Abstract

Introduction:

Social representations (SRs) contain 3 dimensions: information, attitude, and field. These affect the recognition of the first symptoms of dementia by the patient’s caregiver. This study focused on the period from the first signs of cognitive difficulties to the diagnosis of dementia.

Methods:

Eight caregivers of elderly patients with dementia were interviewed to construct their SRs regarding dementia and how this influences seeking medical treatment during the first stages of the disease. Social representations were analyzed through a structural focus, based on the content analysis.

Results:

Decision making is related to knowledge about dementia, attitude (emotions and sensitivity), and the concept of the caregiver about the relative with dementia. The results confirm the importance of the symbolic dimension of personal experience in managing care and seeking medical treatment.

Conclusion:

The presence of dementia in the family creates interpersonal dilemmas that caregivers experience. The solutions are framed in the sociocultural context.

Keywords: dementia, social representations, caregiving, Mexicans, qualitative

Introduction

The first signs of cognitive deterioration in the elderly patients generally create great concern among the members of the family. Their reactions vary from denial to an active search for information. 1 –3 However, little is known about the processes that relatives go through during the first stage of dementia. Health professionals and the caregivers themselves see a delay in the diagnosis of dementia as an issue of concern, because an early diagnosis is considered essential in improving the patient’s prognosis. 4

Diagnosis during the first stages allows the caregivers and the people affected by dementia to have time to understand what is happening, plan the future, and establish ties with health services to avoid crisis situations. 5 The evidence suggests that between 50% and 80% of patients with dementia are not diagnosed in primary care and many patients are lost because of a lack of a formal diagnosis. 6,7

Studies show a segmented vision of the caregivers’ experience, using stress, depression, and the burden carried in describing the caregiver’s experience. 2,3,7 –9 Some other studies consider a holistic approach, where multicultural dimensions are often lost or ignored. 3,7,10 –12

It has been noted that cognitive performance can decline up to 9 years before a diagnosis of dementia. 13 Nevertheless, some caregivers wait for up to 2 years before starting the process of diagnosis. 14 Most studies that analyze the first stages of the illness and its treatment refer to the barriers found when seeking care for the patient, which are factors that can delay utilization of health services. 15 Among those reported, the most common are perceived lack of financial resources, interpersonal difficulties, conflicts among the social actors (relatives, friends), fear of being judged by others, and the way health services are organized. 16 –20

Identifying and incorporating social representations (SRs) 21 into the different health areas offer a partial solution because they constitute a form of socially shared knowledge used to understand and explain the phenomena of daily life. They contain a functional dimension, not only because of the behavior they produce but also because they imply changes in the environment. They originate in a symbolic universe that is fundamental to the construction of social reality. The creation of these individuals’ social reality, culture, and relationship to nature, and at the same time the processes of interaction among individuals, allows us to understand the need for men and women to be aware of their. An SRs is not an introjection of external images. It constitutes an active construction rather than a passive reproduction. The SRs affects the individual and the collective creation of social reality by generating shared visions and similar interpretations of events; it attempts to understand the symbolic universe. Hence, an approach to groups and communities about the way they interpret dementia entails identifying the socially shared mental images that emerge to represent the person with dementia. We can establish and understand the relationships between society and people with dementia through the people that care for them. Knowing and understanding the SRs of family groups that include people with dementia will allow us to promote changes that enable the social reintegration of these people into their family units without discrimination from the rest of society, by turning the unknown into something familiar and the invisible into something noticeable.

Social representations, their creation, and transmission mechanism are important because they can be the cause of negative attitudes toward seeking help for the individual who shows signs of dementia. Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify the caregivers’ SRs regarding dementia in a family member and how awareness of SRs influences seeking treatment during the first stages of dementia as well as to describe the difficulties for the family in confronting the illness.

Methods

This study is part of the “Study on Aging and Dementia in Mexico” (SADEM). The SADEM was a cross-sectional study conducted to determine the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia, between September 2009 and March 2010. The methods have been reported elsewhere. 22 The data reported here were collected at end point. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by The National Commission of Scientific Research and by the IMSS Ethics Commission (registration number 2008-785-019). We used standard written consent procedures.

