Abstract

This literature review focused on the experience, care, and service requirements of people with younger onset dementia. Systematic searches of 10 relevant bibliographic databases and a rigorous examination of the literature from nonacademic sources were undertaken. Searches identified 304 articles assessed for relevance and level of evidence, of which 74% were academic literature. The review identified the need for (1) more timely and accurate diagnosis and increased support immediately following diagnosis; (2) more individually tailored services addressing life cycle issues; (3) examination of the service needs of those living alone; (4) more systematic evaluation of services and programs; (5) further examination of service utilization, costs of illness, and cost effectiveness; and (6) current Australian clinical surveys to estimate prevalence, incidence, and survival rates. Although previous research has identified important service issues, there is a need for further studies with stronger research designs and consideration of the control of potentially confounding factors.

Keywords: younger onset dementia, care and service requirements, experience of younger onset dementia, epidemiological estimates

Introduction

The provision of evidence to underpin decisions on services and supports for people with younger onset dementia (YOD) or early-onset dementia (EOD) is an emerging field. There is an increasing recognition of the different etiologies, trajectories, and implications of the diagnosis of dementia for people who are aged younger than 65 years at onset.

Although there is some debate over which terminology should be preferred, 1 we refer to YOD throughout as this term is commonly used in Australia, and the articles reviewed used the terms YOD and EOD interchangeably. Younger onset dementia reviews have predominantly focused on Alzheimer’s disease or frontotemporal dementia (FTD). 2 Consequently, the definition of the term “younger onset dementia” was broad 1 and encompassed major forms of dementia that occurred in those younger than 65 years. It included people with early-onset Alzheimer disease (EOAD), vascular dementia (VaD), FTD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and dementia associated with other conditions such as Huntington’s disease, Down’s syndrome, HIV/AIDS dementia, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and alcohol-related dementia (ARD).

This rapid 3 literature review, encompassing a broad overview of YOD, was commissioned by an Australian Government agency to inform future service development. The review examined the literature relating to the epidemiological aspects of YOD, the issues faced by people with YOD and their families, their needs and care requirements, and current programs and service initiatives. Our aim was to establish key aspects for the design and delivery of effective services and programs to meet the needs of people with YOD which have been identified in the international literature.

The review considered social, economic, and environmental factors that enable and support people with YOD, drawing on information available within the community, disability, and health care sectors. The review examined psychosocial program and support interventions but did not include an evaluation of medical and pharmacological therapies.

Methods

The literature search included peer-reviewed international academic literature and “gray literature” (such as reports by government agencies, leading community advocacy and education organizations, service providers, and other Web-based information).

Academic Literature

Relevant bibliographic databases were searched including MEDLINE, CINAHL, Academic Search Complete, Psychological & Behavioral Science collection, Scopus, ProQuest Central, Informa Healthcare, Cochrane Collaboration, and Biomed Central. The search was limited to articles in English from the year 2000 to current as recent research was the focus of the review. However, where information from earlier literature was identified as relevant, this was included.

The following search terms were included:

(“young onset” or “early onset”) AND dementia AND NOT “elderly” or “older”;

“Alzheimer’s” or “vascular dementia” or “frontotemporal dementia” or “Huntington’s disease” or “HIV” or “AIDS” or “acquired brain injury” or “Parkinson’s disease” or “Lewy bodies” and “cognitive impairment” or “neurocognitive disorder”;

“community support” or “community care programs/interventions” or “community services” or “community participation” or “service needs” or “employment participation” AND NOT “clinical”; and

“special needs” or “Indigenous or Aboriginal” or “LGBTI” or “homosexual” or “lesbian” or “rural” or “lifestyle” or “living alone” or “homeless.”

Term groups were then combined using AND in the following manner: 1 AND 2 AND 3; 1 AND 3 AND 4; 1 AND 2 AND 4.

Nonacademic Gray Literature

The nonacademic literature search used terms similar to the academic literature search, which included the following components:

surface Web (eg, Google);

country searches (eg, health and community service departments and community advocacy organizations);

dementia-specific site searches; and

other areas such as international conferences and professional associations.

Protocol-driven search strategies 4 were supplemented with “snowballing” methods such as reference list and citation searches, author searches, and hand searching of key journals.

Procedures for Study Selection and Review

Criteria for inclusion of academic and nonacademic articles were (1) a primary or comparative focus on YOD and (2) relevance to the service needs and service provision for people with YOD. Abstracts were retrieved, examined, and reviewed for their relevance based on the inclusion criteria by 2 researchers. Where disagreement occurred, these abstracts were checked by a third researcher and consensus concerning article retrieval was reached. Full texts of articles retrieved were then rated concerning their strength of evidence (see Appendix A). Given the emerging nature of evidence in this research field, qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods articles were included, but the discussion was guided by their level of evidence.

Following a thematic analysis of the studies, they were grouped into the following areas:

epidemiological studies concerning prevalence, incidence, and survival;

experiences of people with YOD, their carers, and families;

special needs groups;

particular programs (nonpharmacological program evaluations); and

service utilization and service design and development.

Review and summary tables were developed and included details such as the author and date, location, topic, research design, strength of evidence, study numbers, and focus.

Results

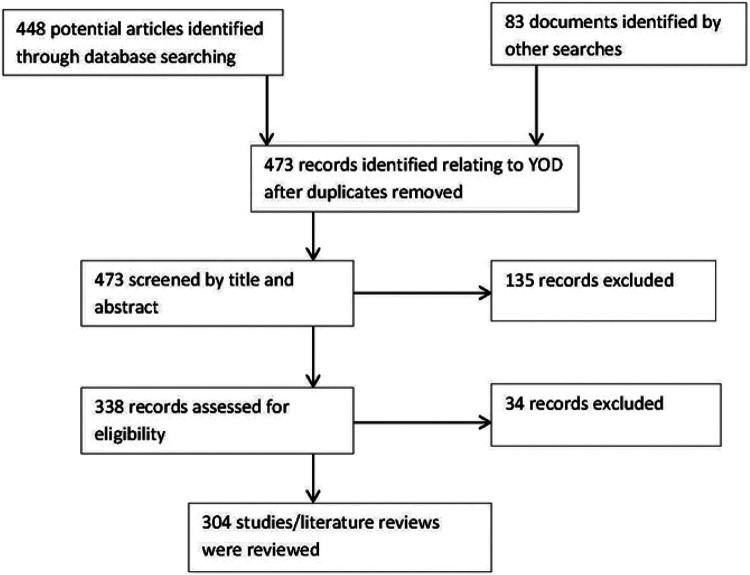

The search identified 448 documents of which 304 were included in the review. There were 221 (73%) academic articles and 83 (27%) documents included from the gray literature. Literature was sourced from a range of countries including Australia (31%) and international literature (69%) with those contributions mainly being from the United Kingdom and Europe, the United States, and Canada. Overall, 53% of the articles cited here were classified as acceptable practice or better, 43% were rated as emerging practice or less, and 4% of the articles were considered as not applicable for rating (eg, policy statements). These proportions reflect the emerging nature of evidence in this field. Figure 1 provides an outline the study selection process. The results are described subsequently in relation to the content areas identified.

Figure 1.

