Abstract

Objective:

The need for assistance from others is a hallmark concern in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The psychometric properties of the Dependence Scale (DS) for measuring treatment benefit were investigated in large randomized clinical trials of patients with mild to moderate AD.

Methods:

Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the DS were examined. Path models appraised relationships and distinctiveness of key AD measures. The responder definition was empirically derived.

Results:

Generally acceptable reliability (α ≥ .65), significant (P < .001) known-groups tests, and moderate to strong correlations (r ≥ .31) confirmed the DS psychometric properties. Path models supported relationships and distinctiveness of key AD measures. A DS change of ≤1 point for patients with limited home care and ≤2 points for patients with assisted living care best described stability of the level of dependence on caregivers.

Conclusion:

The DS is a psychometrically robust measure in mild to moderate AD. The empirically derived responder definition aids in the interpretation of DS change.

Keywords: dependence, Alzheimer’s disease, caregiver, psychometric properties, responder definition, interpretation

Introduction

The increasing need for assistance from others is a burdensome and costly challenge for patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and their caregivers. The Dependence Scale (DS) was originally developed to capture the caregiver’s assessment of the required amount of assistance needed by patients with a diagnosis of AD. 1 Prior investigations into the measurement properties using data in smaller nonrandomized studies (n < 500) empirically support the use of the DS to appraise dependence in mild to severe AD. 1 –3 In addition, qualitative investigations by Frank and colleagues 4 among clinicians, caregivers, and patients with AD support the content validity of the DS in mild to moderate AD. However, for the DS to be deemed appropriate for the purpose of assessing the treatment benefit of pharmacologic interventions in large randomized clinical trials (RCTs), additional investigation to support the psychometric properties of the instrument and its ability to detect clinically meaningful change is needed.

The primary objective of study ELN115727-301 and study ELN115727-302 (hereafter referred to as study 301 and study 302, respectively) was to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of multiple doses of intravenously (IV) administered bapineuzumab in patients with mild to moderate AD compared to placebo. 5 Although both of these studies failed to meet the coprimary efficacy end points of change from baseline to Week 78 on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) and Disability Assessment Scale for Dementia (DAD), data from these large studies provide the opportunity to evaluate the DS in this context of use as well as document the psychometric properties of the DS, a key secondary end point in both of these RCTs.

Therefore, the primary objective of this investigation was to demonstrate the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the DS in large RCTs of patients with mild to moderate AD. In addition, path models of the hypothesized relationship between the studies’ measures of behavior (Neuropsychiatric Inventory [NPI]), cognition (ADAS-cog), functioning (DAD), and dependence (DS) appraised the distinctiveness of each measure as well as further demonstrating the strength of these relationships. Finally, the most appropriate responder definition for the DS among patients with mild to moderate AD was empirically derived using these data to assist in the interpretation of DS score changes over time. The resulting information from these analyses provide additional information for researchers when evaluating the utility of the DS for use in future studies of patients with mild to moderate AD.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Populations With AD

Study 301 and Study 302 were multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group outpatient studies in male and female patients aged 50 to <89 years with mild to moderate AD. 5 Study 301 included participants from the United States and Canada who were apolipoprotein E (APOE) ∊4 allele noncarriers, and Study 302 included participants from the United States who carried the APOE ∊4 allele, a genetic risk factor for AD. 6 Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are described elsewhere. 5 Bapineuzumab or placebo was administered via an IV infusion every 13 weeks for a total of 6 infusions over the course of the 78-week study. The blinded efficacy and safety evaluation visits at baseline (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] at screening) and Week 78 (end of study) were included in this cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation of the DS as well as other well-established and validated measures used frequently in clinical trials of AD.

Measures

Dependence Scale

The full DS is comprised of 2 parts; Part I is used in outcomes assessments (hereafter referred to as the DS total score) and has 13 items. 1 The first 2 DS items measure (A) need for reminders or advice to manage and (B) help remembering important things; these have 3 response options (no, occasionally, or frequently). The response scale for the remaining 11 items (C–M), ranging from the need for frequent help finding misplaced objects, and so on to the need to be tube fed, have no or yes response options. 1 The DS was designed to be administered by a trained interviewer to a caregiver of a person with AD.

Part II of the full DS evaluates the patient with AD using the Equivalent Institutional Care (EIC) with 3 response levels: limited home care, adult home/assisted living, and health-related facility. The interviewer administering Part I completes Part II based on the interview and knowledge of the care the patient receives. It is important to note that the EIC response selections refers to the level of care required, not necessarily to the actual placement, as some patients may receive around the clock nursing care associated with a health-related facility at home. The psychometric performance of Part II is not addressed in this article, as Part II is intended to provide adjunctive information to the information obtained in Part I. However, Part II responses assisted in the psychometric tests evaluating known-groups validity and served as an anchor for assessing the responder definition.

The DS total score is calculated by summing the scores of all 13 items (items A through M) from Part I. Items A and B are coded as follows: no = 0; occasionally = 1; and frequently = 2. Items C through M are coded as no = 0 and yes = 1. The range of the DS total score is 0 to 15, where higher DS total scores indicate worse impairment.

Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale: Cognitive subscale, 11-item version

The ADAS-cog is a global cognitive measure determined by summing the scores from 11 items, ranging from word recall through comprehension of spoken language. 7 The ADAS-cog total score ranges from 0 to 70, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive impairment.

Disability Assessment for Dementia

The DAD administered to the patient’s caregiver as an interview measures instrumental and basic activities of daily living in patients with AD. The patient’s initiation, planning and organization, and effectiveness of performance on basic activities of daily living are evaluated in 10 areas, ranging from hygiene through leisure and housework. 8 The DAD total score ranges from 0 to 100 and higher scores indicate better functioning.

