Abstract

Urinary tract infection is the most frequently diagnosed kidney and urologic disease and Escherichia coli is by far the most common etiologic agent. Uropathogenic strains have been shown to contain blocks of DNA termed pathogenicity islands (PAIs) which contribute to their virulence. We have defined one of these regions of DNA within the chromosome of a highly virulent E. coli strain, CFT073, isolated from the blood and urine of a woman with acute pyelonephritis. The 57,988-bp stretch of DNA has characteristics which define PAIs, including a size greater than 30 kb, the presence of insertion sequences, distinct segmentation of K-12 and J96 origin, GC content (42.9%) different from that of total genomic DNA (50.8%), and the presence of virulence genes (hly and pap). Within this region, we have identified 44 open reading frames; of these 44, 10 are homologous to entries in the complete K-12 genome sequence, 4 are nearly identical to the sequences of E. coli J96 encoding the HlyA hemolysin, 11 encode P fimbriae, and 19 show no homology to J96 or K-12 entries. To determine whether sequences found within the junctions of the PAI of CFT073 were common to other uropathogenic strains of E. coli, 11 probes were isolated along the length of the PAI and were hybridized to dot blots of genomic DNA isolated from clinical isolates (67 from patients with acute pyelonephritis, 38 from patients with cystitis, 49 from patients with catheter-associated bacteriuria, and 27 from fecal samples). These sequences were found significantly more often in strains associated with the clinical syndromes of acute pyelonephritis (79%) and cystitis (82%) than in those associated with catheter-associated bacteriuria (58%) and in fecal strains (22%) (P < 0.001). From these regions, we have identified a putative iron transport system and genes other than hly and pap that may contribute to the virulent phenotype of uropathogenic E. coli strains.

Escherichia coli is by far the most common cause of urinary tract infection (UTI), particularly in uncomplicated cases. Strains causing these infections possess traits that distinguish them from commensal strains of E. coli and other pathogenic strains such as those causing diarrhea and meningitis. Characteristically, uropathogenic strains of E. coli are composed of a restricted number of O serogroups, produce hemolysin, P fimbriae, and aerobactin, exhibit serum resistance, and are encapsulated (6, 7, 14, 15, 18, 31, 35). The presence of these features, not found in the typical fecal strain, implies that uropathogenic strains possess a defined set of virulence determinants that allow the bacterium to colonize the urinary tract, avoid host defenses, and elicit histological damage to the uroepithelium, allowing in some cases passage of the bacterium into the bloodstream.

Indeed, such clustered sets of virulence genes, termed pathogenicity islands (PAIs), have been defined for three strains of uropathogenic E. coli: 536 (3), J96 (39), and CFT073 (17). Typically, these sequences are large (>30-kb) blocks of DNA inserted within or near tRNA genes (12, 33, 39), contain direct repeats and insertion sequences, have a GC content that differs from that of the rest of the genome, and encode defined virulence determinants (3, 19, 26). We have previously shown that such sequences are widespread among uropathogenic isolates (17). One probe from the PAI of strain CFT073 hybridized with genomic DNA from approximately 80% of acute pyelonephritis and cystitis strains but only 19% of fecal strains.

Previously in our laboratory the boundaries of a PAI were identified for E. coli CFT073, a highly virulent strain isolated from the blood and urine of a woman with acute pyelonephritis (17). In this report, we provide an analysis of the nucleotide sequence for a 57,988-bp region. Previously unrecognized open reading frames (ORFs), as well as homologs of characterized genes of other species, were found. In addition, we identified the distribution of these sequences that span the PAI among the majority of other uropathogenic strains of E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

E. coli CFT073 was isolated from the blood and urine of a woman admitted to the University of Maryland Medical System for the treatment of acute pyelonephritis (27). This hly+ pap+ sfa+ pil+ strain is highly virulent in the CBA mouse model of ascending UTI (28) and is cytotoxic for cultured human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (27). It is phenotypically positive for the production of P fimbriae, hemolysin, and type 1 fimbriae. E. coli DH5α (34) was used as a recipient for gene bank and recombinant clones.

Four collections of E. coli strains were established from humans with appropriate clinical syndromes. The first consists of 67 isolates from the urine or blood of patients (43 women and 24 men) who were admitted to the University of Maryland Medical System with acute pyelonephritis (bacteriuria of ≥105 CFU/ml, pyuria, fever, and no other source of infection) (27). The second collection consists of 38 isolates from the urine of women with cystitis. These isolates were kindly provided by A. Stapleton (University of Washington) and B. Foxman (University of Michigan) (10). The third collection consists of 49 isolates from the urine of 26 patients with long-term urinary catheters in place (41). Each was isolated during the first week of a new epidemiologically defined episode of E. coli bacteriuria. The fourth collection consists of 27 control strains of E. coli from the feces of healthy women (20 to 50 years old) who had not had a symptomatic UTI or known bacteriuria within the previous 6 months and who had not experienced diarrhea or received antibiotics within the preceding 1 month (28).

Cosmid library.

