Abstract

Spatial navigation is one of the cognitive functions known to decline in both normal and pathological aging. In the present study, we aimed to assess the neural correlates of the decline of topographical memory in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI). Patients with aMCI and age-matched controls were engaged in an intensive learning paradigm, lasting for 5 days, during which they had to encode 1 path from an egocentric perspective and 1 path from an allocentric perspective. After the learning period, they were asked to retrieve each of these paths using an allocentric or egocentric frame of reference while undergoing a functional magnetic resonance imaging scan. We found that patients with aMCI showed a specific deficit in storing new topographical memories from an allocentric perspective and retrieving stored information to perform the egocentric task. Imaging data suggest that this general decline is correlated with hypoactivation of the brain areas generally involved in spatial navigation.

Keywords: navigation, topographical memory, MCI, fMRI

Introduction

Spatial navigation—which is the ability to retain the spatial layout of an environment, find a shortcut between 2 locations, or create an interconnected network among different paths 1 —is one of the cognitive functions subjected to decline in both normal 2 -4 and pathological aging. 5 -7

Indeed, spatial navigation is a complex ability, which taps on different processes and requires different brain structures. 1,8 Three central processes with their relative neurofunctional substrate have been identified as central to navigation: (1) the acquisition and storage of egocentric spatial representation (i.e., representations that have as frame of reference one’s own body), related to a network of parieto-occipital areas; (2) the acquisition and storage of allocentric spatial representation (i.e., representations that have an external, world-centered frame of reference), related to a network of areas mainly situated in the medial temporal lobe; and (3) a process of translation between these two types of representations, related mainly to the retrosplenial complex. 8 Noteworthy, so-defined egocentric and allocentric representations are known as route and survey knowledge in the field of cognitive psychology. 9,10 More recent evidence seems to suggest that allocentric spatial representation emerges from the interaction among different brain regions rather than the computation of a single brain region, that is the hippocampus. 11

Topographical disorientation may occur as the consequence of acquired focal brain damages, 12,13 as a result of congenital brain malformations 14 or as a developmental selective deficit in people who have no cerebral damage or perinatal problems and who never learn to navigate in the spatial environment. 15 -21 Commonly, healthy older adults show a general decline in navigation abilities, which seems to include both task requiring encoding or recalling egocentric and allocentric representations. 2 -4,6,7 Nevertheless, older adults were found to perform similarly to young individuals on memory for the layout of long familiar landmarks, 22 supporting the hypothesis that repeated experience yields a more schematic, semantic-like representation. 23,24

Spatial navigation deficits may represent the first sign of Alzheimer’s disease (AD 25 ) and are often detectable before the onset of the full dementia symptoms in mild cognitive impairment (MCI 5,26 ). In particular, patients with amnestic MCI (aMCI), a particular case of MCI with selective memory deficit, have been found to be impaired in both egocentric and allocentric strategies. 27 Patients with aMCI have been found to perform worse than healthy age-matched controls in learning a new route, replacing landmarks in the city and drawing the city map, whereas performances of patients with non-aMCI did not differ from those of control participants. 28 Furthermore, with both single and multiple domains, patients with aMCI showed a deficit in processing categorical spatial information during a virtual reorientation task. 29

Several studies have tried to understand the neural mechanisms of age-related changes in spatial navigation (see Wolbers et al 30 ), especially linking the deficits in encoding and storing the allocentric representation 31 to the early damage of the medial temporal lobe structures (reviewed in Vlček and Laczó 32 ), as well as the egocentric deficit with the involvement of structures such as the posterior parietal lobe and the precuneus. Accordingly, Weniger and colleagues 27 found that the volumes of the right precuneus significantly predicted the performance in an egocentric task (ET, i.e., virtual maze) in both MCI and healthy older adult participants. Moreover, apart from the encoding and retrieval of allocentric and egocentric representations, the deficit in the translation between these two types of representations could be related to early atrophy of the retrosplenial cortex (RSC). 32 Interestingly, impairment in translating allocentric hippocampal representation in the egocentric parietal ones for the purpose of effective spatial orientation and navigation has been linked to the damage of the hippocampus and RSC of patients with AD, 33 -35 and it has been proposed as a deficit in “mental frame syncing,” that is, a deficit synchronizing the viewpoint-independent representation with the viewpoint-dependent representation. 34,35

In the light of the literature, it seems that healthy older adults and patients with MCI share, even if with a different degree of severity, a global deficit in navigational abilities that could be related to similar abnormal changes situated on a continuum. However, an extensive investigation focusing on different kinds of spatial representations (i.e., allocentric and egocentric) and their interaction (i.e., translation) comparing healthy older adults and patients with MCI is still missing.

In the present study, we aimed to assess the neural correlates of the decline of topographical memory in patients with aMCI, directly testing the possibility of a selective deficit in specific spatial representation. Actually, we investigated the effect of the frame of reference used (1) to form new topographical memories and (2) to access topographical information from memory from both a behavioral and neural point of view, in a sample of patients with aMCI and healthy controls (HCs). To pursue our aim, we used an intensive learning paradigm, 36 which lasted 5 days, during which participants had to encode 2 paths in the same real city: one in an egocentric frame (egocentric learning [EL]) and the other in an allocentric frame (allocentric learning [AL]). Then, we asked the participants to retrieve each of these paths using a task tapping on an allocentric representation (allocentric task [AT]) or an egocentric representation (ET) while undergoing a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scan. The tasks were performed twice, on the first and the fifth days of training, to assess the effect of familiarization with the novel environment and its interaction with the frame of reference. 36 We expected to find a general impairment in navigational abilities in patients with aMCI, especially in task requiring the allocentric frame of reference 32 and that such an impairment would be associated with hypoactivation in the brain areas related to spatial navigation and topographical memory, such as hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus (PHG), and RSC. Moreover, we expected the deficit to be more pronounced when patients with MCI had to translate the spatial representation from a frame of reference to the other (e.g., when they had to solve the ET within the path learnt in the allocentric frame of reference).

Materials and methods

Participants

Eight patients with a diagnosis of aMCI (1 female) and 8 age-matched control participants (HC; 1 female) took part in this study (patients with aMCI mean age = 75.00 ± 6.41; HC mean age = 69.75 ± 5.75; t = −1.14, P = .14). The 2 groups were also matched for education (aMCIs mean education = 11.38 ± 5.93; HC mean education = 11.75 ± 2.31; t = 1.17, P = .87).

