Abstract

We investigated vascular functioning in patients with a clinical and radiological diagnosis of either Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or vascular dementia (VaD) and examined a possible relationship between vascular function and cognitive status. Twenty-seven patients with AD, 23 patients with VaD, and 26 healthy control patients underwent measurements of flow-mediated dilation (FMD), ankle–brachial index (ABI), cardioankle vascular index (CAVI), and intima–media thickness (IMT). The FMD was significantly lower in patients with AD or VaD compared to controls. There were no significant differences in ABI, CAVI, or IMT among the 3 groups. A significant correlation was found between Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores and FMD. Furthermore, a multiple regression analysis revealed that FMD was significantly predicted by MMSE scores. These results suggest that endothelial involvement plays a role in AD pathogenesis, and FMD may be more sensitive than other surrogate methods (ABI, CAVI, and IMT) for detecting early-stage atherosclerosis and/or cognitive decline.

Keywords: flow-mediated dilation, endothelial function, arterial stiffness, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disorder with an insidious onset and is the most common type of dementia. Despite extensive research, the exact mechanism underlying AD pathogenesis is still unclear. The most accepted hypothesis proposes that amyloid beta (Aβ) protein deposition leads to neurodegeneration. 1,2 Amyloid beta is thought to contribute to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species resulting in oxidative stress, neuronal damage, and cognitive decline. 2 Recent epidemiological studies have shown that vascular risk factors increase risk of both AD and vascular dementia (VaD). 3 –6 Although these findings suggest that vascular factors are associated with AD pathogenesis, results regarding vascular functioning (eg, endothelial functioning or arterial stiffness) remain inconsistent. Some authors 7 –10 have reported vascular dysfunction in AD or vascular function differences between these two dementia groups; however, others 11 –13 have shown neither vascular dysfunction in AD nor differences between the 2 dementia groups. These inconsistent results may be partly due to the use of different measures to assess vascular function. Conversely, some studies have reported a correlation between endothelial function 7 or arterial stiffness 10 and cognitive status.

The present study was designed to investigate vascular functioning with several measurements and compare patients with AD or VaD and healthy controls. In addition, we also examined a possible relationship between vascular function and cognitive status. To evaluate vascular functioning, we measured the brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD), ankle–brachial index (ABI), and cardioankle vascular index (CAVI). We also quantified intima–media thickness (IMT) of the common carotid artery (CCA). The FMD is known to be endothelial dependent and serves as a measure of endothelial vasodilator function in humans. 7,14 The ABI and CAVI are noninvasive clinical methods for detecting arterial stiffness or arteriosclerotic pathologies. 15 –17 The IMT measurements can detect morphological changes in the carotid artery, including intimal atherosclerotic process and medial hypertrophy. 18,19

Methods

Participants

Patients with AD or VaD who visited Kobe University Hospital between November 2013 and February 2015 were consecutively enrolled in this study. A clinical diagnosis of AD was made in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) 20 and/or National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) 21 criteria; cranial computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence excluded most other potential causes of dementia. The VaD was diagnosed using the DSM-V 20 and/or National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN) 22 criteria as well as cranial CT or MRI evidence of relevant cerebrovascular changes. Blood screening tests at the time of diagnosis were performed to exclude metabolic causes of cognitive impairment. General cognitive functioning in all patients (27 patients with AD, 23 patients with VaD, and 26 controls) was evaluated using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). 23 Control patients were enrolled between November 2013 and February 2015 from patients who were healthy; intellectually active; and without any history of neurological dysfunction, cerebrovascular, or cardiovascular diseases. They were employees of our hospital or relatives or spouses of patients. Each control patient scored at least a 26 on the MMSE (mean 28.5, range 26-30). Cardiovascular risk factors, such as the presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking, and previous stroke were ascertained through interviews conducted by neurologists on the basis of the guidelines. 24 –26 Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, self-reported history of hypertension, or current use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood sugar ≥126 mg/dL, self-reported diabetes history, or use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medication. Dyslipidemia was defined as total serum cholesterol ≥220 mg/dL, total serum triglyceride ≥150 mg/dL, self-reported history of dyslipidemia, or current lipid-lowering treatment. Smoking was defined by current smoking or history of tobacco use at any time. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) / height (m2). Obesity was defined as BMI ≥25. Written informed consent was obtained from all study patients after the procedure had been fully explained to the patients and/or their caregivers. The human research ethics committees at Kobe University Hospital approved the protocol, and this study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurement of FMD

