Abstract

Person-centered care (PCC) has been the subject of several intervention studies reporting positive effects on people with dementia. However, its impact on staff remains unclear. The purpose of this systematic review was to assess the impact of PCC approaches on stress, burnout, and job satisfaction of staff caring for people with dementia in residential aged care facilities. Research articles published up to 2013 were searched on PubMed, Web of Knowledge, Scopus, and EBSCO and reference lists from relevant publications. The review was limited to experimental and quasi-experimental studies, published in English and involving direct care workers (DCWs). In all, 7 studies were included, addressing different PCC approaches: dementia care mapping (n = 1), stimulation-oriented approaches (n = 2), emotion-oriented approaches (n = 2), and behavioral-oriented approaches (n = 2). Methodological weaknesses and heterogeneity among studies make it difficult to draw firm conclusions. However, 5 studies reported benefits on DCWs, suggesting a tendency toward the effectiveness of PCC on staff.

Keywords: residential aged care facilities, dementia, direct care workers, person-centered care, systematic review

Introduction

Dementia affects nearly 35.6 million people worldwide, and this number is projected to rise as the population ages. 1 Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), such as agitation and wandering, emerge in a significant number of cases, with almost 90% of people with dementia developing at least 1 BPSD. 2 These symptoms are often distressing for informal caregivers and greatly increase the likelihood of care recipients’ admission to residential aged care facilities (ie, homes for the aged, assisted living facilities, or nursing homes). 3 Also, BPSD are one of the main causes of stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction among direct care workers (DCWs) who provide the bulk of care to people with dementia in residential aged care facilities. 4,5

Between one-half and two-thirds of care home residents have some form of dementia, and these numbers will escalate rapidly in coming years. 6 –8 The increasing prevalence of dementia has challenged residential aged care facilities to recognize the need to go beyond the medical and supervisory care that has traditionally provided the rationale for their existence and in recent years, growing attention has been paid to the concept of person-centered care (PCC) as a key approach to creating a more positive psychosocial environment for residents with dementia. 9 The term PCC had its origins in the work of Carl Rogers and client-centered therapy. 10 His approach was an evolution from the medical model of the practitioner as an expert figure to one that validates the individual with the illness and recognizes their strengths and needs. 10 Rogers advocated a change to the traditional therapeutic relationships, with more emphasis on the person and less on the care task. 11

Later, it was Tom Kitwood who encouraged PCC approach in dementia care. Kitwood 12 argued that BPSD were not just the result of changes in the brain but a consequence of a complex interaction between neuropathology and the person’s psychosocial environment. Within this conceptualization, many of the difficulties people with dementia experience are not just a consequence of the disease itself but are the result of threats to one’s personhood, brought about by negative interactions with others. Kitwood 12 termed this “malignant social psychology.” Examples of a malignant social psychology include infantilization, disempowerment, or objectification and are often seen as a product of the DCW’s limited skills in communicating adequately with the person with dementia. 12,13 Thus, Kitwood 12 emphasizes the relational nature of PCC and the need to value carers, that is, the provision of PCC is not possible unless carers themselves have communication skills; their own emotional strains are recognized; and they experience feelings of being respected and valued.

His framework provided an important theoretical rationale for the development of different forms of approaches to dementia care, 14 such as behavior-oriented approaches (eg, simplify tasks and provide 1-step instructions); emotion-oriented approaches (eg, reminiscence and validation therapy); cognition-oriented approaches (eg, reality orientation); and stimulation-oriented approaches (eg, recreational therapies and multisensory stimulation; Table 1).

Table 1.

Approaches Based on PCC. 14

| Approaches | General Description |

|---|---|

| Behavioral-oriented approaches | • Manage disabilities and problem behaviors using principles of learning (eg, scheduled toileting) |

| Emotion-oriented approaches | |

| • Reminiscence therapy and life story | • Stimulate memory and mood in the context of the resident’s life history. |

| • Validation therapy | • Restore self-worth and reduce stress by validating emotional ties to the past. |

| • Simulated presence therapy | • Alleviate problem behaviors by playing an audio or videotape to a person with dementia that has been personalized by his or her caregiver. |

| Cognition-oriented approaches | |

| • Reality orientation | • Manage disorientation and confusion through regular stimulation and repetition of basic orientation (eg, calendars and clocks). |

| • Skills training | • Restore specific cognitive deficits through structured activities. |

| Stimulation-oriented approaches | |

| • Multisensory stimulation/snoezelen | • Stimulate the senses using lighting effects, color, sounds, music, or scents in order to obtain maximum pleasure from the activity in which people are involved. |

| • Art therapies | • Provide meaningful stimulation and improve social interaction through dancing, drawing, painting, etc. |

| • Recreational activities/therapies | • Engage in pleasant activities such as crafts or games as a way of facilitating the individual’s need for communication, self-esteem, sense of identity, and productivity. |

| • Aromatherapy | • Use of natural oils to enhance psychological and physical well-being. |

| Exercise | • Engage in sport activities to improve psychomotor function and social interaction. |

Abbreviation: PCC, person-centered care.