A cosmid library was constructed with partially Sau3A-digested genomic DNA isolated from E. coli CFT073. DNA was ligated into BamHI-digested pHC79. The ligation mixture was packaged in vitro with the Gigapack lambda packaging kit (Stratagene) and used to infect E. coli DH5α. Transformants were selected on Luria agar containing ampicillin (200 μg/ml).

Preparation of templates for nucleotide sequencing.

Three overlapping cosmid clones (8-3f, 18-2f, and 5-4a), prepared from genomic DNA from E. coli CFT073 (28) and found previously to carry a PAI (17), were used to prepare subclones for nucleotide sequencing by deletion, subcloning of specific restriction fragments, and PCR amplification of specific sequences.

Nucleotide sequencing and analysis.

Double-stranded DNA was used as a template for sequencing by the dideoxy-chain termination method (36). Primers used in these studies are listed in Table 1. Reactions were run with reagents from a Prism Ready Reaction Dye Deoxy Termination kit (Applied Biosystems) in conjunction with Taq polymerase. A model 373A DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) was used, and sequences were determined in both directions. DNAsis software (version 2.1; Hitachi) was used for analysis of the DNA sequence for base composition, identification of ORFs and restriction sites, and other basic analyses. Apparent homologies between ORFs both outside and inside the PAI were sought in GenBank by using the Wisconsin Package (version 8.1; Genetics Computer Group, Inc.).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for nucleotide sequence determination

| Primer | Orientation | Coordinate (5′ end) | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 637 | TGTCGGCGTTCGTTGTC |

| 2 | F | 1997 | TGGGCAGCAGATCGCTTGGG |

| 3 | R | 2099 | CTGGTGCTGGGGCTATT |

| 4 | F | 2740 | GCCAGCGCCAGGTTACTT |

| 5 | R | 3630 | GCCATTCAGTGCGGTCTT |

| 6 | R | 4350 | CCAGCCCATACGACGATA |

| 7 | F | 4922 | GGCAGGCTTTGCTGTTTC |

| 8 | R | 5305 | TGGAATGGCGGGCAGC |

| 9 | F | 5891 | CCGCTATCCGCTTTCACA |

| 10 | F | 6314 | CGTGCCGCTGTTCTGATT |

| 11 | F | 7309 | GCTGGCTACCGCTGACTT |

| 12 | F | 7818 | ACGGACTGCTGGGTAAAG |

| 13 | F | 7863 | CGTTTTTTGAGTCTCATAGA |

| 14 | R | 7926 | GCAACCCGCAGCCTCTAT |

| 15 | R | 8732 | GCGTTACTTCTGGAAGATAT |

| 16 | F | 8965 | TAAAATCAACGTGAGCATAA |

| 17 | R | 9182 | GGCTTCCCGCTCCACTCT |

| 18 | R | 9324 | CGATTTATGGCGTTGATT |

| 19 | R | 9553 | GATTTTGCAGACCTTTACCT |

| 20 | F | 9716 | GCTGTCGGCAATGGCGTT |

| 21 | R | 10224 | GGTTGGGGCAAAACCACAATTATG |

| 22 | F | 19470 | TGTTTCCCGTTGATACTA |

| 23 | R | 20703 | GCTTGTGGGCTCGTCCTC |

| 24 | F | 28625 | TCATATCTTCTCCTGTCA |

| 25 | F | 29644 | GCCGCTCATCACTTTGTT |

| 26 | F | 30351 | GCTGCTATTACCTTCTTC |

| 27 | F | 43124 | AAATCAGCCACCCACAGC |

| 28 | R | 44277 | TTGTGCGTGTTTTCTTCA |

| 29 | R | 44841 | CGTAATGACTGGGAGAGA |

| 30 | F | 45318 | GGCGAACTCATCCACATT |

| 31 | F | 45971 | GACGTTGTTGGTTTGATG |

| 32 | F | 46775 | CGGGAGAATGAAATGAAAA |

| 33 | F | 47414 | GAAACAACCGACGAAATA |

| 34 | R | 48820 | TTGTAAATCCTCAGAAGA |

| 35 | R | 49564 | CCGCCGTTGCATTGTTCT |

| 36 | R | 50019 | ATACGCCTTTTCAGATGT |

| 37 | R | 50677 | CAACGCCTTTTCCTTAT |

| 38 | F | 50866 | TATCTTCTGACGCTATGC |

| 39 | F | 51441 | CGAACTGAAAGGTGAAAG |

| 40 | F | 52199 | TTTCGCTAGGTATCACA |

| 41 | F | 52944 | TGGTCACACCGCCTTTCA |

| 42 | F | 53624 | CCCTGACGCTGTTGTGTG |

| 43 | F | 54164 | GCCGAGACAATCATCACA |

| 44 | R | 55298 | CGTAAGGCCAGCTGATGGTG |

| 45 | R | 55755 | TTTCGCGTTTCTACCACAA |

| 46 | F | 56090 | TGGTGATAGCGTCTGGTA |

| 47 | F | 56622 | GCCACTTCGACACACACC |

| 48 | F | 57074 | TGGCGTAAAGCGGAAAAC |

| 49 | R | 58040 | TCAAGTCGCGTGTTATGC |

| 50 | R | 58552 | CTGAGCATCCGGCTAACC |

| 51 | R | 58736 | TCAGGCAAGGCAATGTTTG |

| 52 | R | 59005 | CCAGCAGGAAGTTGCGGA |

DNA probes and dot blot hybridization.

