Abstract

This study investigates the feasibility of a Latin dance program in older Latinos with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) via a feasibility mixed methods randomized controlled design. Spanish-speaking older Latinos (N = 21, 75.4 [6.3] years old, 16 females/5 males, 22.4 [2.8] Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score) were randomized into a 16-week dance intervention (BAILAMOS) or wait-list control; the control group crossed over at week 17 and received the dance intervention. Feasibility was determined by assessing reach, retention, attendance, dance logs, and postintervention focus groups. Reach was 91.3% of people who were screened and eligible. Program retention was 95.2%. The dropout rate was 42.8% (n = 9), and attendance for all participants was 55.76%. The focus group data revealed 4 themes: enthusiasm for dance, positive aspects of BAILAMOS, unfavorable aspects of BAILAMOS, and physical well-being after BAILAMOS. In conclusion, older Latinos with MCI find Latin dance as an enjoyable and safe mode of physical activity.

Keywords: mild cognitive impairment, physical activity interventions, dance interventions, minorities, day care centers

Introduction

Older Latinos account for 3.6% of the older adult population in the United States and are projected to account for 21.5% of the older adult population by 2060. 1 Older Latinos are disproportionately affected by chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity compared to non-Latino whites. 2 Presence of these chronic diseases, compounded with poverty and low education levels, increases the risk of cognitive decline and risk of dementia in this population. 2 Older Latinos experience Alzheimer’s disease (AD) symptoms 6.8 years earlier 3 and are 1.5 times more likely to have AD than non-Latino whites. 4 Alzheimer’s disease is often diagnosed after mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a term used to describe a state in which a person has cognitive decline, but it is not severe enough to meet the diagnostic criteria for dementia nor does it impact everyday activities. 5 A study involving a large population-based cohort of ethnically, linguistically, and educationally diverse older adults found that those who self-identified as Latino, had low education levels, and had a history of diabetes were at higher risk of developing MCI compared to non-Latino whites. 6 Interventions that slow cognitive decline among persons with MCI are critical in order to prevent or delay conversion to AD. 6 Evidence indicates that pharmacological interventions in individuals with MCI have had little/no significant benefit in delaying the progression to AD 7 ; however, participation in physical activity (PA) has been shown to improve cognitive function in older adults with MCI. 8

Numerous studies have found that PA can improve chronic diseases and cognition. 9,10 Unfortunately, Latinos aged 65 to 74 are 46% less likely to engage in leisure-time PA than older non-Latino whites. 11 Older Latinos participate in an average of 11 minutes of leisure-time PA per day, 12 while the recommendation is 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity at least 5 days per week to obtain health benefits. Older Latinos understand the physical and psychological benefits of exercise. 13 However, this understanding has not led to the adoption and maintenance of PA.

Interventions that target older Latinos with MCI should use culturally appropriate forms of PA. 14 Older Latinos are known to prefer music, singing, and dance as ways to remain physically active. 15 Dance has been an important form of socialization, entertainment, and leisure in Latin American cultures. 16,17 The few studies that have examined the effects of dance on the health of older adults indicate that older adults who dance on a regular basis have greater flexibility, postural stability, balance, physical reaction time, and cognitive performance than older adults who do not dance. 18 A recent systematic review of dancing in care homes found improvements in decreasing problematic behaviors, enhancing mood, communication, and socialization after dancing. 19 Dance also requires individuals to observe, plan, monitor, and execute dance sequences and turns, which may increase the activity of the premotor cortex and impact brain plasticity, 20 thus making it a top option for preventing cognitive decline. Moreover, studies show that dance interventions may address older adults’ barriers to being physically active such as cultural preferences, preexisting medical conditions, and physical limitations. 21 Older Latinos also find dancing enjoyable, 22,23 which might lead to increased PA maintenance. 24

To date, most PA interventions targeting older adults have excluded individuals with MCI either through explicit criteria or because such individuals are thought to have poor memory or are unable to complete the programs or assessments. 25 Furthermore, older, underserved populations with MCI are even more grossly underrepresented in the literature, despite the growing literature providing evidence that these populations have the greatest need for interventions. Given these considerations, the aim of this feasibility mixed methods randomized controlled study was to investigate the feasibility and safety of a Latin dance program in community-dwelling older Latinos with MCI attending an adult day service center.

