Abstract

The physical environment of dining rooms in long-term care facilities is increasingly recognized as an important catalyst in implementing a culture based on person-centered care philosophy. Mealtimes are important opportunities to support residents' personhood in care facilities. This article presents a critical review of the literature on evidence-based physical environmental interventions and examines their implications for creating a more person-centered dining environment, specifically for residents with dementia. The review identifies the role of a supportive dining environment to foster: a) functional ability, b) orientation, c) safety and security, d) familiarity and home-likeness, e) optimal sensory stimulation, f) social interaction, and g) privacy and personal control. It is clear from this review that there is a growing body of research to support the importance of certain physical environmental features in the dining context that can foster positive resident outcomes. The evidence indicates that well-designed physical settings play an important role in creating a person-centered dining environment to support best possible mealtime experience of residents. Gaps in the literature and directions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: physical environment, mealtimes, dining, person-centered care

Introduction

Person-centered care is a best practice concept guiding efforts to improve residents’ quality of life in long-term care facilities. The care philosophy recognizes that individuals have unique values, personal history, and personality. Kitwood who advocated for person-centered care stressed the importance of taking a holistic perspective in relating to and caring with the person with dementia. 1 He defined personhood as “a standing or a status that is bestowed on one human being, by another in the context of relationship and social being.”1(p8) Drawing on Buber’s 2 2 distinct ways of relating I-Thou (I am with you authentically) and I-It (I relate to another as object), Kitwood’s work provided a conceptual lens to view how care practice may undermine or support personhood of people with dementia in care settings. For example, including a person with dementia in conversations at mealtimes would be considered as “positive person work,” as it contributes to recognizing that person as a valued person. Another notable scholar, Brooker 3 illustrated Kitwood’s philosophy of person-centered care in a “VIPS” framework—“V” as valuing the individual as a full member of society, “I” as providing individualized approach, “P” as understanding the perspective of the person living with dementia, and “S” as providing a social environment that supports well-being of the person.

Person-centered dementia care requires shift in attitudes, behaviors, and systems replacing the traditional model of care that primarily focuses on the “tasks.” Care providers need to move from a negative disabling approach to a more positive enabling mind-set that respecting residents as adults who have rich histories and can live meaningful lives. 4 –6 Over the last 2 decades, there has been a growing body of literature 7 –11 that has recognized and provided evidence on the effect of unsupportive physical environments that contribute to common challenging behaviors in people with dementia, for example, spatial disorientation, anxiety or agitation, social withdrawal, and so forth. On the other hand, a well-designed supportive physical environment has been shown to reduce challenging behaviors and foster positive ones, such as lower agitation, increase in social contact, less dependence in conducting activities of daily living, and so forth. In the recent past, the physical environment has been increasingly recognized as an important factor in transforming the culture of long-term care to become more person centered. 4,12,13 Making appropriate environmental modifications to support individual resident’s routine, preference, and needs is a crucial indicator of person-centered care that essentially honors the identity of residents, support quality of life, and well-being of residents with dementia. Inappropriate physical environment of the dining room is one of the most frequent concerns voiced by staff in nursing homes. Dining rooms are often loud and overstimulating places in care homes. As Briller et al 14 describe, memory problems, cognitive, and functional impairment associated with dementia put the persons with dementia more vulnerable to environmental influences.

Mealtimes are important opportunities to support residents’ personhood 4 ; a pleasurable dining experience affects residents’ perception of well-being and is inextricably linked with their quality of life. 14 Not only a time for nourishment, but mealtimes have connections to special events, significant memories of one’s lifetime, and lifelong habits. 14 Mealtimes are, therefore, of cultural, social, and psychological importance for older adults. Venturato 15 notes that mealtime rituals can protect dignity, honor, and personal identity in adapting to the experience of cognitive decline. 16 –18 The routines and traditions associated with eating are especially important to maintain cultural ideals for older immigrants living with dementia. 19 Thoughtfully designed environments not only present valuable therapeutic resource in supporting cultural, social, and psychological needs of the residents with dementia but also enable staff to care for residents in an effective and person-centered way. The physical environmental features and the social context are interrelated factors that influence the dining experience of residents. For example, a smaller and homelike dining room would influence a smaller group size of the residents having meals in that space, which in turn would likely facilitate more familiar social stimulations and allow staff to offer care in more personalized and flexible ways. Although there may be no single environmental design solution for any given setting or population, 20 studies consistently support the benefits of mealtime settings that offer a small intimate homelike atmosphere. 21 –25 Regarding the concept of personhood, the physical environment has been highlighted in its ability to both promote and impede personhood among residents with dementia. 4

In 2008, almost half a million Canadians were living with dementia, and the prevalence is expected to be more than double in the next 30 years as the population of older adults grows. 5 It has been estimated that 48% to 94% of the residents in long-term care facilities have some form of dementia. 26,27 As the societal incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias increases, research on the dining experience of persons with cognitive impairment is much needed to support the responsive practice in long-term care. This article reviews the extant literature on the role of physical environment of the dining rooms in long-term care facilities in supporting person-centered care. The research question that guided this review was “What is the role of physical environmental features of dining rooms on positive outcomes of the dining experience among residents with dementia in long-term care facilities?” In this study, “dining experience” is defined as a broad concept consisting of both physiological and sociopsychological aspects of dining, including caloric intake, enjoyment in eating, social interaction, and so forth.