Providing DCWs with education and training to deliver PCC approaches have typically been used as the means to improve quality of care for people with dementia. Studies have showed positive effects of PCC on different outcomes among residents, including a decrease in the use of chemical restraints 15 ; less resident agitation and aggression 16 ; fewer falls 17 ; and an increase in residents’ participation during care routines. 18 However, the relationship between the outcomes of PCC and DCWs, including stress, burnout, and job satisfaction, remains understudied. 19 Considering the relational nature of PCC, one might assume that this approach has benefits not only for the care receiver but also for the DCWs.

A recent systematic literature review conducted by van den Pol-Grevelink et al 20 concluded that there are limited indications that PCC has a positive effect on DCWs’ job satisfaction. Despite its valuable contribution to the current state of knowledge in this field, this review was not specifically focused on DCWs providing care for residents with dementia but targeted to all care home residents, and it only included studies conducted in Dutch nursing homes. Furthermore, the authors overextended the construct of job satisfaction by considering the job stress and burnout as components of the former. Such conceptualization seems to disregard the significance and independence of each one of these variables.

The increasing demand for more and higher quality services highlights the need to address the psychological pressure experienced by care staff, as this can also affect the process of caring for people with dementia. 13 Stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction among DCWs have been recognized in a number of studies as the most important threats to the care provision as well as to the well-being of the worker and the resident. 5,21,22

The aim of the present systematic review was therefore to assess the impact of PCC approaches on stress, burnout, and job satisfaction among DCWs providing care for residents with dementia in residential aged care facilities, in order to add to knowledge about the impact of PCC on DCWs and to determine whether specific interventions are of benefit.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Types of studies

Since the present review is one of the first attempts to study the association between PCC approaches and outcomes for staff, and it is anticipated that the effects of interventions are unlikely to be studied only in randomized trials, both randomized and nonrandomized studies were considered. Concerning the latter, the following designs were eligible: controlled before-and-after studies; and uncontrolled before-and-after studies and posttest studies. Studies had to be written in English and published in a scholarly peer-reviewed journal. Nonexperimental studies (eg, observational studies), reviews, letters, notes, case reports, or qualitative studies were not considered.

Types of participants

Studies were eligible if they included mainly DCWs providing care to people with dementia in residential aged care facilities as participants. A number of designations for DCWs were included nursing assistant/aid, personal care attendant, attendant care worker, personal assistant, or frontline staff. Given the lack of research in this area, certified nursing assistants/aids (CNAs) were also considered eligible in order to obtain a large number of studies. As DCWs, CNAs are responsible to assist residents with activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing, grooming, and eating, however, they are required to be certified after completing a specialized training.

Types of interventions

The interventions of interest consisted of interventions in dementia care distinguished by American Psychiatric Association 14 as reflecting a person-centered philosophy of care, that is, in which an understanding of the individual is emphasized, and strategies such as behavior-oriented approaches, emotion-oriented approaches, cognition-oriented approaches, and stimulation-oriented approaches are employed to improve the person’s quality of life and maximize function in the context of existing deficits. Dementia care mapping (DCM) utilizes systematic observations to evaluate the quality of care and well-being of people with dementia in formal care settings. 23 As DCM can be used to help staff understand the experience of people with dementia and change practices, it was also considered in this review. In order to ensure that studies actually reflected a PCC, they should explicitly mention to be focused on PCC, that is, employ the terms person-/patient-/client-/relationship-centered care or emphasize that the choice of the approach was based on the resident’s characteristics and preference.

Interventions were assigned to only 1 category even if more than 1 would have been appropriate in some cases. When this happened, 2 authors (A.B. and D.F.) met to reach an agreement.

Types of outcomes

Broad variables that are considered important threats to the care provision and that may offer an initial picture of the impact of PCC on staff well-being were selected. Therefore, the primary outcomes that were considered for review were DCWs’ stress, burnout, and job satisfaction. Studies were not required to address all these outcomes to be eligible for inclusion. Stress has been defined as a physiological and psychological response experienced when the demands of a situation tax or exceed a person’s resources and some type of harm or loss is anticipated. 24 Long-term exposure to stress may result in burnout, a state of emotional exhaustion (feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted), depersonalization (cynicism or callous attitude towards others), and lack of personal accomplishment (negative assessment of one’s competence and work achievements). 25 Job satisfaction reflects how people feel about the different dimensions of their jobs. 26

Search Strategy

Research articles published from the inception of the database up to 2013 were searched on the electronic databases PubMed, Web of Knowledge, Academic Search Complete—EBSCO and Scopus, between December 2012 and March 2013.