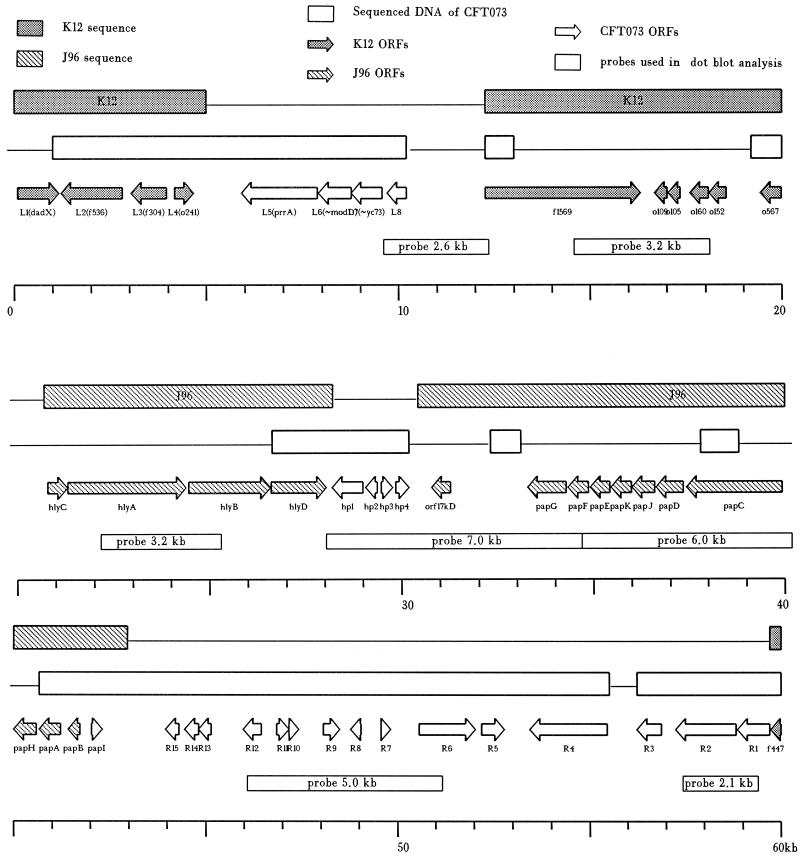

DNA restriction fragments isolated from cosmid clones 8-3f and 5-4a and subclones 8HS9 and 5HS11B were used as gene probes to determine whether homologous sequences were present in genomic DNA preparations of E. coli strains isolated from clinical sources. E. coli CFT073 and DH5α were used as positive and negative controls. Fragments were labeled by using the Amersham enhanced chemiluminescence system. For dot blots, E. coli strains were cultured in Luria broth (80 μl) in 96-well microtiter plates. Bacterial suspensions were lysed and pipetted onto a nucleic acid transfer membrane. Samples were neutralized with Southern blot neutralization buffer (34). Hybridization was done with 11 probes encompassing the length of the PAI (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Features of the pathogenicity island of E. coli CFT073. ORFs defined by nucleotide sequencing are shown as arrows. The ORF designations, below the arrows, are defined in Table 2. The direction of each arrow indicates the predicted direction of transcription. The top line of shaded boxes indicates that ORFs in this region are highly homologous to or identical with ORFs previously identified in E. coli K-12 (dark shading) (2) or uropathogenic J96 (light shading) (1, 8, 20, 21, 29, 30, 32, 40). The unshaded boxes on the second line indicate regions in which the complete nucleotide sequence was obtained in both directions. Sample sequencing was conducted only in areas not covered by unshaded boxes; these regions matched K-12 or J96 sequences with respect to restriction endonuclease sites or nucleotide sequence identity. The positions of restriction fragments or PCR products that were used as probes for DNA hybridization are shown below the ORFs. The scale at the bottom is shown in kilobases. Cosmid clone 8-3f includes ∼35 kb of the PAI beginning 3 kb to the left of the depicted left junction (0 kb) and extending to the center of the pap operon (∼39 kb). Subclone 8HS9 includes PAI sequences from ∼10 to 17 kb. Cosmid clone 5-4a includes ∼37 kb extending from the center of the hemolysin gene cluster (∼23.5 kb) to 5 kb to the right of the right junction (58 kb). Subclone 5H11B extends from ∼38 to 49 kb.

