Abstract

Background:

Accumulating evidence suggests repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) may be beneficial in ameliorating cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods:

AD patients received four high-frequency rTMS sessions over the bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) over two weeks. Structured cognitive assessments were administered at baseline, at 2 weeks after completion of rTMS, and at 4 weeks post treatment. At these same times, tolerant patients underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while performing structured motor and cognitive tasks. We also reviewed literature regarding the effects of rTMS on cognitive function in AD.

Results:

A total of 12 patients were enrolled, eight of whom tolerated the fMRI. Improvement was seen in Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination tests of verbal and non-verbal agility 4 weeks post-treatment. The fMRI analysis showed trends for increased activation during cognitive performance tasks immediately after and at 4 weeks post-treatment. Our literature review revealed several double-blind, sham-controlled studies, all showing sustained improvement in cognition of AD patients with rTMS.

Conclusions:

There was improvement in aspects of language after four rTMS treatments, sustained a month after treatment cessation. Our results are consistent with other studies and standardization of treatment protocols using functional imaging may be of benefit.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, rTMS, fMRI

Introduction

Recent research has found that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is beneficial in ameliorating the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). 1 –7 However, optimal stimulation parameters, including length of treatment, frequency, and specific cortical areas to stimulate have not yet been standardized. In addition, simultaneous functional imaging correlates have not been explored.

Due to its ability to modulate regional cortical excitability, rTMS was first used to explore potential language processing centers in normal individuals. In particular, Cappa et al focused on the involvement of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in language. 8 They found that high-frequency rTMS over the right and left DPLFC in normal individuals was successful in improving language abilities including action naming, sentence comprehension, and idiom comprehension. 8 –10 Improvement in attention and memory, sustained after 1 month, was seen in normal individuals stimulated over the left DLPFC. 11 Functional modulation of the DLPFC seems to have widespread effects on both language and cognition.

If the naming impairment in early AD is indeed caused by inefficient access to semantic knowledge, rather than true loss of semantic representations, then rTMS might help to compensate the functional decline by both activating the original language-related networks and facilitating the recruitment of additional cortical areas. 2,12 Cotelli et al explored both the short-term and the long-term effects of high-frequency rTMS in AD. 3 They found both immediate improvement in naming after a single session of rTMS and sustained improvement in language and cognition 2 months after 2 to 4 weeks of rTMS in patients with AD. 1 –3

Following Cotelli, Ahmed et al found that high-frequency stimulation bilateral rTMS over the DLPFC over 5 days in patients with AD led to sustained cognitive improvement 3 months later. 4 Cognitive training in conjunction with rTMS has also led to improved cognition in a more intense stimulation protocol over Broca and Wernicke areas, bilateral DLPFC, and bilateral parietal somatosensory association cortex over 4.5 months of ongoing treatment in AD. 5,6

The DLPFC area has been implicated in facilitation of language in various studies with a crucial role for action naming and language tasks. 1 –7 An early study found a “causal role of the DLPFC in action naming” among patients with AD as well as shortened naming latency. 1 The rTMS effect was lateralized to the dominant hemisphere in normal controls but bilateral facilitation was observed in patients with AD. 1 The authors speculate that this may be due to compensatory networks being recruited from the nondominant hemisphere to augment failing dominant hemisphere language and memory networks as seen even in normal aging. 1 Such plasticity is seen early in the course of AD. 1 –7

In a small, open-label, exploratory study of rTMS in patients with AD, we evaluated concomitant changes in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and the effect of varying rTMS treatment frequency on language and cognition. We hypothesized that short-term rTMS over the DLPFC would result in improved language-related cognitive abilities with concurrent increased activation in language-related cortical areas on fMRI, with higher frequencies leading to more robust outcomes.

Methods

Patients

Patients meeting the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for possible or probable AD were recruited from a memory disorders practice. Recruited patients had no contraindication for undergoing rTMS and were on approved treatments for AD with objective evidence of aphasia on their diagnostic neurocognitive testing, an extensive, standardized battery. The study was approved in 2008 by the institutional review board and completed in 2012.

Inclusion criterion for the study was objective evidence of aphasia based on cutoff scores on Category fluency (CFL) naming and the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE).

