Abstract

Dementia caregivers often experience loss and grief related to general caregiver burden, physical, and mental health problems. Through qualitative content analysis, this study analyzed intervention strategies applied by therapists in a randomized-controlled trial in Germany to assist caregivers in managing losses and associated emotions. Sequences from 61 therapy sessions that included interventions targeting grief, loss, and change were transcribed and analyzed. A category system was developed deductively, and the intercoder reliability was satisfactory. The identified grief intervention strategies were recognition and acceptance of loss and change, addressing future losses, normalization of grief, and redefinition of the relationship. Therapists focused on identifying experienced losses, managing associated feelings, and fostering acceptance of these losses. A variety of cognitive–behavioral therapy–based techniques was applied with each strategy. The findings contribute to understanding how dementia caregivers can be supported in their experience of grief and facilitate the development of a manualized grief intervention.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, grief, cognitive behavioral therapy, telephone, caregiver support, qualitative content analysis

Introduction

An estimated 44.4 million people worldwide are currently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia, and this number is expected to increase to 75.6 million by 2030. 1 It is, however, not only those with dementia who should be of concern but also their caregivers. In addition to physical care, caregivers are confronted with changes in the behavior and personality of their family members. 2 Witnessing these changes can lead to experiences of loss and grief on a daily basis, with which many caregivers are unable to cope. In this article, we report the results of a qualitative content analysis examining how clinical psychologists in a telephone-based cognitive–behavioral intervention study responded to support caregivers in accepting and dealing with these changes.

Grief and Loss in Dementia Caregivers

Dementia caregivers are often heavily burdened. They show higher levels of stress and depression as well as lower levels of subjective well-being, physical health, and self-efficacy than noncaregivers and caregivers of patients with other diseases. 3 These differences are due to unique aspects of the dementia caregiving situation 3 as well as to the loss of the relationship with the care recipient. As attachment bonds are threatened and broken over the course of the disease, caregivers are confronted with a constantly changing situation. According to Bowlby’s theory of attachment, 4 breaking of attachment bonds can cause grief in the case of a meaningful relationship. This was demonstrated through an open-ended question included at the end of a quantitative study 5 : 253 caregivers, the majority of whom taking care for a family member in the moderate or severe stages of the disease at home, were asked whether they were grieving the loss of their loved one. Sixty-eight percent reported that they are currently grieving, and caregivers who did not report grief verbalized associated feelings.

The grief caregivers experience is similar to the grief after the death of a loved one 6 and has a multifaceted nature. 5,7,8 In contrast to the grief after bereavement, caregiver grief is prolonged and has no clear starting or ending point 5 as, in most cases, the disease progresses over 8 to 10 years. 9 Along with cognitive decline and loss of memory, the care recipients’ personality may change drastically, and they remain physically present but become psychologically absent, a phenomenon termed ambiguous loss. 10 Another critical component of the caregiver grief experience is anticipatory grief, 11 which includes grief over past, present, and future losses. Since the family member is still alive, caregivers often feel that their losses cannot be openly acknowledged and publicly mourned because these losses are not socially recognized or conflict with religious, family, or cultural values. 12 The resulting feelings of helplessness and isolation from the broader community have been described as disenfranchised grief. 13 Noyes et al 7 integrated the above-mentioned findings into the grief–stress model of caregiving. They propose that ambiguous loss is associated with the loss of companionship, communication, support, hope for improvement, and relationship dynamic change.

Caregivers are, however, often not aware of the grief inherent in dementia caregiving and confuse symptoms with symptoms of stress. 14 This phenomenon is referred to as masked grief 15 and because that grief is so often overlooked, it is one of the major risk factors for physical and mental health problems in dementia caregivers. Grief has been associated with caregiving burden, 16 the development of physical problems, 17 and depressive symptoms 18 and can be a barrier to the fulfilment of caregiving tasks. 19

Grief and Loss Interventions

While grief is a normal experience and psychotherapeutic interventions are not necessarily needed, 20 dementia caregivers constitute a high-risk group for the development of physical and mental health problems. Therefore, they can benefit from specialized interventions. Interventions can increase dementia caregivers’ ability to cope with the losses they have already experienced and prepare for the death of their care recipient. 21 To date, some recommendations have been made regarding grief interventions for dementia caregivers. 7,8,13 -16 Studies on existing interventions 12,21 mostly used group settings and focused on identifying and managing grief reactions. Kasl-Godley 21 reported a decline in depressive symptoms, and while participants in Sanders and Sharp’s 12 study showed an increase in grief from pre- to postintervention, they reported that the group was helpful because they learned about how grief influences health and well-being. An individualized approach was taken by the multicomponent grief intervention Easing the Way 22 that yielded a significant reduction in grief symptoms. However, these studies were pilot studies with small numbers of participants and did not incorporate control groups.

