Abstract

Most caregiver interventions in a multicultural society are designed to target caregivers from the mainstream culture and exclude those who are unable to speak English. This study addressed the gap by testing the hypothesis that personalized caregiver support provided by a team led by a care coordinator of the person with dementia would improve competence for caregivers from minority groups in managing dementia. A randomised controlled trial was utilised to test the hypothesis. Sixty-one family caregivers from 10 minority groups completed the trial. Outcome variables were measured prior to the intervention, at 6 and 12 months after the commencement of trial. A linear mixed effect model was used to estimate the effectiveness of the intervention. The intervention group showed a significant increase in the caregivers’ sense of competence and mental components of quality of life. There were no significant differences in the caregivers’ physical components of quality of life.

Keywords: dementia, family caregivers, minority groups, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

In Australia, cultural and linguistic diversity in the population aged 65 and older is greater than other age-groups, which reflects the post-Second World War immigration patterns. 1 This sociocultural context poses enormous challenges in providing culturally and linguistically appropriate care for people with dementia from these minority groups. The term “minority groups” in an Australian social context refers to the range of many groups that differ from the mainstream culture according to religion and spirituality, racial background, ethnicity, and language. 2 The prevalence of dementia in Australia is estimated to triple from 266 574 in 2011 to 947 624 in 2050. 3 Among this population, approximately a quarter (24%) were born in non-English speaking countries and most of them are cared for by family caregivers, as caring for older people is more commonly viewed as a family responsibility in these groups. 4,5 In 2012, a third of people with dementia who lived at home were from minority groups; in contrast only 19% of people with dementia residing in residential aged care facilities were from minority groups, suggesting that these groups were overrepresented in the community and underrepresented in residential care. 5