Younger onset dementia (YOD) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart of study selection.

Epidemiological Studies Concerning Prevalence, Incidence, and Survival

These studies are important as they provide an estimate of the magnitude of these issues and are useful for service planning purposes. The review considered 21 articles of which 52% primarily presented Australian data 5 -16 and 44.5% international data. 17 -26 Most (86%) of these articles were considered to have an acceptable strength of evidence (see Appendix A).

However, most Australian and international estimates of prevalence were based on pooled data arising from meta-analyses of Western European and Northern American studies conducted in the 1990s. 5 -7,10,17,18,22,25 Many of these studies used different methods and had small samples and relatively few studies pertained to Australasia. 25 The accuracy of these estimates is debatable, given the international differences that have been reported. 19 Awareness of YOD may have changed in recent years, with improvements in neuroimaging technology and diagnostic procedures that may influence the identification of cases with dementia. 27 -29

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report 7 used United Kingdom estimates 17,18 for the under-60 age-group but data from a more recent meta-analysis 25 for the other age-groups. The AIHW 7 estimated that there were 23 900 Australians, younger than 65 years, with YOD in 2011. Studies by Access Economics 5,10 used United Kingdom figures 17,18 for the under-65 age-group and estimated that for 2011, there were 16 239 cases of YOD. 10 The differences in figures to those provided by AIHW 7 may be due to differences in calculating the rate for the 60 to 64 years age-group among other methodological differences. The AIHW 7 estimated that YOD represents about 8% of all dementias compared with the Access Economics estimate of 6.1%. 10

Limited data were found 12,13,30 concerning the prevalence and incidence of YOD in Australian Indigenous communities. Some of these studies did not have a particular focus on YOD or did not include persons younger than 60 years, but these suggested that the prevalence of dementia may be much higher than previously estimated.

Given the above-mentioned data, more accurate and current Australian research concerning prevalence, incidence, and survival is required, as these estimates may have major implications for service utilization and planning.

Prevalence studies vary considerably in their estimates of YOD diagnoses. In a United Kingdom 17,18 study undertaken in the 1990s, the major types of YOD were EOAD (34%), VaD (18%), FTD (12%), ARD (10%), DLB (7%), and other dementias (19%). A recent systematic review 26 identified considerable variation in the proportions of the various subtypes of YOD reported across studies. A recent Australian catchment study 15,16 reported a higher proportion of ARD.

A large French memory cohort study reported lower rates for EOAD (22%) compared with the later onset dementia (LOD) group, and FTD, ARD, TBI, and Huntington’s disease were more frequent EOD diagnoses. 24 Some studies have reported a slightly greater proportion of males (52%-58%) for the YOD groups, whereas women may be overrepresented in the LOD groups. 18,24

Some types of YOD such as ARD are potentially more preventable, and recent findings have indicated that potent combination of antiretroviral treatments for HIV/AIDS appear to reducing the incidence of this form of YOD. 31,32 This suggests that new treatments or health promotion interventions may have the potential to affect both the incidence and the prevalence of YOD and therefore future projections. 11

Evidence on the impact of dementia on survival is mixed with the average survival time from symptom onset appearing to be 7 to 9 years, but it may range from 3 to 10 years due to differences in diagnostic criteria, definition of onset, individual characteristics (eg, age, sex, and comorbidities), and the type and severity of dementia. 8 People with YOD may be more physically fit at the time of their diagnosis with less comorbidity. Estimated average survival ranged from 7.6 to 9.6 years from onset of symptoms 20,23 and 6.08 years from diagnosis. 20

The Experience of YOD

Overall, 44% of the literature for this section was rated as emerging practice or less and 75% of this literature was from international sources. Younger onset dementia commonly occurs in people aged between 40 and 65 years. This earlier onset raised a number of issues including loss or diminishment in roles such as provider, parent, and spouse and the significant adjustment to those changes that is required. Associated with the common loss of employment, people with YOD and their families experienced problems concerning loss of income and financial problems, 1,33,34 exacerbating an already difficult situation.

A major constraint facing people with YOD was in obtaining a timely and accurate diagnosis. Symptom overlap across YOD subtypes made differential diagnosis complex and difficult. 2,33 Standardized measures used to assess cognitive status were usually not those most sensitive to dementia status. 35 Problems experienced by people with YOD in obtaining a diagnosis (eg, time delays, initial misdiagnosis, or misrecognition of symptoms) were commonly reported in the research literature. 2,33,36 -41 A recent study indicated that the time to diagnosis for YOD from the onset of symptoms was on average 4.4 years compared to 2.8 years for LOD. 42

Evidence regarding the presence of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) was equivocal, with some studies reporting a higher presence for some subtypes such as FTD. 27,43 -48 However, BPSD were relatively common for most types adding to the needs and care requirements for people with YOD. 17,42 The most common BPSD for the EOAD group was apathy, 42 whereas aggression and disinhibition were more commonly reported for FTD. 27,43,44

Some types of YOD such as Huntington’s disease carry a high level of genetic transmission; Down syndrome carries a high risk for the development of dementia, and some forms of AD are more strongly associated with genetic risk factors. 49 For such affected groups, genetic counseling will be of prime importance.

Many of these issues were identified in the research literature that examined the experience of YOD from the perspectives of people with YOD, their partners, children and carers.

Some studies 50 -62 have interviewed people with YOD about their personal experience. Most could be characterized as qualitative thematic analyses of interviews based on small sample sizes of 20 persons or less. 52,54 -56,58,59 The common issues reported were the emotional shock of diagnosis, problems with obtaining a diagnosis, adjusting to the diagnosis and feeling stigmatized because of the dementia “label,” lack of referrals to support services, falling between the cracks of service systems, a lack of access to age-appropriate services and programs, and financial problems. Personal challenges identified included loss of independence, loss of employment, loss of empowerment, role changes, and the rebuilding and restructuring one’s life. Loss of empowerment was associated with the feeling that involvement in decision making was being denied often by well-meaning carers or service staff. There was a strong desire expressed by many to remain engaged and in control of their lives as best they could. 62

Spousal and family carers reported similar issues concerning services. Early recognition and referral was seen as a major area for service improvement by both people with YOD (94%) and carers (69%). 63

Other carer issues included managing BPSD, grief associated with the “loss” of spouse (the person as they were prior to dementia), juggling the caring role with other daily life responsibilities including employment, parenting, and difficulties in making plans for the future. 64 -75

Earlier diagnosis was seen as important as spouses reported that prior to diagnosis, they may have made mistaken attributions concerning their partner’s symptoms which may have negatively affected their marital relationship. 74 Many spouses experienced social isolation 76 -78 and found it difficult to balance addressing their own needs with their caring role.

Relatively few studies interviewed children of people with YOD, and the sample sizes generally included less than 15 children. 79 -85 This literature 78 -86 mentioned perceived stigma and associated shame/embarrassment, bewilderment, family conflict, high care burden, the physical challenge of caring, psychological issues, and problems at school. Many children reported undertaking a demanding caring role while facing the developmental challenges of growing up.

