Abstract

Millions face the challenges of caregiving for a loved one with dementia. A classic Glaserian grounded theory methodology was used to discover the problem that caregivers of individuals with dementia face at the end of life and how they attempt to resolve that problem. Data were collected from a theoretical sample of 101 participants through in-person interviews, online interviews, book and blog memoirs of caregivers, and participant observation. Constant comparative method revealed a basic social psychological problem of role entrapment. Caregivers attempt to resolve this problem through a 5-stage basic social psychological process of rediscovering including missing the past, sacrificing self, yearning for escape, reclaiming identity, and finding joy. Health care professionals can support caregivers through this journey by validating, preparing caregivers for future stages, and encouraging natural coping strategies identified in this process. This study provides a substantive theory that may serve as a framework for future studies.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, grounded theory, caregiver, end of life, qualitative research

Introduction

More than 15 million Americans are caring for a loved one with dementia providing a total of over 17.5 billion hours of unpaid care each year. 1 These caregivers live in a state of constant change and disruption. 2 They consistently show high incidence and severity of burden, depression, and physical health deficits throughout the years of caregiving, accruing an additional US$8.7 billion in costs toward their own health care in 2011. 3 –5 Caregiver burden is known to increase as dementia becomes more severe. 6 –8

The impacts of caregiving are holistic and prolonged. Caregivers are susceptible to burden and decreased quality of life, which worsen as dementia becomes more severe. 6 –9 Caregivers of those with dementia are also at high risk for developing depression, and as many as 75% show signs of significant psychological illness. 5 Physical side effects of caregiving may include sleep deprivation, high blood pressure, impaired kidney function, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. 10 –15 Financial costs also leave caregivers struggling long after the death of a loved one, with annual out of pocket expenses for Medicare beneficiaries with dementia averaging nearly US$10 000 and care lasting up to 20 years. 1

Despite continued evidence that this population requires increased support compared to other diseases, caregivers have limited access to end-of-life support programs such as hospice care. 16 –18 Nearly three-quarters of family caregivers reported that they felt relieved when their loved ones with dementia died. 1 Many quantitative studies test the effectiveness of interventions on the incidence and severity of burden, depression, and quality of life among caregivers. 19 –24 Few interventions show consistent results, and service use remains low even for those interventions that are successful, despite reports of high unmet need among caregivers. 25 Few qualitative studies have been conducted on the experience of caregiving for persons with dementia at the end of life, and none of those have used classic grounded theory methodology. Since most caregivers have limited access to end-of-life support or do not seek formal support to meet their needs, it is critical to understand how they process the challenges they face.

The purpose of this study was to discover a substantive theory that identifies the main problem that caregivers of loved ones with dementia face at the end of life and the basic social process by which they resolve that problem. A qualitative paradigm was selected since the goal was to explore a complex phenomenon from the perspectives of those living the experience of caregiving. A classic Glaserian grounded theory methodology was used to inductively unveil a theory that is grounded in data. 26 –32

Method

This research study aimed to explore the following research questions:

What is the chief concern of caregivers of loved ones with dementia at the end of life?

How do caregivers attempt to resolve this problem?

Grounded theory is a method in which a theory is allowed to emerge from data through a constant comparison of evidence. 32 Grounded theory transcends description of data to conceptualize ideas that are substantive. Everything is data, including field work, qualitative or quantitative findings, other relevant literature, and other relevant theories. The wider the spread of data, the more rich and conceptual and accurate the theory will become. Researchers must be theoretically sensitive, letting go of all preconceptions and being open to abstraction of ideas rather than focusing on description. This method utilizes theoretical sampling of the population of interest, in which the researcher selects participants and interview questions based on needs of the emerging theory.

Data are concurrently analyzed as they are collected using constant comparative analysis. Open coding allows the researcher to explore data and search for the primary concern of the population of interest and the core category, or the main process that participants use to overcome this problem. The core category should become apparent to the researcher through continued data collection and analysis. Once it has emerged, the researcher begins to use selective coding to explore the properties of the core variable.