Clinical Dementia Rating Scale sum of boxes

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) is a global clinical staging instrument based on 6 clinical ratings, ranging from memory through personal care. 9 The CDR interview includes discussions with the patient and caregiver using a structured format. Each component is scored as 0 (normal), 0.5 (questionable), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe), with the exception of personal care, which does not have a 0.5 outcome. With each component score placed in a box, the CDR scale sum of boxes (CDR-SB) total score is the sum of the 6 ratings and ranges from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating more impairment.

Mini-Mental State Examination

The MMSE consists of 5 components: orientation to time and place, registration of 3 words, attention and calculation, recall of 3 words, and language. 10 The MMSE total score ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better mental status.

Neuropsychiatric inventory

The NPI assesses psychopathology in patients with dementia by evaluating 12 neuropsychiatric domains common in dementia, ranging from delusions to appetite/eating behaviors and is administered to the patient’s caregiver. 11 The NPI total score ranges from 0 to 144 and higher NPI total scores indicate worse impairment.

Resource Utilization in Dementia version 2.4 Caregiver Time

The Resource Utilization in Dementia version 2.4 (RUD-Lite v2.4) assesses several domains of care, such as caregiver time and health care utilization. Total Caregiver Time per Month, which assesses the hours the caregiver has spent assisting the patient, was used in these analyses. 12

Statistical Analyses

Analysis population

The data in the psychometric analyses come from the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) populations from Study 301 and Study 302, defined as all randomized patients who received at least 1 infusion or portion of an infusion of study drug or placebo and who had a baseline and at least 1 postbaseline assessment of the ADAS-cog and DAD. In addition, this analysis was limited to patients with a DS total score at baseline. All analyses were conducted in 3 blinded data sets: within each of the 2 study data sets separately and then in the larger pooled data set combining the data of Study 301 and Study 302.

Item analysis

Analyses of the percentage endorsing each DS item were conducted for the baseline and Week 78 data in each of the data sets. In addition, Rasch analyses examining individual item fit, overall model fit, and the Rasch reliability estimates were conducted for each of the 3 data sets. Full description of the Rasch analyses methods for each of the 3 data sets are described in the Supplement present at journal’s web site, along with the article (http://aja.sagepub.com).

Internal consistency reliability

Internal consistency reliability addresses the extent to which individual items in the instrument are related to one another. Although the 13 items on the DS measure increasing need for assistance and, therefore, are not necessarily related to each other as they progress, prior psychometric assessments of the DS have incorporated Cronbach’s α as the appropriate measure of internal consistency, with results of α ≥.66 1 –3 “indicating acceptable internal consistency for the scale as a whole.” 1 In keeping with these results, Cronbach’s α ≥.66 signified the acceptable internal consistency expected in all baseline and Week 78 data sets.

Known-groups validity

Known-groups validity is the extent to which scores from an instrument are different for groups of participants that differ on a relevant indicator. Tests using analysis of variance were conducted at baseline comparing DS mean scales scores by the EIC status and MMSE score categorizations, with mild dementia defined as MMSE ≥21 and moderate dementia defined as MMSE ≤20. Prior studies investigating EIC and MMSE-created groups have demonstrated important mean DS differences of ∼2 to 3 more points for each progressively more extensive care setting and ∼1 to 2 point differences in MMSE-defined groups. 2,3 Based on these prior studies, it was hypothesized that the DS would show similar patterns of increasing dependence for each progressively more extensive care setting.

Construct validity

Convergent validity

Convergent validity involves demonstrating that different measures of the same construct substantially correlate. Pearson correlation coefficients examined the convergent validity of the DS total score with scores from the ADAS-cog, DAD, CDR-SB, MMSE, NPI, and the RUD-Lite v2.4 Caregiver Time outcomes at baseline and at Week 78. Prior investigations of the DS relationship with these AD measures have shown the strongest DS association with the DAD, with Pearson correlations (r) ranging from −.72 to −.89. 2,3,13 –15 The DS–MMSE correlation has also been reported as robust, with r ranging from −.37 16 in a study of 172 probable patients with AD and their caregivers to −.76 in a phase 2 AN1792 study. 3 As measures of cognition, the ADAS-cog and CDR-SB have consistently demonstrated a moderate to strong relationship with the DS (ADAS-cog: 0.42 ≤ r ≤ .70; CDR-SB: 0.64 ≤ r ≤ .84). 2,3,14 Behavior, as measured by the NPI, had a weak relationship with the DS (r = .21) in the Dependence in Alzheimer’s Disease in England study when examined in 172 patients with mild, moderate, and moderately severe AD 2 but a much stronger relationship (r = .66) with the 2009 Enhancing Care in Alzheimer’s Disease (ECAD) study of 100 patients with probable or possible AD or mild cognitive impairment. 13 The ECAD study also found a strong correlation between the RUD-Lite v2.4 Caregiver Time and dependence (r = .66). 13

Based on these known studies of the construct validity of the DS, it was hypothesized that the DS would continue to demonstrate a strong (r ≥ |.60|) negative relationship with the DAD and positive relationship with the CDR-SB (positive r) and a moderate (|.30| < r < |.60|) relationship with the ADAS-cog (positive r), MMSE (negative r), and Caregiver Time (positive r). A moderate positive relationship with the NPI was also predicted among the patients with mild and moderate AD in these data sets.

Responsiveness: Ability to detect change over time

Responsiveness refers to the extent to which the instrument can detect true change in participants known to have changed in clinical status. 17 This ability to detect change was examined using Pearson correlations of DS change scores between baseline and week 78 and change scores over the same period from the ADAS-cog, DAD, CDR-SB, MMSE, NPI, and the RUD-Lite v2.4 Caregiver Time outcomes. Prior reports of change score correlations for these measures with the DS over an 18-month time span is limited to the MMSE, where r = −.42. 2 It was hypothesized that all change score correlations would be moderate in magnitude, with the exception of the NPI, where the change score correlation would be weak based on predicted moderate NPI cross-sectional relationships.