Methods

Sample

Older Latinos were recruited in March to May 2015 via study flyers and announcements at an adult wellness center (AWC) in Chicago to participate in a 16-week Latin dance program. The AWC is an adult day service center that offers bilingual and bicultural services to the Spanish-speaking older adult population of Chicago and provides many supervised, structured activities that maintain, improve, and restore participants’ abilities. In order to attend the AWC, individuals must meet certain eligibility criteria, including >60 years old, US citizen, Illinois resident, physician authorization, and a score of 29 or higher on the Determination of Need Assessment. Inclusion criteria for the study were the following: (1) age ≥60 years old, (2) self-identification as Latino/Hispanic, (3) ability to speak or understand Spanish, (4) MCI with scores of 18 to 26 26,27 as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), 28 and (5) no plans to leave the country for more than 2 consecutive weeks over the next 4 months (study duration). Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) regular use of assistance to walk (eg, cane), (2) stroke at any time, (3) >150 minutes of self-reported exercise defined as structured, planned, and repetitive aerobic activity like walking or swimming over an extended period of time with a specific objective such as increasing fitness, physical performance, or health. 29 Additionally, participants who passed initial screening were asked to get medical clearance in order to participate in the research. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of Illinois at Chicago [protocol number: 2014-1067].

Design

The study was a feasibility mixed methods randomized controlled study, with a wait-list control and crossover at 17 weeks. Participants who met the inclusion criteria and completed the baseline testing were randomized to either the dance program or the wait-list condition in June 2015. Randomization was done by computer-generated random numbers and was delivered by a research staff member. The wait-list control group was asked to maintain their usual activities during weeks 1 through 16. At week 17 (October 2015), after the postintervention testing, the wait-list group crossed over and received the 16-week dance program, at which time the intervention group continued their usual activities. Both programs were led by the same professional dance instructor and participated in the same dance program.

Testing

All testing took place at the AWC. This was preferred because participants already attended the AWC, and the space necessary for testing was available. During testing, a bilingual research staff member, blinded to study condition, explained the study and read the informed consent to the participant. After participants agreed to participate, they signed the informed consent. Consent of participants on their own was deemed appropriate, since they had MCI, not dementia.

Intervention

BAILAMOS includes a 4-month, twice-weekly program. Each dance session is 1 hour in length (Table 1). Also, monthly discussion sessions that utilized a social cognitive framework 30 and focused on increasing knowledge, outcome expectations, social support, and self-efficacy in order to increase lifestyle PA were held. Readers can see a previous publication for a detailed description of the program. 22 For the current intervention, a research staff member was present at all dance sessions to set up the room and observe the class. Participants wore an orange Velcro bracelet on their right wrist and a green Velcro bracelet on their left wrist in order to help them distinguish between moves to the left and right. We followed the BAILAMOS manual but were cognizant of elements that seemed to confuse the participants. We recorded such challenges and revised the program as needed. For example, if some of the dance turns that are part of BAILAMOS were too confusing, we revised the moves in ways that still challenged the participants physically and cognitively but did not overwhelm them or put their safety at risk. The monthly discussion sessions were also modified from the original versions to include information about sedentary behavior and the benefits of reducing sedentary time and adding sit-to-stand transitions. During the first discussion session, we provided the participants with visual sedentary behavior feedback in which they were shown an output page of their baseline ActivPAL data and asked to reduce their sedentary time throughout the day.

Table 1.

BAILAMOS Dance Program.a

| Wednesday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 1-hour discussion+ 1-hour instruction | 1-hour instruction |

| Week 2 | 1-hour instruction | 1-hour dance party |

| Week 3 | 1-hour instruction | Instruction |

| Week 4 | 1-hour instruction | 1-hour dance party |

aThe 4-week plan above is repeated for each of the 4 styles of dance. The first day of week 1 for each style dance was 2 hours, with the first hour devoted to discussion of strategies to increase lifestyle physical activity (PA), followed by 1 hour of active dance instruction. The second day of weeks 1 and 3 for each dance style, and the first day of weeks 2, 3, and 4 for each dance style, will be 1 hour of dance instruction. The second day of weeks 2 and 4 for each dance style will be “dance parties” in which participants spend time dancing and practicing what they have learned.

Measures

Background measures

Demographic, health history, and acculturation questionnaires 31 were administered at baseline testing by a bilingual research staff member. Height, weight, blood pressure, and waist circumference were also assessed.