Throughout this process, the researcher writes memos which are stream of consciousness writings to explore the abstract concepts emerging from the data. Theoretical sorting of memos and theoretical coding are used to discover how substantive codes relate to one another. As the researcher continues with these steps, a theory emerges, which guides the researcher until theoretical saturation is reached.

Sample

This study began with a purposive sample of primary caregivers of individuals who passed away in the last 10 years with a self-reported primary diagnosis of dementia, recruited by word of mouth and from fliers to the general public. Theoretical sampling led to recruitment of an online population through postings to targeted message boards and forums. Face-to-face and online interview questions changed as data were analyzed. Memoirs written in books or blogs also emerged as a source of data. Searches were conducted on amazon.com and google.com to collect a sample of memoirs written by informal caregivers of individuals with dementia who had passed away within 10 years. Sections of memoirs were analyzed only if they discussed the last 1 year of the care recipient’s life or time after death.

Caregivers were also observed interacting with loved ones in home and nursing home settings to incorporate participant observation, an important element of grounded theory due to roots in symbolic interactionism. Participant observation also included observation of a support group for current and past spousal caregivers of persons with dementia. At the request of the group leader, only 1 meeting was attended so as not to disrupt the attendance of individuals who may be uncomfortable with researcher presence. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of this sample, excluding the participant observation population for which no demographics were collected to protect patient privacy.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Sample.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample: N = 83 caregivers, N = 86 care recipients | ||

| Caregiver gender (N = 83) | ||

| Male | 11 | 13 |

| Female | 72 | 87 |

| Care recipient gender (N = 86) | ||

| Male | 38 | 44 |

| Female | 48 | 56 |

| Age of caregiver (N = 60) | ||

| Mean: 58 years | ||

| Range: 36-88 years | ||

| Age of care recipient at time of death (N = 74) | ||

| Mean: 80 years | ||

| Range: 47-101 years | ||

| Relationship of care recipient to caregiver (N = 86) | ||

| Father | 20 | 23 |

| Father-in-law | 1 | 1 |

| Friend | 3 | 3.3 |

| Grandfather | 1 | 1 |

| Grandmother | 2 | 2 |

| Husband | 15 | 17 |

| Mother | 38 | 44 |

| Mother-in-law | 3 | 3.3 |

| Wife | 3 | 3.3 |

| Time from diagnosis until death (N = 72) | ||

| Mean: 5 years | ||

| Range: 3 months-21 years | ||

| Time since death (N = 80) | ||

| Mean: 3.9 years | ||

| Range: 3 days-10 years | ||

| Type of dementia (N = 83) | ||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 53 | 64 |

| Frontal temporal lobe | 5 | 6 |

| Lewy body | 7 | 8 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1 | 1 |

| Vascular | 6 | 7 |

| Wernicke-Korsakoff | 1 | 1 |

| Mixed | 3 | 4 |

| Unknown | 8 | 9 |

| Place of death (N = 83) | ||

| Care recipient’s home | 20 | 24 |

| Caregiver’s home | 12 | 17 |

| Home of another family member | 2 | 2 |

| Assisted living | 7 | 8 |

| Nursing home | 31 | 37 |

| Hospital | 8 | 10 |

| Inpatient hospice facility | 2 | 2 |

| Enrolled in hospice at time of death (N = 80) | ||

| Yes | 57 | 71 |

| No | 23 | 29 |

| Time enrolled in hospice (N = 46) | ||

| Mean: 109 days | ||

| Range: 1 day-2 years | ||

| Religious affiliation of caregiver (N = 57) | ||

| Buddhist | 3 | 5 |

| Catholic | 17 | 30 |

| Christian (not otherwise specified) | 13 | 23 |

| Jewish | 1 | 2 |

| Protestant | 14 | 24 |

| Unitarian universalist | 1 | 2 |

| Unaffiliated | 8 | 14 |

| Caregiver racial background (N = 75) | ||

| White | 69 | 92 |

| Hispanic | 3 | 4 |

| African American | 3 | 4 |

In each of these samples, many caregivers communicated through other forms of data than written or spoken word. Caregivers shared photographs of themselves and loved ones, voice mails left by loved ones before death, artwork, obituaries, eulogies from funerals, and meaningful prayers, song lyrics, or links to videos. These sources were all considered data and were analyzed as appropriate.

