Abstract

Errorless learning (EL) is an instructional procedure involving error reduction during learning. Errorless learning is mostly examined by counting correctly executed task steps or by rating them using a Task Performance Scale (TPS). Here, we explore the validity and reliability of a new assessment procedure, the core elements method (CEM), which rates essential building blocks of activities rather than individual steps. Task performance was assessed in 35 patients with Alzheimer’s dementia recruited from the Relearning methods on Daily Living task performance of persons with Dementia (REDALI-DEM) study using TPS and CEM independently. Results showed excellent interrater reliabilities for both measure methods (CEM: intraclass coefficient [ICC] = .85; TPS: ICC = .97). Also, both methods showed a high agreement (CEM: mean of measurement difference [MD] = −3.44, standard deviation [SD] = 14.72; TPS: MD = −0.41, SD = 7.89) and correlated highly (>.75). Based on these results, TPS and CEM are both valid for assessing task performance. However, since TPS is more complicated and time consuming, CEM may be the preferred method for future research projects.

Keywords: task performance analysis, errorless learning, dementia, activities of daily living

Dementia causes progressive loss of various cognitive functions, including memory, executive functioning, and language abilities. Also, loss of social skills and initiative are major problems that occur in dementia. This leads to an inability to function independently at home and perform daily activities, affecting quality of life. Dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), in particular, is responsible for high health-care costs and burdens patients and their primary carers. Cognitive rehabilitation (CR) programs and occupational therapy focus on maintaining quality of life, despite the deficits that are likely to progress over time. Cognitive rehabilitation interventions aim to increase the patients’ autonomy and decrease caregiver burden by exploiting compensatory and restorative strategies and may comprise adaptations of the environment, the use of external aids, and interventions to relearn specific skills. 1,2

One example of a potentially successful nonpharmacological intervention is errorless learning (EL). 3,4 The basic assumption of EL is that errors made during the acquisition phase of learning a task, may interfere with correct responses during the later retrieval of what is learned. Due to explicit memory deficits and self-monitoring problems, these errors are not recognized and corrected but may be consolidated in memory in an implicit, automatic way. 5 The prevention of errors during learning has been demonstrated to be a promising technique in the CR of patients with dementia, and its application in clinical practice involves a combination of teaching techniques aimed at reducing the amount of errors made during acquisition as much as possible. 3,6

Recently, EL has been increasingly used in teaching patients with dementia instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) using various outcome measurements. 6 To date, the assessment of IADL functioning in patients with dementia is mostly limited to informant-based IADL questionnaires. 7 -9 In a systematic review of dementia-specific informant questionnaires, 12 IADL questionnaires were rated on 8 psychometric properties. Information was lacking for many important measurement properties, such as the content validity, internal consistency, and reproducibility. 10 Another disadvantage is that these questionnaires mostly rely on informant’s view on IADL performance, which is not always reliable and accurate. 11 Furthermore, the aim of these questionnaires is to provide an overall view on daily life functioning for diagnostic reasons; therefore, these instruments do not provide information on the quality of performance of specific IADL. 10 Hence, there is a need for a more objective and quantitative measure of IADL functioning in patients with dementia. Performance-based assessment provides such an objective behavioral evaluation of functional skills by observing directly an individual enacting an IADL. One such example of a performance-based measure for IADL is the Functional Living Scale Assessment (FLSA) developed by Farina and colleagues. 12 Here, the quality of performance was derived from the level of assistance needed by the patient to carry out the task. These authors found a good interrater and a sufficient test–retest reliability and recommended this scale to use in a diagnostic setting and in rehabilitation. However, the FLSA consists of a preset areas of interest and items, limiting its use to these included tasks. Alternatively, automatic video-monitoring systems can be used to obtain a performance-based measure. 13 -15 Here, the amount of initiated and/or completed activities and duration of task completion are measured by an event monitoring system (EMS). Event monitoring system measures task performance by automatic computer-based video analysis. It is therefore presumed to be less time consuming for raters and more accurate and objective than rater-based IADL questionnaires or observations. Study results suggest that it is possible to quantitatively assess IADL functioning supported by an EMS and that even based on the extracted data, the participants could be classified in the groups (healthy controls, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer) with high accuracy. 13 Event monitoring system can thus contribute to diagnostic decision-making and serve as a measure for therapeutic evaluation in rehabilitation. One disadvantage of EMS is that it does not provide information about the quality of the individual steps performed as part of the task (but basically “checks” the order and duration of the task steps in an automatic manner).