Reach

Reach was calculated as: ([participants enrolled/participants screened and eligible] × 100). 32

Retention

Retention was calculated as: ([participants completing posttesting/participants enrolled] × 100). 32

Intervention attendance

Attendance at each session was recorded. Attendance was calculated as: ([number of dance sessions attended/total number of dance sessions] × 100). Dropouts were those participants who stopped coming to the program and did not come back. Attendance was calculated with and without dropouts.

Dance logs

At the end of every dance session, participants filled out logs with 5 questions. Participants, with assistance from staff if needed, recorded the number of minutes danced that was announced by the instructor and completed the Feeling Scale from −5 (very bad) to +5 (very good) to reflect how they were feeling before, during, and after the class. 33 Participants also recorded ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) using the Borg RPE Scale, a 15-item scale from 6 (no exertion at all) to 20 (maximum exertion). 34 Finally, the participants recorded enjoyment of the dance session on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much).

Dance log completeness

Dance logs were assessed for the rate of completeness. Rate of completeness was calculated as ([log answers completed/log answers possible] × 100).

Dance evaluations

After every dance session, the dance instructor assessed the participants’ energy and focus using a 3-point scale and also assessed participants’ ability to perform the steps using a 3-point scale.

Postprogram focus groups

Focus groups were conducted after each group completed the dance program. All participants were invited to the focus group regardless of attendance rate. The focus groups had a duration of 40 to 60 minutes. A focus group guide was used to examine participants’ perceptions and attitudes of dance 22 and the BAILAMOS dance program. Focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim in Spanish by a bicultural and bilingual research assistant, and translated to English by another bicultural and bilingual research assistant. A directed content analysis 35 was used to identify major themes related to dance and the BAILAMOS program. Directed content analysis is appropriate if prior research about a phenomenon (eg, perceptions of dance among older Latinos with MCI) are incomplete or would benefit from further description. Thus, the content categories of “degree of enthusiasm for dance,” “benefits of dance,” and “BAILAMOS” program were predetermined based on prior research (Table 2). 22 Two researchers coded the data, which involved line-by-line extraction of key phrases from the translated transcripts. As subthemes emerged, the researchers discussed the subthemes among themselves in order to reach consensus over disagreements with coding. Coding agreement between the researchers was reached through one-on-one consultation of the final codes.

Table 2.

Sample Focus Group Questions.

| Content Categories | Questions |

|---|---|

| Degree of enthusiasm for dance |

|

| Benefits of dance |

|

| BAILAMOS program |

|

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS (version 22; IBM Corporation, Chicago, Illinois). Baseline characteristics of the study were analyzed using independent t tests for continuous variables and a χ2 test for categorical variables. Descriptive statistics were conducted for the logs and evaluations. Class-by-class means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated. Because the control group received the dance intervention at week 17, the crossover design allowed us to combine the attendance, logs, and evaluation data for the dance intervention and the wait-list control group, thus the results presented are combined data. Attendance rate was calculated with and without dropouts.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Thirty-three persons expressed interest in the study. Among them, 10 were excluded due to: MMSE <18 (n = 3), MMSE >26 (n = 1), lost interest (n = 2), >150 minutes of exercise (n = 2), died (n = 1), and too cognitively impaired to screen (n = 1). A total of 23 persons were found eligible to participate in the study, but not all enrolled in the study. Reasons for not enrolling were that their physician declined approval (n = 1) and declined to participate (n = 1). Thus, a total of 21 participants enrolled in the study (Figure 1), including a participant of Italian descent, who self-identified as Latina and spoke Spanish due to living over 20 years in Uruguay. Participants’ baseline characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Consort flowchart.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristics | All (n = 21) | Dance (n = 10) | Wait-List Control (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 75.4 (6.3) | 76.0 (6.0) | 74.9 (6.8) |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | 22.4 (2.8) | 21.5 (2.6) | 23.2 (2.8) |

| BMI | 27.7 (4.4) | 26.3 (2.5) | 29.0 (5.5) |

| Waist circumference | 99.1 (9.3) | 95.6 (6.8) | 102 (10.5) |

| Women | 16 (76.2%) | 8 (80.0%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Widow/widower | 8 (38.1%) | 6 (60.0%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Country of birth | |||