Data Analysis

Concurrent analysis of books, blogs, interviews, and participant observation data guided selective coding in formal and informal interviews once the core category emerged. Interviews became more targeted as specific questions about the core variable and its properties became relevant, and interviews became shorter as they continued. Memos were written throughout this process as data were collected and coded. Coding occurred line by line, and substantive codes gave way to theoretical codes as analysis continued. Literature review and exploration of existing theories occurred after the core category emerged but prior to the completion of the study, and these were considered data to be examined with reference to the emergent core.

Rigor and Trustworthiness

Lincoln and Guba 33 describe “trustworthiness” as the researcher’s way of building a case to show that these results deserve attention. “Credibility” is analogous to internal validity of quantitative studies. In this study, credibility was ensured through prolonged engagement in research, triangulation of data sources, peer debriefing, and member checking. “Transferability” is analogous to external validity, which was established through thick description, 34 or providing rich and detailed descriptions of data. “Dependability” captures consistency and is analogous to reliability. Dependability was also ensured through triangulation of data sources as well as through keeping an audit trail. “Confirmability” is analogous to objectivity, which was ensured through data abstraction through constant comparison and by having an expert researcher review the audit trail from raw data through analysis.

Other Considerations

This study was approved by the institutional review board prior to recruitment. Informed consent was obtained prior to all in-person and online interviews. Observation participants were given information sheets about the study prior to participation. No informed consent was obtained for use of books or blogs, as these were publically available.

Results

Sample

The total sample included 101 individuals describing 104 cases, including 6 face-to-face interviews with 5 individuals; 60 online interviews with 31 individuals discussing 33 cases, with 1 interview excluded because the participant stated that her loved one had not reached the end of life; 26 books written by 30 caregivers describing 31 cases; and 18 blogs. Participant observation consisted of observations of 18 caregivers. Observations took place over a 2-month period. This sample was primarily female (87%), white (92%), and Christian (77%). Twenty-eight states were represented in the sample, with highest representation from Connecticut (21%).

Role Entrapment

Caregivers faced a concern of being trapped in an inescapable role. They felt bound to loved ones emotionally, mentally, and often physically. One participant said, “I was trapped. I really had no one to take my place. I was an only child with few options since just leaving my mother to fend for herself would have likely resulted in me going to prison.” With or without help from others, caring for this person occupied time, thought, and energy. One daughter said, “Mom was pushing the limits of my energy, every muscle in my being screamed for release.” The primary caregiver believed that he or she held qualities that could not be replaced by others, including information, skills, experience, or love for the family member. One son-in-law said, “You gain solid confidence that you and you alone understand what is really happening.” Since it could not be delegated to others, this nontransferable role could only end through the death of the care recipient. As one son said, “He has to die so I can have my life back.”