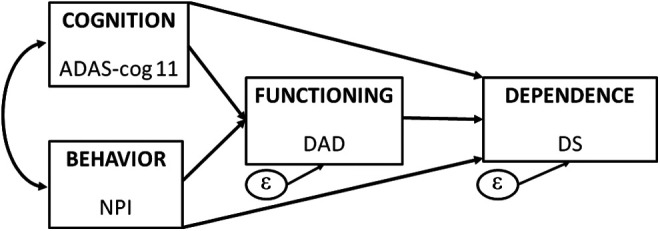

Path analyses

The path model depicted in Figure 1 emphasizes the theoretical importance of cognition, functioning, and behavior as predictors of dependence in a simplified model consistent with several models of dependence in AD previously put forward. 2,16,18 –20 This fully saturated model posits that cognition and behavior are direct predictors of dependence and also that cognition and behavior each relates to functioning, which is also a direct predictor of dependence. This model was tested to empirically evaluate these relationships, further support the construct validity of the DS, and discern the distinctiveness of these important end points in AD. Given the multidimensional nature of AD, these data will aid in establishing the incremental value of the DS in studies that include measures of cognition, behavior, and functioning. All estimated standardized path coefficients, P values, and explained variances were examined in the baseline and Week 78 data. Based on prior tests of this model, 2 stronger relationships between the model components were predicted at week 78 compared to baseline as AD progressed.

Figure 1.

Path model for hypothesized relationships between key Alzheimer’s disease (AD) constructs measured by their respective scale scores.

Responder definition

Mean change scores

Using the Predictors Study 1,16 data, responders with mild to moderate AD at baseline who demonstrating stability in their care setting over 18 months had, on average, up to a 1-point change in their DS scores. 2,3 The 3 data sets provided the opportunity to confirm the responder definition for the DS over 18 months (DS score change ≤ 1) in the populations with general AD and mild to moderate AD 21 and to explore the impact that the severity of the disease process may have on the responder definition.

Mean change scores from baseline to Week 78 for the DS were calculated by baseline to Week 78 EIC residential change status (eg, limited home care at baseline to adult home/assisted living at Week 78, and so on). Within each baseline starting category of change (limited home, adult home/assisted living, or health-related facility), mean change scores for the patients who remain stable over the 18-month time span were compared to the mean change scores of those who decline in EIC setting using Dunnett’s test. 22 An examination of the trend of the mean change scores when sample sizes were small (<30) was also computed. In addition, the responder definition analysis was conducted in separate subgroups of patients with mild and moderate AD using baseline MMSE scores (mild [MMSE ≥ 21]; moderate [MMSE ≤ 20]) to examine the appropriateness of the responder definition in each of these 2 severity subgroups.

Receiver–operating characteristic analyses

In addition to averaging patients’ change scores from baseline to Week 78 within the corresponding EIC change categories, a receiver–operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was executed to confirm the best DS change score cutoff point for discerning patients within each EIC change category using the power of the pooled studies data set. A key advantage of the ROC method is that the results reflect actual change scores (ie, integers) that individual patients attain over time rather than mean values.

For the ROC curve analyses, the sensitivity and specificity of possible change score cutoff points (0 through 5) were calculated to evaluate classifying patients at or above each specific level for stability (limited home and adult home/assisted living) versus a decline in care setting over 18 months. Assuming equal importance of sensitivity and specificity, these 2 parameters were jointly optimized by selecting the change score value with the lowest Youden index score. 23 The ROC curves were also created using standard plotting methods, 24 and the area under the curve (AUC), reported as the c-statistic, provided an indication of the total overall association between the DS change scores and EIC change categories used to construct the specific curve. The AUC values near 0.5 indicate discrimination no better than chance, while values close to 0.90 signify excellent discrimination, with 0.70 as a lower bound for acceptable discrimination. 25 The ROC analyses were conducted across all patients and then again separately among subsets of patients who have mild AD at baseline (MMSE ≥ 21) and those who have moderate AD at baseline (MMSE ≤ 20).

Results

Participant Populations With AD

Table 1 details the characteristics at baseline of the patients with AD in the mITT data sets with baseline DS scores. The mean age was similar in both studies (72.8 vs 72.1 years), but there were more in the oldest subgroup of octogenarians (30% vs 19%) and fewer patients with AD in the 70 to 79 years old age span (36% vs 47%) in study 301 than in study 302. Most participants were white (∼95%) and female (53%-55%). A greater percentage of study 301 patients had mild AD (57% vs 51%); however, with the exception of APOE ∊4 status, other characteristics were generally similar between the patients of the 2 studies at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in Study 301, Study 302, and the Pooled Study 301 and 302 Data.

| Characteristics | Study 301 (N = 1245) | Study 302 (N = 1089) | Pooled 301 and 302 (N = 2334) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), yrs | 72.8 (9.6) | 72.1 (8.2) | 72.5 (9.0) |

| 50-59 yrs, n (%) | 160 (12.9) | 94 (8.6) | 254 (10.9) |

| 60-69 yrs, n (%) | 271 (21.8) | 280 (25.7) | 551 (23.6) |

| 70-79 yrs, n (%) | 442 (35.5) | 508 (46.6) | 950 (40.7) |

| 80-89 yrs, n (%) | 372 (29.9) | 207 (19.0) | 579 (24.8) |

| Female n (%) | 662 (53.2) | 599 (55.0) | 1261 (54.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 1182 (94.9) | 1043 (95.8) | 2225 (95.3) |

| Black or African American | 31 (2.5) | 32 (2.9) | 63 (2.7) |

| Asian | 11 (0.9) | 5 (0.5) | 16 (0.7) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | |

| Other | 19 (1.5) | 6 (0.6) | 25 (1.1) |

| Duration of AD, mean (SD), yrs | 3.1 (2.3) | 3.4 (2.4) | 3.2 (2.4) |

| APOE*∊4 allele copy number, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 1245 (100.0) | – | 1245 (53.3) |

| 1 | – | 819 (75.2) | 819 (35.1) |

| 2 | – | 270 (24.8) | 270 (11.6) |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 21.2 (3.2) | 20.7 (3.2) | 21.0 (3.2) |

| Mild ≥ 21, n (%) | 713 (57.3) | 554 (50.9) | 1267 (54.3) |

| Moderate ≤ 20, n (%) | 532 (42.7) | 535 (49.1) | 1067 (45.7) |

| ADAS-cog, mean (SD) | 22.3 (9.8) | 23.7 (9.5) | 22.9 (9.7) |

| DAD, mean (SD) | 80.0 (18.9) | 80.3 (18.0) | 80.1 (18.5) |

| DS, mean (SD) | 4.6 (2.2) | 4.8 (2.0) | 4.7 (2.2) |

| CDR-SB, mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.9) | 5.2 (2.7) | 5.2 (2.8) |

| NPI, mean (SD) | 11.0 (12.4) | 10.1 (11.8) | 10.6 (12.1) |

| RUD-Lite v2.4 Total Caregiver Time, mean (SD) | 126.3 (183.0) | 122.1 (184.7) | 124.4 (183.8) |

| Equivalent Institutional Care (EIC), n (%) | |||

| Limited home care | 1012 (81.3) | 877 (80.5) | 1889 (80.9) |

| Adult home | 223 (17.9) | 202 (18.5) | 425 (18.2) |

| Health-related facility | 7 (0.6) | 6 (0.6) | 13 (0.6) |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 7 (0.3) |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Cognitive subscale; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating scale sum of boxes; DAD, Disability Assessment Scale for Dementia; DS, Dependence Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; RUD-Lite v2.4, Resource Utilization in Dementia version 2.4; SD, standard deviation.

Item Analyses

The endorsement of DS items in the 3 data sets at baseline and Week 78 is provided in Table 2. At baseline, most caregivers endorsed either occasionally or frequently as a response option for items A and B (memory on daily tasks and important things), and only 11% to 39% endorsed items D to F (eg, needs frequent help, needs to be watched, and so on). Less than 7% of caregivers endorsed items G to L (eg, needs to be fed, taken to the toilet, and so on) with no endorsement of item M (tube fed) at baseline. At Week 78, all items generally exhibited an increase in endorsement. More caregivers selected the frequently over the occasionally option for items A and B and endorsement of items D to F increased from 23% to 58%. Items G to L were endorsed by less than 20% and a few caregivers (<1%) endorsed item M.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of DS Items Endorsement at Baseline in Study 301, Study 302, and the Pooled Data at Baseline and Week 78.

| DS Item and Description | Baseline | Week 78 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 301 (N = 1245), n (%) | Study 302 (N = 1089), n (%) | Pooled 301 and 302 (N = 2334), n (%) | Study 301 (N = 953) | Study 302 (N = 854) | Pooled 301 and 302 (N = 1807) | |

| A. Daily task | ||||||

| Occasionally | 275 (22.1) | 241 (22.1) | 516 (22.1) | 149 (15.6) | 126 (14.8) | 275 (15.2) |

| Frequently | 700 (56.2) | 652 (59.9) | 1352 (57.9) | 639 (67.1) | 608 (71.2) | 1247 (69.0) |

| B. Important things | ||||||

| Occasionally | 345 (27.7) | 239 (21.9) | 584 (25.0) | 163 (17.1) | 140 (16.4) | 303 (16.8) |

| Frequently | 776 (62.3) | 788 (72.4) | 1564 (67.0) | 716 (75.1) | 673 (78.8) | 1389 (76.9) |

| C. Frequent help | 1046 (84.0) | 965 (88.6) | 2011 (86.2) | 840 (88.1) | 778 (91.1) | 1618 (89.5) |

| D. Household chores | 489 (39.3) | 408 (37.5) | 897 (38.4) | 552 (57.9) | 482 (56.4) | 1034 (57.2) |

| E. Be watched or kept company | 134 (10.8) | 126 (11.6) | 260 (11.1) | 223 (23.4) | 236 (27.6) | 459 (25.4) |

| F. Be escorted | 269 (21.6) | 214 (19.7) | 483 (20.7) | 340 (35.7) | 314 (36.8) | 654 (36.2) |

| G. Be accompanied bathing/eating | 77 (6.2) | 47 (4.3) | 124 (5.3) | 173 (18.2) | 169 (19.8) | 342 (18.9) |

| H. Be dressed/washed/groomed | 59 (4.7) | 30 (2.8) | 89 (3.8) | 146 (15.3) | 129 (15.1) | 275 (15.2) |

| I. Taken to the toilet | 19 (1.5) | 8 (0.7) | 27 (1.2) | 69 (7.2) | 64 (7.5) | 133 (7.4) |

| J. Be fed | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.5) | 6 (0.3) | 13 (1.4) | 12 (1.4) | 25 (1.4) |

| K. Be turned/moved | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 12 (1.3) | 7 (0.8) | 19 (1.1) |

| L. Wear diaper/catheter | 58 (4.7) | 29 (2.7) | 87 (3.7) | 110 (11.5) | 80 (9.4) | 190 (10.5) |

| M. Be tube fed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.7) | 9 (0.5) |

Abbreviation: DS, Dependence Scale.

The results and discussion of the Rasch analyses for each of the 3 data sets are available in the Supplement present at journal’s web site, along with the article (http://aja.sagepub.com). Overall, the model demonstrated adequate performance, although there were similar response thresholds for item A, low person separation indices (≤0.74), and an item imbalance at baseline (many items measuring higher levels of dependence among the patients with mild to moderate AD).