The following strategy created for PubMed was adopted for each one of the other databases: Dementia [MESH] AND residential facilities [MESH] AND (behavior therapy OR emotion-oriented OR validation therapy OR reminiscence OR simulated presence OR cognitive-oriented OR reality orientation OR skills training OR stimulation-oriented OR multi-sensory stimulation OR aromatherapy OR sensory stimulation OR snoezelen OR recreational therapy OR art therapy OR activity therapy OR person cent* OR patient cent* OR client cent* OR relationship cent* OR dementia care mapping).

The bibliography of all potential relevant articles was also used to identify additional articles.

Selection of Studies

Search results obtained from the databases were combined using the software Endnote version X5, and duplicate records were removed. Afterward, the titles and abstracts of the identified references were screened for relevance by the first author (A.B.), considering the established eligibility criteria. The full text of the potentially relevant articles was obtained and screened to determine its inclusion in the review. If information about the potentially relevant study was lacking or unclear, the corresponding authors were contacted to request further details. The final decision about the studies to be included was confirmed by the last author (D.F.).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The following details of the included studies were extracted and summarized by the first author (A.B.): authors and year of publication, country, study design, type and description of the intervention, sample, outcomes, and main results. A second researcher (D.F.) independently checked the data extraction for accuracy and detail. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the 2 authors. Each study was independently reviewed for methodological quality by 2 authors (A.B. and D.F.), using the assessment tool recommended by Cochrane. 27 The following criteria were considered: selection bias (method of randomization and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), and reporting bias (selective outcome reporting).

The decision whether the criteria were fulfilled (“yes”) or not (“no”) was based on the information provided in the article, and if this information was inadequate, the decision was labeled “unknown” (“?”).

Data Synthesis

Given the variability among studies regarding study design, interventions, and measuring outcomes, a qualitative analysis was employed to synthesize the findings. This relies primarily on the use of text to summarize and explain the findings of multiple studies. 28

Results

Overview of Results

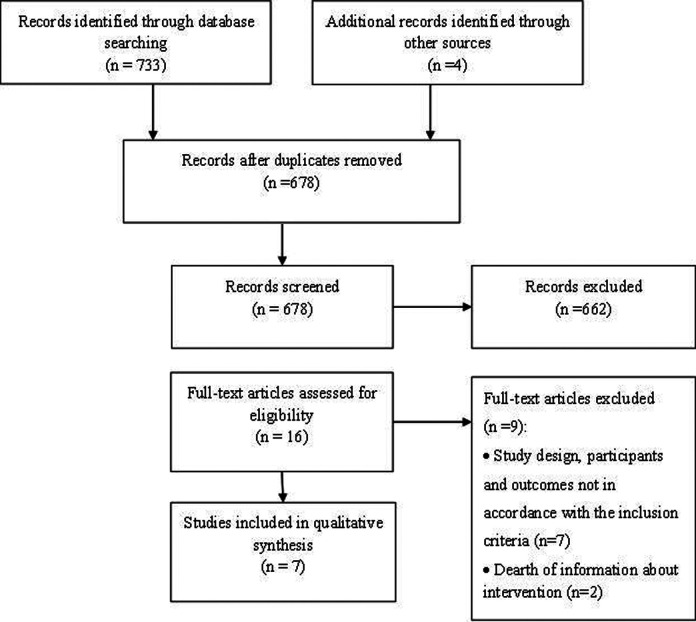

A total of 678 references were initially identified. Based on their titles and abstracts, a total of 16 references were acknowledged as potentially eligible, while 662 were excluded. Nonexperimental studies, interventions implemented in settings other than residential aged care facilities, and studies not focused on dementia were identified as the main reasons for exclusion. The full article of the 16 potentially relevant studies was obtained. After a complete reading, 9 references were excluded from the review. 29 –37 Reasons for exclusion included participants or outcomes were not in accordance with those established in the inclusion criteria 30,32,35 –37 ; study design did not meet defined criteria 33,34 ; or there was dearth of information about the intervention. 29,31 Although these 2 studies were possibly relevant, no response was obtained from the authors in order to clarify the intervention, thus, they were excluded from the review. A total of 7 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of Studies Procedure

Characteristics of Included Studies

The 7 included studies addressed different PCC approaches, including DCM 38 ; stimulation-oriented approaches, such as recreational therapy (storytelling) or multisensory stimulation (snoezelen) 39 ; emotion-oriented 40,41 ; and behavioral-oriented approaches. 38,42,43