Methods

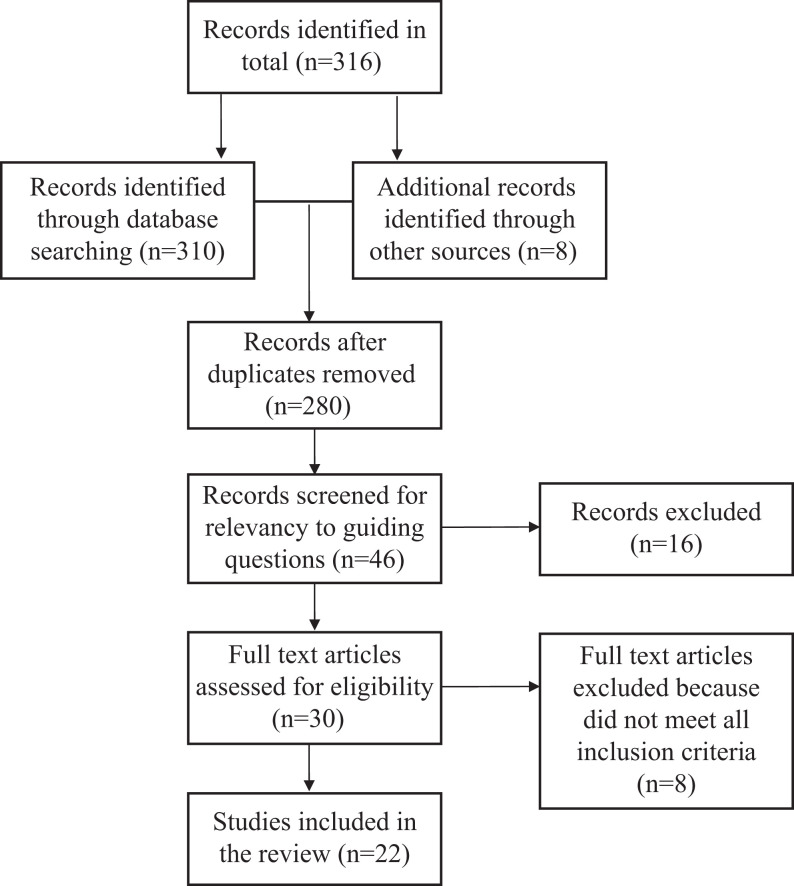

Two coauthors conducted a key word search of major research databases to identify potentially relevant studies for this review. These databases include CINAHL, Ageline, Medline, Web of Science, and Simon Fraser University library catalogue. The search terms used included person-centered care, care services, dementia, physical environment, design, dining, dining environment, long-term care, mealtime, food satisfaction, nutrition, cognitive status, buffet-style dining, and quality of life. The guiding research question helped us to determine the scope of the literature search and to formulate the inclusion and exclusion criteria of relevant items. Inclusion criteria for this review were (1) the article described the results of empirical research; (2) the physical environment of the dining rooms in long-term care was explicitly addressed; and (3) the article was published in English from 1990 or later. Duplicates and non-English language articles were excluded as were articles that were specific to food qualities, meal services, and so forth and did not include any reference to the physical environment of the setting. Articles were also omitted if they reported on environmental interventions that were outside of long-term care settings; trade magazines were excluded because of potential confounding issue with marketing/sale promotions. A total of 22 journal articles were included in this review, 12 of which were intervention studies. These articles have been summarized in Table 1. Selected Web sites and text literature (eg, Alzheimer Society Canada, Pioneer Network, books, and conceptual publications on environmental design in dementia care) were also included in the review to provide general background information. The initial search resulted in the retrieval of 316 abstracts; these abstracts were screened to identify duplications and assessed with inclusion and exclusion criteria. Figure 1 gives an overview of the selection process for inclusion of the literature items. All authors read the selected articles independently. The reviews were compared and discussed among the authors to establish consensus. The methodological assessment of the quantitative research-based articles was focused on research method, sample size, representativeness, data collection, data analysis, and results. Qualitative studies were evaluated for clarity of focus, sampling and data collection methods, findings, and criteria (eg, triangulation) supporting the validity and the reliability. The data synthesis process consisted of a critical review of the main focus, research methods, major findings, and identifying limitations. This review and synthesis were part of a larger empirical study that investigates the effects of pre- and postenvironmental renovations of dining rooms in a long-term care facility in Canada.

Table 1.

Summary of the Research on Physical Environment of Dining Room in Long-term Care Facilities.

| Reference | Main Focus | Methods | Main Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrick et al 55 | Effect of ambient bright light therapy in activity and dining areas among institutionalized persons with dementia. | Intervention, multiple 3-week period totaling 338 three-week intervention periods | In comparison to standard lighting, ambient bright light did not reduce agitation in dementia, in fact it may exacerbate agitation. | Did not assess any outcome measures beyond agitation, potential for treatment effect if less agitated patients were discharged |

| Brush et al 34 | Effect of improved lighting and table setting contrast on residents’ oral intake behaviors at mealtimes in assisted living and nursing homes serving | Pilot study, intervention Baseline + posttest after 4 weeks | Increased caloric intake and functional abilities following lighting and contrast intervention | Small sample size, n = 25 pilot study, change in staffing policy midway through research may have inflated COMFI scores. |

| Crogan et al 21 | Examine meaning of food and perspectives of food and foodservice among nursing home residents | Qualitative, interpretational phenomenological | Improvements to meal service should aim to mimic family dining (eg, tablecloths, placemats, no serving trays, and small dining tables) | Sample size, n = 9, sample age, majority under age 60 (n = 5) |