Participants

The participants were the primary caregivers of 8 adults aged 60 or older randomly selected from all adults (n = 100) with positive diagnosis of dementia from the SADEM study. These 8 patients were chosen from 8 of the 16 boroughs that make up Mexico City, in order to broach all social strata; in addition, the patients had less than 1 year from diagnosis and had not yet initiated formal treatment. (Currently, in Mexico, treatment of dementia uses some acetylcolinesterase-inhibiting drugs, such as donepezil, rivastatin, and galantamin, which have proven effective in the control of cognitive symptoms and which can improve functionality and of life. The patient is evaluated periodically for response to the assigned treatment.) The diagnosis of dementia was according to the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition). 23 Criteria are described in the original study. 22 Inclusion criteria of caregivers were to have remained with the patient from start of symptoms until diagnosis of dementia. Exclusion criteria for the caregivers were the presence of major depressive disorder or cognitive disorders.

Procedure

The caregivers were interviewed in their homes on only 1 occasion. We explained the purpose of the study to all participants and also asked them to give their consent for us to record the interviews for later transcription. We also informed them that they could end the interview at any time if they wished to and that doing so would not affect in any way the treatment for their affected relative. Interviews followed a semistructured format, lasting between 45 and 60 minutes. The aim of the interview was to identify the caregivers’ SRs regarding dementia in a family member and how awareness of this SR influences seeking treatment during the first stages of dementia as well as to describe the difficulties in confronting the relative’s illness. The terms “dementia” or “Alzheimer disease” were not used at any point unless introduced by the participant.

The interview began by obtaining sociodemographic data relating to the caregiver; after that the interview was designed to identify the elements of SRs. Each interview began with a number of open questions that approached spontaneous knowledge more easily. The interview focused on information regarding the caregiver’s understanding and general knowledge about dementia, the image of the patient, and the impact of the disease on the family. It included both personal and social questions (see attachment 1). We also investigated the way the caregiver contacted health services as well as the conflicts encountered and solutions found.

All participants referred directly to dementia or Alzheimer in this study, after which the interviewer would ask what this meant to the participant, how the diagnosis affected the caregiver and the implication of this diagnosis on everyday life, and how she felt about this. After concluding the interview, the participants were told that if they had any questions about the study they could contact the interviewer.

Analysis

All interviews were transcribed and processed using Atlas tI Software v 6.1.11 (ATLAS. ti., Version 6, Copyright 2003-2012; Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin).

Patient identity was protected using a pseudonym. We performed the analysis in stages. In the first one, we read each of the 8 interview transcripts thoroughly. From this review, we identified the codes (most frequent words or phrases) systematically to constitute thematic units, making key notes in the right margin of each transcript. Additional memos relevant to the aim of the study were also noted at this time. By doing so, we identified all themes, as well as the main concepts, using the participants’ own words. Each theme was considered to be a unit and was coded to interpret the meaning of the information obtained. Finally, we summarized, in a general list, all thematic units identified in the 8 interviews. In the second stage of the analysis, we grouped the concepts obtained in the first stage into categories, which we arranged in the order of importance, to establish relationships or connections between the different contents identified, which allowed us to identify patients that articulated the essential aspects of the results as a central phenomenon. The codes or concepts that did not appear in at least two-thirds of the interviews were eliminated from the analysis. Finally, we grouped the related concepts. This led to construction per the objective of the study by saturation of categories.

Credibility and Trustworthiness

Interviews were analyzed using statement semiotics, a method that results in a synthesis between cognitive semiotics and speech analysis, which guarantees the credibility and reliability of the analysis. Two different researchers can independently come to the same results, and the few disagreements were resolved by consensus. 24

Results

The participants in this study were women, daughters (80%) or wives (20%), with an average age of 55. The educational level for the caregivers interviewed was incomplete primary (20%), elementary school (10%) or higher (60%), with the highest being a bachelor’s degree in business (10%). Only 2 caregivers belonged to socioeconomic level type D (lower class), 3 to type D+ (lower middle class), 2 to type C (middle class), and 1 to type C+ (upper middle class). 25 In all, 50% were housewives, 20% had a steady job, 10% had a temporary job, and 20% were unemployed. Only 1 caregiver received financial support for the patient’s treatment. The time in months since assuming the care by each of the relatives interviewed had a mean value of 7.5, with a minimum of 6 and a maximum of 10 months.

First, a list was prepared of the words or phrases the interviewees mentioned, in order of hierarchy and according to the main categories described in Table 1. This range of information allowed the organization of the results of the research according to the thematic units for the construction of representations the caregiver has regarding dementia in a family member.

Table 1.

