, MMSE | |

| Hüll and Bauer, 16 1999 | 7/3 | Diagnosed AD | >55 | Piroxicam/placebo | ADAS-cog | |

| Pasqualetti, et al, 17 2009 | 66/66 | Probable or possible AD | >65 | Ibuprofen/placebo | ADAS-cog, MMSE | |

| Rogers et al, 18 1993 | 14/14 | MMSE > 16 | Not limited | Indomethacin/placebo | ADAS-cog, MMSE | |

| Scharf et al, 19 1999 | 12/15 | MMSE:11-25 | >50 | Diclofenac and misoprostol/placebo | ADAS-cog, MMSE | |

| ADAPT, 20 2008 | 1445/1083 | History of first degree dementia | >70 | Naproxen/placebo | MMSE |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

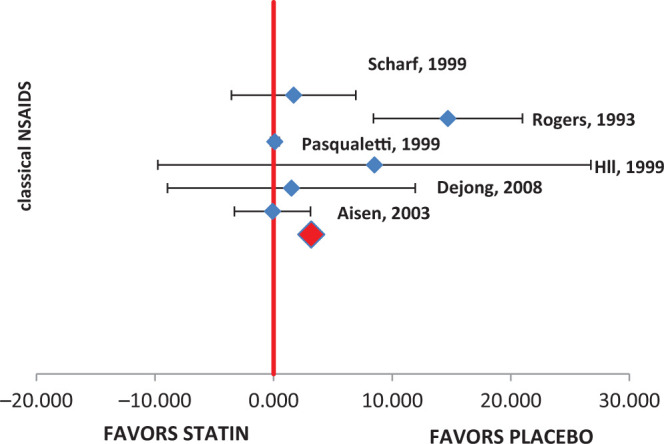

Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale

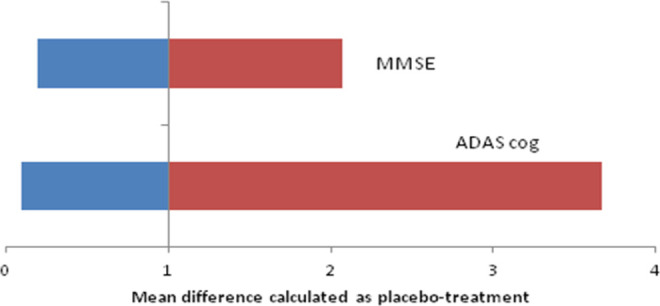

The following 6 studies were evaluated for ADAS-cog change from baseline: Aisen et al, 15 De Jong et al, 11 Hüll and Bauer, 16 Pasqualetti et al, 17 Rogers et al, 18 and Scharf et al. 19 The mean change and standard deviation were collected from the literature, and meta-analysis was performed. The combined results showed that there was no significant difference between the treatment and the placebo group (mean difference: 3.17, 95% CI: −0.70 to 7.04, P = .08). The Q statistic, I2 values, and P value for distribution showed that data were heterogeneous (77.07). Data from Rogers et al, 18 Scharf et al, 19 Pasqualetti et al, 17 Hüll and Bauer, 16 and De Jong et al 11 studies were in favor of placebo arm, while the pooled result shows that there is no significant difference between the treatment and the placebo arms. The pooled results obtained from the analysis are presented in Table 2. The forest plot is presented in Figure 1. The range of mean difference (0.099-3.67) is presented in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Result Summary for ADAS-cog Obtained From Meta-analysis.a

| Class | Study/subgroup | Placebo | Treatment | Weight, % | Mean Differenceb | 95% CI (Lower) | 95 % CI (Upper) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | ||||||

| Classical NSAIDs | Aisen, 15 2003 | 5.7 | 8.20 | 56 | 5.8 | 8.00 | 118.00 | 23.72 | −0.10 | −2.69 | 2.49 |

| De Jong et al, 11 2008 | 9.3 | 10.00 | 19 | 7.8 | 7.60 | 19.00 | 9.25 | 1.50 | −4.15 | 7.15 | |

| Hüll and Bauer, 16 1999 | 10.0 | 8.49 | 2 | 1.5 | 4.46 | 6.00 | 3.88 | 8.50 | −3.80 | 20.80 | |

| Pasqualetti, et al, 17 2009 | 3.1 | 1.30 | 66 | 3 | 1.30 | 66.00 | 28.27 | 0.10 | −0.34 | 0.54 | |

| Rogers et al, 18 1993 | 13.3 | 5.60 | 14 | −1.4 | 4.90 | 14.00 | 16.21 | 14.70 | 10.80 | 18.60 | |

| Scharf et al, 19 1999 | 1.93 | 5.55 | 14 | 0.25 | 4.50 | 17.00 | 18.66 | 1.68 | −1.93 | 5.29 | |

| Total (95% CI) | 171 | 240 | 100 | 3.17 | −0.70 | 7.04 | |||||

| Heterogenity | Q = 21.8 | P < .001 | I2 = 77.07 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale.

a Sensitivity: 0.099 to 3.67.

b Mean difference was calculated as placebo treatment.

