Abstract

Approximately 36 million people have Alzheimer’s disease worldwide, and many experience behavioral issues such as agitation. The purpose of this study was to investigate the perceptions of long-term care (LTC) staff regarding the current use of nonpharmacological interventions (NPIs) for reducing agitation in seniors with dementia and to identify facilitators and barriers that guide NPI implementation. Qualitative methods were used to gather data from interviews and focus groups. A total of 44 staff from 5 LTC facilities participated. Findings showed that both medications and NPIs are used for the management of agitation. The use of NPIs was facilitated by consistency in staffing, and the ability of all the staff members to implement them. Common barriers to NPI use included the perceived lack of time, low staff-to-resident ratios, and the unpredictable and short-lasting effectiveness of NPIs. This study offers insight into perceived factors that influence implementation of NPIs and the perceived effectiveness of NPIs.

Keywords: dementia, agitation, nonpharmacological interventions, seniors, long-term care

Introduction

In 2010, it was estimated that more than 36 million individuals had Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or related dementias worldwide. 1 In the United States, 47% of long-term care (LTC) residents were reported as having some form of dementia. 2 The progression of dementias is typically accompanied by an increased need for assistance with basic daily function as well as alterations in an individual’s behavior. Such changes are due to a combination of neurological impairments, variations in an individual’s relationships and interactions, and a deterioration of their coping mechanisms. 3 Behavioral issues such as agitation and the increased need for more complex levels of care related to disease progression pose significant challenges to LTC staff. 4

Ninety percent of individuals with dementia exhibit behaviors of agitation and passivity at some point during the course of the disease progression. 5 In LTC facilities, agitation is often expressed as restlessness, pacing, cursing, constant requests for attention, and repetitive questions. 5 The type of agitated behavior is dependent upon the interaction among individual’s personality traits, medical conditions, and environmental and psychological factors. 6 Confusion, discomfort, and unmet needs also may underscore agitation, but the outward behavioral expression is usually the result of a need not being addressed. 7

Agitation can be managed using both nonpharmacological and pharmacological means. Nonpharmacological interventions (NPIs) are used to address the unmet needs of the agitated individual and to avoid the drawbacks of pharmacological interventions such as medication interactions and side effects. 8,9 Examples of commonly reported NPIs include music, 10–12 physical activity, 13,14 horticulture, 15 hand massage, 12,16 multisensory rooms, 17,18 and pet therapy. 19,20 As a heterogeneous practice, NPIs are often grouped into broad categories such as environmental, behavioral, sensory, physical, social, structural, psychotherapeutic, and combination interventions in the literature. 21,22 For the purpose of this study, the term NPIs was used to encompass all the interventions within the different categories. There is limited consensus on how to appropriately choose the most suitable intervention 23 when managing behavioral issues.

Regardless of intervention type, NPIs must be targeted to the resident’s specific needs, preferences, 8,24 and functional abilities. 14 Personalizing instructions to residents’ abilities promotes a sense of autonomy, self-esteem, and respect which enhances residents’ feelings of safety and security. 24 The NPIs may also be used to postpone the use of medications or in conjunction with medications to minimize their frequency and dose. The most comprehensive systematic review of NPIs was completed by Livingston and colleagues. 25 It included 162 studies of NPIs for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Based on the reviewed studies, music therapy, snoezelen therapy, and behavioral management techniques received strong recommendations. Further, psychoeducation techniques for caregivers were shown to be beneficial for modification of interactions with the patients. 25 It should be acknowledged that few NPIs have shown significant reduction in behavioral issues, and the quality of such studies is limited. 21,25 Therefore, further research is necessary to strengthen the support for the use of NPIs.

Pharmacological intervention is an alternative to NPIs, often given “as needed,” to calm the agitated individual. Polypharmacy, particularly related to chemically induced sedation, is a common concern and not without controversy. Individuals with dementia are frequently prescribed cholinesterase inhibitors, antidepressants, antipsychotics, or anticonvulsants to treat behavioral symptoms related to dementia. 26 Effective medications for agitation include risperidone and olanzapine, which are both atypical antipsychotics. 27 Bell and colleagues 28 found risperidone, olanzapine and citalopram to be the most commonly administered medications that had a sedating effect on residents in LTC facilities in Finland. Medications may minimize disruptive behavior, but for individuals with compromised communication ability, they may also conceal the need by stopping the behavior used to signal that need. 21 Overall, evidence for the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment for agitation is limited. 29,30 Side effects of medications used for agitation may include stroke, 27 decreased cognitive function, increased urinary tract infections, abnormal gait, 31 and paradoxically increased agitation. 32