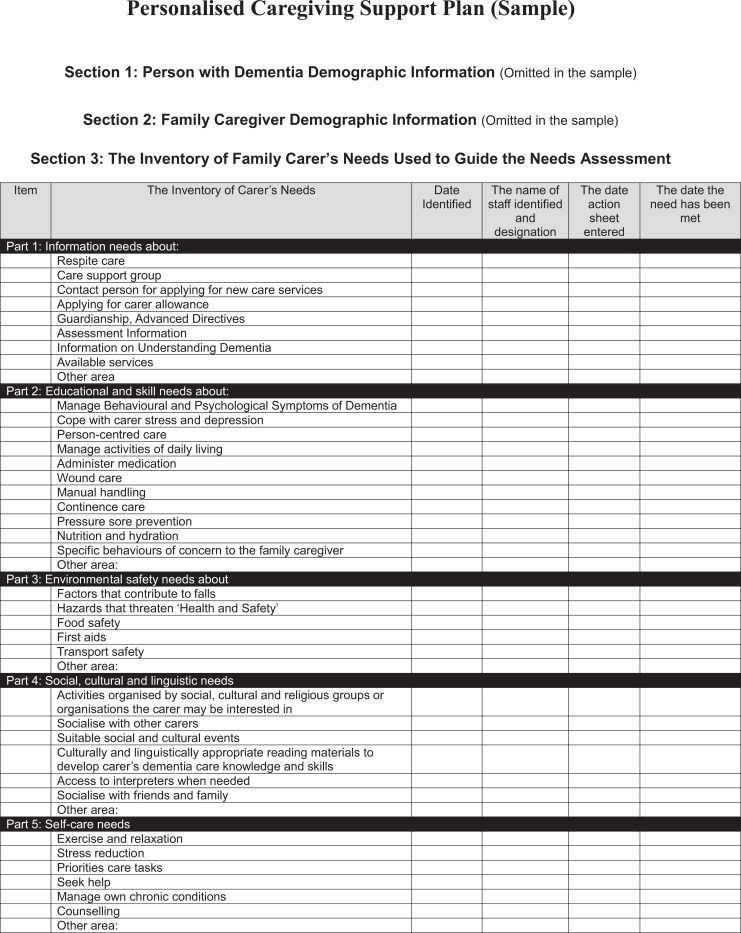

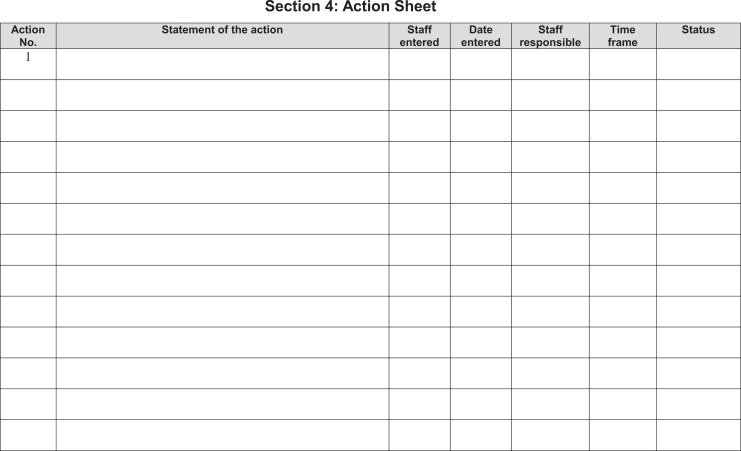

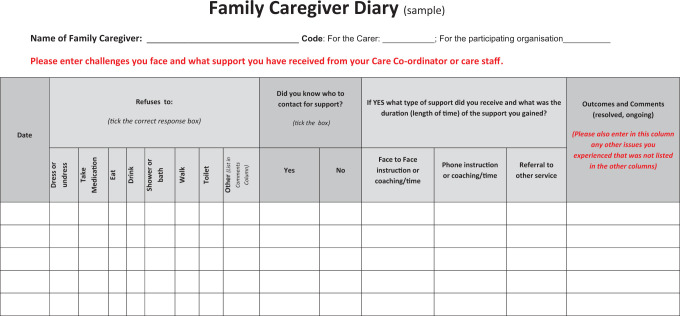

Although caregivers of the person with dementia from minority groups have a more significant role to play in managing dementia at home, most caregiver interventions in a multicultural society have been designed to target English-speaking caregivers from the mainstream culture and exclude those who do not speak English. 6 -8 This article reports a community care coordinator-led personalized dementia care intervention for caregivers from 10 minority groups. Two instruments, the “Personalized Caregiving Support Plan” (PCSP) and a “Caregiving Diary” (see Appendices A and B), were used as the intervention protocols. Bicultural and bilingual research assistants who each spoke the same language as the caregiver were trained to collect data in the intervention group.

It has been widely recognized that caring for a person with dementia at home puts a significant physical and psychological strain on caregivers due to the challenges of providing assistance with activities of daily living, of coping with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), and perceived changes in their relationship with the person with dementia. 9,10 Because of the progressive nature of the disease, dementia caregivers require on-going and hands-on assistance to address changes and challenges they encounter in daily care practice, their emotional and psychological distress, and their needs for information and other care services. 8,11,12 In Australia, although community care programs have been developed to relieve caregiver burden in order to support the person with dementia to stay at home as long as possible, they can be very difficult for caregivers to access. 9,10 Caregivers with limited English proficiency were found to have more difficulties in accessing care services and possessed fewer sources of care. 13,14

Case management has demonstrated improved intraorganizational and interorganizational collaboration in dementia services and caregivers’ ability to manage dementia. 7,8,15 Interventions in these studies included home-based coaching and tailored support to improve caregivers’ sense of competence, self-efficacy, quality of life (QoL), and relieve care burden. 7,8,15 Translating case management interventions is difficult considering the skill-mixed nature in the workforce and a low ratio of registered nurses to the clients in the community care setting in Australia. 16 Usually caregiver support is funded by the National Respite for Carers Program (NRCP) 5 and mainly relies on volunteers, who have limited education and training, to provide leisure activities and advice for caregivers.

Ethno-specific aged care services funded by the Australian Government are based on an ethnic, linguistic, or religious community providing a service to its own members and it has been used as a strategy to overcome the language barrier in accessing services. 4,17 Service providers under this category usually work with culturally and linguistically diverse minority groups and mainly employ bilingual and bicultural care workers to coordinate and deliver care. 14 The cultural and linguistic concordance between care staff and caregivers generates a possibility to trial a culturally and linguistically appropriate caregiver support using a case management approach.

This trial was conducted in partnership with 7 community care service providers, 5 of which were ethno-specific service providers. Prior to this trial, the 5 ethno-specific service providers had worked with the research team in a project to identify enablers and barriers perceived by family caregivers and care workers when caring for people with dementia from minority groups. 14

Methods

This study addressed the gap by testing the hypothesis that personalized caregiver support provided by a team led by a care coordinator of the person with dementia would improve competence for caregivers from minority groups in managing dementia.

Study Design

A randomized controlled trial was utilized to test the hypothesis. After baseline data collection, participants were randomly assigned to either an intervention group or the usual caregiver support group using simple random sampling methods.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was granted through the Social and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee of Flinders University (Project Number 5795). Letters of introduction and information sheets were provided in a language of choice. Caregivers who were willing to participate in the project were asked to provide their contact details on the “participants response slip” and return it via a prepaid, preaddressed envelope to the project leader. A bilingual researcher assistant then contacted the participant by phone to arrange a meeting to clarify information and explain the project to the caregivers. Informed consent was signed prior to the baseline interview with the caregivers.

Setting and Participants

The study was conducted in metropolitan Adelaide, South Australia. Participants were caregivers from minority groups who cared for the persons with dementia from the same minority group and were users of community aged care packages provided by the 7 service providers.

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria include: (1) caregivers were from a minority group and cared for a community–dwelling older person with dementia from the same minority group; (2) caregivers were the primary caregiver in the family; (3) caregivers had cared for the person with dementia for at least 1 year and had at least twice per week face-to-face contacts with the care recipients to ensure the intervention intensity required in the study was met; (4) caregivers were aged 18 or older; and (5) the care recipients had been diagnosed with dementia or had cognitive impairment determined by a score ≤22 of the 30 using the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS). 18 The RUDAS is a 6-item screening test that was specifically designed to minimize the impact of cultural differences on cognitive test performance. It has been validated in culturally diverse groups in Australia and internationally (sensitivity and specificity were 89% and 98%, respectively). 18 Caregivers were excluded from the trial if they themselves had cognitive impairment and/or a terminal illness or were in the first year of their caregiving role as there are a number of dementia education programs in Australia that target this period that may have affected the outcomes of the trial.