For all patients, assent was obtained from the patient and consent from a legally authorized representative who in all instances happened to be the spouse and caregiver. Exclusion criteria included newly diagnosed AD, pacemaker placement, a history of implanted metal object, seizures or epilepsy, a recent history of migraines, uncontrolled depression, and those on medications lowering the seizure threshold.

Patients were seated and resting before receiving rTMS and this was done “off-line,” that is, not while the patient was being imaged.

Study Flow

Patients underwent 4 sessions of rTMS over 2 weeks with structured, limited, cognitive evaluation, and fMRI imaging at baseline, immediately after the 4 rTMS sessions (post-rTMS) and 4 weeks post-treatment (follow-up).

The Magstim Rapid2 stimulator with a peak magnetic field of 0.5 to 3.5 Tesla at 100% output was used. Patients received 4 sessions of rTMS over 2 weeks and underwent cognitive tasks at baseline, post-rTMS, and 4 weeks later at follow-up. We chose 4 rTMS sessions over 2 weeks as this was a clinically feasible schedule. All patients received stimulation to bilateral DLPFC regions for all 4 treatment sessions, with the left hemisphere stimulated first, then the right. Each rTMS session lasted approximately 30 minutes, 2 consecutive days a week for 2 weeks. The first 6 enrolled patients underwent rTMS at 10 Hz in 20 trains of 5 seconds with 20-second intervals between trains in each hemisphere (1000 total pulses), the second 6 patients at 15 Hz in 20 trains of 5 seconds with 25-second intervals between trains in each hemisphere (1500 total pulses). According to Rossi et al, these parameters are consistent with safety recommendations for rTMS of up to 1500 pulses per day. 13 To minimize discomfort due to noise, patients were offered ear plugs.

We localized the DLPFC in the following manner: patients were stimulated using single pulses of low-frequency rTMS over the motor cortex to determine the scalp point at which the movement of first dorsal interosseus (FDI) of the hand contralateral to the stimulated hemisphere became visually observable. The motor threshold was determined as the stimulus intensity needed to cause contraction of the contralateral FDI muscle 50% of the time over 10 stimuli. For each session, the stimulation intensity was determined as 90% of each patient’s motor threshold. We chose this treatment intensity to minimize patient discomfort from muscle twitches. From this point, in the same sagittal plane, a point 5.5 cm anteriorly was located and marked to designate the DLPFC on both sides of the brain. To stimulate the DLPFC, the junction point of the figure 8 MagStim coil was placed directly over the localized region. For 6 patients, we verified this method of localization using a vitamin E pellet during direct visualization of the brain during fMRI. This localization was done by the chief of neuroradiology of the imaging center (L.H.).

Cognitive Assessment

Patients performed structured cognitive assessment tasks at baseline, immediately after fourth rTMS session (post-rTMS) and 4 weeks posttreatment (follow-up). Selected subtests of the BDAE (nonverbal agility, verbal agility, complex ideational material, naming, responsive naming, and commands), CFL, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) were administered in a standardized manner.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

All patients assented to functional imaging to enroll in the study and those who were able to tolerate it underwent imaging. Tasks performed during fMRI scanning were verbally explained to the patients before each study and repeated immediately before each corresponding scan. The patients used foam earplugs for noise protection and headphones with additional noise protection capability. Before scanning, soft padding was placed around the head and anchored by the head coil caging to limit motion.

Images were acquired on a General Electric 3.0 T scanner (GE, Waukesha, WI) using a 2-dimensional gradient echo-planar sequence with echo time/repetition time = 30/2000 milliseconds, flip angle of sinc-shaped excitation pulse = 70, variable acquisition bandwidth = 250 kHz (with ramp sampling), and 24 cm field of view. Twenty-eight axial slices of 4-mm thickness and a matrix size of 64 × 64 were acquired. Tasks were performed in 3 blocks during 3.7 minutes of scanning time. The block length was 30 seconds “on” and 30 seconds “off,” repeated 3 times after an initial off block of 42 seconds. The first 6 acquisitions were discarded to accomplish equilibrium of the spin dynamics, yielding 105 samples in total (sample 1-15 “off,” 16-30 “on,” 31-45 “off,” 46-60 “on,” 61-75 “off,” 76-90 “on,” 91-105 “off”). Direct feedback of the individuals was not recorded.