Most Common Words Obtained According to the Main Categories for Construction of Social Representations in Dementia.

| Category | % | Category | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | Care | ||

| Loss | 10 | Happiness | 10 |

| Death | 10 | Remorse | 10 |

| Frustration | 10 | Reciprocity | 20 |

| Desperation | 10 | Vocation | 20 |

| Distress | 10 | Incapacity | 20 |

| Neuronal damage | 20 | Attachment | 30 |

| Sadness | 30 | Searching for treatment | 30 |

| Identity | 30 | Education | 40 |

| Anger | 30 | Specialized services | 40 |

| Physician | 30 | Welfare | 40 |

| Imbalance | 40 | Being positive | 40 |

| Fear | 50 | Obligation | 50 |

| Danger | 60 | Specialists | 50 |

| Incurable | 60 | Looking to the future | 60 |

| Medication | 70 | Help | 70 |

| Stress | 70 | Loss of identity | 70 |

| Suffering | 70 | Need | 80 |

| Treatment | 80 | Feelings | 90 |

| Expensive | 80 | Family | |

| Illness | 90 | Making decisions | 10 |

| Loss of memory | 90 | Care | 20 |

| Old age | Search for treatment | 20 | |

| Death | 5 | Loneliness | 30 |

| Being positive about life | 10 | Lack of support | 40 |

| Doing exercise | 10 | Loss of bonds | 40 |

| Carelessness | 10 | Family rupture | 40 |

| A matter of attitude | 20 | Economy | 60 |

| Loss of the patient's functionality | 40 | Conflicts | 90 |

| A matter of getting old | 40 | ||

| Illnesses | 50 | ||

| Not being able to do anything | 60 | ||

| Natural process | 80 | ||

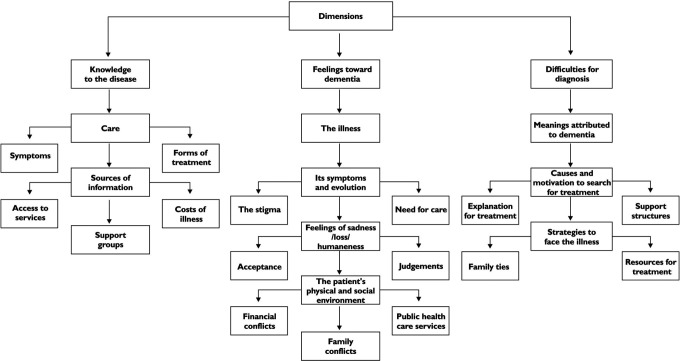

Analysis identified 3 central dimensions of the categories that gave rise to caregivers’ SRs regarding dementia in one of their family members. The dimensions that emerged were “knowledge of the disease,” “feelings toward dementia,” and “difficulties for diagnosis.” Each of the participants mentioned each of these issues. Figure 1 shows a list of each of the subtopics that gave rise to these final categories. Each higher order of categories is represented by related subthemes that were grouped together by similarity. The experiences reported by the caregivers account for each of these subthemes.

Figure 1.

Construction of dimensions in social representations through the speech of a relative in charge of caring for a family member with dementia.

Knowledge to the Disease

The dimension of information referring to knowledge about the relatives’ illness is based on the knowledge acquired by caregivers throughout their lives. This dimension is formed by 8 categories symptoms, the patient’s treatment needs, treatment options and procedures, sources of information, access to services, expenses derived from the illness, places to take the patient, and support groups.

This subject generally reflects how the participants understand dementia and its development. For the caregivers interviewed, dementia is identified by its effects on patient behavior, stressing the loss of the capacity to remember.

Examples: A: “[…] It’s a problem of his memory; he doesn’t remember what he does or what happened just yesterday” […]

C: “[…] I think obviously that it is her age; of course I have friends older than her and they have a very good memory” […]

The emotional component affects the caregiving experience: the need to return love, affection, and free help allows one to be patient, tolerant, dedicated, and more aware, to assume responsibility, these factors becoming determinants in the caregiver’s decision-making process.

Examples: E: “[…] Well, at best by caring” […]

F: “[…] Because I have always seen to her” […]

Once the disease is presented and patient care begins, some caregivers opt for seeking information. The resources most widely used by families to find out about the disease and its evolution are the Internet and media, always with the object of the best care for the patient.

Example: A: “[…] My daughter began to search on the Internet and realized that this disease exists” […].

Nevertheless, it was also noted that other caregivers did not feel the need to find out about the disease the family member presented and remained only with medical discussion on dementia.

Example: H: “[…] According to what the doctor explained, it is due to small cerebral infarctions, some parts of my mother’s brain are affected; it affects her memory” […].

Feelings Toward Dementia

We identified 9 categories for the dimension of feelings toward dementia: the symptoms and course of the illness, feelings of sadness/loss/humanism, stigma, need for treatment, physical and social environment of the patient, financial difficulties, public health services, and family problems. These subthemes express the values toward dementia and their effect on the social environment of the patient, and they demonstrate the destabilization suffered at the onset of dementia, which seriously affects life, both the patient and caregiver, who most often interrupts his or her own activities to devote himself or herself to the patient’s care and loses his or her own freedom because of a lack of support from the rest of the family.