Amnestic MCIs were recruited at CEMI, the Aging Medicine Centre of “Policlinico Agostino Gemelli” in Rome, and diagnoses were made by an expert neurologist (M.C.S.). According to accepted criteria for the diagnosis of aMCI, 37 all of them had a clinical history of isolated memory deficit, confirmed by their relatives, with full preservation of the functional abilities and autonomy in daily life. Consistently, the neuropsychological examination with standardized measures (see Table 1) confirmed a decay in the declarative memory tests (as compared with normative data on Italian population) in the absence of major deficits in other cognitive domains (see Table S1 in supplementary materials for more details); the Clinical Dementia Rating score was 0.5 in all participants (Table 1). No participant had a positive history for psychiatric diseases, alcohol or drug abuse, or acute cerebrovascular disorders.

Table 1.

Personal and Clinical Data.a

| Patient | Sex | Age | Education | MMSE | CDR | Abstract Reasoning (RM) | Short-Term Memory (Verbal; RW) | Long-Term Memory (Verbal; RW) | Long-Term Memory Recognition (RW) | Visual Memory (ROF) | CA (ROF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 77 | 13 | 27 | 0.5 | 24 | 29 | 3 | 15/15; FR = 16/30 | 9.5 | 22 |

| 2 | F | 72 | 13 | 23 | 0.5 | 26 | 19 | 0 | 12/15; FR = 4/30 | 0 | 21.5 |

| 3 | M | 64 | 5 | 23 | 0.5 | 24 | 22 | 0 | 15/15; FR = 14/30 | 2 | 29 |

| 4 | M | 76 | 8 | 24 | 0.5 | 22 | 28 | 1 | 7/15; FR = 7/30 | 1.5 | 27 |

| 5 | M | 82 | 21 | 24 | 0.5 | 27 | 29 | 2 | 14/15; FR = 17/30 | 4.5 | 34 |

| 6 | M | 69 | 5 | 21 | 0.5 | 26 | 16 | 2 | 8/15; FR = 5/30 | 0 | 21.5 |

| 7 | M | 83 | 18 | 25 | 0.5 | 30 | 25 | 4 | 14/15; FR = 11/30 | 10 | 34 |

| 8 | M | 77 | 11 | 27 | 0.5 | 28 | 23 | 1 | 2/15; FR = 0/30 | 8 | 32.5 |

Abbreviations: CA, Constructional Apraxia (Spinnler & Tognoni, 1987); CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; RM, Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Basso et al, 1987); ROF, Rey and Osterrieth’s figure (Rey, 1941; Osterrieth, 1944); RW, Rey’s Words (Rey, 1958).

aPathological scores are in bold.

Healthy controls had normal Mini-Mental State Examination scores 38 and no history of neurological or psychiatric diseases. None of them have reported memory difficulties or deficits in other cognitive dimensions. All participants gave their written informed consent. This study was approved by the local ethical committee of Santa Lucia Foundation and that of “Policlinico Agostino Gemelli” in Rome, in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants were unfamiliar with the city we used to create the stimuli; so that the 2 paths administered during the intensive learning were completely unknown to them at the beginning of the training.

From the initial sample, 1 of 8 aMCIs and 1 of 8 HCs refused to perform the entire fMRI acquisition; thus, their data were only included in the behavioral data analysis and structural brain imaging analysis. Also, fMRI acquisition from 1 HC was discharged due to artifacts during acquisition.

Stimuli and Procedure

Experimental procedures and materials have been validated in a previous study. 36 For the intensive learning, we used a set of stimuli developed in the city of Latina, which is located about 90 km from Rome. This city was built during the 1930s in a rationalist architectural style. Thus, it has a simple grid-like plan. The set of stimuli included both video clips and maps of 2 paths through the city (path A and path B). Each path was about 9-km-long, with 23 crossroads. In each path, the number of turns was balanced across 3 possible directions (i.e., straight, left, and right).

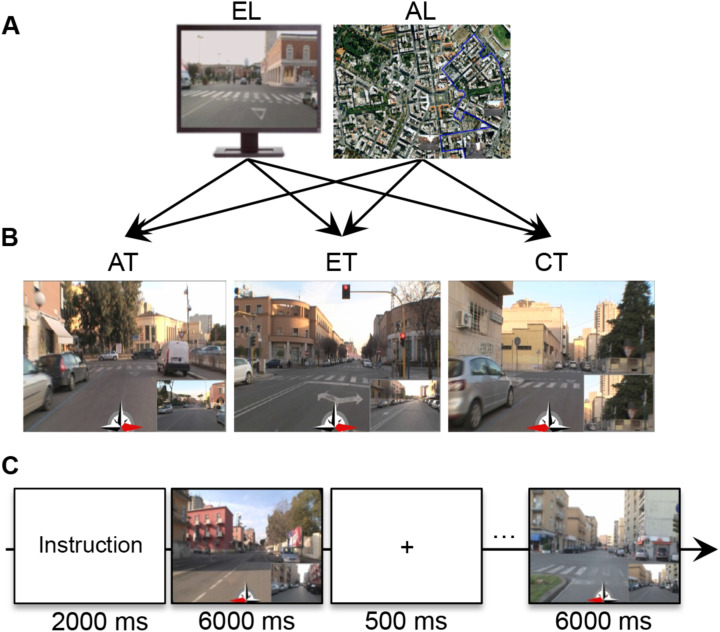

A professional cameraman recorded video clips of the 2 paths from a first-person perspective. The maps of these paths were created using Google Maps 2011 (satellite vision). In each map, a blue line indicated the path. A set of 23 postcards of each path showed the crossroads from a first-person perspective. The video clips were used to encourage participants to develop an egocentric representation (EL) of the city, and the maps were used to encourage them to develop an allocentric representation (AL; Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Method. A, Intensive spatial training materials: video clips from egocentric learning are on the left, and maps from allocentric learning are on the right. B, Experimental task materials used during the fMRI scans in the first and second sessions: from the left, allocentric task, egocentric task, and control task. C, Experimental timelines during fMRI. AL indicates allocentric learning; AT, allocentric task; CT, control task; EL, egocentric learning; ET, egocentric task; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging.

For the retrieval tasks, 23 screenshots were taken from the video clips of each path. The screenshots depicted the 23 crossroads along each path. Using these screenshots, we created 2 sets of stimuli—that is, 42 stimuli for path A and 42 stimuli for path B—to test the spatial representations acquired during learning. Each stimulus had a red arrow at the bottom center that pointed in 1 of 3 possible directions (i.e., left, straight, or right) and a little panel at the bottom right of the picture that indicated (1) either the next step on the path in the ET, (2) or the starting or goal point in the AT, and (3) a detail of the current visual scene in the control task (CT; Figure 1B).

Procedure

The experiment took place on 5 consecutive days (Figure 1D). On the first day (prelearning), participants were shown the 2 paths in both the egocentric and the allocentric perspective (i.e., path A-EL, path A-AL, path B-EL, and path B-AL) in random order. After the presentation, participants were submitted to an fMRI scan during which they performed the retrieval task (described below).

