Abstract

Each of the exchange–correlation functionals in the density functional theory has been customized to particular systems or elements and has unique advantages and disadvantages. In one of the most recent research on exchange–correlation functionals, Chachiyo et al. present a relationship for exchange–correlation functional by assuming the simplest form of electron density. Their utilized electron density causes a systematic inaccuracy in the energy of the molecules since it does not fully account for the variation of the ionization energy for different atoms. We offer a novel relationship for exchange functional that improves the precision of the energy calculations for molecules by using the basic assumptions of the Chachiyo approach and correcting the electron density. Our density is directly related to the atom’s ionization energy. Our suggested functional was implemented for 56 molecules composed of atoms from the first, second, and third rows of the periodic table using Siam Quantum package. We discussed about the role of our functional on the reducing the computation error of dipole moment along with total, bonding and zero point energies. We also increased the portion of core electrons to improve the accuracy of the results.

Subject terms: Physical chemistry, Materials science, Physics

Introduction

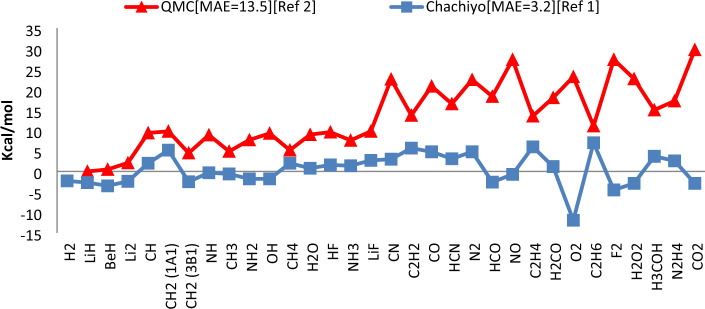

Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) is employed to obtain one of the most precise estimates for the total energy of atoms in the framework of many particle systems1. As shown in Fig. 1, the mean absolute error (MAE) of QMC for molecules made from the first row of the periodic table and other rows, respectively, is 13.5 and 23.7 kcal/mol. Since QMC computations are very time-consuming, other approaches are currently being developed. Density functional theory (DFT) is one of them. It uses the electron correlation, kinetic and exchange energies, nuclear-electron interaction, and classical electron–electron Coulomb repulsion to determine the energy of a system. Since the correlation term is not taken into consideration in Hartree–Fock (HF) theory, the exchange energy determined precisely in HF cannot be employed in DFT2. Exchange energy can be calculated using a variety of approaches. These approaches depend on the electron density (n) as well as its gradients. Determining an exact exchange functional specially in the intermediate region, where electron density decays outside molecules between slow and rapid variation limit, is still under discussion. The primary aim of this work is to obtain exchange energy values that lead to results that are more accurate than QMC in all regions.

Figure 1.

Total energy prediction error in terms of kilojoules/mol obtained from quantum Monte Carlo method and Chachiyo model for molecules containing atoms of the first and second rows of the periodic table1.

As predicted by the Thomas–Fermi model, the exchange energy enhancement in a system with slowly varying density is proportional to , where S is a function of the reduced density gradient and is equal to . According to the Kleinman model and taking into account an alternative external potential with a long wavelength as a perturbation, the coefficient has a constant value of 8/213. In order to achieve more precise results for the total energy, Chachiyo et al. added the Bragg scattering condition for Fermi electrons and obtained a greater value for 1. Then, using the assumption that the electron density decays exponentially as , they offered a novel relationship for the exchange energy that led to accurate results for the total energy, particularly for a system with intermediate varying density1. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the error value of Chachiyo model (CM) for computing the total energy of molecules is acceptable and better than QMC.

The work by Chachiyo et al. actually misses a key aspect because the ionization energy is different for various atoms and the same relation for electron density should not be used for all of them. In this work, we utilized the density of electrons as that clearly depends on the atom’s ionization4. We analytically derive a new relation for the exchange functional that is more accurate than previous attempts and works well in all slow, rapid, and intermediate varying density regions. To verify the accuracy of our results for different kinds of structures, we employed a set of reference data5.

