Abstract

Education is associated with longer life and less disability. Living longer increases risks of cognitive impairment, often producing disability. We examined associations among education, disability, and life expectancy for people with cognitive impairment, following a 1992 cohort ages 55+ for 23 063 person-years (Panel Study of Income Dynamics, n = 2165). We estimated monthly probabilities of disability and death for 7 education levels, adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, and cognitive status. We used the probabilities to simulate populations with age-specific cognitive impairment incidence and monthly disability status through death. For those with cognitive impairment, education was associated with longer life and less disability. Among them, college-educated white women lived 3.2 more years than those with <8 years education, disabled 24.4% of life from age 55 compared with 36.7% (P < .0001). Increasing education will lengthen lives. Living longer, more people will have cognitive impairment. Education may limit their risk of disability and its duration.

Keywords: active life expectancy, Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive health, dementia, disability, education, morbidity compression, panel study, older people

Individuals with cognitive impairment, including impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease or related disorders, can age more successfully and in better physical health when they are not seriously disabled by the disease itself or by physical problems that can disable anyone. The challenges that their families or other supporters experience are likely to be less severe when these individuals remain free of disabilities other than cognitive impairment, thus reducing the risk of caregiver burnout and institutionalization. 1 –6 Educational attainment increased throughout the last century. 7 That increase may alter trends in life expectancy and disability. 8 –10 It may also affect the incidence or progression of cognitive impairment, including the number of people whose cognitive impairment is so substantial that they become unable to do simple activities of daily living (ADLs). 11 –14 Thus, it is useful to examine whether having more education is associated with less disability among people with cognitive impairment.

Pathways That May Link Education With Cognitive Function and Disability

Multiple pathways may link education, cognitive function, and disability. 9,15 –21 There is increasing evidence that diabetes and hypertension increase the risk of cognitive decline and dementia. 22 Although the ability of medical care to reduce risks of cognitive impairment remains uncertain, controlling these conditions may have that effect, in part by reducing vascular damage that contributes to cognitive decline. 22 People with more education have better access to health care. 16 –19,23,24 That may help control vascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension, 21,23,25 reducing the risk of cognitive decline, delaying its development, or limiting its severity. 22 People with more education tend to have greater health literacy, 16,17,19,23 helping them manage chronic diseases that are risk factors for both cognitive decline and disability.

People with more education are also more likely than others to consider long-term effects of their health-related decisions 16 –19,24 and to believe that they have “self-efficacy,” the ability to influence their health through their decisions and actions. 16 –19,24,26 They are less likely to smoke; they exercise more, have healthier diets, and have higher high-density lipoprotein levels than those with less education. 16,19,21,25 There is evidence that this reduces the development or severity of vascular dementia and possibly of Alzheimer’s disease. 22,27 –32 Cognitive reserve developed through education may also promote cognitive health. Although a large proportion of older individuals have evidence of brain pathology, having developed reserve cognitive capacity through education may limit its effects for everyday living. 11,14

However, little research has examined associations between education and the risk and duration of disability associated with cognitive impairment. Active life expectancy, a central measure of population health, allows us to examine these associations. 10,33,34 Active life expectancy measures both life expectancy from a given age and the proportions of remaining life with and without disability, 10,33 –36 where disability is often measured by a person’s ability to do ADLs such as dressing, bathing, eating, or using the toilet. The World Health Organization, the United States, and governments throughout the world use active life expectancy to anticipate needs for policies, programs, services, and resources that accompany changes in life expectancy and the prevalence of disability. 10,33 –39

Many studies have examined associations between education and life expectancy. A smaller number have studied the association between education and active life expectancy. 10,34,39 Only a few of them have addressed cognitive status. Studies have found that older women and men with more education live substantially longer and have less disability than those with less education. 8,9,40 –45 Three recent studies also found that people with more education lived longer than others, with less cognitive impairment. 12,13,46

Our study differs from previous research by focusing on ADL disability among individuals who develop cognitive impairment rather than on cognitive impairment as the outcome. People who do not become disabled in ADLs are better able to cope with the challenges of aging. Avoiding ADL disability contributes to quality of life and reduces costs of caregiving, long-term care, and special equipment. Since advanced cognitive impairment involves ADL disability by definition, 47 those with cognitive impairment who do not have ADL disability have avoided or delayed the most serious stages of dementia. It would be useful to know whether having more education is associated with that positive outcome.

Study Objective and Hypothesis

We examined associations between educational attainment and active life expectancy, with a focus on people who develop cognitive impairment. Based on the pathways described previously, our hypothesis was that among older people with cognitive impairment, those with more education would live longer than those with less education. We also expected that despite living longer, those with more education would have less disability than those with less education.

Methods

Data

We used data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), the longest running panel survey in the United States. 48 The PSID is a useful resource for studying health, aging, and life course processes such as disability. 48 We followed a cohort aged 55 and older in 1992 through 2009 or until death (n = 2165; 23 063 person-years). The PSID interviewed individuals and families beginning in 1968, annually through 1997, and then biennially. We used data from before 1992 as needed to identify educational attainment. Because life expectancy and the risks of disability may differ among ethnicities, we wanted to estimate active life expectancy by ethnicity. 8,10,38 Sixty-six individuals reported ethnicities other than African American or non-Hispanic white (hereafter referred to as white). We excluded those observations. We provided separate results for African Americans and whites.

The analytic data that we used to estimate probabilities of disability and death had 1 observation for each interval in the longitudinal data, where an interval was a pair of observations for a given individual from successive surveys or from a survey followed by death. The PSID identified death dates using the National Death Index (NDI). The National Center for Health Statistics compiles the NDI from state Vital Records. When a decedent’s information does match an NDI record, the PSID uses death information provided by the family. 48 Each individual contributed an average of 7 intervals to the analytic data, which had 15 078 observations. Combining information about disability and death transitions at all ages from 55 through 109 enabled us to calculate probabilities for those transitions representing people age 55 and older.

The PSID’s questions about ADL disability focused on individuals that the PSID has identified since 1968 as household “heads” and “wives.” The latter include cohabiters. Only 35 individuals aged 55 or older in the households of the analytic sample were not “heads” or “wives.” Those family members were not asked about diagnoses of cognitive impairment and could not be included in this research. With that exception, the data were nationally representative of African Americans and whites aged 55 and older living in the community.