Although FLSA and EMS are promising examples of performance-based measures, both methods have their limitations. One method that may overcome these problems is the Task Performance Scale (TPS). This entails the rating of individual task steps, which take into account both the accuracy and the order of these steps. The TPS can be used for any self-chosen activity of daily living independent of the study setting (eg, in the patient’s home environment, a rehabilitation setting, or in a nursing home). Task Performance Scale has been examined in patients with dementia in a study of Dechamps and colleagues 16 and was also investigated in adults with acquired brain injury. 17

In an ongoing randomized controlled trial (RCT), EL is compared to trial and error learning (TEL) in teaching patients with dementia 2 everyday life tasks. 18 Although each of the above-mentioned rating methods seemed adequate for determining the efficacy of EL, they have not been investigated on reliability and construct validity in a naturalistic setting such as peoples’ homes, while the patient is performing relevant daily life tasks. Therefore, in this study, the core elements method (CEM) is introduced for 2 reasons: (1) to assess task performance in both treatment arms of relevant everyday tasks at patients’ homes and (2) to divide tasks into structured steps that can be easily taught and repeated several times during training sessions in a standardized way. A core element is defined as a series of task steps that are grouped in a logical way. Tasks are a priori subdivided into core elements, which are used as building blocks to teach tasks on the one hand and are used for rating performance afterward.

The aim of this study was to explore the validity and reliability of CEM as an assessment tool for rating IADL task performance in patients with dementia. Therefore, the interrater reliability of CEM and TPS was analyzed and compared. Second, the concurrent validity of CEM in comparison to TPS was analyzed.

Methods

Participants and Task Selection

Participants were recruited from 6 outpatient memory centers from university hospitals in Germany. Inclusion criteria for all participants were (1) diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia or mixed type dementia; (2) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) between 14 and 24; (3) living at home; (4) carer available; and (5) at least moderate need for assistance in IADL as defined by the Interview for Deterioration in Daily Living Activities . 7 Patients who fulfilled these criteria were selected by psychiatrists and neurologists working in the participating study centers. The selection of tasks and the training sessions were performed by psychologists and occupational therapists and took place at patients’ homes. For the current validation study, we sampled the posttreatment evaluation videos of 35 patients who were enrolled in the RCT and had been allocated to the EL condition. The planned sample size for the EL condition in the RCT was 88 participants. The ethics committee of the Freiburg University approved the study. For more details, we refer to the study protocol of the REDALI-DEM study. 18

During a face-to-face interview with the patient and his or her caregiver, 2 tasks were selected from a catalogue containing 43 tasks that were preselected and described by the authors. Each task was divided into 4 to 5 core elements (see Table 1 for an example). It was important to select a task that (1) was relevant for the patient and (2) the patient was no longer able to perform independently but for which still some residual task performance was left. Therefore, a task was only selected when patients were able to successfully perform at least 1 but no more than 2 core elements of the task. Another task was selected if the patient failed these criteria. If none of the 43 preselected tasks were relevant or suitable for the patient, another task could be chosen and was added to the catalogue. For more details, we refer to the study protocol of the REDALI-Dem study. 18

Table 1.

Example of an Activity Divided Into Different Core Elements.

| Making a phone call | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Element | Get the Number | Dial the Number | Make Conversation and End Call | End Task |

| Possible steps |

|

|

|

|

Procedure

The REDALI-DEM study compared 2 instructional methods in teaching patients with dementia 2 daily life tasks, that is, EL and TEL. Performance of the 2 selected tasks was videotaped at baseline (t0), after the first intervention block at 11 weeks (t1), at follow-up 16 weeks after having completed the intervention (t2), and 26 weeks after having completed the intervention (t3, see Table 2). For further details we refer to the REDALI-DEM study protocol. 18

Table 2.

Intervention Scheme.

| Weeks | 0-2 | 3-10 | 11 | 16a | 19-20 | 26 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement | t0 | t1 | t2 | t3 | ||

| Intervention | 9 sessions | break | 2 refresher sessions | |||

aPrimary measurement time point.