Acceptance of the reality of the loss and management of emotions were proposed as goals for grief counseling and therapy. 20 Studies that investigated interventions for problematic adaptions to loss have also found cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) to be effective, especially when dysfunctional thought patterns occurred. 23 Holland et al 24 investigated the effects a CBT-based intervention during caregiving had after bereavement and found improvement in normal and complicated grief symptoms. Emotional support, conveying information, and teaching cognitive skills were most effective for normal grief, while cognitive and behavioral strategies had the biggest impact on complicated grief. 24

Another focus for the design of interventions is that dementia caregivers are facing a difficult situation that cannot be changed per se. With emphasis on acceptance, mindfulness, and overcoming avoidance of experience, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, 25 a third-wave approach to CBT, also offers an appropriate framework.

Study Objectives

It was the objective of the present study to examine intervention strategies applied in a CBT-based trial to support grieving caregivers. Grief and loss have conclusively been shown to be part of the caregiving process, putting caregivers at risk of the development of physical and psychological problems both before and after the death of the care recipient. Consequently, dementia caregivers can benefit from psychotherapeutic interventions directly aimed at coping with losses and the resulting grief. There is, however, a need for studies that develop and subsequently evaluate such interventions, preferably with a cognitive–behavioral background. The present study aims to provide an understanding of the problems therapists explore and the intervention strategies they choose when grief and loss are expressed by caregivers in individual, CBT-based therapy.

Method

The study was conducted within a randomized controlled trial (RCT). 26 Using transcripts from therapy sessions, the present study qualitatively analyzed the therapeutic approach to grief, while the main RCT evaluated the effectiveness of a telephone-based, cognitive–behavioral intervention for dementia caregivers in Germany. The individual telephone-based setting seemed highly appropriate 27 because it allows caregivers flexible access to support without the problems they usually encounter in face-to-face or group settings (eg, logistic problems, time constraints, and care recipient cannot be left alone). Participants were recruited mainly via newspapers, cooperating institutions, and primary care physicians and were eligible for the study if they fulfilled the following criteria: full-time in-home caregiver of a person with a diagnosis of dementia and a score >3 on the Global Deterioration Scale, 28 no simultaneous psychotherapy, no cognitive impairment, and no acute mental or physical illness. Participants were allocated to 1 of the 3 study groups: intervention group, treated control group, or untreated control group. Caregivers in the intervention group received 7 manualized 50-minute therapy sessions over a period of 3 months. Six clinical psychologists trained in counseling and CBT delivered the intervention and received both preintervention training in application of the manual and regular supervision. While no therapist had a specific background in grief counseling, interventions for grieving caregivers were part of the training.

The manual was CBT-based and also included exercises on mindfulness and acceptance. It consisted of the modules improving problem solving and coping with challenging behavior, increasing pleasant activities, coping with stress and acute burden, identifying and modifying dysfunctional thoughts and core beliefs using cognitive techniques, psychoeducation, and, most important for the present study, accepting the disease and coping with change, loss, and grief. Therapists were free to differentially weigh modules according to the caregiver’s individual needs. All therapy sessions were audiotaped.

Qualitative content analysis, 29 a systematic theory- and rule-based analysis of communication, was chosen as the methodological framework for the present analysis. It permits to structure and differentiate between intervention strategies, which meet the study’s aims, since therapists’ responses to grief were expected to vary. Qualitative content analysis also relies on intercoder reliability, which ensures objectivity of the analysis.

Identification of the Material for Qualitative Data Analysis

The study sample consisted of 229 caregivers. For the present analysis, only sessions with caregivers in the intervention group (n = 129) were considered. Therapy sessions during which grief and loss were addressed were identified via a 2-tiered process: First, therapists’ session protocols and ratings 30 on a newly developed adherence scale, which included the application of interventions targeted at loss and change, and an adapted German version of the Cognitive Therapy Scale, which assesses therapeutic competences and the application of cognitive–behavioral techniques, were searched for interventions regarding grief, loss, and change. Second, 2 independent raters (the first and second authors) listened to all identified therapy sessions and selected sessions for analysis if their content reflected relationship losses (ie, relationship dynamic change, loss of companionship, communication, and support 7 ) and associated emotions. The agreement of the 2 raters was 95.6%, which was deemed satisfactory. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. The sequences from the selected sessions that contained the grief intervention were transcribed verbatim.

To determine that the identification procedure was valid and no relevant sessions were missed, the intervention group was divided into 3 subgroups: no focus on grief (caregivers with 0 sessions identified according to the procedure described above), minor focus on grief (1 or 2 sessions identified), and major focus on grief (3 or more sessions identified). Two caregivers were randomly selected from each group, and the audiotapes of all their therapy sessions that had not previously been identified as relevant for the study were screened for interventions regarding grief, loss, and change. Since the major focus on grief group only consisted of 4 caregivers, all of these caregivers were selected.