| Denney 52 | Effect of quiet music (peaceful and melodic, classical) on the incidence of agitated behaviors during mealtimes among older adults with dementia residing in a special care unit. | Intervention, repeated measures over 4 week period | Reduced incidence of agitated behavior when quiet music played during mealtime; verbally agitated and physically nonaggressive behaviors most changed | Convenience sample, n = 10, lunch mealtime only |

| Desai et al 22 | Compare energy intake among seniors with cognitive impairment in long-term care after changes made in foodservice and the physical environment of the dining room. | Quantitative, secondary data analysis 21 consecutive day energy intake, macronutrient intakes, behavioral function | Bulk foodservice delivery (cafeteria style with waitress service) and homelike dining environment optimizes the energy intake of seniors with low BMI and cognitive impairment. | Unequal sample and control groups, exact alterations to physical environment unspecified |

| Dunne et al 37 | The effect of contrast manipulations on food and liquid intake among persons with Alzheimer’s disease in long-term care. | Intervention, baseline measures based on white tableware; intervention measures based on high-contrast red tableware. | The high-contrast intervention increased food intake by 25% and liquid intake by 84% versus baseline condition. | Small sample size of older men only (n = 9) |

| Hicks-Moore 53 | Relationship between relaxing music and agitated behaviors among nursing home residents with dementia. | Quasiexperimental, intervention | Reduction in the overall level of agitation associated with playing relaxing music during evening mealtimes. | Gender bias (female, 70%) |

| Hung and Chaudhury 4 | Relevance and applicability of “personhood” concept during mealtimes for persons with dementia in long-term care. | Qualitative approach, ethnography, conversational interviews, participant observations, staff + resident focus groups | Important role of physical environment to create intimate and homelike dining experience for residents with dementia. | Difficult to replicate |

| Lam and Keller 19 | Meaning of the mealtime experience and how identity is honored among community-dwelling Chinese Canadian immigrant families with dementia to expand the Life Nourishment Theory | Qualitative Dyad/triad family and individual interviews | Life Nourishment Theory concept of honoring identity through mealtimes relevant to this ethnocultural minority group. Mealtimes necessary for maintaining routines and reaffirming family and self identity. | Sample (n = 6) and homogeneous sample recruited from adult day program, with gender bias (male, n = 5) |

| McDaniel et al 36 | Effect of noise and lighting conditions at mealtimes on food intake of ambulatory dementia residents | Quantitative Comparative case study | Lighting enhancement and noise reduction associated with greater 5-day nutritional intake | Small sample size (n = 16) Homogenous sample (veterans, male n = 15) |

| Nijs et al 45 | Effect of family style mealtimes versus preplated meal service on the quality of life, physical performance, and body weight of residents without dementia | Randomized controlled trial conducted over 6 months | Family style mealtimes prevented a decrease in quality of life; improved mealtime ambience prevented a decline in physical performance, and body weight | Lacks qualitative data Did not include persons with dementia |

| Nolan and Mathews 42 | Reducing resident agitation at mealtimes through simple modifications to dining room environment, that is, hanging large clock and print sign indicating mealtimes | Quantitative, intervention Direct observations over 5-month period | Environmental modifications reduced confusion about mealtimes and increased resident–resident interactions | Sample size, n = 35 |

| Passini et al 41 | Generate design guidelines to facilitate wayfinding in long-term care environments for persons with advanced Alzheimer’s. | Qualitative Staff interviews and wayfinding task | Wayfinding complicated by a number of factors including repetitive environments; names given to spaces should reflect the space’s function; functions should remain stable, that is, dining has a permanent locale and permanent furniture arrangements. | Limited samples (staff n = 10; residents n = 6) Gender bias (all female) |

| Perivolaris et al 27 | Effectiveness of the Enhanced Dining Program intervention (environmental modifications and staff education) in addressing the dining experience of individuals with dementia in long-term care. | Intervention Repeated measures (baseline, week 6, and week 12). | The intervention contributed to increased caloric intake; importance of both environmental modifications and staff education regarding person-centered care versus alterations to physical environment alone | Small sample size, n = 10 Male bias (n = 8) |

| Philpin et al 57 | Sociocultural factors influencing nutritional care in two different long-term care settings. | Qualitative, focus group interviews with staff, individual interviews with managers as well as residents and informal carers, observations of food preparation and mealtimes, document analysis | Spatial surroundings in dining areas influenced social interaction; family style dining enhanced sociability and enjoyment at mealtimes which further encouraged eating; shared mealtimes and food preparation conferred a sense of normality, community and identity; mealtimes important to structure the rhythm of daily life. | Purposive sampling Exclusion of individuals with cognitive impairment |

| Ragneskog et al 51 | Effect of different dinner music on behavioral symptoms of nursing home residents with severe dementia | Quantitative 11-week intervention Video-recorded observations | Soothing dinner music may preferably benefit mealtime behavior, increase time spent eating dinner | Small sample size, n = 5 Effects indirectly assessed through nursing staff, limited scope of behavior, results may be due to sequential effects of music |

| Reed et al 47 | Describe characteristics associated with nutritional intake of residents with dementia. | Mixed methods | Low food intake associated with cognitive impairment; residents in small facilities have better food outcomes due to increased staff assistance during meals; residents in dining areas with less institutional features less likely to have low food and fluid intake. | Focus on fluid and food intake rather than nutritional content Intake during single-meal recorded rather than overall daily intake Lacks operationalization of “institutional features” |

| Roberts 23 | Impact of dining room design features on patterns of resident socialization and interaction at mealtimes. | Case study over 6 week period Ecological theoretical framework, field notes, and staff interviews | Residents’ socialization and interaction influenced by complex interrelation of operational, managerial, and environmental features of dining room setting. | Difficult to replicate Focus on observable behavior only |