Endothelial function was assessed using the FMD test in the right forearm brachial artery based on previously established guidelines. 27 The FMD was performed with a specialized machine using a 10-MHz linear array transducer probe (Unex Co Ltd, Nagoya, Japan). Patients were required to fast for 6 hours and refrain from smoking, exercise, and vasoactive medications before the vascular assessment. The FMD was measured after patients had rested in a supine position for 10 minutes in a quiet room. Ischemia was induced during right forearm compression for 5 minutes at which pressure is 50 mm Hg higher than systolic blood pressure. Brachial artery images were acquired at a point located about 5 cm proximal to the antecubital fossa. Baseline diameter was determined as the average diameter from the end-diastolic images before cuff inflation. The postoccluded diameter was determined as the average of 3 peaks measured 40 to 60 seconds during the reperfusion phase. The FMD induced by reactive hyperemia was expressed as a relative change from baseline (FMD% = postoccluded diameter − baseline diameter/baseline diameter).

Ankle–Branchial Index and CAVI Measurement

Ankle–Branchial Index and CAVI were measured using the VaSera VS-1500 (Fukuda Denshi Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), with patients resting in a supine position. Cuffs were located on both ankles and upper arms. An electrocardiograph was placed on the sternal angle, and these electrodes were attached to the upper arms. After resting for 10 minutes, measurements were performed irrespective of the technician’s skill, and CAVI was automatically calculated from the following the Bramwell-Hill equation: CAVI = In (Ps/Pd) × 2ρ/ΔP × PWV2, where Ps is the systolic blood pressure (SBP), Pd is the diastolic blood pressure (DBP), ρ is the blood viscosity, ΔP is pulse pressure, and PWV is the pulse wave velocity between the heart and the ankle. The ABI was measured based on the SBP for both the upper (brachial artery) and the lower (tibial artery) BP, and the final value was obtained by dividing the ankle SBP by the brachial SBP. Averages from the right and left scores were used for the ABI and CAVI data.

Measurement of IMT

The IMT of the CCA was assessed using the B-mode ultrasound technique with a ProSound α10 machine (ALOKA Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 7.5-MHz linear array probe. While patients were in a supine position, IMT measurements were performed with their head turned to the contralateral side. The IMT was determined as the distance between the intimal–luminal interface and the medial–adventitial interface at the far wall of the carotid artery, excluding the bifurcation. The mean IMT was calculated as the average of each contiguous site, 1 cm from the bifurcation on the right and left sides, consisting of the max IMT site and each 1-cm distant site from the max IMT. Average IMT scores from the right and left sides were used for the IMT data.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous and categorical variables were calculated as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and percentages, respectively. Continuous variables between the 3 groups were similarly compared using 1-way analyses of variance. Post hoc Tukey’s tests were used to compare differences between any 2 groups, and χ2 tests were used for categorical variables. Pearson’s correlation test was carried out to examine the association between MMSE scores and FMD. To investigate factors influencing FMD, a multiple regression analysis was performed using FMD as the dependent variable and age, gender, obesity, education, smoking status, presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and MMSE scores as independent variables. A P value of .05 or less was considered statistically significant. The statistical package SPSS 22.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois) was used for all data analyses.