This screening did not yield any new grief intervention or counseling techniques, indicating that the identification procedure can be regarded as valid. Although grief was addressed in 1 session, this was in the context of a review of the previous session’s content. As grief interventions had previously taken place, grief and loss were also mentioned. This was, however, a repetition and was therefore not classified as a new intervention. In 3 other sessions, losses were briefly mentioned, but therapists instead focused on other therapy goals. This identification procedure therefore ensured that all material pertaining to grief interventions was analyzed.

Sample

Thirty-three caregivers (26.19% of the intervention group) received grief interventions and were included in the analysis. They were almost entirely female (90.9%, n = 30) and the sample included spouses (69.7%, n = 23) and adult children (30.3%, n = 10). The average age was 62.97 years (standard deviation [SD] = 10.46) with a range of 45 to 87 years. On average, participants had been providing caregiving duties for 4.6 years (SD = 3.09). Most care recipients were in the moderately severe (18.2%), severe (51.5%), or very severe (18.02%) stages of dementia.

Development of the Category System and Coding Procedure

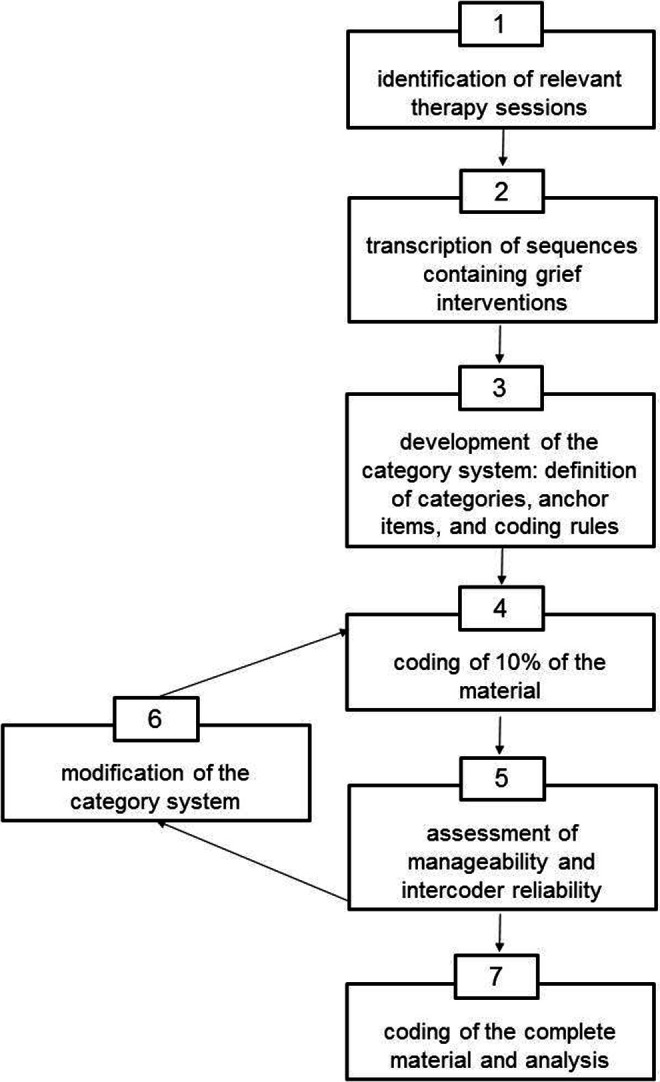

Qualitative content analysis is defined by a set of previously established steps (see Figure 1). 29 A category system that allows coding of grief intervention strategies was developed using a mostly deductive approach: Literature on grief interventions, for example, see Worden,20 and dementia caregiver grief 13 was reviewed, and intervention strategies recommended within this literature were defined as categories. Additional strategies were added from the transcripts using an inductive approach. Coding rules and anchor items (ie, good examples of the application of a strategy) were added to the category system.

Figure 1.

Flow Model of the Study.

Intercoder reliability was computed as a statistical measure of agreement between 2 independent coders. Krippendorff's α 31 was chosen because of its statistical superiority over other coefficients. Values over α = .80 indicate a reliable category system that allows for confident data interpretation, values between α = .68 and .80 allow only tentative conclusions, and values lower than α = .68 require a revision of the category system. As recommended, 29 10% of the material was randomly chosen for the first coding cycle and coded by 2 independent coders (the first and second authors) with experience in CBT for dementia caregivers to assess both the intercoder reliability and the manageability of the category system. The intercoder reliability (α = .74) was deemed too low. To improve reliability, all disagreements were discussed and revisions were made: 2 categories that overlapped were merged to create a new category, and the coding rules of all categories were improved to give more precise guidelines. In the second coding cycle, 10% of the material was again randomly selected and coded independently. In this second cycle, the intercoder reliability was found to be satisfactory (α = .80) for interpretation of the coded data.

The final category system consists of 4 categories that represent main grief intervention strategies and refer to different aspects of the grief experience: recognition and acceptance of loss and change, normalization of grief, redefinition of the relationship, and addressing future losses (see Table 1). In the coding process, the categories were assigned to the sequences of the therapy sessions that included grief interventions. Longer sequences were broken up into thematic units that were coded separately. Coding and analysis were conducted using ATLAS.ti software. 32

Table 1.