| Caribbean | 9 (42.9%) | 5 (41.0%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| South America | 6 (28.5%) | 3 (30.0%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Mexico | 3 (14.3%) | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Central America | 2 (9.6%) | 0 | 2 (18.2%) |

| Italy | 1 (4.8%) | 0 | 1 (9.1%) |

| Years in the United States | 29.5 (20.1) | 31.9 (19.3) | 27 (21.5) |

| Annual income <$10 000 | 11 (52.3%) | 4 (40.0%) | 7 (63.7%) |

| Education | 6.3 (4.3) | 7.2 (5.6) | 5.6 (2.9) |

| Comorbidities | 5.29 (3.48) | 4.30 (2.75) | 6.18 (3.95) |

| Acculturation | |||

| Speak in Spanish only | 14 (66.7%) | 8 (80.0%) | 6 (54.5%) |

| Watch movies and TV and listen to the radio in Spanish only | 13 (61.9%) | 7 (70.0%) | 6 (54.5%) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Reach, Retention, and Attendance

Reach was 91.3% of people who were screened and eligible. Program retention was 95.2%. The dropout rate was 42.8% (n = 9). The most frequent reasons for dropout from the dance program were health-related problems (eg, back and knee pain). The intervention adherence for all participants including dropouts was 55.76%. Not including the dropouts, the intervention adherence was 85%. The average attendance for all participants including dropouts was 17.81 sessions (of 32 total). The average attendance excluding dropouts was 27.17 sessions. Nine participants attended more than 75% of the dance sessions. Three prompt reports were submitted to institutional review board, but none were deemed as adverse. Two participants fell outside of the program and 1 participant fell during the class due to interpersonal coordination but did not suffer any injuries. The AWC had nurses on staff who assessed the participant for any injuries.

Dance Logs

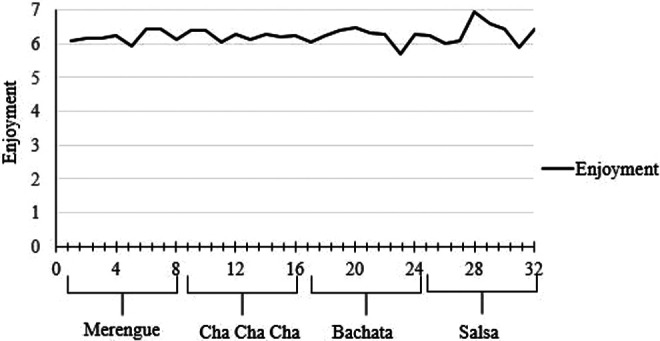

Participants reported feeling “very good” (mean = 3.74, SD = .29) before the dance class started, feeling “very good” (mean = 3.76, SD = .36) during the dance class, and feeling “very good” (mean = 3.76, SD = .32) after the dance class ended. On average, participants’ feelings before, during, and after dance ranged from 2.90 to 4.96 (Figure 2). Participants’ reported a mean RPE of “light” (mean = 10.94, SD = .51, range: 10.08-12.29; Figure 3). This RPE corresponds with light–moderate intensity. 34 Participants’ also reported enjoyment of the dance sessions (mean = 6.25, SD = .23, range: 5.70-6.92; Figure 4). Dance logs had a completion rate of 99%.

Figure 2.

Feelings pre, during, and post dance sessions. The feeling scale ranges from −5 (very bad) to +5 (very good) and was used to reflect how participants were feeling before, during, and after the dance sessions.

Figure 3.

Rating of perceived exertion (RPE) post dance sessions. The Borg RPE Scale includes a 15-item scale from 6 (no exertion at all) to 20 (maximum exertion) and was used to assess how hard participants perceived they were working during the dance sessions.

Figure 4.

Enjoyment of dance sessions. A 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) was used to assess enjoyment of the dance sessions.

Dance Evaluations

On average, the participants’ energy and focus were rated as having “some energy and focus” (mean = 2.55, SD = .20, range: 2.00-2.90). Participants’ dance ability was rated as “somewhat able to do the steps” (mean = 2.42, SD = .29, range: 2.00-2.94; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Dance evaluation by instructor after dance sessions. A 3-point scale was used to assess the participants’ energy and focus (1: Participant is not serious, shows little interest in class; 2: Some energy and focus are shown throughout the class; 3: High, level of energy and focus are shown throughout the class). A 3-point scale was used to assess participants’ ability to perform the steps (1: Did not do the step; 2: Missing some parts of the step; 3: Able to do the step).