Of the 7 studies, 3 were originated from the Netherlands, 39 –41 2 from the United States, 42,44 1 from Canada, 43 and 1 from Australia. 38 The number of participants ranged from 26 to 300 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Selected Studies.

| Source | Methods | Approach | Participants | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finnema et al 40 | Design: RCT. Measurement: 1 month before and 7 months after the intervention. | Emotion-oriented | Sample: 99 nursing assistants (46 intervention group; 53 control group). Setting: 16 psychogeriatric wards in 14 nursing homes. Country: the Netherlands | Stress: GHQ-28 | Positive significant differences in favor of the intervention group for stress (P < .05). |

| Fritsch et al 44 | Design: post-only study with a group control. Measurement: 2 weeks after the intervention. | Stimulation-oriented | Sample: 192, including 67% of nursing assistants. Setting: 20 nursing homes. Country: United States | Burnout: MBI. Job satisfaction: 5 indicators adapted from Montgomery (1993) | No significant differences were observed for job satisfaction and burnout. |

| Jeon et al 38 | Design: RCT. Measurement: before, after, and 4 months after the intervention. | Dementia care mapping | Sample: 124 (43.5% nursing assistants). Setting: 15 residential aged care sites. Country: Australia | Burnout: MBI. Stress: GHQ-12 | Significant decreases in emotional exhaustion (MBI; P < .05). No significant decrease in depersonalization (MBI) in both intervention groups. Significant time effect for stress, which increased at postintervention but declined at follow-up. |

| Passalacqua and Harwood 42 | Design: quasi-experimental, pre and post without control group. Duration: 14 weeks. Measurement: 4 weeks before and 6 weeks after the intervention. | Behavior-oriented | Sample: 26 DCWs. Setting: 1 home for the aged. Country: United States | Burnout: MBI (emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales) | Positive significant differences for depersonalization (P < .05). |

| Schrijnemaekers et al 41 | Study: RCT. Duration: 16 months. Measurement: pre-, 3, 6, and 12 months postintervention. | Emotion-oriented | Sample: 300 caregivers (155 of intervention group, 145 of control group). Setting: 16 homes for the aged. Country: the Netherlands | Job satisfaction: 5 of 7 subscales of Maastricht Work Satisfaction Scale for Healthcare (MAS). Burnout: MBI | Short-term differences in favor of the intervention group. Differences were statistically significant for 2 subscales of job satisfaction–“opportunities for self-actualization” and “contact with residents”—and 1 subscale of burnout—“personal accomplishment” (P < .05). Findings were not consistent over time. |

| van Weert et al 39 | Design: quasi-experimental, pre- and posttest control group. Duration: 19 months. Measurement: before and 18 months postintervention. | Stimulation-oriented | Sample: 127 certified nursing assistants (64 of intervention group; 63 of control group). Setting: 6 nursing homes. Country: the Netherlands | Job satisfaction: 4 of 7 subscales of MAS. Stress: GHQ-12. Burnout: MBI | Job satisfaction: positive significant differences in favor of the intervention group for satisfaction with quality of care (P < .001), contact with residents (P < .01) and total satisfaction (P < .01). Stress: positive significant differences in favor of the intervention group (P < .05). Burnout: positive significant differences in favor of the intervention group for emotional exhaustion (P < .05). |

| Wells et al 43 | Design: quasi-intervention, repeated measures design. Duration: 12 months. Measurement: baseline, 3, and 6 months postintervention. | Behavior-oriented | Sample: 44 nursing staff (16—7 care assistants on the intervention group and 28—13 care assistants on the control groups). Setting: 4 nursing home units. Country: Canada | Stress: Hassles subscale of the Nurses Hassles and Uplifts Scale (41 item) | No effect on staff level of stress. |

Abbreviations: GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; RCT, randomized controlled trial; DCW, direct care worker.

None of the 7 studies met all the quality criteria (Table 3). Of the 7 studies, 4 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). 38,40,41,44 Residential aged care facilities were selected as the unit of randomization, yet information about the method for the allocation concealment was unclear. It was not possible to blind residents due to the nature of the interventions; however, an effort to blind outcome assessors was made in Wells et al. 43 Most studies (n = 5) lacked follow-up assessments. For those which had, 38,41 the time periods varied from 4 months 38 to 1 year. 41 Only Schrijnemaekers et al 41 stated that they used intention-to-treat analysis. In the remaining studies, data were collected only from the “completers.” In the studies by Passalacqua and Harwood 42 and Fritsch et al, 44 selective reporting was apparent as one or more outcomes were not reported. In the study by Passalacqua and Harwood, 42 it was stated in the methodology that Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) was used to assess burnout; however, the authors have only reported the results obtained for 1 subscale—depersonalization. In the study by Fritsh et al, 44 job satisfaction and burnout were reported in the methodology but insufficient detail about their findings was present in the Results’ section. There was a risk of other bias in van Weert et al study 39 as the dropouts during the study were replaced by new staff members. Therefore, the treatment duration periods were unequal for patients in the original group and the replacement group, which do not allow intention-to-treat analysis.