Probes including the prrA, modD, yc73, and L8 genes were PCR amplified from cosmid clone 8-3f (17), by using primer pairs 9-14, 13-15, 16-19, and 20-21, respectively. SalI-digested 8-3f and BamHI/SmaI-digested 8HS9 (a SalI/HindIII-digested 8-3f subclone) resulted in probes of sizes 2.6 and 3.2 kb. HindIII digestion of cosmid 8-3f allowed the isolation of a 3.2-kb fragment from within the hemolysin gene cluster. A HindIII digest of cosmid clone 5-4a (17) included fragment sizes of 7.0 and 6.0 kb. The 5.0-kb probe was obtained from a SmaI digest of 5H11B (a HindIII/BamHI-digested 5-4a subclone). Finally, the 2.1-kb probe was isolated by PCR amplification of cosmid 5-4a, by using primers 38 and 42 (Table 1). Autoradiographs were developed as described by Kafatos et al. (16). Southern blots were prepared by standard methods (34) and developed with the Amersham enhanced chemiluminescence system as specified by the manufacturer.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the ORFs within the boundaries of the left and right junctions of the PAI of E. coli CFT073 have been assigned GenBank accession no. AF081283, AF081284, AF081285, and AF081286.

RESULTS

Novel genes inside the PAI.

To determine whether newly described genes were present within the boundaries of the PAI, a 61-kb region was subjected to nucleotide sequencing. In this region, which included an apparent 58-kb PAI, we have identified 44 ORFs (Fig. 1). These are listed along with homologs and their accession numbers in Table 2. Four small gaps (∼2, ∼1, ∼1, and <1 kb) that presented difficulties in sequencing, PCR amplification, and subcloning are also identified (Fig. 1). Among the sequenced ORFs are genes that appear to be involved in iron utilization and transcriptional regulation (see below).

TABLE 2.

ORFs identified by nucleotide sequencing of a PAI of E. coli CFT073

| ORFa | Coordinatesb | Homolog | Description of product encodedc | Probabilityd | Accession no. of homolog |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 85–1155 | dadX | Alanine racemase | 1.3e−254 | P29012 |

| L2 | 2822–1212 C | f536 | 536-aa ORF product of E. coli | 0.0 | AE000217 |

| L3 | 3957–3043 C | f304 | 304-aa ORF product of E. coli | 3.3e−216 | AE000217 |

| L4 | 4165–4668 | o241 | 241-aa ORF product of E. coli | 4.8e−113 | AE000217 |

| L5 | 7879–5909 C | prrA | TonB-dependent outer membrane receptor | 0.0 | U85771 |

| L6 | 8762–7905 C | modD | Molybdenum transport protein | 1.2e−200 | U85771 |

| L7 | 9571–8759 C | orf2 | Similar to H. influenzae yc73 protein | 1.6e−112 | U85771 |

| L8 | 10203–9705 C | fepC | Ferric enterobactin transport ATP-binding protein | 1.5e−31 | F64113 |

| Gap GL (∼2 kb) | |||||

| f1569 | 12502–16056 | 1,569-aa ORF product of E. coli | ECAE000350 | ||

| o109 | 16749–16420 C | 109-aa ORF product of E. coli | ECAE000349 | ||

| o105 | 17087–16770 C | 105-aa ORF product of E. coli | ECAE000349 | ||

| o160 | 17816–17334 C | 160-aa ORF product of E. coli | ECAE000349 | ||

| o152 | 18283–17825 C | 152-aa ORF product of E. coli | ECAE000349 | ||

| o567 | 20882–19181 C | 567-aa ORF product of E. coli | ECAE000349 | ||

| Gap LH (∼1 kb) | |||||

| hlyC | 21357–21869 | Chromosomal hemolysin C | M10133 | ||

| hlyA | 21881–24952 | Chromosomal hemolysin A | M10133 | ||

| hlyB | 25023–27146 | Chromosomal hemolysin B | M10133 | ||

| hlyD | 27165–28601 | Chromosomal hemolysin D | 2.7e−285 | Y13891 | |

| HP1 | 29731–28913 C | IS600 hypothetical 31-kDa protein | 7.0e−195 | P16940 | |

| HP2 | 30069–29767 C | IS600 hypothetical 11-kDa protein | 2.1e−60 | P16939 | |

| HP3 | 30172–30462 | Unknown protein of plasmid Ti | 2.1e−07 | M25805 | |

| HP4 | 30547–30894 | Hypothetical 15.6-kDa protein | 7.7e−42 | P50359 | |

| Gap HP (∼1 kb) | |||||

| papG | 34008–33001 C | P-pilus F13 tip protein | X61239 | ||

| papF | 34555–34052 C | P-pilus F13 tip protein | X61239 | ||

| papE | 35151–34630 C | P-pilus F13 tip protein | X61239 | ||

| papK | 35709–35176 C | P-pilus F13 tip protein | X61239 | ||

| papJ | 36300–35719 C | P-pilus F13 | X61239 | ||

| papD | 37053–36337 C | P-pilus F13 | X61239 | ||

| papC | 39649–37139 C | P-pilus F13 | X61239 | ||

| papH | 40295–39708 C | P-pilus F13 | X61239 | ||

| papA | 40925–40359 C | P-pilus F13 | X61239 | ||

| papB | 41446–41132 C | P-pilus F13 | X61239 | ||

| papI | P-pilus F13 | X61239 | |||

| R15 | 43029–42643 C | Putative transposase of E. coli | 1.6e−73 | U06468 | |

| R14 | 43529–43174 C | Transposase (IS629) | 8.6e−74 | P16942 | |

| R13 | 43855–43529 C | 12.7-kDa protein of E. coli | 3.1e−51 | U06468 | |

| R12 | 45171–44695 C | Transposase (ISAE1) | 3.4e−06 | A47041 | |

| R11 | 45575–45887 | Possible precursor polypeptide | 0.88 | X00729 | |

| R10 | 45884–46144 | Hypothetical 8.6-kDa protein in dinG/rarB 3′ region | 6.2e−06 | P41038 | |