Results

Study Patient’s Characteristics

The 3 groups’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Comparison of clinical variables among the 3 groups was performed. There were significant differences in gender (P = .037), MMSE score (P < .001), the rates of diabetes mellitus (P < .001), and smoking (P = .022). The MMSE scores in both AD and VaD groups were lower compared to the healthy controls (P < .001 and P < .001, respectively). The rate of diabetes mellitus was higher in the VaD group compared to the healthy controls (P < .001). The number of males and diabetes mellitus and smoking rates were higher in the VaD group compared to the AD group (P < .05, P < .001, and P < .05, respectively).

Table 1.

Study Patients’ Characteristics.a

| AD (n = 27) | VaD (n = 23) | Controls (n = 26) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 75.6 ± 6.3 | 73.5 ± 11.5 | 72.1 ± 7.5 |

| Gender, male (%) | 8 (29.6)a | 15 (65.2)a | 10 (38.5) |

| Education, years | 11.7 ± 2.4 | 11.8 ± 2.4 | 12.0 ± 2.0 |

| MMSE score | 21.6 ± 3.3 | 21.1 ± 4.8 | 28.5 ± 1.4 |

| Obesity (%) | 4 (14.8) | 4 (17.4) | 3 (11.5) |

| Hypertension (%) | 16 (59.2) | 17 (73.9) | 15 (57.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 3 (11.1)b | 12 (52.2)b,c | 2 (7.7)c |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 6 (22.2) | 6 (26.1) | 4 (15.4) |

| Smoking (%) | 3 (11.1)b | 10 (43.5)b | 5 (19.2) |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; VaD, vascular dementia; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

aValues are mean ± standard deviation or number of patients (percentage).

bSignificant difference between the AD and the VaD groups.

cSignificant difference between the VaD and the control groups.

Vascular Measurements

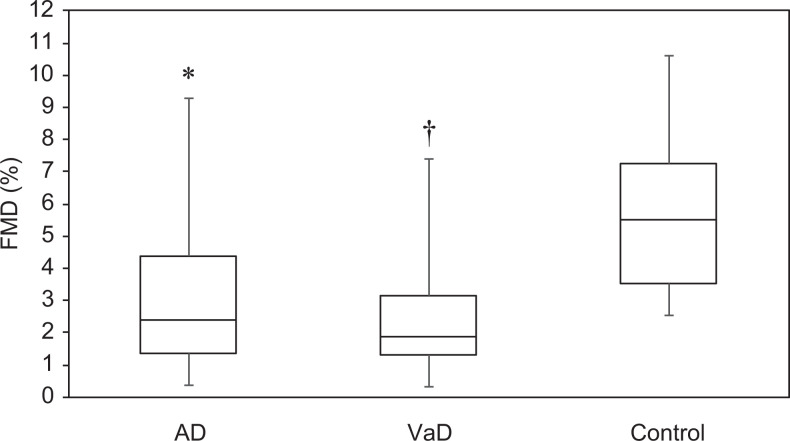

Table 2 shows the vascular measurements for the 3 groups. Both the AD and the VaD groups had lower FMD values than the control group (both P < .001, Figure 1), but no significant difference was noted between the 2 dementia groups. There were no significant differences in ABI, CAVI, or IMT values between the 3 groups.

Table 2.

Study Patients’ Vascular Measurements.a

| AD (n = 27) | VaD (n = 23) | Controls (n = 26) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMD, % | 3.16 ± 2.28b | 2.62 ± 2.07c | 5.94 ± 2.49b,c | <.001 |

| ABI | 1.13 ± 0.07 | 1.11 ± 0.17 | 1.11 ± 0.11 | .296 |

| CAVI | 9.16 ± 1.12 | 9.53 ± 1.34 | 8.88 ± 1.56 | .749 |

| IMT, mm | 0.89 ± 0.23 | 0.89 ± 0.30 | 0.84 ± 0.18 | .832 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; VaD, vascular dementia; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; ABI, ankle-brachial index; CAVI, cardio-ankle vascular index; IMT, intima-media thickness.

aValues are mean ± standard deviation.

bSignificant difference between the AD and control groups.

cSignificant difference between the VaD and control groups.

Figure 1.