Recommendations for treating behavioral issues in those with mild to moderate dementia 33 state that NPIs should be considered first or in combination with pharmacotherapy. Although the evidence is limited, music, snoezelen, bright light therapy, reminiscence therapy, and massage and touch therapy are recommended. 33 Similarly, clinical practice guidelines for severe AD22 state that in managing behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia, an assessment should be completed and identified symptoms should be targeted. When safety is not a threat to any person involved, NPIs should be the first line of treatment, with music and multisensory interventions receiving special mention. 22

Lewis and colleagues 34 examined the barriers and facilitators to implementing recommendations from guidelines into clinical practice. Approximately one-third of the barriers were structural such as resources, staff, and specific services, followed by organizational issues such as communication. The key facilitators for guideline implementation were education and standardized practices on an organizational level.

Despite the availability of guidelines supporting the use of NPIs in clinical practice and research on the effectiveness of individual NPIs, the topic on how staff in LTC perceive and use NPIs is sparsely explored. Knowing staff perceptions would not only inform the translation of knowledge and wider implementation of guidelines in LTC facilities but may offer valuable insights into the feasibility and resources necessary for NPI adoption. The purpose of this study was to investigate the perceptions of LTC staff regarding the current use of NPIs for reducing agitation in residents with dementia and to identify facilitators and barriers to NPI implementation.

Method

This cross-sectional qualitative study design was guided by Van Manen’s hermeneutic phenomenology, a methodology used to explore the lived experience of a phenomenon. 35 This methodology establishes a sense of understanding and meaning of experiences by highlighting details that are often taken for granted. 36 We investigated the perceived experiences of LTC staff relative to agitation of residents with dementia. The perceptions and knowledge about NPIs among the LTC staff were captured using focus groups, semistructured interviews, and a NPIs questionnaire. Focus groups were the main method of data collection, but interviews were used in circumstances where a position within LTC was filled by only 1 individual. The NPIs questionnaire allowed for the gathering of unbiased opinions about NPIs and increased the credibility of the data. These varied methods of data collection were selected to benefit from the participants’ differing scopes of practice, limit power differentials, and minimize bias.

Convenient sampling was used to enroll the LTC facilities into the study. Facilities were approached if they had at least 1 secured dementia unit and were located within the city limits. Sites were added throughout the study until saturation was reached. Three facilities declined participation due to competing priorities. At study completion, staff from 5 LTC facilities participated in this study. One facility was privately funded and 4 were publically funded. Of the 5 units, 3 were LTC homes with secured dementia units, 1 was a care home devoted to individuals with AD or related dementias, and 1 was a LTC unit within a rehabilitation hospital. The number of residents ranged from 12 to 36 per unit. The study protocol was reviewed with the unit coordinator or director of care (DOC) at each facility, and staff were invited to participate in the study through these gatekeepers. The research team extended the opportunity to participate to staff who met the following inclusion criteria: working on the specialized dementia unit or managing/overseeing a dementia unit, having been employed more than 3 months at the participating facility, and being fluent in English. A total of 44 LTC staff members participated (range 7-11 per facility). These included 8 registered nurses (RNs), 13 registered practical nurses (RPNs), 8 personal support workers (PSWs), 6 recreation specialists or coordinators, 3 DOCs, 2 unit coordinators, a recreation assistant, a resident assessment instrument coordinator, a dietary specialist, and an art therapist. In all, 98% of the staff were women, 26 (59%) worked full time, and 18 (41%) worked part time. The majority (75%, n = 33) worked day shifts; 6 (14%) worked only in mornings, 2 (4%) only in afternoons, and 3 (7%) only in evenings. In all, 57% of the participants had 11 or more years of experience in their current position. Five focus groups, with 4 to 9 participants per group, and 12 interviews (2 to 3 per facility) were conducted. The diversity of participants was an opportunity to gain a more comprehensive understanding of agitation prevention and management in LTC. Because the methods for reducing agitation could be implemented by staff from varying disciplines, this diversity was seen as important contributor to understanding the use of NPIs.

A customized NPIs questionnaire captured participants’ awareness of various NPIs and whether or not they implemented NPIs on units where they worked. The questionnaire was completed at the start of each focus group or interview session to capture unbiased perceptions of each participant and to prevent the influence of others in the focus group. The questionnaire included a list of 20 NPIs; beside each NPI was a column labeled “awareness of NPI” and another “use of NPI.” Each participant indicated in writing using an “X” for no or “√” for yes whether they were aware of or used the NPI (see Table 1). The NPI list was based on practice guidelines created by Buettner and Fitzsimmons 37 and was modified to include additional NPIs that were discussed in the literature 9 for the management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The provided list of NPIs was in no way exhaustive, and therefore, spaces were provided at the end of the questionnaire to include any additional NPIs that the participant was aware of or used. Each participant gave written consent prior to data collection. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Western University Research Ethics Board.