Interventions

Interventions used in this trial were mainly informed by a critique of current research evidence in case management intervention in caregiver support. 7,8,15,19,20 In addition, findings from previous studies by the research team and consultations with the participating organizations about resources to support the trial were considered. Participating organizations appointed 8 care coordinators to participate in the project and qualifications among them varied including a registered nurse, a social worker, and 6 Community Home Care Certificate holders. These coordinators were chosen based on their role working with people with dementia and experience with the caregiver population being studied. Each caregiver in the intervention group was assigned to a care coordinator who was currently managing the person with dementia cared for by the caregiver, and 7 of the coordinators had cultural and linguistic concordance with caregivers. The caseload for a care coordinator varied and ranged from 1 to 6 cases.

The care coordinators were trained to use the PCSP and a Caregiving Diary. “The Inventory of Carer’s Needs” in the PCSP covered the following 5 areas of caregiver support: information needs, educational and skill needs, environmental safety needs, social–cultural care needs, and self-care needs that reflect the current research evidence in dementia caregiver support. 7,8,15 The PCSP was used by the care coordinators when assessing caregivers’ needs, taking actions to address these needs, and evaluating the outcomes of their actions. The care coordinators encouraged the caregivers to use the Caregiving Diary to record challenges they faced in daily care practice in a language of choice. The Caregiving Diary was translated to the language of choice and structured in a simple table for the caregiver to enter. The use of the Caregiving Diary allowed care staff to identify care needs for care recipients and provide face-to-face coaching with caregivers and evaluate the effectiveness of care staff’s actions. The research team provided 3 standard training sessions with the care coordinators based on a consultation with them, that is, (1) using the Personalized Caregiving Support Plan and Family Caregiver Diary to identify and meet caregivers’ needs, (2) managing challenging behaviors, and (3) managing incontinence.

The care coordinators initially made a home visit to assess caregivers’ needs and establish the PCSP in collaboration with care staff who had regular contact with the person with dementia and their caregivers. The care coordinators made a monthly phone contact with caregivers to allow the caregivers to discuss the needs of care recipients and the caregivers. They also made a quarterly home visit to reassess caregivers’ needs and modify the PCSP. They referred caregivers to new services and education programs based on this needs assessment. When necessary, they organized conferences with caregivers and care staff to discuss ongoing challenges that the caregiver faced in order to identify the best solution to any problem identified. The usual caregiver support included activities such as monthly caregiver support group meetings and information sessions that were funded by the NRCP.

Sample Size, Data Collection, and Measures

The sample size was estimated based on an earlier RCT study using the “Sense of Competence Questionnaire” (SSCQ) as the primary outcome whereby 37 persons per group were required based on α = .05, a desired power of 0.80, and an effect size of 15% difference (mean 17.9, standard deviation 5.2). 7 The power calculation was recalculated based on the primary outcome and 3 secondary outcomes.

The effects of the trial were measured at 3 time points: prior to the trial, at 6 months, and 12 months after the commencement of trial. The selection of instruments used in the study was based on a comprehensive literature review. Primary outcome was caregivers’ competence measured by the SSCQ. 21 The 7-item SSCQ is a validated instrument (Cronbach’s α = .76.) and rated on a 5-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating the better sense of competence. Health-related QoL that was measured using the validated Short Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2). 22 Components of SF-36 have been translated into 2 summary dimensions: physical component (Cronbach’s α = .92) and mental component (Cronbach’s α = .88). Higher scores of QoL measured by the SF-36 mean better QoL.

The dependence levels of care recipients were measured using the validated “Blessed Dementia Score” (ranging 0-27; Cronbach’s α = .77) with higher scores meaning higher levels of dependence. 23,24 Severity of behavioral problems and caregiver distress were measured using the validated Neuropsychiatric Inventory (Cronbach’s α = .79-.86) with higher scores meaning higher levels of severity of behavioral problems and caregiver distress. 25 Satisfaction with care support was measured using the validated Quality Of Care Through the Patients’ Eyes (QUOTE-elderly) questionnaire-specific part (Cronbach’s α = .90). 26 Three items were added to the QUOTE-elderly questionnaire to ask about satisfaction with the cultural and linguistic appropriateness of the services provided. The 21-item satisfaction survey was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction with services received. The usage of respite care, aged care services, and dementia services was measures on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating the higher usage rates of these services. Content analysis of the PCSP and Caregiver Diary, and intervention fidelity were also analyzed. Demographic information about the caregivers and care recipients were collected prior to the trial only.

Nine bilingual and bicultural research assistants (2 male and 7 female) were employed to undertake data collection. They were community care workers who held a Community Home Care Certificate and had knowledge and skills in dementia care. All of them were born overseas and spoke the same language as the caregivers in the trial. Two 3-hour training sessions were provided for them to learn how to interview the caregivers, clarify the meaning of words used in the instruments, and discuss culturally sensitive issues they might encounter in data collection and strategies used to deal with these issues. The training was conducted in English as these research assistants all spoke English fluently.