Coping strategies, family cohesion, and security of attachment were raised as issues. Some children reported positive effects of their caring role 83 such as maturation and the experience gained. However, these children have substantial needs for support, 87 and due to the care burden placed upon them, they may have a potential for psychological and social disadvantage 88,89 which needs further exploration. 90

Some studies used more quantitative approaches and standardized scales to assess carer burden, stress, unmet needs, the presence of psychiatric symptoms among carers, and health-related quality of life and well-being. These studies indicated high levels of stress and burden for carers, poorer quality of life, and unmet needs including social isolation, depression, and anxiety. 48,68,91 -94

Some studies used patient carer dyads to explore these themes, 33,48,73,95 allowing patient data (eg, severity, BPSD, etc) to be directly related to carer findings, thereby providing a somewhat higher level of evidence. Some studies compared YOD and LOD groups, 47,75,96 but some studies had poor control of potentially confounding factors (eg, the duration of the caring period, age, and diagnostic composition of the comparator groups). 73,84 Although more recent studies from the Netherlands 33 have addressed the course of illness, there is a requirement for further longitudinal research.

No studies were found that focused on the experience of people with YOD living alone or those who had no familial carer. There was little exploration of the experience of parental carers for people with YOD. It has been estimated that for dementia, overall approximately one-third of people with dementia live alone. 97 However, there were little data available concerning the YOD subgroup, which may be likely to have high service needs. 23,92 Premature placement in residential care facilities may be an issue for this group which requires exploration.

Studies focused on service experience issues 21,33,36,88,98 -103 noted the lack of a clear diagnostic pathway, poor provision of information, the lack of appropriate referrals to support services, and the high volume of informal care provided. High levels of unmet needs for people with YOD in such areas as daytime activities, communication, social companionship, intimate relations, and information were reported, 104 and these were significantly associated with the level and presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

These factors might suggest the earlier use of community support services may have the potential to delay institutionalization. 21,105 Despite the endeavors of major advocacy organizations for dementia to provide comprehensive information, the need for clear information and advice is still a major unmet need for carers and patients. It would be desirable if people with YOD and their families were routinely provided with clear written information at the point of diagnosis, 103 and consideration could be given to a telephone enquiry support service. 106

Special Needs Groups

Integral to inclusive service planning, development and delivery for any population are considerations of any special needs which people may have with regard to service access and equity, in addition to the primary diagnosis of YOD. Legislation regarding this issue varies internationally, but, for example, Australian Commonwealth legislation 107 recognizes a range of people as having special needs with regard to access and equity, including people from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, non-English speaking backgrounds, and those residing in rural and remote areas. It also includes people who are financially or socially disadvantaged, veterans, homeless or at risk of becoming homeless, care leavers (people who had been raised in care homes), or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and people.

There were relatively few articles (19) that addressed these issues directly, of which only 3 articles discussed issues specific to YOD rather than to dementia overall, and 47% were classified as representing “emerging practice” or lesser levels of evidence (see Appendix A). The majority (74%) of this literature was Australian, but although the cultural mix varies across countries that make direct comparisons difficult, 108 the broad themes that emerged are likely to be relevant in other countries.

The key messages for these groups was to ensure the cultural, linguistic, and geographic factors were adequately identified and addressed in the planning, funding, and delivery of services. Importantly, there are people living with YOD who may be classified under multiple special needs groups and therefore may experience disadvantage on several fronts. 41

Barriers identified included:

lack of access to culturally appropriate diagnostic services 41,108 -114 and the need for the use of culturally appropriate assessment tools 13,30,35,115 ;

denial of dementia within some cultural groups 105,108,110 ;

lack of linguistically and culturally appropriate services and appropriately trained staff 41,109,110,113 ;

lack of available information about existing services 41,110,116,117 ;

service access and transport availability issues – especially in rural and remote areas. 41,109,110,113

Living in a rural or remote region is likely to be disadvantageous because mainstream services may be scarce or nonexistent, restricting both choice and access. Given the rarity of YOD, it is highly unlikely that appropriate services for this group with special needs would be available, particularly in rural and remote areas. 41,64,110

The literature emphasized that the needs of these groups are complex, multifaceted, and dynamic and become more so with the onset of dementia, reinforcing the call for person-centered, culturally appropriate, flexible service options.

Particular Programs

A range of community-based programs and nonpharmacological interventions were identified for people with YOD, their carers, and families; however, the majority of the literature provided limited evidence concerning program effectiveness, and therefore, 50% of these articles were rated as “emerging evidence.” Recent initiatives such as INTERvention in DEMentia (INTERDEM), an interdisciplinary European collaborative research network on early and timely interventions in dementia, are endeavoring to improve the quality of research concerning the assessment of psychosocial interventions for dementia more generally. 120

Tailored physical activity programs, 121 -125 cognitive stimulation (eg, reminiscence therapy), 121,122,126 -129 and cognitive rehabilitation programs (using strengths to compensate for impairments) 120 have been shown to have positive outcomes on cognition. Support programs, particularly those that include both the person with dementia and the carer, were also helpful with promising results identified for memory loss programs/support groups. 130 -135

Facilitation of support groups through communication technology, such as e-mail and videoconferencing, showed some promise for carers. 78,136 -138 Although people with cognitive deficits often have difficulty with everyday technology, 139 some assistive technology programs (eg, to assist with television and telephone management) were found useful 140 -142 by people with YOD.

Programs that provide active meaningful participation, 114,122,143,144 horticulture, 145 -147 volunteering, 148 -150 supported workplaces, 151,152 and creative expression programs 153 warrant further study to clarify the design and delivery attributes that are most effective for people with YOD. Recent evidence on supported workplaces for people with dementia indicated positive impacts on self-esteem and life satisfaction and when combined with reflective therapies helped to bring about action and change within the individual. 151,152 Social groups can fill an important gap in services, providing semi-independent activity as well respite for carers. 154,155

Programs that provide individually tailored support 49,105 to people with YOD and their carers, such as case management or a key worker and carer training, 2,49,122,156 -158 warranted further research as did a self-management model for people with YOD. 159 It was also found that relatively few studies examined the cost-effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for dementia overall, and the application of these findings for the YOD group needs further assessment. 21,160

Given the limitations of the evidence underpinning programs, a culture of outcome evaluation should be developed. This should include the use of standardized outcome measures as well as qualitative approaches to evaluate effectiveness.

Service Utilization and Service Design and Development

As for dementia overall, few studies addressed the issues of service utilization and the costs of illness for the YOD group 17,161 or included consideration of social and informal care costs. 23,162 Studies indicated the period from the onset of symptoms to permanent residential care placement for people with YOD was quite long (eg, 6-9 years), and the level of informal care provided was high, placing a significant burden on these families. 23,162 Although some studies indicated a relatively high use of institutional services (eg, hospital admissions, nursing home respite, etc), 17,21,43 others reported that community service use was relatively low for this group. 23,34,43,99,100,162 This may reflect the absence of appropriate referrals to relevant support services but may also relate to attitudinal barriers or a lack of awareness about how these services might assist them. 98,163,164

Due to the earlier age of onset, service needs for those with YOD differ from those with LOD as many people with YOD could still be rearing children and may still be supporting a family financially. 1 Existing services for other disease groups, or for older people with dementia, may not have the flexibility and applicability required to respond to the broad range of needs a person with YOD and their family may require from a service. 17,62,88,161 For example, staff of dementia services for older people may not be skilled in providing referral support regarding the financial and employment issues that may arise when a person with YOD may feel pressured into taking early retirement. 60,165 Younger onset dementia service workers need to be able to work across sectors and link the person with YOD to services such as income support as well as helping them negotiate other services that may be required.