Table 1.

Excerpt With Examples From the NPI Questionnaire.a

| NPI | Aware of NPI | Use NPI |

|---|---|---|

| Calming music | √ | × |

| Physical activity | √ | √ |

| Pet therapy | √ | √ |

| Reading groups | √ | × |

| Reminiscence therapy | × | × |

| Are there any other NPIs that you are aware of that are not listed in the table above? If so, list them | ||

| Are there any other NPIs that you use that are not listed in the table above? If so, list them. | ||

Abbreviation: NPI, nonpharmacological intervention.

a “X” indicates that the participant was unaware or did not use the NPI; “√” indicates that the participant was aware of or used the NPI.

Krueger and Casey’s 38 focus group guide was used to establish the focus group and the interview protocols. Two complementary theoretical models, Kong’s 39 model of Antecedents and Consequences of Agitation and Algase and colleagues 40 Need-Driven Dementia-Compromised Behaviour Model, were used to create focus group and interview guides. These 2 models ensured that the questions addressed the entire range of processes including the internal and the outward expression of agitation, which individuals were influenced by the agitation, and the impact of the behavior on the staff and residents. All questions were phrased generally to enable participants’ freedom of expression when discussing specific topics, for example, “What influences your decision to use or not use NPIs when a resident is agitated?” “What do you see as the triggers to agitated behavior?” or “Please describe the role of NPIs in your typical work day.” Probes such as “Please elaborate on that…” were used to further explore emerging topics.

All focus groups and interviews were held at the LTC facilities to optimize recruitment and participation. Interviews were held with management (DOC, unit coordinators), the recreation specialists, and the art therapist. Interviews lasted approximately 1 hour each. Focus groups were conducted during lunch hour thus limited to 45 minutes. Each session was digitally audio-recorded. The first author (SJ) and a research assistant conducted all focus groups and interviews to ensure consistency among sessions. The research assistant kept written notes about the setting, group dynamics, and dominant discussion topics. As recommended in the literature, 41 the first author kept a reflective journal to acknowledge her perceptions and experiences. The journaling was helpful in the analysis of data and interpretation of the study findings.

Member checking was completed in 2 ways. First, at the end of each focus group session the research assistant summarized major discussion topics on a white board and asked participants to provide feedback to ensure accuracy. Second, transcripts of interviews were mailed to interviewers with a request to provide their feedback within 2 weeks. Data collection took place between January and April 2010, in Southwestern Ontario, Canada.

Data analyses commenced after the completion of the first focus group and interview and continued in parallel with data collection until saturation of themes was reached. Digital audio files of the focus groups and interviews were transcribed verbatim and organized using the NVivo8 software. To establish a draft coding scheme, 1 randomly selected focus group transcript was read independently by 3 coauthors (SJ, AZ, and MK). The initial list of codes was discussed by the group and modified to establish consensus. Then, 2 researchers (SJ and AZ) used another randomly selected interview transcript to refine the codes. Under the close supervision of the second author, the final coding list was used by the first author (SJ) to complete the sentence-by-sentence coding and the inductive analyses of all transcripts. Throughout this process the first author engaged in weekly reflection discussions with the coauthor. This reflexivity was used to minimize biases that any 1 person may have held prior to or during the study. Responses from the demographic questionnaire and the NPI questionnaire were analyzed using descriptive statistics and frequency analysis.

To ensure rigor, the researchers addressed trustworthiness through credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability. 42 Data was deliberately collected from various independent sources and through several means. 43 Member checking was used to confirm the accuracy of raw data addressing credibility. 42,44 Conformability was achieved through discussions between research team members during the analysis and interpretation of results. Strict adherence to the data collection protocols and audiotaping the sessions ensured dependability.

Results

The results from the NPIs questionnaire, the focus groups, and the interviews were converged and are presented here according to 4 main themes that emerged from the content analysis. The themes were perceptions of agitation, knowledge and the use of NPIs, agitation management with medications and NPIs, and facilitators and barriers for the implementation of NPIs in LTC.