| R9 | 46789–47217 | f200 | 200-aa ORF product of E. coli | 3.0e−08 | AE000137 |

| R8 | 47771–47503 C | Neurotensin receptor | 0.32 | P30989 | |

| R7 | 48288–48534 | Maltopentaose-forming amylase | 0.038 | D10769 | |

| R6 | 49286–50752 | Transposase of Chelatobacter heintzii | 3.7e−06 | L49438 | |

| R5 | 50914–51501 | orfB | Hypothetical protein B of Bacillus | 1.1e−46 | S23889 |

| R4 | 54177–52168 C | Exogenous ferric siderophore receptor | 2.2e−162 | U56084 | |

| Gap GR (<1 kb) | |||||

| R3 | 56231–55869 C | β-Cystathionase | 7.1e−100 | U65013 | |

| R2 | 57811–56231 C | malX | Phosphotransferase system maltose- and glucosespecific IIabc component | 3.5e−155 | P19642 |

| R1 | 58724–57843 C | sacpa operon antiterminator | 2.6e−53 | P26212 | |

| f447 | 60267–58885 C |

For positions of ORFs, see Fig. 1.

Base pair number beginning at left junction of PAI; C indicates that ORF is found on the complementary strand.

Description of the best homolog. aa, amino acid.

Probability value (P) of <0.05 is considered significant.

Notable homologs.

Four ORFs inside the left junction (defined as the sequences associated with lower numbers on the E. coli K-12 linkage map), prrA, modD, yc73, and fepC, represent an apparent iron transport system. The genes are contiguous and are predicted to be transcribed in the same direction; however, this has not been demonstrated experimentally. In other systems (25), the modD gene is part of a gene cluster involved in molybdenum transport, although no specific function has been ascribed to this gene. Another iron acquisition gene homolog, comprising the R4 ORF (terminology used in Fig. 1 and Table 2), appears to encode a homolog of an exogenous ferric siderophore receptor (9).

Just inside the right junction of the PAI (defined as the sequences associated with higher numbers on the E. coli K-12 linkage map) is an apparent antiterminator with homology to a gene in the sac operon of Bacillus subtilis (11) (Fig. 1; Table 2). Based on studies with homologs (37, 38), this gene may act on the next gene, R2, which encodes a homolog of the maltose- and glucose-specific component IIa of a phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system. The adjacent gene R3 encodes a homolog of β-cystathionase (cystathionine-β lyase), the gene product of metC, which converts cystathione to homocysteine (4).

Insertion sequences and transposons.

Six ORFs, designated HP1, HP2, R15, R14, R12, and R6, are related to insertion sequences and transposons which are common features of PAIs (26). The HP1 and HP2 ORFs represent the IS600 hypothetical 31- and 11-kDa proteins (24), respectively. R14 represents the transposase from insertion sequence IS629 (22). These two insertion sequences, which are members of the IS3 family and are found elsewhere in the K-12 genome (5), were originally identified in a strain of Shigella sonnei, a species closely related to E. coli (23).

Other features of the PAI.

The PAI of strain CFT073 displays two other features common to such blocks of virulence genes. First, the GC content of the sequences, not including those of K-12 origin, is 42.9%. This value is significantly different from a value of 50.8% for the E. coli genome (2). Also, there appears to be segmentation with respect to unique PAI sequences and sequences of K-12 origin. Approximately 7 kb downstream of the left junction of the PAI, there is an 8-kb sequence, identical to that found in the K-12 genome, carrying six ORFs (Fig. 1). The hemolysin gene cluster hlyCABD follows this block.

PAI sequences are associated with virulent strains.

To determine whether sequences found within the junctions of the PAI are common to other uropathogenic strains of E. coli, 11 probes were isolated along the length of the PAI (Fig. 1) and used to hybridize dot blots of genomic DNA isolated from clinical isolates (Table 3). A high percentage of isolates from patients with acute pyelonephritis or cystitis reacted with the probes (mean = 81%). These proportions were significantly higher than for strains from patients with catheter-associated bacteriuria (mean = 58%) or from fecal strains (mean = 22%) (P < 0.001) indicating that genomic sequences homologous to those of PAI sequences from strain CFT073 are found in most other strains recovered from patients with cystitis or pyelonephritis.

TABLE 3.