Dependent Variable

Consistent with previous research, we focused on the ability to do ADLs: bathing, eating, dressing, getting into or out of a bed or chair, walking, getting around outside, and getting to and using the toilet. Consistent with other nationally representative surveys, participants were asked if they had “any difficulty” doing each activity “by yourself and without special equipment” and to report only difficulties that were “because of a health or physical problem.” 48 –51 Those reporting 1 or more ADL impairments were considered disabled. We linked responses to the month of each measurement and thus could estimate monthly disability transition probabilities.

Measuring Cognitive Impairment

The PSID measured cognitive health 7 times, in 1990 and in all waves beginning with 1999. In all waves beginning in 1999, it asked, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have permanent loss of memory or mental ability?” Analogous questions are phrased similarly in other national health surveys. 52 –54 The PSID told interviewers, “we mean a diagnosis by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other mental health professional of loss of memory or mental abilities.” The PSID stressed that it was not interested in diagnoses made by the participant or by others who were not health professionals. The question did not specifically ask about diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease or related disorders. We therefore use the phrase “cognitive impairment” to refer to positive responses to this question rather than the word “dementia.” The survey also asked how long the participant had this condition or in some years how old the participant was when diagnosed. We used that information to identify individuals who were cognitively impaired before 1999. Proxy respondents represented individuals who were too cognitively impaired to answer the question.

In 1990, the PSID asked participants whether they had “trouble with thinking, concentrating, or memory.” We took affirmative responses to that question to indicate cognitive impairment. Among those who did not report memory loss in 1990, 347 died before the 1999 survey, with mean age of 78.5 at death (standard deviation [SD] 8.9). Some of these individuals may have become cognitively impaired, misclassified in our data as unimpaired for a portion of the time before death (mean survival 3.9 years, SD 1.5). Based on the age-specific incidence rates for cognitive impairment described subsequently, it is likely that about 35 became cognitively impaired (95% confidence interval [CI] 27-44). We performed a sensitivity analysis, conducting microsimulations excluding intervals for the 347 individuals, 5.9% of all intervals in the analysis. Results did not differ meaningfully from those we present. As with disability, we assigned a value for cognitive impairment in the analytic data (0/1) for the year and month of each interview, including the retrospective assignments described previously.

Of all intervals identifying cognitively impaired individuals, 94.1% were reports of physician diagnoses. Among women, 7.9% reported cognitive impairment, represented by 896 intervals. Among men, 6% did so with 436 intervals.

Age-Specific Cognitive Impairment Incidence in the Microsimulations

Although microsimulation is a well-established method for estimating life course effects of disease, researchers have typically measured effects for diseases such as diabetes that are assumed to be present at a baseline age. 43 Cognitive impairment is rare at younger old ages, with exponential incidence growth throughout older life. 55 We developed an approach in which the simulated population developed cognitive impairment at the same age-specific rate as the US population. We estimated the age-specific incidence of cognitive impairment in the US population using incidence rates for “any dementia” from studies that were specifically designed to identify them. The data were available for 5-year intervals beginning at age 65. 56 To obtain the specific incidence rate for each year of age, we used these data to estimate an exponential regression model: ln(y) = 37.58052 − 1.76715(age) + 0.02308(age 2 ) − 0.0009345(age 3 ). This equation provided an excellent fit to the published data, R2 = .98.

It is not clearly established whether cognitive impairment incidence differs between women and men or between African Americans and whites. 57 –59 It is often suggested that men have a lower lifetime dementia risk, possibly due to women’s longer lives. We adjusted the estimates from the exponential regression model, reducing the rates 5% for men and increasing them 5% for women, to produce simulated populations reflecting published lifetime rates of cognitive impairment, about 20% for women and 11% for men. 57 Given uncertainty in the research literature about differences in rates of cognitive impairment between African Americans and whites, 57 we used the same rates for both groups.

Measuring Educational Attainment

The models included 7 levels of education: less than 8 years, completion of grade 8, completion of grades 9 through 12 without a high school diploma, high school graduation, some education after high school, a 4-year college degree, or education beyond the college degree. We first examined effects of these levels by estimating a model with a dummy variable representing each level. The results indicated a linear gradient of risk of each transition: becoming disabled (R2 .99), recovering from disability (R2 .93), dying when not disabled (R2 .99), and dying when disabled (R2 .92). There was no evidence of threshold or ceiling effects for education. We therefore estimated a final model with education entered as a single categorical variable with 7 levels, where the estimate for each transition type represented the change in risk associated with each additional level. We illustrate education effects by comparing results for those with a 4-year college degree to the results for those with less than 8 years of education.

Control Variables

The models included covariates associated with active life expectancy: age, gender, and ethnicity. All studies have found that disability increases with age. 8,37,45,60 Almost all studies have found that women live longer than men, with more time disabled. 8,41,45,50 Most researchers have found that African Americans have shorter life expectancy and more disability than whites. 8,38,41,61 We examined multicollinearity among these variables using the variance tolerance test. Values <.3 typically suggest that multicollinearity may affect an analysis. The smallest value for this test was .57, suggesting that multicollinearity was not an issue for this research.

Parameterization of age

Most related research has modeled age in years. Our research suggested that doing so inadequately represented age effects. We evaluated a variety of ways to model age effects, including the addition of quadratic and higher order age terms as well as spline functions to represent changing risks of disability and death throughout the older life course. We used the likelihood ratio test to evaluate the models. We also conducted a microsimulation with the parameters estimated by each model and compared the proportion of simulated individuals who survived to advanced ages to national estimates. Our final model represented increasing risks of disability and death with increasing age as well as an accelerating rate of that increase, and particularly greater risks beginning at age 85. The model representing that risk profile was age + age 2 + age85+ + (age85+ × age), where age 85+ is a dummy variable equal to 1 when age ≥85, otherwise 0. The addition of the quadratic term was statistically significant (P < .001) as was the addition of the spline knot at age 85, which is defined by age85+ + (age85+ × age). An additional interaction that extended the spline at age 85 to the age 2 term did not improve the model fit and was not retained.