Perceptions of Agitation

The first theme reflects participants’ perceptions of agitation as a problem. Agitation in varying degrees was perceived to be exhibited by persons with dementia on all secured dementia units by all study participants. The nursing staff and PSWs found agitation to be burdensome due to its interference with staff helping residents to efficiently complete daily care tasks. The displays of agitation varied and were summarized by a DOC, “… it can be either verbal agitation or physical aggression and it changes very quickly…” Nonphysical acts, such as wandering, were also noted. Agitation was most prevalent during bathing, mealtimes, afternoon shift change, and early evening hours. Perceived triggers of agitated behaviors included the environment (eg, noise, level of commotion, and lighting), other residents, boredom, confusion, over or understimulation, unmet physical needs (eg, hunger, pain, fatigue, and urinary tract infections), inability to express emotions (eg, feeling unsafe, desiring human interaction and compassion), and difficulties in finding words to clearly communicate. A recreation staff member identified times of transition as a trigger: “… Agitation also occurs when our programs are done… We [recreation staff] have kept them busy, they [residents] feel comfortable, they have the reassurance that they are OK, they know what’s going on and all of a sudden the program is over. Now, what do you do [to maintain that sense of control]?” Staff perceived that agitation was frequently caused by several simultaneously occurring triggers that were considered interactive and cumulative. A unit manager explained, “… you have 36 people living in close proximity and [residents] don’t know when they need a break from [the environment, other residents, noise, etc.].” Although staff saw triggers as modifiable, the staff was unable to individually minimize triggers for each resident due to competing job responsibilities. Therefore, staff reported that they decided daily how to respond to the agitation.

Knowledge and Use of NPIs

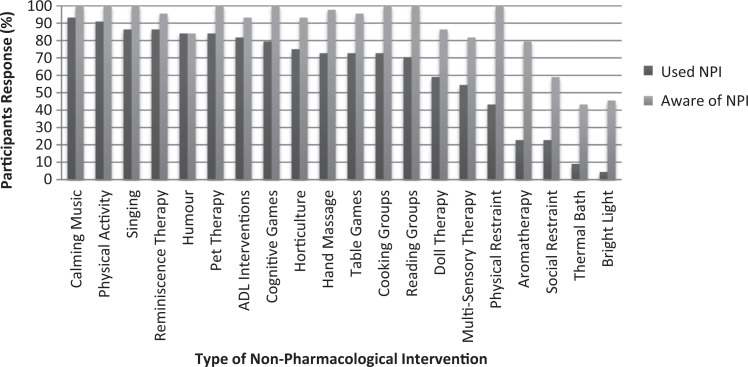

The NPIs questionnaire was a feasible and simple method of learning about both the current knowledge and the use of NPIs in the participating LTC facilities. The response rate of the questionnaire was 100%. Figure 1 shows the frequency of responses and the discrepancy between staff awareness about and use of NPIs. More than 80% of the staff was aware of the listed NPIs, with the exception of 3 NPIs (social restraint, thermal bath, and bright light therapy). Low-cost and easy-to-implement interventions, such as calming music, singing, and humor, were used most frequently, followed by organized recreational activities such as physical activity, horticulture, pet therapy, and reminiscence therapy. Of the respondents, 43% acknowledged that physical restraints were used in their facility, most frequently in the form of wheelchair seatbelts with the intent to improve the safety of the resident. Additionally, 6 NPIs, Montessori-based activities, art therapy, gentle persuasive techniques, redirection, distraction and scheduled quiet times, were added by the staff to the original list of NPIs.

Figure 1.

Summary of nonpharmacological interventions (NPIs) questionnaire results related to staff awareness and current utilization of NPIs in 5 participating long-term care facilities.

Compared with the results from the NPIs questionnaire, there was a notable difference in the types of NPIs that emerged from the focus groups and interviews. The 2 main NPIs discussed were reapproaching and distraction; these 2 interventions were used by all staff. Nurses and PSWs frequently mentioned these NPIs as they did not require additional resources and could be done simultaneously with the provision of one-to-one care. A manager with previous nursing background reiterated the importance of basic bedside care, “… calling them by name, inviting them to [do] things, being respectful, and treating them like they are part of the family, so you [staff] are not creating any agitation to begin with.” Scheduled activity programming was organized exclusively by the recreational therapists but was recognized as important by all participants. NPIs were used infrequently by 6 participants in management positions and 1 dietician due to the short time they spent on the units interacting directly with residents.

Participants reported that their awareness of NPIs stemmed mainly from at-work training, professional education, workplace experience, and self-initiated learning. At-work training sessions were the main educational resource; however, the participants in 3 focus groups described these sessions as too basic, repetitive, and not applicable. The recreation staff members found at-work sessions useful and were more engaged than other staff in further learning outside of work. Two participating facilities contracted a behavior analyst who provided information about NPIs and acted both as a support and as an educational resource for staff.