Distribution of flow-mediated dilation (FMD) values. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD; P < .001) and vascular dementia (VaD; P < .001) had significantly worse FMD than controls. The black lines within the boxes indicate the median; the bottom and top edges of the boxes are the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively; and the lines extend to the maximum and minimum values. Mean FMD values ± standard deviation: AD group, 3.16% ± 2.28%; VaD group, 2.62% ± 2.07%; control group, 5.94% ± 2.49% (P < .001 compared to both dementia groups). *Significant difference between the AD and the control groups. †Significant difference between the VaD and the control groups.

Relationship Between the FMD and the MMSE

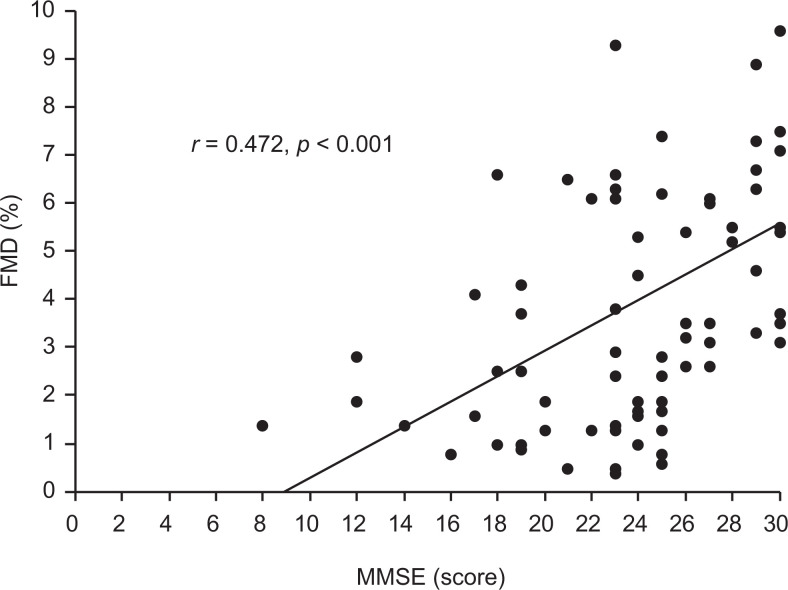

Since only FMD was significantly decreased in the dementia groups, the relationship between FMD and MMSE was examined. When the correlation between MMSE scores and FMD in the total sample (n = 76 including the patients with AD, patients with VaD, and controls) was examined, a positive relationship was observed (P < .001, Figure 2). Subsequent multiple regression analysis showed that FMD was significantly predicted by MMSE score (P = .001; Table 3).

Figure 2.

Correlation between flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score in the total sample (n = 76). FMD was significantly correlated with MMSE score (r = 0.472; P < .001).

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Analysis Result Using Forced Entry Method (Where FMD is a Dependent Variable).

| Predictors | β | SE | t Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.193 | 0.024 | −1.796 | .078 |

| Gender | −0.189 | 0.711 | −1.487 | .142 |

| Obesity | 0.091 | 0.717 | 0.848 | .400 |

| Education | 0.031 | 0.134 | 0.287 | .775 |

| Smoking | 0.096 | 0.772 | 0.799 | .428 |

| Diabetes mellitus | −0.072 | 0.802 | −0.599 | .552 |

| Hypertension | −0.144 | 0.645 | −1.263 | .212 |

| Dyslipidemia | −0.150 | 0.748 | −1.374 | .174 |

| MMSE | 0.374 | 0.063 | 3.399 | .001a |

Abbreviation: FMD, flow-mediated dilation; SE, standard error; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

aSignificance at .001.