Suggested service improvements included the need for a central contact point for services or the adoption of case management and key worker approaches 2,33,105 that could provide individually tailored, person-centered services and for existing services to provide programs/services that are more age appropriate for people with YOD. 50,161,166,167

The examination of the literature by Koopmans et al 1 regarding YOD services and good practice models revealed that most evidence for good practice is not based on empirical studies, rather it is mostly the expert opinion of health professionals working with people having YOD or more recently from consumers. Our analysis also indicated that 44% of this literature was rated at the level of emerging practice or less.

Key themes from the literature regarding service design and development can, however, be identified. 1 The literature highlighted 2 key themes regarding services for people with YOD:

At the system level, the overwhelming evidence from the literature identified service integration as being critical. There is a need to integrate diagnostic services and to streamline the pathway to diagnosis and to relevant service support. The use of multidisciplinary team approaches and the development of more effective links between the range of services providing assistance to people with YOD, their carers, and families along the dementia journey are required. 2,33,40,43,114,143,166,168 -176

At the service level, people with YOD need to be consulted in the design and delivery of services designed to support them. Underpinning an individualized approach is the need for flexibility to accommodate individual and family circumstances as they change over time. 49,105,166,173 A key requirement is the need for age-appropriate services, 49,105,143,174,177 -180 providing meaningful, stimulating, and potentially beneficial activities.

Some authors also recommended the introduction of specialist services for YOD, 21,33,50,181 -183 and such services are increasingly available internationally. Given the relative rarity of YOD, for countries that have vast areas of sparse population such as Australia, access to specialist services in rural areas presents challenges. Effective outreach strategies (eg, teleconferencing, video conferencing, and Web links) will need to be included in the design of specialist services. 78,175,184 Given that many people with YOD may not be able to directly access specialist services, local dementia and disability services staff will also need education and training to assist both community and residential services 185 in addressing the particular needs of YOD clients.

The key service design attributes that were identified in the literature can be applied across a range of service types, both specialist and generic. The features of the service model, staffing, and organizational attributes are outlined in Table 1 and could readily be incorporated into many mainstream services.

Table 1.

Key Service Design Features.

| Individualized model of service 2,49,105 | Listening to people with younger onset dementia and their carers | Individualized service planning/person-centered approach | Recognition of the diversity among the many younger onset dementia diagnostic groups and the special needs of individuals |

| Ongoing needs assessment | Whole of family approaches | ||

| Staff attributes 2,49,166,168 | Appropriately skilled and suitable staff | An enabling and consumer-centered approach | Effective communication |

| An holistic approach | Case management skills | Flexibility | |

| Organizational attributes 2,49,105 | Access to integrated specialist diagnostic and ongoing symptom management services | Cost effective and flexible fees policy | Capacity building—involving people capable of effecting change in the process of service development |

| Capacity for organizational change/responsiveness | Cultural safety | Effective risk management strategies | |

| Regionally based, integrated, and coordinated interagency partnerships and pathways | Ability to cater for the needs of people in rural and remote communities | Appropriate exit policies relating to the suspension and withdrawal of services | |

| Timely service provision | Individualized service planning/person-centered approach | ||

| Dementia-friendly environments | Respect and consideration for clients and carers |

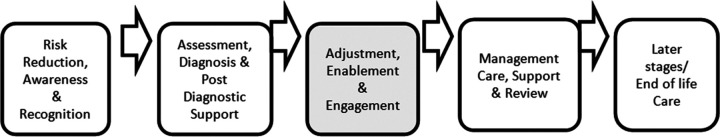

The concept of stages of the YOD disease trajectory is reflected in the literature as a useful concept for developing service responses for people with YOD. 33,74,105,186 In Australia, the Draft National Framework for Action on Dementia, 2013 to 2017, 187 identified 4 stages of dementia that relate to service delivery and design: risk reduction, assessment, management, and later stages of dementia/end of life. Due to the younger life stage of YOD, it was identified that an additional stage for people with YOD should be considered. Following diagnosis, a stage of “adjustment, enablement, and engagement” occurs (see Figure 2). Key elements of this stage are the adjustments in life made in response to the diagnosis of dementia. These include addressing their primary, family, and social relationships issues; developing new skills and strategies for remaining at work or transitioning to early retirement; and establishing financial and legal plans for the future. If people with YOD are appropriately supported during this critical stage, they may be able to maintain their independence for longer as well as preserving a sense of a “normality” and “control” in their changing lives.

Figure 2.

Five stages of younger onset dementia support.

Conclusion

This rapid 3 but comprehensive literature review was undertaken within an Australian policy context that may limit the generalizability of some of the findings to other jurisdictions/countries. It is also limited to English language articles so has excluded some contributions from other countries.

However, the service principles identified are generic in nature and so may be effectively applied to a range of YOD service settings internationally. Effective service provision for people with YOD in Australia will only be possible if health, aged care, and disability service sectors work collaboratively to provide a holistic approach to supporting people with YOD, their carers, and families.

To strengthen the evidence, there is a need for further studies with stronger research designs, larger sample sizes, a triangulation of methods of outcome assessment, and consideration of the control of potentially confounding factors to enhance evidence-based practice in this field.

Appendix A

Strength of Evidence 188,189

Well-supported practice—evaluated with a controlled trial (including cluster control) and reported in a peer-reviewed publication with no major design flaws evident.*

Supported practice—evaluated with a controlled trial group and reported in at least a government report or similar*; systematic literature review or epidemiological study including meta-analysis.

Promising practice—evaluated with a comparison to another comparable health system or service; epidemiological studies with acceptable methodology; literature review supported by a systematic search strategy.

Acceptable practice—evaluated with an independent assessment of outcomes but no comparison group (eg, pre- and postcomparisons, postreporting only, or uses systematic qualitative methods).

Emerging practice—evaluated without an independent assessment of outcomes (eg, formative evaluation, qualitative evaluation conducted internally; reviews of key articles not supported by a systematic search strategy).

Routine practice analysis—for example, analysis of routine and/or service utilization data for the service.

Opinionative articles—for example, from major advocacy bodies, editorials, or summaries from health professionals.

Case study—for example, one-shot case studies or a group of case studies that are largely anecdotal.

Other—for example, government policy statements and operational manuals, general information from Web resources, and so on.

*Where a controlled trial has design or implementation issues, this will be noted and the strength of evidence classification will be lessened.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The University of Wollongong received a grant from the Australian Government Department of Social Services.