Design

The 2 rating methods CEM and TPS were compared using a random sample of 70 EL evaluation videos at t2, coming from 35 patients with AD, each of whom had chosen 2 tasks to relearn. 18 There were no patients excluded for this article. Only EL evaluation videos were chosen because the aim of the current study was to examine the assessment capabilities of CEM and TPS as rating methods and not the training effects of EL on task performance. Importantly, the assessment procedure for the EL and TEL videos did not differ, which makes that the reliability results of the present study can be generalized to both procedures.

Rating with the CEM was taught to 14 independent raters in a 1-hour training. They were students from the University of Freiburg without a background in neuropsychology or knowledge of geriatrics. The to-be-rated videos were randomly allocated to 2 raters (from the group of 14 raters) immediately after videotaping at t2, resulting in each video being rated twice. The same rater could not rate the same video twice.

Another 2 independent raters were chosen to rate the evaluation videos using the TPS. 16 They were both neuropsychologists with clinical experience in the geriatric population and familiar with EL and with the TPS method. The 2 raters of the TPS method each rated all 70 t2-evaluation videos within a short period of time. The CEM and TPS ratings were performed by different raters to prevent for possible influences that could affect their ratings. For pragmatic reasons, CEM was scored by novices, and therefore they received a 1-hour training contrary to the raters of TPS who were already experienced with the TPS method.

Outcome Measures

Core Elements Method

The therapists were provided with a catalogue of daily tasks that were subdivided into core elements and illustrated with detailed descriptions (see Table 1 for an example). The core elements were used as a stepwise approach to teach patients the tasks they had chosen. The same catalogue with core elements was used for rating performance after the training had ended by independent raters. Before rating the videos, each of the 2 raters consulted the catalogue that after training could contain additional detailed notes provided by the therapists. An example of such a personalized detail might be that while the catalogue description for searching telephone numbers mentioned “Search for the number in the mobile phone or phonebook”, the therapists’ additional note might state “number is searched in a personal address book”. In some cases, the standard task was altered and tailored to individual routines of patients by adding or deleting specific steps, which nonetheless related to the task goal. An example of such a modified instruction is “talk into the telephone using the ‘speaker’ function”. The performance quality was rated on each core element using a 7-point scale for each task, (1 = not performed at all as trained by the therapist; 7 = performed exactly as trained by the therapist). To determine the performance quality, raters could consult the provided notes of the therapists.

For the sake of comparison with the TPS assessment method, a mean performance score of the individual ratings of core elements of each task was calculated and converted to a percentage (number of correctly performed elements as a proportion of the total number of elements in a task).

Task Performance Scale

For each task, the TPS-raters wrote a script consisting of a sequence of steps that led to the stated task goal (see Table 3 for a script example). These scripts were discussed, and consensus was reached between both raters about the necessary steps for each task and their logical order (ie, leading to the stated goal). The videos were then scored independently by the 2 raters using the following scores for each task step: (1) competent; (2) questionable/ineffective; and (3) deficit.

Table 3.

Example of a Task Script.

| Using a Telephone |

|---|

| Take the telephone |

| Look on the paper/telephone for the correct number |

| Dial the number/choose the right number |

| Make a conversation |

| Switch off the phone optional step: put the phone back |

| Optional step: talk into the phone using the “speaker” function |

Competent (score = 2)

The step was performed successfully and executed in the correct or logical order.

Questionable/ineffective (score = 1)

The step was not performed correctly or completely, steps that have already been performed were repeated, actions unrelated to the activity were performed, or hesitations were shown verbally (eg, by asking “is this correct?”) or physically (eg, wavering or faltering), or the step was not carried out in the correct order (eg, putting on shoes and coat to go shopping before writing a shopping list).

Deficit (score = 0)

This score designates the absence of a response or a reaction.

Optional steps (such as using the speaker function to talk into the phone) were only rated if performed. Since these steps were not necessary to reach the stated task goal, they were not rated as a deficit when a patient did not show them. Inevitably, this leads to various amounts of rated steps between participants performing the same activity. A mean performance score using the individual ratings of each task was calculated and converted to a percentage to be able to compare the tasks to each other and to CEM scores. Thus, the total score for each task was the number of correctly performed steps as a proportion of the total number of steps in that task.

