Abstract

Background:

The validity of neuropsychological tests for the differential diagnosis of degenerative dementias may depend on the clinical context. We constructed a series of logistic models taking into account this factor.

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed the demographic and neuropsychological data of 301 patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal degeneration (FTLD), or dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Nine models were constructed taking into account the diagnostic question (eg, AD vs DLB) and subpopulation (incident vs prevalent).

Results:

The AD versus DLB model for all patients, including memory recovery and phonological fluency, was highly accurate (area under the curve = 0.919, sensitivity = 90%, and specificity = 80%). The results were comparable in incident and prevalent cases. The FTLD versus AD and DLB versus FTLD models were both inaccurate.

Conclusion:

The models constructed from basic neuropsychological variables allowed an accurate differential diagnosis of AD versus DLB but not of FTLD versus AD or DLB.

Keywords: dementia, Alzheimer disease, Lewy body disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, diagnosis, differential, demography, neuropsychological tests, and logistic models

Introduction

The differential diagnosis of degenerative dementias is an increasingly important task in clinical practice. 1 -3 Accurate identification of the distinct disorders may have practical implications on both prognosis and management. 1 -3 The most promising tests are those based on structural, functional, and molecular brain imaging, 4 -6 and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, 7,8 but their widespread use may be limited due to technical and economical factors.

Neuropsychological tests are routine tools for the evaluation of patients with cognitive complaints. These tests may accurately distinguish normal individuals from patients with cognitive impairment (eg, 9 ). However, it is uncertain whether they are also useful for the differential diagnosis of degenerative dementias. In a recent review, Karantzoulis and Galvin concluded that although typical cases show characteristic neuropsychological patterns, there is substantial overlap between the different disorders. 10 However, several authors have obtained good results using basic tests or combinations thereof. 11 -23 Mathuranath et al developed a composite score from the Adenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination that was highly discriminating between Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and frontotemporal dementia. 11 Kramer et al identified 5 variables that correctly classified 89.2% of their cases, comprising 30 patients with AD, 21 with frontotemporal dementia, and 14 with semantic dementia. 14 Diehl et al constructed a logistic model with animal fluency and the Boston Naming Test, which correctly classified 90.5% of their patients with AD and frontotemporal dementia. 15 Marra et al showed that clusters of cognitive and behavioral disorders could correctly identify 84.5% of their cases, including 20 patients with AD, 22 patients with frontal dementia, and 11 patients with nonfluent aphasia. 17 A combination of the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) and selected items from a novel questionnaire accurately classified 97% of 35 patients with frontotemporal dementia, 46 patients with AD, and 36 normal individuals. 19 Taken together, these data suggest that neuropsychological tests may be useful for the differential diagnosis of degenerative dementias, but their validity may be much dependent on the clinical context.

In this study, we performed a retrospective analysis of the demographic and neuropsychological findings in 301 patients with clinically diagnosed AD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), or dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). From these data, we developed a series of logistic regression models with diagnostic aims. In order to facilitate their clinical application, we only included a series of neuropsychological variables that are easily collected in practice. Furthermore, instead of constructing an all-purpose tool, we estimated different models taking into account the specific clinical question (AD vs FTLD, AD vs DLB, and FTLD vs DLB) and patient subpopulation (incident vs prevalent cases).

Methods

For the purpose of this study, we retrospectively analyzed 301 patients with degenerative dementias attended at the General Neurology Unit of the Hospital Ruber Internacional between January 1998 and January 2009. We included all patients with probable AD, FTLD, or DLB and formal neuropsychological testing. For the sake of consistency, we applied the diagnostic criteria available in 1998. 21 -23 The data were extracted from the clinical records. We registered the demographic and neuropsychological variables at the first visit and the final clinical diagnosis. The study followed the ethical requirements of our institution and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

We collected the following demographic data: age, sex, and level of education (categorized into 4 groups: none to preprimary level, primary level, secondary level, and bachelor to higher levels). Cases were also divided into 2 categories: incident (newly diagnosed) or prevalent (previously diagnosed).

The neuropsychological tests registered for analysis were the Miniexamen Cognoscitivo (MEC, an Spanish version of the Mini-Mental State Examination which scores over 35), 24 the selective reminding test and the clock test included in the 7 Minute screening battery, 25 the categorical (animals) and phonological fluency (letter p) tests, 26 the Trail Making Test (TMT) parts A and B, 27 the Geriatric Depression Scale with 15 items (GDS-15), 28 the Shortened Spanish-Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (SS-IQCODE), 29 and the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ). 30 The selective reminding test was coded into 4 variables: naming, free recall, facilitated recall, and memory recovery. Memory recovery was calculated as facilitated recall/(16 − free recall), where 16 is the total number of items in the reminding test. Results of TMT were categorized into 7 groups according to percentiles.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 19 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, New York) and R 2.10.1 software. 31 We constructed a series of logistic regression models taking the clinical diagnosis as the dependent variable (AD, FTLD, or DLB), and the demographic and neuropsychological data as the independent variables. The models were selected with a back step elimination method according to the likelihood ratio test and applying the standard P values for variable inclusion (.05) and exclusion (.1). We used an automated selection method because our aim was predictive and not explicative. Since the size of the smallest group was limited (37 patients with DLB), we only included in the initial models those variables with P <.2 in the bivariable tests (Kruskall-Wallis and Wilcoxon tests for ordinal and quantitative data and Pearson’s chi-square test for nominal data). The individual significance of the variables was estimated according to their odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Goodness of fit was evaluated with the Nagelkerke R 2 coefficient and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Internal validity was analyzed according to the area under the receiver–operator characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), the sensitivity, and the specificity. The optimal cutoff points were selected from the ROC curves. Among all possible values, we chose those that best equilibrated the sensitivity and specificity of the models around 80% or above. The sensitivity and specificity of the models for incident and prevalent cases were compared with the Pearson’s chi-square test.