Category System of Grief Intervention Strategies.a

| Name of the Category | Definition | Anchor Item | Coding Rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| I: Recognition and Acceptance of Loss and Change | The therapist supports the caregiver in accepting losses associated with the disease and in accepting the new reality. The focus is also on the verbalization and disclosure of painful emotions associated with these losses, for example, see Worden 20 | “Because of this disease, he has changed so much; he is not the man you married, the man he used to be, anymore. In reality, you have already had to say goodbye to your husband, even though he is still alive.” | The therapist concretizes and explores what has changed due to the disease and which losses (primary or secondary) the caregiver has experienced. The therapist asks the caregiver to name and describe associated emotions from specific situations. Also focuses on feelings of guilt. |

| II: Normalization of Grief | Some caregivers assume that it is not right to grieve and therefore avoid it. Many also fear that grieving could lead to depression. The therapist communicates that it is normal and healthy to grieve and explains the difference between normal grief and depression. | “I think it is normal to be sad once in a while. I think it is quite important.” “Well, because … you worry you could become depressed if you allow yourself to grieve, be sad … ” | The therapist explains that grief is a normal reaction to a family member’s dementia that caregivers should allow themselves to grieve, and that grief does not cause mental health problems. Can also be directed at grief or expressions of grief (eg, crying) experienced during the therapy session. |

| III: Redefinition of the Relationship | As the disease progresses, the cognitive abilities and personality of the care recipient change. 7 This has strong implications for the relationship between caregiver and care recipient. The intervention is aimed at the recognition of these changes and the redefinition of the spousal or child identity. | “You are not husband and wife anymore. Maybe you are mother and child, but more likely caregiver and care recipient, right?” | The therapist explores the changes in the relationship between caregiver and care recipient or helps the caregiver to redefine the relationship with the care recipient. Also includes the adoption of roles and tasks the care recipient used to be responsible for. |

| IV: Addressing Future Losses | Dementia is a terminal disease. As the disease progresses, the caregiver anticipates further losses 11 and is confronted with decisions that could increase grief. | “You said, you hope you don’t have to go as far as putting your husband in a nursing home [ … ]. How do you cope with the fact that your husband is suffering from a terminal disease?” | The therapist focuses on anticipatory grief, painful future decisions associated with grief, and plans for the future, which can include the time after the care recipient has died. |

aThis is a shortened version of the category system, intended to give an overview. All examples were translated from German.

Results

The qualitative analysis was based on the selection of all therapist responses to grief. Sequences from 61 therapy sessions (ie, 9 hours and 44 minutes) were transcribed and sequences had a mean duration of 6 minutes (range = 30 seconds to 27 minutes). Grief interventions generally occurred early on in therapy, with over half occurring in the first (27.87%), second (16.39%), or fourth (18.03%) sessions of the therapy process. In most cases, either 1 (47.54%) or 2 (32.79%) sequences per session included grief interventions.

The analysis showed that therapists targeted recognizing and naming experienced losses, expressing associated feelings, and fostering acceptance of these losses. To achieve this, therapists most frequently used intervention strategies coded as recognition and acceptance of loss and change, followed by addressing future losses, normalization of grief, and redefinition of the relationship. Only in very rare cases (6 of the 61 sessions; 6.45%) did therapists apply strategies that could not be coded with the existing categories. These interventions generally pertained to caregiving losses (ie, personal freedom and social opportunities) rather than relationship losses. 7 Over the course of a session, therapists almost always used either 1 (62%; 38 sessions) or 2 (33%, 20 sessions) strategies; 3 strategies were used in only 5% of the sessions (3 sessions), and all 4 strategies were never used in a single session.

Recognition and Acceptance of Loss and Change

Recognition and acceptance of loss and change were used most frequently: it is made up 47.31% of grief interventions (in relation to the total of all applied intervention strategies) and was used in 44 of the 61 sessions (see Table 2 for examples). Within this category, therapists addressed the loss of spousal communication, intimacy, and rituals as well as the recognition that plans made for the time after retirement could no longer be fulfilled.

Table 2.