The following 4 tasks were run on all individuals in the same order:

MOTOR: bilateral sequential tapping of thumb against all opposing fingers of the same hand. During the “off” phase, the word “Stop” and during the “on” phase the word “Go” was displayed on the screen, on a black background.

WORDS: forming words starting with a given letter. Three letters were presented for 10 seconds each during each of the 3 “on” phases, on a black background. During the “off” phases, a black screen was presented.

LANGUAGE ASSOCIATION: The first four patients were given words to rhyme with. Two words were presented for 15 s each during each of the three “on” phases, on a black background. During the “off” phases a black screen was presented. The second four patients performed another language association task, “Pyramids and palm trees”, as adapted by us to make it applicable to our subject population. 14 Three words were presented in two rows, one on top and two below. The subject had to decide which of the two bottom words had the strongest semantic relation to the top word. For example, top word ‘pillow’, semantic alternatives ‘bed’ (correct association) and ‘chair’. The test stimuli were presented on a white background with the top word in blue and the bottom words in red. Ten stimuli of 3 s duration each were presented during each of the three “on” phases. During the “off” phases a black screen was presented.

ACTION: The first 4 patients were given passive naming stimuli of things and animals, the next 4 were given naming actions performed by people or animals shown as line drawings. In all, 10 stimuli were presented for 3 seconds each during each of the 3 “on” phases. During the “off” phases, a black screen was presented.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic variables as well as outcome variables including CFL scores, MMSE scores, and the naming scores on the BDAE before and after rTMS treatment were evaluated using Student paired t tests in the SPSS statistical package. Nonparametric tests were used to test for differences between sexes. Additionally, a series of univariate, 1-way repeated measures analyses of variances (ANOVAs) were conducted for the various language assessments at baseline, post-rTMS and at week 4 follow-up as the repeated measure. Subsequent to the ANOVA, comparisons of individual means were done through the Newman-Keuls correction procedure.

For fMRI analysis, statistical parametric maps were computed using BrainVoyagerQX version 1.10.4.1250. 15 Volumes of time series were corrected for slice scan-time differences and for motion, spatially filtered with a 3D Gaussian smoothing kernel, corrected for linear trends, and autocorrelation corrected by an AR 1 filter. The time-series volumes were then coregistered to the 3-dimensional anatomical volumes, and these were normalized to Talairach coordinates. For the computation of statistical parametric maps, general linear models were used, 16 taking the 6 motion correction parameter time series into account as nuisance variables that were regressed out. The hemodynamic response function was modeled by γ functions. The results of all single-patient and group analyses were thresholded using the false-discovery rate, which was calculated for P < .05. 17,18 For each patient, a group analysis over the 3 time points was performed to define regions of interest (ROIs) for an analysis of changes over time by searching for the strongest activation (by means of P values) in the brain, separately for each hemisphere (all paradigms) and near the midline of the brain (only paradigms 2, 3, and 4).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and cognitive outcome variables were evaluated using Student paired t tests (SPSS). Nonparametric tests evaluated for differences between sexes. A series of univariate, 1-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used for the cognitive evaluations conducted at baseline, post-rTMS, and at week 4 follow-up as a repeated measure. Individual means were compared with the Newman-Keuls correction procedure.

Standard fMRI analysis wasere computed using general linear models (BrainVoyagerQX version 1.10.4.1250). For each patient, a group analysis at baseline, post-rTMS, and at week 4 follow-up was performed to define ROIs for an analysis of changes over time by searching for the strongest activation (by means of P values) in the brain, separately for each hemisphere, and near the midline of the brain.

Results

In all, 12 native-English speaking, Caucasian patients (7 male and 5 female) with an average age of 73.1 (± 7.9) years and with an average education of 18.2 (± 2.7) years were enrolled. There was no demographic difference between high- and low-frequency stimulation groups. All patients tolerated rTMS well and had no adverse side effects.