Discussion

The major finding of our study was decreased FMD in both patients with AD and patients with VaD. Vascular risk factors such as age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, and obesity are known to be associated with oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. 2,28 The FMD is decreased in patients with vascular risk factors, even those without clinical atherosclerosis. 29 However, the present findings suggest that endothelial function could be impaired in AD, which may indicate a systemic element of AD pathology independent of vascular risk factors. This is because there were no differences in risk factors between the AD and the control groups (Table 1). Although several studies have investigated a relationship between vascular tone regulation and AD, the published results are inconsistent. 7 –13 Dede et al 7 evaluated endothelial function in patients with AD and reported significantly lower FMD values in patients with AD compared to normal controls, which is consistent with our findings. Dede and colleagues found endothelial dysfunction in patients with AD who did not have vascular risk factors or diseases. The Aβ can interact with vascular endothelial cells to produce an excess of free radicals, 30 which are toxic to both cerebral and peripheral endothelia. 31 These findings suggest that Aβ may directly or indirectly cause neuronal cell loss, leading to lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species; impaired vascular endothelium may also accelerate this phenomenon. 7 Cholinergic denervation is a representative pathological change in the AD brain and may also contribute to endothelial dysfunction without vascular risk factors in AD groups due to repressed production of nitric oxide from endothelial cells 32 that result in decreasing cerebrovascular vasoreactivity.

In the present study, patients with VaD also showed decreased FMD compared to healthy controls. Decreased FMD has been reported in patients experiencing stroke 2,33 and may reflect the cumulative deleterious effects of multiple risk factors on vasoconstriction. Although there are some differences regarding the presence of diabetes mellitus between patients with VaD and controls, our multiple regression analysis showed that FMD was not significantly predicted by the presence of diabetes mellitus. These findings also indicate some degree of endothelial dysfunction in patients with VaD. The results seem to suggest that AD and VaD have peripheral vasomotor effects. There is currently no effective method for measuring endothelial function in the cerebral circulation. 2 However, endothelial function has been explained using peripheral artery FMD in several studies.

Brachial FMD has been associated with the severity of white matter hyperintensities on brain MRI in elderly patients with cardiovascular disease, indicating a relationship between peripheral and cerebral circulation. 34 In addition, an experimental study showed that cerebral vessels respond to acetylcholine infusion similar to peripheral vessels. 12 These lines of evidence suggest that determining endothelial function based on peripheral arteries is a useful indirect measure of the brain’s vascular endothelium status. 7

We did not observe significant differences in arterial stiffness between the AD and the VaD groups. In this regard, the arterial stiffness results between dementia groups in other studies were also inconsistent. Dhoat et al 13 showed reduced central arterial compliance and an increased augmentation index in patients with VaD, indicating that the disease process is associated with diminished vascular compliance of large elastic arteries in these patients; however, this was not the case for patients with AD. Furthermore, the use of central arterial compliance and augmentation index did not provide supporting evidence for vascular disease in AD. 13 On the contrary, Scuteri et al 35 showed that worsening arterial stiffness, as measured by the PWV, was more evident in patients with cortical atrophy than in patients with subcortical microvascular lesions or controls. Some investigators 36 used CAVI and reported impaired arterial stiffness in nonvascular dementia. The inconsistent results in the literature may partly be due to variable measurement methods, differences in VaD subtypes and prevalence rates of vascular risk factors, and/or cognitive dysfunction severity.

The results revealed that FMD and MMSE scores were significantly correlated independent of any vascular risk factors. Dede et al 7 also showed a significant correlation between FMD and the clinical dementia rating (CDR) score for a total sample that included patients with AD and controls. The correlation between cognitive impairment and arterial stiffness, as measured by the PWV, has also been observed by other groups. 10,31,36 Hanon et al 10 reported a relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive impairment in a sample that included patients with AD, patients with VaD, and controls, suggesting that functional changes in the arterial system could be involved in dementia onset. The present findings suggest that endothelial functioning may also be more impaired when MMSE scores are worse, indicating that endothelial dysfunction per se is related to cognitive impairment. Gonzales et al 37 showed that FMD was significantly related to reduced working memory-related activation in the right superior parietal lobe, suggesting a relationship between peripheral FMD and cerebrovascular responses to cognition. These findings could also indicate a relationship between cognition and endothelial dysfunction.