Example: E: “[…] Yes, if I don’t leave her alone; what’s more, I am not happy if I’m not with her. I don’t let her go anywhere … plus I know she really needs me” […]

It has been found that the suffering of family members is intense. Once the diagnosis has been established, a range of emotions and sensations is detonated which moves from denial to acceptance of the disease of a family member. The patient suffers a loss of identity, feeling that he is a shadow of what he was and that he has now lost autonomy and has become an extension of the thoughts of the caregiver who now will make all his decisions for him.

Examples: B: “[…] Why did this come to her, no? Being a person, well, well at the time she was very active, mmm, yes!, that because she and, well, always her behaviour was very kind and she went helping everybody, eh, of course her family and all” […].

C: “[…] Well it scares me to come to this (laughs) to experience it is, I would prefer that, if a thing like this should come to happen to me, my children put me in a home, the fact of facing them, that they would have to fight so much with me” […].

It is important to point out that caregivers face a series of dilemmas about dementia that influence their view of the patient and the feelings and emotions about the disease of a loved one.

Example: E: “[…] If, if I can’t leave it alone, what’s more, if I’m not happy, if I’m not with her, I don’t let her go anywhere” […].

The narrations of the interviewed caregivers give us evidence of how the loss of memory in a family member is perceived as uncertain and unimportant at the start of dementia, which delays seeking a diagnosis of the disease.

Examples: E: “[…] Well, like, I understand that she goes on losing or, certain valves in her brain” […].

G: “[…] Sitting watching her doing various things, various times, she forgets to put this, for example, to cook some eggs on the stove” […].

The feelings of family members (sadness, pain, anger, frustration, remorse) are intense and often confused.

Examples: B: “[…] Why did this happen to her, no?” […].

E: “[…] Frustration, but not at the fact that I have to take care of her, but at the fact of seeing what the disease has done to a woman as complete as my mother was” […].

The discussions with the caregivers show us that the patient with dementia carries a stigma, first due to the symptoms, various behaviors that violate the patient’s normality and social life, and then because it is about a disease of unknown etiology.

This is expressed in negative attitudes and behaviors of rejection not only in the family environment but also the social one of people with dementia.

Example: F: “[…] The truth is it scares me a lot, because you hear the word dementia and you identify it with craziness, then this, the diagnosis really floors me” […].

So the social stigma toward dementia is linked to any other mental illness, where the social circle of the affected person takes an attitude of making the dementia invisible; among the most frequent paths of denial of the presence of dementia in a family member, normalization through trying to see others as similar and avoiding circumstances that would call attention to the patient’s differences.

Example: A: “[…] They see him as, people think that any people that have a neurological problem necessarily are crazy and it isn’t so, then there are people that look at him with pity, with fear because they hear so many things that one says and it probably is aggressive” […].

In short, this study allows us to see that the stigma that accompanies dementia is a consequence of its symptoms that consist in behaviors that don’t fit with the normal for the patient.

Difficulties in Diagnosis

The dimension of the difficulties for diagnosis is formed by 7 subthemes: meanings attributed to dementia, causes and motivations in seeking treatment, explanations for treatment, strategies for coping with the illness, resources for treatment, support structures, and family bonds. In this dimension, the caregivers’ statements reveal the meaning they attribute to dementia, and the causes for the patient’s need for care, the strategies the relative uses to care for the patient and to seek treatment, how difficult the illness appears and the course it follows, the impossibility of having access to experts, reducing the options for diagnosis and treatment because of the limited resources available.

In Mexico, IMSS is the largest institution to give medical care to salaried workers and their families; it is made up of 3 levels of care: family medicine units, general area hospitals, and specialty hospitals. Among these levels of care there is a reference and counterreference procedure for the patient according to the complexity of his health problem, procedure that is often too long. In general, the first level cares for 85% of the health problems, the second level 12%, and the third only 3%. The IMMS cares for 87% of the insured population of the entire health sector, which represents 50 million inhabitants in our country. It has a basic framework of medications for each level of care, the doctor being the only 1 authorized to prescribe; these prescriptions are supplied by the clinic or hospital’s pharmacy, if and when there is stock, if not, the patient should buy his medication with his own resources. 26

As in other countries, in Mexico, the geriatric physician is the medical specialty dedicated to the study of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the health problems of the elderly individuals; that is why in Mexico, the geriatric physician is the specialist that begins the process of the diagnosis of dementia through the evaluation of different instruments, and he begins the process of pharmacological prescription, although according to the interviewees the medications used in the treatment of dementia do not represent a cure for the disease.