Strains isolated from clinical sources that hybridized with DNA probes isolated from the PAI of strain CFT073

| Strain

|

% of isolates positive by dot blot hybridization with given probea

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | No. | prrA | modD | yc73 | fepC | 2.6 | 3.2 | 3.2 (hly) | 7.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 2.1 |

| Patient with pyelonephritis | 67 | 87 | 93 | 90 | 87 | 84 | 75 | 49 | 79 | 81 | 64 | 79 |

| Patient with cystitis | 38 | 87 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 87 | 79 | 79 | 76 | 84 | 63 | 81 |

| Patient with catheter-associated bacteriuria | 49 | 67 | 69 | 61 | 61 | 63 | 65 | 41 | 57 | 61 | 41 | 48 |

| Fecal sample | 27 | 26 | 33 | 19 | 22 | 22 | 37 | 11 | 15 | 22 | 11 | 19 |

Positions of probes are shown in Fig. 1.

Hybridization signatures of clinical isolates.

Since uropathogenic strains clearly carry sequences that are homologous to sequences in the first CFT073 PAI, we examined which probes reacted with each isolate in the strain collection. Each strain was assigned a signature based on a positive or negative hybridization with 11 probes (Table 4). Of the 35 strains that reacted with all 11 probes, 18 were pyelonephritis-associated strains and 17 were cystitis-associated strains; no fecal strains fell into this category (P < 0.007). The 72 strains that reacted with either 10 or all 11 probes included 39 of 67 (58%) pyelonephritis-associated strains, 23 of 38 (61%) cystitis-associated strains, 10 of 49 (20%) strains from patients with catheter-associated bacteriuria, but only 1 of 27 (4%) fecal strains (P < 0.0001). Of the 12 strains that reacted with none of the probes, 11 were fecal strains and 1 was from a patient with catheter-associated bacteriuria. The 20 strains that reacted with either none or only 1 probe included only 1 of 67 (1%) pyelonephritis-associated strains, none of the cystitis-associated strains, 3 of 49 (6%) strains from patients with catheter-associated bacteriuria, but 16 of 27 (59%) fecal strains (P < 0.0001). These results indicate that PAI sequences present in E. coli CFT073 are also found in other uropathogenic strains, especially those isolated from patients suffering with pyelonephritis and cystitis. These sequences are not generally found in fecal strains and are found less frequently in isolates from patients with catheter-associated bacteriuria.

TABLE 4.

Hybridization signatures for clinical strains

| Signaturea | No. of positive probes | No. of isolates from:

|

Total no. of strains | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with pyelonephritis | Patients with cystitis | Patients with catheterrelated bacteriuria | Fecal sample | |||

| 11111111111 | 11 | 18 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 36 |

| 11111101111 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 16 |

| 11111011111 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 9 | |

| 11111111101 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 8 | |

| 11111111110 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 11111101110 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| 11111001111 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| 11111101101 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| 11111100001 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 11111000001 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| 11111100000 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 10000111110 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| 11111000000 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 00000101100 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 00000001100 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 00000100000 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| 00000000000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 12 |

Signatures (denoting positive [1] or negative [0] hybridization with 11 probes) represented by only one or two strains are as follows: for patients with pyelonephritis, 11111111100, 11111001101, 11110011110, 01111011001, 01111000111, 11110101100, 01110001111, 01001101101, 11101000101, 11110001100, 00000111110, 10000100011, 01010000001, 10000000011, 01110000000, 00000100001; for patients with cystitis, 11111010111, 11111011101, 11111111001, 11111100101, 01111011101, 11111010001, 11111010000, 11111000100, 00000111111, 01110000001, 00000000101, 00000000001; for patients with cathe- ter-associated bacteriuria, 11111100111, 01011011111, 11111101100, 11111101001, 1111100101, 11111101000, 11110001110, 01111100001, 11011010100, 10000101110, 01101000011, 11110000001, 01000101100, 10010000000, 10000000100, 01000100000, 00000010000, 10000000000; fecal samples, 11111100111, 01111101111, 10000101110, 11110100000, 11001000001, 01000010100, 01000010000, 00000001000.

DISCUSSION

We have characterized a 61-kb region of DNA from E. coli CFT073, a pyelonephritis- and bacteremia-associated isolate, by isolation of overlapping cosmid clones, restriction endonuclease mapping, subcloning, hybridization, and nucleotide sequencing (Fig. 1). In this region, we have identified what can be defined as a PAI that includes 44 ORFs (Table 2). PAIs are typically larger than 30 kb (3), have a GC content lower than that of neighboring DNA (19), and have gene clusters positioned near each other which contribute to a single virulence property (26). The first PAI of CFT073 is 58 kb in size (Fig. 1), has a GC content of 42.9% (compared to 50.8% in K-12 genomic DNA), and includes the genes encoding HlyA hemolysin and P fimbriae.

