Abstract

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a young-onset neurodegenerative disorder characterized by declining language ability. The nonfluent/agrammatic variant of PPA (PPA-G) has the core features of agrammatism in language production and effortful, halting speech. As with other frontotemporal spectrum disorders, there is currently no cure for PPA, nor is it possible to slow the course of progression. The primary goal of treatment is therefore palliative in nature. However, there is a paucity of published information about strategies to make meaningful improvements to the quality of life of people with PPA, particularly in the early stages of the disease where any benefit could most be appreciated by the affected person. This report describes a range of strategies and adaptations designed to improve the quality of life of a person with early-stage PPA-G, based on my experience under the care of a multidisciplinary medical team.

Keywords: adaptation, frontotemporal degeneration, nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia, palliative care

Introduction

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a major clinical presentation of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and is characterized by declining language ability. 1,2 It is a young-onset neurodegenerative disorder, with an average age of onset of about 60 years, although it may begin in individuals with ages ranging from the 20s to 80s. Consensus criteria have been developed to classify PPA into 3 clinical subtypes based on specific speech and language features at relatively early stages of the disorder. 3 Nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA (PPA-G), also known as progressive nonfluent aphasia, has the core features of agrammatism in language production and effortful, halting speech, and at least one of these characteristics should be present for a clinical diagnosis. At least 2 of the following 3 other features should also be present: limited comprehension of syntactically complex sentences; spared single-word comprehension; or spared object knowledge. The essential diagnostic features of semantic variant PPA are anomia and single-word comprehension deficits. Logopenic variant PPA is identified by word retrieval and sentence repetition deficits. Other cognitive impairments are not apparent at first in people with PPA but problems may develop over time with working memory, mental planning, and dual tasking. 4 In the later stages of the disease, socially inappropriate behavior similar to that seen in people with behavioral variant frontotemporal degeneration (bv FTD) may emerge, 5 manifesting as apathy, repetitive behaviors, or disinhibition with poor insight and loss of empathy. Many people with PPA-G will also develop extrapyramidal motor problems similar to those seen in corticobasal syndrome or progressive supranuclear palsy. 1,2

As with other frontotemporal spectrum disorders, there is currently no cure for PPA, nor is it possible to slow the course of progression. The primary goal of treatment is therefore palliative in nature and seeks to improve the affected person’s quality of life. Although there are a few published descriptions of methods to enhance the well-being of people in the later stages of PPA (eg, ref 6), there is little available information about strategies to make meaningful improvements to the quality of life of people in the early stages of the disease. This report describes a multidisciplinary approach to adaptations designed to enhance the quality of life of a person in the early stages of PPA-G and is based on my first-hand experience. Whereas a piece this length would have been a day’s work during my career as a university professor, due to my loss of ability it now represents a significant effort and, with the support of my speech–language pathologists and medical team, I have written this report over the course of 5 months in sessions of 20 minutes or less.