Examples: G: “[…] I already made an appointment for my mother with a private geriatric physician, this doctor prescribed many medications and, well, the medicines he sent sat well with her” […].

A: “[…] There is no treatment for this disease” […].

C: “[…] They sent her a very expensive medicine that she had to take but we had to take her to the hospital, she turned grave” […].

The lack of public health services has been noted for care of this disease that generates mistrust in going for care, thus generating a delay in the diagnosis of the illness, and even then some caregivers refuse to seek specialized care for the sick person.

Examples: H: “[…] mm, my brothers and I asked ourselves what, what, what to do, […] what measures we were going to take, since in this case, well, the doctor has been a good person, the one who cared for her and oriented us, told us to put her in an institution to care for her, various people like her go there” […].

D: “[…] No, it’s very hard, again, this, taking account of everything that has to be spent on her, more than $3,500 pesos a month in medication… which means spending more than she receives from her monthly pension” […].

B: “[…] Well, the doctor told me that it didn’t matter because really Vartalon hasn’t been proven, that costs $500 a box that lasts a month hasn’t been proven to be so effective” […].

The caregivers indicated the lack of specialized places where a reliable diagnosis could be made, one that offers them all the information necessary to understand the disease and advice for caring for the needs of these patients as well as indicating the lack of places capable of receiving their patients.

Examples: E: “[…] of an association; we went to that association and they told us they couldn’t receive my husband until he had a diagnosis” […].

C: “[…] They told me to take her to a home, but where they would take her in, no, now here” […].

A: “[…] It’s like a kind of day care, like a kindergarten, except that it’s for people like my husband, they take them in at 8 or 9 in the morning till 3 or 5 in the afternoon, a thing like that nowadays the cost is very high at least for me, I right now can’t pay it” […].

Some ways to try to handle and confront dementia were identified, even when they were not always successful. Confronting the disease occurred once one understood the symptoms and that they are intimately related with emotional reactions before the diagnosis and changes that move toward the appearance of the disease.

Examples: B: “[…] We came to Nutrition and it started, of course they made some errors, but okay that happens to everyone, to begin with an error waiting so long for the appointment” ….

D: “[…] Then I attribute it to the fact that in a big way it is because there was a medicine that really is what she needs because I see it has maintained her” […].

C: “[…] At the time my mother, well, began to lose awareness more about us, it would make it easy to bring in a caregiver, a nurse, or a person specialized in older people, so they can take charge of giving her, her medicine” […].

The words of the interviewees indicate that with the disease in a family member, with the consequent social, economic, and individual needs, and as a consequence of the misinformation, family conflicts develop that generate a series of confrontations and feelings of rejection by the family member who is forced to accept the responsibility for the care of the person with dementia but without being the one to decide about the care of the patient.

Examples: E: “[…] is there is a problem support is only by mouth to want to do many things outside, but at the moment of practice, no, they don’t have, they don’t make the time, generating fierce arguments” […].

H: “[…] They have not cared for her, and between the two that are the furthest, they toss the ball from one to another, well, there is your close sister, she should take care of you! And the other.” […].

Our study indicates that the lack of resources generates a series of family conflicts and the caregiver expresses a feeling of frustration and helplessness and a great burden, both emotional and economic, in facing the disease.

Examples: D: “[…] Economically there is one of my brothers that is in a very strong economic position, and he, he wouldn’t have any problem maintaining her the rest of her life, if necessary, the others well, are so swamped with problems and that, with difficulty they would be capable of being able to contribute.” […].

E: “[…] It’s a problem never having money for anything except the medications they need or to take care or help me a little” […].

Caregivers that have good social relationships have a greater understanding of the needs for the care of their relative and reflect a feeling of comfort since they can handle their stress, express their doubts, and receive support.

Examples: G: “[…] The one who is giving us the support group, for families with Alzheimer, and in fact I already commented to my children, I say they should also know because, well, there is the fact that I’m going to need them to help me” […].

E: “[…] from an association, we went to that association and they told us they could take in my husband, and here the doctors explained to me with more detail and clarity what the disease my husband has is” […].