Results

We identified 301 patients with clinically diagnosed degenerative dementias, including 199 (66.1%) patients with AD, 65 (21.6%) patients with FTLD, and 37 patients (12.3%) with DLB. The FTLD cases comprised 38 (58.5%) patients with the behavioral variant, 6 (9.2%) patients with progressive nonfluent aphasia, 3 (4.6%) patients with semantic dementia, and 18 (27.7%) patients with mixed manifestations. Therefore, our patients with FTLD were mainly representative of the (frontal) behavioral variant (fv-FTLD). There were 181 incident cases, including 122 (67.4%) patients with AD, 42 (23.2%) patients with FTLD, and 17 (9.4%) patients with DLB, and 120 prevalent cases, including 77 (64.2%) patients with AD, 23 (19.2%) patients with FTLD, and 20 (16.7%) patients with DLB. The demographic and neuropsychological data of the 3 groups, and the significance of the overall (3 groups) bivariable tests, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Neuropsychological Findings in 301 Patients With Clinically Diagnosed Alzheimer’s Disease, Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration, or Dementia With Lewy Bodies.a

| Alzheimer’s Disease (n = 199) | Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (n = 65) | Dementia With Lewy bodies (n = 37) | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 77.2 (7.6) | 72.1 (10.3) | 75.4 (6.1) | <.001 |

| 77.6 (48.5-100) | 73.6 (36.6-100) | 75.8 (60.4-86.7) | ||

| Female sex, frequency (%) | 119/199 (59.8) | 30/65 (46.2) | 11/37 (29.7) | .002 |

| Level of education | 1.7 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.1) | .017 |

| 1 (0-3) | 3 (0-3) | 1 (0-3) | ||

| MEC | 25.1 (6.3) | 27.0 (6.3) | 25.4 (6.8) | .033 |

| 26 (0-35) | 29 (3-35) | 26 (0-35) | ||

| Naming | 12.4 (4.1) | 12.0 (5.0) | 13.3 (3.2) | .377 |

| 14 (0-16) | 15 (0-16) | 15 (6-16) | ||

| Free recall | 2.7 (2.2) | 4.0 (2.7) | 3.6 (2.3) | <.001 |

| 2 (0-9) | 4 (0-11) | 3.5 (0-11) | ||

| Facilitated recall | 5.3 (3.3) | 6.5 (3.5) | 7.0 (3.1) | .001 |

| 5 (0-13) | 7 (0-14) | 7.5 (0-11) | ||

| Memory recovery | 0.435 (0.298) | 0.595 (0.329) | 0.595 (0.274) | <.001 |

| 0.408 (0-1) | 0.667 (0-1) | 0.626 (0-1) | ||

| Categorical fluency | 9.4 (5.0) | 9.2 (5.1) | 9.4 (5.0) | .966 |

| 9 (0-25) | 8 (1-20) | 8.5 (3-24) | ||

| Phonological fluency | 7.1 (4.6) | 6.4 (4.7) | 3.3 (3.0) | .039 |

| 7 (0-20) | 5 (0-18) | 3 (0-11) | ||

| TMT part A | 2.4 (1.9) | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.9 (4.0) | .006 |

| 2.5 (0-6) | 3 (0-6) | 1 (0-6) | ||

| TMT part B | 1.2 (1.9) | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.5 (1.2) | .468 |

| 0 (0-6) | 0 (0-5) | 0 (0-5) | ||

| Clock test | 3.5 (2.6) | 4.0 (2.5) | 2.0 (2.5) | .008 |

| 3 (0-7) | 4 (0-7) | 1 (0-7) | ||

| SS-IQCODE | 69.3 (12.8) | 67.5 (9.7) | 65.8 /16.8) | .003 |

| 71 (4-98) | 67.5 (43-105) | 69 (0-81) | ||

| FAQ | 16.0 (12.6) | 12.9 (9.1) | 17.2 (10.7) | .232 |

| 13.5 (0-78) | 13 (0-30) | 19.5 (2-31) | ||

| GDS-15 | 5.7 (2.7) | 5.2 (2.6) | 4.6 (4.8) | .203 |

| 5 (0-13) | 5.5 (1-11) | 2.5 (0-14) |

Abbreviations: MEC, Miniexamen Cognoscitivo; TMT, Trail Making Test; SS-IQCODE, Shortened Spanish-Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; FAQ, Functional Assessment Questionnaire; GDS-15, Geriatric Depression Scale with 15 items.

a The results are shown as mean (standard deviation) in the first line and median (range) in the second line, except for female sex.

b Overall comparisons of the 3 groups with the Kruskall-Wallis test for ordinal and quantitative data, and the Pearson chi-square test for nominal data.