Report

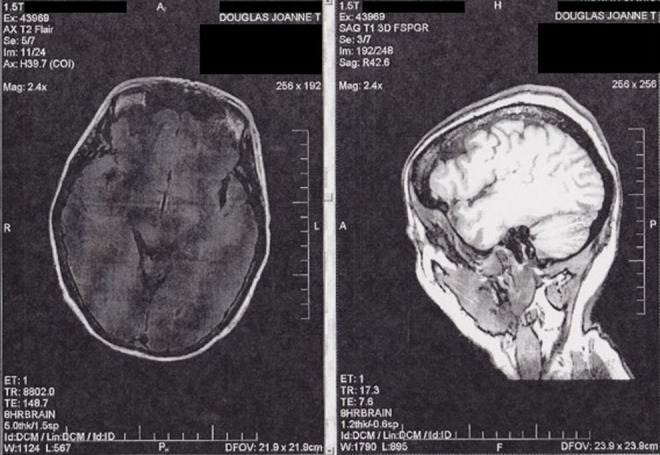

At the time I was diagnosed with PPA-G, I was 46 years old. I have no family history of frontotemporal spectrum disorders. My recent medical history had included 16 major surgeries requiring general anesthesia in a 38-month period and I had been treated for stage II breast cancer with radiation therapy. During this time, I was experiencing progressive difficulty with language that made it necessary for me to retire from my faculty position in an academic medical center. My speech had become increasingly effortful with occasional stuttering and I could no longer either read critically or write at a high level for more than about 30 minutes per day. My complicated health issues meant that I was already under the care of a team of brilliant doctors at the academic medical center where I worked, led by my radiation oncologist, palliative care physician, and internist, who continue to treat and support me. Suspecting a neurological basis for my progressive language difficulties, I was referred to a neighboring academic medical center where the chair of neurology directed me to a neurologist who had recently completed a fellowship in cognitive neurology and had been recruited to enhance their scientific program and clinical care in the area of FTD. At that time, structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed very subtle asymmetry in the left perisylvian area with mild biparietal atrophy, but normal frontal, anterior temporal, and hippocampal volume. I had also developed right-sided parkinsonism with tremors and gait imbalance. Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers ruled out an atypical presentation of pathologic Alzheimer’s disease. At my first consultation, approximately 2.5 years after the onset of my language difficulties, my neurologist made a clinical diagnosis of PPA-G, supported by imaging, based on the international consensus criteria for PPA. 3 In the 3 years since his diagnosis, I have been closely observed by my neurologist, with hour-long visits at intervals of 4 to 6 months, and the course of my progression is consistent with PPA-G. A structural MRI scan performed in May 2013, 3 years after the previous study, shows mild but definite progression of the left perisylvian atrophy and an area of atrophy in the left dorsolateral prefrontal region that was not as evident in 2010. Axial and sagittal slices from this MRI are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Axial and sagittal slices from structural magnetic resonance imaging scan showing left perisylvian atrophy and an area of atrophy in the left dorsolateral prefrontal region of the author's brain.

At the early stage of PPA at which I was diagnosed, the chief focus of treatment is to enhance quality of life by employing communication strategies targeted to the individual’s specific language impairments. During my initial consultation, my neurologist observed that I was speaking softly, although I had not noticed this reduced volume myself. Subsequent evaluation by a speech–language pathologist (SLP) showed that I spoke with an average vocal intensity of 59 decibels (dB). Therefore, I undertook a course of Lee Silverman voice treatment to increase vocal loudness. 7 The program focuses on a simple set of tasks designed to maximize phonatory and respiratory functions and is comprised of 1-hour sessions with a certified clinician on 4 consecutive days a week for 4 weeks with daily homework. After this intensive course, my average vocal intensity in conversational speech increased to 73 dB. By performing daily exercises, I have now maintained this volume for more than 2 years. The obvious result of my improved speech production is that it is easier for me to be understood, but an additional benefit is that speech is less exhausting and I now very rarely stutter.

My profession relies on the fluent and precise use of language in speaking, lecturing, and teaching; in reading, writing, and reviewing scientific articles and grants; and in designing and interpreting experiments. It was therefore very noticeable to me when these language-based activities became increasingly effortful, and it was apparent to others that my speech was halting and that I was closing my eyes to focus on my speech production. However, it was not easy to quantify this decline as I still performed well on most standard tests of speech and language function when I first consulted an SLP. My SLP was able to detect difficulties in the area of high-level cognitive–linguistic functions and designed a program of exercises employing functional compensatory strategy use to help with these deficits.

We have also been devising a number of strategies to address the particular challenges I am facing as my PPA-G progresses. From the onset, I have experienced a marked decline in my ability to speak fluently after I have spoken for a certain length of time (currently around 40 minutes, although this is continuing to decrease). It is not possible for me to regain fluent speech by continuing in conversation when it has started to slip, so I stop speaking at that point and spend time in restorative silence in order to recover. I also deliberately spend time in silence prior to important conversations. I find it helpful to consider that I have a daily “quota” of words available for use. As a consequence, I carefully prioritize and plan my speaking activities each day, with the goal of optimizing my ability to communicate when it is most needed. I also try to schedule my important activities for the late morning and early afternoon, which are the times of day when I am most functional. I have found other people to be understanding of this concept of a quota of words, and willing to accommodate my limitations in a way that might not have been achieved if I had simply said I was too tired to talk.