Examples for the Category Recognition and Acceptance of Loss and Change.

| Exploration of Losses | Classification of Changes as Part of Dementia | Addressing Unrealistic Hopes and Cognitive Restructuring | Identification of Painful Emotions | Psychoeducation on Loss as a Unique Aspect of Dementia Caregiving |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T: And now you are confronted with [the symptoms of dementia] directly, right? [ … ] With your husband changing, the isolation, and that your own life is not how you imagined it, right? C: Yes … we had this wonderful apartment by the beach in Mallorca and we had all these plans. [ … ] They will never come true now, right? | T: Because of this disease, he has changed so much; he is not the man you married, the man he used to be, anymore. In reality, you have already had to say goodbye to your husband, even though he is still alive. [ … ] C: Exactly! Now you’ve said the right thing. And I have not said goodbye yet. I have said goodbye to many things and it will go on, this goodbye. | T: Is it possible that behind the thought “The weather could have caused the forgetfulness,” there is hope that he might get better again? C: Yes! Don’t you think so? [ … ] T: I can understand this hope and, in fact, many spouses find it very difficult to accept the progressive nature of the disease. That’s something you don’t want and you always hope that it doesn’t progress further. And I can imagine that behind your thought that the weather could have caused his decline, there is hope that he’ll get better when the weather changes? C: Yes. It’s so hot at the moment and he doesn’t remember so many things. He hardly recognizes his son, he asks me ten times a day “Who is that?”. You don’t think that’s already…? T: It is possible. Maybe it’s the natural cause of the disease. [ … ] C: I’m glad you told me. I really hoped, if the weather got cooler, he would get better … | T: How do you feel when you realize there is something you always used to do [together] and all of a sudden it is not possible anymore? C: Well, I feel the loss and that makes me sad. | T: There is a difference between someone who has a partner, but that partner is not capable of being a real partner anymore, and someone who does not have a partner at all and who can get used to the situation. You are married, you have a partner. But still he cannot offer you what a healthy man could offer. C: Yes. T: And that is sad, that is what is sad about dementia. Sometimes, it is easier to accept it when somebody dies, but this disease is so difficult to bear because the person is still here but also gone. |

Abbreviations: T, therapist; C, caregiver.

With psychoeducation, therapists linked the care recipient’s behavior to the disease, thus framing the experienced losses as part of the disease. If caregivers held on to unrealistic hopes of finding some kind of treatment or discovering a reversible factor that had caused the symptoms (eg, weather conditions, see Table 2), therapists addressed and restructured these dysfunctional thoughts.

Caregivers experienced many painful emotions associated with these losses and changes, which they often had problems recognizing or understanding. Therapists guided caregivers to identify painful emotions, such as grief, anger, and guilt, and linked these emotions to previously identified losses. To validate the existence of negative emotions, therapists also emphasized what is special about caring for someone with dementia.

Addressing Future Losses

Therapists addressed future losses in 22.58% of their interventions and in 21 of the 61 sessions (see Table 3). When caregivers were confronted with the knowledge that the disease was terminal or that the final stage has been reached, thoughts of the care recipient’s death became inevitable and caregivers anticipated future losses. Therapists addressed the associated feelings and thoughts with a focus on reaching acceptance of the inevitable loss. Many caregivers avoided thinking about the future because it caused severe anxiety. Therapists then encouraged caregivers to prepare themselves and assisted in identifying resources that could help them cope in the future.

Table 3.

Examples for the Category Addressing Future Losses.

| Addressing Feelings and Thoughts Associated With Losses | Identification of Resources for Coping With Anticipated Losses |

|---|---|

| T: You are witnessing that his health is deteriorating and you lose him a little more each day. C: Yes, that exactly is my problem. T: How does that make you feel? P: Not so good, it makes me very sad. [ … ] I know it means I will be alone again. | T: Saying goodbye is a difficult topic that we don’t like to think about. But it could also be helpful to think about it before it is imminent, although you don’t know exactly what is coming, to think about what you would need for it to be a good goodbye. Something you would like to have done together or what you would like to have said. Just as a preparation to feel—I don’t know if you could call it that—“ready.” I think it is helpful to prepare for these difficult moments by thinking them through. |

Abbreviations: T, therapist; C, caregiver.

Normalization of Grief

Therapists focused on the normalization of grief in 13.98% of all grief interventions, addressing it in 13 of the 61 sessions (see Table 4). This intervention strategy was used when caregivers reported being sad or crying but forbidding themselves to admit to experiencing grief and sadness. Therapists first explained how they accept painful emotions and encouraged their expression during therapy sessions. They also used psychoeducation to clarify that grief is a normal reaction to the caregivers’ situation and validated the emotion and its expression. The therapists explained that it can be beneficial to acknowledge one’s grief, as avoiding it can have adverse effects on caregivers’ physical and mental health.

Table 4.

Examples for the Category Normalization of Grief.

| Expression of Acceptance of Negative Emotions | Framing Grief as a Normal Reaction, Validation of its Expression | Explanation of Adverse Effects of Avoidance | Restructuring of Unhelpful Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| T: It is okay to be sad one evening, to cry, and to say to yourself “I will function again tomorrow, but today I allow myself some moments of sadness.” That is, I think, absolutely okay. | T: This sadness you are feeling is absolutely normal and it is important to allow yourself to grieve. These negative emotions are absolutely normal; they are a kind of signal […]—they mean that you had a wonderful time with your husband and it is very important to give them space and to admit them for a moment, okay? C: Yes, I am admitting them. | T: It is very important that you give this sadness some space in your life. And I’d like to encourage you that it is absolutely okay to cry from time to time. It is healthy to allow ourselves to grieve rather than trying to avoid it. What do you think could happen if we tried avoiding it? C: I can imagine that we would explode one day. T: Yes, or we could become physically ill, or wouldn’t sleep well. We could also become depressed. | T: I think that was an important session today. C: Definitely, yes, definitely. Now that you’ve said that I can admit grief and not instantly become depressed, I think that I should admit it more. It doesn’t mean that I have to cry for hours, but just to say “It is not bad, it is what it is,” right? T: Exactly. And it actually is a normal reaction. I think—even if you cried for a few hours—it would be normal and it does not mean that you would become depressed. It is a normal, healthy reaction to the goodbye you are living through, right? It is difficult and you have a right to be sad. That’s not bad. |