Analytical Approach

Discrete-time Markov chains

We used a well-established maximum likelihood procedure to estimate a multinomial logistic regression model in which the dependent variable could have 1 of the 3 values, each representing a disability “state”: not disabled (no ADL limitations), disabled (1 or more ADL limitations), or dead. 10,37,45,46,62 –65 This model generated transition probabilities for each month of life. The probability for a given transition in a given month was conditional on current disability status, cognitive impairment status, age, education, gender, and ethnicity. We estimated a single equation representing women and men and both ethnic groups using a single analytic data set. Likelihood ratio tests comparing the single-equation model to separate analyses for each of the groups did not indicate a better fit to the data for separate equations. The equation included dummy variables indicating the groups defined by gender and ethnicity, which activated the probabilities specific to a given group for the simulation of its population.

Accounting for repeated measures

Researchers using these methods have not typically accounted for repeated measures on individuals, which are known to artificially reduce standard errors. 66 To account for this, we estimated a model with a γ distributed random effect. 67 The γ distribution is appropriate for phenomena with gradual risk change, such as the risk of disability throughout adult life. Such models provide more appropriate variance estimates than more standard approaches. The model confirmed that most covariates were statistically significant at P < .001. We adjusted the CIs used in the microsimulations to reflect larger variance estimates from the random effect model, providing more conservative (ie, wider) CIs for the microsimulation results.

Microsimulation

We used the transition probabilities and their standard errors to conduct microsimulations, creating 1 000 000 simulated individual lives for each group we studied. 45,62 For example, if a person had ADL value i and covariate values Xt in month t, the model generated the 3 transition probabilities, pi1(t + 1), pi2(t + 1), pi3(t + 1), corresponding to the possible states in the next month. Regardless of whether an individual was disabled or nondisabled in a given month, but conditional on that status, in the following month she or he could be nondisabled, disabled, or dead. Each transition had a probability that was specific to the individual’s age and other characteristics, which we estimated using the PSID data and the modeling strategy described previously. For each month of the microsimulation, we mapped these probabilities onto regions of the 0,1 interval: for example, region 1 was the interval from 0 to pi1(t + 1) and region 2 from pi1(t + 1) to [pi1(t + 1) + pi2(t + 1)]. Next, we drew a computer-generated random number between 0 and 1 and assigned the disability status for the next month corresponding to the region containing the random number value. We repeated this process until each individual died. Thus, each individual in the simulation was known to be disabled or not disabled in each month from age 55 to death, resulting from a process using probabilities that reflected the lives of a nationally representative sample of African Americans and whites age 55 and older living in the community. 43 –45,50,62

We created these monthly functional status histories for 8 groups of women and 8 groups of men, defined by cognitive impairment status, educational attainment, gender, and ethnicity. The proportion of disabled individuals in the baseline population of each microsimulation matched the proportion of the US population aged 55 to 60 living in the community with the same combination of education, gender, and ethnicity. We identified these proportions through weighted analysis of the PSID. Cognitive impairment is rare at age 55. We therefore did not include cognitive impairment when identifying these proportions.

We applied the age-specific cognitive impairment incidence rates to the surviving population in each year of each simulation, separately for those with and without disability in that year. When a simulated individual became cognitively impaired as a result of applying the age-specific incidence rate, she or he was cognitively impaired throughout remaining life.

Lifetime trajectories of disability-free and disabled life

Consistent with previous research using these methods, we treated the data from the microsimulations as longitudinal survey data for completed cohorts, those in which all individuals had died. Life expectancy for each simulated population was the average age at death. We also calculated the age of first disability and several measures for spells of permanent disability ending in death: the percentage of the group that had such a spell, the average age of its onset, and the average years of permanent disability.

Estimating variation

We estimated standard errors for the microsimulation results using the bootstrap method to account for Monte Carlo variation and parameter uncertainty. To do so, we repeated the simulation for each population group 1000 times. For each repetition, we drew a random value for each covariate from the distribution represented by its CI, which we adjusted as described previously to account for repeated measures. The 95% CI for each measure was the interval from the 2.5th percentile to the 97.5th percentile of the 1000 results. 50 We conducted the study with the SAS IML programming language. 43,50,68

Results

Sample Characteristics

The mean baseline age was 67.9 years (SD 8.4). Women were 60.6% of the unweighted baseline sample. The PSID over-samples African Americans, who were 28.6% of the unweighted baseline sample; in a weighted analysis that accounted for the survey design, African Americans were 8.8% of the baseline sample (95% CI, CI 7.6%-9.9%). In the education categories, 15.4% had less than 8 years of education, 8.4% completed the eighth grade, 18.1% ninth grade or more without completing high school, 34.9% graduated from high school, 10.7% had some additional education after high school without a college degree, 6.6% completed a 4-year college degree, and 5.9% had education beyond the 4-year degree. Among the 15 078 disability transitions, 8989 remained nondisabled (ie, a “transition” from being nondisabled at the time of a given interview to being nondisabled at the time of the following interview), 2995 remained disabled, 1246 became disabled, 925 recovered from disability, 403 died when not disabled, and 520 died when disabled. The average period between each pair of measured transitions was 17.1 months (SD 8.9).

Model of Functional Status Transitions

Table 1 shows the estimated parameters and variance-adjusted 95% CIs for the model of functional status transitions, by type of disability transition. The upper panel shows the parameters for becoming disabled and recovering from disability. The lower panel shows the parameters for dying when not disabled and dying when disabled. Taken together, the parameters express probabilities predicting disability transitions and death in any given month. Exponentiating each coefficient provides its odds ratio. For example, the odds ratio for becoming disabled for people with cognitive impairment is e0.479 = 1.61, indicating that they have 61% greater odds than people without cognitive impairment of becoming disabled in a given month. The odds ratio for recovering from disability is 1.03, indicating 3% greater odds of recovery for those with cognitive impairment. The combined effect of these covariates is much more disability for those with cognitive impairment. The odds ratio for becoming disabled for education is 0.84, indicating that each additional level of education is associated with 16% lower odds of becoming disabled in a given month. The implications of the probabilities for disability and death are best expressed in the microsimulation results described in the sections that follow. They represent the combined effects of all of the probabilities and their standard errors.

Table 1.