Focus Groups

Two focus groups were conducted after completion of the dance program; 7 participants from the dance group (focus group 1) and 6 participants from the control group (focus group 2) participated in the focus groups. A total of 4 themes emerged from the focus groups.

Enthusiasm for dance

Participants talked about their enjoyment of dance. They said it was a great form of exercise because it was a total body exercise (“Because you are exercising your brain, body, arms, legs; your whole body” [translated, Male, 73]). They also mentioned that dancing gave them more energy, without pain and discomfort, and happiness (“And wherever there is dance there is happiness” [translated, Female, 70]); they did not find a need to rest after dancing (“Dancing for exercise doesn’t get you tired for anything” [translated, Male, 73]). Participants also referred to dance as a mindful activity (“It’s good because one has to be mindful of the music, the footing. It puts the hearing and also the physical to use, right. Because you’re doing an exercise. Mentally, physically, one is doing—practicing everything is right. Thus, you put your whole body and mind into the activity. It gets you active and it’s something very positive” [translated, Male, 65]).

Positive aspects of the BAILAMOS program

Participants liked that the program took place after lunch (“One has to do a little exercise so that the food goes and digests. And, thus, the dance has helped us” [translated, Male, 73]) and found the space, amount of participants, and the dance styles in the class appropriate. They thought that the instructor was knowledgeable and provided proper techniques (“And we come to learn…we know how to dance in our own way but to learn, and, well, it’s him that’s teaching the steps and we have to follow him” [translated, Female, 70]). Participants also praised the instructor’s patience (“Ah, beautiful person; very active and that sticks with you; very caring and we liked how he taught us and everything, with a lot of patience” [translated, Male, 75]).

Unfavorable aspects of the BAILAMOS program

Participants did not like that the instructor would turn off the music to show participants the dance moves (“Yes and they take away the music, they take it. And they make us do the exercises without the music; at the very least, I don’t like that” [translated, Female, 80]). Some participants mentioned that they would not do this program again because they prefer freestyle dancing (“And when I dance outside of class, I dance how I want, I have more fun…here I have to be tethered down to the teacher” [translated, Female, 80]). Participants also talked about playing more of a variety of music (“Uhm, notice that the music was good, but, for me, it’d be better that you changed it—to not always put the same CD” [translated, Male, 65]).

Physical well-being after dance sessions

Some participants reported having more energy after the dance sessions took place (“With more energy, one doesn’t finish tired for anything. Dancing for exercise doesn’t get you tired for anything” [translated, Male, 73]). Others reported feeling tired after the class and other attributed their tiredness to aging. Some participants reported feeling tired prior to starting the dance sessions because they had participated in other activities before class started (“It’s that here, a lot of times, the days before the class, they put on music in a classroom or outside and there one dances, dances, and dances. And, later, when you go the class, well, you were already a little tired because you went dancing earlier” [translated, Female, 71]).

Discussion

The goal of this feasibility mixed methods randomized controlled study was to determine the feasibility and safety of a Latin dance program for older Latinos with MCI. Participants (90.6%) in this study reported enjoying the program “very much” and feeling “very good” before, during, and after most dance sessions and deemed the dance styles as a light- to moderate-intensity activity. Furthermore, the focus group data revealed that participants were energized by the dance program, and they enjoyed learning new dance styles and techniques. The participants in the study were also able to fill out logs with a high completion rate. These results suggest the feasibility of implementing a Latin dance program in older Latinos with MCI at the AWC they attended.

Our intervention was shown to have modest attendance (55.76%). Not including the dropouts, the intervention attendance was 85%. Our findings yielded a slightly lower attendance rate in comparison with a 16-week dance intervention for nursing home residents with moderate-to-severe dementia who had a 67% attendance rate. 36 Another study examining the effect of a 12-session psychomotor dance therapy intervention using Danzón Latin ballroom among people with dementia in care homes had a mean attendance of 10.23 (2.048) of 12 sessions. 37 Our dance intervention had 32 sessions and was conducted among older, community-dwelling Latinos with MCI. Other exercise interventions conducted among older adults with MCI have shown varied attendance rates. A year-long walking program among older adults with MCI had a similar attendance (63%) to our intervention, 38 whereas a recent 12-week dumbbell training program had an 86% attendance rate 39 and a 9-week endurance, strength, and balance exercise program had a 90% adherence rate. 25 Differences in attendance may be due to variation in time period of the interventions, community dwelling versus care homes, and differences in cognitive impairment. Individuals who attend adult day service centers such as the AWC are more impaired in which 65% have moderate-to-severe dementia. 40 Participants in this study had a mean MMSE score of 22.4, whereas participants in the other studies had an MMSE score greater than 26. 25,38,39 Although it was a small sample, the participants in this study represent a population at high risk of further cognitive decline. Our participants self-reported multiple comorbidities (mean of 5.3), low income, and low education levels.