Theoretical method

An interacting many-particle system is described by the DFT exclusively in terms of its density and the system energy is stated as6–8:

| 1 |

| 2 |

F and Vion, respectively, stand for universal function and external potential in Eq. (2). The charge density contains all the information related to the system’s ground state9.

| 3 |

And the density is calculated using the variational method as follows:

| 4 |

Equation (2) may also be rewritten as follows:

| 5 |

where is the exchange correlation (XC) energy, which is defined by the following relationship:

| 6 |

where represent exchange energy per electron. Gradient corrections are required in Eq. (6) to take into account the long-range gradient effects. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) is the model that accomplishes this as:

| 7 |

As mentioned earlier, the density in Eq. (7) is employed as follows in our model4:

| 8 |

where . For this density, is obtained as:

| 9 |

In Eq. (8), I stands for the ionization energy and A is a constant. Equations (8) and (9) result:

| 10 |

For a homogeneous electron gas, the Dirac exchange energy per electron, or , equals10:

| 11 |

The density determined by Eq. (8) yields the value of as follows:

| 12 |

Additionally, by using following equation for S10:

| 13 |

As the reduced gradient parameter in the primary Ex equation, the exchange energy will take the form:

| 14 |

Therefore, S can be expressed as follows using Eq. (10):

| 15 |

In the limit of ,

| 16 |

Now, using Eq. (12) and this equation for S, we can derive the following equation for :

| 17 |

At the asymptotic limit of , the exchange energy density should behave as10:

| 18 |

Since the value of the optimum coefficient should be equal to 1 at S = 0 limit, Fx(S) is expressed as follows:

| 19 |

The relationship between r and S can be identified through Eq. (16). Assuming:

| 20 |

And using W as the Lambert function, we obtain:

| 21 |

In this case, Fx(S) is resulted as:

| 22 |

Equation (22) is obtained in the asymptotic range S → ∞. A weight function is required to extend the application of this formula to the intermediate range between S → ∞ and S → 0 limits. should not diverge to infinity in the limit s → 0, thus we modify its functional as follows:

| 23 |

The weight function is then introduced as where d is a constant that controls the weight function's speed from the ranges between low variation range to the asymptotic limit. Since the value of the functional at S = 0 must be equal to 1, we rewrite the weight function as follows:

| 24 |

We derive the following series for the functional by using Taylor expansion up to the second order around the zero point:

| 25 |

which is comparable to the reported ( behavior for the low variation range3.

We obtain the following value for d in Eq. (25) by applying Chachiyo et al.’s suggested :

| 26 |

We ultimately achieved the non-experimental exchange functional in this work by using the value of d found in Eq. (26) and defining the new variable :

| 27 |

The exchange energy was calculated using this F(x) as follows:

| 28 |

We combined this exchange energy with the subsequent correlation energy to create a new exchange–correlation energy for DFT computations:

| 29 |

We examine the accuracy of the introduced exchange–correlation energy for the set of atoms and molecules using Siam Quantum software and calculating Lambert function (Appendix A)11,12.

Results and discussion

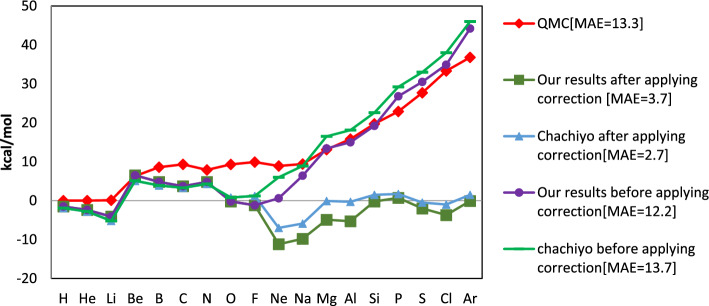

The suggested exchange energy and functional in Eqs. (28) and (29) offers a very accurate total energy for a set of the atoms and molecules in the first and second rows of the periodic table. Figure 2 illustrates the errors of the estimated total energies of single atoms. For atoms smaller than Ne, the fit performance is excellent; however, it is less precise for bigger atoms.

Figure 2.

The mean absolute errors of the estimated total energies of single atoms. For atoms smaller than Ne, the fit performance is excellent; however, it is less precise for bigger atoms.