| Schwarz et al 48 | Effect of design renovations on desirable behavioral outcomes in nursing home residents with dementia | Mixed methods, intervention, Professional Environmental Assessment Protocol; behavioral mapping; focus-group interviews with staff members | Fewer incidents of disruptive behaviors and more sustained conversation between staff and residents in renovated dining area. | Resident characteristics unspecified |

| Thomas and Smith 50 | Mealtime music at lunch to decrease agitation and thus improve total caloric intake. | Intervention, mixed methods Time-series crossover design | Caloric consumption increased by 20% with familiar mealtime music playing as compared to dining without dinner music; increased calories consumed primarily through carbohydrates. | Small sample size, n = 12 Female gender bias (n = 11). restricted to lunchtime music |

| Ullrich et al 49 | Improve nutritional care and mealtime experience for older adults in residential care by implementing the Protected Mealtimes initiative to change nursing practice and the mealtime environment. | Qualitative Participatory action research | Protected Mealtimes initiative was effective in creating time for nurses to reconnect with nutritional care, understand and extend their roles in nutritional care, and motivate resident-focused long-term changes in the mealtime experience | Setting specific Lacks pre/posttest design Nondementia sample |

| West et al 25 | Resident and staff beliefs regarding foodservices to examine its relation to health status, quality of life, and autonomy of the residents in long-term care. | Quantitative Interview questionnaires | Residents placed greatest importance on respect, feeling at home, comfort, variety, and appetizing meals; rated choice and autonomy lower in importance but were generally dissatisfied with these items. Staff believed technical aspects of foodservice to be most important to residents and overlooked food preferences; overrated importance of social environment to residents. | Small sample and bias toward French-Canadians (residents n = 69, staff n = 52) |

Figure 1.

Process of selecting studies for the review.

Results

We found a small but growing number of studies that examined the relationship between the physical environment of dining rooms in long-term care facility and the resident outcomes. Overall, the evidence confirms that appropriately designed physical settings play an important role in creating a person-centered dining environment to support best possible mealtime experience for the residents. Person-centered care is value driven, focuses on independence, well-being, and abilities of residents, and it enables the person to feel supported, valued, and socially confident. 1 Person-centered care recognizes that dementia does not diminish a person but changes a person’s capacity to interact with his or her social and physical environments. 3 As the importance of the physical environment of the overall care home in creation of a person-centered dementia care setting has been recognized previously, 13 this review identified the role of the physical environment of the dining room to support individual residents’ abilities, preferences, and habits.

The broader literature on environmental design for people with dementia has outlined several therapeutic goals for the physical environment of a dementia care setting, 28 –33 such as “maximize safety and security,” “support functional abilities,” “maximize awareness and orientation,” “facilitate of social contact,” “provision of privacy,” “regulation of stimulation,” and so forth. These goals reflect indicators that capture the essence of physical environment’s role in supporting person-centered care. Based on our review and synthesis of the literature focusing on physical environment in dining rooms, we identified 7 therapeutic goals that were most relevant and meaningful in the context of mealtimes and dining room. These were (1) supporting functional ability, (2) maximizing orientation, (3) providing a sense of safety and security, (4) creating familiarity and homelikeness, (5) providing optimal sensory stimulation, (6) providing opportunities for social interaction, and (7) supporting privacy and personal control. These selected therapeutic goals served as conceptual framework to synthesize the substantive research findings in this body of literature.

Supporting Functional Ability

Modifications in the environment can improve the dining experience of the residents with dementia by compensating for cognitive impairment and functional disabilities. The literature suggests one important way to support abilities of the residents which is by providing appropriate lighting. Uniform soft light is needed to illuminate food and prevent glare. 33,34 As older adults may require additional time adjusting to changes in light levels, a mixture of indirect and direct lighting is recommended to reduce eyestrain and improve depth perception. 14,34 Guidelines suggest the minimum level of ambient light during dining to be at least 50-ft candles, 35 where an even distribution of light may be best effected through combined pendant and cove lighting. 30 Regarding table settings, Briller et al 14 suggest for table tops, place mats, and dishware to be strongly contrasting in color. Since persons with Alzheimer’s disease may have reduced contrast sensitivity, such design may help to improve differentiation between these items. 34 Flooring should be of a low-contrast pattern in order to prevent distraction.

McDaniel et al 36 investigated the association between mealtime lighting, noise, and nutritional outcomes. The results of their study suggest that enhanced lighting (including increased illumination and decreased glare) as well as noise reduction is associated with a greater nutritional intake among residents with Alzheimer’s disease. Similarly, a mealtime intervention to create more uniform lighting and to improve table setting contrast through the use of dark tray liners beneath plates was found to increase oral intake and functional independence. 34 High-contrast manipulations by Dunne et al 37 resulted in an increase in food and liquid intake among persons with severe dementia in the long-term care.