Substantive Theory of Rediscovering

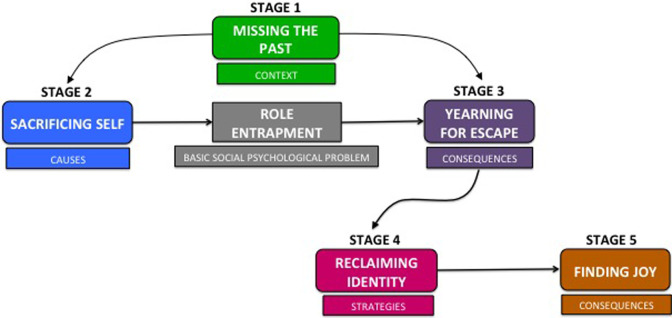

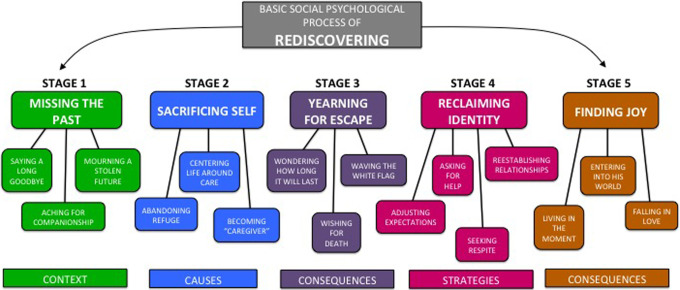

Remaining in this irreplaceable role was simply a fact of caregiving, but individuals could overcome feeling “trapped” in this role through a process of rediscovering. They were able to find some relief by rediscovering the parts of loved ones that remained intact and the parts that were new as dementia progressed, by rediscovering their own identities outside of caregiving, and by rediscovering their relationships with loved ones outside of the caregiver–care recipient dyad. The process of rediscovering consists of 5 stages that emerged from the data. Figure 1 depicts this process, and Figure 2 shows the categories within each stage of this process.

Figure 1.

The basic social psychological process of rediscovering to resolve the basic social psychological problem of role entrapment.

Figure 2.

Categories within the 5-stage process of rediscovering.

Stage 1: Missing the Past

As the care recipient vanished one piece at a time, the caregiver missed the person he or she once knew and loved. Many caregivers described their years of caregiving as “saying a long goodbye.” One daughter wrote, “We sit there every day and watch her die. Our lives are on hold while her death is on hold. We cannot mourn and yet we are forced to grieve every day as another piece of her dies.”

The loss of this loved one to disease created a void in caregivers who missed not only the person but also the relationship they used to have with that person. This was often made worse by the fact that the care recipient no longer recognized the caregiver. “Feeling forgotten” or even “replaced” caused emotional turmoil. One daughter said, “But here is the true heart wrench…when an aide or nurse walks in, I see that look in her eyes for them. They have become her pride and joy.” Participants described feeling “hurt” and “angry.” One life partner wrote, “There were times when I resented people suggesting I focus on trying to find a way to reach him. Couldn’t they understand I also wanted him to reach me?” Another wrote, “I felt like a child, chasing after my mother as she walked away. I just wanted to be loved, for her to take an interest in me, her daughter.”

Missing a loved one and a relationship was compounded by missing a future that should have been and many blamed the disease for “stealing” or “robbing” from them. Caregivers described “shattered dreams” and “life not living up to expectations.” One wife said, “I feel that [he] was cheated, and we were cheated; we were not allowed to grow old together.” Caregivers also felt unmet expectations for their own futures. One said, “I felt ‘robbed’ of some continued type of quality to my personal life and a little independence…” As caregiving continued, sacrifices became greater, which brought caregivers to the second stage of the process.

Stage 2: Sacrificing Self

The context of missing the past laid the groundwork for caregivers to devote themselves to trying to minimize losses and control the “downward spiral” of their loved ones. Ultimately, the identity of the caregiver became dependent on this role, and sense of self outside of caregiving was lost. In turning themselves over to caregiving, participants lost careers, homes, time with their own families, friends, vacations, privacy, and downtime. One wife described the disruption of sharing her home with her husband’s 24-hour caregivers:

Nothing was “ours” or “mine” anymore. I shared the house with [my husband] and with his caregivers. The kitchen, the bathrooms, the living room, the bedroom were theirs. I had virtually no privacy unless it was in the middle of the night and [my husband] was asleep. The dishes, the drawers, the cupboards were no longer just ours, even the newspapers.…I had wanted him home—but I didn’t have a home of my own any more, and that was part of the price I paid.

Another daughter reflected, “I hope when this is all over I still have friends. And a husband. I hope [my children] still have a mom with a sense of humor, and my happiness gene reappears intact.” Many participants used the term “putting life on hold.”

Life became all about caregiving. One daughter said, “You have to remember in this scenario that it’s not really about you. It’s about your loved one(s) and what they need and what’s best for them is the only option.” Participants said, “I was on duty or on call 24/7,” and “It just seemed like I was always on call.” One daughter wrote, “My role as her caregiver was full time, twenty four seven for two years. I had no outside life during my role as a caregiver. My life, was her life.” It did not take long for this grueling job to become an identity. One daughter said, “I was so busy with being a caregiver for my mom…that I often didn’t have the energy or the capacity to be a daughter.” As one summarized, “The role reversal from daughter to caregiver had defined me.”