Statistical Analyses

Interrater reliability analyses

An interrater reliability analysis using intraclass coefficient (ICC) was performed to determine the degree of consistency between the CEM raters and the TPS raters. The ICC will be high if there is little variation between the scores given to each item by raters of the same assessment method (CEM or TPS). Intraclass coefficient values between 0.4 and 0.75 represent reasonable to good reliability, and ICC values >0.75 represent excellent reliability. 19 As the ICC only demonstrates the overall agreement between raters, we examined potential absolute differences among the CEM raters and the TPS raters using Blant-Altman plots and 1 sample t test. 20 Here, the mean difference should not significantly differ from 0 to indicate interrater agreement.

Concurrent validity analyses

To examine the concurrent validity between CEM and TPS, Pearson correlations between the ratings of CEM and TPS were calculated. A high correlation suggests that the score of CEM ratings is highly related to the scores of TPS ratings. It also indicates that both methods are measuring the same construct.

Results

A total of 35 patient outcome videos (from 19 women and 16 men) were rated, resulting in 70 rated task performances (2 tasks per patient). Mean age of the patients was 81.0 years (standard deviation [SD] = 6.6). The mean MMSE score of these participants was 19.2 (SD = 4.7).

Interrater Reliability of the Core Elements Method

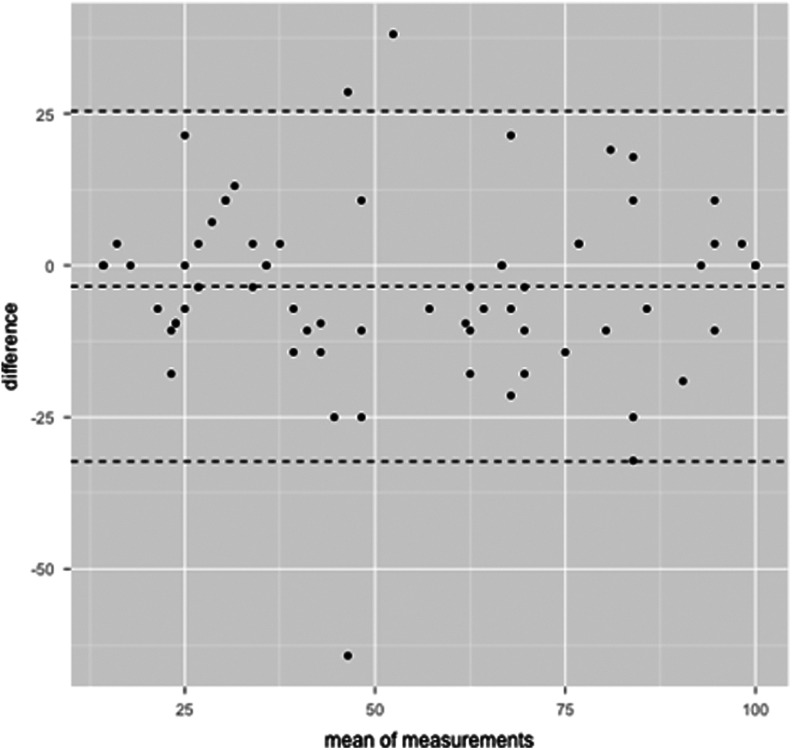

The CEM ratings resulted in an ICC of .85 with a 95% confidence interval from .77 to .90, F (69,70) = 12.28, P < .001. Figure 1 shows the Bland-Altman plot; the mean of the measurement difference (MD) between the CEM raters (MD = −3.44, SD = 14.72) did not differ significantly from 0, t(69) = −1.95, with a scoring range between 14.3 and 100.

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plot for the agreement in the ratings with the core elements method (CEM). Every point represents a data point, each assessed by the 2 measurements. The abscissa displays the mean of the 2 measurements. The ordinate displays the difference between the 2 measurements. The dotted line in the middle represents the absolute mean of the differences. The outer 2 dotted lines represent the mean ±1.96 times the standard deviation of the difference.

