Abstract

Subjective cognitive complaints (SCCs) are frequent in the elderly population. The majority of individuals with subjective complaints never progress to significant cognitive decline, but some of them have a higher risk of progression to objective cognitive impairment than persons with no cognitive concerns. We performed a systematic review of community-based studies that focused on the progression risk associated with SCC and on the complainers’ characteristics associated with progression. Seventeen studies were included. As a group, SCCs are associated with a significantly higher risk of progression to dementia. Worried complainers, persons who refer an impact of their complaints on activities of daily living, and those whose complaints are also noticed by an informant have the highest risk of progression. Taking into account the fluctuating course of SCC and their frequent reversion, care should be taken to not overvaluate them. Further studies are necessary to better define risk features.

Keywords: subjective cognitive complaints, subjective memory complaints, dementia, Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, systematic review

Introduction

Subjective cognitive complaints (SCCs) are cognitive concerns of people who may or may not have deficits in objective testing. 1 Large community-based studies have pointed to a prevalence in the order of 50% 2 to 60% 3 in older adults which increases with age. 4 Fear of incipient dementia is frequent in elders with SCC. 5 As such, the determination of the precise outlines of the relationship between SCC and dementia has become very important to clinical practice. 5

Metacognition, the awareness of the functioning of one’s own cognition, differs between participants. 6,7 Deficit awareness may be an early manifestation of a dementing illness, but the self-perception of the deficits often fails to align with objective memory problems, with a variety of psychological, environmental, and pathological factors influencing SCC. 6

Definition of SCC has been unspecific. The SCCs are related to numerous conditions such as normal aging, personality traits, and neuropsychiatric disorders, hindering a proper operationalization. The reported experience of cognitive decline has had many names: subjective cognitive impairment, subjective memory decline, and subjective memory impairment (SMI), among other terminologies. 8 Also, different strategies are applied to assess individuals in distinct environments. To uniformize and improve the understanding of SCC, the subjective cognitive decline initiative (SCD-I) was started and recently proposed core criteria for subjective cognitive decline. 9 A set of recommendations for the use of these criteria in dementia research were also provided.

Individuals with SCC constitute a heterogeneous group. The great majority of them are “worried well” and don’t deteriorate more rapidly than usual. 1,10,11 The disappearance of the subjective sensation of cognitive decline is common. 12 Nevertheless, some participants with SCC have evidence of preclinical Alzheimer disease (AD) and, as such, a higher risk of progression to dementia. 13

The SCCs were included in the early definitions of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Interestingly, many studies have failed to find a relationship between subjective and objective deficits, and further research showed SCC to be neither necessary nor sufficient for the diagnosis of MCI. 4 Considerable debate exists about the relationship between objective testing and SCC. Nonetheless, MCI and SCC are still somewhat overlapping constructs, and this fact probably contributed to delay research on SCC without cognitive impairment.

A recent meta-analysis suggested that older people with subjective memory complaints (SMC) but no objective deficits are twice as likely to develop dementia as individuals without SMC. 1 To our knowledge, this is the only systematic review to date on the participant. It included both community and memory clinic-based samples.

Memory complainers who seek medical attention have higher rates of daily functioning deterioration, worries, and family history of dementia. 14 Some of these characteristics are related to a higher risk of subsequent cognitive impairment, probably leading to a different risk of progression to dementia between community and memory clinic complainers. Even as some characteristics associated with higher risk of objective impairment were identified, it remains unclear what are the complainers’ features associated with progression risk in community-based samples—it is not yet known how to identify the complainers in whom SCCs are a manifestation of a neurodegenerative process and not a functional problem (as depression). 15 The identification of at-risk persons provides a unique opportunity for early intervention trials, 16 and it is desirable due to the anticipated advent of disease-modifying treatments. 17

Community-based studies avoid the potential bias from higher risk memory clinic samples. To our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews focusing only on community-based studies. Trying to address this gap, we conducted a systematic review of recent longitudinal community-based studies that evaluated SCC as a risk factor for MCI and dementia and tried to identify cognitive complainers’ characteristics related to progression.