References

- 1. Koopmans RT, Thompson D, Withalla A, et al. Services for people with young onset dementia. In: De Waal H, Lyketsos C, Ames D, O’Brien J, eds. Designing and Implementing Successful Dementia Care Services. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2013:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson D. Service and Support Requirements for People With Younger Onset Dementia and Their Families: Literature Review. Sydney, Australia: Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005;331(7524):1064–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Access Economics. Dementia Estimates and Projections: Australian States and Territories. Canberra, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia; 2005:37. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Dementia in Australia: National Data Analysis and Development. Canberra, Australia: AIHW; 2007:315. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Dementia in Australia. Canberra, Australia: AIHW; 2012:240. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brodaty H, Seeher K, Gibson L. Dementia time to death: a systematic literature review on survival time and years of life lost in people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(7):1034–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Broe T, KGOWS Team. NHMRC Koori Growing Old Well Study Update. Sydney: Neuroscience Research Australia; 2013. Web site. http://www.neura.edu.au/sites/neura.edu.au/files/page-downloads/KGOWS_UpdateAugust2013.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deloitte Access Economics. Dementia across Australia: 2011-2050. Canberra, Australia: Deloitte Access Economics Pty Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jorm AF, Dear KBG, Burgess NM. Projections of future numbers of dementia cases in Australia with and without prevention. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11-12):959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li SQ, Guthridge SL, Padmasiri E, et al. Dementia prevalence and incidence among the indigenous and non-indigenous populations of the Northern Territory, using capture-recapture methods. Med J Aust. 2014;200(8):465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith K, Flicker L, Lautenschlager NT, et al. High prevalence of dementia and cognitive impairment in Indigenous Australians. Neurology. 2008;71(19):1470–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Withall A. The challenges of service provision in younger-onset dementia. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2013;14(4):230–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Withall A, Draper B. Alcohol-related dementia: a common diagnosis in younger persons. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(4):s188–s189. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Withall A, Draper B, Seeher K, Brodaty H. The prevalence and causes of younger onset dementia in Eastern Sydney, Australia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(12):1955–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harvey RJ. The Impact of Young Onset Dementia: A Study of the Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Caregiving and Health Economics of Dementia in Younger People, in Imperial College School of Medicine. London, UK: University of London; 1998:288. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harvey RJ, Skelton-Robinson M, Rossor MN. The prevalence and causes of dementia in people under the age of 65 years. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(9):1206–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ikejima C, Yasuno F, Mizukami K, Sasaki M, Tanimukai S, Asada T. Prevalence and causes of early-onset dementia in Japan: a population-based study. Stroke. 2009;40(8):2709–2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kay DWK, Forster DP, Newens AJ. Long-term survival, place of death, and death certification in clinically diagnosed pre-senile dementia in northern England: follow-up after 8-12 years. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Livingston G, Cooper C. The need for dementia care services. In: De Waal H, Lyketsos C, Ames D, O’Brien J, eds. Designing and Delivering Dementia Services. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lobo A, Martinez-Lage J, Soininen H, et al. Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurology. 2000;54(11 suppl 5):S4–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Newens AJ, Forster DP, Kay DW. Dependency and community care in presenile Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(6):777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Picard C, Pasquier F, Martinaud O, Hannequin D, Godefroy O. Early onset dementia: characteristics in a large cohort from academic memory clinics. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(3):203–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prince M, Jackson J. World Alzheimer Report. London, UK: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2009:93. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vieira RT, Caixeta L, Machado S, et al. Epidemiology of early-onset dementia: a review of the literature. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2013;9:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:793–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferreira LK, Busatto GF. Neuroimaging in Alzheimer’s disease: current role in clinical practice and potential future applications. Clinics. 2011;66(suppl 1):19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Roman G, Pascual B. Contribution of neuroimaging to the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(8):671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Broe T. Koori growing older well study. 2013. Web site. http://www.neura.edu.au/aboriginal-ageing. Accessed 15 June 2015.

- 31. Ellis R, Langford D, Masliah E. HIV and antiretroviral therapy in the brain: neuronal injury and repair. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(1):33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Heaton RK, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bakker C. Young Onset Dementia: Care Needs and Service Provision. Nijmegen, Netherlands: Radboud University; 2013:160. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gibson AK, Anderson KA, Acocks S. Exploring the service and support needs of families with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2014;29(7):596–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sansoni J, Marosszeky N, Jeon YH, et al. Final Report: Dementia Outcomes Measurement Suite Project. Wollongong, Australia: Centre for Health Service Development, University of Wollongong; 2007:511. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Williams T, Cameron I, Dearden T. From pillar to post—a study of younger people with dementia. Psychiatr Bull. 2001;25:384–387. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alzheimer’s Australia. 2013 Younger Onset Dementia Summit: A New Horizon. 2013. Web site. http://www.fightdementia.org.au/services/2013-younger-onset-dementia-summit-a-new-horizon.aspx. Accessed 15 June 2015.

- 38. Hodges JR, Gregory C, McKinnon C, Kelso W, Mioshi E, Piguet O. Quality Dementia Care Series: Younger Onset Dementia A Practical Guide, in Quality Dementia Care Series. Sydney, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia; 2009:38. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Phillips J, Pond D, Goode SM. Timely diagnosis of dementia: can we do better? A report for Alzheimer’s Australia: Paper 24. Canberra, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia; 2011:44. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mocellin R, Scholes A, Velakoulis D. Quality Dementia Care: Understanding Younger Onset Dementia, in Quality Dementia Care Series. Melbourne, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia; 2013:52. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saunders P. Get Your Voice Heard: Living with Dementia in Country SA Report. Glenside, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia SA; 2013:71. [Google Scholar]

- 42. van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Aalten P, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in young-onset compared to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease—part 1: findings of the two-year longitudinal NeedYD-study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;34(5-6):319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ferran J, Wilson K, Doran M, et al. The early onset dementias: a study of clinical characteristics and service use. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1996;11:863–869. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burrell J. What is Younger Onset Dementia? Concord, Australia: Neuroscience Research Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boutoleau-Bretonnière C, Vercelletto M, Volteau C, Renou P, Lamy E. Zarit burden inventory and activities of daily living in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(3):272–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mourik J, Rosso S, Niermeijer M, Duivenvoorden H, Van Swieten J, Tibben A. Frontotemporal dementia: behavioral symptoms and caregiver distress. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(3-4):299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Riedijk S, De Vugt M, Duivenvoorden H, et al. Caregiver burden, health-related quality of life and coping in dementia caregivers: a comparison of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(5-6):405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bakker C, de Vugt ME, van Vliet D, et al. Unmet needs and health-related quality of life in young-onset dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(11):1121–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alzheimer’s Australia. 2009 Younger Onset Dementia Summit. 2009. Web site. http://www.fightdementia.org.au/services/2009-younger-onset-dementia-summit.aspx. Accessed 15 June 2015.