Dementia with Lewy body versus AD (2 groups) bivariable tests showed significant differences in sex (P = .001), phonological fluency (P < .001), clock test (P = .003), free recall (P = .035), facilitated recall (P = .008), and memory recovery (P = .005). The FTLD versus AD tests showed significant differences in age (P < .001), level of education (P = .005), MEC (P = .016), free recall (P < .001), facilitated recall (P = .024), memory recovery (P = .001), and SS-IQCODE (P = .03). The DLB versus FTLD tests showed significant differences in age (P = .035), phonological fluency (P < .001), and clock test (P < .001).

The logits and goodness-of-fit parameters of the 9 multivariable logistic regression models are shown in Table 2. The model for the differential diagnosis between DLB and AD constructed from all cases was composed of memory recovery (OR = 1.73; 95% CI = 1.4-2.1) and phonological fluency (OR = 0.491; 95% CI = 0.375-0.642). The OR values for memory recovery reflect an increase in 0.1 points. The model for incident cases was also composed of memory recovery (OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.2-2.1) and phonological fluency (OR = 0.510; 95% CI = 0.355-0.732). The corresponding values for prevalent cases were memory recovery (OR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.4-2.8) and phonological fluency (OR = 0.472; 95% CI = 0.309-0.720).

Table 2.

Logits, Nagelkerke R 2 Coefficients, and Hosmer-Lemeshow (H-L) P Values of 9 Logistic Regression Models for the Differential Diagnosis Between Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (FTLD), and Dementia With Lewy Bodies (DLB).

| DLB vs AD | ||

| All cases | Logit | −1.636 + (5.482 × recovery) − (0.712 × Ph. fluency) |

| R 2 | 0.510 | |

| H-L | .938 | |

| Incident cases | Logit | −1.431 + (4.465 × recovery) − (0.672 × Ph. fluency) |

| R 2 | 0.450 | |

| H-L | .913 | |

| Prevalent cases | Logit | −1.895 + (6.885 × recovery) − (0.751 × Ph. fluency) |

| R 2 | 0.585 | |

| H-L | .992 | |

| FTLD vs AD | ||

| All cases | Logit | 2.762 − (0.075 × age) + (0.345 × level of education) + (0.165 × facilitated recall) |

| R 2 | 0.185 | |

| H-L | .390 | |

| Incident cases | Logit | 4.568 − (0.080 × age) + (0.074 × facilitated recall) |

| R 2 | 0.103 | |

| H-L | .029 | |

| Prevalent cases | Logit | 2.271 − (0.062 × age) + (0.183 × facilitated recall) |

| R 2 | 0.147 | |

| H-L | .038 | |

| DLB vs FTLD | ||

| All cases | Logit | 0.413 − (0.204 × Ph. fluency) |

| R 2 | 0.169 | |

| p H-L | .846 | |

| Incident cases | Logit | −2.555 + (0.023 × age) − (0.028 × facilitated recall) |

| R 2 | 0.022 | |

| H-L | .436 | |

| Prevalent cases | Logit | −6.565 + (0.080 × age) + (0.092 × facilitated recall) |

| R 2 | 0.134 | |

| H-L | .456 | |

Abbreviation: Ph. fluency, Phonological fluency.

The model for the differential diagnosis between FTLD and AD constructed from all cases included 3 variables: age (OR = 0.928; 95% CI = 0.890-0.967), level of education (OR = 1.412; 95% CI = 1.007-1.981), and facilitated recall (OR = 1.180; 95% CI = 1.057-1.316). The model for incident cases was composed of 2 variables: age (OR = 0.923; 95% CI = 0.874-0.975) and facilitated recall (OR = 1.081; 95% CI = 0.953-1.227). The model for prevalent cases also included age (OR = 0.940; 95% CI = 0.886-0.997) and facilitated recall (OR = 1.200; 95% CI = 1.027-1.403).

The model for the differential diagnosis between DLB and FTLD constructed from all cases was composed only of phonological fluency (OR = 0.815; 95% CI = 0.717-0.926). The model for incident cases included age (OR = 1.024; 95% CI = 0.956-1.096) and facilitated recall (OR = 0.973; 95% CI = 0.796-1.189). The model for prevalent cases included the same variables: age (OR = 1.083; 95% CI = 0.983-1.194) and facilitated recall (OR = 1.096; 95% CI = 0.913-1.316).

Since memory recovery is obtained from free and facilitated recall, the initial steps of logistic regression could be interfered by multicollinearity. Therefore, we also calculated the AUC of the models composed of free and facilitated recall instead of memory recovery (DLB vs AD) and memory recovery instead of facilitated recall (FTLD vs AD). None of these models improved the previous results.