Distinct segmentation and insertion sequences are also common features of PAIs, which suggests that DNA rearrangements mediated by illegitimate or recA-dependent recombination have occurred or that DNA has been inserted by transposons, phage, or integrons (19, 26). This 61-kb region shows some evidence of rearrangement with the K-12 genome, as two blocks of four and six ORFs within this region closely match entries in the complete K-12 genome sequence (Fig. 1, darkly shaded boxes). Another four genes, in the hylCABD cluster, encode the HlyA hemolysin and are nearly identical to sequences from E. coli J96, a notable uropathogenic strain. Also carried on this stretch of DNA is the pap operon, comprising of 11 ORFs (papIBAHCDJKEFG) encoding one of the two P fimbriae expressed by this strain (28); this pap operon encodes a class II PapG adhesin (data not shown). Insertion elements and transposases occur six times in the region, perhaps predisposing these sequences to rearrangement. Remaining are 19 ORFs, which are also listed in Table 2, beginning at the left junction of the PAI and moving toward the right junction.

Nucleotide sequences of the first 58-kb PAI of CFT073 reveal newly described genes. These gene sequences, as assayed by DNA hybridization, are present in virulent uropathogenic strains and are generally absent in nonvirulent strains. Therefore, we postulate that these newly described genes may represent virulence determinants that contribute to the pathogenesis of cystitis and acute pyelonephritis caused by uropathogenic E. coli. As we continue our studies on the pathogenicity islands of CFT073, we will select mutants with phenotypes that may relate to virulence such as iron uptake, metabolite uptake, and transcriptional regulation. We will undertake allelic exchange mutagenesis of specific genes and test these mutants by in vitro assays and, in vivo, by using the CBA mouse model of ascending UTI (13). By creating such mutants, we hope to determine which genes contribute to the virulence phenotype of uropathogenic E. coli.

It is likely, however, that strain CFT073 contains another PAI. For two other uropathogenic strains that have been studied closely, 536 and J96, each strain was found to contain two separate PAIs. For strain 536, PAIs of 190 and 70 kb are inserted at 97 min (within leuX) and 82 min (within selC), respectively (reviewed in reference 19). For strain J96, PAIs of 110 and >170 kb are inserted at 94 min (within pheR) and 64 min (within pheV), respectively (39). Because we know that strain CFT073 contains two complete pap operons encoding distinct P fimbriae (28) and that only one operon is found in the PAI described in this report (17), it is likely that these sequences are found in a separate PAI along with the genes encoding F1C fimbriae (foc [unpublished observation]). That CFT073 has another PAI of unknown size raises the possibility that a significant number of virulence genes, not detected on the PAI described here, also contribute to the virulence of this strain.