A quick correction approach utilized to increase the accuracy of total energy1. This approach is predicated on taking into account how core electrons affect the quantity of energy. Exchange functional performs exceptionally well for atoms smaller than Ne, but it performs less accurately for larger atoms. A precise and straightforward adjustment for atoms and molecules can be applied to overcome this issue. For each core ion, such as the magnesium ion, we first compute the exchange energy error using the Hartree–Fock computations. Hartree–Fock orbitals are the results of this. Next, we compute the DFT exchange energy (28) using density equation and the Hartree–Fock exchange energy utilizing these orbitals. As shown in Fig. 2, the errors were decreased after applying the correction. The MAE of the entire set of 56 molecules was only 3.7 kcal/mol. (ExDFT–EHF) for core electrons are nearly identical to the errors of the predicted total energies, as Fig. 3 illustrates. We take into account the 1S2 orbital as the core electrons from the H atom to the Al atom in our error correction technique, and the 2S22P6 orbitals for the atoms larger than the Al atom (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(Ex-DFT-EHF) core correction and the error of total energy for neutral atoms.

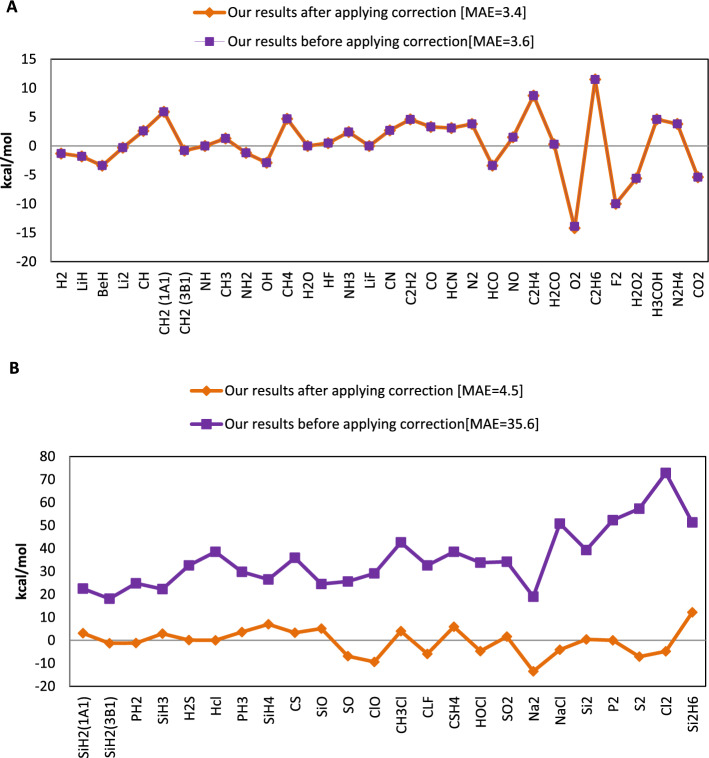

In Fig. 4, this correction method depicted for molecules containing atoms from the first, second, and third rows of the periodic table.

Figure 4.

(Ex-DFT-EHF) core correction and the error of total energy for molecules including (A) first and second row atoms and (B) third row atoms.

For molecules containing atoms from the third row, this method very precisely illustrates the equality of the core electrons with the errors of predicted total energies.

The mean error (ME) of the total energy for the molecules containing the first, the second and the third rows of periodic table atoms is compared in Fig. 5. As shown in the caption of Fig. 5, the absolute mean error (MAE) for the first and second row molecules is better than the third row. These values for MAE are four times more accurate than the QMC result.

Figure 5.

The errors of total energy obtained using our exchange functional in comparison to the experimental data for the total energy (kcal/mol) of molecules that (A) contain atoms from the first and second rows of the periodic table and (B) contain atoms from the third row of the periodic table.

Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of the total energy produced by our developed XC functional as well as reference energies of atoms and molecules for computing the error value13.

Table 1.

The total energy of examined atoms (versus Hartree)13.

| Atoms | Total energy (experimental) | Total energy (our model) |

|---|---|---|

| H | − 0.5000 | − 0.502554 |

| He | − 2.9037 | − 2.907579 |

| Li | − 7.4781 | − 7.484782 |

| Be | − 14.6674 | − 14.65707 |

| B | − 24.6539 | − 24.64627 |

| C | − 37.845 | − 37.83908 |

| N | − 54.5892 | − 54.58151 |

| O | − 75.0673 | − 75.06775 |

| F | − 99.7339 | − 99.73586 |

| Ne | − 128.9376 | − 128.95558 |

| Na | − 162.2546 | − 162.27037 |

| Mg | − 200.053 | − 200.06092 |

| Al | − 242.346 | − 242.35457 |

| Si | − 289.359 | − 289.35931 |

| P | − 341.259 | − 341.25789 |

| S | − 398.11 | − 398.10728 |

| Cl | − 460.148 | − 460.15389 |

| Ar | − 527.54 | − 527.54032 |

Table 2.