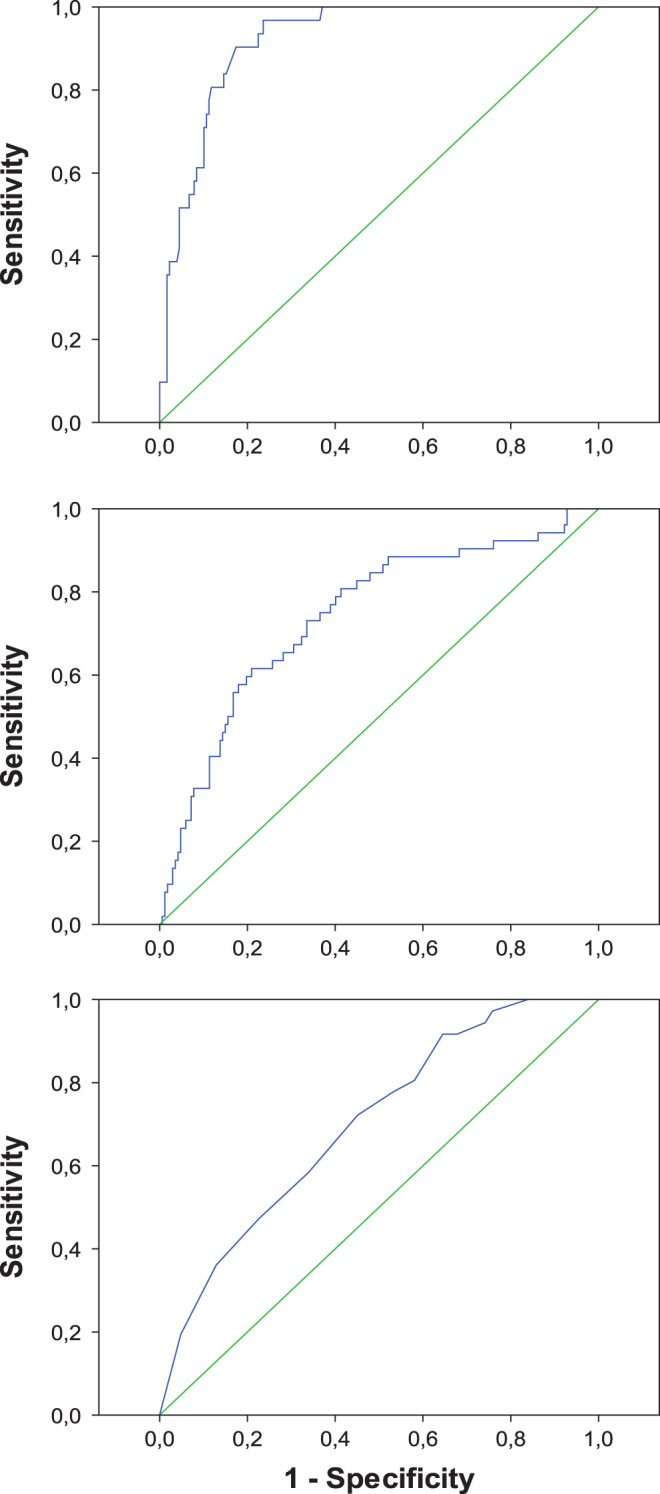

The parameters of internal validity of the multivariable models are shown in Table 3, and the ROC curves of the 3 models constructed from all patients are depicted in Figure 1. The cutoff values for estimation of sensitivity and specificity were 0.150 for the 3 DLB versus AD models, 0.200 for the 3 FTLD versus AD models, and 0.450, 0.250, and 0.500 for the DLB versus FTLD models obtained from all patients, incident cases, and prevalent cases, respectively. The comparison of the validity of the models for incident and prevalent cases did not show statistically significant differences, except for the specificity of FTLD versus AD: (1) DLB vs AD: sensitivity: chi-square = 0.754, P = .385 and specificity: chi-square = 0.022, P = .883; (2) FTLD vs AD: sensitivity: chi-square = 0.010, P = .921 and specificity: chi-square = 7.446, P = .006; and (3) DLB vs FTLD: sensitivity: chi-square = 2.358, P = .125 and specificity: chi-square = 3.728 P = .054.

Table 3.

Parameters of Internal Validity of 9 Logistic Regression Models for the Differential Diagnosis Between Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (FTLD), and Dementia With Lewy Bodies (DLB).

| AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DLB vs AD | |||

| All cases | 0.919 (0.880-0.959) | 90.3% (75.1%-97.0%) | 82.0% (75.7%-87.0%) |

| Incident cases | 0.908 (0.848-0.968) | 92.9% (68.5%-98.7%) | 81.9% (73.5%-88.1%) |

| Prevalent cases | 0.929 (0.875-0.984) | 82.4% (59.0%-93.8%) | 83.1% (72.7%-90.0%) |

| FTLD vs AD | |||

| All cases | 0.742 (0.663-0.821) | 75.0% (61.8%-84.8%) | 61.1% (53.5%-68.1%) |

| Incident cases | 0.693 (0.580-0.805) | 81.1% (65.8%-90.5%) | 38.1% (29.4%-47.6%) |

| Prevalent cases | 0.704 (0.562-0.845) | 80.0% (58.4%-91.9%) | 59.2% (47.5%-69.8%) |

| DLB vs FTLD | |||

| All cases | 0.701 (0.597-0.805) | 58.3% (42.2%-72.9%) | 66.1% (53.7%-76.7%) |

| Incident cases | 0.624 (0.470-0.777) | 85.7% (60.1%-96.0%) | 43.2% (28.7%-59.1%) |

| Prevalent cases | 0.661 (0.487-0.835) | 61.1% (38.6%-79.7%) | 70.0% (48.1%-85.5%) |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Receiver–operator characteristic curves of 3 logistic regression models for the differential diagnosis between dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease (upper panel), frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease (middle panel), and dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (lower panel).

Discussion

The validity of neuropsychological tests for the differential diagnosis of degenerative dementias is still uncertain. On one hand, there is ample evidence on the existence of typical neuropsychological patterns in the distinct disorders. 10,14,32 On the other hand, there is substantial overlap in the distribution of neuropsychological variables in the different groups, which may limit their diagnostic accuracy in particular clinical contexts. 10,33 With this point in mind, we constructed a series of multivariable logistic regression models taking into account the specific clinical question (eg, DLB vs AD) and patient subpopulation (incident vs prevalent cases).

The resulting model for the differential diagnosis of DLB and AD obtained from all cases was highly accurate: AUC = 0.919, sensitivity = 90.3%, and specificity = 80.2%. These results were comparable to those obtained separately for incident and prevalent cases. The 3 models were composed of memory recovery and phonological fluency. Levy and Chelune concluded that DLB and Parkinson’s disease with dementia are contrasted with AD by defective processing of visual information, better performance on executively supported verbal learning tasks, greater attentional variability, poorer qualitative executive functioning, and the presence of mood-congruent visual hallucinations. 32 In our series, patients with AD had the lowest scores in free recall, facilitated recall, and memory recovery. This pattern of memory impairment is typical of AD from its early stages. 34 In contrast, patients with DLB had the lowest scores in phonological fluency and clock drawing test, accounting for the executive and visuospatial deficits observed in this disorder. 35 In agreement with our data, other authors have shown that memory deficits are more severe in AD than in DLB, 36 and executive and visuospatial deficits are more severe in DLB than in AD. 35 Concerning demographic variables, Kraybill et al did not find significant differences between AD and DLB. 37 In our series, the AD group included a higher proportion of females than the DLB group (59.8% vs 29.7%; P = .001). Using a different approach, other authors have analyzed particular cognitive or behavioral functions, such as qualitative performance, 38 personality traits, 39 pentagon drawing, 40,41 clock drawing, 42 the Bender Gestalt Test, 43 and action fluency tasks. 44 In contrast to a previous report, 45 we did not find significant differences in GDS scores between patients with AD and DLB.

In comparison to the DLB versus AD models, the multivariable models for the differential diagnosis of FTLD versus AD and FTLD versus DLB showed low accuracy. Although their corresponding AUC values were moderate, most of the sensitivity and specificity values were under 80%. These results suggest that the behavioral and executive changes characteristic of our patients with FTLD, mainly fv-FTLD, were not adequately addressed by our battery of neuropsychological tests. This test battery may be representative of those used in primary care or general neurology settings 1 -3 but not in specialized memory clinics.

With regard to the differential diagnosis of AD and FTLD, a previous meta-analysis of 94 studies, comprising 2936 patients with AD and 1748 patients with FTLD, showed that the most discriminating cognitive tests were measures of orientation, memory, language, visuomotor function, and general cognitive ability. 33 Although there were large and significant differences between groups on these measures, there was substantial overlap in the scores of the AD and FTLD groups, even for executive functions. 33,46 In this line, our patients with FTLD did not show a particular pattern of impairment compared to the patients with AD. This result might be explained by the mixture of patients with FTLD having different lesional distribution 47 and the major behavioral problems of these patients. In spite of the apparent overlap, several authors have obtained good results with multivariable models constructed from simple tests, such as a logistic model combining phonemic fluency, Rey-Osterreith complex figure recall, oral apraxia, and cube analysis 12 ; a logistic model composed of social conduct disorders, hyperorality, akinesia, absence of amnesia, and absence of perceptual disorders 13 ; a discriminant function derived from a brief neuropsychological battery 14 ; a logistic model comprising animal fluency and the Boston Naming Test 15 ; a model derived from the Frontal Behavioural Inventory, the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, and the TMT part B 16 ; a discriminant function based on 3 factors (amnesic, behavioral, and linguistic) 17 ; a logistic model derived from the Philadelphia Brief Assessment of Cognition 18 ; a linear discriminant function combining the FAB with selected items from a novel behavioral and cognitive questionnaire 19 ; and a model combining 3 executive tasks (Hayling Test of Inhibitory Control, Digit Span Backward, and Letter Fluency). 20 Other authors have instead analyzed the performance of patients with AD and FTLD in single tests or scales, which makes it difficult to compare their data to our findings. 48 -66 Of note, the accuracy of the FAB for the differential diagnosis of AD and FTLD has been shown to be moderate 67 to low, 68,69 but some FAB subscores could still be useful. 70 The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination seems to be more promising to this end. 11,71