Explanatory Model

From the results and based on the SRs, an explanatory model was created, which suggests that dementia appears for caregivers as an autonomous living entity that melds experiences and feelings generated by compassion for the diseased person, whose effects and consequences vary depending on the context in which they are produced. Figure 1 shows this model as “knowledge of the disease,” “feelings about dementia,” and “difficulties in diagnosing,” determined by the ability of the caregiver to understand the presence of dementia as a disease, leading to awareness of the need for care for the affliction and the afflicted. The mechanisms of confronting referred to in the discussion with interviewees demonstrate that it is the family that delays searching for care, lengthening the period for detection of the disease by confusing it with the signs of aging, so a barrier arises for seeking care; added to this the caregivers denounce the lack of available health services to evaluate the presence of the disease and their need to turn to private medical services that, for financial reasons, they have to suspend, generating a feeling of guilt in the caregivers for not being able to offer quality care for the patient.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the SRs of 8 relatives devoted to taking care of a family member with dementia. To do so, we identified their beliefs, values, attitudes, and discursive forms in order to show their influence on seeking treatment during the first stages of dementia; we also identified the strategies followed by the family to face the relative’s illness. These representations show an area where the caregiver is exposed to a mixture of messages, values, and beliefs that can either paralyze or guide his or her actions.

We can explain these SRs using each person’s history of learning about dementia, which determines the way he understands it and the way he seeks treatment for this illness. The perception constructed as a scheme following a prototype should allow us to identify tools that will protect caregivers.

The female gender (daughters or wives) was the only one involved in this study, stating various aspects that motivated them toward care. When caring for a mother, the sense of duty dominated, with a moral obligation and reciprocal feelings acquired over a lifetime. While in the case of spouses, the values and loyal behavior were acquired at the time of marriage, reinforced by love; these were the reasons that motivated care. This shows that care is assigned socially to the female gender, at least in the Mexican culture, where most men have grown up in a household and certainly a culture in which females have been perceived as the primary family nurturers. The male caregivers are more likely to be victims of caregiver stigma, since it is the women who receive the obligation to care for a vulnerable member of the family, in this case, the patient with dementia, whether by her own choice or imposed. 27 Nevertheless, there are very few studies regarding male family members as caregivers, both in our country and worldwide.

We are aware that for care among the available people in the family, the choice falls in the majority of cases on a woman, in various countries and sociocultural contexts. Nevertheless, care is not only a question of women but also a matter for men, women, families, and society. 28

Men traditionally worry about the care of a mate only when there are no women to do it, and so this deals with an older subgroup among caregivers who have different characteristics regarding caregivers who have more obligations to meet than just care. 29

Yet, often as the number of mature adults continues to increase, there is added need for male caregivers for their parents and other family members. Emotions are generated as a result of caring for the person with dementia, especially pain and despair. This despair permeates the relationships established between the patient and the caregiver. Other feelings also became evident, such as distress or fear about the course of the illness, and a feeling of guilt when caregivers find themselves helpless to ease the patient’s suffering, as well as their own.

We perceive a positive attitude in the family when faced with having a member who is suffering from dementia in having to take responsibility for his or her care, without considering the possibility of sending the patient to a nursing home or a facility other than the patient’s home, in spite of the conflicts that interfere with family union or living together in harmony.

This study shows that the time between the diagnosis of dementia and the time the caregiver assumes responsibility does not determine early seeking of care, in order to avoid the negative effects of the disease on the patient. This allows us to understand the origin of this phenomenon and so allows us to establish some predictive factors within the social and cultural context of the group. Previous knowledge, attitudes, family, and economic support determine the connection between these phenomena. This allows us to suggest new studies to delve into each of the aspects, considering a greater power for the sample analyzed.

This is of great relevance for the caregiver and the patient’s life, and at the same time delays seeking treatment, because it is considered a common process of deterioration among the elderly, and it is culturally perceived that the family unit must care for the elderly.

The SRs existing in the family are reinforced by life experiences affecting the information obtained, which is assimilated depending on the available scheme of every member, usually resulting in every need of the patient worsening the problems in the family dynamics. This in turn affects the course of the disease. Accepting that the family member is suffering from an illness, and seeking treatment depends not only on the caregivers’ knowledge but also on their social relationships and responses within the family unit and its social networks.