Maximizing Orientation

Challenges in wayfinding (eg, finding the dining room) can be stressful and have particular impact on residents with dementia who have memory loss and cognitive impairment. To make the dining rooms accessible to residents with dementia, the space should be located to minimize the distance traversed by residents from their rooms. 32 Marsden further suggests the dining space be on the path to the central activity area of the care home yet as a side room in order to prevent residents from feeling as though they are “on display” while eating. 38

Sensory cues such as the smell of cooking or baking, the sight of table settings and kitchen items, and the routine dinner music are especially important to remind persons with dementia that it is mealtime and can stimulate appetite. 39 It is also important to reduce competing auditory stimuli such as televisions, radio, and intercoms in order to prevent sensory overload. 40 To reduce spatial disorientation, the dining room should be devoted to food-related activity, the name “dining room” should reflect its function. 41 To facilitate wayfinding, it is important that both the dining room and the dining furniture are permanent in the space. 33 In an effort to provide orientation clues, Nolan and Matthews 42 employed a simple modification consisting of a large clock hung beside a print sign that indicated mealtimes. As residents had been noted to engage in a repetitive pattern of meal-related questioning that often frustrated the nursing staff and other residents, this intervention successfully reduced food-related questions in residents with dementia. Although the reduction in repetitive questions may appear as a staff-centered outcome, it needs to be acknowledged that the clock and the signage were effective aides to support memory and cognitive function of residents, and in turn, to potentially reduce confusion and frustration/agitation in residents. In fact, the study observations found an increase in the number of resident-to-resident interactions, as they were less anxious and confused.

Providing a Sense of Safety and Security

Because a large number of residents use wheelchairs, walkers, and other mobility devices, it is important that the path to the dining room and the space of the dining room accommodate free movement of residents and staff. Medication cart, food cart, dishes cart, garbage, and linen hampers can easily clutter up the dining room and make the navigation among tables unsafe. 43 Zgola and Bordillon 44 suggest residents should be transferred into regular chairs, if possible, to permit better posture at the table and enhance socialization. Although small round tables are noted as being safe to navigate around, 38 square tables with bull nose edges may better divide personal space for dining residents. 14 Furthermore, table legs and height should be considered in their potential to obstruct wheelchairs and chair arms from being pushed in under the table. 14 As Brawley 30 recommends, height-adjustable tables are optimal.

Creating Familiarity and HomeLikeness

Consistently, the evidence indicates that serving food and drinks directly at the table, rather than on trays, provides a more familiar atmosphere for enjoying meals. A comparison of a family-style dining intervention to a preplated dining service demonstrated differences in intake, nutritional risk, fine motor function, and weight. 45 Carrier et al 46 found that institutional food trays posed difficulty in manipulating dishes, lids, and food packages, and therapeutic diets were significantly associated with the risk of malnutrition. A study comparing residents from 45 American facilities demonstrated better food outcomes for both smaller facilities and those with less-institutional features. 47 Similarly, in the study of Desai et al, 22 renovations to the dining room from an institutional appearance to a homelike setting, as well as from tray to family-style foodservice, have been resulted with increased energy intakes. In order to maintain consistency with conventional home layouts, the dining room should be situated near the kitchen. 32 When the decor of the dining environment expresses the cultural preference of the people who use it, it promotes their sense of belonging and their ownership of the room. 36 In the study by Hung, 43 residents with dementia expressed feeling proud and a sense of belonging as they showed off their picture and personal belongings displayed in the dining room.

Providing Optimal Sensory Stimulation

As opposed to large-central dining rooms, several smaller dining spaces for 5 to 12 residents are recommended for more optimal stimulation. 14,32 Studies have demonstrated positive residents’ outcomes (eg, reduced noise, fewer distractions, and more social contact) when residents dined in the smaller dining rooms. 4,48 Noise can be highly distressing to residents and hinders conversations. In a recent study, nurses were able to create a calmer environment by turning off television, CD player, and overhead announcement. 49 Regarding mealtime ambience, music is a widely enjoyed aspect of the sensory environment. Thomas and Smith 50 are among the few to have investigated the relationship between music and food intake among the residents. Their results demonstrated an increase in caloric consumption compared to a dining environment without music. Research also found classical music was effective in reducing aggressive behaviors. 51 –53 Behavioral symptoms such as agitation and restlessness are estimated to affect as many as 93% of the residents with dementia in long-term care. 54,55 Here, behavioral symptoms refer to symptoms of disturbed thought content, mood, or behaviors that frequently occur in residents with dementia. Dementia care experts believe that all behavioral symptoms have meanings, and they are expressions/communications responding to needs that might be related to cognitive or functional or psychiatric reasons. Therefore, environmental interventions that support cognitive and functional abilities or psychosocial needs have potential to treat behavioral symptoms by meeting the underlying needs of the persons with dementia. Moreover, dinner music also seemed to affect the staff members who were observed in paying increased attention toward residents. 51 Nevertheless, Johnson and Taylor 56 note that musical tastes can greatly vary, as the definition of “relaxing music” is largely subjective. It may be difficult for long-term care facilities to accommodate the musical preferences of all residents, where research regarding the impact of music volume during dinner is still required. 56

Providing Opportunities for Social Interaction

In most care home dining rooms, residents are seated according to comparable levels of dependence rather than social compatibility. In a recent study, a group residents with dementia were seated around a rainbow-shaped table and were fed in an assembly line manner. 43 Such setting reflects social disconnection and a (I-It relationship), whereas people with dementia were treated as objects, and feeding was a task to be completed. To create a person-centered environment for dementia care, Geboy 12 has identified 10 design principles for esthetic, functional, and compositional decisions. Among the recommendations, seating is recommended to be at right angles, small groups to stimulate socialization, and the avoidance of periphery furniture arrangements, which hinder both interaction and privacy. A study by Philpin and colleagues 57 draws attention to the impact of spatial surroundings on mealtime social interaction, where a family-style dining environment was key to enhancing both the sociability and a sense of community for persons in the residential care.

Roberts 23 conducted a study to compare a large institutional dining room with a small family-style setting. For the large dining area, organization emphases were placed on safety and protection at mealtimes. With regard to the sensory environment, not only was there excess noise from the kitchen staff but also disruptions from the residents entering and exiting the large space as well as staff conversing among one another from across the room were all observed to have negative impacts on the residents’ socialization. In contrast, the small room hosted only 6 residents for meals, and the room was decorated in home-style decor. Residents were invited to take part in food preparation as well. The more intimate sociophysical environment positively supports social interactions of residents at mealtimes.