Stage 3: Yearning for Escape

Ambiguity of prognosis toward the end-of-life period led to caregivers guessing when the end was near and seeing “no end in sight.” One daughter wrote, “I guess what I resent the most is the longevity of the situation. It’s easy to be kind, loving and caring when there’s a cutoff date.” Rather than appreciating this time, caregivers feared what the future might hold if not death. As one participant said, “By the time Mama's life was ending…I just didn’t want her to have to suffer anymore.” Caregivers also wondered how much longer their own suffering would last. Several caregivers admitted that they wished that their loved ones would die. One daughter said, “I think the major feeling is guilt. My mother had dementia for a long time and there were times when I wished she would die and relieve everyone, including herself, of the slow torture of her fading memory.” Another said:

I just want my Dad to be at peace. I can see fear in his eyes. And I just want it to be over for him. Watching him go through this is killing me. This was the first time that I so strongly wanted my Dad to leave this world. It was all I could think about. It's the only solution.

In the midst of physical or emotional anguish, death seemed to be the only way out. Several caregivers considered assisting a loved one in suicide or ending their own lives as a potential way out of their own suffering. One caregiver wondered, “Does the caregiver die first because it’s the only way out?…Oh, how I long to be out of this [world] sometimes.” Another daughter also confessed, “I was alone in caring for my mother and often felt depressed and even suicidal a time or two knowing that I had no one to turn to with questions or for help.” Sleep deprived, emotionally exhausted, and with no reprieve in sight, caregivers struggled to look for rational solutions to the need for escape. Reaching a point of total desperation, caregivers realized that they could no longer continue and began “waving the white flag” and “throwing in the towel.” Many felt “overwhelming shame” and guilt for not living up to their own expectations of being a caregiver.

Stage 4: Reclaiming Identity

After caregivers reached the point of needing escape, they strategized ways to sustain themselves. Caregivers in this stage focused on “forgiving myself,” “going easy on myself,” and “being gentle with myself.” Many had to confront their self-expectations, as they believed asking for help was synonymous with failing to do it themselves. Some described the difficulty of “trusting others to provide good care,” while others struggled to find help. Participants described rejection from hospice care, facilities refusing to take loved ones with behavioral symptoms, and ineligibility from services. Cost was also an insurmountable barrier for many. One daughter sought to have her mother placed in a facility and said, “I basically spent a week fooling myself, thinking that I could find Mother decent care without bankrupting us.” Caregivers exhausted their options and many were left feeling like they were alone. One daughter said, “There was quite simply no help for me as I was caring for my mother.”

If caregivers were able to find help, they used respite time away to “recharge” and “prevent burnout” and to rediscover their own passions and hobbies outside of caregiving. Participants in this stage found a way to “intertwine” roles of caregiver and loved one rather than choosing between them. Participants described rediscovering parts of loved ones that were overlooked while being swallowed up by caregiving. One caregiver wrote, “I WANTED MY MOTHER. I decided it might cheer me up to list a few of the special qualities she exhibited over the years.” After including a long list of her mother’s traits, she divided the list into 3 groups and said, “I realized that I still have a lot of the mother I was describing. Some of the qualities she still has herself.…Some of the qualities reside in my brother.…And some I have inherited.” Others discovered new pieces of their loved ones. One caregiver said, “We were truly beginning to know ‘New [him]’ at another level, and our love grew even stronger.” Another said, “Gradually my need and desire for my ‘old [him]’ began melting away as I realized that I could bring joy to my ‘new [him].’” Caregivers were able to rebuild relationships that had been lost while focusing only on caregiving.