After the first session, the participants were engaged in intensive EL and AL, which lasted 4 consecutive days (Figure 1D), during which half of them learned path A in an egocentric perspective and path B in an allocentric perspective and half learned path A in an allocentric perspective and path B in an egocentric perspective (Figure 1A).

Egocentric representation, based on the presentation of the video recorded along the path, forced the participants to encode the path from an egocentric perspective (i.e., encoding the direction at each crossroad based on its own orientation in space). Each video clip lasted 7 minutes.

The EL was based on trial-and-error learning. The presentation of the video clips stopped at each crossroad. Participants were asked to indicate the direction in which the path proceeded by pressing the arrow keys on a keyboard. The video clip presentation started again only after they had indicated the correct direction. The time spent at each crossroad between the video clip stop and the correct response was recorded and was used as a measure of learning across prelearning and the 4 days of learning.

On the other hand, AL forced the participants to form allocentric representation of the environment (i.e., encoding the map-like representation of the environment). An allocentric representation was elicited by presenting a map of the city with the starting and ending points of the path represented by means of postcards; a blue line connecting the starting-postcard and the goal-postcard was drawn to represent the path. Participants were asked to learn the map by observing the experimenter who consecutively placed the postcards representing each crossroad along the path on the map. After the experimenter had positioned all of the cards, the cards were shuffled and the participants were asked to place the card in the correct location. Verbal feedback (correct/incorrect) was given for each postcard. If they made an error, participants were allowed to continue to place the postcards until they found the correct location. Both the time needed to perform the task and accuracy were recorded and were used as measures of learning during prelearning and the 4 days of intensive learning.

The order of the learning presentation (AL and EL) was balanced across participants.

On the first (prelearning) and the last days of learning, participants underwent an fMRI scan during which they were engaged in 2 retrieval tasks and 1 control forced-choice task (Figure 1B), presented in 3 separate runs. In the retrieval tasks, the acquired representations of both paths had to be retrieved in both an allocentric and an egocentric frame. In the AT, participants had to retrieve an allocentric representation of the 2 learned paths. In each trial of the AT, participants watched a stimulus that represented (1) a screenshot depicting a crossroad of one of the 2 paths, (2) a smaller panel depicting the starting or the goal point of the same path, and (3) a central red arrow (see Figure 1B); participants were asked to judge whether the direction of the red arrow corresponded to the location of the crossroad with respect to the starting/goal point. In half of the trials, the red arrow pointed to the correct direction, and in half of the trials, it pointed to a wrong direction.

In the ET, participants had to retrieve an egocentric first-person perspective representation of the paths. In each ET trial, they watched (1) screenshots depicting a crossroad of one of the 2 paths, (2) a smaller panel depicting the following crossroad on the same path, and (3) a red arrow, and they were asked to indicate whether the red arrow pointed or not to the direction (i.e., left, straight, right) they would have to follow to reach the next crossroad along the path (see Figure 1B). As in the ET task, in half of the trials, the red arrow pointed in the correct direction, and in half, it pointed in a wrong direction.

Unlike the AT and ET, in the CT, participants did not have to retrieve any spatial information about familiarized paths; they just had to visually explore the scenes. In each CT trial, participants watched (1) screenshots of a crossroad of one of the 2 paths, (2) a detail of the same crossroad in the bottom panel, and (3) a red arrow; they were asked to indicate whether the central red arrow pointed toward the area of the picture where the detail depicted in the little box was located (see Figure 1B). Also, in the CT, the red arrow pointed toward the correct direction in half of the trials and toward a wrong direction in the other half.

Tasks were administered in balanced order across participants in 3 different fMRI runs. In each fMRI run, participants were presented 84 trials, divided into 12 blocks each, including 7 trials. Trials from the different paths (A or B) were presented in different blocks. The block order was balanced across participants, and trial presentation was randomized within each block. Each block began with written instructions about the path (path A or B), which remained on the screen for 2 seconds. Each trial remained on the screen for 6 seconds and was followed by a fixation point, which lasted 500 milliseconds (Figure 1C). The interval between blocks lasted for 20 seconds, during which a fixation point was presented. Subjects pushed the right or left button of a hand pad if they thought the trial was true or false, on the basis of the information acquired during the learning session before the scan. For each task, we calculated individuals’ accuracy considering the type of learning (EL or AL). For each task, accuracy was defined as the sum of both the correctly identified and the correctly rejected trials. The experiment was implemented in Matlab, using Cogent 2000 (Wellcome Laboratory of Neurobiology, UCL, London, http://www.vislab.ucl.ac.uk/cogent.php).

Image Acquisition

A Siemens Allegra scanner (Siemens Medical System, Erlangen, Germany), operating at 3T and equipped for echo planar imaging, was used to acquire functional magnetic resonance images. Head movements were minimized by mild restraint and cushioning. We acquired 38 slices of fMRI images using blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) imaging (in-plane resolution 3 × 3 × 3 mm, slice thickness 2.5 mm, interslice distance 1.25 mm, time repetition 2.47 seconds, time echo 30 milliseconds), covering the entire cortex. We also acquired a 3-dimensional, high-resolution, T1-weighted structural image for each participant (Siemens MDEFT, 176 slices, in-plane resolution = 1 × 1 mm, slice thickness = 1 mm, TR = 7.92 seconds, TE = 2.4 seconds).

Image Analysis

Image analyses were performed using SPM8 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/SPM) running in MATLAB 7.1 (The Math-Works Inc, Natick, Massachusetts). For each participant, 332 fMRI volumes were acquired in each of the 3 runs. The first 4 volumes of each run were discarded to allow for T1 equilibration. All images were corrected for head movements (realignment) using the first slice as reference. Corrected images were normalized to the standard Montreal Neurological Institute echo planar imaging template using the mean realigned image as source and then spatially smoothed using an 8-mm full-width half-maximum (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian kernel. Functional images were analyzed for each participant separately on a voxel-by-voxel basis according to the general linear model. Neural activation during the blocks was modeled as a boxcar function spanning the whole duration of the blocks and convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function, which was chosen to represent the relationship between neuronal activation and blood oxygenation. 39 Separate regressors were included for each combination of session (first or fifth day of training), task (AT, ET, CT), and learning (EL or AL). Interblock intervals were also modeled in relation to the nature of the previous block (EL-rest or AL-rest) and treated as baseline. Group analyses were performed on estimated images that resulted from the individual models of each condition compared with its baseline, treating participant as a random factor.