Internal Consistency Reliability

The Cronbach’s α estimates for internal consistency at baseline were .67, .65, and .66 for Study 301, Study 302, and the pooled data, respectively. At Week 78, α = .79 in all 3 data sets. This improved assessment of internal consistency is consistent with the increase in item endorsement at Week 78 shown in Table 2.

Known-Groups Validity

Known-groups validity was demonstrated across all 3 data sets at baseline. Statistically significant (P < .0001) overall and pairwise comparisons were observed for mean DS total scores classified by: 1) EIC status, with >2-point differences between adjacent classifications, 2) and by MMSE cut points (mild, MMSE ≥ 21; moderate, MMSE ≤ 20) where there was a 1.1 to 1.3-point difference (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Mean DS Scores Within Equivalent Institutional Care Status and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) Severity Groups in Study 301, Study 302, and Pooled Data at Baseline.

| EIC Comparison | Limited Home Care, Mean (n, SE) | Adult Home/Assisted Living, Mean (n, SE) | Health-Related Facility, Mean (n, SE) | P Value for Overall Comparisona | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 301 | 4.2 (1012, 2.0) | 6.4 (223, 2.1) | 9.0 (7, 1.8) | <.0001b,c,d | |

| Study 302 | 4.3 (877, 1.8) | 6.5 (202, 1.9) | 8.7 (6, 1.2) | <.0001b,c,d | |

| Pooled 301 and 302 | 4.3 (1889, 2.0) | 6.4 (425, 2.0) | 8.8 (13, 1.5) | <.0001b,c,d | |

| MMSE Categories | Mild, MMSE ≥ 21, Mean (n, SE) | Moderate, MMSE ≤ 20, Mean (n, SE) | P Value for Overall Comparisona | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 301 | 4.0 (713, 2.1) | 5.3 (532, 2.2) | <.0001 | ||

| Study 302 | 4.2 (554, 1.9) | 5.3 (535, 2.0) | <.0001 | ||

| Pooled 301 and 302 | 4.1 (1267, 2.0) | 5.3 (1067, 2.1) | <.0001 | ||

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; DS, Dependence Scale; EIC, Equivalent Institutional Care; SE, standard error.

a P value for overall comparison using ANOVA.

b P < .0001 for limited home care versus adult home/assisted living care.

c P < .0001 for limited home care versus health-related facility.

d P < .0001 for adult home/assisted living care versus health-related facility.

Construct Validity

Convergent validity

Convergent validity, expressed through a pattern of moderate to strong correlations between the DS and measures of cognition (ADAS-cog, MMSE), functioning (DAD), dementia severity (CDR-SB), behavior (NPI), and Caregiver Time (RUD-Lite) at baseline and at the end of the study, is demonstrated in Table 4 and was consistent with prior studies. 2,3,13,14,16,19 With the exception of the relationship with the NPI, which remained moderate, all coefficients for other measures of correlation were strong (r ≥ |.60|) at Week 78.

Table 4.

Pearson Correlations Between the DS and Other PRO Study Measures in Study 301, Study 302, and Pooled Data at Baseline, Week 78, and Change From Baseline to Week 78.a

| PRO Study Measure | Study 301 | Study 302 | Pooled 301 and 302 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 78 | Change | Baseline | Week 78 | Change | Baseline | Week 78 | Change | |

| ADAS-cog | 0.36 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.40 |

| DAD | −0.64 | −0.79 | −0.51 | −0.62 | −0.55 | −0.51 | −0.63 | −0.79 | −0.51 |

| CDR-SB | 0.62 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.48 |

| MMSE | −0.35 | −0.60 | −0.46 | −0.32 | −0.62 | −0.43 | −0.34 | −0.61 | −0.45 |

| NPI | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.26 |

| RUD-Lite v2.4 Primary Caregiver Time | 0.51 | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.40 |

Abbreviations: ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—Cognitive subscale; CDR-SB, clinical dementia rating scale sum of boxes; DAD, Disability Assessment Scale for Dementia; DS, Dependence Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; RUD-Lite v2.4, Resource Utilization in Dementia version 2.4.

a P < .0001 for all correlations.

Responsiveness: Ability to detect change

The change score correlations between the DS change scores from baseline to Week 78 and respective change scores for the ADAS-cog, DAD, CDR-SB, MMSE, and RUD-Lite Primary Caregiver Time scales were moderate or strong in magnitude (Table 4), with all correlations statistically significant (P < .0001). These moderate to strong correlations between the DS change scores and other previously accepted measures of therapeutic change, such as the ADAS-cog, confirmed that the DS is a sensitive measure for detecting clinically relevant change.

Path models

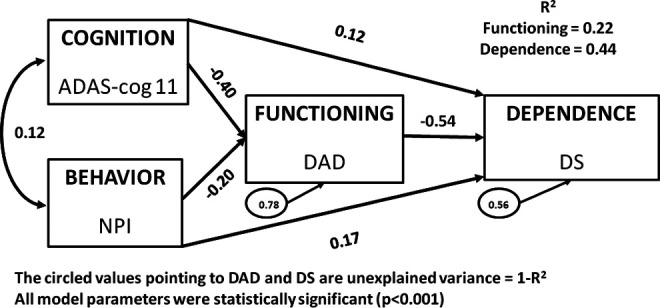

The hypothesized model in Figure 1 was tested in the 3 data sets at baseline and again at Week 78. Because the 3 baseline models demonstrated notable consistency, only the pooled data set results are presented in Figure 2. In all 3 models, 22% of the variation in functioning as measured by the DAD was explained by cognition and behavior as measured by the ADAS-cog and the NPI, respectively. Similarly, 43% to 44% of the variation in the DS was explained by the DAD, ADAS-cog, and NPI in all 3 baseline models; that is, 56% to 57% of the variation in the DS is not accounted for by these related yet distinct AD trial measures. The standardized β coefficients across all estimated paths were also similar; for example, the path from the DAD to the DS ranged from −.56 to −.52 for each model, with all parameter estimates statistically significant in all 3 models (P < .001).