Cognitive Testing

Directly following rTMS administration, there was an improvement in the BDAE verbal agility (oral expression) compared to baseline (P < .05). This improvement was sustained along with improvement in nonverbal agility (oral expression) at 4 weeks posttreatment follow-up compared to baseline (P < .05). Other tests did not reach statistical difference (Table 1).

Table 1.

Changes in Patient (N = 12) Cognitive Test Scores at Baseline, Post-rTMS, and at 4 Weeks Follow-Up. P Values Reflect Baseline Versus 4 Week Change in Score.

| Test/Total Score | Baseline | Post-rTMS | 4 Week Follow-Up | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE/30 | 25.1 ± 5.8 | 25.3 ± 6.2 | 24.6 ± 7.2 | NS |

| COWAT (CFL) | 53.4 ± 24.8 | 56.6 ± 23.4 | 57.2 ± 29.8 | NS |

| BDAE naming/15 | 12.8 ± 3.8 | 13.1 ± 3.7 | 12.4 ± 4.3 | NS |

| BDAE responsive naming/ 20 | 18.8 ± 4.0 | 18.8 ± 4.0 | 18.8 ± 4.0 | NS |

| BDAE commands/15 | 14.3 ± 2.3 | 14.0 ± 3.5 | 14.0 ± 3.5 | NS |

| BDAE complex ideation/8 | 6.4 ± 2.5 | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 6.4 ± 2.5 | NS |

| BDAE nonverbal agility/12 | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 9.5 ± 1.7 | 10.2 ± 2.3 | <.03 |

| BDAE verbal agility/14 | 11.6 ± 3.2 | 12.4 ± 2.9 | 12.6 ± 2.8 | <.02 |

Abbreviations: MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; CFL, Category fluency; BDAE, Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination; NS, not significant.

a P values reflect baseline versus 4 week follow-up change in score.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analysis

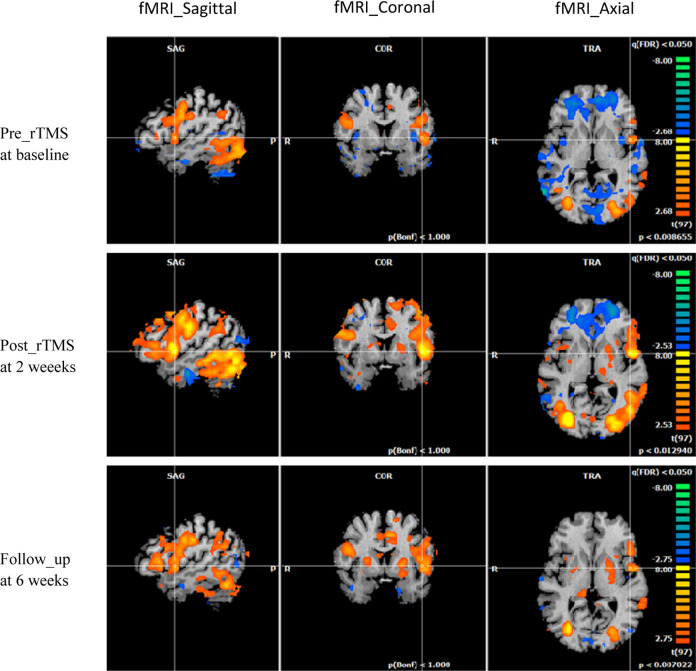

A total of 8 of 12 patients completed the fMRI imaging while completing language tasks. On fMRI analysis, there was increased activation of Broca’s area during cognitive tasks in some patients’ post-rTMS and at follow-up (Figure 1) in the point of interest areas, but no statistically significant change was observed overall. Additionally, stratifying by intensity of stimulation failed to yield observable differences, confounded by the low numbers in each group.

Figure 1.

Left sagittal, coronal, and axial fMRI scans of a single study patient at baseline, post-rTMS, and 4 weeks follow-up while performing action word generation tasks showing increased activation over Broca’s area. Peak t value at (A) 5.7, (B) 11.7, (C) 10.3. fMRI indicates functional magnetic resonance imaging; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Varying Levels of Frequency

There was no observable difference in cognitive outcomes or activation patterns between 10 Hz and 15 Hz stimulation parameters.