Region of Interest Analysis

We set out to compare BOLD activation of HCs and MCIs in regions classically involved in topographical memory (i.e., hippocampus, PHG, and RSC) during different experimental conditions (relative to session, tasks, and learning). We initially performed a voxel-wise analysis across the whole brain by means of a full factorial design, including group (HC and aMCI), session (first and fifth day of training), and tasks (ET, AT, and CT) as factors. We then performed a full factorial design over the second session parameters, including group (HC and aMCI), tasks (ET, AT, and CT), and learning (EL and AL) as factors. We computed F-omnibus contrasts for all conditions, and the resulting statistical parametrical maps were thresholded at P FWE < .05. We extracted percentage of BOLD signal changes of left and right hippocampus (HC-LH and RH), PHG (PHG-LH and RH), and RSC (RSC-LH and RH) using anatomical masks of such regions (anatomical regions of interest [ROIs] were obtained from the Anatomical Automatic Labeling (AAL) ROI library 40 ). For each subject and region, we computed a regional estimate of the amplitude of the hemodynamic response in each experimental condition by entering a spatial average (across all voxels in the region) of the preprocessed time series into the individual general linear models. Thus, the regional hemodynamic response was analyzed with 2 mixed factorial design analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with the same factorial structures of the full factorial designs mentioned above. The first one, which had a 2 × 2 × 3 factorial design (group [HC and aMCI] by session [first vs fifth day] by task [AT vs ET vs CT]), was aimed at exploring the effect of the group in the 2 experimental sessions of the intensive spatial training and tasks. The second one, which had a 2 × 3 × 2 factorial design (group [HC and aMCI] by task [AT vs ET vs CT] by learning [EL vs AL]), focused on the last session and was aimed at exploring the effect of the group on different learning strategies and tasks. In both cases, age was entered as covariate. Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons correction was applied on post hoc pairwise comparisons.

Voxel-Based Morphometry Analysis

We performed a voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis on participants’ T1-weighted structural image, using VBM8 Toolbox, implemented in SPM8. The T1 anatomical images were manually checked for scanner artifacts and gross anatomical abnormalities. The images were then normalized using high-dimensional Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration Through Exponentiated Lie Algebra (DARTEL) normalization, segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and smoothed (FWHM 8 mm). A 2-sample t test second-level statistical test was used to compare the smoothed GM images of individuals with aMCI and HCs.

Behavioral Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20. We first performed two 2 × 5 ANOVAs (group (HC and aMCI) by days of training [days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5]) on learning performance on EL and AL, with the first one measured as time spent at each crossroad (or choice point) and the second one measured as the number of correctly positioned postcards. Then, we performed 2 mixed factorial ANOVAs on participants’ accuracy in the behavioral tasks during the fMRI scans. The first 2 × 2 × 3 ANOVA (group [HC and aMCI] by session [first and fifth day] by task [AT, ET and CT]) was aimed at exploring the effect of the group on performances in the 2 experimental sessions of the intensive spatial training and tasks. The second 2 × 3 × 2 ANOVA (group [HC and aMCI] by task [AT, ET and CT] by learning [EL and AL]) was led on accuracy at the fifth day of training to directly assess the effect of the group on different learning strategies and tasks after the intensive spatial training. In both cases, age was entered as covariate and post hoc pairwise comparisons were led using Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

Behavioral Results

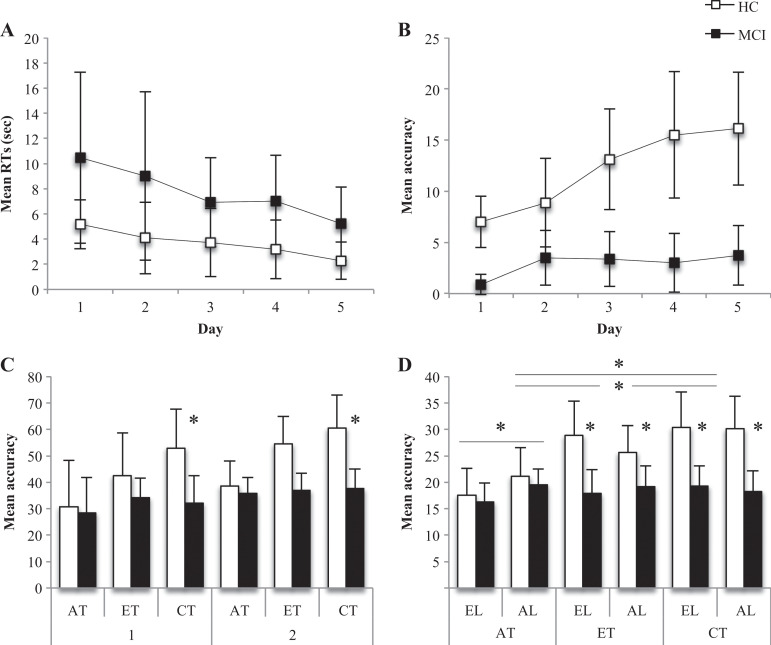

The 2 × 5 ANOVA on EL across 5 days of intensive learning failed in finding significant effects, even if the 2 groups showed slightly different patterns of learning across the 5 days of learning (see Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Behavioral results. A, Egocentric learning performances across the 5 days of intensive spatial training (mean and SD of response times). B, Allocentric learning performances across the 5 days of intensive spatial training (mean and SD of accuracy). C, Performance accuracy on the 3 experimental tasks performed in the first (1) and second sessions (2) during fMRI scans (mean and SD). D, Performance accuracy on the 3 experimental tasks performed in the 2 learning conditions in the second session during fMRI scans (mean and SD). AL, allocentric learning; AT, allocentric task; CT, control task; EL, egocentric learning; ET, egocentric task; HC, healthy controls; MCI, patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment; SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of variance on AL showed a main effect of group (F 1,13 = 26.878, P = .000) and a group-by-day interaction (F 4,52 = 4.262, P = .005). On average, HCs performed better (mean = 12.125, standard deviation [SD] = 4.689) than aMCIs (mean = 2.900, SD = 2.425) in AL, that is, in positioning the postcards correctly depicting each crossroad (Figure 2B). Concerning the group-by-task interaction, post hoc analysis showed that the 2 groups differed every day in performing AL, and the difference increased with the intensive spatial learning (first day of learning: P = .000; second day of learning: P = .032; third day of learning: P = .001; fourth day of learning: P = .001; fifth day of learning: P = .000; see Figure 2B).

The 2 × 2 × 3 ANOVA on participants’ accuracy showed a group-by-task interaction (F 2,22 = 6.109, P = .008). Post hoc comparisons showed that the 2 groups (HC and aMCI) significantly differed in performing CT, with HC performing better than aMCI (P = .010, Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons, Figure 2C). No other significant effect was found.