Table 3.

Methodological Quality of the Included Studies.

| Randomization | Allocation Concealment | Blinding of Participants and Personnel | Blinding of Outcome Assessors | Incomplete Outcome Data Addressed | Free of Selective Reporting | Free of Other Bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fritsch et al 44 | + | ? | ? | ? | − | + | − |

| Finnema et al 40 | + | ? | − | − | − | + | + |

| Jeon et al 38 | + | ? | − | ? | − | + | + |

| Passalacqua and Harwood 42 | − | − | ? | ? | − | − | + |

| van Weert et al 39 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Schrijnemaekers et al 41 | + | ? | − | − | + | + | + |

| Wells et al 43 | − | − | ? | + | − | + | + |

Abbreviations: +, yes (low risk of bias); −, no (high risk of bias); ?, unclear.

Outcome measures

Of the 7 studies, 5 assessed burnout, 38,39,41,42,44 4 measured staff’s stress, 38 –40,43 and 3 measured job satisfaction. 39,41,44 In the 5 studies that had assessed burnout, the MBI was the instrument used. The Maastricht Work Satisfaction Scale for Healthcare (MAS) was selected in 2 studies to assess job satisfaction. 39,41 In 1 study, this outcome was assessed using an adaptation of the scale of Montgomery. 44 The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) was used in 3 studies to assess the levels of stress. 38 –40 There was little consistency in the use of the outcome measures. Finnema et al 40 used the full version of GHQ (28 items), while Jeon et al 38 and van Weert et al 39 administered the short version of the scale (12 items). van Weert et al 39 selected 4 of the 7 subscales of MAS (satisfaction with quality of care, opportunities for self-actualization, contact with colleagues, and contact with residents), while Schrijnemaekers et al 41 selected 5 subscales (satisfaction with the head of the ward, quality of care, opportunities for self-actualization/growth, and contact with colleagues and residents). Of the 3 subscales of MBI “emotional exhaustion,” “depersonalization,” and “personal accomplishment,” van Weert et al 39 excluded the depersonalization subscale from the analysis (Table 2).

Effects of PCC Approaches on DCWs’ Outcomes

Stimulation-oriented interventions

Two different studies fell into this group. van Weert et al, 39 through a quasi-experimental pretest–posttest design, investigated the effectiveness of integrated snoezelen on work-related outcomes of staff in nursing homes. The intervention consisted of a 4-day in-house training program, 3 follow-up meetings, and 2 general meetings to support the implementation of snoezelen in daily care. Data collected at baseline and after 18 months indicated that the implementation of snoezelen was significantly associated with a reduction in stress (intervention group: before intervention (t0) mean (M) = 1.46, standard deviation (SD) = 0.4; after intervention (t1) M = 0.77, SD = 0.4; control group: t0 M = 1.24, SD = 0.4; t1 M = 1.93, SD = 0.4), job dissatisfaction (intervention group: t0 M = 53.36, SD = 0.97; t1 M = 56.41, SD = 1.6; control group: t0 M = 54.33, SD = 1.6; t1 M = 52.87, SD = 1.6), and emotional exhaustion on staff (intervention group: t0 M = 10.75, SD = 0.8; t1 M = 8.31, SD = 0.9; control group: t0 M = 10.35, SD = 0.8; t1 M = 10.77, SD = 0.9).

Fritsch et al 44 evaluated the impact of a group storytelling approach on people with dementia and care assistants. A posttest-only study with a group control was conducted. Staff (n = 192) received a 10-week on-site training on how to implement storytelling. Outcomes were assessed 2 weeks after the intervention. No effects on staff’s burnout or job satisfaction among either the intervention or control group were observed (Table 2).

Emotion-oriented interventions

Two studies fell into this group. Finnema et al 40 used a pretest–posttest control group design to examine the effect of integrated emotion-oriented care (an approach that applies validation in combination with other interventions such as reminiscence and sensory stimulation) on both nursing home residents with dementia and staff. Staff in the intervention group received training and supervision in emotion-oriented care for more than 9 months. The following courses were offered: (1) basic training on emotion-oriented care for all staff members involved in care; (2) advanced course “emotion-oriented care worker” for 5 staff members; and (3) a training course “adviser emotion-oriented care” for 1 staff member. Data were gathered at baseline and after 7 months. Findings indicated a significant decrease in stress in those who perceived improvements in their emotion-oriented care competences (intervention group: t0 M = 15.14, SD = 7.9; t1 M = 14.77, SD = 6.8; control group: t0 M = 16.92, SD = 12.2; t1 M = 19.25, SD = 9.8).