Statistical Analyses

Data were entered into SPSS Statistics Version 22 for descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. 27 Baseline data between the intervention and usual care groups were compared using the Chi-square test for categorical measures and Mann-Whitney U test for skewed continuous measures. A linear mixed effect model was used to estimate the effectiveness of the intervention on the primary and secondary outcomes. The official Quality Metric Health Outcomes Scoring Software 4.0 was used to transform raw scale scores of the SF-36 to 0-100 scale and calculate means for the physical component summary scores and mental component summary scores. 22

Results

Demographic Information of Caregivers and Care Recipients

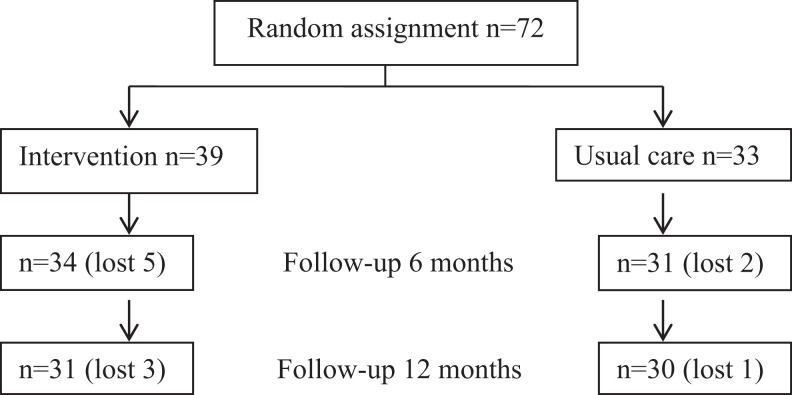

In total, 78 caregivers from 10 minority groups were recruited in the trial, 72 of them met selection criteria and 61 of them completed the trial at 12 months (see Figure 1). The cultural backgrounds of these caregivers were Cambodian, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, Greek, Hungary, Italian, Macedonian, Ukraine, and Vietnamese. Participant attrition during the 12-month follow-up is 11 including nursing home admission (5), death (4), and withdrawal (2).

Figure 1.

Study design and sample size.

The majority of caregivers in the study were female, children of the care recipients, born overseas, spoke a language other than English at home, and stayed in the same house with the care recipients. The median age of the caregivers was 56 years (range 26-89) and their median duration in the caregiver role was 4 years (range 1-25). The median hours spent on care per week were 12 hours (range 1-24). The intervention group had a higher proportion of overseas-born caregivers but otherwise there were no significant differences in demographic variables between groups (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Caregivers.a

| Items | Intervention, n = 31 | Usual Care, n = 30 | The Total, n = 61 | P Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | .99b | |||

| Male | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.7) | 10 (16.4) | |

| Female | 26 (83.9) | 25 (83.3) | 51 (83.6) | |

| Nonspouses or partners, n (%) | 23 (74.2) | 22 (73.3) | 45 (73.8) | .99b |

| Age, median (IQR) | 56.0 (50.0-69.0) | 56.0 (51.0-60.0) | 56.0 (50.0-65.0) | .97c |

| Born overseas, n (%) | 29 (93.5) | 20 (66.7) | 49 (80.3) | .02b, d |

| Language spoken at home other than English, n (%) | 30 (96.8) | 23 (76.7) | 53 (86.9) | .05b |

| Duration in the caregiver role, median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0-8.0) | 4.0 (2.0-6.0) | 4.0 (2.0-6.0) | .99c |

| Stay in the same house, n (%) | 20 (64.5) | 21 (70.0) | 41 (67.2) | .85b |

| Hours spent on care per week, median (IQR) | 12.0 (4.0-24.0) | 12.5 (6.5-24.0) | 12.0 (4.8-24.0) | .70c |

| Perceived financial burden, n (%) | 21 (67.7) | 21 (70.0) | 42 (68.9) | .99b |

| Received support from other family members, n (%) | 17 (54.8) | 20 (66.7) | 37 (61) | .59b |

| Number of chronic conditions, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0-3.0) | 1.0 (0.5-4.0) | 1.0 (1.0-3.0) | .45c |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

an = 61.

bChi-square test.

cMann-Whitney U test.

d P value <.05.

The majority of care recipients in the study were female with a median age 83 years (range 60-92) and median duration with dementia of 4.6 years (range 1-16). The median RUDAS score was 13.5 (range 0-22) and median Blessed Dementia Score was 12.8 (range 2-27). The care recipients were all born overseas and spoke a language other than English at home. There were no significant differences in demographic variables between the intervention and usual care groups (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Information of the Care Recipients.a

| Items | Intervention, n = 31 | Usual Care, n = 30 | The Total, n = 61 | P Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | .71b | |||

| Male | 11 (35.4) | 13 (43.3) | 24 (39.3) | |

| Female | 20 (64.5) | 17 (56.6) | 37 (60.7) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 83.0 (77.0-87.0) | 82.5 (76.0-86.0) | 83.0 (76.0-86.0) | .56c |

| Duration of dementia, median (IQR) | 4.6 (1.0-16.0) | 4.6 (1.0-13.0) | 4.6 (1.0-16.0) | .77c |

| Blessed dementia dependence score, median (IQR) | 13.4 (2.0-25.0) | 12.2 (3.0-27.0) | 12.8 (2.0-27.0) | .34c |

| Number of chronic conditions, median (IQR) | 2.2 (0-4.0) | 2.4 (0-4.0) | 2.3 (0-4.0) | .39c |

| RUDAS score, median (IQR) | 14.1 (0-21.0) | 12.9 (0-22.0) | 13.5 (0-22.0) | .81c |

Abbreviations: RUDAS, Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale; IQR, interquartile range.

an = 61.

bChi-square test.

cMann-Whitney U test.