Estimated Parameters and 95% Confidence Intervals Representing Probabilities of Disability Transitions and Death, Ages 55 and Older, 1992 to 2009 Panel Study of Income Dynamics.a

| Becoming Disabled | Recovering from Disability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | LB | UB | Estimate | LB | UB | |

| Age in years (55-109) | 1.139 | 1.064 | 1.213 | −2.824 | −2.871 | −2.777 |

| Age 2 | 3.997 | 3.765 | 4.229 | −2.411 | −2.619 | −2.204 |

| Age 85+ | −1.608 | −1.647 | −1.569 | 0.485 | 0.465 | 0.504 |

| Age 85+ × age | 5.757 | 5.624 | 5.891 | −1.816 | −1.971 | −1.661 |

| Female | 0.149 | −0.052 | 0.350 | −0.083 | −0.111 | −0.055 |

| Cognitive impairment | 0.479 | 0.467 | 0.490 | 0.032 | 0.030 | 0.034 |

| African American | 0.343 | 0.336 | 0.351 | −0.029 | −0.033 | −0.025 |

| Education, 7 levels | −0.173 | −0.175 | −0.171 | −0.027 | −0.029 | −0.025 |

| Constant | −4.819 | −4.838 | −4.799 | −3.209 | −3.231 | −3.187 |

| Dying When Not Disabled | Dying When Disabled | |||||

| Estimate | LB | UB | Estimate | LB | UB | |

| Age years (55-109) | 10.862 | 10.817 | 10.908 | 5.575 | 5.541 | 5.609 |

| Age 2 | 0.218 | 0.075 | 0.361 | 0.549 | 0.446 | 0.653 |

| Age 85+ | −0.857 | −0.903 | −0.812 | −1.849 | −1.957 | −1.740 |

| Age 85+ × age | 1.887 | 1.717 | 2.056 | 5.556 | 5.121 | 5.992 |

| Female | −0.316 | −0.328 | −0.303 | −0.439 | −0.449 | −0.430 |

| Cognitive impairment | −5.106 | −5.112 | −5.099 | −0.222 | −0.223 | −0.220 |

| African American | −0.021 | −0.021 | −0.020 | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.013 |

| Education, 7 levels | −0.152 | −0.154 | −0.149 | −0.059 | −0.059 | −0.058 |

| Constant | −7.912 | −7.917 | −7.908 | −5.856 | −5.868 | −5.844 |

Abbreviations: LB, lower bound; UB, upper bound.

aResults of a multinomial logistic Markov model; data source 1992 to 2009 Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID); lower bound of the 95% confidence interval; data represent non-Hispanic whites (reference category) and African Americans; age 85+, female, cognitive problem, African American coded 0/1; age 85+ × age creates a spline knot at age 85; n = 2165; analytic sample = 15 078 transitions.

Active Life Expectancy

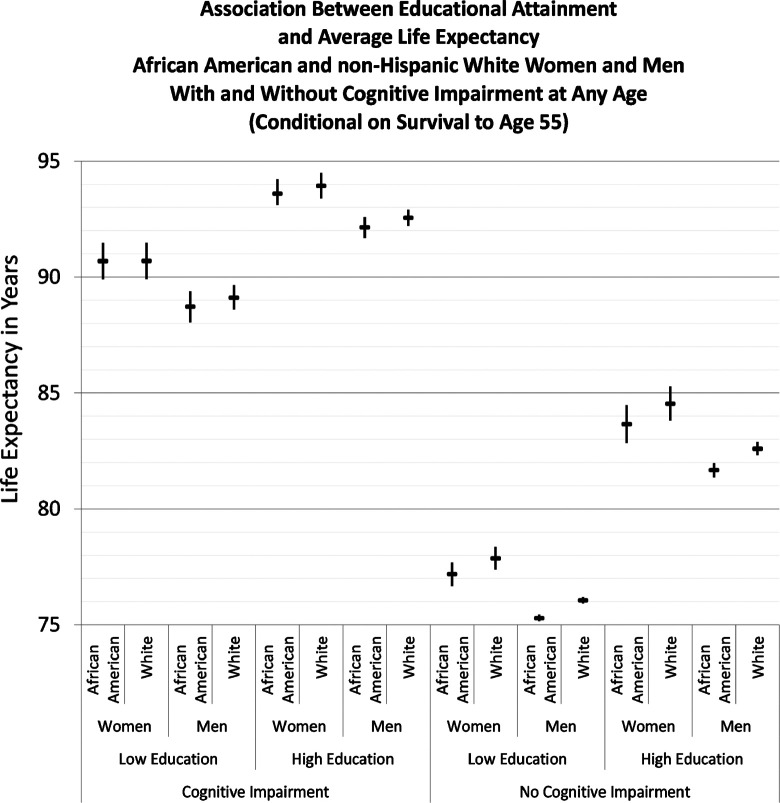

Figure 1 shows average life expectancy, represented by wide horizontal lines, for those with and without cognitive impairment. The thin vertical lines indicate the CIs. Life expectancy was substantially greater for those who developed cognitive impairment than for others. This is an expected result as people who live to older age have higher risks of developing cognitive impairment. In all groups of cognitively impaired individuals, those with more education had longer life expectancy than those with less education; statistically significant differences are shown by CIs that do not overlap. For example, among African American women who developed cognitive impairment, those with high education had a life expectancy of 93.6 years (CI 93.1-94.2) compared with 90.7 years (CI 89.9-91.3) for those with low education. Weighting the results in Figure 1 for the proportions of the population with and without cognitive impairment at each education level resulted in summary estimates that closely approximated the US Census Bureau’s estimates of life expectancy from age 60. The life expectancy estimates for those who developed cognitive impairment were consistent with epidemiological studies of persons with dementia. 55

Figure 1.

Data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1992 to 2009. Horizontal bars indicate point estimates for remaining life expectancy at age 55; vertical lines identify the 95% confidence intervals estimated from 1000 bootstrap microsimulation samples for each population group; bootstrap sampling accounted for parameter uncertainty and Monte Carlo variation; high education = college graduate; low education = grades 0 through 7.