The 2 × 3 × 2 ANOVA on participants’ accuracy at the second fMRI session showed a main effect of group (F 1,12 = 6.460, P = .026) and task (F 2,24 = 5.285, P = .013) as well as group-by-task (F 2,24 = 13.705, P = .000) and task-by-learning (F 2,24 = 3.737, P = .039) interactions. Healthy controls performed significantly better (mean = 25.60, SD = 1.48) than aMCIs (mean = 18.21, SD = 1.58). Post hoc analysis showed that participants’ accuracy at the second fMRI session significantly differed on the 3 tasks (Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons), with performances on the CT better than those on the ET and AT (Figure 2D). Concerning the group-by-task interaction, post hoc analysis showed that the 2 groups (HC and aMCI) significantly differed in performing ET (P =.006) and CT (P = .006), with HC performing better than aMCI on these tasks (Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons) but without differences in performing AT (Figure 2D). Finally, the task-by-learning interaction showed that AT after AL was performed better than AT after EL (P = .007, Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons; Figure 2D).

The MCIs had a near-chance performance in both ET and AT, thus raising the suspicion that they might not be engaged at all in the tasks. To explore this possibility, we performed an analysis of the reaction time of the different type of possible answers. The rationale behind the analysis was that if the reaction times were modulated by the type of answer, and even more if this modulation was differentially present between the first and the second session, we could rest assured that, even in the presence of a significant amount of error, MCIs were indeed engaged in the task. In order to test this hypothesis, we divided the answers of the MCI participants into the 4 categories informed by the receiver operating characteristic (i.e., accepting a correct item, rejecting an incorrect item, accepting an incorrect item, and rejecting a correct item), and we performed a repeated-measure 4 × 2 ANOVA with factors (type of answer [true positive, true negative, false positive, false negative] and session [first vs. fifth day]). We found a significant effect of the type of answer (F 3,5 = 18.8, P < .001), as well as a significant effect of session (F 1,6 = 91.7, P < .001) and their interaction (F 3,5 = 20.5, P < .001). Interestingly, during the first session, patients with MCI were slower in accepting a correct item and rejecting a false item (i.e., answer correctly) than in rejecting a correct item and accepting a false item (i.e., committing an error). In the second session, the differences between the types of answers were no longer significant, and on average, participants with MCI were slower than during the first session. Our interpretation is that, since the first session, participants with MCI reached a certain degree of learning: items that were recognizable were observed for a longer time, and correct answers were emitted. During the second session, participants with MCI felt more secure and observed all the items for longer time, since they felt that they could produce the correct answer. As a whole, we think that the results of this analysis suggest that patients with MCI were engaged in the task, even if their accuracy was close to chance level.

Imaging

Region of interest analysis on fMRI data

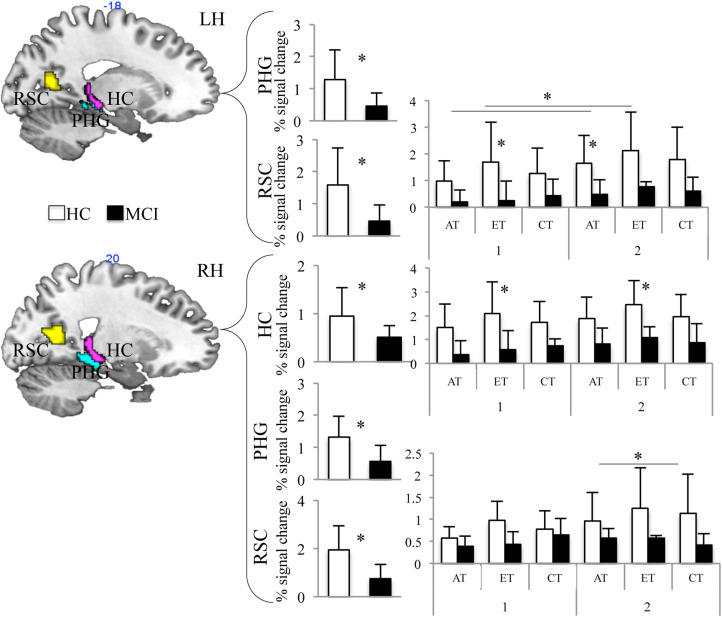

Region of interest analysis was conducted to assess the effect of group on BOLD activation in regions involved in topographical memory and spatial representation (i.e., hippocampus, PHG gyrus, and RSC) in different experimental conditions (session, task, and learning). Healthy controls showed significantly higher BOLD activation than aMCI within all selected ROIs (HC-RH: F 1,10 = 6.051, P = .034; PHG-RH: F 1,10 = 11.402, P = .007; PHG-LH: F 1,10 = 6.283, P = .031; RSC-RH: F 1,10 = 13.117, P = .005; RSC-LH: F 1,10 = 5.951, P = .035; see Figure 3) with the exception of the left HC. Furthermore, in the right HC, the group-by-task interaction was close to significance (F 2,20 = 3.534, P = .049). Even if with cautions, post hoc comparisons suggested that HCs showed significant higher BOLD activation than aMCI during the ET (P = .016, Bonferroni’s corrected for multiple comparisons; Figure 3). Interestingly, also the interaction group-by-session-by-task was close to significance (F 2,20 = 3.528; P = .049) in the left RSC. Post hoc comparison showed that HCs showed significant higher BOLD activation than aMCI during the ET in the first fMRI session (P = .039, Bonferroni’s corrected for multiple comparisons) and during the AT in the second fMRI session (P = .039, Bonferroni’s corrected for multiple comparisons; Figure 3). Left RSC also showed a significant session-by-task interaction (F 2,20 = 4.118; P = .032). Post hoc comparisons showed that BOLD activation was higher for the AT and ET during the second fMRI session (P = .039, Bonferroni’s corrected for multiple comparisons; Figure 3). Finally, the session-by-task interaction was close to significance in the right RSC (F 2,20 = 3.579; P = .047). Even if with cautions, post hoc comparisons showed that BOLD activation was higher during ET than AT and CT during the second fMRI session (P = .020, Bonferroni’s corrected for multiple comparisons; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Results of ROI analysis in HCs (white bars) and aMCIs (black bars) on the 3 experimental tasks performed in the first and second sessions. Percentage BOLD signal change in HC and MCI in the bilateral hippocampus (HC), parahippocampal gyrus (PHG), and retrosplenial cortex (RSC). aMCIs indicates patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairments; AT, allocentric task; BOLD, blood oxygen level-dependent; CT, control task; ET, egocentric task; HCs, healthy controls; MCI, patients with mild cognitive impairment; ROI, region of interest.