A further strategy to help maximize my functionality in speech is to make notes before important conversations, appointments, or meetings. I prepare a written outline of the key points I want to discuss and assemble some vocabulary relevant to the topic at hand. Rather than spend precious time and energy searching for the perfect word, I remind myself it is acceptable to use an adequate word. In certain situations, for example, when starting a conversation, I plan exactly what I want to say and then rehearse that sentence mentally before speaking it aloud. In this regard, I have prepared a stock speech informing people that I have PPA-G.

Another problem I have experienced from the onset of PPA-G is that background noise seems much louder and more intrusive, with every individual sound being overamplified. The result is overstimulating and hampers my ability to converse in social settings, such as coffee shops, restaurants, or parties, so I avoid these situations whenever possible. My preference is to entertain at my home, where I can manage the environment, but if eating at a restaurant is unavoidable, I try to minimize distraction by visiting during off-peak hours and sitting at a side table, facing the wall.

I have also encountered difficulties with writing since the onset of PPA-G. Just as with speech, I have a daily quota of words available for writing. When this quota is depleted, words begin to look strange and I start to wonder whether they are spelled correctly and if my sentences are grammatically correct—even when there are no errors. Therefore, I stop writing at that stage to avoid undoing whatever I have accomplished. I am currently able to write well for about 20 minutes, so I have needed to develop strategies to make the best possible use of this time. Therefore, I keep a list of things I need to write and a list of people I want to write to. I deliberately minimize the intellectual effort required in list making by quickly jotting down simple bullet points of items without regard to grammatical content. As such, these lists allow me to optimize my functional time without themselves subtracting from my daily quota of words available for good quality writing. I spend time planning what I intend to say and rehearsing some sentences in my head so that when I actually sit down to write I will be able to start straight away. When I am having trouble selecting the correct word, I now find it helpful to run through the choices by speaking aloud. If I am writing an important letter, I will start it one day and then review it the following day before sending it.

The progressive loss of language ability means that there is a continual process of devising, implementing, and refining strategies to adapt to the ongoing changes. As time has passed, I can no longer manage to have both a significant conversation and produce even a short piece of high-quality writing on the same day. Hence, I now find it necessary to prioritize my language activities on a daily basis. Accordingly, it is important to have realistic expectations of myself and set goals in keeping with my current level of ability.

Over time, my ability to write has been declining more rapidly than my ability to speak. At the recommendation of my neurologist, I have begun using Dragon NaturallySpeaking voice recognition software to improve my productivity. A major benefit is that I no longer have to spend time puzzling about spelling. If I am working on a longer piece, I now find it essential to begin with a very detailed outline to which I can add a few sentences at a time as my ability allows. When I have realized that I have exhausted my daily quota of words available for good-quality writing, I will make a very rough note of some words or ideas I could use in the next section, so that I will be ready to pick up where I left off. And in order to make the best possible use of my time, I now make a note of useful words or phrases as they come to mind during the day, either by jotting them down on paper or by recording a voice note on my smartphone.

In addition to the progressive loss of language, I am experiencing motor decline and have therefore been adapting to compensate. After my problems with gait imbalance resulted in a series of falls, my neurologist recommended the use of trekking poles with rubber balance tips. These have proven very beneficial, allowing me to keep an upright posture and walk at a brisk pace without falling. Six-monthly assessments by a physical therapist provide me with an individualized program of daily home exercises for strengthening, balance, and flexibility that evolves to meet my changing needs. An occupational therapist conducted an environmental evaluation of my home, making current and future recommendations for modifications tailored to my requirements, and demonstrating how to maneuver safely, particularly within the kitchen and bathroom.

Thus, a substantial part of my adaptation to early-stage PPA-G has involved strategies to manage my progressive language difficulties and specific physical symptoms. Additionally, I have followed general recommendations from my team of doctors who adopt a holistic approach, emphasizing the importance of eating well, maintaining social interactions, and exercising regularly to improve cognitive reserve. On top of these universally applicable guidelines, I have benefitted from the willingness of my palliative care doctor and other physicians to treat me as an individual and consider highly personalized ways to enrich my quality of life, for example, by making it possible for me to have continued access to the university medical library after retirement and by encouraging me to write about my experience. Most importantly, the adjustment to living with a progressively debilitating neurological condition that will ultimately lead to my death has a spiritual dimension in which I derive strength from my faith and receive support from my clergy and physicians. Accordingly, my beliefs and personal values have been respected in the approach to my treatment from the onset and are likewise reflected in both the advance planning for care as I become increasingly dependent and my end-of-life decisions.