The Effectiveness of Interventions on Caregivers

There were no significant differences in outcome measures at baseline between the intervention and usual care groups (see Table 3). Regarding the primary outcome measure, the intervention group demonstrated a steady increase in the caregivers’ competence (SSCQ) scores during the 12-month intervention compared with the usual care group (F = 15.76; P < .001, see Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparisons of Outcome Measures at Baseline Between Intervention and Usual Care Groups.

| Items | Intervention, n = 31 | Usual Care, n = 30 | P Valuesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire | 19.0 (16.0-22.0) | 19.0 (16.0-22.0) | .98 |

| Physical components score (PCS in SF-36) | 41.3 (38.7-48.1) | 45.7 (36.9-52.6) | .17 |

| Mental components score (MCS in SF-36) | 31.4 (26.4-33.9) | 28.2 (17.9-33.8) | .16 |

| Severity of care recipient’s BPSD | 7.0 (4.0-13.0) | 7.5 (5.0-12.3) | .65 |

| Caregiver distress | 8.0 (3.0-12.0) | 8.0 (5.0-14.0) | .73 |

| Usage of respite care | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .77 |

| Usage of caregiver support group | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | .15 |

| Usage of dementia helpline | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.00 |

| Satisfaction with service providers | 62.0 (33.0-69.0) | 59.5 (27.0-65.3) | .34 |

| Usage of community aged care | 1.0 (1.0-4.0) | 1.0 (1.0-4.0) | .93 |

| Usage of EACH | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .10 |

| Usage of EACH-D | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .15 |

Abbreviations: BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; EACH, community aged care at home; EACH-D, community aged care at home-dementia; SF-36, Short Form Health Survey.

aMann-Whitney U test.

Table 4.

Comparisons of Outcomes Between Intervention and Usual Care Groups.

| Outcomes | Intervention, n = 31, Mean (SD) | Usual Care, n = 30, Mean (SD) | F and P Values Using a Linear Mixed Effect Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire | Increased SSCQ in the intervention group | ||

| Baseline | 18.8 (4.5) | 18.7 (5.5) | T: F = 0.37 P = .69 |

| 6 Months | 21.1 (6.3) | 17.4 (5.3) | G: F = 15.76 P < .001a |

| 12 Months | 24.1 (6.8) | 15.0 (6.0) | T × G: F = 13.94 P < .001 power 99% |

| Physical components score (PCS in SF-36) | Decline over time of PCS in both groups | ||

| Baseline | 42.2 (7.2) | 44.9 (8.5) | T: F = 5.71 P < .01a |

| 6 Months | 41.8 (7.6) | 41.8 (8.5) | G: F = 0.31 P = .58 |

| 12 Months | 41.1 (7.7) | 41.6 (8.7) | T × G: F = 2.68 P = .08 |

| Mental components score (MCS in SF-36) | Increased MCS in the intervention group | ||

| Baseline | 30.3 (5.3) | 27.3 (10.9) | T: F = 2.87 P = .06 |

| 6 Months | 37.1 (8.2) | 24.7 (10.1) | G: F = 29.72 P < .001a |

| 12 Months | 38.7 (7.0) | 23.0 (8.6) | T × G: F = 22.35 P < .001 power 99% |

| Severity of care recipient’s BPSD | Stable over time in both groups | ||

| Baseline | 8.9 (6.5) | 9.3 (5.9) | T: F = 0.009 P = .99 |

| 6 Months | 7.7 (5.3) | 10.4 (7.2) | G: F = 3.23 P = .08 |

| 12 Months | 7.3 (4.7) | 11.0 (6.7) | T × G: F = 2.15 P = .12 |

| Caregiver distress | Stable over time in both groups | ||

| Baseline | 10.8 (9.4) | 11.2 (9.3) | T: F = 1.60 P = .21 |

| 6 Months | 6.5 (6.7) | 11.9 (11.7) | G: F = 3.79 P = .05 |

| 12 Months | 6.3 (6.6) | 13.1 (11.9) | T × G: F = 4.97 P = .01 |

| Usage of respite care | Increased over time in both groups | ||

| Baseline | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.0) | T: F = 21.13 P < .001a |

| 6 Months | 3.1 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.8) | G: F = 35.86 P < .001a |

| 12 Months | 3.5 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.1) | T × G: F = 10.53 P < .001 Power 99% |

| Satisfaction with service providers | Increased in intervention group and declined in usual care group | ||

| Baseline | 52.3 (21.1) | 49.8 (21.8) | T: F = 4.71 P = .01a |

| 6 Months | 64.1 (19.5) | 49.7 (19.0) | G: F = 12.56 P < .01a |

| 12 Months | 69.6 (12.8) | 44.4 (12.4) | T × G: F = 11.0 P < .001 Power 99% |

| Usage of community aged care | Increased over time in both groups | ||

| Baseline | 2.1 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.4) | T: F = 4.809 P = .01a |

| 6 Months | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.5) | G: F = 0.099 P = .75 |

| 12 Months | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.8 (1.5) | T × G: F = 0.30 P = .74 |

Abbreviations: T, effect of time; G, effect of treatment on the intervention group; T × G, interaction effect of time and treatment; BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; SD, standard deviation; SF-36, Short Form Health Survey; SSCQ, Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire.

a P value < 0.05.