Methods

Data Source

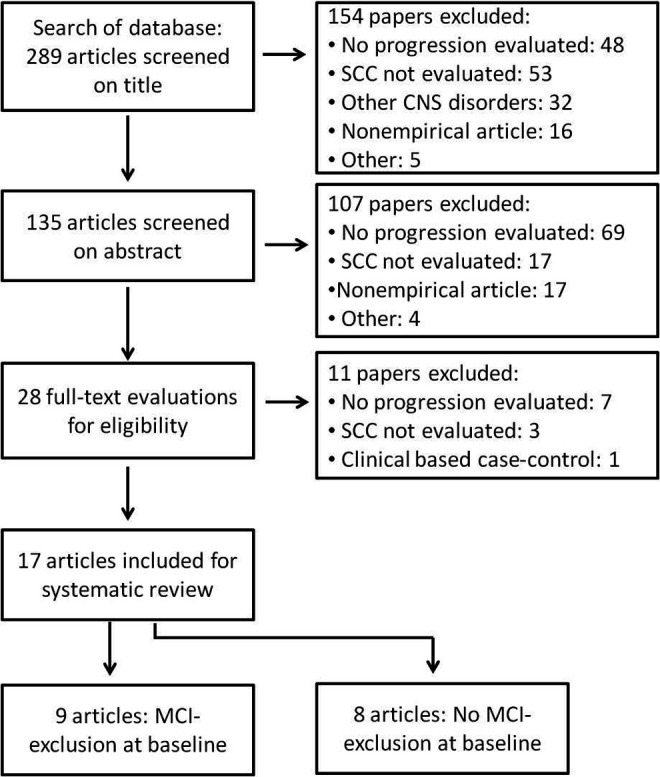

We performed a comprehensive literature review on PubMed for references published between January 2008 and April 2014. Although the time period can be considered arbitrary, in the absence of an objective time boundary, the authors considered the chosen period to contain the most updated and relevant information on the participants. The search strategies used both medical subject heading terms when available and text words related to SCC, MCI, and dementia. A combination of the following terms was used: subjective, memory, cognitive, cognition, complaints, impairment, deficit, failure, dysfunction, or decline, and added to the words longitudinal, progress*, predict*, declin*, develop*, prospect*, Alzheimer*, or dementia. Articles were screened for eligibility according to criteria predefined by 1 of the authors (MM). The article selection data are summarized in Figure 1. The search was restricted to articles written in English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish language.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection strategy.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were (1) longitudinal community-based studies (either prospective or retrospective) that evaluated the role of SCC as a risk factor for incident MCI or dementia, (2) participants older than 18 years of age, (3) outcome presented as a measure of risk (odds ratio, hazard ratio, or relative risk) or in a way that a crude approximation of risk could be inferred, and (4) follow-up time of at least 24 months. Exclusion criteria were (1) studies that evaluated the presence of SCC in the context or as a consequence of any central nervous system disorder (such as stroke, Parkinson disease, bipolar disorders and so on) and (2) studies that did not specify any clear definition of SCC/SMC/SMI, cognitive impairment, MCI, and/or dementia.

Data Extraction

Studies’ details were extracted using a previously designed form. When available, adjusted measures of risk were collected together with the indication of the variables that were controlled for.

Results

General Characteristics

A total of 289 articles were identified. Seventeen studies were included (flowchart in Figure 1). In 9 studies, no participant had objective cognitive deficit compatible with MCI or dementia at inclusion (Table 1). The other studies did not clearly exclude individuals based on their objective cognitive performance at baseline, or, if they did, exclusion of MCI was not guaranteed (Table 2). The samples are heterogeneous concerning participants’ age (59-81 years) and education. Tables 1 and 2 provide an overview of the studies’ characteristics. Adjustment variables for each study are summarized in Table 3.

Table 1.

Studies Evaluating Cognitive Deterioration in Patients With SCC and No Objective Cognitive Deficit Compatible With MCI or Dementia At Baseline.a

| Study | Population at Inclusion | Groups at Follow-Up | Age, Mean (SD) | Follow-Up Time, Mean (SD) | End Point | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donovan et al 18 | MADRC cohort. Sample of 599 participants | No complaints: 283 | 69.6 (9.8) | 2.43 (1.0) | % that converted to MCI or dementia. | 7.8% |

| SCC: 56 | 76.4 (6.5) | 30% | ||||

| Gifford et al 19 | NACC UDS cohort. Sample of 6261 participants | No complaints: 3300 | 72.6 (8.2) | 3.5 (1.8) | OR (99% CI) of conversion to MCI or dementia | 9% |

| Self-complaints: 656 | 72.7 (8.4) | 2.1 (1.5-2.9) | ||||

| Informant complaints: 139 | 73.9 (8.4) | 2.2 (1.2-3.9) | ||||

| Self- and informant complaints: 319 | 72.8 (7.4) | 4.2 (2.9-6.0) | ||||

| Caselli et al 20 | Arizona ApoE cohort. Sample of 447 participants | Self-reported complaints: 137 | 59.0 (7.4) | 6.7 (4.8) | OR of conversion to MCI | 2.78 |

| Informant-reported complaints: 117 | 4.58 | |||||

| Jessen et al 21 | AgeCoDe cohort. Sample of 3327 participants | No complaints: 863 | 79.7 (3.5) | 6 | relative risk (RR) (95% CI) of conversion to AD dementia | 3.7% |

| Subjective memory impairment: 1061 | 79.8 (3.5) | 1.55 (1.02-2.37) | ||||

| Concerned complainers | 2.44 (1.44-4.14) | |||||

| Not concerned | 1.25 (0.79-2.00) | |||||

| Sargent-Cox et al 22 | PATH through life study. Sample of 2551, 60 to 64-year-old patients | No cognitive impairment: 2082 | 62.5 | 4 | OR (95% CI) of progression to MCI associated with memory problems | 0.18 (0.02-1.37) |

| OR (95% CI) of progression to MCI associated with memory interference | 3.78 (1.32-10.82) | |||||

| Jessen et al 17 | AgeCoDe cohort. Sample of 3327 participantsb | No complaints at baseline and no MCI at follow-up 1: 766 | 79.3 (3.3) | 3 | OR (95% CI) of conversion to dementia | 1.6% |

| No complaints at baseline and MCI at follow-up 1: 108 | 79.8 (3.1) | 4.41 (1.44-13.48) | ||||

| SMI at baseline and no MCI at follow-up 1: 1025 | 79.5 (3.7) | 2.22 (0.97-4.97) | ||||

| SMI at baseline and amnestic MCI at follow-up 1: 21 | 79.8 (4.1) | 29.24 (8.75-97.78) | ||||