Abbreviations: T, therapist; C, caregiver.

Some caregivers were afraid that being sad or crying would have negative consequences for their health that would, in the end, prevent them from taking care of their loved one; and they were also afraid that the sad feelings would never end. Therapists again used psychoeducation and cognitive restructuring to correct such assumptions.

As a balance to the expression of negative emotions, therapists also encouraged caregivers to engage in positive activities to take care of themselves when they were feeling sad.

Redefinition of the Relationship

Therapists focused on redefinition of the relationship in 9.68% of grief interventions and in 9 of the 61 sessions (see Table 5). It was clear from the caregivers’ statements during the therapy sessions that they were often not aware how their roles were changing over the course of caregiving. Role change centered on caregivers having to give up their roles as spouses or children and to instead identify as caregivers. Therapists explored how the roles have changed between a caregiver and care recipient and then focused on redefining this relationship.

Table 5.

Examples for the Category Redefinition of the Relationship.

| Exploration of Role Change | Redefinition |

|---|---|

| T: How would you define your current role? Does it still feel like a mother–daughter relationship? C: No, it’s not like that anymore, it’s the other way around. It’s more like me being the mother and my mother is like a child. The roles have changed. T: And what does that mean for your relationship? C: I can’t expect things from her anymore, I’m responsible now. I can’t rely on her advice anymore. | T: Anyway, your relationship has changed; it is not like it used to be. That is painful; you are not husband and wife anymore. Maybe you are caregiver and care recipient now, aren’t you? [ … ] C: Well, you know what I think sometimes? It would be better if I could define us as caregiver and patient. |

Abbreviations: T, therapist; C, caregiver.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to use a qualitative approach to analyze therapy sessions with dementia caregivers. Its results are based on the complete analysis of all sequences from therapy sessions drawn from a larger intervention study that were identified as relevant to the research question. Qualitative content analysis was a suitable method and, as indicated by the satisfactory intercoder reliability, the developed category system proved to be a reliable instrument for the qualitative assessment of therapists’ responses to grief.

The results illustrate which intervention strategies therapists could apply to respond to grief and contribute to our understanding of how dementia caregivers can be supported in their experience of loss to prevent further adverse impacts. The overarching intervention concept of the trial was CBT-based and therapists frequently used CBT techniques such as psychoeducation, restructuring of dysfunctional thoughts regarding grief, or engagement in positive activities to balance negative emotions. With each category representing a different aspect of the grief experience, the results support the conceptualization of dementia caregiver grief being multifaceted. 5,7,8

Within the category of recognition and acceptance of loss and change, therapists addressed the loss of companionship between caregivers and care recipients, their current life situations and shared plans for the future, and associated emotions. This category includes a variety of different intervention strategies that cannot be separated from each other, and it is their combination that enables therapists to guide caregivers toward an understanding and acceptance of the experienced losses. It became evident in many therapy sessions that caregivers had recognized these losses, but still found it difficult to see them as part of the disease, or to understand their own emotional reactions. Silverberg 14 has argued that many caregivers only recognize their grief after they are explicitly told that this is what is happening to them. Therapists in our study therefore either introduced grief themselves or guided caregivers to understand that this was the actual emotion they were experiencing. They addressed the emotions that caregivers felt in specific situations or toward the caregiving situation in general. These are important points to address in therapy. Doka 13 has pointed out that although the caregiver situation is a tremendous source of negative feelings, caregivers are often unable or unwilling to admit this, out of a desire not to burden the care recipient, a fear of social sanctions, or a simple lack of opportunities to disclose such emotions. To facilitate disclosure, the therapists educated caregivers about the nature of emotions to help them to understand why they felt certain ways. Although many of the study participants had been caregivers for years and had received information about dementia, many still had incorrect assumptions about what can cause changes in the care recipient’s behavior. It was therefore also part of the recognition and acceptance of loss and change to educate caregivers about the natural course of the disease. This information can be helpful for caregivers to let go of false hopes and to accept the changes as irreversible.