The total energy of examined molecules (versus Hartree)13.

| Molecules | Total energy (experimental) | Total energy (our model) |

|---|---|---|

| Li2 | − 14.9951 | − 14.99553 |

| CH | − 38.4788 | − 38.47462 |

| CH2 (1A1) | − 39.1346 | − 39.12451 |

| CH2 (3B1) | − 39.1484 | − 39.14978 |

| NH | − 55.2227 | − 55.22271 |

| CH3 | − 39.8355 | − 39.83338 |

| NH2 | − 55.8794 | − 55.88145 |

| OH | − 75.7371 | − 75.74185 |

| CH4 | − 40.5158 | − 40.50829 |

| H2O | − 76.4383 | − 76.43823 |

| HF | − 100.459 | − 100.4600 |

| H2 | − 1.1745 | − 1.176598 |

| LiH | − 8.0704 | − 8.073238 |

| CO | − 113.326 | − 113.3207 |

| HCN | − 93.4311 | − 93.42615 |

| N2 | − 109.542 | − 109.5360 |

| HCO | − 113.857 | − 113.8624 |

| NO | − 129.905 | − 129.9022 |

| C2H4 | − 78.5888 | − 78.57484 |

| H2CO | − 114.509 | − 114.5084 |

| O2 | − 150.327 | − 150.3493 |

| C2H6 | − 79.8274 | − 79.80910 |

| F2 | − 199.53 | − 199.5463 |

| H2O2 | − 151.564 | − 151.5724 |

| H3COH | − 115.731 | − 115.7231 |

| N2H4 | − 111.878 | − 111.8715 |

| CO2 | − 188.601 | − 188.6098 |

| BeH | − 15.2468 | − 15.25018 |

| SiH2(3B1) | − 290.569 | − 290.5712 |

| H2S | − 399.403 | − 399.4023 |

| Hcl | − 460.819 | − 460.8197 |

| PH3 | − 343.146 | − 343.1403 |

| SiH4 | − 291.874 | − 291.8631 |

| CS | − 436.229 | − 436.2236 |

| SiO | − 364.734 | − 364.7255 |

| SO | − 473.378 | − 473.3893 |

| ClO | − 535.32 | − 535.3352 |

| CH3Cl | − 500.124 | − 500.1178 |

| CLF | − 559.982 | − 559.9915 |

| CSH4 | − 438.712 | − 438.7029 |

| HOCl | − 535.98 | − 535.9870 |

| SO2 | − 548.659 | − 548.6561 |

| Na2 | − 324.536 | − 324.5576 |

| LiF | − 107.434 | − 107.4343 |

| SiH2 (1A1) | − 290.602 | − 290.5969 |

| Cl2 | − 920.39 | − 920.3977 |

| Si2H6 | − 582.567 | − 582.5472 |

| NaCl | − 622.561 | − 622.5670 |

| Si2 | − 578.839 | − 578.8378 |

| P2 | − 682.704 | − 682.7042 |

| S2 | − 796.384 | − 796.3956 |

| PH2 | − 342.504 | − 342.5055 |

| SiH3 | − 291.221 | − 291.2170 |

| CN | − 92.725 | − 92.72058 |

| C2H2 | − 77.3355 | − 77.32817 |

| NH3 | − 56.5647 | − 56.56075 |

The ME and MAE for neutral atoms obtained with our functional are less than CM, as Table 3 illustrates. Our exchange functional’s ME is nearly zero for the total energy of the 56 molecules after rapplying correction, making it more accurate than the CM’s reported 1 kcal/mol value, even though it yielded a 3.9 kcal/mol MAE, which is higher than the CM’s reported 3.5 kcal/mol value. Table 4 illustrates the errors of the total energy for our model and the CM.

Table 3.

The comparison of the our and Chachiyo models total energy errors for neutral atoms.

| Total energy | Chachiyo model | Chachiyo model with correction | Our model | Our model with correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME (for all neutral atoms) | 12.6 | − 0.1 | 11.2 | − 1.4 |

| MAE (for all neutral atoms) | 13.7 | 2.7 | 12.2 | 3.7 |

| ME (for first and second row neutral atoms) | 1.5 | 0.2 | 1.1 | − 0.1 |

| MAE (for first and second row neutral atoms) | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 |

The unit of every energy is kcal/mol.1.