Also, Schrijnemaekers et al 41 studied the effect of emotion-oriented care on staff through a pre–post RCT. The 8 facilities of the experimental group received (1) clinical lessons (for all employees); (2) a 6-day training program (for 8 workers in each facility); and (3) 3 supervision meetings (half-a-day each) held over 4 months after training. Data were gathered at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months’ follow-up. Based on a sample of 300 care assistants, the authors observed significantly positive effects in favor of the intervention groups on burnout (subscale of personal accomplishment) and some aspects of staff’s job satisfaction (“opportunities for self-actualization”—intervention group: t0 M = 7.3, SD = 2.3; control group: t0 M = 8.0, SD = 1.8), though the findings were not consistent over time (Table 2).

Behavioral-oriented approaches

Two different studies fell into this group. Passalacqua and Harwood 42 assessed the effects of a communication skill training for 26 DCWs through a quasi-experimental pre- and postintervention without the control group. The intervention was offered in four 1-hour workshops over a period of 4 weeks, with each workshop devoted to 1 of the 4 elements of Brooker’s 23 VIPS model (Valuing people and those who care for them; treating people as Individuals; looking at the world from the Perspective of the person with dementia; and creating a positive Social environment) and to communication skill training. Findings suggested a significant reduction in 1 aspect of burnout—depersonalization (t0 M = 1.71, SD = 1.36; t1 M = 1.16, SD = 0.43).

Wells et al 43 implemented a behavioral approach consisting of training staff through 5 educational sessions to use an abilities-focused morning care routine with residents. Specifically, staff were taught to give residents verbal prompts before carrying out care tasks and to help them to carry out care tasks as independently as possible. Data were gathered at baseline and at 3 and 6 months postintervention. Findings suggested an absence of impact on staff’s stress levels (Table 2).

Dementia-care mapping

Jeon et al 38 through an RCT conducted in 15 aged care facilities assessed the efficacy of DCM and PCC on staff stress and burnout. The DCM intervention consisted of training 45 staff members (42.2% nurse assistants) on DCM and skills to implement PCC-based care practices. The intervention required intensive 6 to 8 hours of systematic observations of individual residents and their interactions with staff. Burnout and stress were assessed at 3 time points: prior to the intervention, immediately postintervention, and at 4 months’ follow-up. Significant decreases for emotional exhaustion, a subscale of MBI, were only obtained at postintervention among the staff of the DCM group (DCM: t0 M = 17.3, SD = 1.7; and t1 M = 14.8, SD = 1.8; PCC: t0 M = 14.3, SD = 1.5; and t1 M = 16.0, SD = 1.7; control: t0 M = 12.4, SD = 2.3; and t1 M = 14.5, SD = 2.5).This outcome also declined significantly with time only in the DCM group (DCM: F 2.82 = 5.49, P = .006; PCC: F 2.102 = 0.28, P = .76; control: F 2.40 = 0.96, P = .39). MBI personal accomplishment rose significantly over time for all groups, but no differences were found between them. Although not significant, results for the measures of depersonalization tended to drop from baseline to follow-up only for the intervention groups. For all groups, there was a significant time effect for stress, which increased at postintervention but declined at follow-up. Yet, time effect did not differ between clusters. Findings need to be interpreted with caution, given that the values are not specific for DCWs but rather to the whole group of staff (Table 2).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the impact of PCC approaches to dementia care on DCWs’ stress, burnout, or job satisfaction. A total of 7 studies were included, which assessed a range of PCC approaches: emotion-oriented approaches (n = 2); stimulation-oriented approaches (n = 2); behavioral-oriented approaches (n = 2); and DCM (n = 1). Differences in the type of design, outcomes, number of participants, and duration of intervention hindered study comparisons and generalizations. Moreover, a range of methodological weaknesses make it difficult to provide any conclusive indication of the effectiveness of these approaches.