Figure 2.

Theoretical model of Cognition, Behavior, Functioning, and Dependence: Pooled 301 and 302, baseline (N = 2334).

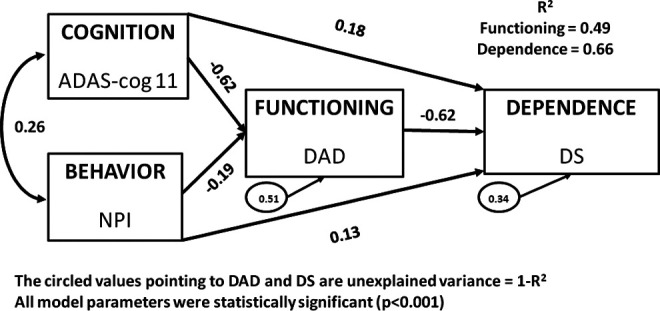

In the same manner as the baseline models, the 3 Week 78 models also demonstrated notable consistency but with some stronger relationships than those seen at baseline (see Figure 3 for the pooled data results). In all 3 models, 49% of the variation in functioning as measured by the DAD was explained by cognition and behavior as measured by the ADAS-cog and the NPI, respectively. Similarly, 66% of the variation in the DS was explained by the DAD, ADAS-cog, and NPI in all 3 baseline models, demonstrating that at least a third of the variation in the DS is not accounted for by other components in this fully saturated model. Like the baseline models, these Week 78 models demonstrate that not all of the variation in the DS is explained by these other key construct measures of AD and provide support of the DS as a distinct measure from the DAD, ADAS-cog, and NPI. The standardized β coefficients across all estimated paths were also similar across the 3 week 78 models, and all were statistically significant with P < .001.

Figure 3.

Theoretical model of Cognition, Behavior, Functioning, and Dependence: Pooled 301 and 302, Week 78 (N = 1807).

Interpretation of Scores: Responder Definition

Using the 3 data sets, mean change scores from baseline to Week 78 for DS were calculated and presented by baseline to Week 78 EIC residential change status (Table 5). It is important to note that due to very few patients (≤7 in each study) entering the study with a baseline EIC status of health-related facility, small sample sizes prohibited the analysis of change over time by EIC status in these patients.

Table 5.

Mean Change in the DS From Baseline to 78 weeks by Change in the Equivalent Institutional Care.

| EIC Change Status | Study 301 (N = 949) | Study 302 (N = 846) | Pooled Study 301 and Study 302 (N = 1795) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea | N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea | N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea | |

| Limited home care (stable) | 551 | 0.9 (2.1) | – | 472 | 0.8 (2.0) | – | 1023 | 0.8 (2.1) | – |

| Limited home care to adult home/assisted living care | 231 | 2.3 (2.5) | <.0001 | 216 | 2.1 (2.1) | <.0001 | 447 | 2.2 (2.3) | <.0001 |

| Limited home care to health-related facility | 23 | 5.4 (2.3) | <.0001 | 23 | 5.0 (1.7) | <.0001 | 46 | 5.2 (2.0) | <.0001 |

| Adult home/assisted living care (stable) | 84 | 1.5 (2.1) | – | 79 | 1.8 (2.3) | – | 163 | 1.7 (2.2) | – |

| Adult home/assisted living care to health-related facility | 15 | 3.3 (2.0) | .0017 | 18 | 3.1 (2.8) | .0413 | 33 | 3.2 (2.5) | .0003 |

| Adult home/assisted living care to limited home care | 45 | 0.2 (1.8) | .0004 | 38 | 0.4 (2.1) | .0026 | 83 | 0.3 (1.9) | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: DS, Dependence Scale; EIC, Equivalent Institutional Care; SD, standard deviation.

a P value for comparison to respective stable care (bolded value) using Dunnett’s test.

The patients of Study 301 and Study 302 in a limited home care setting who remained stable in that setting over 18 months had change scores that were, on average, approximately 1 point (Table 5). Those who worsened over time had statistically significant mean change scores (2.3-5.4 points) compared to the stable patients (P < .0001). The stable study participants who entered either Study 301 or 302 with an assisted living care assessment demonstrated a slightly higher average change score closer to 2 points than 1 point (range: 1.5-1.8 points) while those who worsened to a health-related facility placement had a mean change of 3.1 to 3.3 points. Finally, those who improved in their assessed care over the 78-week study had a smaller mean change score of approximately 0.3 points as shown in the last row of Table 5.

Subgroup analyses

In addition to the proposed primary analysis mentioned earlier to confirm the a priori responder definition, additional confirmatory analysis was conducted in separate subgroups of patients with mild (MMSE ≥ 21) and moderate (MMSE ≤ 20) AD using baseline MMSE scores to examine the appropriateness of the responder definition in each of these 2 severity subgroups in each of the 3 data sets (Table 6). In the patients with mild AD, patients whose residential status remained stable changed approximately 1 point (0.5-1.1) in the DS mean score; however, those experiencing a decline in their EIC allocation had category mean change scores of approximately 2 points (1.9-5.2). In the moderate patients, higher mean change scores were observed; the stable patients changed approximately 2 points (1.3-2.2) while those experiencing a decline in their EIC allocation had larger category mean change scores (2.3-5.7). This suggests that a responder threshold of 2 points may be more appropriate to define stability in patients with moderate AD over 18 months (Table 6).

Table 6.