Discussion

Our small open-label study demonstrates immediate and sustained improvement of selected cognitive parameters in patients with AD, primarily verbal and nonverbal agility. This is suggestive of improvement in communication-related deficiencies, such as those seen in ideomotor apraxia. There was a trend for concomitant increased activation among some patients of Broca’s area post-rTMS, but this did not approach statistical significance, given the small numbers of patients. We did not find the improvement in naming noted in other studies, possibly because we used the 15-item naming subtest from the BDAE, which did not allow for much variance.

Our results are in keeping with other recent, controlled trials of rTMS in patients with AD, with protocols vastly varying in intensity (Table 2). Cotelli et al pioneered this approach, evaluating a group of patients with AD receiving 4 continuous weeks of rTMS stimulation and a second group receiving 2 initial weeks of sham stimulation, followed by 2 weeks of rTMS stimulation. 3 Both groups received high-frequency rTMS over the left DLPFC for 25 minutes, 5 days per week, with cognitive assessments at 2, 4, and 8 weeks posttreatment. They found a sustained improvement in auditory sentence comprehension. 3 Interestingly, they did not find any added benefit following a 2-week versus 4-week schedule of stimulation, supporting our finding that limited rTMS is sufficient to induce sustained, positive changes in the cognition of patients with AD.

Table 2.

Summary of Experimental Parameters and Cognitive Results of Studies of rTMS in Patients With AD.

| Article | n | Mean Age, Years | Hz | Sham | Stimulation Site | Number of Sessions (Total) | Other Variables | rTMS Patient Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotelli et al 1 | 15 | 76.6 | 20 | Y | R/L-DLPFC | (1) | Stimulation during object and action naming task | Improves action naming performance in patients with AD |

| Cotelli et al 2 | 24 | Moderate-severe AD: 77.6; mild AD: 75 | 20 | Y | R/L-DLPFC | (1) | Stimulation during object and action naming task | Improves action naming performance in early and advanced AD |

| Cotelli et al 3 | 10 | 71.2 | 20 | Y | L-DLPFC | 5 days/week for 2 weeks real or placebo, then 2 weeks all real (20) | N/A | Improvement in auditory sentence comprehension (SC-BADA) |

| Ahmed et al 4 | 45 | 68.4 | 1 vs 20 | Y | R/L-DLPFC | 5 days for 1 week (5) | N/A | Improvement in the high-frequency group at all times after treatment (MMSE, IADL and GDS) |

| Bentwich et al 5 | 8 | 75.4 | 10 | N | Days 1, 3, and 5: Broca, Wernicke, R-DLPFC; Days 2, 4: L-DLPFC, pSAC (R and L) | 5 days/week, 6 weeks then 2 days/week for 3 months (54) | Simultaneous cognitive rehab | Improvement in ADAS-cog scores at 6 weeks and 4.5 months |

| Rabey et al 6 | 15 | – | 10 | Y | Days 1, 3, and 5: Broca, Wernicke, R-DLPFC; Days 2, 4: L-DLPFC, pSAC (R and L) | 5 days/week, 6 weeks then 2 days/week for 3 months (54) | Simultaneous cognitive rehab | Improvement in ADAS-cog and CGIC scores |

| Schillberg et al 7 ,a | – | – | 10 | Y | R/L-DLPFC, R/L-parietal cortex, L-superior temporal gyrus, L-inferior frontal gyrus (3 areas/session) | (30) | Simultaneous cognitive rehab | Improvement in ADAS-cog scores and brain plasticity |

| Haffen et al 19 | 1 | 75 | 10 | N | L-DLPFC | 5 days/week for 2 weeks (10) | N/A | Improvements in episodic memory and speed processing 1 month post-rTMS. Improvements lost after 5 months |

Abbreviations: SC-BADA, Sentence Comprehension subtest for Battery for Analysis of Aphasiac Deficits; IADL, Instrumental daily living activity; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale; CGIC, Clinical Global Impression of Change; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; R, right; L, left; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; N/A, not applicable; N, no; Y, yes; pSAC, parietal somatosensory association cortex.

a Abstract only available.