Nonetheless, findings point to a potentially important benefit of such approaches for staff, as most studies (n = 5) reported significant positive changes in the outcome domains. Each of the 2 RCTs that assessed emotion-oriented approaches were successful in reducing DCWs’ stress, 40 burnout, and job dissatisfaction. 41 However, emotion-oriented approaches comprise multiple components (eg, validation and reminiscence), making it difficult to understand which one was the most effective. An additional RCT found that DCM positively affected DCWs’ stress and burnout. 38 A nonrandomized controlled study based on multisensory stimulation 39 showed immediate significant positive impacts on the 3 outcomes of interest. Finally, 1 of 2 behavioral-oriented approaches, which adopted a nonrandomized design, showed a reduced burnout in DCWs. 42 The remaining 2 studies reported no effects on staff’s psychological outcomes. 43,44 As a group, these studies provide valuable insights about the different types of PCC approaches that impact on DCWs. In line with previous literature, PCC can offer a better preparation for the challenging task of providing dementia care, enabling DCWs to respond to residents’ BPSD more effectively and with less personal impact on themselves. Such approaches are also more likely to reflect the type of care that DCWs would wish to provide, that is, care that is focused on the residents and on their needs, habits, interests, and wishes. 19,45

As identified in previous review, 20 this one demonstrates that studies in this area still lack sufficient rigor. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that implementing interventions within residential care facilities is hampered by several inherent methodological concerns.

Conducting RCTs to assess nonpharmacological interventions represents a challenge especially with respect to the blinding of participants. Yet, more could be done to blind outcomes assessors, something that was only noted in one of the included studies. 43 Better quality reporting of the method of allocation would also be a methodological advance.

The long-term effects of the interventions were only assessed in 2 studies, 38,41 and in the future follow-up data are required to demonstrate the extent to which the effects of interventions are maintained. This is particularly important, given that several previous studies have indicated that positive outcomes are not maintained over extended periods of time. 46 Another weakness concerns the possible existence of bias in samples. Only 1 study reported intention-to-treat analysis, 41 highlighting the necessity for future studies to undertake a “complete cases” analysis.

There was a great variability in the outcome measures used, further compromising comparability. Except for burnout, which was universally assessed with the MBI, stress and job satisfaction were measured using different tools. And even when the same tool was used, its application was inconstant across studies (ie, studies selected different subscales or items). Given the lack of widely accepted instruments to measure occupational stress and job satisfaction, future studies should use the most responsive and precise instruments relevant to their study aims and justify their use.

Finally, despite all approaches being focused on PCC, they have a different emphasis. For example, while some studies were focused on training staff to promote residents’ independence, 43 others were more focused on enhancing staff–resident communication. 39 This demonstrates the complexity of the term PCC and indicates that there is still a lack of conceptual clarity as to its meaning. In order to be able to compare the benefits of these different approaches, there is a need for further exploration of the concept and features of PCC.

Strengths and Limitations

A few limitations have to be considered within this review. Potential reporting bias may exist, as only studies published in scholarly peer-reviewed journals and in English language were included. There may have been other studies describing suitable interventions that were not included. Obtaining and including data from gray literature would probably reduce such bias. As well, the number of included studies could have been superior if other psychological variables were considered, namely self-efficacy or confidence. Moreover, the small number of studies and their methodological limitations reduce the inferences that can be legitimately drawn. Finally, post-only studies were eligible to be included in the review despite its recognized weaknesses.

Despite the limitations, this is the first review to date that focuses specifically on interventions addressing staff caring for people with dementia. This work is instructive and makes available important insights for the future development of this research area.

Conclusions

Based on the available evidence and considering the methodological weaknesses and heterogeneity of studies, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions about the efficacy of PCC approaches for DCWs. Yet, a tendency toward their effectiveness was apparent.

This review highlights the need for more well-designed research and higher quality reporting of study methodology. Specifically, reporting should include the method of randomization and treatment allocation concealment, information about blinding of participants, or outcome assessors and an intention-to-treat analysis should be performed. Future studies should carefully consider the use of more responsive and precise instruments relevant to their study aims and justify their use and follow-up assessments in order to determine any lasting effects. In order to compare the benefits of the different approaches, further exploration of the features of PCC is required.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT). AB received a scholarship [SFRHBD/72460/2010].