Table 2 shows the percentage of the population that developed cognitive impairment at any age, the mean age of onset. and the mean years lived with cognitive impairment. The mean onset age, about 83, was similar for women and men. In every group defined by gender and ethnicity, those with more education lived more years with cognitive impairment. For example, for African American women with high education, the mean number of years lived with cognitive impairment was 10.1 (CI 9.6-10.7), compared to 8.0 (CI 7.6-8.3) for those with low education. A substantially lower proportion of African American and white men had cognitive impairment at any age than women. African American and white women lived more years with cognitive impairment than men.

Table 2.

Percent of Simulated Population With Cognitive Impairment at Any Age, Mean Age of Onset, and Mean Years With Cognitive Impairment.a

| Cognitive Impairment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Years With Cognitive Impairment | |||||

| Education | % With Cognitive Impairment At Any Ageb | Mean Age of Onsetb | Years | LB | UB |

| Women | |||||

| African American | |||||

| Low | 19.0 | 82.7 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 8.3 |

| High | 19.9 | 83.5 | 10.1 | 9.6 | 10.7 |

| White non-Hispanic | |||||

| Low | 19.2 | 82.8 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 8.5 |

| High | 19.9 | 83.5 | 10.5 | 9.9 | 11.0 |

| Men | |||||

| African American | |||||

| Low | 10.9 | 82.0 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.8 |

| High | 11.9 | 83.4 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 9.1 |

| White non-Hispanic | |||||

| Low | 11.1 | 82.0 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 7.1 |

| High | 12.0 | 83.5 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 9.4 |

Abbreviations: LB, lower bound; UB, upper bound.

aResults from dynamic microsimulation based on probabilities from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1992 to 2009; lower bound of the 95% confidence interval from 1000 bootstrap samples for each population group; bootstrap sampling accounted for parameter variation and Monte Carlo variation; data represent non-Hispanic whites and African Americans; high education = college graduate; low education = grades 0 through 7; n = 2165; analytic sample = 15 078 transitions.

bConfidence intervals (not shown) do not differ from the point estimates at the level of precision shown.

Table 3 presents several measures of ADL disability for those with and without cognitive impairment. The left panel shows the average age of first ADL disability and the CI for that estimate. Among women who developed cognitive impairment, those with low education were younger at first ADL disability than those with high education—for example, 62.2 years versus 68.3 years among white participants (CIs 61.1-63.3, 66.8-69.8, respectively). There were analogous results for men.

Table 3.

Average Age of First ADL Disability and Measures of Permanent ADL Disability (Ending With Death).a

| Education | Age First Disabled | Permanent Disability | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %b | Mean Onset Age | Mean Years Disabled | ||||||||

| Age | LB | UB | Age | LB | UB | Years | LB | UB | ||

| With cognitive impairment | ||||||||||

| Women | ||||||||||

| African American | ||||||||||

| Low | 60.4 | 60.3 | 60.4 | 86.6 | 85.7 | 85.6 | 85.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.0 |

| High | 65.7 | 65.6 | 65.9 | 83.6 | 88.7 | 88.6 | 88.9 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.9 |

| White non-Hispanic | ||||||||||

| Low | 62.2 | 61.1 | 63.3 | 81.1 | 86.6 | 85.9 | 87.2 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 4.9 |

| High | 68.3 | 66.8 | 69.8 | 76.6 | 89.9 | 89.1 | 90.6 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 4.4 |

| Men | ||||||||||

| African American | ||||||||||

| Low | 61.2 | 61.1 | 61.3 | 81.9 | 85.1 | 84.9 | 85.2 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.7 |

| High | 67.0 | 66.8 | 67.2 | 77.6 | 88.8 | 88.6 | 88.9 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| White non-Hispanic | ||||||||||

| Low | 61.8 | 62.9 | 63.3 | 75.9 | 86.1 | 85.8 | 86.3 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 3.4 |

| High | 69.4 | 69.1 | 69.7 | 68.9 | 89.8 | 89.5 | 90.1 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| Without cognitive impairment | ||||||||||

| Women | ||||||||||

| African American | ||||||||||

| Low | 59.9 | 59.8 | 59.9 | 71.2 | 74.5 | 74.5 | 74.6 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| High | 64.3 | 64.3 | 64.4 | 69.9 | 80.9 | 80.8 | 81.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| White non-Hispanic | ||||||||||

| Low | 61.2 | 60.4 | 62.0 | 62.8 | 75.6 | 74.9 | 76.3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| High | 66.3 | 65.1 | 67.4 | 67.8 | 82.5 | 81.5 | 83.4 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| Men | ||||||||||

| African American | ||||||||||

| Low | 60.3 | 60.3 | 60.4 | 66.4 | 73.1 | 73.0 | 73.2 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| High | 64.9 | 64.9 | 65.0 | 65.0 | 79.7 | 79.6 | 79.8 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| White non-Hispanic | ||||||||||

| Low | 61.7 | 61.6 | 61.7 | 57.4 | 74.2 | 73.9 | 74.3 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| High | 66.6 | 66.5 | 66.8 | 54.5 | 81.1 | 80.7 | 81.5 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; LB, lower bound; UB, upper bound.

aResults from dynamic microsimulation based on probabilities from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1992 to 2009; lower bound of the 95% confidence intervals from 1000 bootstrap samples for each population group; bootstrap sampling accounted for parameter variation and Monte Carlo variation; data represent non-Hispanic whites and African Americans; high education = college graduate; low education = grades 0 through 7; n = 2165; analytic sample = 15 078 transitions. With cognitive impairment indicates individuals who become cognitively impaired at any age.

bPercentage with ADL disability in the month before death, or any number of months of uninterrupted ADL disability before death.

The remainder of Table 3 shows results for permanent ADL disability. The column labeled “%” shows the percentages of participants who had permanent disability, 1 or more months of ADL disability without recovery that end with death. In all groups, a higher percentage of those with cognitive impairment had permanent ADL disability than those without cognitive impairment. For example, among African American women with low education who did not develop cognitive impairment, 71.2% had permanent ADL disability, averaging 2.6 years (CI 2.5-2.6). The corresponding result for those with cognitive impairment was 86.6%, averaging 4.9 years (CI 4.8-5.0). As for education effects, in all groups except white women without cognitive impairment, those with higher education had less permanent ADL disability than those with less education. For example, among white men with cognitive impairment, 75.9% of those with low education had permanent ADL disability averaging 3.1 years; of those with high education, 68.9% had permanent disability averaging 2.6 years.