Ahmed et al sought to compare the efficacy of low-frequency inhibition with high-frequency stimulation bilateral rTMS over the DLPFC. In all, 45 patients were randomly assigned to a high-frequency, low-frequency, or sham stimulation group over 5 days. General cognitive performance was assessed at baseline, directly after the last session and at 1 and 3 months post-treatment. Improvement was noted only in the high-frequency rTMS group and sustained 3 months posttreatment. 4

Bentwich et al used both rTMS and cognitive remediation in treating patients with AD, 5 times weekly for the initial 6 weeks, followed by twice weekly treatments for 12 more weeks. Areas stimulated included Broca’s area, Wernicke’s area, bilateral DLPFC, and bilateral parietal somatosensory association cortices. Cognitive abilities were assessed at 6 weeks and 18 weeks of treatment, demonstrating improvement in general cognitive abilities. 5,6

Our literature review found that the number of sessions used varied from a minimum of 5 sessions over 1 week to 54 sessions over 18 weeks (Table 2) with varying numbers of patients. 1 –7,19 We limited our review to studies that focused on patients with AD and did not compare studies of patients with memory complaints, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and dementia due to other causes. Our study used 4 sessions spread over 2 weeks. Most studies applied 20 Hz as the stimulating frequency, while 1 study applied 10 Hz. We used 10 and 15 Hz stimulating frequencies and found no difference between these in efficacy. Additionally, areas stimulated were restricted to DLPFC in some studies, including ours, or wide ranging, involving multiple brain regions. Stimulation parameters, including length of treatment, cortical regions to be stimulated, and frequency of stimulation are still being refined to optimize patient treatment regimes. Functional mapping correlates may also be beneficial in refining the stimulation parameters. Although our study is a clinical snapshot, it is the first to attempt correlations between functional mapping and long-term cognitive changes in patients with AD receiving rTMS. One other study evaluated immediate changes in functional imaging in patients with AD. Sole-Padulles et al evaluated 39 patients with a year of memory complaints without dementia with an average MMSE score of 26 and applied a single course of high frequency stimulation to the left DLPFC with fMRI before and after this single treatment. 20 There was increased recruitment of associated cortical areas in the active treatment arm on fMRI associated with improvement on cognitive testing. Patients’ response to treatment over the long term was not available.

When assessing improvement due to rTMS in AD, it is important to acknowledge the comorbidity of AD and depression and the possibility that the observed cognitive improvement may be due to improvement in depression, as similar areas are targeted in both conditions. 21 In 1 study, for example, 6 of 8 patients had a history of depression. 5 In our study, only patients whose depression was controlled and stable were included.

Of note is that our patients on average had a higher MMSE at baseline of 25, when compared to lower baseline MMSEs in Cotelli et al’s (19.7), Ahmed et al’s (18.4) and Bentwich et al’s (22.9) studies. 3 –6 Although all of our patients underwent standardized neurocognitive evaluations at baseline, which were consistent with a diagnosis of probable or possible AD, our patients were less impaired and this may have contributed to the less robust results when compared with these other studies.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not observe a statistically significant increase in Broca area with fMRI analysis following rTMS treatment. In a few patients, we observed increased activation of Broca’s area during fMRI cognitive naming tasks, and these patients showed improvement on the standardized neurocognitive evaluation. However, the interpretation of these trends was limited by small sample size due to several patients’ inability to tolerate the fMRI procedure, a unique limitation of our study as we chose patients with documented aphasia, which brings additional cognitive limitations to following directions for functional imaging. Recent attempts to combine rTMS and fMRI have found that TMS stimulation can affect both the chosen site and more remote interconnected parts of the brain. 22 Given that our study only measured BOLD measurements within the DPLFC, it is plausible that signals from DPLFC-interconnected sites may correlate more directly with the observed increase in verbal and nonverbal agility. Similarly, peripheral site stimulation may account for our observed improvement in communication-related tasks rather than direct aphasia-related language changes. The use of fMRI in rTMS treatment allows for studying neural plasticity and response to treatment. 23 Fine-tuning stimulation localization methods using fMRI may yield more direct language improvements and fMRI measurements of more discerning insight.