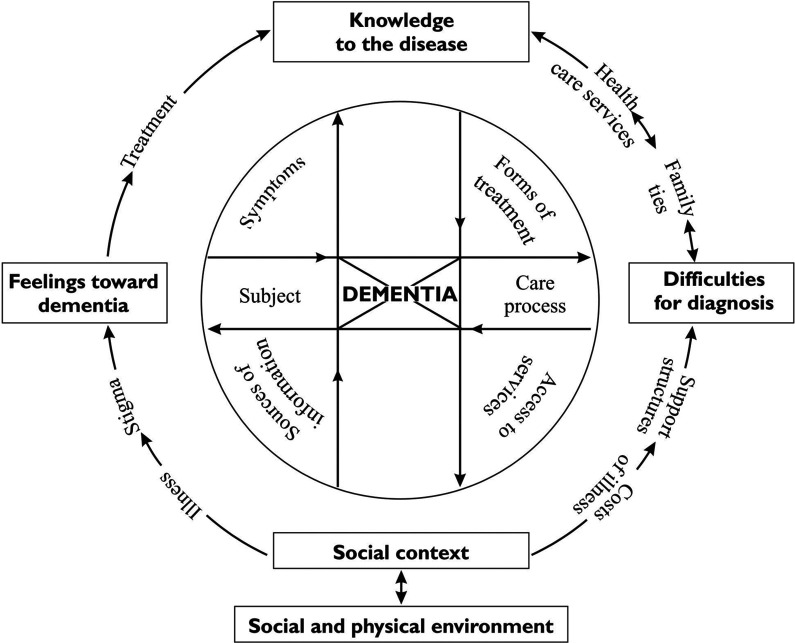

In this SRs, dementia is a category that joins experiences and feelings that are based on compassion for the patient in the face of the effects and consequences of the illness. Thus, dementia is seen as a living autonomous entity whose effects vary, because this conditions the cognitive assessment of the situation by the caregiver as well as contributing to other stressful factors, independent of the suffering that conditions seeking attention during the first stages of the illness (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Dynamic intergration between central category, dimensions, and subdimensions.

As a living entity, its capacity to impose itself not only on the patient’s life but also on the family stands out, because of the suffering and pain, rejection of the illness and fear that the patient will be excluded from his or her social environment, along with the loss of different life areas (work, family) in which the patient participated, making it impossible to plan a life project and altering the family economy.

We must emphasize the importance expressed in SRs of dementia related to the family conflicts that arise, because the onset of dementia creates new conflicts and aggravates those already existing among family members, which makes seeking treatment more difficult in view of the lack of agreement over the action to be taken.

All of this allows us to identify diverse SRs that share common elements to form a model. Therefore, we recognize a shared knowledge, with variants that depend on the schemes and attitudes of each caregiver. This offers a possibility for deepening knowledge of certain practices and strategies, which can change the caregivers’ behavior. A relevant aspect that must not go unnoticed is the lack of support resources (places to take their patients, associations and self-help groups) for caregivers and patients with dementia.

Finally, we should highlight the way in which health care institutions respond. To begin with, most general practitioners are not equipped to recognize early signs of cognitive impairment and thus do not feel prepared to treat the patient. 30 We found a sense of isolation in the caregiver, and he tends to seek treatment from private health care services, which in turn is not feasible because of the lack of financial resources. The current state of public health care institutions explains the numerous difficulties in treatment and care for people having dementia, which is why the caregiver needs help in acquiring the skills to deal with a close relative with dementia.

It is important to point out that new studies are needed to explore these findings in different stages of dementia, to understand the changes in strategies that caregivers follow over the time of the disease, and what the mechanisms are that give better results in the search and care to control cognitive symptoms as the disease progresses that can improve functionality and quality of life.

One limitation of the study due to the small simple size is the representativity of the results, but it should be taken into account that the interest in this study centers on discovering meanings or reflecting multiple realities and social situations in the problem of family caregivers seeking care in the first stages of the dementia, which allows us to develop new hypotheses that may be generalized to other populations. Therefore, new research is needed that involves a greater sample size and that will allow the inclusion of other groups for comparison. 31

Conclusion

The presence of dementia in the family creates interpersonal dilemmas that caregivers experience when they recognize the changes imposed by the illness. These dilemmas create tension for both patient and family.

The solutions are framed in the sociocultural context, such as trying to understand or avoid thinking of the illness, in relation to decisions made. Also, the interaction between dysfunction, family problems, and overprotection by family members can either aggravate or reduce negative expressions by caregivers.

Appendix

Social Representation of Dementia and Its Influence on the Search for Early Care by Family Member Caregivers

Instrument For Gathering Information

What is the disease your family member has?

For you, what is this disease?

From whom or where did you get information about the disease?

What do you think about what your relative has?

Why do you think your relative needs to be cared for?

For you, which emotions does this provoke or produce (sadness, pain, suffering, sense of loss, etc)… How?…why?

If you had to describe your relative, imagining a tree, how would you describe him?

How do you think your life will be affected by your relative’s life?

Have you thought what will happen with your relative with his disease in a few years?

Do you think your relative’s disease will affect his life?

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by grants from SSA/IMSS/ISSSTE-CONACYT (Mexico) Salud-2007-01-69842 and the fund for the Promotion of Health Research, Mexican Institute of Social Security, FIS/IMSS/PROT/G09/772.