The average age of permanent ADL disability onset was substantially higher for those with cognitive impairment than for others. This is an expected result of greater longevity for those who develop cognitive impairment. In all instances, the mean age of onset was also higher for those with high education than for those with low education. For example, African American men with high education who became cognitively impaired developed permanent ADL disability at average age 88.8, compared with 85.1 for those with low education (CIs 88.6-88.9, 84.9-85.2, respectively). The mean duration of permanent disability was greater for those with cognitive impairment than for those without cognitive impairment. For example, among African American women with low education, those who became cognitively impaired had an average of 4.9 years of permanent disability (CI 4.8-5.0) compared with 2.6 years for others (CI 2.5-2.6). Among the simulated population that became cognitively impaired, those with high education had fewer years of permanent ADL disability than those with low education, despite the longer life expectancy and more years with cognitive impairment of those with high education.

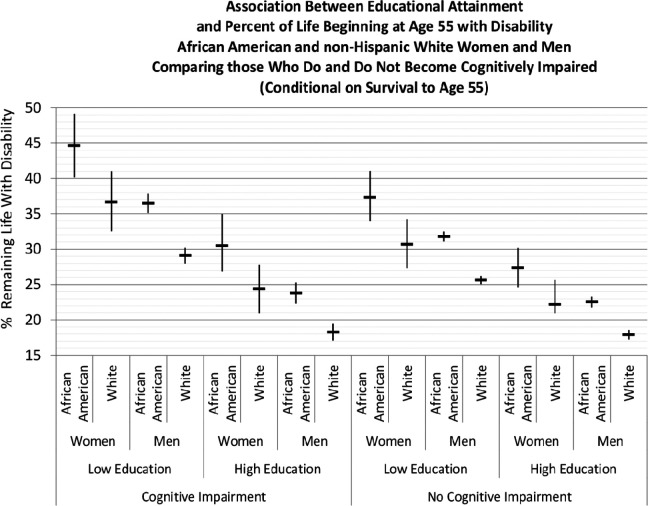

Figure 2 illustrates the latter point, showing the percentage of remaining life from age 55 with ADL disability. In all instances, those with less education lived a greater percentage of remaining life with disability. For example, among those who became cognitively impaired, African American women with low education lived 44.6% (CI 40.1-48.7) of remaining life with ADL disability compared with 30.5% (CI 26.9-35.0) of those with high education. The ratio of those rates was 1.46, indicating that the percentage for those with low education was 46% greater than for those with high education. Across all groups of those with cognitive impairment, the average analogous rate ratio was 1.5 (not shown in the figure). Thus, even among those who developed cognitive impairment, high education was associated with considerably less disability.

Figure 2.

Data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1992 to 2009. Horizontal bars indicate point estimates for the percentage of life beginning at age 55 with activities of daily living (ADL) disability; vertical lines identify the 95% confidence intervals estimated from 1000 bootstrap microsimulation samples for each population group; bootstrap sampling accounted for parameter uncertainty and Monte Carlo variation; high education = college graduate; low education = grades 0 through 7.

Discussion

This study extended active life expectancy research by modeling the effects of a health condition—cognitive impairment—that can develop throughout older life. It also extended research in this area by examining several new measures of disability. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that among people with cognitive impairment, those with more education lived longer. They also lived a smaller percentage of life with an ADL disability than those with less education and had fewer years with disability despite living more years with cognitive impairment. These results suggest that education may substantially limit ADL disability associated with cognitive impairment. The results may be attributable to less morbidity generally for those with more education or to a protective effect of education on cognitive functioning. The results for education and ADL disability are consistent with previous studies. However, most previous studies did not model ADL disability risks for those with cognitive impairment. 8,9,13,40 –43,45

We found that among older persons who developed cognitive impairment, the age of first disability was younger for those with low education than for those with high education. Among people who developed cognitive impairment, those with high education had permanent ADL disability onset at substantially older ages than those with low education. Also, permanent disability generally did not last as long for those with high education despite their older ages; thus, those with more education benefitted from a compression of morbidity. 10,35,39

Several considerations are relevant when interpreting our findings. Questions about disability vary among national surveys. For example, the Health and Retirement Study asks participants if they have “any difficulty” doing each ADL “because of a physical, mental, emotional, or memory problem,” and instructs them to “exclude any difficulties you expect to last less than 3 months.” 69 The PSID question did not require any minimum duration for the disability although it did ask only about functional limitations due to “a health or physical problem.” Participants responding to the PSID may therefore have been more likely than participants in the Health and Retirement Study to report temporary disabilities, such as those that may accompany a brief period of illness, injury, or surgery. As for education, although for some people poor health may influence educational attainment, most research suggests that education typically promotes health rather than being a function of previous health status. 9,16,19,24

Questions about cognitive health also vary among national surveys. The PSID asked whether a doctor had ever told the participant that she or he had a permanent loss of memory or mental ability. Related surveys ask: “have you had memory loss or loss of other cognitive functions?” (National Health Interview Survey) 53 ; “have you experienced confusion or memory loss that is happening more often or is getting worse” (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) 54 ; and, “has a health care professional ever said that you have Alzheimer’s disease or some other form of dementia?” (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System). 52 The Health and Retirement Study uses a more detailed cognitive battery that may identify cognitive impairment with greater validity. 69 This variation in the questions used to identify cognitive impairment is likely to result in differences in estimated disease rates, although estimates of health and disease from the PSID align well with those of other national surveys. 48,49 Responses to questions such as the PSID’s tend to be highly correlated with both disease and physician records. 70 However, self-reports of a doctor's diagnosis are related to symptom severity and may underrepresent cognitive problems. 70 People with more education have better access to health insurance and health care. 16,19,23,24 They may have cognitive impairment diagnosed at earlier stages than people with less access. Self-reports are subject to error even when interviewers ask only about physician diagnoses.