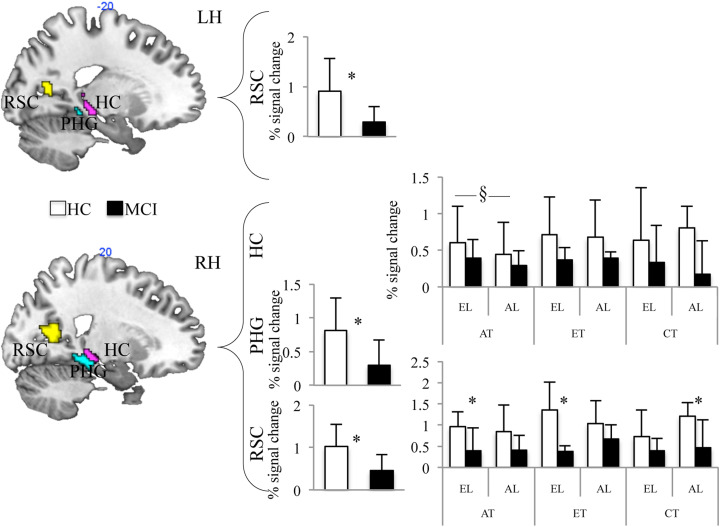

Then, we focused on the fifth day of training (second fMRI session), including learning (EL and AL) as a factor. We found a main effect of group in the right PHG (F 1,10 = 9.984; P = .025) and bilateral RSC (left hemisphere: F 1,10 = 5.958; P = .035; right hemisphere: F 1,10 = 10.025; P = .010), with HCs showing higher activation than patients with aMCIs (Figure 4). We also found a significant task-by-learning interaction in the right hippocampus (F 2,20 = 4.044; P = .034; Figure 4). Even if post hoc comparisons failed in finding clear significant differences, we would anecdotally report that the greatest difference among EL and AL has been observed during AT. Finally, the right RSC showed a significant task-by-learning-by-group interaction (F 2,20 = 3.621, P = .045). Post hoc comparisons showed greater activation in HCs as compared to aMCIs during AT of egocentric-learned path (P = .021), ET of egocentric-learned path (P = .002), and CT of allocentric-learned path (P = .007).

Figure 4.

Results of ROI analysis in HCs (white bars) and aMCIs (black bars) on the 3 experimental tasks performed in the 2 learning conditions in the second session. Percentage BOLD signal change in HCs and aMCIs in the bilateral hippocampus (HC), parahippocampal gyrus (PHG), and retrosplenial cortex (RSC). aMCIs indicates patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairments; AL, allocentric learning; AT, allocentric task; EL, egocentric learning; ET, egocentric task; CT, control task; HCs, healthy controls; MCI, patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment.

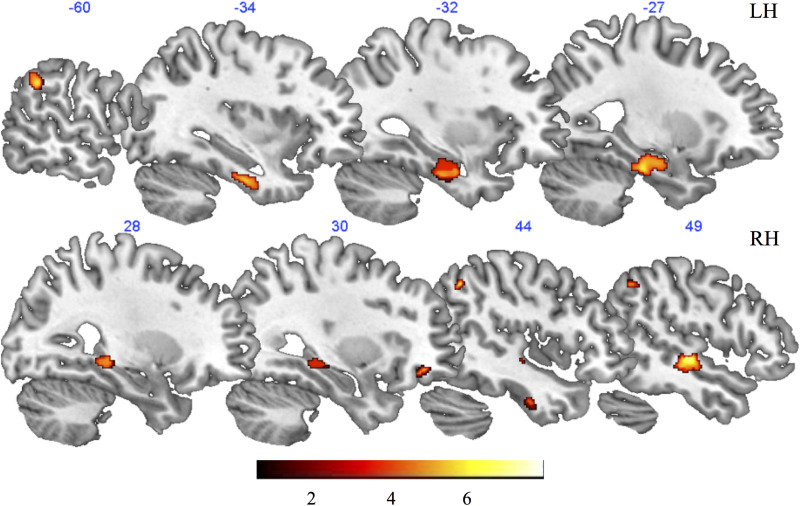

Voxel-based morphometry results

The 2-sample t test performed using the GM images of individuals with aMCI and HCs revealed a greater GM volume in HCs in the bilateral fusiform gyrus, left hippocampus, inferior parietal lobule, and inferior temporal lobe, as well as in the right PHG, middle and superior temporal gyrus, angular and supramarginal gyri, middle occipital gyrus, and orbitofrontal cortex (Figure 5). The results of such a comparison are not surprising, considering the previous literature about GM changes in aMCI (see for example 41,42 ).

Figure 5.

Results of the voxel-based morphometry analysis. Red-to-yellow patches depict regions showing greater gray matter volume in HCs compared to patients with aMCI, as it results from the 2-sample t test. aMCI indicates patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment; HCs, healthy controls.

Discussion

The present study was aimed to define the nature and neural correlates of topographical deficit in patients with aMCI. We expected to find a general decline in the navigational abilities of patients with MCI, related to hypoactivation of the cerebral navigational network.

Indeed, we found that patients with aMCI performed worse than HCs on topographical memory tasks, also after the intensive spatial learning, as it results from the analysis of their performances at the second fMRI session. The fMRI data suggest that this deficit is correlated with the hypoactivation of the brain networks involved in topographical memory and navigational abilities. For easiness of exposition, the discussion will be divided into subheadings.

Behavioral Correlates of the Topographical Memory Deficit in aMCI

Behavioral results from intensive spatial learning and retrieval sessions deserve feasible considerations about the nature of the deficit of topographical memory in pathological aging. First, we found that aMCI showed a reduction in the rate of learning on the AL, relative to the HCs. Otherwise, aMCIs’ performances on the EL did not differ significantly from those of the HCs. This result, even if with caution due to the nature of the different measures adopted in the present study (i.e., RTs for EL and accuracy for AL), suggests that aMCIs have a selective deficit in the acquisition of navigational information from an allocentric (that is, a map-like) perspective. Anyway, such a result is also strengthened by previous findings of a specific deficit in acquiring new allocentric spatial information in MCI. 5,32

Second, the behavioral results of retrieval sessions clearly showed that patients with aMCI had a selective impairment in retrieving topographical memory using an egocentric perspective, regardless the learning perspective (AL or EL). This would suggest that patients with aMCIs are not able to retrieve navigational information to deal with the ET, thought they are able to acquire new EL, as it is demonstrated by the results on the EL. This result is also consistent with the hypothesis of the deficit in the mental frame syncing for patients with AD advanced by Serino and Riva 34,35 and suggests that this deficit could be also present in prodromal stages of AD such as aMCI. Furthermore, patients with aMCIs performed worse than HCs on the CT. This effect could be due to the perceptual deficits, described in patients with AD as critical in determining navigational deficits in these patients. 7 Performances of patients with aMCI on the AT did not differ from HCs. It has to be noted also that the AT is the most difficult among experimental tasks, as it is demonstrated by the main effect of the task on accuracy both in this study and in the previous one with healthy young participants. 36

Concerning the lack of differences between HCs and aMCIs’ performances on the AT, feasible considerations are possible. Indeed, we found that HCs, at variance with patients having aMCI, significantly improved their performances across 5 days of training, increasing the number of correctly positioned postcards. On one hand, this result suggests that after intensive spatial training, healthy older adults are able to locate landmarks on a map, showing an increase in performances across days of training, different from what emerged from previous studies 3,4 that did not use intensive spatial training. On the other hand, the finding that HCs did not differ from aMCIs in AT, in spite of the improvement in learning accuracy during AL, suggests an early deficit in recalling a cognitive map of the novel environment, also in normal aging.