This study did not demonstrate any differences in ABI, CAVI, or IMT between the AD, VaD, and control groups. Although FMD, ABI, CAVI, and IMT may be surrogates of atherosclerotic disease processes, these methods measure different aspects and stages of early atherosclerosis. A lower ABI is associated with more atheromatous lesions, higher IMT, and greater carotid stenosis. 38 Decreased FMD is associated with carotid plaques. 39 However, patients with reduced FMD do not necessarily show increased IMT. Yan et al 40 reported that there was no significant correlation between FMD and carotid IMT in healthy middle-aged men. Although the endothelium appears to play an important role in arterial stiffness, structural changes in the vessel wall are a major component of arterial stiffness. Endothelial dysfunction is a fundamental step in the atherosclerotic disease process, and FMD is reported to be one of the early mechanisms of atherosclerosis. 2 Thus, the present results suggest that FMD evaluation is more sensitive than other surrogate markers (eg, ABI, CAVI, and IMT) for detecting atherosclerosis.

The present study has some limitations. A desired control for the case–control study should be as close in features as the case except for the disease under study. In this aspect, the patients should have been age, gender, and education matched, although there was a significant difference in gender among the 3 groups in this study. Another limitation is the relatively small number of patients. This study was not population based and there are therefore unknown bias in selection. Some predictors may come insignificant because of the inadequate sample size. Larger study is needed to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, endothelial dysfunction appears to play a significant role in AD pathogenesis, and FMD may be more sensitive than other surrogate markers for detecting early-stage atherosclerosis and/or cognitive decline. The data from this study suggest that FMD is reduced in patients with cognitive impairment. Whether treatments aimed at increasing FMD can improve patient prognoses needs to be determined in future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients who were invited to attend this study.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256(5054):184–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelleher RJ, Soiza RL. Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in the development of Alzheimer’s disease: is Alzheimer’s a vascular disorder? Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;3(4):197–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Launer LJ, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, et al. Midlife blood pressure and dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(1):49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fratiglioni L, Winblad B, Von Strauss E. Prevention of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Major findings from the Kungsholmen Project. Physiol Behav. 2007;92(1-2):98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pansari K, Gupta A, Thomas P. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular factors: facts and theories. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(3):197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kaffashian S, Dugravot A, Elbaz A, et al. Predicting cognitive decline: a dementia risk score vs. the Framingham vascular risk scores. Neurology. 2013;80(14):1300–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dede DS, Yavuz B, Yavuz BB, et al. Assessment of endothelial function in Alzheimer’s disease: is Alzheimer’s disease a vascular disease? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(10):1613–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khalil Z, LoGiudice D, Khodr B, Maruff P, Masters C. Impaired peripheral endothelial microvascular responsiveness in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11(1):25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Algotsson A, Nordberg A, Almkvist O, Winblad B. Skin vessel reactivity is impaired in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(4):579–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanon O, Haulon S, Lenoir H, et al. Relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive function in elderly subjects with complaints of memory loss. Stroke. 2005;36(10):2193–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bari F, Toth-Szuki V, Domoki F, Kalman J. Flow motion pattern differences in the forehead and forearm skin: age-dependent alterations are not specific for Alzheimer’s disease. Microvasc Res. 2005;70(3):121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McGleenon BM, Passmore AP, McAuley DF, Johnston GD. No evidence of endothelial dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11(4):197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dhoat S, Ali K, Bulpitt CJ, Rajkumar C. Vascular compliance is reduced in vascular dementia and not in Alzheimer’s disease. Age Ageing. 2008;37(6):653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patel S, Celermajer DS. Assessment of vascular disease using arterial flow mediated dilation. Pharmacol Rep. 2006;suppl 58:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shirai K, Utino J, Otsuka K, Takata M. A novel blood pressure-independent arterial wall stiffness parameter; cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI). J Atheroscler Thromb. 2006;13(2):101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sorokin A, Kotani K, Bushueva O, Taniguchi N, Lazarenko V. The cardio-ankle vascular index and ankle-brachial index in young Russians. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22(2):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakamura K, Tomaru T, Yamamura S, Miyashita Y, Shirai K, Noike H. Cardio-ankle vascular index is a candidate predictor of coronary atherosclerosis. Circ J. 2008;72(4):598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kobayashi K, Akishita M, Yu W, Hashimoto M, Ohni M, Toba K. Interrelationship between non-invasive measurements of artherosclerosis: flow-mediated dilation of brachial artery, carotid intima-media thickness and pulse wave velocity. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173(1):13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miwa K, Hoshi T, Hougaku H, et al. Silent cerebral infarction is associated with incident stroke and TIA independent of carotid intima-media thickness. Intern Med. 2010;49:817–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on diagnostic guideline for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Román GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular dementia. Diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43(2):250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kario K. Key points of the Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension in 2014. Pulse (Basel). 2015;3(1):35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kashiwagi A, Kasuga M, Araki E, et al. ; Committee on the Standardization of Diabetes Mellitus – Related Laboratory Testing of Japan Diabetes Society. International clinical harmonization of glycated hemoglobin in Japan: from Japan Diabetes Society to National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program values. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3(1):39–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ueshima H, et al. ; Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Committee for Epidemiology and Clinical Management of Atherosclerosis. Diagnostic criteria for dyslipidemia. Executive summary of Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Guideline for Diagnosis and Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases for Japanese. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2007;14(4):155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(2):257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roquer J, Segura T, Serena J, Castillo J. Endothelial dysfunction, vascular disease and stroke: the ARTICO study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(suppl 1):25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Campuzano R, Moya JL, García-Lledó, et al. Endothelial dysfunction, intima-media thickness and coronary reserve in relation to risk factors and Framingham score in patients without clinical atherosclerosis. J Hypertens. 2006;24(8):1581–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas T, Thomas G, McLendon C, Sutton T, Mullan M. beta-Amyloid-mediated vasoactivity and vascular endothelial damage. Nature. 1996;380(6570):168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sutton ET, Hellermann GR, Thomas T. beta-Amyloid-induced endothelial necrosis and inhibition of nitric oxide production. Exp Cell Res. 1997;230(2):368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosengarten B, Paulsen S, Molnar S, Kaschel R, Gallhofer B, Kaps M. Acetylcholine esterase inhibitor donepezil improves dynamic cerebrovascular regulation in Alzheimer patients. J Neurol. 2006;253(1):58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sunbul M, Ozben B, Durmus E, et al. Endothelial dysfunction is an independent risk factor for stroke patients irrespective of the presence of patent foramen ovale. Herz. 2013;38(6):671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoth KF, Tate DF, Poppas A, et al. Endothelial function and white matter hyperintensities in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Stroke. 2007;38(2):308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scuteri A, Brancati AM, Gianni W, Assisi A, Volpe M. Arterial stiffness is an independent risk factor for cognitive impairment in the elderly: a pilot study. J Hypertens. 2005;23(6):1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nagai K, Akishita M, Machida A, Sonohara K, Ohni M, Toba K. Correlation between pulse wave velocity and cognitive function in nonvascular dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(6):1037–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gonzales MM, Tarumi T, Tanaka H, et al. Functional imaging of working memory and peripheral endothelial function in middle-aged adults. Brain Cogn. 2010;73(2):146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Allan PL, Mowbray PI, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG. Relationship between carotid intima-media thickness and symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. The Edinburgh Artery Study. Stroke. 1997;28(2):348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rundek T, Hundle R, Ratchford E, et al. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with carotid plaque: a cross-sectional study from the population based Northern Manhattan Study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006;6:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yan RT, Anderson TJ, Charbonneau F, Title L, Verma S, Lonn E. Relationship between carotid artery intima-media thickness and brachial artery flow-mediated dilation in middle-aged healthy men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(12):1980–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]