| SMI at baseline and nonamnestic MCI at follow-up 1: 155 | 80.4 (3.7) | 6.26 (2.41-16.28) | ||||

| Reisberg et al 23 | 260 community-dwelling persons, older than 40 years, recruited by referral or public announcement | No cognitive impairment (NCI): 47 | 64.1 (8.9) | 10.7 (3.6) | % of conversion to MCI or dementia | 14.9% |

| SCI: 166 | 67.5 (8.9) | 7.7 (3.5) | 54.2% | |||

| Luck et al 24 | LEILA 75+ study. 1500 subjects recruited. 732 at risk of MCI | No cognitive impairment: 463 | 81.0 (4.5) | 8 | HR (95% CI) of progression to MCI diagnosed according consensus criteria | 1.92 (1.28-2.88) |

| Luck et al 25 | AgeCoDe cohort. Sample of 3327 participants | No cognitive impairment: 2331 | 79.5 | 2.5 | OR (95% CI) of conversion to MCI diagnosed according consensus criteria | 1.42 (1.11-1.81) |

Abbreviations: SCC , Subjective cognitive complaint; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; SMI, subjective memory impairment; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AD, Alzheimer disease.

aMassachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (MADRC) longitudinal cohort, established in 2005, recruited patients through community and speciality clinics. National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) longitudinal cohort in 2005 implemented the Uniform Data Set (UDS), a standard evaluation protocol applied in the 34 national Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADC). The NACC is not a population based, but a referral-based or volunteer case series depending on the criteria of each ADC. They tend to be highly educated volunteer research participants. German Study on Aging, Cognition and Dementia in primary care patients (AgeCoDe) is a general practice registry study, from 6 centers (Hamburg, Bonn, Düsseldorf, Leipzig, Mannhein, and Munich). It included patients older than 75 years, absence of dementia according to general practitioner (GP) judgment, and at least 1 contact with the GP in the last 12 months. Personality and Total Health (PATH) through life study is a population-based study. Patients were residents in Canberra and Queanbeyan, Australia, and were recruited randomly through the electoral roll. It includes 2551 individuals aged 60 to 64. It plans to be a 20-year cohort. Leipzig Longitudinal Study of the Aged (LEILA) identified, by systematic random sampling, 1500 individuals aged 75 years and older who lived in the community of Leipzig-South. They were selected from an age-ordered list provided by the official registry office. Institutionalized individuals were included by proportion. Arizona ApoE cohort recruited cognitively normal resident of Maricopa County aged 45 to 79 years with a family history of dementia through local media ads for a longitudinal study of cognitive aging.

bSMI without worry was associated with a risk of 1.83 (1.12-2.99) and SMI with worry with a risk of 3.53 (2.07-6.03).

Table 2.

Studies Evaluating Cognitive Deterioration in Nondemented Patients With SCC at Baseline, Without Proper Exclusion of MCI at Baseline.a

| Study | Population at Inclusion | Groups | Age, Mean (SD) | Follow-Up Time, Mean (SD) | End Point | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeung et al 26 | MSHA cohort. Sample of 2890 participants | 990 participants. 19.6% with Subjective Memory Loss (SML) | 75.9 (6.3) | 5 | OR (95% CI) of conversion to dementia | 1.96 (1.20-3.20) | |

| St. John et al 27 | MSHA cohort. Sample of 2890 participants | 1468 participants. 21.3% with SML | 75.4 (6.7) | 5 | OR (95% CI) of conversion to Cognitive Impairment, No Dementia (CIND) | 1.27 (0.75-2.14) | |

| OR (95% CI) of conversion to dementia | 1.67 (1.01-2.75) | ||||||

| Chary et al 28 | Paquid cohort. 3777 participants | 565 participants (low-level education) | 77.1 (5.5) | 3 | OR (95% CI) risk of conversion for each complaint | ||

| During everyday activities | 1.08 (0.62-1.88) | ||||||

| Retaining new simple information | 1.40 (0.80-2.43) | ||||||

| Remembering old memories | 2.55 (1.00-6.55) | ||||||

| Language fluency | 0.80 (0.46-1.39) | ||||||

| 1569 participants (high-level education) | 76.5 (6.4) | During everyday activities | 1.35 (0.94-1.94) | ||||

| Retaining new simple information | 2.50 (1.74-3.59) | ||||||

| Remembering old memories | 1.32 (0.51-3.41) | ||||||

| Language fluency | 1.46 (1.02-2.09) | ||||||

| Chary et al 28 | Paquid cohort. 3777 participants | 390 participants (low-level education) | 75.4 (5.5) | 10 | OR (95% CI) risk of conversion for each complaint | ||

| During everyday activities | 1.22 (0.83-1.79) | ||||||

| Retaining new simple information | 0.97 (0.67-1.40) | ||||||

| Remembering old memories | 1.28 (0.55-2.99) | ||||||

| Language fluency | 1.11 (0.76-1.62) | ||||||

| 1149 participants (high-level education) | 74.5 (5.6) | During everyday activities | 1.47 (1.13-1.91) | ||||

| Retaining new simple information | 1.47 (1.12-1.93) | ||||||

| Remembering old memories | 0.91 (0.44-1.90) | ||||||

| Language fluency | 1.18 (0.91-1.53) | ||||||

| Heser et al 29 | AgeCoDe study. 3327 participantsb | 2663 participants. 51.8% with SMC | 81.2 | 4 | HR (95% CI) of Conversion to Dementia | ||