The main reasons for dropping out of the program were health-related issues. Participants reported experiencing upper and lower extremity and back pain (n = 5) and one hip fracture (n = 1). The pain experienced by the participants was pain that was already being experienced prior to enrolling into the dance intervention. Some participants mentioned that the dancing ameliorated their pain; however, more thought that it exacerbated their pain. Participants dropped from the program between a range of sessions (3-14). Other reasons why participants dropped from the program were schedule conflicts, 1 participant thought the dance sessions were too difficult, and another participant left the country.

Due to a number of participants dropping from the program due to pain, and given the association between chronic pain and increased risk of falls in older adults, 41 researchers considering working with this population may consider screening people out who experience certain levels of pain or individuals who have had a history of experiencing pain. Also, depending on the source of their pain, certain dance styles may not be appropriate for some participants due to the speed of the music. For example, most participants dropped out during or immediately after the first dance style (merengue). Although merengue is considered the easiest of the 4 dance styles in the BAILAMOS program, it is also the fastest. The movements required to dance merengue are also very repetitive. The fast music along with repetitive movements may have exacerbated participants’ pain, thus causing participants to drop from the program. Future studies may want to assess whether participants can tolerate fast dancing for 1 hour in length. Otherwise, they may consider shortening the time of the classes or removing it for certain populations.

Despite modest attendance, most participants were still willing to complete testing at all testing points; data were available for 94.3% of the participants. We speculate that this was due to the strong rapport we developed with the participants and the AWC staff, and we minimized participant burden by conducting all testing at the AWC. Furthermore, all testing and dance sessions were conducted in Spanish. Pekmezi and colleagues also found that their participants responded favorably when receiving the intervention and information in Spanish. 42

Throughout the dance intervention, we were able to adapt the BAILAMOS manual to make the program safer for participants. For example, the instructor and the principal investigator (DXM) removed the fast turns from all of the dance styles due to the moves involving speedy foot rotations that could increase the risk of falls. Dance moves were simplified and involved more repetition since participants were having a difficult time recalling different moves. The instructor also used an application on his cellular phone to slow down the music. As the dance sessions progressed and participants mastered the steps, the instructor would gradually increase the speed of the music. Also, if participants complained about upper extremity pain, the instructor would modify the movement and ensure that all participants were aware of how to dance with that particular participant who was experiencing pain. Frequent breaks were also taken, and if participants experienced any type of discomfort, the instructor would encourage them to take a seat and join whenever they were ready.