Addressing future losses focused on losses over the disease trajectory, including the death of the care recipient. Unlike the loss of shared plans between caregivers and care recipients, which was addressed under the category of recognition and acceptance of loss and change, intervention strategies in this category focused on losses that had not already occurred but that had to be expected because of the disease’s progressive nature. Many caregivers were reluctant to discuss the future, but therapists emphasized how important it was for them to prepare themselves for the death of their care recipients, rather than to avoid thinking about it. The importance of this preparation was clearly illustrated in a study by Hebert et al, 33 which assessed the extent to which 222 bereaved dementia caregivers had been prepared for the death of their care recipients. Results showed that unprepared caregivers experienced more complicated grief, depression, and anxiety.

When therapists focused on normalization of grief, caregivers learned that grief is a normal aspect of caregiving and that acknowledging it does not have negative consequences but might even prevent further physical and mental health problems. Dementia caregivers are often afraid of being overwhelmed by painful emotions, are unsure of how to manage these emotions, 5 or experience disenfranchised grief. 13 For caregivers in our sample, it was more often the case that they themselves did not seem to allow and/or accept their grief, indicating feelings of self-disenfranchisement. 12,15 Many believed that admitting their grief would be wrong or unfair to care recipients or were afraid of negative consequences for their mental health if they were to admit their grief. In this case, therapists again restructured such thoughts and provided information about the nature of grief, which helped caregivers to accept the existence of negative emotions. As Spira et al 34 found caregiver avoidance of negative feelings to be associated with increased depressive feelings, helping caregivers to accept the existence of negative emotions was a key strategy.

When focusing on redefinition of the relationship, the therapists supported the caregivers in understanding that their spousal or parent–child relationships were lost. Most caregivers had already perceived changes in their roles, as their loved ones had gradually changed from equal spouses or parents into more child-like persons. Addressing this experience during therapy was still painful but the therapists encouraged the caregivers to define their new roles, which were mostly those of caregivers or parents. In our extensive experience with CBT for dementia caregivers, these types of roles help to fulfill daily caregiving tasks and accept outside help. Therapists did, however, not aim at emotionally disengaging the caregiver from the care recipient. On the contrary, we believe that supporting caregivers to abandon emotional avoidance and accept the occurring role change leads to a more empathic and adequate behavior toward the care recipient. The design of the study did not allow testing this hypothesis, but changes in caregiver behavior and the intervention’s impact on the care recipients need to be evaluated in the future.

Implications for Caregiver Interventions

According to the caregivers’ self-report within the process evaluation 26 conducted to gain insight into the treatment implementation, grief interventions helped them to accept losses and facilitated emotional processing. The final aim of interventions in all categories was acceptance of loss and change and overcoming avoidance of associated painful emotions. As this is in line with the goals of ACT, it can be concluded that third-wave approaches to CBT are suitable for grieving caregivers. By focusing on acceptance of the new reality, the therapists also chose an approach that is among the main aspects of grief counseling and therapy after bereavement. 20 The categories were partly based on strategies recommended by Doka 13 and Worden 20 and then adapted to account for the special situation of grieving caregivers. The good reflection of the material by the category system highlights that the established grief intervention strategies are suitable for dementia caregivers but also brings to our attention what special aspects therapists need to focus on when working with this group.

Based on these results, we developed a grief intervention module that has been included in a CBT manual for dementia caregivers. 35 The module is being applied by therapists in an ongoing RCT with dementia caregivers, and analyses of its applicability and effectiveness are currently conducted.

In accordance with previous research in this area, 14,15 the present study highlights how difficult it is for dementia caregivers to recognize and talk about their grief. It is important for therapists who work with dementia caregivers to keep this difficulty in mind and to ask about experiences of grief and loss openly; however, therapists must of course make decisions regarding the appropriate interventions on a case-by-case basis, for example, while some caregivers can benefit from overcoming their avoidance of grief, avoidance can also serve a protective function that helps caregivers to cope with their daily tasks. More research is needed to better understand how therapists can recognize grief, as well as when and if the expression of grief should be encouraged during the therapy process.

Limitations

Although the present analysis provides valuable insights into grief interventions, it has several notable limitations. The first is that only the sequences that included intervention strategies explicitly directed at grief and loss were transcribed, other techniques that therapists used that may have been indirectly connected to grief were not included. To address this limitation, transcriptions of the complete therapy sessions are provided in an ongoing qualitative study.

Second, sessions from only 26.19% of the sample were included in the analysis, leaving information regarding how other participants coped with their experienced losses unknown. We know from other studies, for example, see Sanders and Corley’s study,5 that most caregivers suffer from grief, which is often not addressed directly but is instead expressed indirectly through vague negative emotions or physical symptoms. Caregivers within the larger sample may not have received the grief interventions under study because they avoided bringing up losses in their sessions. Conversely, it is also possible that these caregivers had already found ways to cope with their grief or that they did not experience their losses as significant or as causing grief; in either case, these caregivers would not need therapist support. However, more research is needed to understand these individual caregiver experiences and to better differentiate between when caregivers are avoiding grief and when they are genuinely not experiencing it.