Table 4.

The comparison of the our and Chachiyo models total energy errors for examined 56 molecules.

| Total energy | Chachiyo model | Chachiyo model with correction | Our model | Our model with correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME (for 56 molecules) | 16.9 | 1.0 | 15.5 | 0.0 |

| MAE (for 56 molecules) | 18.5 | 3.5 | 17.3 | 3.9 |

| ME (for molecules made up from first and second row atoms) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| MAE (for molecules made up from first and second row atoms) | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

The unit of every energy is kcal/mol.1.

Additionally, we compared our total energy’s ME with the results of the well-known B3LYP, BLYP, PBE, OLYP, QMC, and CE methods1,14–16. The ME for the reference energies and for the molecules of the first and second rows of the periodic table is approximately 0.4 kcal/mol and which is same as our functional result as illustrated in Fig. 612. Our functional estimates 17.3 kcal/mol MAE for the total energy without applying any corrections. For the CM, this error was equal to 18.5 kcal/mol.

Figure 6.

The total energy mean absolute error (kcal/mol) of various DFT approaches compared to the experimental values for molecules that contain (A) atoms from the first and second rows of the periodic table and (B) atoms from the third row of the periodic table.

Although the errors are only a few kcal/mol for molecules made up of atoms from the first and second rows of the periodic table, they drastically increase for molecules composed of toms from the third row. This increase in errors is caused by the core electrons.

Additionally, we used both corrected and uncorrected energies to evaluate molecules bond energy (Eb) using1:

| 30 |

where E(A) and E(M) represent the total energies of atoms and molecules, respectively. In Fig. 7, the bond energy errors are displayed. MAE for molecules having atoms from the first and second rows of periodic table, from the third row of periodic table, and for all 58 molecules is equal to 4.6, 5.7 and 5.1, respectively. The MAE value for all molecules is decreased to 0.0 kcal/mol considering the core correction in Eq. (30). In this case, the atomic energies from reference13, along with the corrected molecule energy are employed.

Figure 7.

The bond energies mean absolute error (kcal/mol) obtained by our new functional compared to the experimental value for (A) molecules containing atoms of the first and second rows of the periodic table and (B) molecules containing atoms of the third row of the periodic table.

In Fig. 8, the MAE for our bond energy is compared with the QMC and CM approaches.

Figure 8.

The bond energies mean absolute error (kcal/mol) obtained by various models compared to the experimental values for (A) molecules containing atoms of the first and second rows of the periodic table and (B) molecules containing atoms of the third row of the periodic table.

Table 5 compares the bond energy errors for our model and the CM.

Table 5.

The comparison of the bond energy errors for our and Chachiyo models.

| Bond energy error | Chachiyo model | Chachiyo model with correction | Our model | Our model with correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME (for 56 molecules) | − 1.9 | − 1.0 | − 1.9 | 3.9 |

| MAE (for 56 molecules) | 4.7 | 3.5 | 5.1 | 0.0 |

| ME (for molecules made up from first and second row atoms) | − 0.3 | − 0.4 | 0.0 | − 0.4 |

| MAE (for molecules made up from first and second row atoms) | 4.4 | 3.2 | 4.6 | 3.4 |

The unit of every energy is kcal/mol.

Dipole moments are also analyzed using our employed electron density at this work. Our results and experimental data for dipole moments are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

The experimental and our results for zero point energy and dipole moment of molecules.

| Molecules | EZP | Dipole moments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Our calc (kc/mol) | ME | Experimental | Our calc (Debye) | ME | |

| H2 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| LiH | 2.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 5.87 | 5.74 | − 0.13 |

| BeH | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.0 |

| Li2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| CH | 4.0 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 1.45 | 1.42 | − 0.03 |

| NH | 4.6 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 1.39 | 1.49 | 0.1 |

| NH2 | 11.5 | 12.0 | 0.5 | 1.76 | 1.76 | 0.0 |

| OH | 5.3 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 1.65 | 1.62 | − 0.03 |

| CH4 | 27.1 | 27.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| H2O | 12.9 | 13.1 | 0.2 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 0.0 |