We adjusted our results for major sources of variation including repeated measures, parameter uncertainty, and Monte Carlo variation. Previous related research has not typically accounted for all of these sources of variation—particularly repeated measures, which in this study had the greatest effect on variance. Like most research using these methods, our analysis did not account for the PSID sampling design. We examined the design effect, the ratio of the variance in an analysis that accounts for the design to one that does not. 71 It was 1.30 for the measures of cognitive function and disability, 1.15 for gender, 1.07 for ethnicity, and 1.60 for education. Adjusting for these effects would widen the CIs used in the microsimulations and increase the CIs of the final results. However, accounting for design effects principally affects standard errors and CIs, rather than point estimates. Thus, our estimates for average active life expectancy and average years with ADL disability would not change meaningfully if adjusted for design effects. 66 Also it is likely that the variance adjustment using the random effect model accounted for a substantial proportion of the variation associated with the survey design, because the random effect adjusts for all variation at the individual level that is not represented by measured variables in the model.

Conditions such as diabetes or hypertension increase the risk of cognitive impairment. They also increase the risk of disability. We do not know if people who had such conditions were disabled principally by cognitive impairment or more directly by those conditions. We addressed this consideration, in part, by stratifying by gender, ethnicity, and education and using transition probabilities specific to age, all of which are associated with such risk factors. Of greatest interest in the present study, however, is not whether it is cognitive impairment or some other risk factor that specifically causes ADL disability among those with cognitive impairment. What is important in our results is that among people with cognitive impairment the risks of ADL disability were considerably lower for those with more education. This lower risk may be due to more brain reserve or some other protective effect of education for the brain. Or, it may be due to less diabetes or hypertension for those with more education, or better control of those conditions, or more physical activity or better diets, or fewer other risks for ADL disability. Regardless of the mechanism, our results provide evidence that having more education is associated with less ADL disability in older age even among individuals who become cognitively impaired. Cognitive impairment and disability are common at older ages. The loss of memory, the loss of independence, and the reliance on others that accompany advanced cognitive impairment are among the greatest fears of older adults. 72,73 Thus, we believe it is useful to know that people with more education often avoid the ADL disability that is associated with severe cognitive impairment.

Cognitive impairment often reduces quality of life by causing disability, particularly in advanced stages of dementia when ADL disability is common. Our findings suggest that education is associated with less ADL disability for those with cognitive impairment, despite the fact that people with more education are more likely to live to older ages when ADL disability is common. This result was also obtained in spite of the finding that among people who became cognitively impaired, those with high education lived more years with that impairment. Findings may provide support for investing in education and for the growing public health efforts to promote cognitive health by encouraging healthy behaviors that are more common among people with more education. 22,27 –32,74 –77

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Tornquist, MA, and 2 anonymous reviewers for useful comments about this research.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Portions of preliminary results of this study were presented as a peer reviewed poster at the American Public Health Association 141st Annual Meeting. Boston, MA, November 2-6, 2013, titled “More education may limit the impact of cognitive impairment on disability and life expectancy for older Americans.” The data used for this study are available from The Panel Study of Income Dynamics, http://simba.isr.umich.edu/data/data.aspx.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Heyn P, Abreu BC, Ottenbacher KJ. The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(10):1694–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Adult children helping older parents: variations in likelihood and hours by gender, race, and family role. Res Aging. 2001;23(4):429–456. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laurin D, Verreault R, Lindsay J, MacPherson K, Rockwood K. Physical activity and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly persons. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lautenschlager NT, Cox K, Kurz AF. Physical activity and mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10(5):352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Potter R, Ellard D, Rees K, Thorogood M. A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on physical functioning, quality of life and depression in older people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(10):1000–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2015–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2012: Key Indicators of Well-Being. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crimmins EM, Saito Y. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the United States, 1970-1999: gender, racial, and educational differences. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(11):1629–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freedman VA, Martin LG. The role of education in explaining and forecasting trends in functional limitations among older Americans. Demography. 1999;36(4):461–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laditka SB, Laditka JN. Active life expectancy: a central measure of population health. In: Uhlenberg P, ed. International Handbook of the Demography of Aging. Netherlands: Springer-Verlag; 2009:543–565. [Google Scholar]