Agitation Management Using Medications

Pharmacological management was prevalent at all 5 facilities. Nurses and PSWs identified antipsychotics, antianxiety medications, and sedatives as the most commonly used medications to reduce agitation. Medications were administered both as scheduled and in as required (that is pro re nata [PRN]) form. Consensus among nurses and PSWs was that the urgency to moderate the agitated behavior dictated the response, and medications were used mainly when quick relief was necessary. Recreation staff and management did not support the use of PRNs as a first response but acknowledged that medications were necessary at times, especially when safety of residents or staff was compromised. An experienced RN stated that relying on medications to manage behaviors was a significant part of nursing culture in LTC. In her words “… we [nurses] are pro medicine, we are very medicine prone. Take a pill that makes it [agitation] better.” The PRN medications were perceived to be easy to administer, quick to reduce agitation, and effective for a longer period of time than NPIs. Because the majority of residents were receiving multiple medications upon admission to the LTC facility, a group of the nurses expressed skepticism that the concept of NPIs was even realistic. In the opinion of those nurses, NPIs could only be discussed as an addition to residents’ current medication regimen and PRN practices, and not considered in lieu of PRN medication options.

Medications to reduce agitation were given preventatively, for example before bathing routines, by staff at 2 participating facilities. One nurse described her patient during the bath as “… heavily medicated…” A portion of front line staff perceived the use of medications as necessary to keep the individual comfortable and to allow staff to complete their daily tasks in a timely manner. The PRN medications were also administered when the safety of the agitated resident, other residents, or staff was compromised, and this contextual-based administration was supported by all the participants. Nurses believed that they could accurately detect the cause of the agitation, and that NPIs were appropriate in situations when the need was emotional rather than physiological (eg, hunger, fatigue, or pain).

Participants acknowledged that the PRN medications for agitation, like all medications, could have potential side effects. A DOC elaborated “… as soon as you give someone medication to calm them down essentially they are at risk for other things, they’re in bed longer, they’re at risk for skin breakdown, they’re at risk for not eating well, and there’s dehydration. That is just a snowball effect.”

Agitation Management Using NPIs

Overall, the participants believed that successfully implemented NPIs can prevent and reduce agitation. The outcome of reduced agitation was perceived to be beneficial not only for the residents but also for the staff. The NPIs were perceived as effective in reducing agitation, because they focused the resident’s energy, gave the resident a sense of purpose, decreased the risk of unsafe behaviors, and improved mental stimulation and relaxation. The effectiveness of NPIs diminished if a resident was already in an escalated state of agitation, or when the resident posed harm to himself or herself and others. Despite nursing staff support for the use of PRN medications, consensus among participants was that the greatest benefit of NPIs was the reduced need for the use of PRN medications.

Although management and recreation therapy staff held stronger beliefs than nurses and PSWs about the effectiveness of NPIs, all participants felt NPIs were a strong solution for improving residents’ quality of life. A DOC stated “… the benefits are [related to] quality of life which is what you are looking for. The harms [of NPIs]? I don’t see any of them. I think any time you can be individually with a person, you are helping them.” Improving the lives of the residents and reducing agitation reaped benefits for the front line staff too, as a RPN explains, “… the more content your resident is, the better the staff are able to work with them; … they [residents] could be more compliant with what you [staff] need to do—bath them or dress them, or to have lunch.”

Facilitators and Barriers for NPI Implementation in LTC

The final objective of this study was to explore barriers and facilitators of NPI implementation. In total, 4 facilitators and 6 key barriers were identified.

The most frequently perceived facilitator for NPI use was familiarity with the resident. A recreation coordinator explains “… the more time you [staff] spend with them [residents], the more you figure out what works. So, consistency in staff and routine for them [residents] is [a] big [factor].” A positive relationship, trust, and familiarity between staff and residents were perceived to help staff select and implement the most appropriate NPI. Participants expressed that the familiarity of staff minimized the resident’s confusion and allowed them to focus on the NPI being implemented. Another identified facilitator was that any staff member could implement them with little training, whereas medications could only be administered by nursing staff. Each successful application of NPIs improved the staffs’ confidence in their ability to use NPIs effectively. Further, communication within the team and sharing successful strategies increased the likelihood that NPIs will subsequently be used by other staff. The selection of approach to deal with agitation was dependent on the degree of empathy exhibited by the staff. A highly empathetic unit manager understood that living in a complex LTC environment influenced adverse behavioral responses, “imagine leaving your own environment, coming into a place where it’s not familiar … living with other unfamiliar people… and having care done by people you don’t recognize.” Empathy of the staff appeared to coincide with openness to using NPIs.