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Dementia: a public health priority. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ballard CG, Gauthier S, Cummings JL, et al. Management of agitation and aggression associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev. 2009;5(5):245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;287(16):2090–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miyamoto Y, Tachimori H, Ito H. Formal caregiver burden in dementia: impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and activities of daily living. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brodaty H, Draper B, Low BL. Nursing home staff attitudes towards residents with dementia strain and satisfaction with work. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(6):583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Magaziner J, German P, Zimmerman SI, et al. The prevalence of dementia in a statewide sample of new nursing home admissions aged 65 and older: diagnosis by expert panel. Epidemiology of dementia in nursing homes research group. Gerontologist. 2000;40(6):663–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matthews FE, Dening T. Prevalence of dementia in institutional care. Lancet. 2002;360(9328):225–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mongil R, Trigo JA, Sanz FJ, Gómez S, Colombo T. Prevalencia de demencia en pacientes institucionalizados: estudio RESYDEM. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2009;44(1):5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edvardsson D, Winblad B, Sandman P. Person-centred care of people with severe Alzheimer's disease: current status and ways forward. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rogers C. On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCormack B, McCance TV. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(5):472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kitwood T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First Buckingham. New york, NY: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woods RT. Discovering the person with Alzheimer's disease: cognitive, emotional and behavioural aspects. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5 suppl 1:S7–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fossey J. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7544):756–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sloane PD, Hoeffer B, Mitchell CM, et al. Effect of person-centered showering and the towel bath on bathing-associated aggression, agitation, and discomfort in nursing home residents with dementia: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1795–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chenoweth L, King MT, Jeon YH, et al. Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sidani S, Streiner D, Leclerc C. Evaluating the effectiveness of the abilities-focused approach to morning care of people with dementia. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(1):37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Edvardsson D, Fetherstonhaugh D, McAuliffe L, Nay R, Chenco C. Job satisfaction amongst aged care staff: exploring the influence of person-centered care provision. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(8):1205–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van den Pol- Grevelink A, Jukema JS, Smits CH. Person-centred care and job satisfaction of caregivers in nursing homes: a systematic review of the impact of different forms of person-centred care on various dimensions of job satisfaction. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(3):219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Evans S, Huxley P, Gately C, et al. Mental health, burnout and job satisfaction among mental health social workers in England and Wales. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gray Stanley JA, Muramatsu N. Work stress, burnout, and social and personal resources among direct care workers. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(3):1065–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brooker D. Dementia care mapping: a review of the research literature. Gerontologist. 2005;45(suppl 1):11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB. Historical and conceptual development of burnout. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional burnout:recent developments in theory and research. London: Taylor & Francis; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Spector PE. Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011].The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available at www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. UK: Lancaster University;2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bird M, Llewellyn Jones RH, Korten A. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a case-specific approach to challenging behaviour associated with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(1):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berkhout A, Boumans NPG, Nijhuis FJN, Van Breukelen GPJ, Huijer Abu-saad H. Effects of resident-oriented care on job characteristics of nursing caregivers. Work Stress. 2003;17(4):337–353. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davison TE, Hudgson C, McCabe MP, George K, Buchanan G. An individualized psychosocial approach for “treatment resistant” behavioral symptoms of dementia among aged care residents. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;19(5):859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGilton KS, O'Brien Pallas LL, Darlington G, Evans M, Wynn F, Pringle DM. Effects of a relationship-enhancing program of care on outcomes. J Nurs Scholarship. 2003;35(2):151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilson B, Swarbrick C, Pilling M, Keady J. The senses in practice: enhancing the quality of care for residents with dementia in care homes. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):77–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McKeown J, Clarke A, Ingleton C, Ryan T, Repper J. The use of life story work with people with dementia to enhance person-centred care. Int J Older People Nurs. 2010;5(2):148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoeffer B, Talerico KA, Rasin J, et al. Assisting cognitively impaired nursing home residents with bathing: effects of two bathing interventions on caregiving. Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):524–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Buron B. Life history collages: effects on nursing home staff caring for residents with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(12):38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCallion P, Toseland RW, Lacey D, Banks S. Educating nursing assistants to communicate more effectively with nursing home residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 1999;39(5):546–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jeon YH, Luscombe G, Chenoweth L, et al. Staff outcomes from the Caring for Aged Dementia Care REsident Study (CADRES): a cluster randomised trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(5):508–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van Weert JCM, van Dulmen AM, Spreeuwenberg PMM, Bensing JM, Ribbe MW. The effects of the implementation of snoezelen on the quality of working life in psychogeriatric care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005;17(3):407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Finnema E, Drões RM, Ettema T, et al. The effect of integrated emotion-oriented care versus usual care on elderly persons with dementia in the nursing home and on nursing assistants: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):330–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schrijnemaekers VJJ, van Rossum E, Candel MJJM, et al. Effects of emotion-oriented care on work-related outcomes of professional caregivers in homes for elderly persons. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 2003;58(1):S50–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Passalacqua SA, Harwood J. VIPS Communication Skills training for paraprofessional dementia caregivers: an intervention to increase person-centered dementia care. Clin Gerontologist. 2012;35(5):425–445. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wells D, Dawson P, Sidani S, Craig D, Pringle D. Effects of an abilities-focused program of morning care on residents who have dementia and on caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(4):442–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fritsch T, Kwak J, Grant S, Lang J, Montgomery RR, Basting AD. Impact of TimeSlips, a creative expression intervention program, on nursing home residents with dementia and their caregivers. Gerontologist. 2009;49(1):117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Reed PS, et al. Attitudes, stress, and satisfaction of staff who care for residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45 spec no 1(1):96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, Paton J, Lyketsos CG. Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psych. 2005;162(11):1996–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]