Interrater Reliability of the TPS

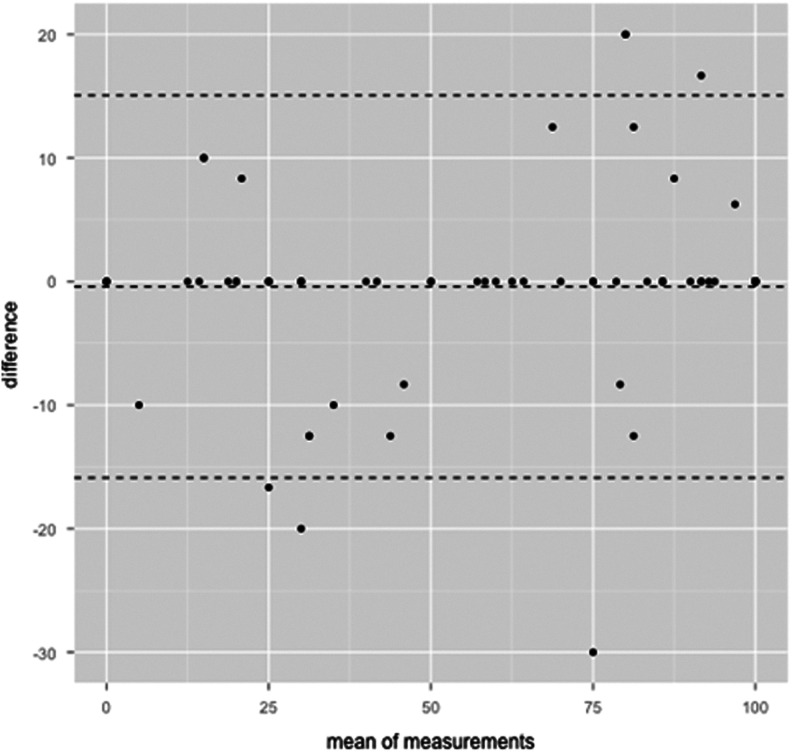

For TPS, the ICC was .97 (95% confidence interval: .95-.98, F (69,69) = 69.57, P < .001). Figure 2 shows the Bland-Altman plot of TPS ratings. The mean of the MD between the TPS raters (MD = −0.41, SD = 7.89) did not significantly differ from 0, t(69) = −0.44. The raters used the whole scoring range on the TPS (scores between 0 and 100).

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman plot for the agreement in the ratings with the Task Performance Scale (TPS) method. Every point represents a data point, each assessed by the 2 measurements. The abscissa displays the mean of the 2 measurements. The ordinate displays the difference between the 2 measurements. The dotted line in the middle represents the absolute mean of the differences. The outer 2 dotted lines represent the mean ±1.96 times the standard deviation of the difference.

Concurrent Validity of CEM and TPS

To examine whether both assessment methods resulted in similar ratings, Pearson correlations were computed between the TPS ratings and the CEM ratings (Table 4). All correlations were significant and higher than .75.

Table 4.

Pearson Correlation for All Groups of Raters.

| TPS 1 | TPS 2 | CEM 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPS 1 | |||

| TPS 2 | .97a | ||

| CEM 1 | .82a | .79a | |

| CEM 2 | .79a | .76a | .85a |

Abbreviations: CEM, core elements method; TPS, Task Performance Scale

a P < .001.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the reliability and validity of the newly developed CEM to asses task performance in patients with dementia. Therefore CEM was compared to the TPS, a rating method that was applied in previous studies examining task performance in patients with AD and brain injury. 16,17 The interrater reliabilities of CEM and TPS and their concurrent validities were analyzed.

The interrater reliabilities as reflected by the ICC values for both methods were excellent, although the confidence limits were wide, indicating that the sample mean could vary considerably around the true mean. However, additional Bland-Altman plots showed no significant differences in absolute scores given between the TPS raters and the CEM raters, indicating that raters agreed in their ratings within each method. The results showed high and significant correlations between both methods, strongly suggesting that the CEM ratings and TPS ratings are highly related to each other and that both methods are measuring the same construct. Furthermore, CEM and TPS raters used almost the full assessment range to evaluate the videos.

In line with these findings, Farina and colleagues 12 also found a high interrater and a sufficient test–retest reliability for their FLSA to assess IADL performance in patients with AD based on the degree of assistance needed to complete a task. Limitations of this study were that they used several standardized IADL tasks with standardized tools. Another disadvantage is that ratings by a trainer or rater are laborious and not always completely objective. Therefore, EMS has gained interest as a measure of task performance using a computer-based system. Although EMS is very promising and seems to be more objective than the FLSA, it can be used only for standardized tasks and in a standardized setting.