- 11. EClipSE Collaborative Members. Education, the brain and cognitive impairment: neuroprotection or compensation? Brain. 2010;133(pt 8):2210–2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marioni RE, Valenzuela MJ, van den Hout A, Brayne C. MRC Cognitive function and ageing study. active cognitive lifestyle is associated with positive cognitive health transitions and compression of morbidity from age sixty-five. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e50940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matthews FE, Jagger C, Miller LL, Brayne C, MRC CFAS. Education differences in life expectancy with cognitive impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(1):125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(3):448–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005:294(22):2879–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feinstein JS. The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: a review of the literature. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1993;71(2):279–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glied S, Lleras-Muney A. Technological innovation and inequality in health. Demography. 2008;45(3):741–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Education, personal control, lifestyle and health: a human capital hypothesis. Res Aging. 1998;20(4):415–449. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Rouz A, Kawachi I, Levin B. Fundamental causes’ of social inequalities in mortality: a test of the theory. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(3):265–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pope AM, Tarlov A, eds. Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seemam T, Merkin SS, Crimmins E, Koretz B, Charette S, Karlamangla A. Education, income and ethnic differences in cumulative biological risk profiles in a national sample of US adults: NHANES III (1998-1994). Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(1):72–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):819–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jemal A, Ward E, Anderson RN, Taylor M, Thun MJ. Widening of socioeconomic inequalities in U.S. death rates, 1993–2001. PLoS One. 2008;3(5):e2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Refining the association between education and health: the effects of quantity, credential, and selectivity. Demography. 1999;36(4):445–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Seeman TE. Poverty and biological risk: the earlier “aging” of the poor. J Gerontol A Med Sci. 2009;64(2):286–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ross CE, Van Willigen M. Education and the subjective quality of life. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(3):275–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Albert M, Brown DR, Buchner D, et al. The healthy brain and our aging population: translating science to public health practice. foreword. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(2 suppl):S3–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Shah RC, Wilson RS, Bennett DA. Total daily physical activity and the risk of AD and cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1323–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Etgen T, Sander D, Huntgeburth U, Poppert H, Forstl H, Bickel H. Physical activity and incident cognitive impairment in elderly persons: the INVADE study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(2):186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu R, Sui X, Laditka JN, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of cognitive impairment mortality in men and women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(2):253–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scarmeas N, Luchsinger JA, Schupf N, et al. Physical activity, diet, and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2009;302(6):627–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vercambre M-N, Grodstein F, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Kang JH. Physical activity and cognition in women with vascular conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1244–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Laditka SB, ed. Health Expectations for Older Women: International Perspectives. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 2002:196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Robine JM, Jagger C, Mathers C, Crimmins EM, Suzman R, eds. Determining health expectancies. Chichester, Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2003:111–125. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crimmins EM, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Sci Soc Sci. 2010;66(1):75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Laditka SB, Hayward MD. The evolution of demographic methods to calculate health expectancies. In: Robine JM, Jagger C, Mathers CD, Crimmins EM, Suzman RM, eds. Determining Health Expectancies. Chichester, Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2003:221–234. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Hagedorn A, Saito Y, Brouard B. Change in disability-free life expectancy for Americans 70 years old and older. Demography. 2009;46(3):627–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hayward MD, Heron M. Racial inequity in active life among adult Americans. Demography. 1999;36(1):77–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Laditka SB, Laditka JN. Recent perspectives on active life expectancy for older women. J Women Aging. 2002;14 (1/2):163–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Molla MT, Madans JH, Wagener DK. Differentials in adult mortality and activity limitation by years of education in the United States at the end of the 1990s. Popul Dev Rev. 2004;30(4):625–646. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Saito Y. Differentials in active life expectancy in the older population of the United States. J Gerontol B Sci Soc Sci.1996;51(3):S111–S120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guralnik JM, Land KC, Blazer D, Fillenbaum GG, Branch LG. Educational status and active life expectancy among older blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(2):110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Effects of diabetes on healthy life expectancy: shorter lives with more disability for both women and men. In: Yi Z, Crimmins E, Carrière Y, Robine JM, eds. Longer Life and Healthy Aging. Netherlands: Springer; 2006:71–90. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Laditka SB, Laditka JN. Effects of improved morbidity rates on active life expectancy and eligibility for long-term care services. J Appl Gerontol. 2001;20(1):39–56. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Laditka SB, Wolf DA. New methods for analyzing active life expectancy. J Aging Health. 1998;10(2):214–241. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lièvre A, Alley D, Crimmins EM. Educational differentials in life expectancy with cognitive impairment among the elderly in the United States. J Aging Health. 2008;20(4):456–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alzheimer’s Association. Seven stages of Alzheimer’s; 2013. http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_stages_of_alzheimers.asp. Accessed May 18, 2013.

- 48. Hill M. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics: A User’s Guide. Newbury CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Burkhauser RV, Weathers R, Schroeder M. A guide to disability statistics from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics . Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Disability Demographics and Statistics. Disability Statistics User Guide Series Technical Series Paper #06-02. Ithaca, NY: The Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Disability Demographics and Statistics at Cornell University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Olatosi B, Elder KT. The health tradeoff of rural residence for impaired older adults: longer life, more impairment. J Rural Health. 2007;23(2):124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Laditka JN, Wolf DA. Improving knowledge about disability transitions by adding retrospective information to panel surveys. Popul Health Metr. 2006; 4:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillence System. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillence System; 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Accessed May 18, 2013.

- 53. National Health Interview Survey. National Health Interview Survey; 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/new_nhis.htm. Accessed January 26, 2011.

- 54. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. Accessed May 18, 2013.

- 55. Xie J, Crayne C, Matthews FE; Medical Research Council Function and Aging Study collaborators. Survival times in people with dementia: analysis from population based cohort study with 14 year follow-up. BMJ. 2008;336(7638):258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1737–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures; 2013. http://www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2013.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58. McDougall G J, Vaughan P, Acee T, Becker H. Memory performance and mild cognitive impairment in Black and White community elders. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(2):381–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1-2):125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Land KC, Guralnik JM, Blazer DG. Estimating increment-decrement life tables with multiple covariates from panel data: the case of active life expectancy. Demography. 1994;31(2):297–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, Colen CG, Steffick D. Inequity in life expectancy, functional status, and active life expectancy across selected black and white populations in the United States. Demography. 2001;38(2):227–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Laditka SB. Modeling lifetime nursing home use under assumptions of better health. J Gerontol B Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(4):S177–S187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lièvre A, Brouard N, Heathcote C. The estimation of health expectancies from cross-longitudinal surveys. Math Popul Stud. 2003;10(4):211–248. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Reynolds SL, Saito Y, Crimmins EM. The impact of obesity on active life expectancy in older American men and women. Gerontologist. 2005;45(4):438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yong V, Saito Y. Are there education differentials in disability and mortality transitions and active life expectancy among Japanese older adults? Findings from a 10-year prospective cohort study. J Gerontol B Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67(3):343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cai L, Hayward MD, Saito Y, Lubitz J, Hagedorn A, Crimmins E. Estimation of multi-state life table functions and their variability from complex survey data using the SPACE program. Demogr Res. 2010;22(6):129–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wolf D. A Random-Effects Logit Model for Panel Data. IIASA Working Paper WP_87 104. Laxenburg, Austria: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wolf DA, Laditka SB, Laditka JN. Patterns of active life among older women: differences within and between groups. J Women Aging. 2002;14 (1/2):9–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Health and Retirement Study. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/. Accessed May 18, 2013.

- 70. Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Seeman T. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status and health. In: Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, eds. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Later Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2004:310–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lohr SL. Sampling Design and Analysis. 2nd ed. Boston: Brooks/Cole; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Liu R, et al. Older adults’ concerns about cognitive health: commonalities and differences among six United States ethnic groups. Ageing Soc. 2011;31(7):1202–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Liu R, et al. How do older people describe others with cognitive impairment? A multiethnic study in the United States. Ageing Soc. 2013;33(3):369–392. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, & Alzheimer’s Association. The Healthy Brain Initiative: A National Public Health Road Map to Maintaining Cognitive Health. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Laditka SB, Corwin SJ, Laditka JN, et al. Attitudes about aging well among a diverse group of older Americans: implications for promoting cognitive health. Gerontologist. 2009;49(suppl 1):S30–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC Healthy Brain Initiative: Progress 2006-2011. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Lowe KB. Promoting cognitive health: a website review of health systems, public health departments, and senior centers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(8):600–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]