Finally, an important question raised by these studies is whether there are distinctions between strains isolated from patients with cystitis and strains from patients with pyelonephritis. Based on hybridization of chromosomal DNA with PAI probes, we are unable to make such a distinction. With the exception of the hly hemolysin-containing probe, there were no significant differences (P > 0.2) between the percentages of cystitis and pyelonephritis isolates that reacted with each of the 11 PAI probes (Table 3). In contrast, other hybridization studies which used specific probes (e.g., pap, hly, sfa, and foc) have revealed that a higher percentage of pyelonephritis-associated isolates than of cystitis-associated isolates reacted with these probes (6). It is now clear that uropathogenic isolates generally express adhesins that aid in colonization and toxicity (hemolysin and cytotoxic necrotizing factor), but this group of strains clearly does not have a single phenotype (6). It will be interesting to see whether cystitis and pyelonephritis strains are, in the future, delineated on the basis of specific genotypes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant DK47920 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baga M, Normark S, Hardy J, O’Hanley P, Lark D, Olsson O, Schoolnik G, Falkow S. Nucleotide sequence of the papA gene encoding the Pap pilus subunit of human uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:330–333. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.1.330-333.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum G, Falbo V, Caprioli A, Hacker J. Gene clusters encoding the cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1, Prs-fimbriae, and α-hemolysin form of the pathogenicity island II of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain J96. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;126:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown E A, D’Ari R, Newman E. A relationship between l-serine degradation and methionine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1017–1023. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-6-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deonier R C. Native insertion sequence elements: locations, distributions, and sequence relationships. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2220–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnenberg M S, Welch R A. Virulence determinants of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. In: Mobley H L T, Warren J W, editors. Urinary tract infections: molecular pathogenesis and clinical management. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 135–174. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowling K J, Roberts J A, Kaack M B. P-fimbriated Escherichia coli urinary tract infection: a clinical correlation. South Med J. 1987;80:1533–1536. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198712000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felmlee T, Pellett S, Welch R A. Nucleotide sequence of an Escherichia coli chromosomal hemolysin. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:94–105. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.94-105.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiss E H, Yu S, Jacobs W R., Jr Identification of genes involved in the sequestration of iron in mycobacteria: the ferric exochelin biosynthetic and uptake pathways. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14(3):557–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foxman B, Zhang L, Palin K, Tallman P, Marrs C F. Bacterial virulence characteristics of Escherichia coli isolate from first-time urinary tract infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1514–1521. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser P, Kunst F, Arnaud M, Coudart M P, Gonzales W, Hullo M F, Ionescu M, Lubochinsky B, Marcelino L, Moszer I, Presecan E, Santana M, Schneider E, Schweizer J, Vertes A, Rapoport G, Danchin A. Bacillus subtilis genome project: cloning and sequencing of the 97-kb region from 325 degrees of 333 degrees. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:371–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hacker J. Genetic determinants coding for fimbriae and adhesins of extraintestinal Escherichia coli. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;151:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74703-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagberg L, Engberg I, Freter R, Lam J, Olling S, Svanborg-Eden C. Ascending unobstructed urinary tract infection in mice cause by pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli of human origin. Infect Immun. 1983;40:273–283. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.273-283.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson J R. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:80–128. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson J R, Moseley S L, Roberts P L, Stamm W E. Aerobactin and other virulence factor genes among strains of Escherichia coli causing urosepsis: association with patient characteristics. Infect Immun. 1988;56:405–412. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.405-412.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kafatos F C, Jones C W, Efstratiadis A. Determination of nucleic acid sequence homologies and relative concentrations by a dot blot hybridization procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1541–1552. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao J-S, Stucker D M, Warren J W, Mobley H L T. Pathogenicity island sequences of pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli CFT073 are associated with virulent uropathogenic strains. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2812–2820. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2812-2820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latham R H, Stamm W E. Role of fimbriated Escherichia coli in urinary tract infections in adult women: correlation with localization studies. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:835–840. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee C A. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of bacterial pathogens. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindberg F, Lund B, Johansson L, Normark S. Localization of the receptor-binding protein adhesin at the tip of the bacterial pilus. Nature (London) 1987;328:84–87. doi: 10.1038/328084a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lund B, Lindberg F, Marklund B-I, Normark S. The PapG protein is the α-d-galactopyranosyl-(1-4)-β-d-galactopyranose-binding adhesin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5898–5902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsutani S, Ohtsubo E. Complete sequence of IS629. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1899. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsutani S, Ohtsubo E. Distribution of the Shigella sonnei insertion elements in Enterobacteriaceae. Gene. 1993;127:111–115. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90624-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsutani S, Ohtsubo H, Maeda Y, Ohtsubo E. Isolation and characterization of IS elements repeated in the bacterial chromosome. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:445–455. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maupin-Furlow J A, Rosentel J K, Lee J H, Deppenmeier U, Gunsalus R P, Shanmugam K T. Genetic analysis of the modABCD (molybdate transport) operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4851–4856. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4851-4856.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mecsas J, Strauss E J. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence: type III secretion and pathogenicity islands. Synopses. 1996;2(4):271–288. doi: 10.3201/eid0204.960403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mobley H L T, Green D M, Trifillis A L, Johnson D E, Chippendale G R, Lockatell C V, Jones B D, Warren J W. Pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli and killing of cultured human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells: role of hemolysin in some strains. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1281–1289. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1281-1289.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mobley H L T, Jarvis K G, Elwood J P, Whittle D I, Lockatell C V, Russell R G, Johnson D E, Donnenberg M S, Warren J W. Isogenic P-fimbrial deletion mutants of pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli: the role of αGal(1-4) Gal binding in virulence of a wild-type strain. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:143–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norgren M, Baga M, Tennent J M, Normark S. Nucleotide sequence, regulation and functional analysis of the papC gene required for cell surface localization of Pap pili of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1987;1:169–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1987.tb00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Normark S, Lark D, Hull R. Genetics of digalactoside-binding adhesin from a uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect Immun. 1983;41:942–949. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.942-949.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Hanley P, Low D, Romero I, Lark D, Vosti K, Falkow S, Schoolnik G. Gal-gal binding and hemolysin phenotypes and genotypes associated with uropathogenic Escherichia coli. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:414–420. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198508153130704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhen M, van Die I, Rhen V, Bergmans H. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the genes encoding the KS71A and F71 fimbrial antigens of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1985;151:573–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritter A, Blum G, Emody L, Kerenyi M, Bock A, Neuhierl B, Rabsch W, Scheutz F, Hacker J. tRNA genes and pathogenicity islands: influence on virulence and metabolic properties of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:109–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandberg T, Kaijser B, Lidin-Janson G, Lincoln K, Ørskov F, Ørskov I, Stokland E, Svanborg-Edén C. Virulence of Escherichia coli in relation to host factors in women with symptomatic urinary tract infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1471–1476. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.8.1471-1476.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schnetz K, Rak B. Regulation of the bgl operon of Escherichia coli by transcriptional antitermination. EMBO J. 1988;7:3271–3277. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnetz K, Toloczyki C, Rak B. β-Glucoside (bgl) operon of Escherichia coli K-12: nucleotide sequence, genetic organization, and possible evolutionary relationship to regulatory components of two Bacillus subtilis genes. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2579–2590. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2579-2590.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swenson D L, Bukanov N O, Berg D E, Welch R A. Two pathogenicity islands in uropathogenic Escherichia coli J96: cosmid cloning and sample sequencing. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3736–3743. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3736-3743.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Die I, Bergmans H. Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the F72 fimbrial subunit of a uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Gene. 1984;32:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warren J W, Tenney J H, Hoopes H M, Muncie H L, Anthony W C. A prospective microbiologic study of bacteriuria in patients with chronic indwelling urethral catheters. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:719–723. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.6.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]