Concerning the differential diagnosis of DLB and FTLD, there is a paucity of information on direct comparisons of their neuropsychological features. In our series, patients with DLB were older and obtained lower scores in the clock drawing test and the phonological fluency test than those with FTLD. Engelborghs et al reported that patients with FTLD had a high prevalence (70%) of apathy, whereas delusions and hallucinations were rare. 72 In contrast, patients with DLB showed a high prevalence of disinhibition (65%) and frontal lobe involvement according to the Middelheim Frontality Score. Piguet et al studied the frequency of FTLD and DLB in a cohort of 170 patients with probable or possible AD. They concluded that the presence of core clinical features of non-AD dementia syndromes is common in AD and that the concordance between clinical and pathological diagnoses of dementia was variable, reflecting the need for further improvement in current diagnostic criteria. 73 Other authors have described an interesting case series of 6 patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of both FTLD and DLB. 74 Histologic examination of 2 of them was consistent with a Transactive Response DNA Binding Protein 43 KDa (TDP-43) proteinopathy, showing again the difficulty in predicting the pathological substrates from the clinical manifestations.

Additionally, we identified some interesting data when the models for the differential diagnosis of FTLD versus AD or DLB were evaluated. First, age at first examination and facilitated recall remained in most of the final models, which suggests that they could be valuable components of future multivariable models. The inclusion of age in these models most likely reflects the younger age of patients with FTLD in comparison to patients with AD and DLB. 23 Second, the patients with FTLD had a higher level of education than those with AD even after controlling for other demographic and neuropsychological variables, which suggests a differential effect of cognitive reserve on both disorders (see also 33 ).

The main limitation of our study is the lack of pathological confirmation. In order to increase the accuracy of clinical diagnosis, we considered the last available diagnosis in medical records. This way we took into account a consistent clinical progress. A second limitation is the retrospective nature of data collection. However, we registered the first neuropsychological evaluation, conducted before reaching the final diagnosis, which provides a forward sense to subsequent data analysis. A third potential problem is the possibility of incorporation bias that may lead to a kind of circular argument. The risk of this bias is especially high for AD, which is clinically defined by its neuropsychological features. In contrast, DLB and fv-FTLD are mainly identified on the basis of noncognitive manifestations, such as visual hallucinations and parkinsonism in the former and behavioral changes in the latter. Therefore, in strict sense, our results show the value of the demographic and neuropsychological variables in predicting the clinical diagnoses and not the pathologically defined disorders. A fourth conflicting point is the analysis of the patients with FTLD. In spite of the existence of obvious clinical subtypes, we decided to merge all our cases, as we were most interested in detecting group differences between the main degenerative disorders. However, this approach might reduce the ability of the models to differentiate FTLD from atypical presentations of AD and DLB, such as the logopenic variant of AD. In any case, since most of our patients with FTLD corresponded to the behavioral variant, our results mainly apply to this particular subtype. Finally, we also noticed a low prevalence of DLB cases in our study population. This finding might be caused by the fact that these patients were primarily evaluated in the movement disorders unit of our institution, and it suggests that the patients with DLB who were finally analyzed were those with prominent cognitive or behavioral manifestations and mild motor symptoms.

From the previous data, we can draw 2 suggestions for clinical practice. First, the differential diagnosis of AD and DLB may be significantly aided by the evaluation of simple neuropsychological variables, such as memory recovery and phonological fluency. Second, the differential diagnosis of fv-FTLD from AD and DLB most likely needs the application of behavioral scales and/or executive tests other than the TMT or the FAB.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PC was supported by a Ramon y Cajal Fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (RYC-2010-05748).