- 50. Beattie A, Daker-White G, Gilliard J, Means R. Younger people in dementia care: a review of service needs, service provision and models of good practice. Aging Ment Health. 2002;6(3):205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arends D, Frick S. Without warning(TM) lessons learned in the development and implementation of an early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease Program. Alzheimer’s Care Today. 2009;10(1):31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Clemerson G, Walsh S, Isaac C. Towards living well with young onset dementia: an exploration of coping from the perspective of those diagnosed. Dementia. 2014;13(4):451–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harris PB. The perspective of younger people with dementia. Soc Work Ment Health. 2004;2(1):17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Johannessen A, Möller A. Experiences of persons with early-onset dementia in everyday life: a qualitative study. Dementia. 2013;12(4):410–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Menne HL, Kinney JM, Morhardt DJ. ‘Trying to continue to do as much as they can do’: theoretical insights regarding continuity and meaning making in the face of dementia. Dementia. 2002;1(3):367–382. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pipon-Young FE, Lee KM, Jones F, Guss R. I’m not all gone, I can still speak: the experiences of younger people with dementia. An action research study. Dementia. 2012;11(5):597–616. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roach P, Keady J, Bee P, Hope K. Subjective experiences of younger people with dementia and their families: implications for UK research, policy and practice. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2008;18(2):165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alzheimer’s Australia. In Our Own Words: Younger Onset Dementia. Hawker, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Beattie A, Daker-White G, Gilliard J, Means R, ‘How can they tell?’ A qualitative study of the views of younger people about their dementia and dementia care services. Health Soc Care Commun. 2004;12(4):359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bunn F, Goodman C, Sworn K, et al. Psychosocial factors that shape patient and carer experiences of dementia diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 2012;9(10):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Harris PB, Keady J. Selfhood in younger onset dementia: transitions and testimonies. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(3):437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Reed P, Bluethmann S. Voices of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Summary Report on the Nationwide Town Hall Meetings for People with Early Stage Dementia. Washington DC: Alzheimer’s Association; 2008:33. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Armari E, Jarmolowicz A, Panegyres PK. The needs of patients with early onset dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2013;28(1):42–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tyson M. Exploring the Needs of Younger People with Dementia in Australia. Canberra, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia; 2007:96. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ducharme F, Kergoat MJ, Antoine P, Pasquier F, Coulombe R. The unique experience of spouses in early-onset dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2013;28(6):634–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Evans D, Lee E. Impact of dementia on marriage: a qualitative systematic review. Dementia. 2014;13(3):330–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hellström I, Nolan M, Lundh U. Sustaining ‘couplehood’: spouses’ strategies for living positively with dementia. Dementia. 2007;6(3):383–409. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kaiser S, Panegyres PK. The psychosocial impact of young onset dementia on spouses. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2007;21(6):398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Keady J, Nolan M. Family Care Giving and Younger People with Dementia: Dynamics, Experiences, and Service Expectations, in Younger People with Dementia: Planning, Practice, and Development. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley; 1999:203–222. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lockeridge S, Simpson J. The experience of caring for a partner with young onset dementia: how younger carers cope. Dementia. 2013;12(5):635–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mitchell H. Coping with Young Onset Dementia: Perspectives of Couples and Professionals. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 72. van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Bakker C, et al. Caregivers’ perspectives on the pre-diagnostic period in early onset dementia: a long and winding road. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(9):1393–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Bakker C, Koopmans RTCM, Verhey FRJ. Impact of early onset dementia on caregivers: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(11):1091–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bakker C, de Vugt ME, Vernooij-Dassen M, Van Vliet D, Verhey FRJ, Koopmans RTCM. Needs in early onset dementia: a qualitative case from the NeedYD study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2010;25(11):634–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Arai A, Matsumoto T, Ikeda M, Arai Y. Do family caregivers perceive more difficulty when they look after patients with early onset dementia compared to those with late onset dementia? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(12):1255–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Delany N, Rosenvinge H. Presenile dementia: sufferers, carers and services. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10(7):597–601. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nurock S. Carers and young onset dementia. J Br Soc Gerentol. 2000:10:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 78. O’Connell ME, Crossley M, Cammer A, et al. Development and evaluation of a telehealth videoconferenced support group for rural spouses of individuals diagnosed with atypical early-onset dementias. Dementia. 2014;13(3):382–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Allen J, Oyebode JR, Allen J. Having a father with young onset dementia: the impact on well-being of young people. Dementia. 2009;8(4):455–480. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Barca ML, Thorsen K, Engedal K, Haugen PK, Johannessen A. Nobody asked me how I felt: experiences of adult children of persons with young-onset dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(12):1935–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Garbutt NJ. The Experience of Having a Parent with Young-Onset Dementia during Transition to Adulthood. Leeds, UK: University of Leeds; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Millenaar JK, van Vliet D, Bakker C, et al. The experiences and needs of children living with a parent with young onset dementia: results from the NeedYD study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(12):2001–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nichols K, Fam D, Cook C, et al. When dementia is in the house: needs assessment survey for young caregivers. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40(1):21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Svanberg E, Spector A, Stott J. The impact of young onset dementia on the family: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Svanberg E, Stott J, Spector A. Just helping: children living with a parent with young onset dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(6):740–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Keenan KF, Miedzybrodzka Z, van Teijlingen E, McKee L, Simpson SA. Young people’s experiences of growing up in a family affected by Huntington’s disease. Clin Genet. 2007;71(2):120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Denny SS, Morhardt D, Gaul JE, et al. Caring for children of parents with frontotemporal degeneration: a report of the AFTD task force on families with children. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2012;27(8):568–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Luscombe G, Brodaty H, Freeth S. Younger people with dementia: diagnostic issues, effects on carers and use of services. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13(5):323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Bray JR. Young Carers in Receipt of Carer Payment and Carer Allowance 2001 to 2006: Characteristics, Experiences and Post-Care Outcomes. Canberra, Australia: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs; 2012:156. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hutchinson K, Roberts C, Kurrle S, Daly M. The emotional well-being of young people having a parent with younger onset dementia [published online April 29, 2014]. Dementia (London). 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. de Vugt ME, Riedijk SR, Aalten P, Tibben A, van Swieten JC, Verhey FRJ. Impact of behavioural problems on spousal caregivers: a comparison between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(1):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Baldwin RC. Acquired cognitive impairment in the presenium. Psychiatr Bull. 1994;18(8):463–465. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mackay N, Marriott A. Young onset dementia: carer’s experiences of services. PSIGE Newsletter. 2000;72:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Nicolaou PL, Egan SJ, Gasson N, Kane RT. Identifying needs, burden, and distress of carers of people with Frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia. 2010;9(2):215–235. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Miranda-Castillo C, Woods B, Orrell M. The needs of people with dementia living at home from user, caregiver and professional perspectives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Freyne A, Kidd N, Coen R, Lawlor BA. Burden in carers of dementia patients: higher levels in carers of younger sufferers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(9):784–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sait K. Living Alone With Dementia (Discussion Paper No. 7). North Ryde, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia NSW; 2013:44. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bakker C, de Vugt ME, Van Vliet D, et al. The use of formal and informal care in early onset dementia: results from the NeedYD study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lim J, Goh J, Chionh HL, Yap P. Why do patients and their families not use services for dementia? Perspectives from a developed Asian country. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(10):1571–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Georges J, Jansen S, Jackson J, et al. Alzheimer’s disease in real life—the dementia carer’s survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Husband HJ, Shah MN. Information and advice received by carers of younger people with dementia. Psychiatr Bull. 1999;23(2):94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Sussman T, Regehr C. The influence of community-based services on the burden of spouses caring for their partners with dementia. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(1):29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Easton A. The value of age appropriate services for those with younger onset dementia in The Power is Now: Moving on Dementia. Paper presented at: Alzheimer’s Australia’s 13th National Conference; 2009; Adelaide, SA. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bakker C, de Vugt ME, van Vliet D, et al. The relationship between unmet care needs in young-onset dementia and the course of neuropsychiatric symptoms: a two-year follow-up study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(12):1991–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Brown JA, Sait K, Meltzer A, Fisher KR, Thompson D, Faine R. Service and Support Requirements of People with Younger Onset Dementia and their Families. Final report. Sydney, Australia: NSW Department of Family and Community Services, Ageing, Disability and Home Care; 2012:164. [Google Scholar]