Despite the facilitators listed previously, staff frequently did not use NPIs due to powerful barriers. The 2 major interconnected barriers were time constraints and low staff-to-resident ratios. The front line staff reported that they had heavy workloads and very little time to complete necessary tasks during their shift. An RN described the typical situation, “… at times there’s so little staff and there’s a lot of behaviors all at once. It’s just kind of putting out fires and keep things rolling…” The struggle with time was amplified by increased demands to complete documentation and engage in unscheduled jobs, such as the recreation staff’s involvement in feeding residents during mealtimes. Notably, participants from the privately owned LTC home felt that they did have adequate time to prevent and to manage agitation using NPIs, because they had a higher staff to resident ratio and the residents’ routine was more flexible (eg, unscheduled breakfast times). Thus, they were able to adapt their daily tasks to a pace and sequence that suited the resident’s mood and needs on any particular day.

Another barrier was a perception that NPI application was based on trial and error. Multiple factors (eg, time of day, personality of the staff or resident, and environment) made the outcome of the NPI use unpredictable. An added challenge for the selection of appropriate NPIs or programming was the diversity of residents. In the words of a recreation therapist “… now we have people in their 30s, 40s, 50s coming in [the facility] so programming for them … is very different than the programming for someone in their 80s.” Staff had to be acutely aware of the influences of dementia, confusion, delusions, and hallucinations that affected the person with respect to managing agitation. Staff reported that many NPIs had short-lasting effects, and the time invested in implementing a NPI was not balanced with the attained results. Cumulatively, these barriers minimized the appeal of NPIs as the primary method of agitation management in LTC facilities.

Discussion

This study confirmed that agitation was perceived to be prevalent in LTC facilities, and consequently, staff was faced with daily choices of how best to address agitation using PRN medications or using NPIs. The NPIs were often weighed against medications, which were viewed as a long-lasting and quicker solution for resolving acute agitation. Although the LTC staff possessed a high awareness of common NPIs, the use of NPIs was dependent on the staffs’ perceptions of the effectiveness, past success with the NPI use, and the number of other duties competing for staff’s time and attention. The 2 major perceived benefits of NPIs were the potential for implementation in both the prevention and the management of agitation, and that NPIs can be administered by every trained staff member regardless of their professional designation.

Some variation in perceptions between nursing, recreation and management staff was found, which was expected given the different professional roles and scope of practice. Agitation was interpreted differently based on the educational background of the staff member, and how they were trained to evaluate the situation and recognize the need. Medications were often viewed as a resource that allowed nurses and PSWs to reduce the agitation and complete daily care tasks successfully. Evidence shows that medications offer some therapeutic benefit to the agitated individual; however, the parameters of their use remain controversial and should be monitored closely and reevaluated frequently. 31,32 The side effects of medications, such as potential for increased agitation, 32 urinary tract infections, 31 or increased risk of mortality, 45 were not thoroughly discussed by nursing staff during the focus groups. Consensus was that both medications and NPIs had distinct roles in addressing agitation within LTC, and that NPIs were better suited to satisfy residents’ psychological needs such as the need for security, purpose, and human interaction.

Participants in this study reported lack of time, low staff-to-resident ratios, the unpredictable and short-lasting effects of NPIs, and physical environments as barriers to NPI implementation in daily practice. Weech-Maldonado et al 46 also reported lack of time, low staff-to-resident ratios, and the types of staff available as barriers in LTC that influenced the quality of care provided. Similarly, when Kaasalainen et al 47 asked LTC staff to review research protocols and report the potential barriers and facilitators to implementing the protocols, lack of time and available staff were the most dominant barriers noted. Nursing staff in this study felt that they were constantly “putting out fires” and stated that although they usually knew why the agitation was occurring, they did not have time to address the situation until the behavior escalated. At such a point, medications offered a more immediate and guaranteed result. Interestingly, resources (eg, supplies and equipment) for NPIs were not seen as a barrier at any of the participating facilities.

Although time and staffing levels are serious barriers for the NPI use, they represent systemic issues unlikely to be resolved in the near future. A more feasible and long-lasting solution to increasing the use of NPIs in LTC appears to be staff education. Better educating staff about the potential of NPIs, creating a work culture that supports the use of NPIs, and improving communication among staff could be the most effective strategies. The need for LTC staff education and training has been established, specifically addressing the interdisciplinary approach to recognizing, assessing, treating, and monitoring behavioral symptoms. 23

Participants in this study explained that education sessions they attended were repetitive, often uninformative, and typically provided in a lecture format. A critical review of the literature on the continuing education in LTC by Aylward et al 48 found that 35 of the 48 programs reviewed consisted of only predisposing factors (eg, communication or dissemination of information), while facilitating factors (eg, conditions enabling individual to implement new skills) and reinforcing factors (eg, reminders to use or enhance the use of new skills) were missing. The importance of combining all 3 types of factors was reiterated in a review by Kuske and colleagues 49 who reported that interventions combining all 3 show continuous knowledge transfer and positive behavioral changes in residents. To alter staff behavior, organizational and system changes within LTC must also occur. 49 The work environment needs to be altered to allow training time, to have clear protocols established, to enable staff to implement new knowledge, and to put in place the feedback and reminder mechanisms through which new knowledge will be reinforced. 48,49 It is apparent that effective and sustainable education in LTC extends beyond the individual staff members and requires organizational and societal (eg, Ministry of Health) support.