| HF | 5.9 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 1.82 | 1.77 | − 0.05 |

| NH3 | 20.6 | 21.0 | 0.4 | 1.47 | 1.50 | 0.03 |

| LiF | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 6.31 | 6.13 | − 0.18 |

| CN | 2.9 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 0.0 |

| C2H2 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| CO | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.08 |

| HCN | 8.7 | 9.0 | 0.3 | 2.98 | 2.90 | − 0.08 |

| N2 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| HCO | 7.8 | 7.9 | 0.1 | 1.39 | 1.39 | 0.0 |

| NO | 2.7 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| H2CO | 16.1 | 16.1 | 0.0 | 2.32 | 2.19 | − 0.13 |

| O2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| F2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| H2O2 | − | 16.3 | − | 1.57 | 1.72 | 0.15 |

| CH4O | − | 31.7 | − | 1.69 | 1.56 | − 0.13 |

| N2H4 | − | 32.6 | − | 1.75 | 1.87 | 0.12 |

| CO2 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| SiH2 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 0.2 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.0 |

| H2S | 9.2 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 0.07 |

| HCl | 4.2 | 4.3 | 0.1 | 1.11 | 1.13 | 0.02 |

| PH3 | 14.6 | 14.7 | 0.1 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.13 |

| SiH4 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| CS | 1.8 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 1.95 | 1.93 | − 0.02 |

| SiO | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 3.09 | 2.83 | − 0.26 |

| SO | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.54 | 1.36 | − 0.18 |

| ClO | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 1.38 | 0.08 |

| CH3Cl | − | 23.3 | − | 1.88 | 1.87 | − 0.01 |

| ClF | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.88 | 0.75 | − 0.13 |

| CSH4 | − | 28.5 | − | 1.52 | 1.56 | 0.04 |

| HOCl | 8.0 | 8.1 | 0.1 | 1.40 | 1.53 | 0.13 |

| SO2 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 1.62 | 1.48 | − 0.14 |

| Na2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| NaCl | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 8.99 | 8.8 | − 0.19 |

| Si2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| P2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| S2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cl2 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| MAE | 0.11 | MAE | 0.09 | |||

| ME | 0.11 | ME | − 0.02 | |||

The units are in Debye5.

As summarized in Table 7, MAE is obtained 0.09 Debye which is comparable to the DFT-based estimations and better than CM17.

Table 7.

The comparison of the dipole moment errors for our and Chachiyo models.

| Dipole moment | Chachiyo model | Chachiyo model with correction | Our model | Our model with correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | − 0.03 | − 0.02 | ||

| MAE | 0.11 | 0.09 |

The unit of every energy is kcal/mol.1.

In contrast to classical mechanics, quantum systems fluctuate around zero-point energy (EZP) even at absolute zero temperature. In order to calculate vibration frequencies, the accuracy of EZP should be increased. EZP can be calculated using Eq. (31) as18:

| 31 |

where i represent the frequency of a certain molecule and h is the Planck constant. Table 8 provides an overview of our findings and the experimental data for EZP.

Table 8.

The comparison of the zero point energy errors for our and Chachiyo models.

| Zero point energy | Chachiyo model | Chachiyo model with correction | Our model | Our model with correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | − 0.005 | 0.11 | ||

| MAE | 0.12 | 0.11 |

The unit of every energy is kcal/mol.1.

The MAE of the EZP, as shown in Table 8, is 0.11 kcal/mol, which is comparable to the Chachiyo prediction1. In this investigation, the QZP-g basis set was employed.

We compared the errors of zero point energy for our and CM in Table 8.

As a result, in addition to the total energies, our exchange correlation can also reliably predict the dipole moment, EB and EZP.

We were curious to see how our exchange functional performed with various organic and solid substances. We also achieved satisfactory results for their dipole moment, zero-point energy, and total energy, as Table 9 shows.

Table 9.