Stage 5: Finding Joy

As a consequence of reclaiming themselves, caregivers were able to find true joy in their roles. Choosing to “live in the moment” allowed caregivers to focus on life, rather than death, even at the end of life. Several described trying to “make the present beautiful” for a loved one. They learned to stop yelling, correcting, and rationalizing. One participant advised, “Enter into their world and you will be happier—if they say it's August and it's really December don’t try to correct them. If they say they haven’t eaten and they just ate give them a snack.”

Caregivers also focused on “finding activities we could do together,” such as coloring, doing puzzles, reading books, listening to music, or just sitting together in a garden. Time was devoted to being together, not just to tasks of caregiving. These connections led to deeper love and understanding. A daughter described:

We became two people in a dance of spirit that included pain, grief, laughter, wonder, frustration, wisdom, and love. My concept of her was annihilated, and in its place I discovered a funny, sharp-witted, sensitive, grateful and loving woman who bore her grief and her trials with great patience and acceptance. She became my hero, my teacher, my model. And in that dance I fell in love with my mother.

Process Variation

Although this process describes a majority of experiences, which occurred in a linear progression, each experience was unique, and not all participants were able to complete the process through to stage 5. In one variation pattern, participants experienced the first 3 stages of this process but could not reclaim their own identities or find joy in their roles. Adult children who described this experience were typically providing care alone and described an upheaval of their entire lives, more often occurring when they cared for a loved one in a home care setting. Spousal caregivers who described this experience described falling out of love with the care recipient because the person whom they loved had completely disappeared. They described feeling “burdened,” “depressed,” and “abused” by their experiences. In another variation, participants described experiencing all stages except stage 3. These caregivers were able to reclaim identity without reaching a “breaking point.” These participants typically began care with a lot of informal support and described finding respite from the start of providing care. Still other participants described experiencing this process as a repeating cycle with each worsening phase of dementia rather than as a linear process, finding joy and then beginning again, reaching new breaking points as the disease progressed.

Discussion of Findings

“Entrapment” is a psychological term with roots in the biological concept of fight versus flight response. 35 Gilbert and Gilbert 36 describe entrapment as an arrested flight response, usually caused by a prolonged stress that is perceived to be uncontrollable and inescapable. 35 According to Gilbert and Allan’s 37 entrapment scale, external entrapment is based on such feelings as feeling trapped, feeling like one can’t get out, wanting to escape, and feeling powerless in a situation or relationship.

One descriptive quantitative study explored the construct of “entrapment” as well as depression, guilt, and shame among 70 caregivers of individuals with dementia in England. 38 Entrapment was correlated with depression (r = .602, P = .001) and with shame (r = .344, P = .01) but not with guilt. Several qualitative studies reference feelings that reflect role entrapment of caregivers but do not use this term. A content analysis of focus group interviews in Norway identified the following 3 categories: “To be stuck in it—I can’t just leave”; “it assaults one’s dignity”; and “sense of powerlessness in relation to the fragmentation of relationships in home health care.” 39(p220) Feeling stuck and powerless both reflect concepts within the construct of entrapment. Other studies reflect a perception among caregivers that they are expected by societal standards to become caregivers. 40,41 Among caregivers in the current study, many participants also reported feeling trapped by the feeling that only they could provide good quality of care for their loved ones. The belief that quality of care depends on the presence of a family caregiver is consistent with previous studies. 42 –45

Understanding the problem of role entrapment and the process of rediscovering gives health care professionals (HCPs) insight and tools to help caregivers find joy and provide joy to loved ones at the end of life. Recognizing the caregiver’s current stage allows HCPs to validate the feelings that the caregiver expresses and help caregivers anticipate what they might experience next. The HCPs should also know that caregivers in all stages are at risk of depression and suicide. Particularly in stage 3, caregivers should be assessed for suicidal ideation.