References

- 1. Maalouf M, Ringman JM, Shi J. An update on the diagnosis and management of dementing conditions. Rev Neurol Dis. 2011;8 (3-4):e68–e87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Geldmacher DS, Kerwin DR. Practical diagnosis and management of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease in the primary care setting: an evidence-based approach. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4):PCC.12r01474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Galasko D. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with dementia. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2013;19 (2 Dementia):397–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hinds SR II, Stocker DJ, Bradley YC. Role of positron emission tomography/computed tomography in dementia. Radiol Clin North Am. 2013;51 (5):927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jacobs HI, Radua J, Luckmann HC, Sack AT. Meta-analysis of functional network alterations in Alzheimer's disease: toward a network biomarker. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37 (5):753–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mortimer AM, Likeman M, Lewis TT. Neuroimaging in dementia: a practical guide. Pract Neurol. 2013;13 (2):92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blennow K, Zetterberg H. The application of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in early diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97 (3):369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Engelborghs S, Le Bastard N. The impact of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers on the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Diagn Ther. 2012;16 (3):135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer's disease centers' uniform data set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23 (2):91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karantzoulis S, Galvin JE. Distinguishing Alzheimer's disease from other major forms of dementia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11 (11):1579–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mathuranath PS, Nestor PJ, Berrios GE, Rakowicz W, Hodges JR. A brief cognitive test battery to differentiate Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2000;55(11):1613–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siri S, Benaglio I, Frigerio A, Binetti G, Cappa SF. A brief neuropsychological assessment for the differential diagnosis between frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8 (2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosen HJ, Hartikainen KM, Jagust W, et al. Utility of clinical criteria in differentiating frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) from AD. Neurology. 2002;58 (11):1608–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kramer JH, Jurik J, Sha SJ, et al. Distinctive neuropsychological patterns in frontotemporal dementia, semantic dementia, and Alzheimer disease. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2003;16 (4):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diehl J, Monsch AU, Aebi C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia, semantic dementia, and Alzheimer's disease: The contribution of standard neuropsychological tests to differential diagnosis. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18 (1):39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heidler-Gary J, Gottesman R, Newhart M, Chang S, Ken L, Hillis AE. Utility of behavioral versus cognitive measures in differentiating between subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23 (3):184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marra C, Quaranta D, Zinno M, et al. Clusters of cognitive and behavioral disorders clearly distinguish primary progressive aphasia from frontal lobe dementia, and Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24 (5):317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Libon DJ, Massimo L, Moore P, et al. Screening for frontotemporal dementias and Alzheimer's disease with the Philadelphia brief assessment of cognition: a preliminary analysis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24 (6):441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Valverde AH, Jimenez-Escrig A, Gobernado J, Baron M. A short neuropsychologic and cognitive evaluation of frontotemporal dementia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111 (3):251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hornberger M, Savage S, Hsieh S, Mioshi E, Piguet O, Hodges JR. Orbitofrontal dysfunction discriminates behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30 (6):547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1984;34 (7):939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): Report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47 (5):1113–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51 (6):1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lobo A, Ezquerra J, Gomez Burgada F, Sala JM, Seva Diaz A. El miniexamen cognoscitivo (un “test” sencillo, práctico, para detectar alteraciones intelectuales en pacientes médicos). Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines. 1979;7 (3):189–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. del Ser T, Sanchez-Sanchez F, Garcia de Yebenes MJ, Otero A, Munoz DG. Validation of the seven-minute screen neurocognitive battery for the diagnosis of dementia in a Spanish population-based sample. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22 (5-6):454–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Butman J, Allegri RF, Harris P, Drake M. Fluencia verbal en español. Datos normativos en Argentina. Medicina (B Aires). 2000;60 (5 pt 1):561–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tombaugh TN. Trail making test A and B: Normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19 (2):203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martinez de la Iglesia J, Onis Vilches MC, Duenas Herrero R, Aguado Taberne C, Albert Colomer C, Arias Blanco MC. Abreviar lo breve. Aproximación a versiones ultracortas del cuestionario de Yesavage para el cribado de la depresión. Aten Primaria. 2005;35 (1):14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morales JM, Gonzalez-Montalvo JI, Bermejo F, Del-Ser T. The screening of mild dementia with a shortened Spanish version of the “informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly”. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995;9 (2):105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37 (3):323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing ed. Vienna, Austria: http://www.R-project.org.; 2009.