Figure 1.

Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) forest plot.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analysis.

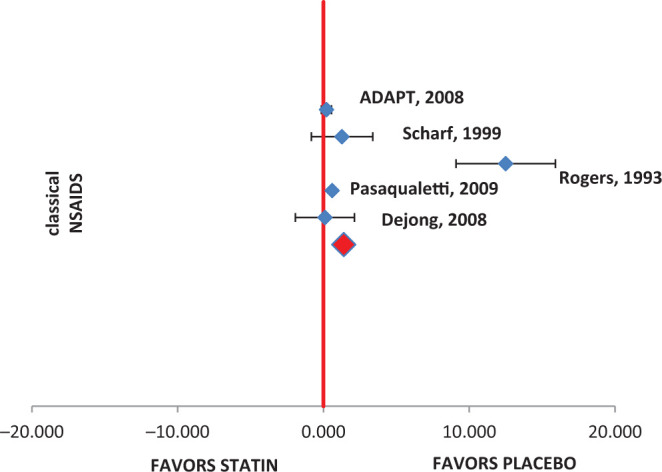

Mini-Mental State Examination

The following 5 studies were evaluated for MMSE change from baseline: De Jong et al, 11 Pasqualetti et al, 17 Rogers et al, 18 Scharf et al, 19 and Alzheimer's Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT). 20 The mean change and standard deviation were collected from the literature, and meta-analysis was performed. The combined results showed that there was no significant difference between the NSAIDs and placebo group (mean difference: 1.39, 95% CI: 0.32-2.46, P = .3). Data from individual studies also reflected the same trend. The Q statistic and I2 values were on higher side (I2 = 94.2, Q = 51.7, P distribution < .001), indicating that data were heterogeneous. The pooled results for MMSE score are presented in Table 3. The same was evident from the forest plot (Figure 3). The range of mean difference (0.20-2.07) is presented in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Result Summary for MMSE Score Obtained From Meta-analysis.

| Class | Study/subgroup | Placebo | Statin | Weight (%) | Mean Differenceb | 95% CI (Lower) | 95 % CI (Upper) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | ||||||

| Classical NSAIDs | De Jong et al 11 2008 | 2.4 | 3.60 | 23 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 20 | 14.91 | 0.100 | −1.93 | 2.13 |

| Pasqualetti et al, 17 2009 | 2.7 | 0.50 | 66 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 66 | 32.04 | 0.600 | 0.43 | 0.77 | |

| Rogers et al, 18 1993 | 13.4 | 4.40 | 14 | 0.9 | 4.8 | 14 | 7.54 | 12.500 | 9.09 | 15.91 | |

| Scharf et al, 19 1999 | 0.86 | 3.21 | 14 | −0.41 | 2.7 | 17 | 14.29 | 1.270 | −0.84 | 3.38 | |

| ADAPT, 20 2008 | −0.46 | 3.47 | 889 | −0.67 | 3.5 | 589 | 31.22 | 0.210 | −0.14 | 0.56 | |

| Total (95% CI) | 1006 | 706 | 100 | 1.39 | 0.32 | 2.46 | |||||

| Heterogenity | Q = 51.7 | P = .001 | I2 = 94.19 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale.

a Sensitivity: 0.20 to 2.07.

b Mean difference was calculated as placebo treatment.

Figure 3.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) forest plot.

Discussion

Current meta-analysis was designed to evaluate the hypothesis suggesting the role of classical NSAIDs in AD by analyzing results from RCTs. Meta-analysis was conducted for a total of 7 studies that met the inclusion conditions set for this systematic analysis. The evaluations were conducted on well-known cognitive parameters ADAS-cog and MMSE.

The ADAS-cog is generally used as an efficacy measure in clinical drug trials of AD. The MMSE 21 is a quick and easy measure of cognitive functioning that has been widely used in clinical evaluation and research involving patients with dementia.