In secondary outcome measures, the caregivers in the intervention group demonstrated a significant increase in the mental health components score of QoL compared with the usual care group (F = 29.72; P < .001), meaning an improved QoL. The increase was more noticeable in the first 6 months. Second, the caregivers in the intervention group demonstrated a significant increase in satisfaction with services compared with the usual care group (F = 12.56; P < .001). The usual care group showed a steady satisfaction score at 6-month follow-up, but a decrease in the score at 12-month follow-up, indicating a decrease in satisfaction. The change over time was significant in both groups (F = 4.71; P = .013). Third, the caregivers in the intervention group demonstrated a significant increase in the usage of respite care compared with the usual care group (F = 10.53; P < .001). The usual care group also showed a steady increase in the usage of respite care and the change was significant (F = 21.13; P < .001).

There were no statistically significant differences in scores of the physical components summary score of QoL, severity of care recipients’ BPSD, caregiver distress, the usage of caregiver support group, and the usage of community aged care packages.

Intervention Fidelity

The items of intervention fidelity recorded by both caregivers and care coordinators/care staff included (1) Caregiver Diary checked by care coordinator/care staff, (2) face-to-face instruction/coaching by care staff, (3) phone instruction/coaching by care coordinator, (4) home visit by care coordinators, (5) information provision by care coordinator, and (5) referral to Alzheimer’s Dementia Behavioral Management Advisory Service (see Table 5). The majority of care coordinators complied with the required interventions well and used The Inventory of Carer’s Needs and Caregiver Diary to identify caregiver’s needs and take actions to meet the needs. However, it was notable in the care plan that referrals to behavioral management were absent (see Table 5), although ongoing behaviors such as refusal to shower or bath, not taking medications, severe wandering at night, and aggressive behaviors toward caregivers or others in the respite care were recorded.

Table 5.

Summary of Intervention Fidelity Recorded by Care Coordinator/Care Staff and Caregivers.

| Items | Recorded by Care Coordinator/Care Staff | Confirmed by Caregivers |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Diary checked by care coordinator/care staff | Weekly | Yes |

| Face to face instruction or coaching by care staff | Weekly | Yes |

| Phone instruction or coaching by care coordinator | Monthly | Yes |

| Home visit by care coordinators | Quarterly | Yes |

| Information provision by care coordinator | On the basis of need | Yes |

| Referral to Alzheimer’s DBMASS | Nil | Nil |

Abbreviation: DBMAS, Dementia Behavioral Management Advisory Service.

Among the 31 caregivers in the intervention group, only 20 returned their Caregiver Diaries for analysis. All of those confirmed the compliance of required interventions (see Table 5). The majority who did not comply with the Caregiver Diary were mainly from an organization that experienced staff changes due to the change in funding to support the care coordinator. In addition, limited English proficiency and a low literacy level in caregivers’ first language were identified as barriers in using the Caregiver Diary to communicate with care staff in the present study.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that a modified case management intervention for caregivers from minority groups can be embedded in community aged care services using existing human resources and that the intervention can improve caregivers’ sense of competence in managing dementia. A number of factors may have affected the intervention fidelity and quality of interventions in the trial. First, the established partnership with participating organizations and the consultation with these organizations prior to the project about interventions ensured the support from these organizations. At the time of implementing the project, the consumer-directed care (CDC) model was introduced by the Department of Health and Ageing as part of the new aged care reform in Australia. 17 The participating organizations viewed the present study as an opportunity to explore suitable approaches to achieve CDC in the nearly future. Second, care coordinators in the present study had a lower caseload compared with other case management interventions that reported 10 to 40 person caseloads. 7,8 Third, the research team played a key role in facilitating quality of intervention through 3 standard training sessions, bimonthly site visits, and problem-solving support via phone and e-mail communication.

This intervention, in contrast to previous studies, had a positive impact on caregivers. A number of previous studies found that case management intervention had no positive impact on dementia caregivers due to lack of intervention intensity and poor quality of intervention, for example, no proactive actions to identify and meet caregivers’ needs in dementia care. 15,20 The present study considered these issues by encouraging caregivers to document care challenges in the Caregiver Diary. This intervention protocol encouraged caregivers to confront problems and develop an engagement coping style that contributed to problem solving and reduced the negative impact of these problems on caregiver’s health and well-being. 28,29 Studies report that a disengagement coping style in dementia caregivers contributes to prolong stressors and has a negative impact on caregivers’ mental health such as depression. 28,30 The Caregiver Diary can give cues to care staff to identify unmet caregiver needs of caregivers, assist in providing better solutions, facilitate help-seeking behaviors, and interactions with care staff. These are essential conditions for caregivers to learn to be competent caregivers.

Strategies including simplifying the Caregiver Diary by ticking predetermined common problems caregivers face, translating the Caregiver Diary into a language of choice, and asking other family members to help the record of problems, all improved the fidelity of this intervention protocol. Communication barriers have been identified as one of the key factors inhibiting caregivers who speak limited or no English from seeking support and services. 14,31 However, in the present study, this challenging issue was overcome by cultural and linguistic concordance between care coordinators and caregivers. In the situation of cultural and linguistic dissonance, the care coordinator needed to take a considerable longer time to organize family members or interpreters to assist the communication in phone support and home visit.