Educational sessions should also encourage open communication between staff and reliance on individualized care plans. Information describing the need the resident typically expresses through agitation and information about previously successful applications of a particular NPI with the resident should be included in the care plans and made available to all staff members. By properly evaluating and documenting the need and the intervention, the likelihood of successful NPI implementation for other staff may increase.

Participants reported that NPIs could be passively incorporated into daily activities and easily tailored to the individual. Examples included distraction tactics, redirection, humor, and singing. When staff worked in interdisciplinary teams, NPIs could be implemented on a larger scale and more frequently. One participating LTC facility found a solution in creating “quiet time” during a peak time of agitation in mid-afternoons. During this time, noise was minimized, residents were kept separated within the available space, and everyone was encouraged to relax. Staff at this facility reported that the implemented changes were successful in minimizing agitation.

In summary, NPIs can be performed by any staff member present, provided that staff receives proper training for assessing the behavior and determining the most appropriate NPI for that particular individual and situation. Recreational therapists, who are in charge of scheduling programmed activities in LTC, could be seen as leaders in prevention of agitation, while a “supportive team” of all staff should be included in agitation management. Establishing new procedures and creating a work environment that encourages NPIs implementation before relying on medication management should be strived for.

Limitations

As with most qualitative research, this cross-sectional study with a group of purposefully selected LTC staff members has limited generalizability. Considering that this study was conducted in 4 publically funded and only 1 privately funded LTC homes, comparison and in-depth analysis of the influence of funding levels was not possible. A small number of participants at the managerial level also prevented an analysis of differences between perception of front line staff and management. The study participants were recruited through a gatekeeper at each participating facility which could have possibly introduced selection bias. However, the researchers worked to minimize bias through thorough member checking, regular research team discussions, triangulation when establishing the coding list, and consensus building regarding emerging themes. In terms of the data collection protocol, the NPIs questionnaire was administered prior to the focus groups and interviews and could have possibly educated the participants about NPIs that they were previously unaware of.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to investigate the perceptions of LTC staff about the current use of NPIs in reducing agitation in seniors with dementia and to identify perceived facilitators and barriers that impact NPI implementation. Findings indicate that agitation is a prevalent and burdensome problem experienced daily by the staff in LTC and is commonly managed pharmacologically. The NPIs were perceived to have short-lasting effects, to be based on trial and error, and were unbalanced in terms of time invested versus the gained benefit. Although the staff were knowledgeable about and trained to deliver a number of NPIs, their heavy workloads, task-oriented work schedule, and low staff-to-resident ratios limited NPI delivery. Nonetheless, all staffs’ ability to use NPIs, staff familiarity with residents, good team communication, and empathy were promising facilitators for future implementation of NPIs. An innovative “supportive team” approach between management, PSWs, recreation, and nursing staff is proposed to create an environment of open communication, multidisciplinary collaboration, and accountability for agitation management that will result in the best possible care for LTC residents.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere thanks to the long-term care staff who participated in this study and the gatekeepers who helped organize the focus groups.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer report 2012: overcoming the stigma of dementia. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2012. Accessed September 12, 2012.

- 2. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's Dement. 2012;8(2);131–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitty E, Flores S. Assisted living nursing practices: the language of dementia: theories and interventions. Geriatr Nurs. 2007;28(5):283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. Staffing and care standards for long-term care homes. http://www.rnao.org/Storgage/37/3163_RNAO_submission_to_MOHLTC_--_Staffing_and_Care_Standards_in_LTC_-_Dec_12_20071.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2012.