- 106. Harvey RJ, Roques PK, Fox NC, Rossor MN. CANDID—counselling and diagnosis in dementia: a national telemedicine service supporting the care of younger patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13(6):381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA). Reports on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2013:160. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Runge C, Gilham J, Peut A. Transitions in Care of People with Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Canberra, Australia: Dementia Collaborative Research Centres, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, University of Canberra; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Lindeman M, Taylor K, Kuipers P, Stothers K, Piper K. Evaluation of a Dementia Awareness Resource for Use in Remote Indigenous Communities. Darwin: Centre for Remote Health, Alzheimer’s Australia Research; 2010:42. [Google Scholar]

- 110. Blackstock KL, Innes A, Cox S, Smith A, Mason A. Living with dementia in rural and remote Scotland: diverse experiences of people with dementia and their carers. J Rural Stud. 2006;22(2):161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 111. Chaston D. Younger adults with dementia: a strategy to promote awareness and transform perceptions. Contemp Nurse. 2010;34(2):221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. LoGiudice D, Hassett A, Cook R, Flicker L, Ames D. Equity of access to a memory clinic in Melbourne? Non-English speaking background attenders are more severely demented and have increased rates of psychiatric disorders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(3):327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. LoGiudice DC, Smith K, Shadforth G, et al. Lungurra Ngoora—a pilot model of care for aged and disabled in a remote Aboriginal community—can it work? Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:2078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Moriarty J. Innovative practice section. Dementia. 2002;1(3):255–264. [Google Scholar]

- 115. LoGiudice D, Smith K, Thomas J, et al. Kimberley Indigenous Cognitive Assessment tool (KICA): development of a cognitive assessment tool for older indigenous Australians. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(2):269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Furniss KA, Loverseed A, Lippold T, Dodd K. The views of people who care for adults with Down’s syndrome and dementia: a service evaluation. Br J Learn Disabil. 2011;40(4):318–327. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Janicki MP, Zendell A, DeHaven K. Coping with dementia and older families of adults with Down syndrome. Dementia. 2010;9(3):391–407. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Birch H. Dementia, Lesbians and Gay Men, in Alzheimer’s Australia Paper 15. Canberra, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia; 2008:28. [Google Scholar]

- 119. Price E. Coming out to care: gay and lesbian carers’ experiences of dementia services. Health Soc Care Commun. 2010;18(2):160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods B, Orrell M. Psychosocial interventions in dementia care research: the INTERDEM manifesto. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(3):283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Burgener SC, Buettner LL, Beattie E, Rose KM. Effectiveness of community-based nonpharmacological interventions for early-stage dementia: conclusions and recommendations. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(3):50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Logsdon R, McCurry S, Teri L. Evidence-based interventions to improve quality of life for individuals with dementia. Alzheimers Care Today. 2007;8(4):309–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Pitkälä KH, Pöysti MM, Laakkonen ML, et al. Effects of the Finnish Alzheimer disease exercise trial (FINALEX): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Ratey JJ, Loehr JE. The positive impact of physical activity on cognition during adulthood: a review of underlying mechanisms, evidence and recommendations. Rev Neurosci. 2011;22(2):171–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Ryder-Jones C, Bullock A, Anderson L. Wii can make a difference. Aust J Dement Care. 2012;1(2):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 126. Knapp M, Thorgrimsen L, Patel A, et al. Cognitive stimulation therapy for people with dementia: cost-effectiveness analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Laudate TM, Neargarder S, Dunne TE, et al. Bingo! Externally supported performance intervention for deficient visual search in normal aging, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2012;19(1-2):102–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods B, Orrell M; INTERDEM Network. Psychosocial interventions in dementia care research: The INTERDEM manifesto. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(3):283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Spector A, Gardner C, Orrell M. The impact of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy groups on people with dementia: views from participants, their carers and group facilitators. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(8):945–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Banerjee S, Willis R, Matthews D, Contell F, Chan J, Murray J. Improving the quality of care for mild to moderate dementia: an evaluation of the Croydon Memory Service Model. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(8):782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Bird M, Caldwell T, Maller J, Korten A. Alzheimer’s Australia Early Stage Dementia Support and Respite Project. Final Report on the National Evaluation. Queanbeyan, Australia: Greater Southern Area Mental Health Service; 2005:52. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Davies-Quarrell V, Marland R, Marland P, et al. The ACE approach: promoting well-being and peer support for younger people with dementia. J Ment Health Train Educ Pract. 2010;5(3):41. [Google Scholar]

- 133. Goldberg EL. Filling an unmet need: a support group for early stage/ young onset Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. W V Med J. 2011;107(3):64, 66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Hayter C. Flexible and Responsive: Evaluation of the Younger Onset Dementia Social Support and Respite Program. Leichhardt, Australia: Carrie Hayter Consulting; 2008:37. [Google Scholar]

- 135. Kortte KB, Rogalski EJ. Behavioural interventions for enhancing life participation in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(2):237–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Shnall A, Agate A, Grinberg A, Huijbregts M, Nguyen MQ, Chow TW. Development of supportive services for frontotemporal dementias through community engagement. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(2):246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Sixsmith A. New technologies to support independent living and quality of life for people with dementia. Alzheimers Care Today. 2006;7(3):194–202. [Google Scholar]

- 138. Webster JJ, Duncan MA. Best practices. E-mail connections: an innovative communication network for families and persons with early-onset Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly. 2005;6(3):197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 139. Lindén A, Lexell J, Lund ML. Perceived difficulties using everyday technology after acquired brain injury: influence on activity and participation. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010;17(4):267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Arntzen C, Holthe T, Jentoft R. Tracing the successful incorporation of assistive technology into everyday life for younger people with dementia and family carers [published online April 29, 2013]. Dementia. 2014:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Jentoft R, Holthe T, Arntzen C. The use of assistive technology in the everyday lives of young people living with dementia and their caregivers. Can a simple remote control make a difference? Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(12):2011–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Lloyd-Yeates T. Working one-to-one with iPads. Aust J Dement Care. 2013;2(4):8. [Google Scholar]

- 143. Bentham P, La Fontaine J. Services for younger people with dementia. Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):84–87. [Google Scholar]

- 144. Letts L, Edwards M, Berenyi J, et al. Using occupations to improve quality of life, health and wellness, and client and caregiver satisfaction for people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65(5):497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Cook F. Medway Horticultural Project for Younger People with Dementia. Canterbury, England: St Martin’s; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 146. Hewitt P, Watts C, Hussey J, Power K, Williams T. Does a structured gardening programme improve well-being in young-onset dementia? A preliminary study. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76(8):355–361. [Google Scholar]