Discussion

Primary progressive aphasia typically affects people in what would otherwise have been the most productive years of their lives. It is being recognized with increasing frequency and with a trend to earlier diagnosis. In the absence of a cure or a way to slow the course of progression, treatment for PPA is currently palliative from the onset. However, there is still a paucity of available information about ways to improve the quality of life of people with PPA, particularly in the early stage of the disease.

In this report, I have described a range of strategies that have been beneficial in enhancing my quality of life since I received a clinical diagnosis of PPA-G, which is supported by imaging. I have been under the care of a multidisciplinary medical team, comprising a neurologist, palliative care doctor, internists, and other physicians, with the continued involvement of my radiation oncologist, and supported as necessary by speech–language pathologists, a physical therapist, an occupational therapist, and a dietician. I realize that I am fortunate to be receiving an exceptional level of coordinated, multidisciplinary care. Nonetheless, my experience serves as a paradigm for the management of patients with early PPA. The major focus has been to develop and implement strategies targeted to my specific difficulties with language at this early stage of disease. To this end, I have employed approaches designed to compensate for my declining ability to speak and write, thereby allowing me to achieve optimal communication at the times when it is most needed. The achievement of meaningful differences in the ability to communicate is universally relevant to improving the quality of life in people with early-stage PPA. Moreover, the clinical phase during which such benefits could be appreciated may last a number of years, as people whose professions depend on the use of language (eg, writers and teachers) can be aware of difficulties at a very early stage of the disease. 8

In addition to supporting my declining language ability, my adaptation to early-stage PPA-G has encompassed all other aspects of the condition, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual. My quality of life has benefited from a wide range of personalized strategies that continually evolve as the disease progresses. It is apparent that it is in the early stage of PPA, before the onset of generalized cognitive or behavioral problems, that any intervention could most be appreciated by the affected person. This highlights the need for the early and accurate diagnosis of PPA. The ability to make an early diagnosis would be supported by clinical language tests with the sensitivity to detect deficits in individuals with high baseline function, who may perform well in currently available tests even though they are no longer able to attain their former levels of ability. In the future, it is to be hoped that clinical diagnosis will be enhanced by use of neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid or plasma biomarkers, thereby allowing identification of the underlying pathology and ultimately leading to etiology-specific treatments. 9

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. William T. Hu, Dr. Elizabeth Kvale, Angel A. Rivera, and Dr. Lisa B. Rivera for their critical review of the manuscript and helpful comments; Leslie H. Harper, CCC-SLP, and Laura E. Royal, CCC-SLP, for their help, support and review of the sections concerning speech–language pathology; Dr. Analia Castiglioni, Dr. Jennifer F. De Los Santos, Dr. William T. Hu, and Dr. Elizabeth Kvale for their wisdom, insight, help, support, and encouragement; Andrea J. Kippels, NP, and Terri Sinquefield, RN, for help, support, and encouragement; Sharon Denny and the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration for support and encouragement; and the Department of Medicine, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care at The University of Alabama at Birmingham for granting me a voluntary appointment.

Footnotes

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(4):425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grossman M. The non-fluent/agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(6):545–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Libon DJ, Xie SX, Wang X, et al. Neuropsychological decline in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a longitudinal analysis. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):337–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banks SJ, Weintraub S. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21(2):133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hall GR, Shapira J, Gallagher MJ, Denny SS. Managing differences: care of the person with frontotemporal degeneration. Gerontol Nurs. 2013;39(3):10–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramig LO, Bonitati CM, Lemke JH, Horii Y. Voice treatment for patients with Parkinson disease: development of an approach and preliminary efficacy data. J Med Speech Lang Pathol. 1994;2:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sapolsky D, Domoto-Reilly K, Negreira A, Brickhouse M, McGinnis S, Dickerson BC. Monitoring progression of primary progressive aphasia: current approaches and future directions. Neurodegen Dis Manage. 2011;1(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hu WT, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM. Biomarkers in frontotemporal lobar degenerations—progress and challenges. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95(4):636–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]