Supporting Privacy and Personal Control

The concept “privacy” is important for dining, because it is a personal experience. 44 A resident with dementia is likely to feel overwhelmed sitting with 80 people in a large dining hall. A supportive and flexible environment is particularly important in enabling residents to make use of their abilities and manage at their own choice. In interviews and observations, residents with dementia expressed their need of the choice to eat privately and sit with others for community conversations, while families voiced the need of having a private and comfortable space for them to eat with their loved one. 43

To best emphasize the concept of person-centered care, the Enhanced Dining Program created a pleasant physical environment for mealtimes through renovations that created 3 small dining rooms for 25 to 30 residents. 27 These dining rooms were decorated with homelike items such as paintings, bookshelves, and plants. The tables were set with tablecloths, place mats, tableware, and centerpiece. Appropriate music was played in the background, and aromas of freshly baked bread and brewed coffee greeted the residents as they were invited into the dining room. In addition, the Enhanced Dining Program included a staff education component to encourage verbal cues during meals, evaluations of the residents’ ability to self-feed, and to engage residents in meal preparation activities. The Enhanced Dining Program contributed to significant increases in nutritional intake. 27 Ultimately, the findings of this research underscore both environmental design and staff education in successfully providing person-centered care and enhancing the mealtime experience of residents with dementia. It is evident that both environmental and organizational factors bear influence on the therapeutic potential of dementia care environments.

Discussion

Although research on the effect of physical dining environment on residents’ quality of life in long-term care facilities is developing steadily, it is still in its infancy. Overall, this review confirms that improving the dining experience of residents with dementia is associated with a range of dining room design characteristics, such as small dining rooms, homelike atmosphere, appropriate lighting and color contrast, minimized noise, music, orientation cues, and furniture grouping to foster social interactions. Although the evidence is limited, the existing knowledge has provided support to guide practice and directions for future studies. It is worthwhile to note that, by and large, the empirical studies reviewed here were not theoretically linked or grounded with the guidelines or normative positions espoused in the conceptual literature, such as books by Brawley 30 and Zgola and Bordillon. 44 This is a significant shortcoming of the existing empirical studies in this research area. Theoretical grounding of environmental interventions is an important aspect of advancement of knowledge in a systematic and meaningful way. Future empirical studies would make a stronger contribution if explicit linkage is made between environmental focus of the study (eg, intervention or nonintervention) and design recommendations, guidelines, and/or theoretical positions.

Among the reviewed intervention studies, the most common outcome measures investigated in environmental intervention of dining are behavioral symptoms (6 studies) and calorie intake (6 studies). Arguably, residents with dementia who exhibit behavioral symptoms may simply be responding to something in the environment that is not supportive. Since there are a multitude of symptoms of dementia, research is necessary to find strategies to better support the specific needs of people with dementia (eg, memory decline, cognitive changes, communication difficulties, and functional needs). For example, technological strategies may be used to remind residents with dementia when and where to eat. In consideration of nutritional outcomes, the significance of results was often limited by time factors, since weight, body mass index, and other physiological factors require a longer period of analysis to detect change than was generally conducted.

Meals mean more than absence of malnutrition and behavioral symptoms. 58 However, in our review, 12 of the 22 articles focused on increasing caloric intake and reducing problem behaviors, while only 5 articles looked at the strategies to improve social interactions and relationships. Mealtimes are social events and an opportunity to foster social connectedness (enhancing the I-Thou relationship between residents/coresidents/families/care providers) and promote psychosocial well-being of the residents. Person-centered care is about holistic care, supporting/enabling remained abilities rather than disease/problem focused. Future studies need to examine strategies to improve person-centered care outcomes that include emotional social and spiritual aspects of well-being. Further, Robinson and Gallagher 59 remind us that the baby boomers are a new group of customers that needs to be explored in generating innovative design solutions to meet their diverse dining needs. In addition, residents with dementia represent the primary group of inhabitants in long-term care environments. Providing choice in daily selection and incorporation of a steam table in the dining room influence the quality of food consumed. 60 Having an accurate understanding of their needs, perspective, and experience is crucial to practice development. Engaging more people with dementia to participate in research will be much needed.

Regarding methodological issues, randomized controlled trial is often considered the strongest research design for creating sound scientific knowledge. However, because physical environmental features are inextricably intertwined with the social and interactional context, it is impossible to control confounding variables and separate the independent effect of an environmental change. For instance, the research team of Brush et al 34 experienced a change in staffing policies part way through their study, which undoubtedly affected their findings. On a similar note, in studies that manipulated not only environmental features but also staffing and foodservice such as Desai et al, 22 it is difficult to discern which change had the most or least impact on outcomes of residents with dementia. As much research is needed to support practice change, future inquiries need to employ innovative approaches to address methodological challenges to have a deeper and meaningful understanding of the role of physical environmental aspects of the mealtime setting. Innovative or nontraditional methodological approaches could include mixed methods with quantitative strategies (eg, focusing on caloric intake and level of mealtime assistance) complemented with qualitative methods to have a deeper and nuanced understanding of the psychosocial aspects (eg, emotional aspects of dining and quality of social interaction). Also, action research methods could engage administrators and staff in identifying targeted environmental interventions with selected residents, which in turn, could generate education or practice development tools. The development and use of standardized dining environmental assessment protocol that reflects principles of person-centered care will allow evaluation of the individual facility and comparison across multiple settings as well as facilitate the tracking of progress.