Due to the telephone-based setting, it is also possible that certain nuances pointing to indirect or masked grief were not noticed. Caregivers, however, expressed a high satisfaction with the telephone-based setting 26 and in an ongoing study(36), the satisfaction of participants in a face-to-face setting was equally high to that in the telephone-based condition.

Despite these limitations, this study answers the call for grief intervention guidelines specifically tailored to the unique needs of dementia caregivers. The resulting set of intervention strategies was derived directly from therapy sessions and we anticipate that these strategies can therefore be successfully integrated into other therapy settings.

Footnotes

This article was accepted under the editorship of the former Editor-in-Chief, Carol F. Lippa.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this study was provided by Bundesministerium für Gesundheit [German Federal Ministry of Health], “Leuchtturmprojekt Demenz” [LTDEMENZ-44-092].

References

- 1. Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia statistics. 2014; Web site. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics. Accessed March 6, 2014.

- 2. Perren S, Schmid R, Wettstein A. Caregivers’ adaptation to change: The impact of increasing impairment of persons suffering from dementia on their caregivers’ subjective well-being. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(5):539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Volument II Separation, Anxiety and Anger. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanders S, Corley CS. Are they grieving? A qualitative analysis examining grief in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Work Health Care. 2003;37(3):35–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meuser MT, Marwit SJ, Sanders S. Assessing grief in family caregivers. In: Doka KJ, ed. Alzheimer’s Disease: Living With Grief. Washington, DC: Hospice Foundation of America; 2004:169–195. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Noyes BB, Hill RD, Hicken BL, et al. Review: The role of grief in dementia caregiving. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(1):9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanders S, Ott C, Kelber S, Noonan P. The experience of high levels of grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Death Stud. 2008;32(6):495–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(2):131–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boss P. Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rando T, ed. Loss and Anticipatory Grief. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sanders S, Sharp A. The utilization of a psychoeducational group approach for addressing issues of grief and loss in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Soc Work Long Term Care. 2004;3(2):71–89. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doka KJ. Grief and dementia. In: Doka KJ, ed. Alzheimer’s Disease: Living with Grief. Washington, DC: Hospice Foundation of America; 2004:139–155. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Silverberg E. Introducing the 3-A grief intervention model for dementia caregivers: acknowledge, assess and assist. Omega-J Death Dying. 2007;54(3):215–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dempsey M, Baago S. Latent grief: The unique and hidden grief of carers of loved ones with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1998;13(2):84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holley CK, Mast BT. The impact of anticipatory grief on caregiver burden in dementia caregivers. Gerontologist. 2009;49(3):388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1960–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanders S, Adams KB. Grief reactions and depression in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease: results from a pilot study in an urban setting. Health Soc Work. 2005;30(4):287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frank JB. Evidence for grief as the major barrier faced by Alzheimer caregivers: A qualitative analysis. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;22(6):516–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Worden JW. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kasl-Godley J. Anticipatory grief and loss: implications for intervention. In: Coon DW, Gallagher-Thompson D, Thompson LW, eds. Innovative Interventions to Reduce Dementia Caregiver Distress. New York, NY: Springer; 2003:210–219. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ott CH, Kelber ST, Blaylock M. “Easing the way” for spouse caregivers of individuals with dementia: a pilot feasibility study of a grief intervention. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010;3(2):89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boelen PA, de Keijser J, van den Hout MA, van den Bout J. Treatment of complicated grief: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(2):277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holland JM, Currier JM, Gallagher-Thompson D. Outcomes from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) program for bereaved caregivers. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(1):190–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilz G, Schinköthe D, Soellner R. Goal attainment and treatment compliance in a cognitive-behavioral telephone intervention for family caregivers of persons with dementia. GeroPsych. 2011;24(3):115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tremont G, Davis JD, Bishop DS, Fortinsky RH. Telephone-delivered psychosocial intervention reduces burden in dementia caregivers. Dementia. 2008;7(4):503–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. In: Flick U, von Kardorf E, Steinke I, eds. A Companion to Qualitative Research. London, Great Britain: Sage; 2004:266–269. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schinköthe D, Wilz G. The assessment of treatment integrity in a cognitive behavioral telephone intervention study with dementia caregivers. Clin Gerontol. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hayes AF, Krippendorff K. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. CMM. 2007;1(1):77–89. [Google Scholar]

- 32. ATLAS.ti [computer program]. Version 6.2. Berlin, Germany: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hebert RS, Dang Q, Schulz R. Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: Findings from the REACH study. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Spira A, Beaudreau S, Jimenez D, et al. Experiential avoidance, acceptance, and depression in dementia family caregivers. Clin Gerontol. 2007;30(4):55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilz G, Schinköthe D, Kalytta T. Therapeutische Unterstützung für pflegende Angehörige für Menschen mit Demenz. Das Tele.TAnDem Behandlungskonzept [Therapist Support for Dementia Caregivers: The Tele.TAnDem Intervention Program]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe; 2015. [Google Scholar]