In conclusion, we suggest that CEM and TPS are more preferable than the above-mentioned assessment methods, since they can be used in natural settings and are flexible enough for examining individual performances of/and personalized tasks without compromising in agreement between raters. Furthermore, CEM and TPS also take the quality of the performance into account. There are several differences between CEM and TPS relevant to point out. First, the TPS method was performed by 2 experienced neuropsychologists. This is in contrast with the CEM method that was performed by psychology novices who were not specifically familiar with patients with dementia or EL and therefore received 1 hour of training. For TPS, scripts for each activity were made, and consensus about these scripts was reached before the actual rating. This contrasts with the CEM method where the raters received a catalogue with detailed task description and additional notes of the therapist beforehand. The TPS ratings were done over a short amount of time, where CEM ratings were made immediately after an evaluation measurement. Thus, with less skilled raters and no need for discussion to reach consensus about the task description (as in TPS), CEM succeeds to rate similarly as TPS. Furthermore, the core elements could also be used as building blocks to teach tasks and thereby supporting the therapists in their treatment adherence, although this latter has not been examined yet.

Limitations

A limitation of the present study is that raters exclusively applied either CEM or TPS. In future research, a crossover design is recommended in which the 2 methods are used by both groups of raters. In addition, comparisons of CEM and TPS ratings at different time points are required in order to determine the sensitivity to change in both methods. One could argue that it is a limitation that TPS and CEM were only studied in the EL group and not in the TEL group. Since the rating procedure is the same in both learning conditions (EL vs TEL), it is not expected that ratings in the TEL condition will lead to different results.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates assessment methods to rate everyday task performance in patients with dementia who were taught IADL with EL in clinical research. The CEM is recommended for assessing everyday task performance in clinical trials, because this method demonstrated sufficient variance, excellent interrater reliability, and high correlations with TPS, which is more complex and time consuming to use in clinical trials. Furthermore, core elements can be used to support therapists during training sessions as they serve as building blocks to teach tasks in a structured manner.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The REDALI-DEM study is funded by the German Research Foundation (Reference Number: HU 778/3-1). RK, DB, and MW are funded by the NutsOhra Foundation (grant #1301-019) and extended previous work funded by a grant from the Devon Foundation.

Reference

- 1. Viola LF, Nunes PV, Yassuda MS, et al. Effects of a multidisciplinary cognitive rehabilitation program for patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66(8):1395–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olazaran J, Reisberg B, Clare L, et al. Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of efficacy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30(2):161–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clare L, Jones RS. Errorless learning in the rehabilitation of memory impairment: a critical review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18(1):1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grandmaison E, Simard M. A critical review of memory stimulation programs in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15(2):130–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baddeley A, Wilson BA. When implicit learning fails: amnesia and the problem of error elimination. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32(1):53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Werd MM, Boelen D, Rikkert MG, Kessels RPC. Errorless learning of everyday tasks in people with dementia. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1177–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teunisse S, Derix MM. The interview for deterioration in daily living activities in dementia: agreement between primary and secondary caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(suppl 1):155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Desai AK, Grossberg GT, Sheth DN. Activities of daily living in patients with dementia: clinical relevance, methods of assessment and effects of treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(13):853–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sikkes SA, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Pijnenburg YA, et al. A new informant-based questionnaire for instrumental activities of daily living in dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(6):536–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sikkes SA, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Pijnenburg YA, Scheltens P, Uitdehaag BM. A systematic review of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scales in dementia: room for improvement. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jorm AF. The Informant Questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): a review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16(3):275–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Farina E, Fioravanti R, Pignatti R, et al. Functional living skills assessment: a standardized measure of high-order activities of daily living in patients with dementia. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46(1):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konig A, Crispim-Junior CF, Covella AG, et al. Ecological assessment of autonomy in instrumental activities of daily living in dementia patients by the means of an automatic video monitoring system. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Konig A, Crispim-Junior CF, Derreumaux A, et al. Validation of an automatic video monitoring system for the detection of instrumental activities of daily living in dementia patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44(2):675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robert PH, Konig A, Andrieu S, et al. Recommendations for ICT use in Alzheimer’s disease assessment: Monaco CTAD Expert Meeting. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(8):653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dechamps A, Fasotti L, Jungheim J, et al. Effects of different learning methods for instrumental activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia: a pilot study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26(4):273–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bertens D, Fasotti L, Boelen DH, Kessels RP. A randomized controlled trial on errorless learning in goal management training: study rationale and protocol. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Voigt-Radloff S, Leonhart R, Rikkert MO, Kessels R, Hüll M. Study protocol of the multi-site randomised controlled REDALI-DEM trial—the effects of structured relearning methods on daily living task performance of persons with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(2):135–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]