| All | 1.50 (1.17-1.92) | ||||||

| Concerned | 2.30 (1.68-3.13) | ||||||

| Waldorff et al 30 | All population aged 65+ in Copenhagen inner district. 1180 participants | Participants: 758. 23.3% with SMC | 74.8 | 4 | HR (95% CI) of hospital-based dementia diagnosis. Multivariate analysis | 2.27 (1.26-4.10) | |

| Jessen et al 31 | AgeCoDe study. 3327 participants | Participants: 1526. 59.3% with SMC | 80.1 | 4.5 | HR (95% CI) progression to AD | ||

| SMC without worry | 1.86 (1.04-3.33) | ||||||

| SMC with worry | 3.51 (1.89-6.49) | ||||||

| Jungwirth et al 32 | VITA study. 606 participants | 487 participants | 75.8 | 5 | OR (95% CI) of conversion to probable AD | 1.51 (1.16-1.96) | |

| Jungwirth et al 33 | VITA study. 606 participants | 161 participants (MMSE 23-27) | 75.8 | 2.5 | OR (95% CI) of conversion to probable AD or mixed dementia (AD + vascular dementia | 1.10 (0.86-1.40) | |

| 317 participants (MMSE 28-30) | 75.7 | 1.34 (1.07-1.68) | |||||

Abbreviations: SCC , Subjective cognitive complaint; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AD, Alzheimer disease.

aManitoba Study of Health and Aging (MSHA) is a prospective population-based cohort study of aging and cognition of randomly selected people older than 65 years and living in the community of Manitoba. Personnes Agées QUID (Paquid) is a population-based cohort of 3777 home-living individuals older than 65 years in southwestern France randomly selected from electoral rolls. German Study on Aging, Cognition, and Dementia in primary care patients (AgeCoDe) is a general practice registry study, from 6 centers (Hamburg, Bonn, Düsseldorf, Leipzig, Mannhein, and Munich). It included patients older than 75 years, absence of dementia according to GP judgement and at least 1 contact with the GP in the last 12 months. Vienna Transdanube Aging study (VITA) is a longitudinal population-based cohort study of 75-year-old inhabitants of 2 districts of Vienna (Austria). All 75-year-old residents of the 21st and 22nd municipal districts of Vienna were invited to participate.

bVery late-onset depression in combination with current depressive symptoms was most predictive of AD.

Table 3.

Adjustment Variables for Each Study Included the Multivariable Analysis.

| Age | Sex | Education | Cognitive Testinga | Depression | ApoE | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies included in Table 1 | |||||||

| Donovan et al 18 | No multivariable analysis performed | ||||||

| Gifford et al 19 | X | X | X | X | Xb | ||

| Caselli et al 20 | No multivariable analysis performed | ||||||

| Jessen et al 21 | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Sargent-Cox et al 22 | X | X | X | X | Xc | ||

| Jessen et al 17 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Reisberg et al 23 | No multivariable analysis performed | ||||||

| Luck et al 24 | X | X | X | Xc | |||

| Luck et al 25 | X | X | X | X | Xd | ||

| Studies included in Table 2 | |||||||

| Yeung et al 26 | X | X | X | X | Xe | ||

| St. John et al 27 | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Chary et al 28 | X | X | |||||

| Heser et al 29 | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Waldorff et al 30 | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Jessen et al 31 | X | X | X | X | X | Xf | |

| Jungwirth et al 32 | X | X | |||||

| Jungwirth et al 33 | No multivariable analysis performed | ||||||

Abbreviation: MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

aCognitive testing includes the MMSE or other performed objective evaluation.

bRace and follow-up periods.

cHypertension, diabetes, smoking, and alcohol.

dSmoking and alcohol.

eNumber of spoken languages.

fSmoking.

Studies That Evaluated SCC Evolving to MCI or Dementia (Table 1)

Cohorts’ information

Five studies used population-based samples. Two were referral-based cohorts and 2 voluntary-based cohorts. Detailed cohorts’ information can be found in Table 1.

Definition and assessment of SCC

Subjective cognitive complaints, loss, or impairment were defined in 5 studies 17,21,22,24,25 by a positive answer to any of 2 questions: “do you feel like your memory is becoming worse” or “do you have problems with your memory.” One study used both informant-based and self-based reports to define SMC, 18 and another identified 4 groups based on investigator judgment during an interview: no complaints, self-complaints, and informant complaints in the absence or in the presence of self-complaints. 19 A positive score on the Multidimensional Assessment of Neurodegenerative Symptoms was used as a definition of cognitive complaint by the last one. 20

Risk of MCI or dementia in SCC individuals

Eight of 9 studies found that SCCs were associated with a higher risk of progression to MCI and/or dementia. One study found a nonsignificant increase in the risk of MCI at 4 years. 22

Worried SCC and SCC with deterioration in daily functioning and risk of progression

One study evaluated the role of SCC with impact on daily activities and found, after 4 years of follow-up, an almost 4-fold increase in the risk of MCI. 22 Two studies evaluated the risk in worried complainers and detected a 3.5 higher risk of developing AD after 3 years 17 and 2.5 higher at 6 years of follow-up. 21 Those not concerned with their memory presented only a 1.8 higher risk at 3 years 17 and a nonsignificant difference at 6 years. 21

Self-based and informant-based complaints

When compared to subject-only complaints, the validation of cognitive complaints by an informant doubled the risk of progression to MCI or dementia after 3.5 years. 19 After 6.7 years of follow-up, informant-reported decline was associated with a nearly 5 times higher risk of progression to MCI, while its report by the participant was associated with a 3 times higher risk of progression. 20

Studies That Did Evaluated SCC Without Excluding Objective Cognitive Impairment (Table 2)

Cohorts’ information

Eight studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and did not exclude MCI at baseline. 26 -33 All studies are population based. Detailed cohorts’ information can be found in Table 2.