The use of the PCSP protocol addressed intervention intensity in a number of ways. First, as the persons with dementia were the users of community aged care, care staff had at least weekly contact with the person with dementia. They were required to liaise with the care coordinator to deliver the caregiver support intervention. This included checking the Caregiver Diary, discussing with caregivers about the issues of concern in daily care, coaching them about care knowledge and skills based on their needs, and reporting to the care coordinator if they were unable to resolve the issues. The intervention was much more intense compared with other similar reports in the literature. 7,8 Moreover, information exchanged between care coordinator and care staff allowed the care coordinator to update the care plan and take proactive actions to identify and meet caregivers’ needs, for example, by supplying information, referring caregivers to suitable education sessions, caregiver support groups, and new care services. The improved satisfaction with care services by the intervention group may be due to the established rapport between care coordinator/care staff and caregivers through regular caregiver support interactions. In the literature, many case managers were appointed through the research projects and had limited contact with care staff from care service providers. 7,15,20 Collaboration and communication between the case manager and care staff may be an issue that contributed to less effectiveness of interventions.

The significantly improved mental health components of QoL in the present study supports previous studies that used telephone interventions in caregiver support. 11,32 Coaching and supporting caregivers by telephone in previous studies assisted caregivers to adapt their role and develop positive appraisal of stressors. 11,32 The present study considered these components. In addition, culturally and linguistically appropriate support for caregivers to gain and comprehend information in dementia care and to refer them to services they needed may have also played a crucial role to reduce stressors caused by language barriers in managing dementia. Communication difficulties are widely recognized stressors in studies about caregivers from minority groups. 14,30,31

The present study showed no effectiveness on physical health components of QoL. This result may reflect the high dependence of the care recipients that requires higher levels of care services. The significant increase of respite care in both intervention and usual care groups may mirror the need for upgrading care service when dementia was progressing. However, at the time of this trial, the higher levels of care packages were allocated to community care organizations under a quota. Even when the persons with dementia had met the criteria to apply for care packages, they had to wait for the availability of the packages. 17 In the CDC model, consumers were given more autonomy to plan and control dementia services in the best interest of the person with dementia. However, the CDC has only been tested with a few selected service providers. 33 The present study, by exploring the caregiver-directed support, provided research evidence for future studies on CDC model in minority groups.

Unresolved challenging behaviors were reported in both the intervention and usual care groups. The Caregiver Diary from the intervention group supported the lack of case-specific interventions for challenging behaviors, for example, resistance to showering, not taking medications and aggressive behaviors toward caregivers. Behaviors are known to be the major cause of caregiver burden and caregiver distress. 34,35 The estimated prevalence rate of BPSDs in the community setting in Australia is 61% to 88%. 34 Most BPSDs are treatable through effective interventions by dementia care specialists, general practitioners, and care workers in collaboration with family caregivers. 34,36,37 The lack of case-specific interventions by coaching caregivers to identify and remove causes and triggers may indicate educational needs for care coordinators and care staff, as well as the caregivers.

This study has a number of limitations that may affect the outcomes and the translation of findings to other settings. First, this trial was built on an established partnership with participating organizations and agreement to assign the care coordinator and care staff to deliver the intervention components. Caregiver interventions were embedded in existing services. Selecting case managers outside these participating organizations may have generated different results in the trial. This partnership approach to trial was unable to blind participants to the intervention and usual care groups. Therefore, bias may exist throughout the trial. Second, due to the varied skill mix among the care coordinators, the research team played a problem-solving role throughout the project. This approach may affect the sustainability of the interventions after the project to facilitate the trial. In addition, cultural reasons might contribute to the incomplete caregiver diaries. Future studies will need to develop strategies to overcome this barrier when using this intervention protocol.

Conclusion

The trial demonstrated improved caregivers’ sense of competence in managing dementia and their mental well-being. Future interventions need to focus on tailored coaching for caregivers to manage BPSD and to utilize aged care and dementia care services to improve caregivers’ physical well-being. Based on the findings, it is strongly recommended that a personalized caregiver support using the Caregiver Diary, Inventory of Caregiver Needs, and PCSPs can be applied to caregivers who experience higher levels of care burden due to a lack of abilities to manage dementia at home regardless of their cultural backgrounds. Moreover, training bicultural and bilingual research assistants to undertake data collection is necessary to overcome not only language barriers but also sensitive cultural issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the participating organizations and family caregivers in this study in Adelaide, South Australia.

Appendix A

Personalised Caregiving Support Plan (Sample)

Appendix B

Family Caregiver Diary (Sample)

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding was provided by (1) the Dementia Collaborative Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia and (2) Flinders University Faculty Seeding Grants, Adelaide, Australia.