Methodological Challenges

While working with this population, we encountered several challenges that should be considered when designing future PA interventions for persons with MCI. First, the purpose of the research assistant attending all dance sessions was initially to set up the room and observe the sessions. However, many participants needed daily reminders from the research assistant that class was occurring that day; therefore, it was necessary to have a research assistant present at all dance sessions. Also, if the participants were ready to dance but the dance instructor had not yet arrived, the participants would grow impatient, leave the room, and come back once he arrived or not come back at all. Another challenge we experienced was competing activities at the AWC. Other activities such as bingo, dominoes tournaments, AWC parties, and special events frequently competed with participation in the dance intervention. When implementing future interventions with older Latinos with MCI, AWC personnel reminding participants of the importance of attending the exercise program may be needed, and implementing the program during a time where it does not compete with other activities should be considered, if possible.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the focus on older Latinos with MCI, a low MMSE score, persons who speak Spanish, a culturally appropriate PA intervention, and use of mixed methodology to assess feasibility. The limitations of this study were the lack of assessment of pain and falls risk, small sample size, and dropout rate. Future studies may consider fall risk screening, as older adults with cognitive impairment are 5 times more likely to fall than cognitively intact older adults. 43 Also, given the low MMSE score cutoff for inclusion in the study, it cannot be ruled out that participants may have already had dementia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, results from this feasibility study demonstrate that older Latinos with MCI find Latin dance as an appealing, enjoyable, and safe mode of PA. Our results, however, should be interpreted with caution as this study was conducted in a highly controlled environment (AWC) with nurses on staff. Researchers who want to create interventions for community-dwelling older Latinos with MCI who do not have access to resources/services such as the AWC are recommended to conduct another feasibility study that is tailored to meet their needs. If such interventions were to take place in the community, researchers may want to consider the challenges we encountered in our study. Future BAILAMOS interventions should assess recent dance participation, falls, mobility, pain, dementia diagnosis, and medication use. Given the number of participants who experienced pain in this study and its association with increased risk of falls, 41 the next research step for this model may include adapting the program even further by making it chair dance friendly and encouraging mobility-impaired participants to observe the dance session, as studies have shown that there are benefits of dance observation. 44,45 Future PA studies should also involve larger randomized controlled trials and should continue to include ethnic and racial minority populations. By including ethnic and racial minority populations, researchers are targeting one of the goals of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in the United States which is to decrease disparities in AD for populations that are at higher risk of AD. 46 Delaying or reducing the risk of AD and other dementias among older adults should be a priority as improving individuals’ quality of life and maintaining their independence have major positive implications for caregivers, families, and the economy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions and assistance of the Adult Wellness Program at Casa Central, Antonia Laurel, Tatiana Sanjines, study participants, Rebecca Logsdon, Miguel Mendez, Edward Wang, Melissa Lamar, Susan Hughes, Angela Odoms-Young, Priscilla Vásquez, Isabela Marques, Yuliana Soto, Gabriela Hernandez, Maribel Lopez, Mariel Rancel, Daniel Garcia, Janet Page, Maricela Martinez, and Stephanie Jara.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the University of Illinois at Chicago Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition and the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

References

- 1. ACL. A Statistical Profile of Older Hispanic Americans Aged 65+. https://www.acl.gov/aging-and-disability-in-america/data-and-research/minority-aging. Updated April 4, 2017. Accessed June 27, 2017.

- 2. Hispanics/Latinos and Alzheimer’s disease. 2004. www.alz.org/national/documents/report_hispanic.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2017.

- 3. Clark CM, DeCarli C, Mungas D, et al. Earlier onset of Alzheimer disease symptoms in Latino individuals compared with Anglo individuals. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(5):774–778. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.5.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A, Jagust WJ. Prevalence of dementia in older latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(2):169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petersen RC, Caracciolo B, Brayne C, Gauthier S, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L. Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. J Intern Med. 2014;275(3):214–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Vonsattel JP, Mayeux R. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(4):494–506. doi:10.1002/ana.21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tampi Tampi DJ, Chandran S, Ghori A, Durning MRR. Mild cognitive impairment: a comprehensive review. Heal Aging Res. 2015;4:39. doi:10.12715/har.2015.4.39. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1027–1037. doi:10.1001/jama.300.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(2):125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report, 2008. To the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Part A: executive summary. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(2):114–120. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marquez DX, Neighbors CJ, Bustamante EE. Leisure time and occupational physical activity among racial or ethnic minorities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(6):1086–1093. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c5ec05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Hispanic Community Health Study Data Book; 2013. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/resources/NHLBI-HCHSSOL-English-508.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2017.