Definition and assessment of SCC

Six studies 26,27,29 -32 defined SCC, loss, or impairment by a positive answer to a question in the form of “Please tell me if you have had memory loss in the past year. You can just answer yes or no” or “Have you noticed memory loss?” Jessen et al, in the evaluation of complaints, allowed 3 different answers ‘‘no’’, ‘‘yes, but this does not worry me,” and “yes, this worries me.” 31 Chary et al used 4 questions to define SCC (forgetfulness in activities of daily living, difficulty remembering new simple information, in remembering old memories, and difficulties in finding words) and evaluated the individual risk associated with a positive answer to any of these questions. 28 Jungwirth et al 32,33 also assessed subjective memory decline based on a positive answer to any of 4 questions about changes in specific areas of everyday memory.

Risk of progression of SCC to dementia

Mild cognitive impairment was not formally evaluated in any study, so only the risk of progression to dementia was estimated. Two studies 26,27 used the 3MS (Modified Mini-Mental State) test at baseline. It incorporates more tests than the MMSE and is designed to sample a broader variety of cognitive functions. It widens the range of scores from 0 to 100. 26,27 Participants with a normal 3MS score were considered cognitively unimpaired and entered the studies. However, 3MS is not sensitive enough to exclude MCI individuals at baseline. In the other 6 studies, 28 -33 no objective cognitive tests were used to assess MCI at baseline. These 8 studies could thus have included cognitively normal and cognitively impaired participants at baseline. They all consistently showed an increased risk of progression to dementia in individuals with SCC after a follow-up of 3 to 10 years (Table 2).

However, 2 subgroups were identified in whom SMI was not associated with a risk of progression to dementia. 28,31 After a follow-up of 2.5 years, individuals with SMC and a baseline MMSE score of 23 to 27 did not have a significantly higher risk of progression to dementia, when comparing to those with a MMSE score of 28 to 30. 33 Chary et al 28 found that, while in persons with a complete primary education or further studies, the complaint of difficulty in retaining new simple information was associated with an increased risk of progression to dementia at both 3 and 10 years, this was not replicated in participants with less than the primary education.

Worried SCC and risk of progression

Two studies evaluated the risk of progression to dementia associated with worried SMC. Worried complainers had higher risk of progression to dementia than nonworried complainers both at 4 29 and 4.5 31 years of follow-up.

Discussion

Clinicians are frequently confronted with elderly participants who report SCC, including memory problems, such as forgetting appointments in the near future or not remembering details of recent events. 34 The relevance and management of SCC is frequently discussed in the literature, and the hypothesis that SCC might be a preliminary stage of dementia has already led to the development of specific preventive trials. 35 Although there is currently no cure for dementia, timely identification of at-risk participants would allow them to engage in lifestyle and behavioral interventions which have been shown to enhance cognition and decrease conversion. 23 In this systematic review, we revised studies focusing on large community-based samples of dementia-free elderly participants to understand who are the individuals with cognitive complaints that have a higher risk of progression to cognitive deterioration.

Who are the Complainers at Risk of Cognitive Deterioration?

Sixteen from the 17 studies included in this review consistently showed that, in older age participants (59 and older), the presence of SCC is associated with a 1.5- to 3-fold higher risk of progression to MCI or dementia. Twelve studies demonstrated this after adjustment to at least 2 frequent confounding variables, such as age, sex, education, baseline cognitive performance, or depression (Table 3). The only study 19 that did not detect increased risk of progression for individuals with SCC as a whole, did, however, find a subgroup of patients with SCC, with a higher risk of progression to MCI. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the overwhelming majority of individuals with SCC do not experience the occurrence of any objective cognitive decline.

When discussing cognitive decline risk in SCC, some issues should be pointed out. The SCC course over time is quite unstable and unpredictable, and these participants can revert to normal cognition. 36 -38 This same reversion has also been described in conditions with objective impairment (MCI). 36,37 As a multiplicity of factors influence the presence, type, and severity of cognitive complaints (age, comorbid pain, depression, fatigue, medication use, and medical disorders), their disappearance can be easily explained by the reversion of some of these clinical comorbidities. 37,38

Although SCCs have a clear place in research, care should be taken not to overemphasize them. Facing the heterogeneous and ambiguous meaning of SCC, they should be looked at as symptoms and we should avoid classifying them as a “condition.” The creation of a diagnostic category for SCC could lead to an increase in futile diagnostic examination and testing. Participants would be exposed to unnecessary stress for a symptom that ultimately will not lead to any disorder or early death. 36,39 Labeling an individual as affected by SCC should be minimized in order to avoid stigmatization. Nevertheless, if SCC as a group are associated with a higher risk of progression to cognitive impairment, it is reasonable to ask whether this risk varies among participants.