- 32. Levy JA, Chelune GJ. Cognitive-behavioral profiles of neurodegenerative dementias: Beyond Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007;20 (4):227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hutchinson AD, Mathias JL. Neuropsychological deficits in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: A meta-analytic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78 (9):917–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Welsh K, Butters N, Hughes J, Mohs R, Heyman A. Detection of abnormal memory decline in mild cases of Alzheimer's disease using CERAD neuropsychological measures. Arch Neurol. 1991;48 (3):278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Collerton D, Burn D, McKeith I, O'Brien J. Systematic review and meta-analysis show that dementia with Lewy bodies is a visual-perceptual and attentional-executive dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16 (4):229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Simard M, van Reekum R, Myran D, et al. Differential memory impairment in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Cogn. 2002;49 (2):244–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kraybill ML, Larson EB, Tsuang DW, et al. Cognitive differences in dementia patients with autopsy-verified AD, Lewy body pathology, or both. Neurology. 2005;64 (12):2069–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Doubleday EK, Snowden JS, Varma AR, Neary D. Qualitative performance characteristics differentiate dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72 (5):602–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Galvin JE, Malcom H, Johnson D, Morris JC. Personality traits distinguishing dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;68 (22):1895–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cormack F, Aarsland D, Ballard C, Tovee MJ. Pentagon drawing and neuropsychological performance in dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19 (4):371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Caffarra P, Gardini S, Dieci F, et al. The qualitative scoring MMSE pentagon test (QSPT): A new method for differentiating dementia with Lewy body from Alzheimer's disease. Behav Neurol. 2013;27 (2):213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cahn-Weiner DA, Williams K, Grace J, Tremont G, Westervelt H, Stern RA. Discrimination of dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease using the clock drawing test. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2003;16 (2):85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murayama N, Iseki E, Yamamoto R, Kimura M, Eto K, Arai H. Utility of the Bender gestalt test for differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer's disease in patients showing mild to moderate dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23 (4):258–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Delbeuck X, Debachy B, Pasquier F, Moroni C. Action and noun fluency testing to distinguish between Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35 (3):259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yamane Y, Sakai K, Maeda K. Dementia with Lewy bodies is associated with higher scores on the geriatric depression scale than is Alzheimer's disease. Psychogeriatrics. 2011;11 (3):157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giovagnoli AR, Erbetta A, Reati F, Bugiani O. Differential neuropsychological patterns of frontal variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease in a study of diagnostic concordance. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46 (5):1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kipps CM, Knibb JA, Patterson K, Hodges JR. Neuropsychology of frontotemporal dementia. In: Goldenberg G, Miller BL, eds. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol 88. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2008:528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Swartz JR, Miller BL, Lesser IM, et al. Behavioral phenomenology in Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia, and late-life depression: a retrospective analysis. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1997;10 (2):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mendez MF, Doss RC, Cherrier MM. Use of the cognitive estimations test to discriminate frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1998;11 (1):2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mendez MF, Perryman KM, Miller BL, Cummings JL. Behavioral differences between frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: A comparison on the BEHAVE-AD rating scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1998;10 (2):155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Varma AR, Snowden JS, Lloyd JJ, Talbot PR, Mann DM, Neary D. Evaluation of the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria in the differentiation of Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66 (2):184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bozeat S, Gregory CA, Ralph MA, Hodges JR. Which neuropsychiatric and behavioural features distinguish frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69 (2):178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bathgate D, Snowden JS, Varma A, Blackshaw A, Neary D. Behaviour in frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103 (6):367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pasquier F, Grymonprez L, Lebert F, Van der Linden M. Memory impairment differs in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Neurocase. 2001;7 (2):161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grossi D, Fragassi NA, Chiacchio L, et al. Do visuospatial and constructional disturbances differentiate frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease? An experimental study of a clinical belief. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17 (7):641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nedjam Z, Devouche E, Dalla Barba G. Confabulation, but not executive dysfunction discriminate AD from frontotemporal dementia. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11 (11):728–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Thompson JC, Stopford CL, Snowden JS, Neary D. Qualitative neuropsychological performance characteristics in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76 (7):920–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. De Deyn PP, Engelborghs S, Saerens J, et al. The Middelheim frontality score: a behavioural assessment scale that discriminates frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20 (1):70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mendez MF, Licht EA, Shapira JS. Changes in dietary or eating behavior in frontotemporal dementia versus Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23 (3):280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Milan G, Lamenza F, Iavarone A, et al. Frontal behavioural inventory in the differential diagnosis of dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;117 (4):260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Salmon E, Perani D, Collette F, et al. A comparison of unawareness in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79 (2):176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Torralva T, Roca M, Gleichgerrcht E, Lopez P, Manes F. INECO frontal screening (IFS): A brief, sensitive, and specific tool to assess executive functions in dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15 (5):777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bird CM, Chan D, Hartley T, Pijnenburg YA, Rossor MN, Burgess N. Topographical short-term memory differentiates Alzheimer's disease from frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hippocampus. 2010;20 (10):1154–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gustafson L, Englund E, Brunnstrom H, et al. The accuracy of short clinical rating scales in neuropathologically diagnosed dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18 (9):810–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Franceschi M, Caffarra P, Savare R, Cerutti R, Grossi E, Tol Research Group. Tower of London test: a comparison between conventional statistic approach and modelling based on artificial neural network in differentiating fronto-temporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. Behav Neurol. 2011;24 (2):149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bellassen V, Igloi K, de Souza LC, Dubois B, Rondi-Reig L. Temporal order memory assessed during spatiotemporal navigation as a behavioral cognitive marker for differential Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. J Neurosci. 2012;32 (6):1942–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Slachevsky A, Villalpando JM, Sarazin M, Hahn-Barma V, Pillon B, Dubois B. Frontal assessment battery and differential diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2004;61 (7):1104–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Castiglioni S, Pelati O, Zuffi M, et al. The frontal assessment battery does not differentiate frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22 (2):125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Boban M, Malojcic B, Mimica N, Vukovic S, Zrilic I. The frontal assessment battery in the differential diagnosis of dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25 (4):201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lipton AM, Ohman KA, Womack KB, Hynan LS, Ninman ET, Lacritz LH. Subscores of the FAB differentiate frontotemporal lobar degeneration from AD. Neurology. 2005;65 (5):726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yew B, Alladi S, Shailaja M, Hodges JR, Hornberger M. Lost and forgotten? Orientation versus memory in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33 (2):473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Engelborghs S, Maertens K, Nagels G, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: Cross-sectional analysis from a prospective, longitudinal Belgian study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20 (11):1028–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Piguet O, Halliday GM, Creasey H, Broe GA, Kril JJ. Frontotemporal dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies in a case-control study of Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21 (4):688–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Claassen DO, Parisi JE, Giannini C, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Josephs KA. Frontotemporal dementia mimicking dementia with Lewy bodies. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2008;21 (3):157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]