Confirming the Responder Definition in the Mild AD Population (MMSE ≥21) and Moderate AD Population (MMSE ≤20): Mean Change in the DS from Baseline to 78 weeks by Change in the Equivalent Institutional Care.

| Mild AD Population (MMSE ≥21) EIC Change Status | Study 301 (N = 577) | Study 302 (N = 451) | Pooled Study 301 and Study 302 (N = 1028) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea | N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea | N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea | |

| Limited home care (stable) | 402 | 0.6 (2.0) | – | 301 | 0.5 (2.0) | – | 703 | 0.5 (2.0) | – |

| Limited home care to adult home/assisted living care | 117 | 2.0 (2.3) | <.0001 | 90 | 1.9 (2.2) | <.0001 | 207 | 2.0 (2.2) | <.0001 |

| Limited home care to health-related facility | 6 | 4.7 (1.6) | <.0001 | 10 | 5.2 (1.6) | <.0001 | 16 | 5.0 (1.6) | <.0001 |

| Adult home/assisted living care (stable) | 31 | 1.1 (2.4) | – | 29 | 1.2 (2.4) | – | 60 | 1.1 (2.4) | – |

| Adult home/assisted living care to health-related facility | 2 | 5.0 (2.8) | .018 | 3 | 2.0 (2.0) | .3853 | 5 | 3.2 (2.6) | .0405 |

| Adult home/assisted living care to limited home care | 19 | 0.2 (1.6) | .1334 | 18 | 0.2 (1.7) | .1139 | 37 | 0.2 (1.6) | .0325 |

| Moderate AD Population (MMSE ≤20) | Study 301 (N = 372) | Study 302 (N = 395) | Pooled Study 301 and Study 302 (N = 767) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIC Change Status | N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea | N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea | N | Mean (SD) | P Valuea |

| Limited home care (stable) | 149 | 1.7 (2.2) | – | 171 | 1.3 (2.0) | – | 320 | 1.5 (2.1) | – |

| Limited home care to adult home/assisted living care | 114 | 2.5 (2.6) | .0105 | 126 | 2.3 (2.1) | .0001 | 240 | 2.4 (2.4) | <.0001 |

| Limited home care to health-related facility | 17 | 5.7 (2.5) | <.0001 | 13 | 4.9 (1.8) | <.0001 | 30 | 5.4 (2.2) | <.0001 |

| Adult home/assisted living care (stable) | 53 | 1.7 (1.8) | – | 50 | 2.2 (2.2) | – | 103 | 2.0 (2.0) | – |

| Adult home/assisted living care to health-related facility | 13 | 3.0 (1.8) | .0283 | 15 | 3.3 (3.0) | .1199 | 28 | 3.1 (2.5) | .0091 |

| Adult home/assisted living care to limited home care | 26 | 0.2 (1.9) | .0007 | 20 | 0.7 (2.4) | .0155 | 46 | 0.4 (2.1) | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; DS, Dependence Scale; EIC, Equivalent Institutional Care; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SD, standard deviation.

a P value for comparison to respective stable care (bolded value) using Dunnett’s test.

Receiver–operating characteristic analyses

The ROC analysis in the pooled data set for all patients with a stable EIC classification of limited home care between baseline and Week 78 compared to those who were at this status at baseline but declined in EIC status at Week 78 confirmed a ≤1-point change as the optimal threshold, with an AUC of 0.69 that approached acceptable discrimination. 25 This same cut point was also confirmed in the mild (AUC = 0.71) and moderate (AUC = 0.64) subgroup analyses. However, the ROC analyses examining patients with a stable EIC classification of adult home/assisted living versus those with this status at baseline who declined to health-related facility at Week 78 was optimized at a cut point of a point ≤2-point change for the overall pooled data set (AUC = 0.75) and in the ROC subgroup analysis among patients with moderate AD at screening (AUC = 0.72). The mild AD subgroup had too few (n = 5) patients in the adult home/assisted living status at baseline with a decline at Week 78 to conduct the ROC analysis.

Discussion

Since the development of the DS as an AD measurement tool to capture the need for assistance from others, 1 the instrument has been incorporated into numerous contemporary studies, including a phase 2a clinical trial 26 and economic studies modeling the cost of AD care. 27 –30 Most notably, the DS has been a key element in AD observational outcomes studies that: examined the relationship between patients with AD dependence and caregiver burden 13,31 ; investigated the relationship between dependence on others and AD resource use 32 ; explored economic evaluations of dementia interventions 15 as well as clinical end points 16 ; investigated the association between dependence and social care costs, patient- and proxy-assessed health-related quality of life (HRQL), caregiver burden and key clinical measures 14,33,34 ; and predicted changes in HRQL 28 and need for home health aide services. 35

The psychometric analyses of the DS in this analysis using the data from 2 large RCTs provided evidence of adequate internal consistency reliability, robust known-groups validity, strong construct validity, and the ability to detect change over time. Moreover, path models using these data (1) empirically corroborated the hypothesized relationship of the DS with ADAS-cog, the NPI, and the DAD; (2) reinforced the meaningfulness of including these 4 end points in AD clinical trials; and (3) further supported dependence as a “distinct, measurable component of dementing disease, which ought to be an important outcome in studies of AD.” 1

The a priori responder definition, where EIC stability over 18 months is signified by a change of 1 point or less on the DS, was supported by the mean change scores and ROC analyses of all patients when their baseline EIC status was limited home care. However, for patients who entered these clinical trials with an EIC status of adult home/assisted living, mean change scores suggested and ROC analyses confirmed that patient change scores of 2 points or less best describe EIC stability. These interpretation thresholds, anchored by EIC status, will greatly assist the interpretation of treatment-associated changes in the DS and aid in communicating results at the individual level; however, other anchors capturing important dependence-related changes over time should be considered in future trials to bolster understanding of change scores elicited from this important AD measure of need for assistance from others.