Our study tried to pinpoint the features of individuals with SCC associated with risk of progression. This risk probably represents a higher likelihood of harboring a neurodegenerative process. 40

The 3 yearlong follow-up performed by Jessen et al identified that the risk of progression of concerned complainers was 3.5 times higher than noncomplainers, while the risk of nonconcerned was nearly 2 times higher. 17 When this cohort was followed for 3 more years, 21 the 6-year risk of progression of concerned complainers decreased to 2.5, while nonconcerned complainers’ risk of progression was not significantly higher than noncomplainers’. This raises an interesting hypothesis that SMC is a risk factor for dementia in the short run (disclosing neurodegeneration) but loses significance over longer intervals. We can hypothesize that, if SMC participants don’t decline to MCI or AD at 3 years, their probability of worsening later is greatly reduced. This also introduces the idea that there could be different etiologies for SMC—a neurodegenerative one (associated with a 3-year risk of progression to dementia) and a nondegenerative one (that explains the reduced risk at 6 years), possibly related to anxiety or other psychiatric symptoms, common in SCC populations.

Interestingly, Jessen et al’s data also suggest that early MCI with memory concerns and SMI with concerns carry a similar risk of AD dementia (a 6-year risk of 2.44 for worried SMI and 2.46 for worried early MCI [data not shown in the tables]). 21 Therefore, the presence of SCC with concerns can have great value for identification of at-risk patients. 21,41 Authors suggested that biomarkers’ studies should expand their inclusion criteria, as cognitive testing is not sufficient for individual prediction of AD dementia. 21 Using only cognitive testing, studies will miss participants with pre-AD with a higher premorbid performance or with very effective compensatory mechanisms.

According to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, only 4 studies evaluated the significance of concern with the memory complaints. 17,21,29,31 All these publications were based on the AgeCoDe cohort. Further studies are necessary to understand the specific role of concerned complaints, as these have a higher risk of progression.

Sargent-Cox et al found that cognitive complainers aged 62 years who reported an impact of these subjective complaints in daily activities had a significantly higher risk of progression to MCI at 4 years. 22 The impairment in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) was identified by Luck et al 24 as a risk factor for incident MCI in 75-year-old cognitively normal persons, a characteristic that was recently associated with a higher risk of progression to dementia in MCI individuals. 42 The IADLs (eg, taking medication) are more cognitively demanding tasks than basic activities of daily living (eg, using the toilet) and are, therefore, more likely to be affected by early cognitive decline. 24,43 Impairment of IADL should be further studied to understand whether it represents a relevant marker of progression risk in participants with SCC.

We identified 2 studies showing that a report of declining cognition by a family element, in the absence of objective cognitive deficit, is associated with a 2 to 4 times higher risk of progression. 19,20 When the informant report was associated with self-reported SCC, Gifford et al found a significantly higher risk of progression. 19 This finding is consistent with previous studies. Following a convenience sample during 5 years, Carr et al showed that informant-reported memory complaints were a better predictor of the conversion of participants from Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) 0 to a non-CDR 0 status. 44 Informant-described complaints also seem to correlate better with objective cognitive impairment than self-reported cognitive complaints in persons ranging from normal cognition to mild dementia. 45 So there is an implicit acknowledgment that the individual’s own subjective evaluation of his or her cognitive functioning may not reflect an accurate appraisal of the actual cognitive deficit, at least in early and mid-dementia phases. 46 Probably informant complaints represent a decline from a previously higher cognitive level that is severe enough to be perceived by external observers.

Episodic memory loss is the earliest and most striking signature of AD. For reasons not completely understood, there is marked interpersonal variability in awareness of this deficit (metamemory). 47 Compromised awareness of cognitive impairment (anosognosia) has been observed in both MCI and early AD populations. 47,48 Also, areas associated with self-perception and awareness of deficits (ie, right prefrontal cortex 49,50 and right hippocampus 51 ) are often affected by early AD pathology. 52 So, it is not surprising that, if self-reported SCC represents an early metacognitive recognition of impairment, the increase in AD pathology during disease course could lead to a decrease in cognitive-monitoring functions and to disappearance of the self-complaints. External observers perceive the deficits’ progression without a metacognitive impairment, providing a marker of decline from previous states.

Only 1 of the included studies evaluated the role of educational levels on SCC progression. Chary et al 28 included 3777 elders aged 65 and older. He found that a complaint of difficulties in retaining new information was consistently associated with 3- and 10-year progression to dementia in participants with high-level education but not in low-level education. Participants with high-level education have a higher awareness of cognitive deficits/more reliable metacognitive processes than individuals with low-level education. 53 Maybe that is why their complaints associate with risk of progression as opposed to the lack of association in low-level education participants.

A common discussion in SCC evaluation is the role of affective disorders. Depression is common in older adults, and the association of depressive symptoms and cognitive complaints in the same patient is not rare in clinical practice. 54 Heser et al’s 29 combination of very late-onset depression (older than 70 years) with current depressive symptoms was probably a prodromal state of subsequent dementia rather than a risk factor. In their study, neither depression nor very late-onset depression was associated with dementia risk, but SMI and worried complainers had a significantly higher risk of dementia. When SMI with worries were studied as a variable, they fully mediated the association between depression parameters and dementia. Authors suggested that depression could be a consequence of worries about cognitive deterioration, and not an independent risk factor, and could therefore explain the higher levels of depression in individuals with SCC.