References

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Cultural diversity in Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2013. Web site. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2071.0main+features902012-2013. Accessed March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ziaian T, Xiao L. Cultural diversity in health care. In: Fedoruk M, Hofmeyer A, eds. Becoming a Nurse: Transition to Practice. 2nd ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2014:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deloitte Access Economics. Dementia across Australia: 2011-2050. Canerra: Deloitte Access Economics Pty limited; 2011. Web site. https://fightdementia.org.au/sites/default/files/20111014_Nat_Access_DemAcrossAust.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department of Health and Ageing. National Ageing and Aged Care Strategy for People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Backgrounds. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2012. Web site. http://www.fecca.org.au/images/stories/cald-aged-care/national-cald-aged-care-strategy.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Dementia in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2012. Web site. http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=10737422943. Accessed March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Charlesworth G, Burnell K, Beecham J, et al. Peer support for family carers of people with dementia, alone or in combination with group reminiscence in a factorial design: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jansen AP, van Hout HP, Nijpels G, et al. Effectiveness of case management among older adults with early symptoms of dementia and their primary informal caregivers: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(8):933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Samus QM, Johnston D, Black BS, et al. A multidimensional home-based care coordination intervention for elders with memory disorders: the maximizing independence at home (MIND) pilot randomized trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(4):398–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, Delepeleire J. Supporting family carers of community–dwelling elder with cognitive decline: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Fam Med. 2010;2010(8):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stockwell-Smith G, Kellett U, Moyle W. Why carers of frail older people are not using available respite services: an Australian study. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(13-14):2057–2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tremont G, Davis JD, Papandonatos GD, et al. Psychosocial telephone intervention for dementia caregivers: a randomized, controlled trial [published online July 26, 2014]. Alzheimers Dement. 2014. Web site. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. Spijker A, Wollersheim H, Teerenstra S, et al. Systematic care for caregivers of patients with dementia: a multicenter, cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang E, Chan KS, Han HR. Effect of acculturation on variations in having a usual source of care among Asian Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites in California. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiao L, De Bellis A, Habel L, Kyriazopoulos H. The experiences of culturally and linguistically diverse family caregivers in utilising dementia services in Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Somme D, Trouve H, Drame M, Gagnon D, Couturier Y, Saint-Jean O. Analysis of case management programs for patients with dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(5):426–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. King D, Mavromaras K, Wei Z, et al. The Aged Care Workforce, 2012. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2012. Web site. http://apo.org.au/files/Resource/DepHealthAgeing_AgedCareWorkforce1012_2103.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Department of Health and Ageing. Living longer. Living better. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2012. Web site. http://electionwatch.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/LaborLivingLongerLivingBetter.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Storey JE, Rowland JTJ, Conforti DA, Dickson HG. The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS): a multicultural cognitive assessment scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16(1):13–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Black BS, Johnston D, Rabins PV, Morrison A, Lyketsos C, Samus QM. Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: findings from the maximizing independence at home study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2087–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khanassov V, Vedel I, Pluye P. Case management for dementia in primary health care: a systematic mixed studies review based on the diffusion of innovation model. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:915–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vernooij-Dassen M, Felling AJA, Brummelkamp E, Dauzenberg MGH, van den Bos GAM, Grol R. Assessment of caregiver’s competence in dealing with the burden of caregiving for a dementia patient: A Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SSCQ) suitable for clinical practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(2):256–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ware JE. SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25(24):3130–3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blessed G, Tomlinson B, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114(512):797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gallo JJ, Paveza GJ. Activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living assessment. In: Gallo JJ, ed. Handbook of Geriatric Assessment. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2006:193–240. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenbergthompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The neuropsychiatric inventory—comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sixma HJ, van Campen C, Kerssens JJ, Peters L. Quality of care from the perspective of elderly people: the QUOTE-Elderly instrument. Age Ageing. 2000;29(2):173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. IBM. SPSS Statistics Version 22 Armonk, New York: IBM Corporation; 2013. Web site. http://www14.software.ibm.com/download/data/web/en_US/trialprograms/W110742E06714B29.html. Accessed March 12, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. García-Alberca JM, Lara JP, Garrido V, Gris E, González-Herero V, Lara A. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the role of caregiver burden and coping strategies. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2014;29(4):354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McClendon MJ, Smyth KA. Quality of informal care for persons with dementia: dimensions and correlates. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(8):1003–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun F, Ong R, Burnette D. The influence of ethnicity and culture on dementia caregiving: a review of empirical studies on Chinese Americans. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2012;27(1):13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Benedetti R, Cohen L, Taylor M. “There’s really no other option”: Italian Australians’ experiences of caring for a family member with dementia. J Women Aging. 2013;25(2):138–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Mierlo LD, Meiland FJM, Droes RM. Dementelcoach: effect of telephone coaching on carers of community–dwelling people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(2):212–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Department of Health and Ageing. Consumer Directed Care Evaluation. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2012. Web site. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/10_2014/evaluation-of-the-consumer-directed-care-initiative-final-report.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brodaty H, Draper B, Low L. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a seven-tiered model of service delivery. Med J Aust. 2003;178(5):231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gallagher-Thompson D, Tzuang YM, Au A, et al. International perspectives on nonpharmacological best practices for dementia family caregivers: a review. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35(4):316–355. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295(18):2148–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnson DK, Niedens M, Wilson JR, Swartzendruber L, Yeager A, Jones K. Treatment outcomes of a crisis intervention program for dementia with severe psychiatric complications: the Kansas bridge project. Gerontologist. 2012;53(1):102–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]