Comparison of three organic and six solid materials’ zero point energy (EZP), dipole moment, and total energy19–23.

| Molecules | EZP (kcal/mol) | Experimental EZP (kcal/mol) | EZP error | Dipole moment (Debye) | Experimental dipole moment | Dipole moment error | Total energy (Hartree) | Experimental total energy (Hartree) | Total energy error (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiadiazole (1-3-4 C2H2N2S) | 26.80 | 27.4 [22] | 0.6 | 2.76 | 1.57 [23] | 1.19 | − 584.99 | − 584.92 [22] | − 43.8 |

| Thiophene (C4H4S) | 43.90 | 43.6 [22] | 0.3 | 0.71 | 0.55 [19, 20] | 0.16 | − 552.92 | − 552.95 [22] | − 20.33 |

| Benzothiazole (C7H5NS) | 65.34 | − | − | 1.39 | 1.46 [19, 20] | 0.07 | − 714.05 | − | − |

| BeO | 2.05 | 2.05 [22] | 0.0 | 5.31 | − | − | − 89.849 | − 89.846 [22] | 1.96 |

Dashed line shows that experimental value is not available.

Siam-Quantum can be used to compute additional variables, such as molecular vibrations and the related normal modes and forces, which were computed for solids. Table 10 presents an overview of the results achieved for these parameters.

Table 10.

Molecular vibration properties of some solid materials’.

| Material | Atoms | Vibration wave number (Cm–1) | Normal mode vibration | Forces (Hartrees/Bohr) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fx | Fy | Fz | ||||||

| BeO | Be | 1440.6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.2669 | 0.00000 | − 0.00000 | − 0.002106 |

| O | − 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.1496 | − 0.00000 | 0.000000 | 0.004986 | ||

| LiSi | Li | 379.0 | 0.0684 | − 0.0667 | − 0.3230 | 0.00009 | − 0.000138 | − 0.000331 |

| Si | − 0.0171 | 0.0165 | 0.0819 | − 0.00006 | 0.000212 | 0.000075 | ||

| Na2S | Na | 301.7 | 0.0658 | 0.0659 | 0.0661 | 0.000585 | 0.000584 | 0.000577 |

| S | − 0.0919 | − 0.0919 | − 0.0920 | 0.000099 | 0.000099 | 0.000099 | ||

| BeCl2 | Be | 844.5 | 0.0414 | 0.0414 | − 0.0492 | 0.005446 | 0.005452 | − 0.006449 |

| Cl | − 0.1606 | − 0.1609 | 0.1913 | − 0.003795 | − 0.003800 | 0.004498 | ||

| MgF2 | Mg | 709.3 | − 0.1209 | − 0.1209 | 0.0000 | 0.002517 | 0.002517 | 0.000007 |

| F | 0.0963 | 0.0963 | − 0.0000 | 0.000928 | 0.000928 | 0.000007 | ||

| MgB2 | Mg | 351.1 | 0.0000 | 0.0812 | 0.0803 | − 0.00000 | 0.000065 | 0.000068 |

| B | 0.0000 | − 0.1776 | − 0.1757 | 0.000000 | 0.000617 | 0.000609 | ||

| LiH | Li | 333.5 | 0.0358 | 0.0716 | − 0.1074 | 0.014346 | 0.014346 | 0.014316 |

| H | − 0.2490 | − 0.4978 | 0.7467 | − 0.014342 | − 0.014342 | − 0.014312 | ||

| BeH | Be | 2270.6 | 0.0000 | − 0.0000 | 0.1056 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | − 0.004285 |

| H | 0.0000 | − 0.0000 | − 0.9447 | − 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.004291 | ||

| Li2 | Li | 391.1 | − 0.0000 | 0.0000 | − 0.2670 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.002038 |

| Li | − 0.0000 | − 0.0000 | − 0.2670 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | − 0.002038 | ||

| LiF | LI | 845 | 0.0000 | − 0.0000 | − 0.3229 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | − 0.030607 |

| F | − 0.0000 | − 0.0000 | 0.1189 | − 0.000000 | − 0.000000 | 0.031051 | ||

| Na2 | Na | 144.6 | 0.0258 | − 0.1452 | − 0.0000 | − 0.000000 | − 0.000000 | 0.054220 |

| Na | − 0.0258 | 0.1452 | 0.0000 | 0.000000 | − 0.000000 | − 0.054220 | ||

| NaCl | Na | 410.7 | 0.0000 | − 0.0000 | 0.1621 | − 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.026416 |

| Cl | − 0.0000 | 0.0000 | − 0.1064 | 0.000000 | − 0.00000 | − 0.026457 | ||

| SiO | Si | 1370.4 | 0.0000 | − 0.0000 | 0.1140 | − 0.00000 | − 0.00000 | 0.049936 |

| O | − 0.000 | 0.0000 | − 0.1994 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | − 0.049961 | ||