Definition of SCC

One relevant issue is the lack of a “gold standard” in the definition of SCC. The lack of a general definition of SCC and the existence of several terms (eg, SMC, SMI, SCC, and Subjective Cognitive Impairment [SCI]) constitutes a serious obstacle to the comparability of results across different studies. Distinct SCC scales are used, and different cognitive complaints could have dissimilar value in the risk of conversion to dementia. 28 All the studies included in this review, even if evaluating the same construct, presented different SCC assessment methods with different questions. The SCD-I tried to tackle this issue defining core criteria for SCI and recommendations for research. 9

We suggest that SCC should be assessed in 2 dimensions, the content of SCC (the cognitive tasks or functions that the patient feels that are diminished) and the severity of the complaints. Also, the perceived impact of these symptoms in daily activities should be measured. This model could be helpful for further SCC studies and in refinement of scales.

Suggestions for Further Research on SCC

Use of a standardized definition of SCC, making a clear distinction between the presence of complaints and the content of the complaints (specifically memory).

Use of a validated tool to assess SCC. This tool should be subjected not only to a proper translation but also to a cultural validation.

Use of both participants’ and proxy reports of SCC.

Evaluation of a wide range of factors in possible relation to SCC, namely, current and previous depressive symptoms.

Use of a prospective longitudinal design, with assessment in multiple time points of SCC, MCI, and dementia.

Assessment of objective cognitive performance with standard neuropsychological tools, using multiple endpoints.

Use of different clinical markers. Evaluation of early markers of a neurodegenerative process (for instance, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in Lewy bodies dementia) could add information in long-term evaluation studies.

Evaluation of baseline parameters (neuropsychological testing, clinical and demographic information, and noninvasive neuroanatomical and functional studies) that relate to SMC progression.

Conclusion

There is robust epidemiological evidence that SCC/SMI could represent, in a small group of subjects, a status with higher risk of progression to objective cognitive impairment. A higher risk of progression was identified in worried complainers, individuals who report impact of these complaints in daily activities, and those in whom the cognitive decline is corroborated by an informant. We suggest that these participants deserve a closer clinical and neuropsychological monitoring. Further studies are necessary to clarify the role of each factor in SCC progression risk and to define the importance of other parameters (such as educational level). Nevertheless, as the vast majority of participants with cognitive complaints do not progress to cognitive impairment, care must be taken to avoid unnecessary examinations and diagnostic procedures that would lead to significant stress to the individual.

Simultaneously, late-onset depression or depressive symptoms may not be independent risk factors for dementia but possible effects of SCC awareness. We suggest that very late-onset depression with current depressive symptoms also needs close monitoring, as this could as well represent a higher risk of cognitive impairment.