It is also important for HCPs to be mindful of implicit expectations that they place on caregivers. Many caregivers felt trapped by expectations that they would care for a loved one independently and would provide care at home. Although these expectations are often self-imposed, previous studies indicate that HCPs often unintentionally reinforce these ideas to caregivers. 42,46 The HCPs should recognize that caregivers need support from the beginning of the process through to the end. For most participants in this study, this process lasted significantly longer than 6 months, which is the eligibility period for hospice care. Eligibility criteria for the Medicare Hospice benefit must be reexamined for this population. 17,47 –50

Measuring incidence and severity of role entrapment may be helpful in assessing populations of caregivers at risk of depression, as well as in evaluating effectiveness of interventions to provide caregiver support at the end of life. Future studies should focus on developing interventions to support and bolster those coping strategies that caregivers already use to transition through stages of this process. For example, using a participant’s own strategy of listing her mother’s qualities and identifying where she could find these qualities in others may aid other caregivers in reestablishing relationships. Studies should also explore categories that emerged from this study but that did not occur within the process of rediscovering. Other categories that competed with “role entrapment” as potential basic social psychological problems that may warrant future study include “bearing witness to suffering,” “life disruption,” “navigating systems,” and “filling the void after death.” The applicability of this process to individuals from racial and ethnic backgrounds other than white caregivers should also be explored.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had several limitations. This sample lacked diversity in racial and religious backgrounds. The use of published memoirs as data may have also skewed results toward a more educated population. It is worth noting, however, that most of these books were self-published and the diversity of writing styles and grammar usage appeared to indicate a spread of educational backgrounds. Another limitation of this study may have been including both spousal caregivers and adult-child caregivers in the same sample. Although this decision was consciously made to add breadth to the theory, the inclusion of both groups may have weakened the ability to construct a theory that specifically fit each population. This study was strengthened by strict adherence to grounded theory methodology and triangulation of data sources that added insight and objectivity that could not be possible from using 1 data source alone.

Caregivers who were able to work through this process were able to transcend providing care and were able to provide joy to the care recipient and themselves. The HCPs must recognize and understand this process as a means to help caregivers overcome feeling stuck and trapped and move toward finding happiness again.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr Cheryl Beck for mentorship throughout this study, and Dr Thomas Long and Dr Colleen Delaney for editing and support.

Footnotes

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Alzheimer's Association. 2013. Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. http://www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2013.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Prorok JC, Horgan S, Seitz DP. Health care experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers: a meta-ethnographic analysis of qualitative studies. CMAJ. 2013;185(14):E669–E680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alzheimer's Association. Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(2):131–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Papastavrou E, Charalambous A, Tsangari H, Karayiannis G. The burdensome and depressive experience of caring: what cancer, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer's disease caregivers have in common. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(3):187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prince M, Jackson J. World Alzheimer report 2009. Alzheimer's Disease International Web site. http://www.med.upenn.edu/aging/documents/WorldAlzheimerReportdesignedvers9-2-09.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2014.