- 5. Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS. A description of agitation in a nursing home. J Gerontol. 1989;44(3):M77–M84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen-Mansfield J, Deutsch L. Agitation: subtypes and their mechanisms. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 1996;1(4):325–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen-Mansfield J, Billig N. Agitated behaviors in the elderly. I. A conceptual review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(10):711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camp CJ, Cohen-Mansfield J, Capezuti EA. Mental health services in nursing homes: use of nonpharmacological interventions among nursing home residents with dementia. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(11):1397–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacological interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lord T, Garner E. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills. 1993;76(2):451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gerdner L. Effects of individualized versus classical “relaxation” music on the frequency of agitation in elderly persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(1):49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Remington R. Calming music and hand massage. Nurs Res. 2000;51(5):317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alessi C, Yoon E, Schnelle J, Al-Samarrai NR, Cruise PA. A randomised trial of a combined physical activity and environment intervention in nursing home residents: do sleep and agitation improve? J AM Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(7):784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buettner LL, Fitzsimmons S. AD-venture program: therapeutic biking for the treatment of depression in long-term care residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2002;17(2):121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jarrott SE, Gigliotti CM. Comparing responses to horticultural-based and traditional activities in dementia care programs. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(8):657–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suzuki M, Tatsumi A, Otsuka T, et al. Physical and psychological effects of 6-week tactile massage on elderly patients with severe dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(8):680–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baker R, Bell S, Baker E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of multi-sensory stimulation (MSS) for people with dementia. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40(1):81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Staal JA, Sacks A, Matheis R, et al. The effects of Snoezelen (multi-sensory behavior therapy) and psychiatric care on agitation, apathy, and activities of daily living in dementia patients on a short term geriatric psychiatric inpatient unit. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2007;37(4):357–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Churchill M, Safaoui J, McCabe BW, Braun MM. Using a therapy dog to alleviate the agitation and desocialization of people with Alzheimer’s disease. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1999;37(4):16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richeson NE. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on agitated behaviours and social interactions of older adults with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2003;18(6):353–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verkaik R, van Weert JC, Francke AL. The effects of psychosocial methods on depressed, aggressive and apathetic behaviors of people with dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hermann N, Gauthier S, Lysy PG. Clinical practice guidelines for severe Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(4):385–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. American Geriatrics Society, American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Consensus statement on improving the quality of mental health care in U.S. nursing homes: management of depression and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(9):1287–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beck CK, Vogelpohl TS, Rasin JH, et al. Effects of behavioural interventions on disruptive behaviour and affect in demented nursing home residents. Nurs Res. 2002;51(4):219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, Paton J, Lyketsos CG. Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):1996–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alzheimer Society. The impact of dementia on Canadian society. http://www.alzheimer.ca/docs/RisingTide/Rising%20Tide_Full%20Report_Eng_FINAL_Secured%20version.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2012.

- 27. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 2005;293(5):596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bell JS, Taipale HT, Soini H, Pitkala KH. Sedative load among long-term care facility residents with and without dementia: a cross-sectional study. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30(1):63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ballard C, Corbett A. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(9):729–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Corbett A, Smith J, Creese B, Ballard C. Treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2012;14(2):113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):191–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Talerico KA, Evans LK, Strumpf NE. Mental health correlates of aggression in nursing home residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2002;42(2):169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hogan DB, Bailey P, Carswell A, et al. Management of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(4):355–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lewis DL, Jewell D, Turpie I, Patterson C, McCoy B, Baxter J. Translating evidence into practice: the case of dementia guidelines in specialized geriatric services. Can J Aging. 2005;24(3):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Manen M. Research Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy . London, Ontario, Canada: State University of New York Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Laverty SM. Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: a comparison of historical and methodological considerations. IJQM. 2003;2(3):1–29. http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/2_3final/pdf/laverty.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Buettner L, Fitzsimmons S. Dementia Practice Guideline for Recreation Therapy: Treatment of Disturbing Behaviors. New York, NY: American Therapeutic Recreation Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. London, England: Sage Publications Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kong E. Agitation in dementia: concept clarification. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):526–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Algase DL, Beck C, Kolanowski A, et al. Need-driven dementia-compromised behaviour: an alternative view of disruptive behaviour. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1996;11(6):10–19. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koch T, Harrington A. Re-conceptualizing rigour: the case for reflexivity. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(4):882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Darke P, Shanks G, Broadbent M. Successfully completing case study research: combining rigour, relevance and pragmatism. Inform Syst J. 2002;8(4):273–289. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mayan MJ. Essentials of Qualitative Inquiry. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gill SS, Bronskill SE, Normand SL, et al. Antipsychotic drug use and mortality in older adults with dementia. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(11):775–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weech-Maldonado R, Meret-Hanke L, Neff MC, Mor V. Nurse staffing patterns and quality of care in nursing homes. Health Care Manage Rev. 2004;29(2):107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kaasalainen S, Williams J, Hadjustavropoulos T, et al. Creating bridges between researchers and long-term care homes to promote quality of life. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(12):1689–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aylward S, Stolee P, Keat N, Jagncox. Effectiveness of continuing education in long-term care: a literature review. Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kuske B, Hanns S, Luck T, Angermeyer MC, Behrens J, Riedell-Heller SG. Nursing home staff training in dementia care: a systematic review of evaluated programs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(5):818–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]