- 147. Spring JA, Viera M, Bowen C, Marsh N. Is gardening a stimulating activity for people with advanced Huntington’s disease? Dementia. 2014;13(6):819–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Kinney JM, Kart CS, Reddecliff L. ‘That’s me, the Goother’: evaluation of a program for individuals with early-onset dementia. Dementia. 2011;10(3):361–377. [Google Scholar]

- 149. Silverstein NM, Wong CM, Brueck KE. Adult day health care for participants with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2010;25(3):276–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Stansell J. A volunteer program for people with dementia. Alzheimers Care Today. 2001;2(2):4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 151. Evans D, Robertson J, Candy A. Use of photovoice with people with younger onset dementia [published online June 24, 2014]. Dementia (London). 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Robertson J, Evans D, Horsnell T. Side by Side: a workplace engagement program for people with younger onset dementia. Dementia (London, England). 2013;12(5):666–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Leuty V, Boger J, Young L, Hoey J, Mihailidis A. Engaging older adults with dementia in creative occupations using artificially intelligent assistive technology. Assist Technol. 2013;25(2):72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Casey J. Early onset dementia: getting out and about. J Dement Care. 2004;12(4):12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 155. Phinney A, Moody EM. Leisure connections: benefits and challenges of participating in a social recreation group for people with early dementia. Activities Adaptation Aging. 2011;35(2):111–130. [Google Scholar]

- 156. Moore K, Renehan E. Evaluation of Linking Lives Pilot: Supporting Younger People with Dementia. Final Report. Melbourne, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia Victoria; 2011:46. [Google Scholar]

- 157. Troy K, Zisis D. Case Management for Younger Onset Dementia: An Enabling Approach, in Younger Onset Dementia Forum. Sydney, Australia: Alzheimer’s Australia NSW; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 158. Willis R, Chan J, Murray J, Matthews D, Banerjee S. People with dementia and their family carers’ satisfaction with a memory service: a qualitative evaluation generating quality indicators for dementia care. J Ment Health. 2009;18(1):26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 159. Martin F, Turner A, Wallace LM, Bradbury N. Conceptualisation of self-management intervention for people with early stage dementia. Eur J Ageing. 2013;10(2):75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Ratcliffe J, Pezzullo L, Doyle C. Health economics, healthcare funding and service evaluation: international and Australian perspectives. In: De Waal H, Lyketsos C, Ames D, O’Brien J, eds. Designing and Implementing Successful Dementia Care Services. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2013:126–138. [Google Scholar]

- 161. Werner P, Stein-Shvachman I, Korczyn AD. Early onset dementia: clinical and social aspects. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(4):631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Bakker C, de Vugt ME, van Vliet D, et al. Predictors of the time to institutionalization in young- versus late-onset dementia: results from the Needs in Young Onset Dementia (NeedYD) study. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2013;14(4):248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Lloyd BT, Stirling C. Ambiguous gain: uncertain benefits of service use for dementia carers. Soc Health Illn. 2011;33(6):899–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Werner P, Goldstein D, Karpas DS, Chan L, Lai C. Help-seeking for dementia: a systematic review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28(4):299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Swaffer K. Prescribed Dis-Engagement: What is it? 2012. Web site. http://kateswaffer.com/2012/11/25/prescribed-dis-engagement/. Accessed 15 June 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 166. Alzheimer’s Society UK. Younger People with Dementia: A Guide to Service Development and Provision. London, UK: Alzheimer’s Society UK; 2005:41. [Google Scholar]

- 167. Morhardt D. Accessing community-based and long-term care services: challenges facing persons with frontotemporal dementia and their families. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45(3):737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Alt Beatty Consulting. Appropriate HACC Service Models for People with Younger Onset Dementia & People with Dementia and Behaviours of Concern: Issues for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds. Mosman, Australia: Alt Beatty Consulting for Community Care (Northern Beaches) Inc; 2008:60. [Google Scholar]

- 169. Callahan CM, Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos C. The historical development and state of the art approach to design and delivery of dementia care services. In: De Waal H, Lyketsos C, Ames D, O’Brien J, eds. Designing and Delivering Dementia Services. Chicester, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 170. Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, Morse GA, Miller J, Cruthis R. Recruitment, engagement, and retention of people living with HIV and co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders. AIDS Care. 2004;16(suppl 1):S56–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Hean S, Nojeed N, Warr J. Developing an integrated memory assessment and support service for people with dementia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(1):81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Wylie MA, Shnall V, Onyike CU, Huey ED. Management of frontotemporal dementia in mental health and multidisciplinary settings. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(2):230–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Whitfield K. Health Service Planning with Individuals with Dementia: Towards a Model of Inclusion. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Waterloo; 2006:296. [Google Scholar]

- 174. Brodaty H, Cumming A. Commentary: dementia services in Australia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(9):887–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Elliott T, Read K. Early onset dementia: developing strategies. J Dement Care. 2011;9(5):17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 176. Kenny R, Wilson E. Successful multidisciplinary team working: an evaluation of a Huntington’s disease service. Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;8(3):137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 177. Chemali Z, Schamber S, Tarbi EC, Acar D, Avila-Urizar M. Diagnosing early onset dementia and then what? A frustrating system of aftercare resources. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:81–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Hunt DC. Young-onset dementia: a review of the literature and what it means for clinicians. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2011;49(4):28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179. Tolhurst E, Bhattacharyya S, Kingston P. Young onset dementia: the impact of emergent age-based factors upon personhood. Dementia. 2014;13(2):193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180. Sansoni J, Samsa P, Owen A, Eagar K. A Model and Proposed items for the New Assessment System for Aged Care. Wollongong, Australia: Centre for Health Service Development, Australian Health Services Research Institute, University of Wollongong; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 181. Chaston D. Between a rock and a hard place: exploring the service needs of younger people with dementia. Contemp Nurse. 2011;39(2):130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182. Scott D, Donnelly M. The early identification of cognitive impairment: a stakeholder evaluation of a ‘Dementia Awareness Service’ in Belfast. Dementia. 2005;4(2):207–232. [Google Scholar]

- 183. Tindall L, Manthorpe J. Early onset dementia: a case of ill-timing? J Mental Health. 1997;6(3):237–250. [Google Scholar]

- 184. AIDS Dementia and HIV Psychiatry Service (ADAHPS). HIV complex needs case management project. 2013. Web site. http://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/adahps/index.asp. Accessed 15 June 2015.

- 185. Mulders AJMJ, Zuidema SU, Verhey FR, Koopmans RTCM. Characteristics of institutionalized young onset dementia patients—the BEYOnD study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(12):1973–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186. Keady J, Nolan M. Younger onset dementia: developing a longitudinal model as the basis for a research agenda and as a guide to interventions with sufferers and carers. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(4):659–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA). Consultation Paper: National Framework for Action on Dementia 2013-2017 (2013). Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia:25. [Google Scholar]

- 188. Coleman K, Norris S, Weston A, et al. NHMRC Additional Levels of Evidence and Grades for Recommendations for Developers of Guidelines STAGE 2 CONSULTATION Early 2008–End June 2009. NHMRC, Canberra. 2009.

- 189. Sansoni J, Duncan C, Grootemaat P, Samsa P, Cappell J, Westera A. Younger Onset Dementia: A Literature Review. Wollongong, Australia: Centre for Health Service Development, University of Wollongong; 2014. [Google Scholar]