References

- 1. Adams KB, Sanders S. Differences in dementia caregivers’ experience of loss, grief, and depression in three stages of Alzheimer’s disease: a mixed-method analysis. Paper presented at the 8th Annual Conference of the Society for Social Work and Research; 2004; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ajit S, Lindesay J. Cross-cultural issues in the assessment of cognitive impairment. In: Burns A, Levy R, eds. Dementia. London: Chapman & Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gaugler J, Davey A, Pearlin L, Zarit S. Modeling caregiver adaptation over time: the longitudinal impact of behavior problems. Psychol Aging. 2000;15(3):437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rebekah P, Clare L, Kirchner V. It’s like a revolving door syndrome’: professional perspectives on models of access to services for people with early-stage dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(1):55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vernooij Dassen MJ, Moniz Cook ED, et al. Factors affecting timely recognition and diagnosis of dementia across Europe: from awareness to stigma. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leifer BP. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: clinical and economic benefits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5 suppl dementia):S281–S288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malaz B, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):572–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Waelde LC, Thompson L, Gallagher Thompson D. A pilot study of a yoga and meditation intervention for dementia caregiver stress. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60(6):677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roth D, Haley W, Owen J, Clay O, Goode K. Latent growth models of the longitudinal effects of dementia caregiving: a comparison of African American and white family caregivers. Psychol Aging. 2001;16(3):427–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marwit S, Meuser T. Development and initial validation of an inventory to assess grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontologist. 2002;42(6):751–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vitaliano P, Russo J, Young H, Teri L, Maiuro R. Predictors of burden in spouse caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease. Psychol Aging. 1991;6(3):392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meuser TM, Marwit SJ. A comprehensive, stage-sensitive model of grief in dementia caregiving. Gerontologist. 2002;41(5):658–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paun O, Farran C, Perraud S, Loukissa D. Successful caregiving of 67 persons with Alzheimer’s disease: skill development over time. Alzheim Care Q. 2004;5(3):241–251. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amieva H, Jacqmin Gadda H, Orgogozo JM, et al. The 9 year cognitive decline before dementia of the Alzheimer type: a prospective population-based study. Brain. 2005;128(pt 5):1093–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wackerbarth SB, Johnson MM. The carrot and the stick: benefits and barriers in getting a diagnosis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(4):213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kasper JD. Health-care utilization and barriers to health care. In: Albrecht GL, Fitzpatrick R, Scrimshaw SC, eds. The Handbook of Social Studies in Health and Medicine. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2000:323–338. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Millman M. Access to Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carpentier N, Ducharme F. Support network transformations in the first stages of the caregiver’s career. Qual Health Res. 2003;15(3):289–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pescosolido BA. Of pride and prejudice: the role of sociology and social networks in integrating the health sciences. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47(3):189–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carpentier N, Ducharme F. Care-giver network transformation: the need for an integrated perspective. Ageing Soc. 2003;23(4):507–525. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abric JC. Representaciones sociales: aspectos teóricos y metodología de la recolección de las representaciones sociales. In: Abric JC, director, Prácticas sociales y representaciones 2001. México: Ediciones Coyoacán; 2001:11–32, 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Juarez Cedillo T, Sanchez Arenas R, Sanchez Garcia S, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and its subtypes in the Mexican population. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;34(5-6):271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. American Psychiatric Association. Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales. DSM-IV. Barcelona, Spain: Masson; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Magariños de Morentin J. Manual Operativo para la aplicación de la Semiótica de Enunciados. OPS, Programa Mujer, Salud y Desarrollo; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25. López Romo Heriberto, Nivel Socioeconómico AMAI, Comité Niveles Socioeconómicos AMAI/Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales SC; http://www.amai.org/NSE/NivelSocioeconomicoAMAI.pdf Accessed September 8, 2013.

- 26. Información Institucional, IMSS; http://www.imss.gob.mx/instituto/Pages/index.aspx Accessed July 20, 2013.

- 27. Fromme EK, Drach LL, Tolle SW, et al. Men as caregivers at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(6):1167–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61(1):P33–P45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical Elath? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129 (6):946–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaduszkiewicz H, Zimmerman T, Van den Bussche H, et al. Do general practitioners recognize mild cognitive impairment in their patients? J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(8):697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hammersley M, Atkinson P. El diseño de la investigación; problemas, casos y muestras. In: Hammersley M, Atkinson P, eds. Etnografía: Métodos de investigación. Barcelona, Spain: Paidós; 2001:40–68. [Google Scholar]