Neural Correlates of the Topographical Memory Deficit in aMCI

Results from the ROI analysis showed that patients with aMCI had hypoactivation of specific brain areas of human navigational network. 1 Actually, we found higher activation in HCs in the bilateral PHG and RSC as well as in the right hippocampus. Such a difference is also present after the intensive spatial training in the right PHG gyrus and RSC. These results strongly suggest that the deficit in navigational abilities and the resulting topographical disorientation in aMCIs are related to hypoactivation of the structures beyond hippocampal formation, such as the PHG and RSC, crucial in supporting topographical memories about new and old environments. 1,43

Interestingly, we found that the right hippocampus is less activated in the aMCIs during the ET, both in the first and second fMRI sessions. This could be the neural underpinning of the impaired performances during the ET. We also found that the left RSC is less activated in aMCIs during the ET on the first fMRI session and during the AT on the second fMRI session. This region is also globally less activated in the aMCIs in the second session, as demonstrated by the main effect of the group. Furthermore, the right RSC is significantly less activated in aMCIs in specific condition of retrieval: AT of EL, ET of EL, and CT of AL. Lower activations of the right RSC in aMCIs during ET of EL may be the neural underpinnings of the observed deficit of these patients (see also current behavioral data) in extracting directional information. Alternatively, lower activations during AT of EL in aMCIs may suggest lower recruitment of such a region in translating navigational information from a reference frame to another in these patients. This is also consistent with neuropsychological evidence for a deficit in egocentric topographical working memory in early AD. 44

Finally, lower activation of the right RSC in aMCIs during the CT of the AL could be related to the fact that participants were a little bit less familiar with the screenshot of the path they learned from the allocentric perspective because they saw them in a smaller format than that used in the ET. This can be particularly problematic for aMCIs, who may not generalize the topographical learning across different modalities. In other words, this effect seems to suggest that patients with aMCIs, although they are primed by the exposure to topographical stimuli (i.e., the CT of the EL path results in normal activation of the right RSC), showed lower activation of the right RSC when they looked at pictures of the acquired environment, failing in showing the expected activation of the RSC for the familiar environment 45 and observed in HCs for both AL and EL in the CT because of the format change. This is also in line with worse performance of aMCIs in such a condition.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In conclusion, aMCIs showed pattern of behavioral and neural responses that suggest a specific deficit in learning novel environment and generalizing acquired information to cope with a topographical memory task. The difficulty in recognizing the environmental pictures when the format in which they are presented is even slightly different from that they were displayed during learning, suggesting a defect in generalizing acquired environmental information, may affect also the capability to recognize landmarks and views when perceived from a different perspective (for example, when arriving in a square from a different way), a defect which could be, at least in part, responsible of the navigational and topographical deficits in daily life.

Analysis on GM volumes of individuals with aMCI and HCs showed a decreased volume of medial temporal lobe structures in aMCIs, as well as in the angular gyrus and orbitofrontal cortex. This result suggests that early atrophy in these structures could account at least in part for the decline of topographical memory in patients with aMCI, especially in forming new topographical memories from a map-like allocentric representation and in using stored egocentric knowledge to deal with a navigational task.

Taken together, the results demonstrate that the topographical memory deficit in aMCIs may be due to the hypoactivation of a set of areas necessary to form and use topographical memories. This deficit seems to be related to the acquisition of new allocentric information (AL), but it also encompasses the inability to use acquired egocentric knowledge to perform a topographical memory task (EL). Failing in finding a clear deficit in AT is probably due to the decline of this specific ability also in HCs. These results, taken together with those from previous studies5,7,26, suggest a continuum in the progression of topographical memory deficit from normal aging to MCI and AD. Anyway, aMCIs in the present study also showed a deficit in the visuoperceptual condition (CT), which can suggests that a deficit in visual perception, and in particular in the perception of a complex visual scene, is the basis for the general topographical impairment observed in the MCI group. Both behavioral and functional results point toward an early deficit, which may be the cause of the poor performance in this group, as well as, in a cascade of effects, the cause of the hypoactivation in the more high-level cognitive areas. Further investigations are needed to better understand this issue. In any case, the present results, taken together with a previous one finding a specific egocentric deficit in topographical memory in early stage of AD, strongly support the idea that navigational deficit is one of the prodromal symptom of aMCI and early stage of AD and point toward the importance of a neuropsychological screening, including the assessment of topographical memory in normal and pathological aging, to allow accurate and well-timed diagnosis and intervention.

Limitations

One of the major limits of the present study is the restricted number of participants, which prevents us from drawing any definite conclusions and flaws the generalization of the present results. Actually, due to the complexity of our paradigm and the amount of obligation required to our participants (5 consecutive days of training and 2 fMRI sessions), the present study did not allow for a high number of participants and it has been exposed to a great number of dropouts. Nonetheless, we believe that the novelty of our paradigm of intensive learning and the rigorous way in which we controlled for the representations involved during learning and retrieval make our results of interest. Further investigations with similar paradigms that optimize the training demanded may allow for the recruitment of higher samples—valuable for generalization of the present results.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: The online supplemental table is available at http://aja.sagepub.com/supplemental