Footnotes

This article was accepted under the editorship of the former Editor-in-Chief, Carol F. Lippa.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Mitchell AJ, Beaumont H, Ferguson D, Yadegarfar M, Stubbs B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(6):439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holmen J, Langballe EM, Midthjell K, et al. Gender differences in subjective memory impairment in a general population: the HUNT study, Norway. BMC Psychol. 2013;1(1):19. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Ankri J, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints and mortality: does the type of complaint matter? J Psychiatr Res. 2014;48(1):73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchell AJ. Is it time to separate subjective cognitive complaints from the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment? Age Ageing. 2008;37(5):497–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Commissaris CJ, Verhey FR, Jr, Ponds RW, Jolles J, Kok GJ. Public education about normal forgetfulness and dementia: importance and effects. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;24(2):109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blackburn DJ, Wakefield S, Shanks MF, Harkness K, Reuber M, Venneri A. Memory difficulties are not always a sign of incipient dementia: a review of the possible causes of loss of memory efficiency. Br Med Bull. 2014;112(1):71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turvey CL, Schultz S, Arndt S, Wallace RB, Herzog R. Memory complaint in a community sample aged 70 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(11):1435–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abdulrab K, Heun R. Subjective Memory Impairment. A review of its definitions indicates the need for a comprehensive set of standardised and validated criteria. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):844–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Groot JC, de Leeuw FE, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Jolles J, Breteler MM. Cerebral white matter lesions and subjective cognitive dysfunction: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2001;56(11):1539–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jorm AF, Butterworth P, Anstey KJ, et al. Memory complaints in a community sample aged 60-64 years: associations with cognitive functioning, psychiatric symptoms, medical conditions, APOE genotype, hippocampus and amygdala volumes, and white-matter hyperintensities. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1495–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wehling E, Lundervold AJ, Standnes B, Gjerstad L, Reinvang I. APOE status and its association to learning and memory performance in middle aged and older Norwegians seeking assessment for memory deficits. Behav Brain Funct. 2007;3:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Harten AC, Visser PJ, Pijnenburg YA, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 is the best predictor of clinical progression in patients with subjective complaints. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramakers IH, Visser PJ, Bittermann AJ, et al. Characteristics of help-seeking behaviour in subjects with subjective memory complaints at a memory clinic: a case-control study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(2):190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmidtke K, Pohlmann S, Metternich B. The syndrome of functional memory disorder: definition, etiology, and natural course. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(12):981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steinberg SI, Negash S, Sammel MD, et al. Subjective memory complaints, cognitive performance, and psychological factors in healthy older adults. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(8):776–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jessen F, Wiese B, Bachmann C, et al. Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment: effects of severity and temporal association with cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Donovan NJ, Amariglio RE, Zoller AS, et al. Subjective cognitive concerns and neuropsychiatric predictors of progression to the early clinical stages of Alzheimer Disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(12):1642–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gifford KA, Liu D, Lu Z, et al. The source of cognitive complaints predicts diagnostic conversion differentially among nondemented older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3):319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caselli RJ, Chen K, Locke DE, et al. Subjective cognitive decline: self and informant comparisons. Alzheimer Dement. 2014;10(1):93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jessen F, Wolfsgruber S, Wiese B, et al. AD dementia risk in late MCI, in early MCI, and in subjective memory impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(1):76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sargent-Cox K, Cherbuin N, Sachdev P, Anstey KJ. Subjective health and memory predictors of mild cognitive disorders and cognitive decline in ageing: the Personality and Total Health (PATH) through Life Study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;31(1):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reisberg B, Shulman MB, Torossian C, Leng L, Zhu W. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(1):11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luck T, Luppa M, Briel S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: incidence and risk factors: results of the leipzig longitudinal study of the aged. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1903–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luck T, Riedel-Heller SG, Luppa M, et al. Risk factors for incident mild cognitive impairment--results from the German Study on Ageing, Cognition and Dementia in Primary Care Patients (AgeCoDe). Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(4):260–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yeung CM, St John PD, Menec V, Tyas SL. Is bilingualism associated with a lower risk of dementia in community-living older adults? cross-sectional and prospective analyses. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28(4):326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. St John P, Montgomery P. Does self-rated health predict dementia? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;26(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chary E, Amieva H, Pérès K, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Jacqmin-Gadda H. Short-versus long-term prediction of dementia among subjects with low and high educational levels. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):562–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heser K, Tebarth F, Wiese B, et al. Age of major depression onset, depressive symptoms, and risk for subsequent dementia: results of the German study on Ageing, Cognition, and Dementia in Primary Care Patients (AgeCoDe). Psychol Med. 2013;43(8):1597–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Waldorff FB, Siersma V, Vogel A, Waldemar G. Subjective memory complaints in general practice predicts future dementia: a 4-year follow-up study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(11):1180–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jessen F, Wiese B, Bickel H, et al. Prediction of dementia in primary care patients. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jungwirth S, Zehetmayer S, Bauer P, Weissgram S, Tragl KH, Fischer P. Prediction of Alzheimer dementia with short neuropsychological instruments. J Neural Transm. 2009;116(11):1513–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jungwirth S, Zehetmayer S, Weissgram S, Weber G, Tragl KH, Fischer P. Do subjective memory complaints predict senile Alzheimer dementia? Wien Med Wochenschr. 2008;158(3-4):71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Norden AG, Fick WF, de Laat KF, et al. Subjective cognitive failures and hippocampal volume in elderly with white matter lesions. Neurology. 2008;71(15):1152–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vellas B, Coley N, Ousset PJ, et al. Long-term use of standardised Ginkgo biloba extract for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (GuidAge): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(10):851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Canevelli M, Blasimme A, Vanacore N, Bruno G, Cesari M. Issues about the use of subjective cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease research. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):881–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glodzik-Sobanska L, Reisberg B, De Santi S, et al. Subjective memory complaints: presence, severity and future outcome in normal older subjects. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(3):177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vestberg S, Passant U, Elfgren C. Stability in the clinical characteristics of patients with memory complaints. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(3):e26–e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garcia-Ptacek S, Eriksdotter M, Jelic V, et al. Subjective cognitive impairment: towards early identification of Alzheimer disease [published online April 16]. Neurologia. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scheef L, Spottke A, Daerr M, et al. Glucose metabolism, gray matter structure, and memory decline in subjective memory impairment. Neurology. 2012;79(13):1332–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ouchi Y, Akanuma K, Meguro M, Kasai M, Ishii H, Meguro K. Impaired instrumental activities of daily living affect conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia: the Osaki-Tajiri Project. Psychogeriatrics. 2012;12(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pérès K, Chrysostome V, Fabrigoule C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Restriction in complex activities of daily living in MCI: impact on outcome. Neurology. 2006;67(3):461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carr DB, Gray S, Baty J, Morris JC. The value of informant versus individual’s complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology. 2000;55(11):1724–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Slavin MJ, Brodaty H, Kochan NA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of “subjective cognitive complaints” in the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(8):701–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roberts JL, Clare L, Woods RT. Subjective memory complaints and awareness of memory functioning in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28(2):95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cosentino S, Metcalfe J, Butterfield B, Stern Y. Objective metamemory testing captures awareness of deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. 2007;43(7):1004–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vogel A, Stokholm J, Gade A, Andersen BB, Hejl AM, Waldemar G. Awareness of deficits in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: do MCI patients have impaired insight? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(3):181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sedaghat F, Dedousi E, Baloyannis I, et al. Brain SPECT findings of anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(2):641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vogel A, Hasselbalch SG, Gade A, Ziebell M, Waldemar G. Cognitive and functional neuroimaging correlate for anosognosia in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marshall GA, Kaufer DI, Lopez OL, Rao GR, Hamilton RL, DeKosky ST. Right prosubiculum amyloid plaque density correlates with anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(10):1396–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aalten P, van Valen E, de Vugt ME, Lousberg R, Jolles J, Verhey FR. Awareness and behavioral problems in dementia patients: a prospective study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(1):3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Balash Y, Mordechovich M, Shabtai H, Giladi N, Gurevich T, Korczyn AD. Subjective memory complaints in elders: depression, anxiety, or cognitive decline? Acta Neurol Scand. 2013;127(5):344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]