Currently, most intervention studies have small sample sizes, lack comparison groups or utilizing nonequivalent groups, and homogenous participant samples (often, caucasian and female), thereby limiting the generalizability of the research results. In some studies, 23,27,52 only a single mealtime was evaluated that can undermine the effect of the intervention under study.

In addition, the relationships between environmental design features that respond to cultural preference/ethnic tradition and dining experience of residents are missing in the existing literature. In our review, only 2 studies considered the mealtime experience of immigrant seniors with dementia, 19,61 while none focused on the dining environment for ethnic minorities in long-term care. Clearly, more research is required on cultural and ethnic aspect to make the dining environment responsive to needs of culturally diverse population.

Finally, person-centered care is about meeting the unique individual needs of resident. Making appropriate environmental modifications to support individual resident’s routine, preference, and needs is essential to honor the residents’ identity, support their quality of life, and well-being. Thoughtfully designed environments represent valuable therapeutic resource in the care of residents with dementia. Positive dining experiences for residents are a area reflection of the care that is aligned with person-centered care principles, emphasizing on supporting abilities and promoting connectedness. This experience includes being able to find the dining room, being able to engage in social interactions, and being able to respond to familiar and manageable stimulations. 58 The physical environmental features of dining rooms can play an important role, yet underutilized resource, on positive outcomes of the dining experience among residents with dementia in long-term care facilities.

Conclusion

In recent years, there is a growing recognition of the role of environment design in dining spaces to support culture change in long-term care. Facility administrators are faced with important decisions about how residents’ mealtime experience can be enhanced based on the evidence available. It is clear from this review that there is a growing body of research to support the importance of certain physical environmental features in the dining context that can foster positive resident outcomes. The evidence indicates that well-designed physical settings play an important role in creating a person-centered dining environment to support best possible mealtime experience of residents. Care facility administrators and facility designers would be served well in their decision making to take into consideration the benefits of environmental modifications, along with changes in mealtime practices, staffing, or organizational changes that might be considered. Physical environment plays an integral role in any meaningful person-centered care philosophy and practice. This review has identified key environmental aspects of the dining rooms in long-term care and linked them with the best practice concept person-centered care.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a research grant from the CapitalCare Foundation, Edmonton, Canada.

References

- 1. Kitwood TM. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buber M. Dialogue: In Between Man and Man. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brooker D. Person-centered Dementia Care: Making Services Better. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hung L, Chaudhury H. Exploring personhood in dining experiences of residents with dementia in long-term care facilities. J Aging Stud. 2011;25(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alzheimer Society of Canada. Rising tide: the impact of dementia on Canadian society. http://www.alzheimer.ca/en/Get-involved/Raise-your-voice/Rising-Tide. Accessed January 27, 2013.

- 6. Pioneer Network. Promising practices in dining. http://www.pioneernetwork.net/Providers/PromisingPractices/Dining/. Accessed January 27, 2013.

- 7. Calkins C. Design for Dementia: Planning Environments for the Elderly and the Confused. Owings Mills, MD: National Health Publishing; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen U, Weisman G. Holding on to Home. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Day K, Carreon D, Stump C. The therapeutic design of environments for people with dementia: a review of the empirical research. Gerontologist. 2000;40(4):397–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Verbeek H, Rossum E, Zwakhalen SM, Kempen GI, Hamers JP. Small, homelike care environments for older people with dementia: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(2):252–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fleming R, Purandare N. Long-term care for people with dementia: environmental design guidelines. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(7):1084–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geboy L. Linking person-centered care and the physical environment: 10 design principles for elder and dementia care staff. Alzheimer’s Care Today. 2009;10(4):228–231. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geboy L, Meyer-Arnold B. Person-centered Care in Practice: Tools for Transformation. Verona, WI: Attainment Company Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Briller SH, Proffitt MA, Perez K, Calkins MP, Marsden JP. Maximizing cognitive and functional abilities. In: Calkins MP, ed. Creating Successful Dementia Care Settings. Vol. 2. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Venturato L. Dignity, dining, and dialogue: reviewing the literature on quality of life for people with dementia. Int J Older People Nurs. 2010;5(3):228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Evans BC, Crogan NL, Shultz JA. The meaning of mealtimes: connection to the social world of the nursing home. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31(2):11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Genoe R, Dupuis SL, Keller HH, Schindel Martin L, Cassolato C, Edward HG. Honouring identity through mealtimes in families living with dementia. J Aging Stud. 2010;24(3):181–193. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Keller HH, Schindel Martin L, Dupuis S, Genoe R, Edward HG, Cassolato C. Mealtimes and being connected in the community-based dementia context. Dementia, 2010;9(2):191–213. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lam IT, Keller H. Honoring identity through mealtimes in Chinese Canadian immigrants [published online June 12, 2012]. Am J Alzheimer Dis Other Demen. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Hoof J, Kort HSM, van Waarde H, Blom MM. Environmental interventions and the design of homes for older adults with dementia: an overview. Am J Alzheimer Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(3):202–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crogan NL, Evans B, Severtsen B, Shultz JA. Improving nursing home food service: uncovering the meaning of food through residents’ stories. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;30(2):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Desai J, Winter A, Young KW, Greenwood CE. Changes in type of foodservice and dining room environment preferentially benefit institutionalized seniors with low body mass indexes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(5):808–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roberts E. Six for lunch: a dining option for residents with dementia in a special care unit. J Hous Elderly. 2011;25(4):352–379. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shatenstein B, Ferland G. Absence of nutritional or clinical consequences of decentralized bulk food portioning in elderly nursing home residents with dementia in Montreal. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(11):1354–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. West GE, Ouellet D, Ouellette S. Resident and staff ratings of foodservices in long-term care: implications for autonomy and quality of life. J Appl Gerontol. 2003;22(1):57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ministry of Health and Long-term care. People caring for people: impacting the quality of life and care of residents of long-term care homes—a report of the independent review of staffing and care standards for long-term care homes in Ontario. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/pub/ministry_reports/staff_care_standards/staff_care_standards.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2013.