- 13. Melillo KD, Williamson E, Houde SC, Futrell M, Read CY, Campasano M. Perceptions of older Latino adults regarding physical fitness, physical activity, and exercise. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27(9):38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cromwell SL, Berg JA. Lifelong physical activity patterns of sedentary Mexican American women. Geriatr Nurs. 2006;27(4):209–213. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16948201. Accessed June 27, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Belza B, Walwick J, Shiu-Thornton S, Schwartz S, Taylor M, LoGerfo J. Older adult perspectives on physical activity and exercise: voices from multiple cultures. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1(4):A09. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15670441. Accessed June 27, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gonzalez A, Delgado CF, Munoz JE. Everynight life: culture and dance in Latin/o America. Danc Res J. 1998;30(2):74. doi:10.2307/1478840. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lewis D. ; Society of Dance History Scholars (US). Conference. Dance in Hispanic Cultures. Yverdon, Switzerland: : Harwood Academic Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kattenstroth JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2013.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guzmán-García A, Hughes JC, James IA, Rochester L. Dancing as a psychosocial intervention in care homes: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):914–924. doi:10.1002/gps.3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karpati FJ, Giacosa C, Foster NE, Penhune VB, Hyde KL. Dance and the brain: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1337:140–146. doi:10.1111/nyas.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hwang PW, Braun KL. The effectiveness of dance interventions to improve older adults’ health: a systematic literature review. Altern Ther Health Med. 2015;21(5):64–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marquez DX, Bustamante EE, Aguinaga S, Hernandez R. BAILAMOS: development, pilot testing, and future directions of a Latin dance program for older Latinos. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(5):604–610. doi:10.1177/1090198114543006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Judge JO. Balance training to maintain mobility and prevent disability. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(3 suppl 2):150–156. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14552939. Accessed June 27, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Robinson TN, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, et al. Dance and reducing television viewing to prevent weight gain in African-American girls: the Stanford GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(1 suppl 1):S65–S77. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12713212. Accessed June 27, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Pike KC, Teri L. Making physical activity accessible to older adults with memory loss: a feasibility study. Gerontologist. 2009;49(suppl 1):S94–S99. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Logsdon RG, Pike KC, McCurry SM, et al. Early-stage memory loss support groups: outcomes from a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65(6):691–697. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGough EL, Kelly VE, Logsdon RG, et al. Associations between physical performance and executive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: gait speed and the timed “up & go” test. Phys Ther. 2011;91(8):1198–1207. doi:10.2522/ptj.20100372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bouchard CE, Shephard RJ, Stephens TE. Physical Activity, Fitness, and Health: International Proceedings and Consensus Statement. Paper presented at: International Consensus Symposium on Physical Activity, Fitness, and Health; May 2, 1992; Toronto, Ontario: Human Kinetics Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. 1997. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellison J, Jandorf L, Duhamel K. Assessment of the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) among low-income, immigrant Hispanics. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(3):478–483. doi:10.1007/s13187-011-0233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gardiner PA, Eakin EG, Healy GN, Owen N. Feasibility of reducing older adults’ sedentary time. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):174–177. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hardy CJ, Rejeski WJ. Not what, but how one feels: the measurement of affect during exercise. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989;11(3):304–317. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borg G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Champaign, IL: Human kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Heal Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Low LF, Carroll S, Merom D, et al. We think you can dance! A pilot randomised controlled trial of dance for nursing home residents with moderate to severe dementia. Complement Ther Med. 2016;29:42–44. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guzmán-García AMukaetova-Ladinska E, James I. Introducing a Latin ballroom dance class to people with dementia living in care homes, benefits and concerns: a pilot study. Dementia (London). 2013;12(5):523–535. doi:10.1177/1471301211429753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van Uffelen JZ, Chinapaw MJ, van Mechelen W, Hopman-Rock M. Walking or vitamin B for cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment? A randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(5):344–351. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.044735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu JJ, Sun MY, Liang LC, Feng Y, Pan XY, Liu Y. Effects of momentum-based dumbbell training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;11:9–16. doi:10.2147/cia.s96042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Division of Planning Research and Development, Illinois Department on Aging. Older Adult Services Overview. Illinois, IL; 2004. https://www.illinois.gov/aging/CommunityServices/Documents/oasa_presentation.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leveille SG, Jones RN, Kiely DK, et al. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and the occurrence of falls in an older population. JAMA. 2009;302(20):2214–2221. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pekmezi DW, Neighbors CJ, Lee CS, et al. A culturally adapted physical activity intervention for Latinas: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):495–500. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(26):1701–1707. doi:10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Calvo-Merino B, Jola C, Glaser DE, Haggard P. Towards a sensorimotor aesthetics of performing art. Conscious Cogn. 2008;17(3):911–922. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Freeston GA, Hughes RL, James I. Psychomotor Dance Therapy Intervention (DANCIN) for people with dementia in care homes: a multiple-baseline single case study. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2016;28(10):1695–1715. doi:10.1017/S104161021600051X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. US Department of Health & Human Services. National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease: 2015 Update | ASPE. 2015. https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-plan-address-alzheimers-disease-2015-update. Updated July 13, 2015. Accessed June 27, 2017.