- 6. Kim H, Chang M, Rose K, Kim S. Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(4):846–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu J, Wang L, Tan J, et al. Burden, anxiety and depression in caregivers of veterans with dementia in Beijing. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(3):560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Turró-Garriga O, Garre-Olmo J, Vilalta-Franch J, Conde-Sala J, M, López-Pousa S. Burden associated with the presence of anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(3):291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vellone E, Piras G, Venturini G, Alvaro R, Cohen MZ. The experience of quality of life for caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease living in Sardinia, Italy. J Transcult Nurs. 2012;23(1):46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Capistrant BD, Moon JR, Berkman LF, Glymour MM. Current and long-term spousal caregiving and onset of cardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(10):951–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion E, Roepke SK, et al. A longitudinal analysis of the relations among stress, depressive symptoms, leisure satisfaction, and endothelial function in caregivers. Health Psychol. 2012;31(4):433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chattillion EA, Ceglowski J, Roepke SK, et al. Pleasant events, activity restriction, and blood pressure in dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2013;32(7):793–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Effect of chronic dementia caregiving and major transitions in the caregiving situation on kidney function: a longitudinal study. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(2):214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cupidi C, Realmuto S, Lo Coco G, et al. Sleep quality in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease and its relationship to quality of life. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(11):1827–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simpson C, Carter P. Dementia behavioural and psychiatric symptoms: effect on caregiver's sleep. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(21):3042–3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Godwin B, Waters H. ’In solitary confinement’: planning end-of-life well-being with people with advanced dementia, their family and professional carers. Mortality. 2009;14(3):265–285. [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCarty CE, Volicer L. Hospice access for individuals with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dementias. 2009;24(6):476–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller SC, Lima JC, Mitchell SL. Hospice care for persons with dementia: the growth of access in US nursing homes. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dementias. 2010;25(8):666–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bakker TJ, Duivenvoorden HJ, Olde Rikkert M, Beekman AT, Ribbe MW. Integrative psychotherapeutic nursing home program to reduce multiple psychiatric symptoms of cognitively impaired patients and caregiver burden: randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bass DM, Judge KS, Snow LA, et al. Caregiver outcomes of partners in dementia care: effect of a care coordination program for veterans with dementia and their family members and friends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1377–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chien LY, Chu H, Guo JL, et al. Caregiver support groups in patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(10):1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang HL, Kuo LM, Chen YS, et al. A home-based training program improves caregivers’ skills and dementia patients’ aggressive behaviors: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(11):1060–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim K, Zarit SH, Femia EE, Savla J. Kin relationship of caregivers and people with dementia: stress and response to intervention. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(1):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347(3934):f6276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phillipson L, Magee C, Jones SC. Why carers of people with dementia do not utilise out-of-home respite services. Health Soc Care Commun. 2013;21(4):411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glaser BG. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glaser BG. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Glaser BG. The Grounded Theory Perspective: Conceptualization Contrasted With Description. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glaser BG. The Grounded Theory Perspective II: Description’s Remodeling of Grounded Theory Methodology. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glaser BG. The Grounded Theory Perspective III: Theoretical Coding. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Glaser BG. Getting Out of the Data: Grounded Theory Conceptualization. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction; 1967/2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Geertz C. Thick description: toward an interpretive theory of culture. In: The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1973:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taylor PJ, Gooding P, Wood AM, Tarrier N. The role of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety, and suicide. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(3):391–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gilbert P, Gilbert J. Entrapment and arrested fight and flight in depression: an exploration using focus groups. Psychol Psychother Theor Res Pract. 2003;76(pt 2):173–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gilbert P, Allan S. The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: an exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):584–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martin Y, Gilbert P, McEwan K, Irons C. The relation of entrapment, shame and guilt to depression, in carers of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(2):101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Landmark BT, Aasgaard H, Svenkerud Fagerström L. “To be stuck in It—I can’t just leave”: a qualitative study of relatives’ experiences of dementia suffers living at home and need for support. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2013;25(5):217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee Y, Smith L. Qualitative research on Korean American dementia caregivers’ perception of caregiving: heterogeneity between spouse caregivers and child caregivers. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2012;22(2):115–129. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lin M, Macmillan M, Brown N. A grounded theory longitudinal study of carers’ experiences of caring for people with dementia. Dementia. 2012;11(2):181–197. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benedetti R, Cohen L, Taylor M. “There’s really no other option”: Italian Australians’ experiences of caring for a family member with dementia. J Women Aging. 2013;25(2):138–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mullin J, Simpson J, Froggatt K. Experiences of spouses of people with dementia in long-term care. Dementia. 2013;12(2):177–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Phillipson L, Magee C, Jones SC. Why carers of people with dementia do not utilise out-of-home respite services. Health Soc Care Community. 2013;21(4):411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shanley C, Russell C, Middleton H, Simpson-Young V. Living through end-stage dementia: the experiences and expressed needs of family carers. Dementia. 2011;10(3):325–340. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Robinson A, Lea E, Hemmings L, et al. Seeking respite: issues around the use of day respite care for the carers of people with dementia. Ageing Soc. 2012;32:196–218. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Covinsky KE, Yaffe K. Dementia, prognosis, and the needs of patients and caregivers. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):573–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kiely DK, Givens JL, Shaffer ML, Teno JM, Mitchell SL. Hospice use and outcomes in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12):2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, Park PS, Morris JN, Fries BE. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2734–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lewis LF. Caregivers’ experiences seeking hospice care for loved ones with dementia. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(9):1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]