- 27. Perivolaris A, LeClerc CM, Wilkinson K, Buchanan S. An enhanced dining program for persons with dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Q. 2006;7(4):258–267. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Regnier V. Design for Assisted Living: Guidelines for Housing the Physically and Mentally Frail. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zeisel J. Life quality Alzheimer’s care in assisted living. In: Schwarz B., Brent R., eds. Aging, Autonomy and Architecture: Advances in Assisted Living. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brawley EC. Design innovations for aging and Alzheimer’s: creating caring environments. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cluff PJ. Alzheimer’s disease and the institution: issues in environmental design. Am J Alzheimer Dis Other Demen. 1990;5(3):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Calkins MP. Dining room design. In: Dementia Design Info. https://www4.uwm.edu/dementiadesigninfo/data/white_papers/Dining%20Room%20Design.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2013.

- 33. Weisman GD, Lawton MP, Calkins Norris-Baker L, Sloane P. Professional environmental assessment protocol. Unpublished manuscript. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brush JA, Meehan RA, Calkins MP. Using the environment to improve intake for people with dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Q. 2002;3(4):330–338. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Illuminating Engineering Society of North America (IES). Recommended Practice for Lighting and the Visual Environment for Senior Living [Report]. New York, IES. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDaniel JH, Hunt A, Hackes B, Pope JF. Impact of dining room environment on nutritional intake of Alzheimer’s residents: a case study. Am J Alzheimer Dis Other Demen. 2001;16(5):297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dunne TE, Neargarder SA, Cipolloni PB, Cronin-Golomb A. Visual contrast enhances food and liquid intake in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Nutr. 2004;23(4):533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marsden JP. Humanistic Design of Assisted Living. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berg G. The Importance of Food and Mealtimes in Dementia Care. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Butterfield Whitcomb J. The way to go home: therapeutic music and milieu. Act Dir Q. 2000;1(1):33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Passini R, Pigot H, Rainville C, Tetrault M. Wayfinding in a nursing home for advanced dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Environ Behav. 2000;32(5):684–710. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nolan BA, Mathews RM. Facilitating resident information seeking regarding meals in a special care unit: an environmental design intervention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;30(10):12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hung L. The dining experience of persons with dementia [Master’s thesis]. http://www.sfu.ca/uploads/page/27/thesis_hung.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2013.

- 44. Zgola J, Bordillon G. Bon Appétit: The Joy of Dining in Long-Term Care. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nijs KA, de Graaf C, Kok FJ, van Staveren WA. Effect of family style mealtimes on quality of life, physical performance, and body weight of nursing home residents: cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7551):1180–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carrier N, West GE, Ouellet D. Cognitively impaired residents' risk of malnutrition is influenced by foodservice factors in long-term care. J Nutr Elder. 2006;25(3-4):73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reed PS, Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Williams CS, Boustani M. Characteristics associated with low food and fluid intake in long-term care residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schwarz B, Chaudhury H, Tofle RB. Effect of design interventions on dementia care setting. Am J Alzheimer Dis Other Demen. 2004;19(3):172–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ullrich S, McCutcheon H, Parker B. Reclaiming time for nursing practice in nutritional care: outcomes of implementing Protected Mealtimes in a residential aged care setting. J Clinical Nurs. 2011;20(9-10):1339–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thomas DW, Smith M. The effect of music on caloric consumption among nursing home residents with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Activities Adaptation Aging. 2009;33(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ragneskog H, Kihlgren M, Karlsson I, Norberg A. Dinner music for demented patients: Analysis of video-recorded observations. Clin Nurs Res. 1996;5(3):262–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Denney A. Quiet music: an intervention for mealtime agitation? J Gerontol Nurs. 1997;23(7):6–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hicks-Moore SL. Relaxing music at mealtimes in nursing homes: effects on agitated patients with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31(12):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gruber-Baldini AL, Boustani M, Sloane PD, Zimmerman S. Behavioral symptoms in residential care/assisted living facilities: prevalence, risk factors, and medication management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(10):1610–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Barrick AL, Sloane PD, Williams CS, et al. Impact of ambient bright light on agitation in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(10):1013–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Johnson R, Taylor C. Can playing pre-recorded music at mealtimes reduce the symptoms of agitation for people with dementia? Int J Ther Rehab. 2011;18(12):700–708. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Philpin S, Merrell J, Warring J, Gregory V, Hobby D. Sociocultural context of nutrition in care homes. Nurs Older People. 2011;23(4):24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hellen C. Doing lunch: a proposal for a functional well-being assessment. Alzheimer Care Q. 2002:3(4):302–315. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Robinson GE, Gallagher A. Culture change impacts quality of life for nursing home residents. Top Clin Nutr. 2008;23(2):120–130. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Crogan NL, Short R, Dupler AE, Heaton G. The influence of cognitive status on elder food choice and meal service satisfaction [published online October 3, 2012]. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Dement. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu S, Barker JC. Hot tea and juk: the institutional meaning of food for Chinese elders in an American nursing home. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(11):46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]