Our study was limited by the lack of a control group, the small number of enrolled patients, and the smaller number of patients who tolerated functional imaging. Furthermore, 3 blocks of image acquisition in 3 minutes of fMRI might be insufficient in detecting task-derived signal change in patients with AD. Even so, our results validate the growing body of research supporting a role for limited rTMS in improving cognitive function in patients with AD. In addition, a role for functional imaging in elucidating the underlying mechanisms is an area that merits further exploration.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The poster presentations of this article was presented at The American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, New Orleans, Louisiana, April 2012; The American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, Montreal, Canada, April 2010; and The European Federation of Neurological Sciences Congress, Milan Italy, March 2009.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Cotelli M, Manenti R, Cappa S, et al. Effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation on action naming in patients with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(11):1602–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cotelli M, Manenti R, Cappa SF, Zanetti O, Miniussi C. Transcranial magnetic stimulation improves naming in Alzheimer’s disease patients at different stages of cognitive decline. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(12):1286–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cotelli M, Calabria M, Manenti R, et al. Improved language performance in Alzheimer disease following brain stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(7):794–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahmed MA, Darwish ES, Khedr EM, El Serogy YM, Ali AM. Effects of low versus high frequencies of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cognitive function and cortical excitability in Alzheimer’s demential. J Neurol. 2011;259(1):83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bentwich J, Dobronevsky E, Aichenbaum S, et al. Beneficial effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a proof of concept study. J Neural Transm. 2011;118(3):463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rabey J, Dobronevsky E, Aichenbaum S, Gonen O, Marton RG, Khaigrekht M. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training is a safe and effective modality for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized double-blind study. J Neural Transm. 2013;120(5):813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schillberg L, Brem A, Freitas C, et al. Effects of cognitive training combined with transcranial magnetic stimulation on cognitive functions and brain plasticity in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(4):709. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cappa SF, Sandrini M, Rossini PM, Sosta K, Miniussi C. The role of the left frontal lobe in action naming: rTMS evidence. Neurology. 2002;59(5):720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manenti R, Cappa S, Rossini P, Miniussi C. The role of the prefrontal cortex in sentence comprehension: an rTMS study. Cortex. 2008;44(3):337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rizzo S, Sandrini M, Papagno C. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in idiom interpretation: an rTMS study. Brain Res Bull. 2007;71(5):523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marra H, Marcolin M, Forlenza O, et al. Preliminary results: transcranial magnetic stimulation improves memory and attention in elderly with cognitive impairment no-dementia (CIND)–A controlled study. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(4):P389–P392. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pennisi G, Ferri R, Lanza G, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease: a neurophysiological marker of cortical hyperexcitability. J Neural Transm. 2011;118(4):587–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual-Leone A. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120(12):2008–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McGeown WJ, Shanks MF, Forbes-McKay KE, Venneri A. Patterns of brain activity during a semantic task differentiate normal aging from early Alzheimer's disease. Psychiatry Res. 2009;173(3):218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goebel R, Esposito F, Formisano E. Analysis of functional image analysis contest (FIAC) data with brainvoyager QX: from single-patient to cortically aligned group general linear model analysis and self-organizing group independent component analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27(5):392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Worsley KJ, Poline JP, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: A general linear approach. Hum Brain Mapp. 1995;2(4):189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Statist Soc Ser B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15(4):870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haffen E, Chopard G, Pretalli JB, et al. A case report of daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) as an adjunctive treatment for Alzheimer disease. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(3):264–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sole-Padulles C, Bartes-Faz D, Junque C, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation effects on brain function and cognition among elders with memory dysfunction. A randomized sham-controlled study. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16(10):1487–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rutherford G, Gole R, Moussavi Z. rTMS as a treatment of Alzheimer’s disease with and without comorbidity of depression: a review. Neuroscience J. 2013;(2013):679389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruff C, Driver J, Bestmann S. Combining TMS and fMRI: From ‘virtual lesions’ to functional-network accounts of cognition. Cortex. 2009;45(9):1043–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pascual-Leone A, Freitas C, Oberman L, et al. Characterizing brain cortical plasticity and network dynamics across the age span in health and disease with TMS-EEG and TMS-fMRI. Brain Topogr. 2011;24(3-4):302–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]