Both the parameters for cognitive functions (ADAS-cog and MMSE) did not show significant advantage in favor of NSAIDs which was contrary to the results obtained from observational studies. 9 However, results obtained from this meta-analysis are consistent with the findings of ADAPT study that had largest sample size among studies included in the analysis. 20

Randomized trials included in this analysis were short term and exposure of NSAIDs for limited time period (<12 months) might have not been sufficient to demonstrate the protective effect against AD. Also, limited brain uptake of orally administered NSAIDs may be a potential reason for nonsignificant differences obtained between placebo and NSAIDs-treated groups of randomized trials. 22

Although, RCTs are regarded as a superior level of evidence in clinical research, small number of RCTs included in this study may not be sufficient to detect the publication bias by funnel plot. 23 Study results included in this analysis were heterogeneous in nature. However, random effects model was used to adjust for the combined estimate in meta-analysis. 24

We could not find any RCT published on this topic after 2009. Negative or null evidence results from previous trials may be a reason for not conducting trials on this topic. However, the findings from this meta-analysis suggest that there is still a strong need to conduct a long-term, large-scale RCTs with these cognitive parameters that can further help to extend the results observed in meta-analysis. Pooled results from such studies can further be evaluated to conclude the relation between AD and traditional NSAIDs therapy. The positive results if obtained however need to be further supplemented by studies evaluating relative benefit of COX-2 selective inhibitors over traditional NSAIDs. 25 In absence of such RCTs in present scenario, indirect treatment comparisons or mixed treatment comparisons may also help to arrive at more robust conclusions. 26

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Prem Prakash Gupta, Diwakar Jha, and Rishabh Pandey were involved in all aspects of study conduct, literature search, study selection, data extraction data interpretation, and manuscript composition. Sandeep was involved in manuscript composition and Vikesh Shrivastav was involved in the study as a statistician. All authors met ICMJE criteria and all those who fulfilled those criteria are listed as authors. All authors had access to the study data and made the final decision about where to present these data.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer’s disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 Census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsartsalis S, Panagopoulos PK, Mironidou-Tzouveleki M. Non-cholinergic pharmacotherapy approaches to Alzheimer’s disease: the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10(1):133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doody RS. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine: best practices. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(10 suppl 16):34–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoozemans JJ, Veerhuis R, Rozemuller JM, Eikelenboom P. Soothing the inflamed brain: effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on Alzheimer’s disease pathology. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10(1):57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holly MB, Donna MW. Are inflammatory profiles the key to personalized Alzheimer’s treatment. Neurodegen Dis Manage. 2013;3(4):343–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tony WC, Rogers J. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease—a brief review of the basic science and clinical literature. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(1):a006346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laura G, Ennio O, Gary W. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in Alzheimer’s disease: old and new mechanisms of action. J Neurochem. 2004;91(3):521–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. In’t Veld B. A, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(21):1515–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Etminan M, Gill S, Samii A. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on risk of Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br Med J. 2003;327(7407):128–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jaturapatporn D, Isaac MG, McCleery J, et al. Aspirin, steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;15(2):CD006378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Jong D, Jansen R, Hoefnagels W, et al. No effect of one-year treatment with indomethacin on Alzheimer’s disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(1):e1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Etminan M, Gill S, Samii A. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on risk of Alzheimer's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2003;327(7407):128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neyeloff JL, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB. Meta-analyses and Forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. General methods for Cochrane reviews: http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_9/9_5_2_identifying_and_measuring_heterogeneity.htm

- 15. Aisen PS, Schafer KA, Grundman M, et al. Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2819–2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hüll M, Bauer J. Treatment with the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug piroxicam-B-cyclodextrin in Alzheimer’s disease. Ninth Congress of the International Psychogeriatric. Association. 1999;107(2):15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pasqualetti P, Bonomini C, Dal Forno G, et al. A randomized controlled study on effects of ibuprofen on cognitive progression of Alzheimer's disease. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21(2):102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rogers J, Kirby LC, Hempelman SR, et al. Clinical trial of indomethacin in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43(8):1609–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scharf S, Mander A, Ugoni A, Vajda F, Christophidis N. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of diclofenac/misoprostol in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1999;53(1):197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. ADAPT Research Group, Martin BK, Szekely C, et al. Cognitive function over time in the Alzheimer's Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT): results of a randomized, controlled trial of naproxen and celecoxib. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(7):896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lehrer S. Nasal NSAIDs for Alzheimer's Disease [published online January 9, 2014]. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mavridis D, Salanti G. How to assess publication bias: funnel plot, trim-and-fill method and selection models. Evid Based Ment Health. 2014;17(1):30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cakała M, Strosznajder JB. [The role of cyclooxygenases in neurotoxicity of amyloid beta peptides in Alzheimer's disease]. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2010;44(1):65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR task force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: part 1. Value Health. 2011;14(4):417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]