References

- 1. Boccia M, Nemmi F, Guariglia C. Neuropsychology of environmental navigation in humans: review and meta-analysis of FMRI studies in healthy participants. Neuropsychol Rev. 2014;24(2):236–251. doi:10.1007/s11065-014-9247-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iaria G, Palermo L, Committeri G, Barton JJ. Age differences in the formation and use of cognitive maps. Behav Brain Res. 2009;196(2):187–191. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirasic KC. Spatial cognition and behavior in young and elderly adults: implications for learning new environments. Psychol Aging. 1991;6(1):10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilkniss SM, Jones MG, Korol DL, Gold PE, Manning CA. Age-related differences in an ecologically based study of route learning. Psychol Aging. 1997;12(2):372–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. deIpolyi AR, Rankin KP, Mucke L, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML. Spatial cognition and the human navigation network in AD and MCI. Neurology. 2007;69(10):986–997. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000271376.19515.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moffat SD. Aging and spatial navigation: what do we know and where do we go? Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19(4):478–489. doi:10.1007/s11065-009-9120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Monacelli AM, Cushman LA, Kavcic V, Duffy CJ. Spatial disorientation in Alzheimer’s disease: the remembrance of things passed. Neurology. 2003;61(11):1491–1497. doi:10.1212/WNL.61.11.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Byrne P, Becker S, Burgess N. Remembering the past and imagining the future: a neural model of spatial memory and imagery. Psychol Rev. 2007;114(2):340–375. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.114.2.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Siegel AW, White SH. The Development of Spatial Representations of Large-Scale Environments. Volume 10. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Academic Press; 1975:9–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Montello DR. A new framework for understanding the acquisition of spatial knowledge in large-scale environments. In: Egenhofer MJ, Golledge RG, eds. Spatial and Temporal Reasoning in Geographic Information Systems. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1998:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ekstrom AD, Arnold AE, Iaria G. A critical review of the allocentric spatial representation and its neural underpinnings: toward a network-based perspective. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:803. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aguirre GK, D’Esposito M. Topographical disorientation: a synthesis and taxonomy. Brain. 1999;122(pt 9):1613–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ruggiero G, Frassinetti F, Iavarone A, Iachini T. The lost ability to find the way: topographical disorientation after a left brain lesion. Neuropsychology. 2014;28(1):147–160. doi:10.1037/neu0000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iaria G, Incoccia C, Piccardi L, Nico D, Sabatini U, Guariglia C. Lack of orientation due to a congenital brain malformation: a case study. Neurocase. 2005;11(6):463–474. doi:10.1080/13554790500423602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iaria G. Developmental topographical disorientation: lost every day. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):745. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70133-9. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iaria G, Arnold AE, Burles F, et al. Developmental topographical disorientation and decreased hippocampal functional connectivity. Hippocampus. 2014;24(11):1364–1374. doi:10.1002/hipo.22317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iaria G, Barton JJ. Developmental topographical disorientation: a newly discovered cognitive disorder. Exp Brain Res. 2010;206(2):189–196. doi:10.1007/s00221-010-2256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iaria G, Bogod N, Fox CJ, Barton JJ. Developmental topographical disorientation: case one. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(1):30–40. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bianchini F, Incoccia C, Palermo L, et al. Developmental topographical disorientation in a healthy subject. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(6):1563–1573. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bianchini F, Palermo L, Piccardi L. et al. Where Am I? A new case of developmental topographical disorientation. J Neuropsychol. 2014;8(1):107–124. doi:10.1111/jnp.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Palermo L, Piccardi L, Bianchini F. et al. Looking for the compass in a case of developmental topographical disorientation: a behavioral and neuroimaging study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2014;36(5):464–481. doi:10.1080/13803395.2014.904843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosenbaum RS, Winocur G, Binns MA, Moscovitch M. Remote spatial memory in aging: all is not lost. Front Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:25. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2012.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maguire EA, Nannery R, Spiers HJ. Navigation around London by a taxi driver with bilateral hippocampal lesions. Brain. 2006;129(pt 11):2894–2907. doi:10.1093/brain/awl286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolbers T, Wiener JM. Challenges for identifying the neural mechanisms that support spatial navigation: the impact of spatial scale. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:571. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gazova I, Vlcek K, Laczó J. et al. Spatial navigation—a unique window into physiological and pathological aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:16. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2012.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hort J, Laczó J, Vyhnálek M, Bojar M, Bures J, Vlcek K. Spatial navigation deficit in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(10):4042–4047. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611314104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weniger G, Ruhleder M, Lange C, Wolf S, Irle E. Egocentric and allocentric memory as assessed by virtual reality in individuals with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(3):518–527. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rusconi ML, Suardi A, Zanetti M, Rozzini L. Spatial navigation in elderly healthy subjects, amnestic and non amnestic MCI patients. J Neurol Sci. 2015;359(1-2):430–437. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caffò AO, De Caro MF, Picucci L, et al. Reorientation deficits are associated with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5):321–330. doi:10.1177/1533317512452035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolbers T, Dudchenko PA, Wood ER. Spatial memory—a unique window into healthy and pathological aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:35. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Serino S, Morganti F, Di Stefano F, Riva G. Detecting early egocentric and allocentric impairments deficits in Alzheimer’s disease: an experimental study with virtual reality. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:88. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2015.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vlček K, Laczó J. Neural correlates of spatial navigation changes in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. 2014;8:89. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Serino S, Cipresso P, Morganti F, Riva G. The role of egocentric and allocentric abilities in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:32–44. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Serino S, Riva G. What is the role of spatial processing in the decline of episodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease? The “mental frame syncing” hypothesis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:33. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Serino S, Riva G. Getting lost in Alzheimer’s disease: a break in the mental frame syncing. Med Hypotheses. 2013;80(4):416–421. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2012.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boccia M, Guariglia C, Sabatini U, Nemmi F. Navigating toward a novel environment from a route or survey perspective: neural correlates and context-dependent connectivity. Brain Struct Funct. 2016;221(4):2005–2021. doi:10.1007/s00429-015-1021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183–194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Measso G, Cavarzeran F, Zappalà G. et al. The mini-mental-state-examination—normative study of an Italian random sample. Dev Neuropsychol. 1993;9(2):77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Friston KJ, Fletcher P, Josephs O, Holmes A, Rugg MD, Turner R. Event-related fMRI: characterizing differential responses. Neuroimage. 1998;7(1):30–40. doi:10.1006/nimg.1997.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–289. doi:10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Han Y, Lui S, Kuang W, Lang Q, Zou L, Jia J. Anatomical and functional deficits in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e28664. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meyer P, Feldkamp H, Hoppstädter M, et al. Using voxel-based morphometry to examine the relationship between regional brain volumes and memory performance in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:89. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nemmi F, Boccia M, Piccardi L, Galati G, Guariglia C. Segregation of neural circuits involved in spatial learning in reaching and navigational space. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51(8):1561–1570. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bianchini F, Di Vita A, Palermo L, Piccardi L, Blundo C, Guariglia C. A selective egocentric topographical working memory deficit in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: a preliminary study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014;29(8):749–754. doi:10.1177/1533317514536597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Epstein RA. Parahippocampal and retrosplenial contributions to human spatial navigation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(10):388–396. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]