These results support the DS as a valid end point in clinical trials of patients with mild to moderate AD. It is increasingly important to demonstrate the relevance of other AD measures in the progression of this disease beyond cognition and known AD biomarkers; the DS is an addition to the current AD outcome measures toolkit that provides valuable insight into the patient’s need for assistance as the illness progresses. Although this investigation provides a strong understanding of the DS in patients with mild and moderate AD, additional research is needed to understand the psychometric properties of this measure of dependence at the early stages of AD (prodromal) and in patients with severe AD.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Wen-Hung Chen, PhD, for statistical support on the Rasch analyses and Ren Yu, MA, for statistical support on the analyses of reliability and validity.

Footnotes

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Kathleen Wyrwich and Priscilla Auguste were full-time employees of United BioSource Corporation, which was the paid consulting organization to Pfizer Inc and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC in connection with the development of this manuscript. Christopher Leibman, Loretto Lacey, and Robert Brashear were full-time employees of Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC and Katja Rudell and Tara Symonds were full-time employees of Pfizer Ltd when the project was conducted. Jacqui Buchanan was a paid contractor to Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC, in the development of this manuscript.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The work described here (post hoc analyses of clinical trial data) was sponsored by Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC, and Pfizer Inc.

References

- 1. Stern Y, Albert SM, Sano M, et al. Assessing patient dependence in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49(5):M216–M222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lenderking W, Wyrwich KW, Stolar M, et al. Reliability, validity, and interpretation of the dependence scale in mild to moderately severe Alzheimer’s Disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(8):738–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wyrwich KW, Frank F, Leibman C, Mucha L, McLaughlin T. Psychometric properties and clinical significance of the dependence scale as an outcome in Alzheimer’s disease. Paper presented at : 2nd Annual Conference of Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease; October 29-30, 2009; Las Vegas, NV. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frank L, Howard K, Jones R, et al. A qualitative assessment of the concept of dependence in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(3):239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scheltens P, Sperling R, Salloway S, Fox N. Bapineuzumab IV phase 3 results. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(9):795–872.23131822 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261(5123):921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mohs RC, Knopman D, Petersen RC, et al. Development of cognitive instruments for use in clinical trials of antidementia drugs: additions to the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale that broaden its scope. The Alzheimer’s disease cooperative study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(suppl 2):S13–S21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gelinas I, Gauthier L, McIntyre M, Gauthier S. Development of a functional measure for persons with Alzheimer’s disease: the disability assessment for dementia. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53(5):471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wimo A, Winblad B. Resource Utilization in Dementia: “RUD Lite”. Brain Aging. 2003;3(1):48–59. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gallagher D, Ni Mhaolain A, Crosby L, et al. Dependence and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26(2):110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones RW, Lacey LA, Knapp M, et al. Relationship between patient dependence on others and clinical measures of cognitive impairment, functional disability and behavioural problems in Alzheimer’s disease (AD): results from the Dependence in AD in England (DADE) study. Paper presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC); July 17, 2012; Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 15. McLaughlin T, Buxton M, Mittendorf T, et al. Assessment of potential measures in models of progression in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2010;75(14):1256–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu CW, Leibman C, Townsend R, et al. Bridging from clinical endpoints to estimates of treatment value for external decision makers. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(3):256–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hays RD, Revicki DA. Reliability and validity, including responsiveness. In: Fayers PM, Hays RD, eds. Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. Decision analytic models for Alzheimer’s disease: state of the art and future directions. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(3):212–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McLaughlin T, Feldman H, Fillit H, et al. Dependence as a unifying construct in defining Alzheimer’s disease severity. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(6):482–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murman DL, Von Eye A, Sherwood PR, Liang J, Colenda CC. Evaluated need, costs of care, and payer perspective in degenerative dementia patients cared for in the United States. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(1):39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry on patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Fed Regist. 2009;74(235):65132–65133. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dunnett CW. New tables for multiple comparisons with a control. Biometrics. 1964;20(3):482–491. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hanley JA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) methodology: the state of the art. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1989;29(3):307–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vellas B, Black R, Thal LJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients immunized with AN1792: reduced functional decline in antibody responders. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6(2):144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murman DL, Charlton M, High R, Leibman C, McLaughlin T. Predicting costs of care for unique dependence levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(4 suppl):P408. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murman DL, Charlton M, High R, Leibman C, McLaughlin T. Estimating health-related quality of life for unique dependence levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(4 suppl):P236. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhu CW, Leibman C, McLaughlin T, et al. The effects of patient function and dependence on costs of care in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(8):1497–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu CW, Leibman C, McLaughlin T, et al. Patient dependence and longitudinal changes in costs of care in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(5):416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lacey LA, Jones RW, Trigg R, Niecko T, for the DADE investigator group. Caregiver burden as illness progresses in Alzheimer’s disease (AD): association with patient dependence on others and other factors: results from the Dependence in AD in England (DADE) study. Paper presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC); July 16, 2012; Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 32. McLaughlin T, Neumann P, Spackman E, et al. Increasing dependence on others is associated with increased resource use in dementia. Paper presented at: Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease 9th International Conference; March 11-15, 2009; Prague, Czech Republic. [Google Scholar]

- 33. King D, Knapp M, Romeo R, et al. Relationship between healthcare and social care costs and patient dependence on others as illness progresses in Alzheimer’s disease (AD): results from the Dependence in AD in England (DADE) study. Paper presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC); July 16, 2012; Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trigg R, Jones RW, Lacey LA, Niecko T, for the DADE investigator group. Relationship between patient self-assessed and proxy-assessed quality of life (QoL) and patient dependence on others as illness progresses in Alzheimer’s disease (AD): results from the Dependence in AD in England (DADE) study. Paper presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC); July 16, 2012; Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scherer RK, Scarmeas N, Brandt J, Blacker D, Albert MS, Stern Y. The relation of patient dependence to home health aide use in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(9):1005–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]