Conclusion

In this paper, we derive an accurate and straightforward exchange functional that can be applied in the intermediate, slow and fast density variation limits. According to calculations on first, second and third rows of periodic table neutral atoms and 56 molecules, our exchange functional accurately predicts the total energy, dipole moment, bond and zero point energies. The total energy mean error of our functional is 0.0 for examined 56 molecules which shows that it concludes more accurate results than other exchange functionals. The mean absolute error of the total energy for the mentioned molecules are calculated was obtained 3.9 kcal/mol which is higher than the result of CM calculations but is better than the QMC result. The error of our functional for the third row of the periodic table's atoms was greater than that of the first and second rows’ atoms because of the role of core atoms. Our functional results for neutral atoms are comparable to CM as evidenced by its low ME and MAE. The MAE for the estimated zero-point energy and dipole moments also confirms the accuracy of our new exchange functional.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

A.E. wrote the main manuscript text and E.R. prepared all figures and Tables. All authors participated on the introducing of the new functional model and reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. If required, any data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-53341-4.

References

- 1.Chachiyo T, Chachiyo H. Simple and accurate exchange energy for density functional theory. Molecules. 2020;25(15):3485. doi: 10.3390/molecules25153485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sholl DS, Steckel JA. Density Functional Theory: A Practical Introduction. Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinman L. Exchange density-functional gradient expansion. Phys. Rev. B. 1984;30(4):2223–2225. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.30.2223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katriel J, Davidson ER. Asymptotic behavior of atomic and molecular wave functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1980;77(8):4403–4406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lide DR. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 85. Taylor & Francis; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabo A, Ostlund NS. Modern Quantum Chemistry: Introduction to Advanced Electronic Structure Theory. Courier Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartlett RJ, Purvis GD. Many-body perturbation theory, coupled-pair many-electron theory, and the importance of quadruple excitations for the correlation problem. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1978;14(5):561–581. doi: 10.1002/qua.560140504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Needs RJ, Towler MD, Drummond ND, López RP. Continuum variational and diffusion quantum Monte Carlo calculations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2010;22(2):023201. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/2/023201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernzerhof M, Scuseria GE. Perspective on “Inhomogeneous electron gas”. In: Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG, editors. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts: New Century Issue. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2001. pp. 259–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.March NH. Asymptotic formula far from nucleus for exchange energy density in Hartree-Fock theory of closed-shell atoms. Phys. Rev. A. 1987;36(10):5077–5078. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.36.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veberič D. Lambert W function for applications in physics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2012;183(12):2622–2628. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2012.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chachiyo, T. A compact open-source quantum simulation software for molecules. Siam Quantum (2020).

- 13.O’Neill DP, Gill PMW. Benchmark correlation energies for small molecules. Mol. Phys. 2005;103:763–766. doi: 10.1080/00268970512331339323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98(7):5648–52. doi: 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37(2):785–789. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill PMW, Johnson BG, Pople JA, Frisch MJ. The performance of the Becke—Lee—Yang—Parr (B—LYP) density functional theory with various basis sets. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992;197(4):499–505. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(92)85807-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dale SG, Johnson ER, Becke AD. Interrogating the Becke’05 density functional for non-locality information. J. Chem. Phys. 2017 doi: 10.1063/1.5000909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahal M, Hilali M, El Hammadi A, El Mouhtadi M, El Hajbi A. Calculation of vibrational zero-point energy. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 2001;572(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/S0166-1280(01)00565-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adhikari S, Santra B, Ruan S, Bhattarai P, Nepal NK, Jackson KA, Ruzsinszky A. The Fermi-Löwdin self-interaction correction for ionization energies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2020 doi: 10.1063/5.0024776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClellan AL. Tables of Experimental Dipole Moments. Freeman, American Association for the Advancement of Science; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch BJ, Truhlar DG. Small representative benchmarks for thermochemical calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107(42):8996–8999. doi: 10.1021/jp035287b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell D. Johnson III .NIST computational chemistry comparison and benchmark database.NIST standard reference database number 101. http://cccbdb.nist.gov (Accessed 22 May 2022).

- 23.Dobyns V, Pierce L. Microwave spectrum, structure, dipole moment, and quadrupole coupling constants of 1,2,5-thiadiazole. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85(22):3553–3556. doi: 10.1021/ja00905a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. If required, any data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.